Comparative Screening for STAT-Specific Inhibitors: Strategies, Challenges, and Clinical Pipeline Insights

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of comparative screening methodologies for developing specific Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) inhibitors.

Comparative Screening for STAT-Specific Inhibitors: Strategies, Challenges, and Clinical Pipeline Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of comparative screening methodologies for developing specific Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) inhibitors. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of STAT proteins, evaluates traditional and cutting-edge screening approaches, and addresses critical challenges in achieving STAT-isoform specificity. The content covers functional cell-based assays, virtual screening, and emerging machine learning techniques, while examining validation strategies and the current clinical pipeline. With over 22 STAT-targeted therapies in development, this review synthesizes key insights to guide the discovery of next-generation inhibitors for cancer, inflammatory diseases, and autoimmune disorders.

STAT Proteins as Therapeutic Targets: Biology, Structure, and Disease Implications

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) protein family represents a group of intracellular transcription factors that mediate numerous aspects of cellular immunity, proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation [1]. Discovered more than a quarter-century ago as crucial components of interferon signaling, STAT proteins constitute a rapid membrane-to-nucleus signaling module that induces the expression of various critical mediators of cancer and inflammation [2]. More than 50 cytokines and growth factors utilize the JAK-STAT pathway, making it a central communication node in cellular function [2]. The STAT family comprises seven members in mammals: STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6 [1] [3]. While these proteins share a common structural architecture, each member fulfills distinct, non-redundant biological roles, with dysregulation of specific STATs implicated in various human diseases, particularly cancers and autoimmune disorders [2] [3] [4]. This functional specialization, combined with their shared activation mechanism, makes the comparative study of STAT proteins a critical area of research, especially in the development of specific therapeutic inhibitors.

STAT Family Members: Structure, Activation, and Distinct Functions

All seven STAT proteins share a conserved modular structure that facilitates their role in signal transduction and gene activation. This structure consists of six domains: an N-terminal domain (NTD) that mediates protein-protein interactions and dimerization; a coiled-coil domain (CCD) involved in binding other transcription factors and nuclear translocation; a DNA-binding domain (DBD) that recognizes specific DNA sequences; a linker domain (LD) for structural support; a Src homology 2 (SH2) domain that is critical for phosphotyrosine-mediated dimerization; and a C-terminal transactivation domain (TAD) that interacts with transcriptional co-activators [1] [3]. The classical, or "canonical," activation pathway involves extracellular cytokines or growth factors binding to their cognate receptors, which activates associated Janus kinases (JAKs). These JAKs then phosphorylate a specific tyrosine residue on STAT proteins, prompting them to dimerize via reciprocal SH2 domain-phosphotyrosine interactions. The phosphorylated STAT dimers subsequently translocate to the nucleus, bind to specific DNA response elements in target gene promoters, and activate transcription [2] [3].

Despite this common activation mechanism, each STAT family member responds to different extracellular signals and regulates distinct genetic programs, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: The Seven Mammalian STAT Proteins: Activators, Key Functions, and Disease Associations

| STAT Member | Primary Activators | Key Biological Roles | Associated Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAT1 | IFN-α/β, IFN-γ, IL-2 [1] [2] | Antiviral and antibacterial responses, tumor suppression [1] [4] | Immunodeficiency, cancer [2] |

| STAT2 | IFN-α/β [1] [2] | Type I interferon signaling, antiviral defense [1] | Susceptibility to viral infections [2] |

| STAT3 | IL-6 family, EGF, G-CSF [2] [4] | Cell survival, proliferation, differentiation [2] [4] | Cancer, autoimmune diseases [2] [3] [4] |

| STAT4 | IL-12, IL-23 [2] | T-helper 1 (Th1) cell differentiation [2] | Autoimmune disorders [2] |

| STAT5A/B | Prolactin, GH, IL-2, IL-3 [2] | Mammary gland development, lactation, T-cell proliferation (STAT5A); GH signaling, male fertility (STAT5B) [2] [4] | Cancer, immunodeficiency [2] [4] |

| STAT6 | IL-4, IL-13 [2] | T-helper 2 (Th2) cell differentiation, B-cell activation [2] | Allergic asthma, inflammatory diseases [2] |

Beyond the canonical paradigm, growing evidence has revealed "non-canonical" functions for STAT proteins. These include roles in transcriptional repression and activities outside the nucleus, which can involve both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated STATs (uSTATs) [3] [5]. For instance, uSTATs can enter the nucleus and regulate gene expression; uSTAT3 has been shown to bind AT-rich DNA sequences and promote heterochromatin formation, leading to gene silencing [3]. This functional diversity underscores the complexity of STAT biology and the need for member-specific research tools and therapeutics.

Canonical and Non-Canonical STAT Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the canonical activation pathway of STAT proteins and highlights key non-canonical functions, such as nuclear roles for unphosphorylated STATs (uSTATs) and transcriptional repression.

Diagram 1: STAT Protein Signaling Pathways. The diagram shows the canonical activation pathway (dashed box) initiated by cytokine binding, leading to JAK-mediated STAT phosphorylation, dimerization, nuclear import, and target gene activation. This also induces negative feedback regulators like SOCS/PIAS. Non-canonical pathways (green) involve nuclear shuttling of unphosphorylated STATs (uSTATs) leading to gene repression or other functions.

Comparative Screening for STAT-Specific Inhibitors: A Research Focus

The high conservation of the SH2 domain, which is essential for phosphotyrosine binding and STAT dimerization, presents a significant challenge for developing specific inhibitors. Early compound screening efforts that targeted this pocket yielded many small molecules for STAT3, but these often lacked specificity and cross-bound to other STAT family members [6]. This highlighted the inadequacy of existing modeling strategies and underscored the need for comparative screening approaches.

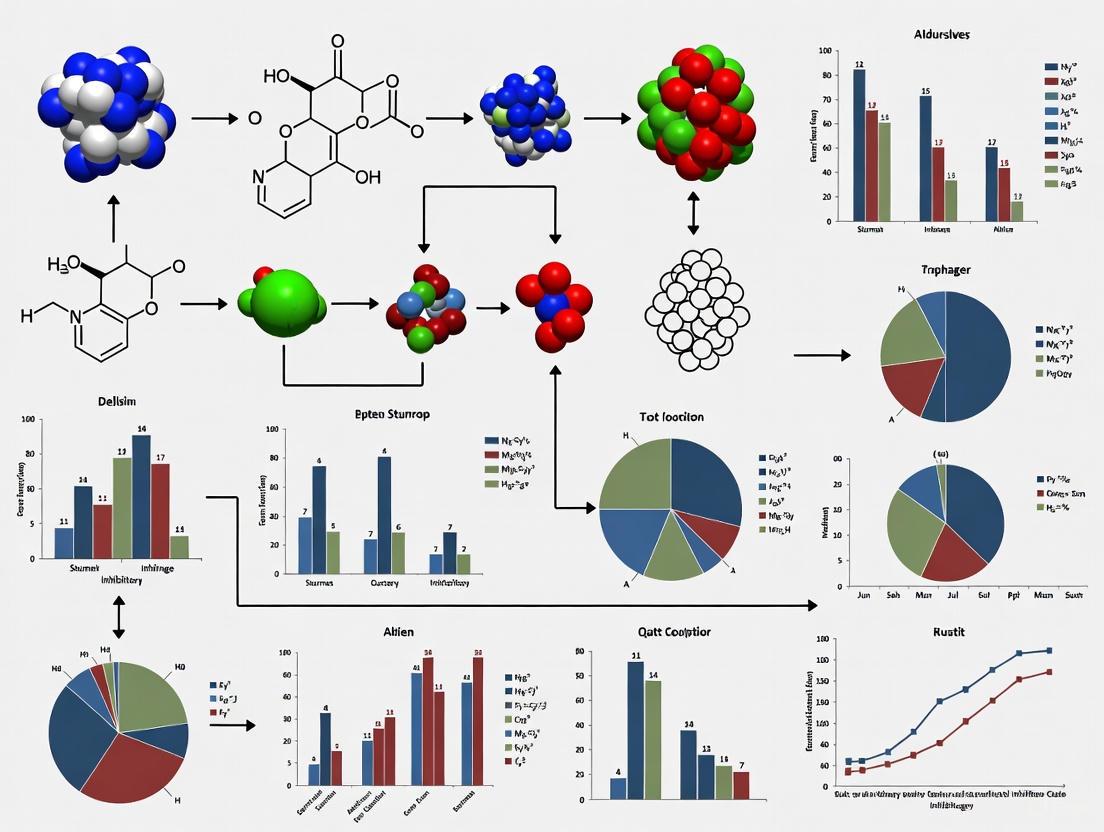

A Novel Virtual Screening and Docking Validation Workflow

To address the specificity challenge, researchers have developed a comparative in silico docking strategy. This workflow involves generating 3D structure models for all human STATs and screening compound libraries against all STATs simultaneously, rather than against a single target like STAT3 [6]. The process can be broken down into the following key stages, which are also depicted in Diagram 2 below:

- Model Preparation: Generating high-quality 3D structural models for the SH2 domains of all seven human STATs.

- Comparative Virtual Screening: Screening large compound libraries (e.g., natural product libraries, multi-million compound clean leads libraries) against the entire STAT family.

- Analysis and Selection: Using two primary selection criteria to identify specific inhibitors:

- The 'STAT-comparative binding affinity value' helps identify compounds with a significantly higher affinity for one STAT over the others.

- The 'ligand binding pose variation' analysis identifies compounds that adopt a different three-dimensional orientation when bound to different STATs, which is crucial for specificity.

- Docking Validation: Rigorously validating the binding mode and affinity of promising compounds through advanced docking simulations [6].

Diagram 2: Workflow for Comparative Virtual Screening of STAT-Specific Inhibitors. This multi-step process emphasizes parallel screening against all STAT family members to identify compounds with high specificity.

This method has provided initial proof for the possibility of identifying STAT1- and STAT3-specific inhibitors from large compound libraries [6]. This tool is crucial for advancing the understanding of the distinct functional roles of STATs in disease and for meeting the clinical need for highly specific, potent, and bioavailable STAT inhibitors.

The Research Toolkit for STAT Inhibitor Screening

The experimental identification and validation of STAT-specific inhibitors rely on a suite of research reagents and methodological approaches. The table below details key resources and their functions in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methods for STAT Inhibitor Studies

| Research Tool | Type | Primary Function in STAT Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant STAT Proteins | Protein Reagent | In vitro binding assays (SPR, ITC), structural studies (X-ray crystallography), and screening for direct inhibitor binding [6]. |

| JAK/STAT-Dependent Cell Lines | Cell Line | Functional validation of inhibitor efficacy, measurement of phospho-STAT levels (via Western blot), and assessment of downstream gene expression changes [2] [4]. |

| Phospho-STAT Specific Antibodies | Antibody | Detect and quantify activated, tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT proteins in cell-based assays (e.g., Western blot, ELISA, flow cytometry) to measure pathway inhibition [4]. |

| STAT Reporter Gene Assays | Cell-Based Assay | Measure STAT-specific transcriptional activity. Cells are engineered with a promoter containing a GAS or ISRE element driving a luciferase reporter [3]. |

| Virtual Screening Compound Libraries | Computational Resource | Large digital collections of small molecules (e.g., natural products, "clean leads") used for in silico docking and initial identification of potential inhibitors [6]. |

The STAT Inhibitor Pipeline and Future Directions

The growing understanding of distinct STAT roles has catalyzed drug development, with over 18 companies and 22 drugs currently in various stages of development [7] [8]. The pipeline reflects a targeted approach, focusing primarily on STAT3 and STAT5 for oncology and STAT1 and STAT6 for inflammatory and autoimmune conditions. Prominent candidates in clinical development include:

- TTI-101 (Tvardi Therapeutics): A small molecule STAT3 inhibitor currently in Phase II clinical trials for breast cancer, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and liver cancer [7] [8].

- KT-621 (Kymera Therapeutics): An oral STAT6 degrader being investigated for the treatment of atopic dermatitis [7] [8].

- VVD-850 (Vividion Therapeutics): A STAT3 inhibitor in Phase I trials for tumors [8].

The future of STAT inhibitor research lies in overcoming the challenge of specificity. The application of comparative screening strategies, combined with a deeper understanding of both canonical and non-canonical STAT functions, will be essential for developing the next generation of precision medicines that can selectively target a single STAT member without disrupting the vital physiological functions of its family counterparts.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a structurally conserved protein module consisting of approximately 100 amino acid residues that plays a fundamental role in intracellular signal transduction by specifically recognizing and binding to phosphorylated tyrosine residues [9] [10]. These domains are contained within the Src oncoprotein and many other intracellular signal-transducing proteins, functioning as critical "readers" of phosphotyrosine-based cellular messages [9] [10]. SH2 domains exhibit a characteristic three-dimensional structure with a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, creating a binding pocket that accommodates phosphotyrosine-containing peptides [10]. The binding mechanism involves a strictly conserved arginine residue that pairs with the negatively charged phosphate group on the phosphotyrosine, along with surrounding pockets that recognize specific flanking sequences on the target peptide, enabling selective protein-protein interactions [10].

SH2 domains are notably absent in yeast and first appear at the evolutionary boundary between protozoa and animalia in organisms such as the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, highlighting their importance in the development of complex multicellular signaling systems [10]. The human genome encodes 120 SH2 domains distributed across 115 distinct proteins, representing a rapid evolutionary expansion that underscores their critical role in eukaryotic biology [9] [10]. These domains are found in diverse protein families including kinases, phosphatases, transcription factors, and adaptor proteins, forming an extensive network that regulates cellular processes ranging from proliferation and differentiation to immune responses and apoptosis [9] [11].

Structural Conservation of SH2 Domains

Conserved Architecture and Binding Mechanism

The structural conservation of SH2 domains across diverse proteins is remarkable. Research analyzing 67 SH2 domain amino acid sequences revealed a conserved pattern of seven core secondary structure regions arranged in a β-α-β-β-β-β-α configuration [12]. This conserved folding pattern creates the binding pocket essential for phosphotyrosine recognition. The most conserved feature is the "two-pronged plug two-hole socket" binding model where the phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) inserts into a highly conserved pocket, while residues C-terminal to the pY, particularly at the pY+3 position, bind to a hydrophobic pocket that provides additional specificity [13].

The extraordinary conservation of the arginine residue responsible for phosphate pairing across all SH2 domains highlights the critical importance of this interaction for domain function [10]. This conservation persists despite the diversity of proteins housing SH2 domains and the various biological processes they regulate. The flanking sequences around this core binding pocket determine specificity for different phosphotyrosine motifs, allowing different SH2 domains to recognize distinct signaling targets while maintaining the same fundamental binding mechanism [10] [13].

Implications for Drug Discovery

The structural conservation of SH2 domains presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic development. The high degree of conservation across the phosphotyrosine binding pocket means that developing selective inhibitors requires careful design to exploit subtle differences in the flanking recognition regions [13] [11]. However, this conservation also means that strategies developed for targeting one SH2 domain may be applicable to others, potentially accelerating the drug discovery process for multiple targets.

The availability of numerous SH2 domain structures has facilitated structure-based drug design approaches, enabling researchers to develop inhibitors with increasing specificity and potency [10] [11]. The conservation pattern also allows for the development of general experimental tools, such as the dipeptide-derived probe used in Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP) that can enrich 22 different SH2 proteins from mixed cell lysates in a single experiment [13].

SH2 Domains as Therapeutic Targets: STAT Proteins

STAT Proteins in Disease and as Therapeutic Targets

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) proteins are both signaling proteins and transcription factors that play critical roles in cell growth, differentiation, and immune function [14]. Among STAT family members, STAT3 and STAT6 have emerged as particularly promising therapeutic targets due to their involvement in various disease processes. STAT3 is implicated in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and immunological and inflammatory responses, with aberrant STAT3 signaling linked to cancer development and progression [15]. STAT6 serves as a key nodal transcription factor that selectively mediates downstream signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, dominant cytokines in the pathophysiology of Type 2 inflammatory diseases such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and chronic spontaneous urticaria [14].

The therapeutic targeting of STAT proteins has gained significant attention because their function depends on SH2 domain-mediated dimerization, which is essential for their nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity [14] [15]. Phosphorylation of a specific tyrosine residue (Tyr705 in STAT3) creates a binding site for the SH2 domain of another STAT molecule, leading to dimerization and subsequent nuclear translocation [16] [15]. Disrupting this SH2 domain-mediated protein-protein interaction presents a promising strategy for inhibiting STAT signaling in disease states.

Current STAT-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches

Table 1: STAT-Targeted Therapeutic Approaches in Development

| Target | Therapeutic Approach | Development Stage | Key Characteristics | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAT6 | REX-8756 (Recludix Pharma) | Preclinical (IND-enabling) | Oral, selective, reversible inhibitor; binds SH2 domain; complete pathway inhibition without protein degradation | Asthma, COPD, atopic dermatitis, other Type 2 inflammatory diseases |

| STAT3 | Small molecule inhibitors (BP-1-102, BTP analogues) | Preclinical/research | Target SH2 domain; disrupt dimerization; show promise against various cancers | Cancer therapy (multiple types) |

| STAT3 | HG110, HG106 (Generative AI-designed) | Preclinical/research | Suppress STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705; inhibit nuclear translocation; identified through deep learning and virtual screening | Non-small cell lung cancer |

Recent advances in STAT6 inhibition include Recludix Pharma's development candidate REX-8756, a potent and selective oral STAT6 inhibitor that targets the SH2 domain [14]. This compound demonstrates complete pathway inhibition in preclinical studies and is well-tolerated, with Investigational New Drug (IND)-enabling activities ongoing to support clinical trials [14]. The approach to STAT6 inhibition is particularly promising because it is downstream in the disease pathway from other drug targets, potentially offering a more selective therapeutic approach with fewer side effects compared to broader inhibitors such as Janus Kinase (JAK) family inhibitors [14].

For STAT3, multiple targeting strategies have emerged, with direct inhibition focusing on three distinct structural regions: the SH2 domain, the DNA binding domain, and the coiled-coil domain [15]. SH2 domain inhibitors have shown particular promise because they prevent the dimerization necessary for STAT3 activation. Recent research has employed innovative approaches such as generative deep learning, virtual screening, and molecular dynamics simulations to identify novel STAT3 inhibitors, with candidates like HG110 demonstrating potent suppression of STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 and inhibition of nuclear translocation in IL-6-stimulated cells [16].

Comparative Screening Methods for STAT-Specific Inhibitors

Experimental Approaches for SH2 Domain Inhibitor Screening

Table 2: Methodologies for Screening SH2 Domain Inhibitors

| Method | Principle | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP) | Immobilized probes capture SH2 proteins from cell lysates | Broad profiling of SH2 domain interactions; evaluation of inhibitor specificity | Can enrich multiple SH2 proteins simultaneously; uses native cellular environment | Limited coverage (22/50 SH2 proteins with current probes) |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Massive libraries of small molecules tagged with DNA barcodes | High-throughput screening against SH2 domains; identification of novel binders | Extremely high diversity (>100 million compounds); efficient screening | Requires specialized technology and selection assays |

| Molecular Docking & Virtual Screening | Computational prediction of compound binding to SH2 domains | Prioritizing candidates for experimental testing; understanding binding modes | Rapid and cost-effective; provides structural insights | Dependent on quality of structural models and scoring functions |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Analysis of temporal evolution of protein-ligand complexes | Assessment of binding stability and interaction profiles | Provides dynamic information beyond static structures | Computationally intensive; requires expertise |

The screening for STAT-specific inhibitors has been revolutionized by advanced technologies that enable comprehensive evaluation of compound efficacy and selectivity. Recludix Pharma has developed a proprietary platform that integrates custom-generated DNA-encoded libraries with massively parallel determination of structure-activity relationships and proprietary screening assays to ensure selectivity [14] [17]. This approach has yielded highly selective SH2 domain inhibitors with exceptional potency (BTK Kd = 0.055 nM) and minimal cytotoxicity (>10,000 nM EC50 in Jurkat cells) [17].

For STAT3 inhibitor identification, researchers have employed generative deep learning models trained on comprehensive datasets of known STAT3 inhibitors to explore chemical space for novel candidates [16]. This computational approach, combined with virtual screening, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations, has accelerated the discovery of promising inhibitors such as HG106 and HG110, which demonstrate superior binding affinities and stable conformations with favorable interactions involving key residues in the STAT3 binding pocket [16].

Figure 1: Workflow for STAT3 Inhibitor Screening and Validation. This diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental approach used to identify and validate STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors, combining virtual screening with biological evaluation.

Selectivity Profiling and Kinome Screening

A critical aspect of developing SH2 domain-targeted therapies is ensuring selectivity to minimize off-target effects. Traditional kinase inhibitors that target the ATP-binding pocket often suffer from limited selectivity due to the conserved nature of kinase domains [17]. In contrast, SH2 domain inhibitors have demonstrated exceptional selectivity profiles. For instance, Recludix's BTK SH2 inhibitor showed >8000-fold selectivity over off-target SH2 domains, significantly exceeding the selectivity of even the most selective kinase domain inhibitors [17].

This enhanced selectivity profile is particularly important for avoiding adverse effects associated with off-target inhibition. For example, traditional BTK inhibitors that target the kinase domain often inhibit TEC kinase, leading to platelet dysfunction and bleeding risks [17]. BTK SH2 domain inhibitors avoid this issue by specifically targeting the SH2 domain without affecting TEC kinase, potentially offering a safer therapeutic profile [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotyrosine Peptide Probes | SH2 domain binding and inhibition studies | IAP experiments; competitive binding assays; specificity profiling | Mimics natural ligands; can be tailored for specificity |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Massive compound screening | SH2 domain inhibitor discovery; structure-activity relationship studies | Extremely high diversity (millions to billions of compounds) |

| SH2-GST Fusion Proteins | Protein interaction studies | Pull-down assays; microarray experiments; interaction mapping | Enables detection with anti-GST antibodies; facilitates purification |

| pY-Peptide Chips | High-throughput interaction profiling | SH2 domain specificity mapping; network analysis | Multiplexed analysis; compatible with fluorescence detection |

| Crystallography Systems | Structural determination | SH2 domain-inhibitor complex analysis; binding mode elucidation | Atomic resolution; detailed interaction information |

The study of SH2 domains and development of targeted inhibitors relies on specialized research tools and methodologies. Affinity-based probes such as the dipeptide-derived probe used in Inhibitor Affinity Purification (IAP) have been designed to contain a phosphotyrosine mimetic and a hydrophobic moiety that addresses the pY+3 binding pocket [13]. These probes enable the enrichment of multiple SH2 domains from complex cell lysates, facilitating proteomic studies of SH2 domain interactions.

Cellular assay systems are crucial for evaluating inhibitor efficacy in biologically relevant contexts. For STAT inhibitors, assays measuring phosphorylation status, nuclear translocation, and downstream gene expression are essential [16] [15]. In preclinical models, compounds are evaluated in disease-relevant systems such as OVA-induced chronic spontaneous urticaria models for BTK inhibitors [17] or IL-6-stimulated cancer cell lines for STAT3 inhibitors [16].

Figure 2: SH2 Domain-Mediated Signaling and Inhibition Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the fundamental process of SH2 domain-dependent signal transduction and the point of intervention for therapeutic inhibitors that prevent SH2 domain recruitment to phosphorylated tyrosine residues.

The strategic targeting of SH2 domains represents a promising frontier in therapeutic development, particularly for STAT proteins involved in cancer and inflammatory diseases. The remarkable structural conservation of SH2 domains across diverse proteins enables researchers to apply similar design principles and screening methodologies to multiple targets, potentially accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutics. The recent success in developing highly selective inhibitors against STAT6 and BTK SH2 domains demonstrates the feasibility of this approach and highlights the potential for improved therapeutic profiles compared to conventional kinase-targeted agents.

Future directions in SH2 domain drug discovery will likely focus on expanding the range of targeted SH2 domains, improving the pharmacological properties of inhibitors, and developing combination therapies that leverage the specificity of SH2 domain targeting. As screening technologies continue to advance, particularly in computational approaches and high-throughput experimental methods, the pace of SH2 domain inhibitor discovery is expected to accelerate. The ongoing clinical development of SH2 domain inhibitors will be crucial for validating this approach and establishing new therapeutic paradigms for diseases driven by aberrant SH2 domain-mediated signaling.

The Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway represents an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of transmembrane signal transduction that enables cells to communicate with their exterior environment [18]. This pathway functions as a fulcrum for numerous cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, metabolism, apoptosis, and immune regulation [2] [19]. More than 50 cytokines, interferons, growth factors, and other specific molecules activate JAK-STAT signaling to drive these physiological and pathological processes [18]. The pathway comprises transmembrane receptors, receptor-associated cytosolic tyrosine kinases (JAKs), and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) [18]. The JAK protein family includes four members: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, while the STAT family consists of seven proteins: STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6 [18] [2].

Upon activation by cytokines or growth factors, JAKs initiate tyrosine phosphorylation of receptors and recruit corresponding STATs [18]. The phosphorylated STATs then dimerize and translocate to the nucleus where they regulate specific gene transcription [2]. This process enables rapid transmission of external signals to the nucleus to regulate biological processes [18]. Dysregulated JAK-STAT signaling and related genetic mutations are strongly associated with immune activation and cancer progression [18] [20]. Insights into the structures and functions of the JAK-STAT pathway have led to the development and approval of diverse drugs for clinical treatment of diseases [18]. Currently, three primary therapeutic strategies target this pathway: cytokine or receptor antibodies, JAK inhibitors, and STAT inhibitors [18]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of STAT-specific inhibitors in development, analyzing their mechanisms, experimental profiles, and potential applications across the therapeutic spectrum.

STAT Protein Family: Structure, Function, and Dysregulation

Structural Composition and Functional Domains

STAT proteins share a conserved multi-domain architecture that enables their function as signal transducers and transcription factors. Structurally, they contain five primary domains: an amino-terminal domain that stabilizes dimers, a coiled-coil domain for protein interactions, a DNA-binding domain that targets specific gene sequences, an SH2 domain crucial for recognizing phosphorylated tyrosines and facilitating dimerization, and a carboxy-terminal transactivation domain [21] [22]. The transactivation domain contains one or two amino acid residues critical for STAT activity; phosphorylation of a particular tyrosine residue promotes dimerization, while phosphorylation of a specific serine residue enhances transcriptional activation [21].

Table 1: STAT Protein Family Members and Their Primary Functions

| STAT Protein | Primary Functions | Key Activators | Role in Disease |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAT1 | Antiviral responses, immune activation | IFNs, ILs | Tumor suppressor; pro-atherogenic |

| STAT2 | Antiviral responses, inflammatory signaling | IFNs | Contributes to carcinogenesis via IL-6 upregulation |

| STAT3 | Cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, immune evasion | IL-6, growth factors | Promotes tumor growth, metastasis; driver in multiple cancers |

| STAT4 | TH1 cell differentiation, inflammatory responses | IL-12 | Associated with autoimmune diseases |

| STAT5A/5B | Mammary gland development, hematopoiesis | Prolactin, GH, cytokines | Promotes tumor growth in hematological and solid malignancies |

| STAT6 | TH2 cell differentiation, allergic responses | IL-4, IL-13 | Regulates allergic inflammation and immune responses |

Mechanisms of Pathway Dysregulation in Disease

Dysregulation of STAT signaling occurs through multiple mechanisms, including aberrant activation by upstream kinases, somatic mutations within STAT genes, and disrupted negative feedback mechanisms [21]. The abnormal activation of STAT proteins is recognized as a cause or driving force behind multiple disease progression pathways [23]. In autoimmune disorders, STAT proteins mediate excessive immune responses, while in cancer, persistently active STATs, particularly STAT3 and STAT5, promote tumorigenesis and progression through dysregulation of critical genes controlling cell growth, survival, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, and metastasis [21]. These genes include p21WAF1/CIP2, cyclin D1, MYC, BCL-X, BCL-2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinases (MMP1, MMP7, MMP9), and survivin [21]. STAT3 also plays a significant role in suppressing tumor immune surveillance, facilitating immune evasion [21].

The following diagram illustrates the core JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its dysregulation in human diseases:

Comparative Analysis of STAT Inhibitors in Development

The therapeutic landscape for STAT inhibitors has expanded significantly, with over 18 companies and 22 drugs in various stages of development as of 2025 [7]. These pipeline products represent diverse mechanistic approaches to targeting STAT proteins, with particular focus on STAT3 and STAT5 due to their established roles in oncogenesis [7] [22]. Emerging opportunities in the STAT inhibitors market lie in targeting dysregulated STAT pathways, particularly STAT3 and STAT5, for cancers and inflammatory conditions [7]. Novel drugs like Tvardi's TTI-101, Kymera's KT-621, and Vividion's VVD-850 highlight advancements in oncology and immunotherapy, capitalizing on potential biomarkers and precision medicine approaches [7].

Table 2: STAT Inhibitors in Clinical Development

| Drug Name | Company | Target | Mechanism | Development Stage | Primary Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTI-101 | Tvardi Therapeutics | STAT3 | Small molecule, SH2 domain inhibitor | Phase II | Breast cancer, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, liver cancer |

| KT-621 | Kymera Therapeutics | STAT6 | Oral STAT6 degrader | Phase I | Atopic dermatitis |

| VVD-850 | Vividion Therapeutics | STAT3 | Small molecule, prevents DNA binding | Phase I | Solid & hematologic tumors |

| Danvatirsen | AstraZeneca | STAT3 | Antisense oligonucleotide | Preclinical/Discovery | Not specified |

| WP1066 | Moleculin | STAT3 | Small molecule inhibitor | Preclinical | Cancer |

| NT-219 | Purple Biotech | STAT3 | Dual inhibitor | Preclinical | Cancer |

Mechanistic Classification of STAT Inhibitors

STAT inhibitory strategies can be broadly categorized into direct and indirect approaches [23]. Direct inhibition focuses on interfering with STAT activation or function through several mechanisms: influencing dimerization by targeting the SH2 domain, preventing DNA binding by targeting the DNA-binding domain, or directly inhibiting phosphorylation by targeting the transactivation domain [23]. Indirect approaches involve inhibiting proteins upstream of STATs, such as JAK kinases (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2) or various interferon and interleukin receptors that mediate STAT activation [23].

The most extensively explored strategy involves preventing STAT dimerization using small molecules identified by in silico 3D modeling and virtual screening of compound libraries [23]. These compounds particularly target the interaction area of the SH2 domain and the phosphorylated tyrosine residue [23]. Among the most potent synthetic small molecules identified through these approaches are STA-21, STATTIC, STX-0119, and OPB-31121 [23]. Other inhibitor classes include natural products (e.g., Resveratrol and its analogs Piceatannol and LYR71, Curcumin), peptides and peptidomimetics (CJ-1383, BP-PM, PM-73), oligodeoxynucleotide decoys, and antisense oligonucleotides [23].

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanistic strategies for targeting STAT proteins:

Experimental Assessment of STAT Inhibitors

Screening Methodologies and Assay Systems

The identification and characterization of STAT inhibitors employs a multidisciplinary experimental approach combining in silico, in vitro, and in vivo methods [23]. The SINBAD (STAT INhibitor Biology And Drug-ability) database represents a curated resource of STAT inhibitors that have been published and scientifically validated, providing crucial experimental details for research design and interpretation [23]. This database includes over 144 inhibitory compounds with detailed experimental characterization, serving as an important tool for comparing inhibitory properties and mechanisms [23].

In silico approaches typically begin with structure-based design, molecular modeling, and virtual screening of compound libraries [23]. These computational methods focus particularly on the SH2 domain and its interaction with phosphorylated tyrosine residues, which is critical for STAT dimerization [23]. Successful hits from virtual screening progress to in vitro validation using techniques including electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) to assess DNA binding capacity, surface plasmon resonance to measure binding kinetics, fluorescence polarization assays, and reporter gene assays using STAT-responsive luciferase constructs [21] [23].

For cellular characterization, researchers employ phospho-STAT immunohistochemistry and Western blotting to assess inhibition of STAT phosphorylation, immunofluorescence to evaluate nuclear translocation, and quantitative PCR to measure expression of STAT target genes [21] [23]. Additional cell-based assays examine functional outcomes including cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle distribution, and invasion capacity [21]. Preclinical in vivo studies utilize xenograft models, genetically engineered mouse models, and disease-specific models (e.g., autoimmune inflammation models) to evaluate efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profiles [21] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for STAT Inhibition Studies

| Reagent/Category | Primary Function | Example Applications | Notable Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH2 Domain Binders | Inhibit STAT dimerization | Block STAT activation and nuclear translocation | TTI-101, STATTIC, STX-0119 |

| DNA Binding Inhibitors | Prevent STAT-DNA interaction | Disrupt transcriptional regulation | VVD-850 |

| PROTAC Degraders | Induce targeted protein degradation | Catalytic degradation of specific STAT proteins | KT-621 (STAT6) |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides | Reduce STAT mRNA levels | Decrease STAT protein expression | Danvatirsen (STAT3) |

| Phospho-STAT Antibodies | Detect activated STATs | Western blot, IHC, flow cytometry | Multiple commercial options |

| STAT-Responsive Reporters | Measure pathway activity | Luciferase-based screening assays | Multiple commercial options |

| JAK Inhibitors | Indirect STAT inhibition | Control experiments, combination studies | Ruxolitinib, Tofacitinib |

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

Oncology Applications

STAT inhibitors show significant promise in oncology, particularly for targeting the well-established roles of STAT3 and STAT5 in promoting tumor growth, survival, and immune evasion [21] [22]. Constitutively active STAT3 is detected in numerous malignancies, including breast, melanoma, prostate, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), multiple myeloma, pancreatic, ovarian, and brain tumors [21]. The genetic and pharmacological modulation of persistently active STAT3 has been shown to control tumor phenotype and lead to tumor regression in vivo [21].

TTI-101, an oral small molecule inhibitor of STAT3, represents one of the most advanced candidates with orphan drug and fast-track designations for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [7] [22]. Its mechanism involves selective binding to the SH2 domain of STAT3, preventing phosphorylation at tyrosine 705 and subsequent dimerization and nuclear translocation [22]. Notably, TTI-101 is designed to inhibit STAT3's canonical nuclear function while preserving its essential non-canonical functions associated with cellular respiration within the mitochondria [22].

Immunological and Inflammatory Applications

In autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, STAT inhibitors offer potential for targeting specific STAT isoforms driving pathological immune responses [18] [20]. KT-621, a first-in-class oral STAT6 degrader from Kymera Therapeutics, demonstrates full inhibition of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in relevant human cell contexts with picomolar potency that was superior to dupilumab in preclinical studies [22]. This STAT6-targeting approach holds particular promise for allergic and atopic conditions such as atopic dermatitis, where the IL-4/IL-13 pathway plays a central role [22].

The therapeutic targeting of STAT pathways in autoimmune diseases must balance efficacy with safety considerations, as different STAT family members have non-redundant biological functions in immune regulation [18]. For instance, while STAT4 inhibition may benefit autoimmune conditions like systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, STAT1 inhibition could potentially increase susceptibility to infections due to its critical role in antiviral defense [21].

The continued development of STAT inhibitors represents a promising frontier in targeted therapy for cancer and autoimmune diseases. Current challenges include achieving sufficient selectivity for individual STAT family members to minimize off-target effects, optimizing pharmacological properties for effective tissue penetration, and identifying predictive biomarkers for patient stratification [21] [23]. Future directions will likely focus on combination strategies integrating STAT inhibitors with other targeted therapies, immunotherapies, or conventional treatments to overcome resistance mechanisms and enhance therapeutic efficacy [21] [24]. Additionally, the exploration of novel modalities such as protein degraders (e.g., KT-621) and allosteric inhibitors (e.g., VVD-850) may expand the therapeutic window and clinical utility of STAT-targeted approaches [7] [22].

As the understanding of STAT biology continues to evolve and more selective inhibitors enter clinical testing, STAT-targeted therapies hold significant potential to address unmet needs across the spectrum of oncological and immunological diseases. The ongoing research efforts and growing pipeline of candidates highlighted in this review underscore the translational momentum in this field and its potential to yield novel therapeutic options for patients with limited alternatives.

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) family of cytoplasmic transcription factors, particularly STAT3 and STAT5, function as critical mediators of oncogenic signaling in diverse malignancies. These proteins are activated by cytokines, growth factors, and various tyrosine kinase receptors, subsequently regulating genes controlling cell cycle progression, apoptosis, survival, and immune responses [25] [26]. In normal physiology, STAT activation is transient and tightly regulated; however, constitutive activation of STAT3 and STAT5 pathways represents a common mechanism driving tumor development, progression, and therapeutic resistance across numerous cancer types [25] [27] [26]. Their role in cancer is complex and context-dependent, as they can function as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors depending on cellular environment and tumor type [25]. The development of STAT-specific inhibitors represents an emerging frontier in targeted cancer therapy, particularly for malignancies resistant to conventional treatments.

Comparative Molecular Pathology of STAT3 and STAT5

Activation Mechanisms and Oncogenic Signaling

STAT3 and STAT5 share structural similarities with six conserved domains, yet they exert distinct and overlapping functions in cancer pathogenesis. Both proteins are phosphorylated by upstream kinases (particularly JAK family members), form dimers, and translocate to the nucleus to regulate transcription of target genes [25] [26]. However, they display different expression patterns and context-dependent functions: STAT5a is predominantly expressed in mammary tissue, while STAT5b is more enriched in muscle and liver [28]. Despite 94% amino acid sequence identity, STAT5a and STAT5b exert nonredundant functions with unique target gene activation patterns [28].

The oncogenic activities of STAT3 and STAT5 include regulation of genes controlling cell cycle (Cyclin D1, c-Myc), apoptosis (Bcl-xL, Bcl-2, Mcl-1), and angiogenesis (HIF1α, VEGF) [26]. Recent advances also highlight their critical roles in mediating inflammation, stemness, and mitochondrial functions essential for cellular transformation [25]. STAT3 mitochondrial functions are particularly required for transformation, while both STAT3 and STAT5 regulate metabolic pathways that support tumor survival under stress conditions [25].

Mutation Profiles and Activation Frequency in Human Cancers

The mutation landscape and activation patterns of STAT3 and STAT5 differ significantly across cancer types:

STAT3 and STAT5 Mutation Profile in Solid Cancers (Figure 1)

Figure 1: STAT3/5 Mutation Landscape in Human Cancers

Unlike hematological malignancies where STAT mutations are more common, STAT3/5 mutations in solid cancers are relatively infrequent, with STAT3 mutations being more prevalent than STAT5A or STAT5B mutations [25]. Gastrointestinal cancers demonstrate the highest rates of STAT3/5 mutations compared with other solid cancers [25]. Missense mutations tend to cluster within the SH2 domain, where gain-of-function mutations were previously characterized, as well as within the DNA binding domain [25]. The STAT3 Y640F hotspot gain-of-function mutation reported in lymphoid malignancies has also been detected in liver cancer patients, while a hotspot frameshift mutation at position Q368 within the DNA binding domain of STAT5B has been reported in 24 patients with various carcinomas [25].

Despite relatively low mutation rates, STAT3/5 activation is very frequent in human cancers, likely reflecting increased cytokine signaling or mutations in negative regulators [25]. A recent meta-analysis of 63 studies concluded that STAT3 protein overexpression was significantly associated with worse 3-year and 5-year overall survival in patients with solid tumors, though interestingly, high STAT3 expression predicted better prognosis for breast cancer [25].

Table 1: Association of STAT3/5 Activation with Patient Survival in Major Cancers

| Tumor Type | Biomarker | Overall Survival Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-small Cell Lung Cancer | High p-STAT3 | HR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.04–1.46, p = 0.02 | [25] |

| Liver Cancer (HCC) | High p-STAT3 | HR 1.69, 95% CI: 1.07–2.31, p < 0.0001 (3yr) | [25] |

| Glioblastoma Multiforme | High p-S727-STAT3 | HR 1.797, 95% CI: 1.028–3.142, p = 0.040 | [25] |

| Renal Cell Carcinoma | High p-S727-STAT3 | HR 3.32, 95% CI: 1.26–8.71, p = 0.014 (10yr) | [25] |

| Breast Cancer | Low p-STAT5 | HR 2.49, 95% CI: 1.23–5.05, p = 0.012 (5yr) | [25] |

| Prostate Cancer | High nuclear STAT5A/B | HR 1.59, 95% CI: 1.04–2.44, p = 0.034 | [25] |

| Colon Cancer | High p-STAT3/p-STAT5 ratio | HR 4.468, p = 0.043 (5yr) | [25] |

Mechanisms of Therapy Resistance

STAT3-Mediated Resistance Pathways

STAT3 activation contributes to therapy resistance through multiple mechanisms across different cancer types. In melanoma, STAT3 confers resistance to anoikis (anchorage-independent cell death), enabling metastatic dissemination [29]. When cultured under anchorage-independent conditions, approximately 65-75% of melanoma cells resist anoikis, with these resistant cells demonstrating significantly higher expression and phosphorylation of STAT3 at Y705 compared to adherent cells [29]. This STAT3-mediated anoikis resistance directly enhanced metastatic potential, as STAT3 knock-down cells failed to metastasize in SCID-NSG mice compared to untreated anchorage-independent cells, which formed large tumors and extensively metastasized [29].

In targeted therapy resistance, STAT3 activation serves as a crucial mechanism of resistance in BRAFV600E-mutant melanoma treated with vemurafenib [30]. Vemurafenib-resistant melanoma remodels into an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by increasing chemokine expression to facilitate infiltration of immunosuppressive immune cells, particularly myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [30]. This resistance mechanism can be overcome by STAT3 inhibition, which reduces MDSCs and TAMs while increasing infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment [30].

STAT5-Mediated Resistance Pathways

STAT5 activation drives therapy resistance through distinct mechanisms, particularly in hematopoietic malignancies and breast cancer. In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), STAT5 contributes to resistance against BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) through survival pathway activation that persists despite BCR-ABL1 inhibition [31]. Combined targeting of STAT3 and STAT5 has demonstrated efficacy in overcoming this resistance, particularly for highly resistant sub-clones expressing BCR-ABL1T315I or T315I-compound mutations [31].

In breast cancer, STAT5a confers doxorubicin resistance by directly regulating ABCB1 transcription, encoding a membrane transporter that promotes chemoresistance by exporting antitumor drugs from cancer cells [28]. Doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cell lines (MCF7/DOX) and chemoresistant patients show significantly higher expression of both STAT5a and ABCB1, with their expression levels positively correlated [28]. Targeting STAT5a with pimozide, an FDA-approved psychotropic drug, significantly sensitized breast cancer cells to doxorubicin both in vitro and in vivo [28].

Table 2: STAT3 vs. STAT5 Mechanisms in Therapy Resistance

| Resistance Mechanism | STAT3 | STAT5 |

|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy Resistance | Regulation of survival genes (Bcl-2, Mcl-1) | Upregulation of drug efflux transporters (ABCB1) |

| Targeted Therapy Resistance | Microenvironment remodeling immunosuppression | Bypass signaling pathway activation |

| Immunotherapy Resistance | Increased MDSCs and TAMs infiltration | Not well characterized |

| Metastatic Resistance | Anoikis resistance through mitochondrial functions | Limited evidence |

| Stem Cell Maintenance | Cancer stem cell population maintenance | Leukemic stem cell survival |

STAT3/STAT5 Balance in Tumor Immunity

Recent research has revealed that the balance between STAT5 and STAT3 transcriptional pathways in dendritic cells (DCs) critically shapes antitumor immunity and determines responses to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) [32]. Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis of tumor tissues from patients receiving ICB demonstrated that patients classified as DC1hiSTAT5/STAT3hi had the longest overall survival, while DC1lowSTAT5/STAT3low patients had the shortest survival [32]. ICB treatment dynamically reprograms the STAT5 and STAT3 transcriptional pathways in conventional DCs (cDCs), with responders showing increased STAT5 signaling and decreased STAT3 signaling following treatment, changes not observed in non-responders [32].

Mechanistically, STAT3 restrains the JAK2 and STAT5 transcriptional pathway, thereby determining DC fate and function [32]. Genetic deletion and pharmacologic inhibition of STAT3 signaling led to DC1 activation and profound anti-tumor T cell immune responses. The development of STAT3 degraders (SD-36 and SD-2301) effectively reprogrammed the DC transcriptional network toward immunogenicity, demonstrating efficacy as monotherapy for advanced and ICB-resistant tumors without toxicity in mouse models [32].

Figure 2: STAT3/STAT5 Balance in Immunotherapy Response

Experimental Models and Methodologies

Key Experimental Protocols for STAT Inhibition Studies

Combination Therapy in Vemurafenib-Resistant Melanoma: The efficacy of combining STAT3 inhibition with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy was evaluated using APTSTAT3-9R, a cell-permeable STAT3 inhibitory peptide [30]. Intratumoral treatment with APTSTAT3-9R reduced populations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) while increasing infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment [30]. Combination therapy with APTSTAT3-9R and anti-PD-1 antibody significantly suppressed tumor growth by decreasing immunosuppressive immune cells while increasing infiltration and cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells [30].

Dual STAT3/STAT5 Inhibition in T-Prolymphocytic Leukemia: Researchers evaluated JPX-1244, a dual STAT3/STAT5 non-PROTAC degrader, in primary T-PLL samples, including those resistant to conventional therapies [33]. The compound efficiently induced cell death by blocking STAT3 and STAT5 phosphorylation and inducing their degradation, with the extent of STAT3/STAT5 degradation directly correlating with cytotoxicity [33]. RNA-sequencing confirmed treatment-related downregulation of STAT5 target genes. Combination screening identified cladribine, venetoclax, and azacytidine as effective combination partners that synergistically reduced STAT5 phosphorylation even in low-responding T-PLL samples [33].

Anoikis Resistance Assay in Melanoma: The role of STAT3 in anoikis resistance was evaluated by culturing melanoma cell lines (SK-MEL-28, SK-MEL-2, SK-MEL-5, MeWo, and B16-F0) under low attachment conditions in plates coated with poly-HEMA for 48 hours [29]. Cell viability was assessed using Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay and compared to cells under adherent conditions. STAT3 inhibitors (AG 490 and piplartine) induced anoikis in a concentration-dependent manner in resistant cells, while STAT3 overexpression or IL-6 treatment increased anoikis resistance [29]. Metastatic potential was evaluated using wound healing, Boyden's chamber invasion assays, and in vivo models in SCID-NSG mice [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for STAT Pathway Investigation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAT3 Inhibitors | AG 490, Piplartine (PL), Stattic, LLL-3, LLL12, SD-36, SD-2301, APTSTAT3-9R | Mechanistic studies of STAT3 function; combination therapies | Varying selectivity profiles; APTSTAT3-9R is cell-permeable peptide [29] [26] [32] |

| Dual STAT3/5 Inhibitors | JPX-1244, CDDO-Me (bardoxolone methyl) | Targeting compensatory signaling; resistant malignancies | CDDO-Me also modulates Nrf2 pathway and induces HO-1 [33] [31] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | p-STAT3 (Y705, S727), p-STAT5 (Y694/699) | Assessment of pathway activation; patient stratification | Critical for correlating activation with clinical outcomes [25] [28] |

| Gene Manipulation Tools | shRNA/siRNA (Stat3, Stat5a, Stat5b), Overexpression vectors | Functional validation of targets; mechanistic studies | STAT3 knock-down reduces metastatic potential in vivo [32] [29] |

| Cell Line Models | MCF7/DOX (doxorubicin-resistant), T-PLL primary cells, BCR-ABL1+ lines | Therapy resistance studies; drug screening | Primary cells essential for translational relevance [28] [33] [31] |

| Animal Models | SCID-NSG mice, Stat3fl/flXcr1cre mice | Metastasis studies; immunotherapy response evaluation | cDC1-specific STAT3 knockout reveals immune functions [32] [29] |

Emerging Therapeutic Landscape and Clinical Outlook

The STAT inhibitor pipeline has expanded significantly, with over 18 companies and 22 drugs in various stages of development as of 2025 [7]. Emerging candidates include Tvardi's TTI-101 (a small molecule STAT3 inhibitor in Phase II trials for breast cancer, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and liver cancer), Kymera's KT-621 (an oral STAT6 degrader for atopic dermatitis), and Vividion's VVD-850 (focusing on STAT3 inhibition for tumors) [7]. Clinical development has been challenged by the need to achieve therapeutic efficacy without disrupting essential STAT functions in normal physiology, though the observation that cancer cells are more dependent on STAT activity than their normal counterparts provides a therapeutic window [26].

Future directions in STAT-targeted therapy will likely focus on several key areas: First, combination strategies simultaneously targeting STAT3 and STAT5 may overcome compensatory signaling that limits single-agent efficacy [33] [31]. Second, the development of degraders (PROTACs) rather than mere inhibitors offers more complete pathway suppression [32] [33]. Third, biomarker-driven patient selection based on STAT activation status or STAT5/STAT3 balance may identify populations most likely to respond [25] [32]. Finally, rational combinations with immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted agents may leverage STAT inhibition to overcome multiple resistance mechanisms [30] [31].

The complex biology of STAT3 and STAT5 continues to present both challenges and opportunities for cancer therapy. Their context-dependent roles as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors necessitate careful therapeutic modulation rather than complete inhibition. However, the accumulating evidence of their central role in therapy resistance across diverse malignancies underscores the urgent need to advance STAT-targeted strategies into clinical application.

The Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) protein family comprises seven structurally and functionally related members: STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT4, STAT5A, STAT5B, and STAT6 [23] [21]. These proteins function as critical cytoplasmic transcription factors that mediate cellular responses to cytokines, growth factors, and pathogens [34] [21]. Upon activation, STAT proteins dimerize through reciprocal phosphotyrosine-SH2 domain interactions, translocate to the nucleus, and bind specific DNA response elements to regulate gene transcription [23] [21]. This signaling pathway controls fundamental cellular processes, including cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, immune responses, and inflammation [21].

Abnormal activation of STAT signaling pathways is implicated in numerous human diseases [35] [21]. Notably, constitutively active STAT3 is detected in a wide array of malignancies, including breast, melanoma, prostate, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, and pancreatic cancers [21]. STAT3 and STAT5 hyperactivation promotes tumorigenesis through dysregulation of genes controlling cell survival, proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis [36] [22]. Beyond oncology, STAT protein dysregulation contributes to autoimmune diseases, inflammatory disorders, and viral infections [23] [21]. This established STAT proteins, particularly STAT3 and STAT5, as attractive therapeutic targets for drug development.

Current STAT Inhibitor Clinical Pipeline

The STAT inhibitor pipeline has expanded significantly, with over 18 companies developing 22+ pipeline drugs across clinical stages from discovery to Phase III trials [36] [22]. The following table summarizes prominent STAT inhibitors currently in development:

Table 1: Selected STAT Inhibitors in Clinical Development

| Drug/Candidate | Company | Target | Development Stage | Key Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTI-101 | Tvardi Therapeutics | STAT3 | Phase II | Breast Cancer, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, Liver Cancer [36] [22] |

| KT-621 | Kymera Therapeutics | STAT6 | Phase I | Atopic Dermatitis [36] [22] |

| VVD-850 | Vividion Therapeutics | STAT3 | Phase I | Solid & Hematologic Tumors [36] [22] |

| BAY 3630914 | Bayer | STAT3 | Research/Preclinical | Not Specified [22] |

| WP1066 | Moleculin | STAT3 | Research/Preclinical | Not Specified [22] |

| NT-219 | Purple Biotech | STAT3 | Research/Preclinical | Not Specified [22] |

| Danvatirsen | AstraZeneca | STAT3 | Research/Preclinical | Not Specified [22] |

The pipeline showcases diverse therapeutic approaches, including small molecules, peptide-based inhibitors, and oligonucleotide decoys [22] [21]. Tvardi Therapeutics' TTI-101 represents one of the most advanced candidates, having received FDA orphan drug designation for both idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as Fast-Track Designation for hepatocellular carcinoma [22]. The drug is an oral small molecule inhibitor that binds the SH2 domain of STAT3, preventing its phosphorylation, dimerization, and nuclear translocation while preserving mitochondrial functions [22].

The pipeline remains predominantly early-stage, with the majority of candidates in preclinical through Phase II development [36] [37]. Notably, as of 2025, only one STAT3-targeting medication (Golotimod) has gained approval, with restricted accessibility and application [37]. This highlights the significant unmet medical need and market opportunity for effective STAT inhibitors across multiple disease domains.

STAT Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

STAT Activation and Inhibition Pathway

The canonical STAT signaling pathway involves multiple sequential steps that can be targeted therapeutically. The following diagram illustrates key activation and inhibition mechanisms:

Diagram 1: STAT activation and therapeutic inhibition. STAT inhibitors primarily target the SH2 domain to prevent dimerization, while indirect approaches include upstream JAK inhibition or DNA-binding competition with decoy oligonucleotides [23] [21].

Comparative Screening Workflow for STAT Inhibitors

The development of STAT-specific inhibitors faces challenges due to the high conservation of the SH2 domain across STAT family members [35] [34]. To address this, researchers have developed sophisticated comparative screening approaches:

Diagram 2: Comparative screening workflow for specific STAT inhibitors. This pipeline approach addresses cross-binding specificity challenges posed by the conserved SH2 domain through comparative virtual screening and validation [35] [34] [38].

The comparative binding affinity value (STAT-CBAV) and ligand binding pose variation (LBPV) parameters serve as key selection criteria for identifying STAT-specific inhibitors during virtual screening [34]. This methodology represents a significant advancement over earlier approaches that often yielded compounds with insufficient specificity due to high structural conservation among STAT family members [35].

Experimental Platforms and Research Toolkit

Key Methodologies in STAT Inhibitor Development

STAT inhibitor research employs diverse experimental methodologies spanning computational, biochemical, and biological systems:

Table 2: Essential Experimental Methods for STAT Inhibitor Development

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Application in STAT Research | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Screening | Comparative Virtual Screening [34] [38], Molecular Docking [39], Molecular Dynamics Simulations [39] | Identification of specific STAT inhibitors from compound libraries, Binding affinity and pose validation [34] [38] | STAT-CBAV calculation, Binding pose stability assessment [34] |

| Cellular Assays | STAT Phosphorylation Assays [35], Luciferase Reporter Gene Assays [39], Cellular Thermal Shift Assays [39], Cytotoxicity/Cell Proliferation Assays [39] | Validation of STAT inhibition in cellular contexts, Assessment of functional effects on signaling [35] [39] | IC50 determination, Pathway inhibition confirmation, Antiproliferative effects [39] |

| In Vivo Models | Xenograft Tumor Models [21], Disease-Specific Animal Models (e.g., inflammation, autoimmunity) [21] | Evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and toxicity in physiological systems [21] | Tumor growth inhibition, Disease pathology modification, Toxicity profiles [21] |

Research Reagent Solutions for STAT Investigations

The following toolkit outlines essential reagents and resources for conducting STAT inhibitor research:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for STAT Inhibitor Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| STAT Structural Databases | Provides 3D protein models for virtual screening | SINBAD (STAT INhibitor Biology And Drug-ability) database [23] |

| Compound Libraries | Source of potential inhibitor candidates for screening | Natural product libraries, Clean leads (CL) libraries, Commercial small molecule databases [34] [39] |

| Validated Reference Inhibitors | Positive controls for experimental validation | Stattic, S3I-201, STA-21 (known STAT3 inhibitors) [34] [39] |

| Cell Line Panels | Disease-relevant models for functional testing | Gastric cancer lines (MGC803, KATO III, NCI-N87), Breast cancer lines, Other STAT-dependent malignancies [39] |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Detection of STAT activation states | Anti-pY-STAT3, Anti-pY-STAT1, Anti-pY-STAT5 [35] [23] |

The STAT inhibitor field continues to evolve with several promising directions emerging. Structure-based drug design leveraging comprehensive databases like SINBAD provides refined starting points for candidate optimization [23]. Advanced delivery systems, including nanoparticle-based carriers and siRNA approaches, may overcome limitations of bioavailability and cellular uptake that have plagued earlier candidates [37]. Additionally, the therapeutic potential of STAT inhibitors continues to expand beyond oncology to include autoimmune diseases, inflammatory conditions, and viral infections [23] [37].

The increasing understanding of STAT biology and improvements in specificity profiling through comparative screening approaches position the field to potentially deliver transformative therapies for diseases with significant unmet needs. As candidates advance through clinical development, the coming years will be pivotal in realizing the clinical potential of STAT-targeted therapeutics.

Screening Methodologies for STAT Inhibitor Discovery: From Traditional to AI-Driven Approaches

Virtual Screening and Comparative In Silico Docking Strategies

Virtual screening has become an indispensable tool in computational drug discovery, enabling researchers to prioritize candidate molecules from vast chemical libraries for experimental testing. Within structure-based drug design, molecular docking serves as a cornerstone technique for predicting how small molecules interact with biological targets at the atomic level. As the field progresses, multiple docking strategies have emerged, including traditional physics-based approaches, pharmacophore-based methods, and increasingly sophisticated deep learning algorithms. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these virtual screening methodologies, with particular emphasis on their application in identifying STAT-specific inhibitors—a promising therapeutic avenue for cancer and inflammatory diseases. We objectively evaluate the performance of various docking programs through experimental data and enrichment metrics, providing researchers with practical insights for selecting appropriate strategies for their specific drug discovery campaigns.

Virtual Screening Methodologies: A Comparative Framework

Virtual screening approaches can be broadly categorized into several paradigms, each with distinct theoretical foundations and implementation strategies.

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) relies on known active compounds to identify new candidates with similar structural or physicochemical properties. The BIOPTIC B1 system exemplifies a modern LBVS approach, utilizing a SMILES-based transformer model pre-trained on ~160 million molecules and fine-tuned on BindingDB data to learn potency-aware embeddings. This system maps each molecule to a 60-dimensional vector and performs ultra-high-throughput screening using SIMD-optimized cosine search over pre-indexed libraries, enabling the evaluation of 40 billion compounds in just weeks rather than years [40].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) utilizes the three-dimensional structure of the target protein to identify potential binders. Molecular docking, a primary SBVS technique, aims to predict the native binding pose of a ligand within a protein's binding site and estimate the binding affinity through scoring functions [41]. Docking programs typically consist of two components: a search algorithm that explores possible ligand conformations and orientations, and a scoring function that evaluates the binding affinity of each pose [42].

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS) represents an intermediate approach that identifies essential interaction features between a ligand and its target without requiring precise atomic coordinates. A pharmacophore model captures the spatial arrangement of features such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups that are critical for biological activity [43].

Table 1: Classification of Virtual Screening Approaches

| Methodology | Requirements | Key Advantages | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based (LBVS) | Known active compounds | High throughput, no protein structure needed | BIOPTIC B1, similarity search |

| Structure-Based (SBVS) | 3D protein structure | Direct modeling of binding interactions | Glide, GOLD, AutoDock Vina |

| Pharmacophore-Based (PBVS) | Ligand-protein interaction features | Balanced accuracy and speed | Catalyst, LigandScout |

| Deep Learning Docking | Training datasets on complexes | Pattern recognition from large datasets | SurfDock, DiffBindFR, DynamicBind |

Performance Benchmarking of Docking Strategies

Traditional vs. Deep Learning Docking Performance

Recent comprehensive evaluations have revealed distinct performance patterns across docking methodologies. A 2025 benchmark study assessed multiple docking approaches across three datasets: the Astex diverse set (known complexes), PoseBusters benchmark set (unseen complexes), and DockGen dataset (novel protein binding pockets). The results demonstrated a clear performance hierarchy, enabling classification into four tiers based on combined success rates (RMSD ≤ 2 Å & physically valid poses): traditional methods > hybrid AI scoring with traditional conformational search > generative diffusion methods > regression-based methods [42].

Generative diffusion models such as SurfDock exhibited exceptional pose accuracy, achieving RMSD ≤ 2 Å success rates exceeding 70% across all datasets (91.76% on Astex, 77.34% on PoseBusters, and 75.66% on DockGen). However, these models showed deficiencies in producing physically valid poses, with PB-valid scores of 63.53%, 45.79%, and 40.21% respectively, resulting in moderate combined success rates. Traditional methods like Glide SP consistently excelled in physical validity, maintaining PB-valid rates above 94% across all datasets, though with somewhat lower pose accuracy than the best diffusion models [42].

Table 2: Docking Performance Across Methodologies (Success Rates %)

| Method Category | Representative Program | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid) | Combined Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Glide SP | 75.30% (Astex) | 97.65% (Astex) | 73.42% (Astex) |

| Generative Diffusion | SurfDock | 91.76% (Astex) | 63.53% (Astex) | 61.18% (Astex) |

| Regression-Based | KarmaDock | 42.35% (Astex) | 28.24% (Astex) | 15.29% (Astex) |

| Hybrid AI | Interformer | 68.82% (Astex) | 81.18% (Astex) | 58.82% (Astex) |

Pharmacophore vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening

A landmark study comparing pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) across eight structurally diverse protein targets revealed surprising performance differences. Using Catalyst for PBVS and three docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, Glide) for DBVS, researchers found that in fourteen of sixteen virtual screening sets, PBVS demonstrated higher enrichment factors than DBVS. The average hit rates over the eight targets at 2% and 5% of the highest database ranks were substantially higher for PBVS than for DBVS, establishing PBVS as a powerful method for retrieving active compounds from databases [43].

Multi-Program Benchmarking Using DUD-E

A comprehensive benchmark of four popular docking programs (Gold, Glide, Surflex, and FlexX) using the DUD-E database (containing 102 targets with 22,886 actives and 1.4 million decoys) provided insights into relative performance across diverse protein families. Evaluation using BEDROC scores with α = 80.5 (where 2% top-ranked molecules account for 80% of the score) showed that Glide succeeded (score > 0.5) for 30 targets, Gold for 27, FlexX for 14, and Surflex for 11. Performance variation depended on the early recognition metric, with Glide showing particular strength for early recognition problems (α = 321.9, corresponding to top 0.5% of compounds) [44].

However, this study also highlighted a critical methodological consideration: when all targets with potential biases were removed, leaving a subset of 47 targets, performance dropped dramatically for all programs (Glide succeeded for only 5 targets, Gold for 4, FlexX and Surflex for 2). This underscores the importance of bias-aware benchmark interpretation and the value of using multiple programs combined in virtual screening campaigns [44].

Experimental Protocols for Virtual Screening

Standard Virtual Screening Workflow

A robust virtual screening protocol typically follows a multi-stage process to maximize the identification of true active compounds while maintaining computational efficiency:

1. Target Preparation: Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from experimental sources (X-ray crystallography, NMR, cryo-EM) or homology modeling. For STAT-specific inhibitor research, this would involve preparing the STAT protein structure, particularly focusing on the SH2 domain critical for dimerization and activation. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligands except those critical for structural integrity or binding. Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and define protonation states of residues using tools like MolProbity or PROCHECK.

2. Binding Site Identification: Precisely define the binding pocket coordinates. For novel targets, use pocket detection algorithms like FPocket, DeepSite, or metaPocket. For STAT proteins, the phosphotyrosine binding pocket within the SH2 domain represents the primary target for inhibitor development.

3. Library Preparation: Curate compound libraries by converting 2D structures to 3D conformations using tools like OMEGA or Corina. Apply appropriate protonation states at physiological pH (typically 7.4) and generate multiple tautomers and stereoisomers where relevant. Filter compounds using drug-likeness criteria (Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's rules) and remove compounds with undesirable functional groups using PAINS filters.

4. Molecular Docking: Execute docking simulations using selected programs with validated parameters. For STAT inhibitors, employ a balanced approach with both traditional (Glide, GOLD) and deep learning methods (SurfDock) to leverage complementary strengths. Use consensus docking where computationally feasible.

5. Pose Analysis and Selection: Cluster resulting poses based on binding modes and interactions. Prioritize compounds that form key interactions with STAT residues known to be critical for function (e.g., residues involved in phosphopeptide binding). Use molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) calculations to refine binding affinity predictions for top candidates.

6. Experimental Validation: Synthesize or procure top-ranking compounds and evaluate their activity using biochemical assays (e.g., fluorescence polarization, surface plasmon resonance) and functional assays in cellular models of STAT signaling.

Assessment Metrics for Virtual Screening Performance

Proper evaluation of virtual screening performance requires multiple complementary metrics that address different aspects of method effectiveness:

Enrichment Factor (EF) measures the concentration of active compounds at the top of a ranked list compared to random selection. The traditional EF formula is defined as:

[ EF{\chi} = \frac{(N{actives}^{selected}/N{total}^{selected})}{(N{actives}^{total}/N_{total}^{total})} ]

where χ represents the selection fraction (e.g., 1%, 5%) [44]. However, this metric has limitations, particularly its dependence on the ratio of actives to decoys in the benchmark set, which constrains its maximum achievable value [45].

Bayes Enrichment Factor (EFB) represents an improved metric that addresses limitations of traditional EF:

[ EF{\chi}^{B} = \frac{\text{Fraction of actives whose score is above } S{\chi}}{\text{Fraction of random molecules whose score is above } S_{\chi}} ]

where (S{\chi}) is the cutoff score such that (P(S > S{\chi}) = \chi). This approach requires only random compounds rather than carefully curated decoys and has no dependence on the ratio of actives to random compounds in the set, avoiding the ceiling effect of traditional EF [45].

BEDROC (Boltzmann-Enhanced Discrimination of ROC) incorporates an exponential weighting scheme that emphasizes early recognition, addressing the fact that virtual screening primarily concerns early enrichment rather than overall classification performance. The BEDROC formula is:

[ BEDROC = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} e^{-\alpha ri/N}}{Ra \left( \frac{1 - e^{-\alpha}}{e^{\alpha/N} - 1} \right)} \times \frac{Ra \sinh(\alpha/2)}{\cosh(\alpha/2) - \cosh(\alpha/2 - \alpha Ra)} + \frac{1}{1 - e^{\alpha(1 - Ra)}} ]

where (n) is the number of actives, (N) the total compounds, (Ra) the ratio of actives, (ri) the rank of the ith active, and (\alpha) a parameter controlling early recognition emphasis [44].

Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) measures pose prediction accuracy by calculating the deviation between predicted and experimentally determined ligand binding poses, with RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å typically considered successful prediction [42].

Physical Validity Rate assesses the chemical and geometric plausibility of predicted poses using tools like PoseBusters, which check bond lengths, angles, stereochemistry, and protein-ligand clashes [42].

Application to STAT-Specific Inhibitor Research

Special Considerations for STAT Protein Targets

STAT proteins present unique challenges for virtual screening due to their flexible domains, extensive protein-protein interaction surfaces, and shallow binding pockets. Successful virtual screening campaigns for STAT inhibitors should incorporate several specialized strategies:

SH2 Domain Focus: The Src homology 2 (SH2) domain represents the most targeted region for STAT inhibition, as it mediates critical phosphotyrosine-dependent dimerization. Docking protocols should prioritize compounds that mimic phosphotyrosine interactions while overcoming the challenges of targeting phosphate-binding sites.

Allosteric Site Exploration: Beyond the SH2 domain, explore allosteric sites that might modulate STAT function with alternative mechanisms. These include the coiled-coil domain, DNA-binding domain, and N-terminal domain, which offer potential for more selective inhibition.