Enhancing Eukaryotic Promoter Amplification: A Guide to PCR Enhancers for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to successfully amplify eukaryotic promoter regions, a task often hampered by high GC content, complex secondary structures,...

Enhancing Eukaryotic Promoter Amplification: A Guide to PCR Enhancers for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to successfully amplify eukaryotic promoter regions, a task often hampered by high GC content, complex secondary structures, and inhibitory substances. We explore the foundational challenges of promoter architecture and the mechanistic role of PCR enhancers like DMSO, betaine, and formamide. The content delivers robust methodological protocols, advanced troubleshooting strategies, and a comparative analysis of validation techniques to ensure specific, efficient, and high-fidelity amplification for downstream applications in gene regulation studies, therapeutic development, and functional genomics.

Understanding the Challenge: Why Eukaryotic Promoters Are Difficult to Amplify

Structural Complexity of Eukaryotic Promoters and Regulatory Regions

Eukaryotic promoters are specialized DNA sequences at transcription start sites (TSSs) of protein-coding and non-coding genes that support the assembly of the transcription machinery and initiation of transcription. These regulatory regions, typically spanning approximately 100 base pairs around the TSS, serve as platforms for receiving and integrating regulatory cues from distal enhancers and associated regulatory proteins [1]. The development of complex organisms with morphologically and functionally diverse cell types is largely determined by genetic information contained within genomic DNA, with regulated gene expression being essential for cellular integrity, differentiation, metabolism, and disease prevention [1].

Eukaryotic promoters exhibit tremendous structural and functional diversity, which defines distinct transcription programs. The core promoter works in conjunction with proximal promoters (approximately 500 base pairs upstream of TSS) and distal regulatory elements including enhancers, insulators, and silencers to precisely control gene expression [2]. Understanding this complex architecture is crucial for advancing research in gene regulation, synthetic biology, and therapeutic development, particularly in the context of amplifying eukaryotic promoter regions with PCR enhancers.

Structural and Functional Diversity of Eukaryotic Promoters

Core Promoter Types and Characteristics

Eukaryotic core promoters display remarkable diversity in their sequence composition, chromatin architecture, and transcription initiation patterns. Based on comprehensive mapping of endogenous transcription initiation sites, promoters can be classified into distinct types with characteristic properties [1]:

Table 1: Classification of Eukaryotic Core Promoter Types

| Promoter Type | Initiation Pattern | Sequence Features | Chromatin Configuration | Associated Gene Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focused/Sharp | Single, well-defined TSS | TATA-box, Initiator (Inr) | Imprecisely positioned nucleosomes | Highly cell-type specific genes |

| Dispersed/Broad | Multiple closely-spaced TSSs | CpG islands (mammals), Ohler motifs (flies) | Well-defined nucleosome-depleted region (NDR) flanked by positioned nucleosomes | Housekeeping genes |

| Poised/Developmental | Varies (focused in flies, broad in mammals) | Downstream promoter element (DPE) in flies, CpG islands in mammals | Bivalent chromatin marks (H3K4me3 + H3K27me3) | Developmental transcription factors |

The transcription initiation pattern represents a fundamental dichotomy in promoter structure. Focused promoters contain a single, well-defined transcription start site and are typically associated with tightly regulated genes with cell-type specific expression patterns. In contrast, dispersed promoters contain multiple closely-spaced transcription start sites used with similar frequency and are primarily associated with housekeeping genes expressed in many cell types [1]. In mammals, dispersed promoters often overlap with CpG islands, while in flies they are enriched for specific motifs including Ohler1, Ohler6, and DNA replication-related element (DRE) [1].

DNA Structural Properties and Promoter Prediction

Beyond specific sequence motifs, DNA structural properties provide universal features for promoter identification across diverse eukaryotic species. DNA duplex stability, expressed in terms of short-range nearest-neighbor interactions, represents a particularly informative structural feature that distinguishes promoter regions from other genomic sequences [2].

The PromPredict algorithm utilizes dinucleotide free energy information obtained from studies of oligonucleotide melting temperatures to compute average free energy as an indicator of DNA duplex stability. The fundamental premise is that promoter regions should be less stable than flanking regions to facilitate DNA melting during transcription initiation [2].

Research across 48 eukaryotic genomes has revealed that promoter regions consistently display characteristic free energy profiles:

Table 2: DNA Duplex Stability Profiles in Eukaryotic Promoters

| Organism Category | GC Content Characteristics | Stability Profile | Peak Locations Relative to TSS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast | AT-rich core promoters | Single narrow low stability region | -19 (S. cerevisiae) |

| Invertebrates (C. elegans, D. melanogaster) | AT-rich core promoters | Single narrow low stability region | -11 (C. elegans), -114 with split peak at -25 (D. melanogaster) |

| Vertebrates (zebrafish, mouse, human) | GC-rich core promoters | Two narrow low stability peaks | -27 and +2 (zebrafish), -29 and +6 (mouse), -30 and +1 (human) |

These structural signatures are conserved among closely related eukaryotes and provide a powerful approach for promoter prediction that complements sequence-based methods. The consistent presence of low stability regions in promoters, regardless of their GC content, highlights the importance of DNA structural properties in transcription initiation mechanisms [2].

Experimental Protocols for Promoter Analysis

Computational Identification of Putative Promoters

Protocol 1: Promoter Prediction Using DNA Duplex Stability

Principle: This protocol utilizes the PromPredict algorithm to identify putative promoter regions based on their characteristic DNA duplex stability profiles, which is applicable across diverse eukaryotic species regardless of their GC content [2].

Materials:

- Genomic sequence data in FASTA format

- PromPredict software (available as in-house implementation or from published sources)

- Computing environment with sufficient memory for genome-scale analysis

- Reference TSS or TLS data for validation (optional)

Methodology:

Sequence Preparation:

- Extract genomic sequences of interest from database or sequencing projects

- Format sequences in standard FASTA format

- For whole-genome analysis, segment into overlapping windows for scanning

Parameter Configuration:

- Set sliding window size to 100-150 base pairs

- Define step size of 10-50 base pairs depending on required resolution

- Establish GC-dependent energy thresholds based on organism characteristics

Free Energy Calculation:

- Compute average free energy using nearest-neighbor parameters

- Slide window across sequence with defined step size

- Record free energy values for each window position

Promoter Region Identification:

- Identify regions with significantly lower stability compared to flanking sequences

- Apply GC-adjusted threshold values to distinguish promoters

- Filter predictions based on proximity to annotated gene starts

Validation and Assessment:

- Compare predictions with experimentally validated TSS data

- Calculate recall rates (typically 68-92% across eukaryotes)

- Assess false positive rates in non-promoter regions

Troubleshooting:

- For GC-rich genomes (e.g., mammals), adjust thresholds to account for generally higher stability

- For genomes with atypical base composition, validate with known promoter sets

- Optimize window size for specific applications: smaller windows for precise TSS mapping, larger windows for regional characterization

Universal System for Boosting Gene Expression

Protocol 2: Enhancement of Promoter Activity Using Synthetic Upstream Regulatory Sequences (sURS)

Principle: This protocol describes the design and implementation of synthetic upstream regulatory regions (sURS) to boost expression from minimal core promoters in eukaryotic cell lines, based on recent research demonstrating universal functionality across yeast and mammalian systems [3].

Materials:

- Minimal core promoter (e.g., mCore1 for yeast systems)

- Library of 41 evolutionarily conserved regulatory motifs

- Plasmid backbone with reporter gene (e.g., yeCitrine)

- Eukaryotic host cells (S. cerevisiae, CHO-K1, HeLa)

- Molecular biology reagents for cloning and transformation

- Flow cytometry equipment for fluorescence quantification

- Next-generation sequencing platform for library analysis

Methodology:

sURS Design and Library Construction:

- Select motifs from the conserved set of 41 regulatory motifs

- Design variants containing 0, 1, 2, or 3 motifs in different arrangements

- Incorporate mixed bases (K = G/T, M = A/C) at variable positions to approximate position-weighted matrices

- Maintain 17 bp spacing between motifs within a synthetic "desert" chassis excluding endogenous TFBS

- Synthesize oligo library containing 189,990 variants with multiple barcodes

Library Cloning and Validation:

- Amplify library using PCR with appropriate primers

- Clone into plasmid vector upstream of minimal core promoter driving reporter expression

- Transform into E. cloni 10G electrocompetent cells for amplification

- Sequence intermediate library to assess coverage and diversity

Host Cell Integration and Expression Analysis:

- Linearize plasmids for genomic integration

- Integrate into defined genomic locus (e.g., URA3 in yeast)

- Culture cells in selective media for 3 days to ensure stable integration

- Analyze reporter expression using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

- Sort cells into 4 bins based on fluorescence intensity

Sequence-Function Modeling:

- Extract genomic DNA from each sorted population

- Amplify and barcode sURS regions for each bin

- Sequence using next-generation sequencing (Illumina platform)

- Analyze ~400 million valid reads to associate sURS sequences with expression levels

- Build machine learning model to predict boosting based on motif composition

Key Findings:

- Specific motif combinations function as "boosting" elements across eukaryotic species

- A generic regulatory grammar exists for expression enhancement

- The system functions similarly in yeast, CHO-K1, and HeLa cell lines

- Expression can be boosted significantly above baseline core promoter activity

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Eukaryotic Promoter Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Promoters | mCore1 (yeast), minimal CMV, minimal synthetic promoters | Provides basal transcription machinery binding platform | Minimal promoters enable clear detection of regulatory effects |

| Reporter Systems | yeCitrine, GFP, luciferase, secreted alkaline phosphatase | Quantification of promoter activity through measurable outputs | Fluorescent proteins enable FACS-based analysis and sorting |

| Computational Tools | PromPredict, Primer3, Biopython, custom ML algorithms | Prediction of promoter regions, primer design, sequence analysis | Biopython Seq objects facilitate sequence manipulation and analysis |

| Cloning Systems | Plasmid vectors, Gibson assembly, Golden Gate, restriction enzyme-based | Construction of reporter constructs and variant libraries | Modular systems enable rapid testing of regulatory combinations |

| Host Cell Lines | S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris, CHO-K1, HeLa, HEK293 | Eukaryotic expression environments with different regulatory landscapes | Choice affects post-translational modifications and expression levels |

| Sequence Libraries | sURS oligo library (189,990 variants), motif sets (41 conserved motifs) | High-throughput testing of regulatory sequences | Mixed-base synthesis approximates PWM complexity efficiently |

| Analysis Platforms | Next-generation sequencers, FACS, HPLC, mass spectrometry | Quantification of expression outcomes at transcript and protein levels | Multi-platform validation strengthens conclusions |

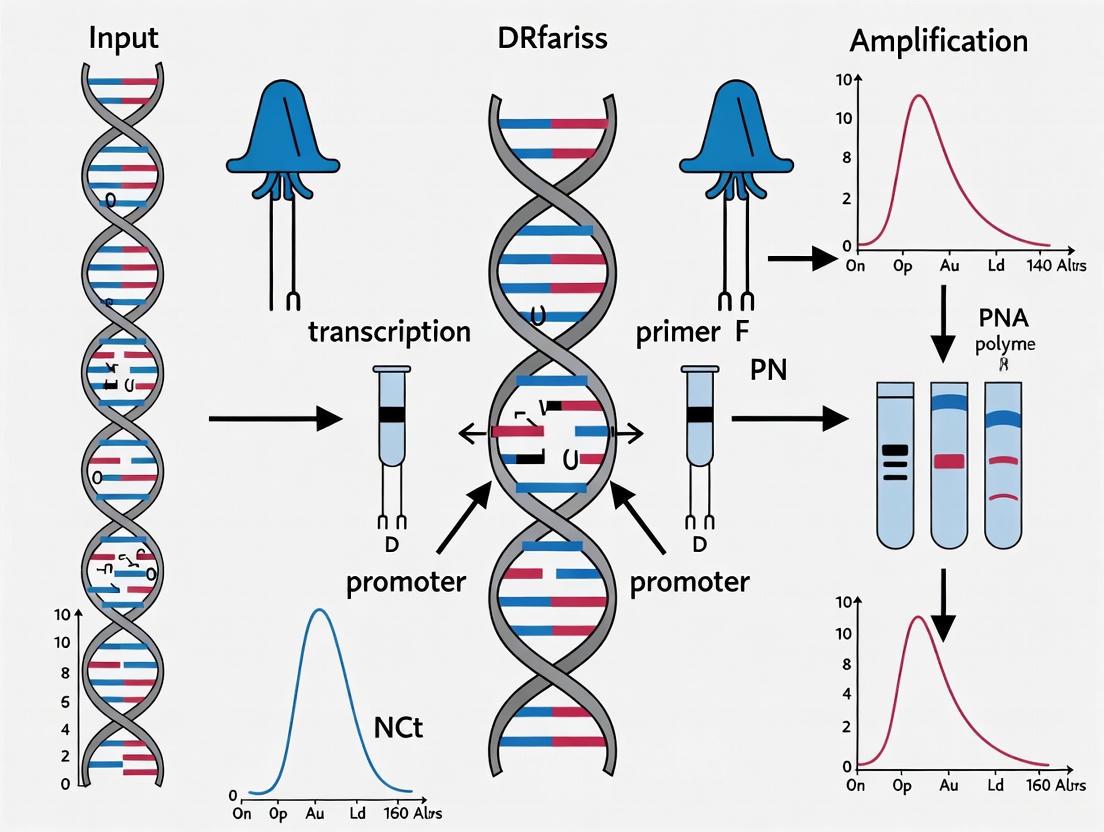

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

sURS Library Construction and Screening

PromPredict Algorithm Implementation

Applications in PCR Enhancement Research

The structural features of eukaryotic promoters have significant implications for PCR-based research and applications. Understanding promoter architecture enables the design of more effective PCR enhancers that can overcome amplification challenges associated with complex genomic regions.

GC-rich promoter amplification: Vertebrate promoters frequently occur in GC-rich regions that form stable secondary structures, impeding efficient PCR amplification. Knowledge of DNA duplex stability profiles guides the selection of PCR additives (such as DMSO, betaine, or glycerol) that destabilize these structures and improve amplification efficiency [2]. The characteristic low stability regions in otherwise GC-rich promoters represent optimal targets for primer design in promoter studies.

Regulatory element mapping: The ability to predict promoter regions based on structural properties enables targeted amplification of regulatory regions for functional analysis. Experimental design principles, including fractional factorial and central composite designs, can be applied to optimize PCR conditions for amplifying promoter regions with varying structural characteristics [4].

Universal boosting systems: The development of synthetic upstream regulatory sequences (sURS) that enhance expression across eukaryotic species provides novel approaches for expression optimization in biotechnology and therapeutic protein production. The identification of conserved boosting motifs enables design of regulatory cassettes that can be amplified and inserted upstream of genes of interest to significantly increase expression levels [3].

The integration of structural bioinformatics with experimental molecular biology approaches creates powerful synergies for advancing eukaryotic promoter research and its applications in gene expression control, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development.

The amplification of eukaryotic promoter regions is a fundamental prerequisite for research in transcriptional regulation, synthetic biology, and drug development targeting gene expression. These regions are notoriously difficult to manipulate using standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques due to their characteristically high guanine-cytosine (GC) content—often exceeding 60-70% and sometimes reaching 88%, as noted for the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promoter [5]. The inherent stability of GC-rich DNA, primarily due to base stacking interactions that form stable and complex secondary structures, presents a formidable obstacle [6]. These structures, such as hairpins, knots, and tetraplexes, resist complete denaturation at standard PCR temperatures, hindering primer annealing and causing DNA polymerase to stall, which results in failed amplification, smeared gels, or truncated products [7] [8]. For researchers and drug development professionals aiming to clone, sequence, or analyze these critical regulatory sequences, overcoming these hurdles is essential. This application note details optimized protocols to robustly amplify GC-rich eukaryotic promoters, leveraging specialized reagents and tailored thermal cycling conditions.

Underlying Mechanisms and Experimental Visualization

The Biophysical Obstacles

The challenges of amplifying GC-rich templates are rooted in their molecular stability. A G-C base pair is stabilized by three hydrogen bonds, compared to the two found in an A-T pair, leading to a higher melting temperature (Tm) [7]. However, the primary source of stability is not hydrogen bonding but base stacking interactions, which make the DNA duplex exceptionally rigid and resistant to denaturation [6]. This thermal stability means that under standard PCR denaturation temperatures (e.g., 94–95°C), GC-rich regions, particularly those in eukaryotic promoters, may not fully denature. Consequently, these regions form stable intra-strand secondary structures that physically block the progression of the DNA polymerase [7] [8]. Furthermore, PCR primers designed for these regions are themselves GC-rich and prone to forming self-dimers, cross-dimers, and hairpin loops, leading to mispriming and inefficient amplification [6] [8].

Experimental Workflow for Diagnostics and Optimization

The following diagram illustrates a recommended diagnostic and optimization workflow for troubleshooting GC-rich PCR amplification. This structured approach helps researchers systematically identify the cause of amplification failure and apply targeted solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

A critical step in overcoming GC-rich amplification challenges is the selection of appropriate reagents. The following table catalogs key solutions and their functions, as validated by recent research.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Amplifying GC-Rich Promoters

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase (NEB), Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB), AccuPrime GC-Rich DNA Polymerase (ThermoFisher) | Engineered for processivity through stable secondary structures; often supplied with proprietary GC enhancer buffers [7] [6]. |

| PCR Additives | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Betaine, Formamide, 7-deaza-2′-deoxyguanosine | Disrupt base stacking and reduce DNA melting temperature, helping to denature secondary structures and improve primer annealing [7] [8] [5]. |

| Enhancer Buffers | Q-Solution, High GC Enhancer, Hi-Spec Additive | Proprietary buffer formulations that often contain a combination of additives to simultaneously inhibit secondary structure formation and increase primer stringency [7] [9]. |

| Hot-Start Enzymes | GoTaq G2 Hot Start Taq | An antibody-based inhibition system that prevents polymerase activity until initial denaturation, reducing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation [10]. |

Structured Experimental Protocols and Data

Optimized Protocol for GC-Rich Promoter Amplification

This protocol is synthesized from methodologies successfully applied to amplify the GC-rich promoter of the EGFR gene and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits [8] [5].

Reaction Setup

- Use a high-fidelity, GC-optimized DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5 or OneTaq). A master mix format is convenient, but a standalone polymerase offers more flexibility for optimization [7].

- Template DNA: Use a final concentration of at least 2 µg/mL. When working with challenging sources like FFPE tissue, higher DNA input may be necessary [5].

- Primers: Design primers with a Tm of 50–72°C. The annealing temperature (Ta) will be optimized, but initial calculations can be done using the NEB Tm Calculator [7].

- Additives: Include 5% DMSO and/or 1 M Betaine in the reaction mix. These can be used individually or in combination [8] [5].

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 30–60 seconds (or per polymerase instructions).

- Amplification Cycles (35–45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 5–10 seconds. For extremely stable templates, a higher temperature (e.g., 99°C) can be tested, but be mindful of polymerase half-life [6].

- Annealing: Use a gradient PCR to determine the optimal temperature. The optimal Ta is often 5–7°C higher than the calculated Tm for GC-rich targets [5]. Start with a gradient from 63°C to 72°C.

- Extension: 72°C for 20–30 seconds per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 2 minutes.

Post-Amplification Analysis

- Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. For cloning or sequencing applications, purify the product using a commercial PCR purification kit.

Quantitative Optimization Data

Systematic optimization of reaction components is crucial. The following table summarizes key experimental data from published optimization studies, providing a reference for your own experiments.

Table 2: Quantitative Data from GC-Rich PCR Optimization Studies

| Parameter Optimized | Tested Range | Optimal Value / Finding | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO Concentration | 1% to 5% [5] | 5% DMSO provided desired amplicon yield without non-specific amplification [5]. | Amplification of the EGFR promoter (GC content ~75-88%) [5]. |

| MgCl₂ Concentration | 0.5 mM to 4.0 mM [7] [5] | 1.5 mM to 2.0 mM was optimal for EGFR promoter [5]. A gradient of 0.5 mM increments between 1.0 and 4.0 mM is advised [7]. | EGFR promoter amplification and general GC-rich templates [7] [5]. |

| Annealing Temperature | Calculated Tm to Tm+10°C [5] | 7°C higher than the calculated Tm (63°C vs. 56°C) [5]. | EGFR promoter amplification [5]. |

| DNA Template Concentration | 0.25 to 28.20 µg/mL [5] | At least 2 µg/mL; samples below 1.86 µg/mL failed to amplify [5]. | DNA extracted from FFPE tissue [5]. |

| Combined Additives | DMSO (5%) and Betaine (1 M) | The combination of DMSO and betaine was more effective than either additive alone for a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit [8]. | Amplification of Ir-nAChRb1 (65% GC) and Ame-nAChRa1 (58% GC) [8]. |

Amplifying GC-rich eukaryotic promoter regions demands a departure from standard PCR protocols. There is no single universal solution; success is achieved through a systematic, multi-pronged optimization strategy [7]. As demonstrated in the protocols and data herein, this involves the selection of a specialized polymerase, the judicious use of chemical additives like DMSO and betaine, and the fine-tuning of physical parameters such as MgCl₂ concentration and annealing temperature. By adopting this rigorous approach, researchers can reliably overcome the obstacles posed by stable secondary structures, thereby accelerating foundational research and drug development programs focused on gene regulatory mechanisms.

The amplification and analysis of nucleic acids from complex biological samples are fundamental to molecular biology research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development. However, the accuracy and sensitivity of these analyses, particularly when working with eukaryotic promoter regions, are frequently compromised by the presence of PCR inhibitors. These inhibitory substances represent a heterogeneous class of compounds that originate from the sample matrix, target cells, or reagents added during sample preparation [11]. Their interference can lead to partial inhibition, resulting in the underestimation of target nucleic acids, or complete amplification failure [12]. Understanding the sources and mechanisms of these inhibitors is therefore critical for developing robust analytical protocols, especially in promoter studies where template quantities may be limited. This application note details the common sources of inhibition in complex samples and provides validated protocols to overcome these challenges in the context of eukaryotic promoter research.

Inhibitor Origins

PCR inhibitors can be categorized based on their origin, which directly informs the strategy for their mitigation.

- Clinical and Biological Samples: Blood contains potent inhibitors such as immunoglobulin G (IgG), which has a high affinity for single-stranded DNA, heme, and lactoferrin [11] [12]. Feces comprise a complex mixture of bile salts, bilirubin, and complex polysaccharides. Milk can inhibit PCR due to enzymes like plasmin that degrade DNA polymerases, as well as high calcium concentrations that competitively bind to the polymerase [12].

- Plant and Environmental Samples: Plant tissues often contain polysaccharides and polyphenolic compounds that co-purify with nucleic acids [12]. Soil and sediment samples are particularly challenging due to high concentrations of humic substances—degradation products of lignin that include humic acid and fulvic acid. These are heterogeneous groups of dibasic weak acids with carboxyl and hydroxyl groups that can interfere with the PCR reaction even at low concentrations [11].

- Sample Processing and Laboratory Sources: Reagents used during nucleic acid extraction, such as ionic detergents (e.g., SDS), EDTA, ethanol, and phenol, can become inhibitory if not thoroughly removed [12]. Furthermore, laboratory materials including glove powder, pollen, and certain types of plasticware can also introduce contaminants [12].

Mechanisms of Inhibition

Inhibitors can disrupt the amplification process at multiple stages, and a single inhibitor may operate through more than one mechanism. The key interference points are summarized in the diagram below.

The mechanisms can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Interaction with Nucleic Acids: Inhibitors like humic acids or nucleases can bind directly to single- or double-stranded DNA, modifying or degrading the template and making it unavailable for amplification [11] [12]. Polysaccharides may mimic DNA structure and disrupt the enzymatic process [12].

- Interaction with DNA Polymerase: Many inhibitors target the DNA polymerase itself. Proteases can degrade the enzyme, while substances like tannic acid, hematin, or collagen can block its active site [12]. Humic acids are known to interact with both the template and the polymerase, preventing the enzymatic reaction [11].

- Depletion of Essential Cofactors: The activity of DNA polymerase is magnesium-dependent. Compounds such as EDTA or tannic acid can chelate Mg²⁺ ions, making them unavailable for the polymerase and thereby reducing its activity [12]. High concentrations of calcium may also lead to competitive binding at the polymerase's active site [12].

- Interference with Fluorescence: In real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) or digital PCR (dPCR), some inhibitors can quench fluorescence or increase background noise, leading to inaccurate quantification [11] [12]. This is a particular concern for sequencing-by-synthesis technologies used in massively parallel sequencing (MPS) [11].

Quantitative Comparison of PCR Enhancement Strategies

A systematic evaluation of different inhibitor removal and enhancement strategies is crucial for protocol optimization. The following table summarizes the performance of various approaches in mitigating inhibition in wastewater samples, a complex matrix rich in inhibitors, providing a quantitative framework for decision-making [13].

Table 1: Evaluation of PCR Enhancement Strategies for Wastewater Samples

| Strategy | Concentration Tested | Key Findings (Cq Value Impact) | Effect on Viral Load Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Protocol (No Enhancer) | N/A | High inhibition; virus detected in only 1/3 undiluted samples [13] | Significant underestimation |

| 10-fold Dilution | N/A | Reduced inhibition; virus detected in all diluted samples [13] | Reduced sensitivity; potential underestimation |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 0.1% - 1.0% | No significant improvement over the basic protocol [13] | No notable enhancement |

| T4 gp32 Protein | 0.1 - 1 µM | No significant improvement over the basic protocol [13] | No notable enhancement |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 1% - 10% | No significant improvement over the basic protocol [13] | No notable enhancement |

| Formamide | 1% - 5% | No significant improvement over the basic protocol [13] | No notable enhancement |

| TWEEN-20 | 0.1% - 1.0% | No significant improvement over the basic protocol [13] | No notable enhancement |

| Glycerol | 1% - 10% | No significant improvement over the basic protocol [13] | No notable enhancement |

| Inhibitor Removal Kit | Commercial | Effectively reduced inhibition; most reliable results [13] | Most accurate quantification |

Recommended Protocols for Eukaryotic Promoter Amplification

The following protocols integrate the most effective strategies to ensure successful amplification of eukaryotic promoter regions from complex biological samples.

Protocol 1: Nucleic Acid Extraction and Purification from Challenging Samples

This protocol is designed for soil-rich or plant-derived samples, which are high in humic acids and polyphenols.

Materials:

- Sample material (e.g., soil, plant tissue)

- Lysis buffer (e.g., CTAB-based buffer for plants)

- Proteinase K

- Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol (25:24:1)

- Commercial inhibitor removal spin columns (e.g., kits designed for soil or stool)

- Isopropanol and 70% ethanol

- Nuclease-free water

Method:

- Homogenization and Lysis: Homogenize the sample in a suitable lysis buffer containing Proteinase K. Incubate at 56°C for 1-2 hours to ensure complete cell lysis and digestion of proteins.

- Organic Extraction: Add an equal volume of Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol to the lysate. Mix thoroughly and centrifuge to separate the phases. Carefully transfer the upper aqueous phase to a new tube. Note: Phenol is a potent inhibitor and must be completely removed in subsequent steps [12].

- Inhibitor Removal Column Purification: Pass the aqueous phase through a commercial inhibitor removal column as per the manufacturer's instructions. These columns contain a matrix specifically designed to bind polyphenolic compounds, humic acids, and other inhibitors [13].

- Nucleic Acid Precipitation: To the flow-through, add 0.7 volumes of isopropanol to precipitate the DNA. Centrifuge to pellet the DNA.

- Wash and Elute: Wash the pellet with 70% ethanol to remove residual salts and inhibitors. Air-dry the pellet and resuspend it in nuclease-free water.

- Quality Control: Assess the purity and concentration of the DNA using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios). The absence of a brownish tint indicates successful removal of humic acids.

Protocol 2: PCR Mix Formulation with Enhanced Tolerance

This protocol optimizes the amplification reaction itself by selecting a robust polymerase and including effective enhancers.

Materials:

- Purified DNA template

- Inhibitor-tolerant DNA polymerase (e.g., engineered Taq mutants, Tth or Tfl polymerase) [11] [12]

- Corresponding reaction buffer (Mg²⁺ included)

- dNTP mix

- Target-specific forward and reverse primers

- PCR enhancers: Betaine (1-1.3 M) and/or BSA (0.1-0.5 µg/µL)

Method:

- Polymerase Selection: Prepare the master mix using a DNA polymerase known for high inhibitor tolerance. For instance, polymerases from Thermus thermophilus (rTth) show significantly higher resistance to inhibitors in blood compared to standard Taq [12].

- Master Mix Formulation: Combine the following components in a sterile tube on ice:

- 10-50 ng purified DNA template

- 1X reaction buffer (provided with the polymerase)

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 0.2-0.5 µM of each primer

- 1.0 M Betaine

- 0.2 µg/µL BSA

- 0.5-1.0 U of DNA polymerase

- Nuclease-free water to the final volume (e.g., 20 µL).

- Amplification: Run the PCR using cycling conditions optimized for your primer set and template. The inclusion of betaine helps to reduce the formation of secondary structures, which is particularly beneficial for GC-rich promoter regions, and BSA can bind residual inhibitory compounds [12].

- Validation: Always include a positive control (inhibitor-free DNA) and a no-template control (NTC) to verify the efficacy of the reaction and rule out contamination.

The workflow for processing complex samples, from extraction to analysis, is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents essential for overcoming inhibition in the amplification of nucleic acids from complex samples.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Mitigating PCR Inhibition

| Reagent | Function/Mechanism | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor-Tolerant DNA Polymerase | Engineered enzyme with higher affinity for primer-template or resistance to specific inhibitors (e.g., from blood, humic acid) [11] [12]. | Crucial for direct PCR protocols; superior to standard Taq in complex matrices. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Binds to a wide range of inhibitors (phenolics, humic acids, tannins) [13] [12]. Acts as a competitive target for proteinases. | Effective at 0.1-0.5 µg/µL. A first-line additive for many sample types. |

| Betaine | Biologically compatible solute that reduces DNA secondary structure formation by lowering the strand separation temperature [12]. | Highly recommended for GC-rich templates like promoter regions; used at 1-1.3 M. |

| T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32) | Binds to single-stranded DNA, preventing the action of inhibitors and stabilizing the template [13] [12]. | Can be effective in fecal and environmental samples; cost may be a factor. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Lowers the melting temperature (Tm) of DNA, destabilizes secondary structures, and can enhance specificity [13]. | Common concentration is 1-10%. Can inhibit some polymerases at higher levels. |

| Commercial Inhibitor Removal Kits | Silica-based columns or magnetic beads with chemistries designed to selectively bind humic acids, polyphenols, and other contaminants [13] [11]. | Most reliable method for heavily inhibited samples; minimizes DNA loss compared to simple dilution. |

The successful amplification of eukaryotic promoter regions from complex biological samples is inherently challenged by the presence of diverse PCR inhibitors. A systematic approach that combines effective nucleic acid extraction, strategic purification using commercial kits, and optimized PCR formulation with tolerant polymerases and chemical enhancers is paramount. As demonstrated quantitatively, while many traditional enhancers may show limited efficacy, the use of specialized inhibitor removal kits and robust polymerase systems provides the most reliable path to accurate and sensitive results. By integrating these protocols and reagents, researchers can significantly improve the fidelity of their genetic analyses, thereby advancing studies in gene regulation, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development.

Defining PCR Enhancers and Their Primary Functions in Amplification

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) enhancers are a diverse class of chemical additives incorporated into reaction mixtures to improve the efficiency and specificity of DNA amplification, particularly for challenging templates. These compounds function through distinct biochemical mechanisms to overcome barriers that impede conventional PCR, such as high GC content, stable secondary structures, and the presence of enzyme inhibitors. The amplification of eukaryotic promoter regions, which are often characterized by high GC-content and complex secondary structures, presents a quintessential challenge where PCR enhancers provide critical assistance [14] [15]. By modulating DNA melting behavior, stabilizing polymerase enzymes, and neutralizing inhibitors, these additives have become indispensable tools in molecular biology research, diagnostic assay development, and pharmaceutical applications where robust and reliable nucleic acid amplification is required.

Mechanisms of Action and Performance Data

PCR enhancers improve amplification through several primary mechanisms. Some function as destabilizing agents that lower the melting temperature (Tm) of DNA, facilitating the denaturation of templates with high GC-content and preventing the formation of stable secondary structures. Others act as stabilizing agents that increase the thermal stability of DNA polymerases, preserving enzyme activity during high-temperature incubation steps. A third category comprises viscosity modifiers and inhibitor shields that reduce secondary structure formation or sequester contaminants that interfere with polymerase activity [14] [15] [16]. The effectiveness of a specific enhancer depends on its concentration, the characteristics of the target DNA, and the properties of the DNA polymerase being used.

Systematic comparisons of PCR enhancers have revealed their varying efficacies across different template types. The quantitative data below summarizes the performance of common enhancers in amplifying DNA fragments with moderate (53.8%), high (68.0%), and very high (78.4%) GC-content, as measured by real-time PCR cycle threshold (Ct) values and melting temperatures [14].

Table 1: Performance of PCR Enhancers Across Different GC-Content Templates

| Enhancer | Concentration | 53.8% GC (Ct±SEM) | 68.0% GC (Ct±SEM) | 78.4% GC (Ct±SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | - | 15.84±0.05 | 15.48±0.22 | 32.17±0.25 |

| DMSO | 5% | 16.68±0.01 | 15.72±0.03 | 17.90±0.05 |

| Formamide | 5% | 18.08±0.07 | 15.44±0.03 | 16.32±0.05 |

| Betaine | 0.5 M | 16.03±0.03 | 15.08±0.10 | 16.97±0.07 |

| Trehalose | 0.4 M | 16.43±0.16 | 15.15±0.08 | 16.91±0.14 |

| Sucrose | 0.4 M | 16.39±0.09 | 15.03±0.04 | 16.67±0.08 |

Table 2: Recommended Enhancer Cocktails for Challenging Templates

| Target Template | Recommended Formulation | Primary Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| GC-rich eukaryotic promoters | 1 M Betaine | Effective denaturation of stable DNA secondary structures |

| Long DNA fragments with GC-rich regions | 0.5 M Betaine + 0.2 M Sucrose | Combined destabilizing and stabilizing effects with minimal negative impact |

| Inhibitor-containing samples | Betaine or Trehalose | Enhanced polymerase stability and inhibitor tolerance |

| Difficult templates requiring high specificity | Proprietary enhancer cocktails | Multiple mechanisms of action for reliable amplification |

The data demonstrates that while enhancers may slightly reduce amplification efficiency for moderate GC-content templates (as indicated by higher Ct values), they provide substantial benefits for GC-rich targets. Betaine, sucrose, and trehalose have emerged as particularly effective enhancers, often surpassing traditional additives like DMSO and formamide in recent studies [14] [17]. Betaine outperforms other enhancers in the amplification of GC-rich DNA fragments, thermostabilizing Taq DNA polymerase, and inhibitor tolerance, while sucrose and trehalose show similar thermostabilization effects with milder inhibitory effects on normal PCR [14].

Application Notes for Eukaryatic Promoter Amplification

Eukaryotic promoter regions represent particularly challenging targets for PCR amplification due to their characteristically high GC-content, which promotes the formation of stable secondary structures and impedes complete denaturation. These regions often contain CpG islands, palindromic sequences, and hairpin structures that interfere with primer annealing and polymerase progression. Successful amplification of these sequences requires strategic selection and optimization of PCR enhancers to overcome these inherent challenges [14] [15].

For typical eukaryotic promoter regions (GC-content >70%), a combination of 1 M betaine with 0.1-0.2 M sucrose has demonstrated superior performance in both specificity and yield. Betaine functions as a helix destabilizer that equalizes the thermal stability of AT and GC base pairs, facilitating denaturation of GC-rich templates, while sucrose provides additional stabilization for the DNA polymerase without significantly increasing reaction viscosity. This combination maintains the enzyme's processivity while ensuring complete template denaturation at each cycle [14]. For promoter regions with extremely high GC-content (>80%) or those containing tandem repeats, the addition of 2-5% DMSO may further improve amplification efficiency, though this should be carefully titrated as DMSO can inhibit Taq polymerase at higher concentrations [15] [16].

When working with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) samples or other complex DNA preparations for promoter studies, enhancers that provide both destabilizing and inhibitor-shielding properties are recommended. Betaine (0.5-1 M) and trehalose (0.2-0.4 M) have shown particular efficacy in these applications, as they enhance amplification efficiency while tolerating common contaminants that may be present in sample preparations [14]. For long-range PCR amplification of extended promoter regions (>5 kb), specialized polymerase systems with proofreading activity combined with betaine (1-1.5 M) typically yield the best results, as this combination addresses both the structural challenges of the template and the processivity requirements for long amplification products [15] [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard PCR with Enhancers for GC-Rich Eukaryotic Promoters

This protocol is optimized for amplifying eukaryotic promoter regions with high GC-content (70-85%) in a standard 50 µL reaction volume.

Reagents and Working Solutions:

- 10X PCR Buffer (supplied with polymerase)

- 25 mM MgCl₂ solution

- 10 mM dNTP mix

- Forward and reverse primers (10 µM each)

- Template DNA (10-100 ng genomic DNA or 1-10 ng plasmid DNA)

- DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq DNA polymerase, 5 U/µL)

- 5 M Betaine stock solution (prepare in nuclease-free water)

- 1 M Sucrose stock solution (prepare in nuclease-free water)

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Prepare a master mix on ice with the following components:

- 5 µL 10X PCR Buffer

- 3 µL 25 mM MgCl₂ (final 1.5 mM)

- 1 µL 10 mM dNTP mix (final 0.2 mM each)

- 2.5 µL Forward primer (10 µM)

- 2.5 µL Reverse primer (10 µM)

- 10 µL 5 M Betaine (final 1 M)

- 5 µL 1 M Sucrose (final 0.1 M)

- 0.5 µL DNA polymerase (5 U/µL)

- 18.5 µL Nuclease-free water

- 2 µL Template DNA

Mix gently by pipetting and centrifuge briefly to collect contents at the bottom of the tube.

Transfer tubes to a thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes

- 35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 60-68°C (optimize based on primer Tm) for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of expected product

- Final extension: 72°C for 5 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

Analyze 5-10 µL of PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If non-specific amplification occurs, increase the annealing temperature by 2-3°C or reduce the betaine concentration to 0.5 M.

- If yield remains low, consider a touchdown PCR approach or increase extension time to 2 minutes per kb.

- For promoter regions with extremely high GC-content (>85%), include an initial denaturation step at 98°C for 1 minute in each cycle.

Protocol 2: Enhanced Long-Range PCR of Promoter Regions

This protocol is specifically designed for amplifying extended eukaryotic promoter regions (>5 kb) with high GC-content, utilizing a specialized polymerase system and enhanced conditions.

Reagents and Working Solutions:

- Commercial long-range PCR buffer system

- 25 mM MgCl₂ solution

- 10 mM dNTP mix

- Forward and reverse primers (10 µM each)

- Template DNA (50-200 ng genomic DNA)

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase mix (e.g., combination of non-proofreading and proofreading enzymes)

- 5 M Betaine stock solution

- 50% Glycerol solution (prepare in nuclease-free water)

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Prepare a master mix on ice with the following components:

- 10 µL 5X Long-range PCR Buffer

- 4 µL 25 mM MgCl₂ (final 2 mM)

- 2 µL 10 mM dNTP mix (final 0.2 mM each)

- 3 µL Forward primer (10 µM)

- 3 µL Reverse primer (10 µM)

- 12.5 µL 5 M Betaine (final 1.25 M)

- 2 µL 50% Glycerol (final 2%)

- 1 µL DNA polymerase mix

- 10.5 µL Nuclease-free water

- 2 µL Template DNA

Mix gently by pipetting and centrifuge briefly.

Transfer tubes to a thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 10 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 60-65°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 6-8 minutes (depending on product length)

- 25 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 60-65°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 6-8 minutes (with 20-second increment per cycle)

- Final extension: 68°C for 10 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis, using appropriate molecular weight markers.

Technical Notes:

- The combination of betaine and glycerol enhances both DNA denaturation and polymerase stability, critical for long amplicons with complex secondary structures.

- The two-stage cycling program with incremental extension times enhances the yield of longer products by allowing complete extension of target sequences.

- For promoter regions exceeding 10 kb, extend the initial extension times to 10-12 minutes and increase the number of cycles in the second stage to 30.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PCR Enhancement Studies

| Reagent | Typical Working Concentration | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | 0.5-1.5 M | Equalizes DNA template melting temperatures; reduces secondary structure formation | Particularly effective for GC-rich eukaryotic promoters; enhances specificity and yield |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 2-10% | Disrupts base pairing; reduces DNA secondary structure | Use at lower concentrations (2-5%) for GC-rich templates; higher concentrations inhibit polymerase |

| Trehalose | 0.2-0.4 M | Thermally stabilizes DNA polymerase; enhances inhibitor resistance | Effective in multiplex PCR and with inhibitor-containing samples; improves enzyme half-life |

| Sucrose | 0.1-0.4 M | Stabilizes DNA polymerase; modest reduction of DNA melting temperature | Often used in combination with betaine; minimal negative effects on standard PCR |

| Formamide | 1-5% | Lowers DNA melting temperature; destabilizes DNA duplex | Effective for extremely GC-rich targets; can inhibit polymerase at higher concentrations |

| Tetramethylammonium Chloride (TMAC) | 15-60 µM | Increases primer annealing specificity; eliminates non-specific priming | Preferred for reactions with degenerate primers; enhances hybridization stringency |

| Glycerol | 5-10% | Reduces secondary structures; stabilizes enzyme activity | Improves amplification of long targets; increases reaction viscosity |

| Commercial Enhancer Cocktails | Manufacturer specified | Multiple mechanisms; often proprietary formulations | Optimized for specific applications; convenient but more expensive than individual components |

PCR enhancers represent powerful tools for overcoming the inherent challenges of amplifying difficult templates, particularly eukaryotic promoter regions characterized by high GC-content and complex secondary structures. Through their diverse mechanisms of action—including DNA destabilization, enzyme stabilization, and inhibitor neutralization—these compounds significantly expand the capabilities of PCR technology in research and diagnostic applications. The systematic evaluation of enhancer performance across different template types provides a rational basis for selection and optimization, with betaine, sucrose, and trehalose emerging as particularly effective options in recent comparative studies. As molecular applications continue to evolve toward more challenging targets, including non-coding regulatory regions and complex genomic architectures, the strategic implementation of PCR enhancers will remain an essential component of robust experimental design in molecular biology, biomedical research, and pharmaceutical development.

A Practical Toolkit: Selecting and Using PCR Enhancers for Promoter Amplification

Core PCR Components and Setup for Promoter Regions

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a fundamental laboratory technique for amplifying specific DNA sequences, revolutionizing molecular biology since its invention by Kary Mullis in 1983 [18] [19]. While standard PCR protocols work effectively for many DNA targets, amplifying eukaryotic promoter regions presents unique challenges that require specialized approaches. These genomic regions frequently exhibit high GC content, complex secondary structures, and unique sequence characteristics that complicate primer design and amplification efficiency [15]. Successfully amplifying these difficult sequences depends on optimizing core PCR components and incorporating specialized enhancers that address these specific challenges. This application note provides detailed methodologies for researchers aiming to amplify promoter regions, with particular emphasis on component optimization and experimental protocols validated for GC-rich templates.

Core PCR Components and Their Optimization

Essential Reaction Components

A standard PCR reaction requires several core components, each playing a critical role in the amplification process. Understanding the function and optimal concentration of each component is essential for successful amplification of challenging promoter regions.

Table 1: Core PCR Components and Their Optimal Concentrations

| Component | Function | Recommended Concentration | Special Considerations for Promoter Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | Provides the target sequence for amplification | 0.1–1 ng (plasmid), 5–50 ng (gDNA) in 50 μL reaction [20] | Higher purity required; consider GC content and complexity |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands | 1–2 units per 50 μL reaction [20] | Use high-fidelity, GC-rich compatible enzymes for promoter regions |

| Primers | Bind flanking sequences to define amplification region | 0.1–1 μM each [20] | Design with Tm 55–70°C; avoid secondary structures; critical for specificity |

| dNTPs | Building blocks for new DNA strands | 0.2 mM each dNTP [20] | Balanced concentrations crucial; consider GC-content when optimizing |

| Magnesium Ions (Mg²⁺) | Cofactor for DNA polymerase activity | 1.5–2.5 mM (requires optimization) [20] | Concentration significantly affects specificity; titrate for each new promoter target |

| Buffer System | Maintains optimal pH and ionic conditions | 1X concentration | May require specialized formulations for GC-rich regions |

Component-Specific Optimization Strategies

Template DNA quality and quantity significantly impact PCR success. For promoter region amplification, DNA purity is paramount as contaminants can inhibit polymerization. The template amount should be optimized based on source: 0.1–1 ng for plasmid DNA and 5–50 ng for genomic DNA in a standard 50 μL reaction [20]. When working with eukaryotic genomic DNA, ensure complete dissolution and avoid shearing during preparation.

DNA polymerase selection depends on template characteristics. While Taq polymerase remains popular for standard applications, promoter regions often benefit from specialized polymerases with proofreading capabilities and enhanced processivity through GC-rich regions [20]. Engineerized polymerases with higher affinity for templates may require less input DNA and perform better with complex secondary structures common in promoter regions.

Primer design represents the most critical factor for specific amplification of promoter regions. Follow these key principles:

- Length: 15–30 nucleotides [20]

- Melting Temperature (Tm): 55–70°C, with forward and reverse primers within 5°C of each other [20]

- GC Content: 40–60% with uniform distribution [20]

- 3' End Specificity: Avoid more than three G or C bases at the 3' end to minimize nonspecific priming [20]

- Secondary Structures: Check for self-complementarity, primer-dimers, and hairpins using bioinformatics tools

For promoter regions with particularly high GC content, consider increasing primer length slightly to achieve higher Tm without exceeding 60% GC content. Additionally, incorporate non-template sequences such as restriction sites at the 5' ends when planning downstream cloning applications [20].

dNTPs and Magnesium Concentration optimization requires careful balancing. The recommended concentration for each dNTP is 0.2 mM, though this may be adjusted for specific promoter regions [20]. Higher dNTP concentrations can inhibit PCR, while concentrations below 0.01 mM may limit polymerization efficiency. Magnesium ions (Mg²⁺) serve as essential cofactors for DNA polymerase activity by facilitating primer-template binding and catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation [20]. The optimal Mg²⁺ concentration typically ranges from 1.5–2.5 mM but must be determined empirically for each new promoter target, as it influences both specificity and yield.

PCR Enhancers for Challenging Promoter Regions

Types and Mechanisms of PCR Enhancers

PCR enhancers are additives that improve amplification efficiency, particularly for difficult templates like eukaryotic promoter regions. These compounds work through various mechanisms to overcome barriers to amplification.

Table 2: Common PCR Enhancers and Their Applications for Promoter Regions

| Enhancer | Mechanism of Action | Recommended Concentration | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | Reduces DNA melting temperature; equalizes Tm difference between AT- and GC-rich regions [15] | 0.5–1.5 M | Extremely GC-rich promoter regions (>70% GC) |

| DMSO | Disrupts base pairing; prevents secondary structures [15] | 3–10% (v/v) | Promoters with strong secondary structures |

| Formamide | Lowers strand separation temperatures [15] | 1–5% (v/v) | Complex promoter architectures |

| Glycerol | Stabilizes DNA polymerase; improves enzyme processivity [15] | 5–15% (v/v) | Long promoter regions (>1 kb) |

| BSA | Binds inhibitors; increases reaction stability [15] | 0.1–1 μg/μL | Crude DNA preparations |

Enhancer Selection and Optimization

Betaine (also known as N,N,N-trimethylglycine) is particularly valuable for GC-rich promoter regions as it reduces the melting temperature difference between AT- and GC-rich regions, effectively normalizing the amplification efficiency across the entire template [15]. This property makes it indispensable for promoter regions with GC content exceeding 70%.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) enhances PCR amplification by disrupting base pairing and preventing the formation of secondary structures that commonly occur in promoter regions [15]. For most applications, 5% DMSO provides significant improvement without inhibiting polymerase activity. However, some polymerases are sensitive to DMSO, requiring concentration optimization.

For particularly challenging promoter regions, enhancer cocktails often outperform individual additives. A combination of betaine (1 M), DMSO (5%), and 7-deaza-dGTP (as a partial substitute for dGTP) has proven effective for amplifying extremely GC-rich targets [15] [21]. When using enhancer cocktails, note that some proprietary PCR master mixes already contain optimized enhancer combinations, which should be considered when designing experiments.

Experimental Protocols

Standard PCR Protocol for Promoter Regions

This protocol provides a robust starting point for amplifying most eukaryotic promoter regions. Optimization may be required for specific targets.

Reagent Setup (50 μL Reaction)

- 10 μL 5X HF Buffer [22]

- 1 μL dNTPs (10 mM each) [22]

- 1 μL Phusion Polymerase (or other high-fidelity polymerase) [22]

- 2.5 μL Forward Primer (10 μM)

- 2.5 μL Reverse Primer (10 μM)

- 1 μL Betaine (5 M stock)

- 1.5 μL DMSO

- 30.5 μL Nuclease-free Water

- 50 ng Genomic DNA Template

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 30 seconds [22]

- Amplification (30–35 cycles):

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 minutes [22]

- Hold: 4°C indefinitely

Critical Step Notes:

- Annealing temperature should be optimized for each primer set; start 3–5°C below the calculated Tm [22]

- Extension time depends on amplicon length; allow 15–30 seconds per 500 bp for complex regions

- For promoter regions >1 kb, increase extension time to 45–60 seconds per kb

Advanced Protocol for GC-Rich Promoter Regions

For exceptionally challenging GC-rich promoter regions (>75% GC content), this enhanced protocol incorporates multiple optimization strategies.

Reagent Setup (50 μL Reaction)

- 10 μL 5X GC Buffer

- 1 μL dNTPs (10 mM each)

- 1 μL High-Fidelity GC-Rich Polymerase

- 2.5 μL Forward Primer (10 μM)

- 2.5 μL Reverse Primer (10 μM)

- 3 μL Betaine (5 M stock) - Final concentration 1 M

- 2.5 μL DMSO - Final concentration 5%

- 0.5 μL 7-deaza-dGTP (optional, for extreme GC content)

- 27 μL Nuclease-free Water

- 50 ng Genomic DNA Template

Thermal Cycling Conditions with Touchdown

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2 minutes

- 5 Cycles:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds

- Annealing: 70°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 45 seconds per kb

- 5 Cycles:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds

- Annealing: 68°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 45 seconds per kb

- 25 Cycles:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds

- Annealing: 65°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 45 seconds per kb

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 minutes

- Hold: 4°C indefinitely

Visualization of PCR Component Interactions

PCR Component Interaction Diagram. This visualization illustrates how core PCR components interact to produce amplified promoter regions. Template DNA provides the target sequence, while primers define amplification boundaries. DNA polymerase catalyzes DNA synthesis using dNTPs as building blocks, with magnesium ions as essential cofactors. The buffer maintains optimal conditions, and enhancers facilitate amplification of challenging sequences.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem Identification and Resolution

No Amplification

- Potential Causes: Insufficient template quality, primer binding issues, incorrect Mg²⁺ concentration, inhibitory contaminants

- Solutions: Verify template quality and concentration; check primer design for complementarity to target; titrate Mg²⁺ concentration (1–4 mM range); add BSA (0.1 μg/μL) to bind potential inhibitors [20] [15]

Nonspecific Bands

- Potential Causes: Primer dimers, low annealing temperature, excessive enzyme concentration, high primer concentration

- Solutions: Increase annealing temperature (2–5°C increments); optimize primer concentration (0.1–0.5 μM); use hot-start polymerase; employ touchdown PCR; reduce cycle number [20]

Weak or No Bands for GC-Rich Promoters

- Potential Causes: Incomplete denaturation, secondary structures, polymerase stalling

- Solutions: Incorporate betaine (1 M final concentration); add DMSO (3–8%); use GC-rich optimized polymerase; extend denaturation time; include 7-deaza-dGTP; implement a touchdown protocol [15] [21]

Optimization Workflow

PCR Troubleshooting Workflow. This diagram outlines a systematic approach to resolving common PCR amplification issues with promoter regions. Begin by verifying template quality and primer design, then progress through component optimization steps before introducing specialized enhancers for challenging targets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Promoter Region PCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, Taq DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity enzymes preferred for cloning applications; hot-start versions reduce nonspecific amplification [20] |

| PCR Enhancers | Betaine, DMSO, Formamide, BSA, Glycerol | Improve amplification of GC-rich templates; reduce secondary structures; stabilize reaction components [15] |

| Specialized dNTPs | 7-deaza-dGTP, dUTP (for carryover prevention) | 7-deaza-dGTP reduces secondary structures in GC-rich regions; dUTP with UDG treatment prevents amplicon contamination [20] |

| Buffer Systems | GC Buffer, HF Buffer, Standard PCR Buffer | Specialized buffers maintain polymerase activity and DNA stability under different conditions; GC buffers specifically designed for high GC content [23] |

| PCR Master Mixes | PACE Genotyping Master Mix, ProbeSure Master Mix, GC-Rich Master Mixes | Pre-mixed solutions provide consistency and convenience; contain optimized ratios of polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and enhancers [23] |

When selecting reagents for promoter region amplification, consider the specific challenges of your target sequence. For routine amplification of moderate GC content promoters, standard high-fidelity polymerases with appropriate buffers may suffice. However, for extreme GC content (>75%) or long promoter regions (>2 kb), invest in specialized polymerase systems specifically engineered for these challenging templates. Commercial PCR master mixes can significantly improve reproducibility, especially for high-throughput applications, as they provide standardized reaction conditions and reduce pipetting errors [23].

Within molecular biology research, the amplification of eukaryotic promoter regions is a critical step for understanding transcriptional regulation, a process with significant implications for drug development and genetic research. However, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of these regions is often hampered by their characteristically high GC content, which promotes the formation of stable secondary structures that impede DNA polymerase progression [24]. This technical challenge necessitates the use of specialized PCR enhancers. This application note details the function, optimization, and practical application of four common enhancers—Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO), Betaine, Formamide, and Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)—framed within the context of amplifying GC-rich eukaryotic promoter sequences. The protocols and data presented herein provide life science researchers and drug development professionals with a validated framework to overcome a persistent obstacle in molecular biology.

Enhancer Mechanisms and Quantitative Data

PCR enhancers act through distinct biochemical mechanisms to facilitate the amplification of difficult templates. The following table summarizes the primary functions, optimal concentrations, and key considerations for DMSO, Betaine, Formamide, and BSA.

Table 1: Catalog of Common PCR Enhancers for GC-Rich DNA Amplification

| Enhancer | Primary Mechanism of Action | Optimal Concentration Range | Key Advantages | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Disrupts DNA secondary structure by reducing hydrogen bonding, thereby lowering the melting temperature (Tm) of DNA [25] [26]. | 2–10% (v/v) [25] [16] | Highly effective for GC-rich templates; widely available [25]. | Reduces Taq polymerase activity; requires concentration optimization to balance structure disruption with enzyme inhibition [25] [26]. |

| Betaine | Reduces formation of secondary structures and eliminates base-pair composition dependence of DNA melting; acts as an osmoprotectant [24] [25]. | 0.5–1.7 M [24] [25] | Can enhance specificity; particularly effective for GC-rich sequences [24] [26]. | Use Betaine or Betaine monohydrate, not Betaine HCl, to avoid pH changes [25]. |

| Formamide | Binds to DNA grooves, destabilizing the double helix and lowering melting temperature, which can improve specificity [25] [27]. | 1–5% (v/v) [25] [16] | Can increase hybridization stringency, reducing non-specific amplification [25]. | Effectiveness decreases for fragments >2.5 kb; has a narrow optimal concentration range [27]. |

| BSA | Binds to impurities and inhibitors (e.g., phenolic compounds) in the reaction, neutralizing their effects on the DNA polymerase [28] [27]. | 0.1–0.8 mg/mL [28] [25] | Combats PCR inhibitors; stabilizes DNA polymerase; cost-effective [28] [27]. | Enhances yield when co-used with DMSO or formamide; may require fresh addition in long cycles [27]. |

The synergistic use of these enhancers can be particularly powerful. Research has demonstrated that combining BSA with organic solvents like DMSO or formamide produces a co-enhancing effect, significantly boosting the amplification yield of GC-rich targets across a broad size range, from 0.4 kb to 7.1 kb [27]. This synergy allows for a reduction in the required concentration of organic solvents, which can be beneficial for downstream applications like cloning or sequencing.

Table 2: Synergistic Effect of BSA and DMSO on Amplification Yield

| Cycle Number | DMSO Alone | DMSO + BSA | Yield Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Cycles | Baseline | +10.5% to +22.7% | Significant early boost |

| 15 Cycles | Baseline | +10.5% to +22.7% | Maintained enhancement |

| 30 Cycles | Baseline | No further yield increase | BSA effect is early-cycle |

The enhancing effect of BSA is most pronounced in the initial PCR cycles, with yield increases of 10.5% to 22.7% observed within the first 15 cycles, after which its effect plateaus, potentially due to thermal denaturation [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for GC-Rich Promoter Amplification

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully amplified a 71% GC-rich putative mouse promoter region of 875 bp [24]. It provides a robust starting point for amplifying challenging eukaryotic promoter sequences.

Procedure:

Reaction Mixture Assembly: Combine the following components in a sterile PCR tube on ice to a final volume of 50 µL:

- Buffer and Cofactors: 1X PCR buffer AMS (composed of 750 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 200 mM (NH₄)₂SO₄, 0.1% Tween 20) [24]. Note: Alternatively, Pfu buffer can be used.

- Magnesium: 4 mM MgCl₂ [24].

- Nucleotides: 0.2 mM of each dNTP (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) [20].

- Primers: 0.1–1 µM of each forward and reverse primer, designed to flank the eukaryotic promoter region of interest [20].

- DNA Polymerase: 1–2 units of a thermostable DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq or a high-fidelity blend) [20].

- Template: 10–50 ng of high-quality genomic DNA (gDNA) [20].

- Enhancers: Add the enhancer cocktail:

Thermal Cycling: Place the tube in a thermal cycler and run the following program, optimized for a 875 bp GC-rich target [24]:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 minutes.

- Amplification Cycles (20-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 94°C for 10–30 seconds.

- Annealing: 56–66°C for 30 seconds. Note: A touchdown protocol can be used, starting at a higher annealing temperature and decreasing by 0.5°C per cycle for the first 20 cycles to enhance specificity [24].

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kilobase of amplicon length.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

Product Analysis: Analyze the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis to verify the size and specificity of the amplified promoter region.

Protocol 2: Additive Titration for Optimization

Given that the optimal concentration of enhancers is template- and primer-specific, systematic titration is recommended for novel promoter targets.

Procedure:

- Prepare a master reaction mix containing all standard components (buffer, dNTPs, primers, enzyme, template).

- Aliquot the master mix into multiple tubes.

- To each tube, add a different combination or concentration of enhancers. For example:

- Run the PCR amplification using the thermal cycling parameters from Protocol 1.

- Compare the yield and specificity of the amplification products via gel electrophoresis to determine the optimal enhancer formulation for your specific target.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and their specific functions in the amplification of GC-rich eukaryotic promoter regions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for GC-Rich PCR

| Reagent | Specific Function in GC-Rich PCR | Example Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Sulfate (NH₄)₂SO₄-based Buffer | Provides a alternative cation source that can enhance specificity and reduce spurious primer extension compared to Tris-HCl buffers [24]. | Used in PCR Buffer AMS for successful amplification of mouse PeP promoter [24]. |

| Betaine (1-1.7 M) | Equalizes the thermodynamic stability of GC and AT base pairs, facilitating strand separation and primer annealing in high-GC regions [24] [25]. | Core component of the enhancer cocktail for amplifying a 71% GC-rich promoter [24]. |

| DMSO (2-10%) | Disrupts hydrogen bonding in DNA secondary structures, preventing the formation of stable hairpins and loops that block polymerase progression [24] [25]. | Core component of the enhancer cocktail; requires balancing with potential Taq inhibition [24]. |

| BSA (0.1-0.8 mg/mL) | Acts as a molecular scavenger, binding to inhibitors that may be present in the template DNA or reaction components, thereby protecting the DNA polymerase [28] [27]. | Used as a co-enhancer with DMSO to significantly boost yield of GC-rich fragments [27]. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase Blends | Mixtures of non-proofreading and proofreading enzymes (e.g., Taq and Pfu) enhance processivity and accuracy over long or complex templates [10]. | Recommended for long-range PCR or when high fidelity is critical for downstream analysis. |

| MgCl₂ (1-4 mM) | Serves as an essential cofactor for DNA polymerase; its concentration critically affects enzyme activity, fidelity, and primer annealing [20] [25]. | Optimized at 4 mM for the amplification of the mouse PeP promoter [24]. |

The strategic use of PCR enhancers is indispensable for the successful amplification of GC-rich eukaryotic promoter regions, a common challenge in research aimed at elucidating transcriptional mechanisms. DMSO, Betaine, Formamide, and BSA each offer distinct advantages, with DMSO and Betaine directly combating secondary structures, and BSA providing stability and neutralizing inhibitors. Critically, the synergistic combination of BSA with organic solvents like DMSO provides a powerful, cost-effective strategy to significantly boost amplification yield, as demonstrated in the protocols herein. By applying the optimized conditions and systematic approaches outlined in this application note, researchers can reliably overcome the technical barriers associated with GC-rich DNA, thereby accelerating progress in gene regulation studies and drug discovery pipelines.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet the amplification of complex DNA regions—such as GC-rich sequences, long fragments, or templates from inhibitory samples—remains a significant challenge [15]. These barriers often lead to PCR failure, resulting in poor yield, specificity, or false negatives [8]. PCR enhancers are a diverse class of additives that mitigate these challenges through distinct biochemical mechanisms, enabling successful amplification where standard protocols fail [15]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals, particularly when working with difficult templates like eukaryotic promoter regions, which are often GC-rich and contain complex secondary structures [8]. This application note details the types, mechanisms, and practical application of PCR enhancers to overcome common amplification barriers, providing structured protocols for their use in demanding research contexts.

Common PCR Barriers and Enhancer Solutions

Amplification barriers frequently arise from the physicochemical properties of the template DNA, the composition of the sample, or the reaction conditions themselves. The table below summarizes the primary barriers and the corresponding types of enhancers used to address them.

Table 1: Common PCR Barriers and Corresponding Enhancer Solutions

| Amplification Barrier | Description of the Challenge | Recommended Enhancer Types |

|---|---|---|

| High GC Content & Secondary Structures | GC-rich sequences (>60%) form strong hydrogen bonds and stable secondary structures (e.g., hairpins), preventing complete denaturation and primer annealing [15] [8]. | Betaine, DMSO, Formamide, 7-deaza-dGTP [15] [8] |

| Long-Range Amplification | Amplifying long DNA fragments (>5 kb) is inefficient due to polymerase stalling, incomplete elongation, and higher susceptibility to template damage [15]. | Polymerase-stabilizing additives (e.g., glycerol), helicases, recombinases, nucleotide analogs [15] |

| Sample-Derived Inhibition | Complex biological samples (e.g., wastewater, tissue) contain inhibitors like humic acids, polyphenolics, or heparin that chelate essential cofactors or degrade nucleic acids [13]. | Proteins (BSA, gp32), detergents (Tween 20) [13] |

| Non-Specific Amplification & Primer-Dimer Formation | Low annealing stringency leads to mis-priming on off-target sites, generating non-specific products and primer-dimers that consume reaction resources [15] [29]. | Hot-start polymerases, cosolvents like DMSO, betaine [15] [29] |

Mechanisms of Action of Major PCR Enhancer Classes

PCR enhancers operate through specific biochemical mechanisms to overcome the barriers outlined above. The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms of four key enhancer classes.

Helix-Destabilizing Agents

Betaine (also known as trimethylglycine) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) are among the most widely used helix-destabilizing agents. They function by directly interacting with the DNA template to lower its melting temperature (Tm), which facilitates denaturation.

Betaine:

- Mechanism: Betaine distributes preferentially to the minor groove of DNA, where it disrupts the base-stacking interactions and weakens the stable, cooperative hydrogen-bonding network of GC base pairs [15]. This action effectively equalizes the thermodynamic stability of GC and AT base pairs, making the entire DNA strand more uniform and easier to denature [15].

- Application: Particularly effective for amplifying GC-rich regions (e.g., eukaryotic promoters). It is often used at a concentration of 0.5–1.5 M [15] [8].

DMSO:

- Mechanism: DMSO is a polar solvent that disrupts the secondary structure of single-stranded DNA and reduces the overall Tm of the duplex. It also prevents the formation of intra-strand secondary structures that can block polymerase progression [15] [13]. Furthermore, DMSO can increase reaction stringency by reducing the stability of mismatched primer-template hybrids, thereby improving specificity [15].

- Application: Standard working concentration is typically 2–10% (v/v). It is a common component in enhancer cocktails for long-range and GC-rich PCR [13] [8].

Proteins and Polymerase-Stabilizing Additives

This class of enhancers works by protecting the DNA polymerase or the nucleic acid template from damage or inhibition.

Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and T4 Gene 32 Protein (gp32):

- Mechanism: These proteins act as "molecular sponges." BSA non-specifically binds to inhibitors commonly found in complex samples (e.g., humic acids, polyphenolics, tannins), preventing them from interacting with and inhibiting the DNA polymerase [13]. gp32 is a single-stranded DNA-binding protein that coats the template, preventing the reannealing of DNA strands and the formation of secondary structures, thereby facilitating polymerase processivity [13].

- Application: BSA is commonly used at 0.1–1.0 μg/μL, especially in environmental or clinical sample analysis [13].

Glycerol:

- Mechanism: Glycerol acts as a stabilizing agent for the DNA polymerase enzyme. By reducing molecular motion and preventing protein aggregation, it helps maintain polymerase activity and fidelity, particularly during the high-temperature steps of PCR. This is especially beneficial for long-range PCR, where enzyme stability over longer extension times is critical [15] [13].

- Application: Often used at 5–10% (v/v) [13].

Detergents and Solubilizing Agents

- Non-Ionic Detergents (e.g., Tween 20):

- Mechanism: These surfactants reduce surface tension and prevent the adsorption of enzymes and nucleic acids to the walls of the reaction tube. They also help to solubilize hydrophobic contaminants and prevent the aggregation of proteins, including the DNA polymerase, ensuring a more efficient and uniform reaction [15] [13].

- Application: Typically used at low concentrations, around 0.1% (v/v) [13].

Quantitative Comparison of PCR Enhancers

The effectiveness of an enhancer depends on the specific barrier and the template. The following table provides a comparative overview of standard working concentrations, key mechanisms, and primary applications for major enhancers.

Table 2: Quantitative Profile and Applications of Common PCR Enhancers

| Enhancer | Standard Working Concentration | Primary Mechanism of Action | Optimal For | Potential Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|