Centrifugation and Ultracentrifugation: A Comprehensive Guide for Cell Component Separation in Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to centrifugation and ultracentrifugation for isolating cell components.

Centrifugation and Ultracentrifugation: A Comprehensive Guide for Cell Component Separation in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a complete guide to centrifugation and ultracentrifugation for isolating cell components. It covers the fundamental principles of separation by density and size, details specific methodologies for applications from protein purification to exosome isolation, and offers practical troubleshooting advice for common issues. The content also explores the validation of separation efficacy and compares advanced, high-throughput technologies, equipping readers with the knowledge to optimize their protocols for downstream analytical and therapeutic applications in fields like biopharmaceuticals and personalized medicine.

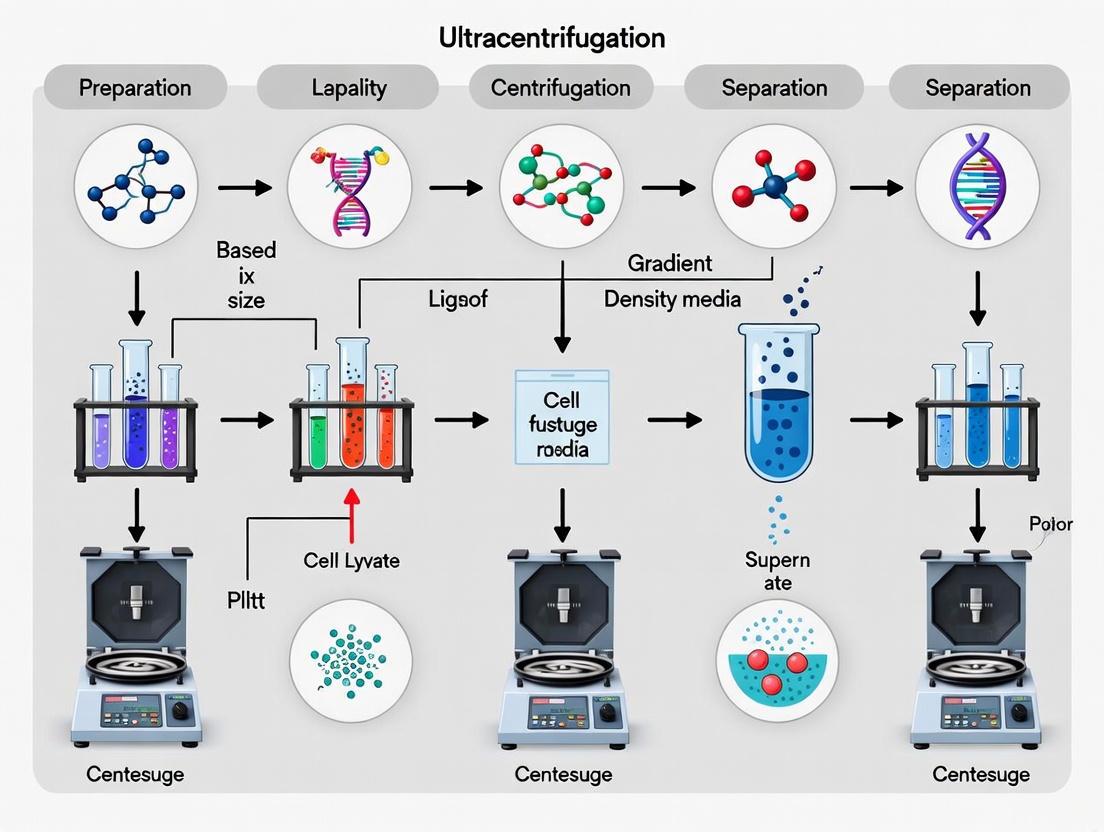

Core Principles: How Centrifugation Separates Cell Components by Density and Size

Centrifugation is a foundational mechanical technique used for separating particles from a solution based on their size, shape, density, the viscosity of the medium, and the rotor speed [1] [2]. In practice, a sample suspended in a liquid medium is placed in a tube within a centrifuge rotor. As the rotor spins at high speed, it generates a centrifugal force that acts perpendicular to the axis of rotation, causing denser particles to move radially away from the center while less dense components migrate towards the center [1] [2]. This process dramatically accelerates the natural sedimentation that would occur under Earth's gravity, reducing separation times from hours or days to minutes [3]. The technique is indispensable across numerous scientific fields, including biochemistry, cell biology, pharmaceutical development, and environmental engineering [1] [3].

The effectiveness of centrifugation is governed by several key principles and forces. The Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF), measured in multiples of gravitational force (×g), is the driving parameter for separation, not merely the rotational speed (RPM) [1] [2]. The RCF experienced by a sample is calculated using the formula: RCF = 1.118 × 10⁻⁵ × r × (RPM)², where r is the rotational radius in centimeters [1] [2]. This force is counteracted by the buoyant force (the force needed to displace the liquid medium) and the frictional force generated as particles migrate through the solution [2]. Sedimentation occurs at a constant rate only when the applied centrifugal force exceeds the sum of these counteracting forces [2].

Defining Ultracentrifugation and Its Distinctive Characteristics

Ultracentrifugation represents a specialized subset of centrifugation, optimized for spinning rotors at exceptionally high speeds to generate much greater centrifugal forces [4]. Modern ultracentrifuges are classified as instruments capable of exceeding 100,000 ×g, with some advanced models reaching forces of up to 1,000,000 ×g [1] [4]. This tremendous force enables the separation of much smaller particles—including macromolecules like proteins, nucleic acids, and even small organelles like ribosomes—that would not sediment in standard centrifuges [1] [5].

There are two primary classes of ultracentrifuges, each designed for different research objectives. The preparative ultracentrifuge is used for the actual isolation, purification, and harvesting of specific biological particles, such as cellular organelles, viruses, plasmids, and proteins [1] [4]. In contrast, the analytical ultracentrifuge (AUC) is equipped with an optical detection system for real-time monitoring of the sedimentation process [1] [5]. AUC is employed not for purification but for analyzing macromolecular properties in solution, including molecular weight, shape, composition, and conformational changes [1] [5].

Table 1: Key Specifications and Applications of Centrifuge Types

| Centrifuge Type | Typical Maximum Speed | Typical Maximum RCF | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcentrifuge | ~17,000 RPM [1] | Up to 30,000 ×g [1] | Small-volume protocols (nucleic acids, spin columns) [2] |

| Low-Speed Centrifuge | < 10,000 RPM [1] | Not specified in results | Harvesting whole cells, nuclei, chloroplasts [1] |

| High-Speed Centrifuge | ~30,000 RPM [1] | Not specified in results | Harvesting microorganisms, mitochondria, lysosomes [1] |

| Ultracentrifuge | Up to 150,000 RPM [1] | Up to 1,000,000 ×g [1] [4] | Separating membranes, ribosomes, proteins, nucleic acids [1] |

Quantitative Data and Application-Based Speed Selection

Selecting the correct centrifugal speed and force is critical for experimental success. Insufficient speed results in incomplete separation, while excessive speed can damage samples or equipment [6]. The required speed is not a single universal value but is determined by the specific characteristics of the target particle and the desired separation outcome [6].

For example, gentle pelleting of cultured cells to minimize damage typically requires low speeds of 200-300 ×g, whereas efficient pelleting of denser cell types may need 1,000-2,000 ×g [6]. In nucleic acid extraction, low speeds are used for phase separation, while higher speeds are applied for pelleting nucleic acids [6]. The most critical factor is that the centrifugal force must be specified in RCF (×g), not just RPM, to ensure reproducibility across different centrifuge models, as the same RPM will generate different forces in rotors with differing radii [2] [6].

Table 2: Guideline Centrifugation Parameters for Common Biological Applications

| Application | Typical RCF Range | Typical Use Case or Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Pelleting (Gentle) | 200 - 300 ×g [6] | For minimizing cell damage [6] |

| Cell Pelleting (Denser Cells) | 1,000 - 2,000 ×g [6] | For more efficient pelleting [6] |

| Blood Sample Processing | 500 - 3,000 ×g [6] | Lower for serum/plasma; higher for cell pelleting [6] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | 2,000 - 15,000 ×g [6] | Lower for phase separation; higher for precipitation [6] |

| Protein Fractionation | 10,000 - 20,000 ×g [6] | Separating fractions by molecular weight [6] |

| Isolating Organelles/Viruses | > 100,000 ×g [6] | Requires ultracentrifugation [6] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The success of centrifugation, particularly in density-based separations, relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Centrifugation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Centrifugation |

|---|---|

| Sucrose Density Gradients | Used for the purification and separation of cellular organelles such as mitochondria and lysosomes in swinging-bucket, fixed-angle, or vertical rotors [1] [4]. |

| Caesium Salt Gradients | Essential for the isopycnic separation of nucleic acids based on their buoyant density during ultracentrifugation [4]. |

| Iodixanol | A contrast medium used to create high-density, iso-osmotic solutions for purifying subcellular particles like vesicles and organelles [1]. |

| Fixed-Angle Rotors | Made from a single block of material (e.g., aluminum, titanium, carbon fiber); ideal for simple pelleting tasks and some gradient work in preparative ultracentrifugation [1] [4]. |

| Swinging-Bucket Rotors | Allow tubes to reorient to a horizontal plane during acceleration; ideal for density gradient purification of cells, viruses, and organelles, providing high-resolution separation [1] [4] [2]. |

| Carbon Fiber Composite Rotors | Modern rotors that are up to 60% lighter, enabling faster acceleration/deceleration and offering high corrosion resistance, which mitigates a major cause of rotor failure [4]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles by Ultracentrifugation

The following protocol, adapted from a STAR Protocols methodology, details the isolation of extracellular vesicles (EVs) from bone marrow-derived macrophages, a common application of preparative ultracentrifugation in cell biology research [7].

Materials and Equipment

- Cell Culture Supernatant: Conditioned media from bone marrow-derived macrophages.

- Centrifuge Tubes: Ultracentrifuge-compatible tubes (e.g., polypropylene, polycarbonate).

- Refrigerated Low-Speed Centrifuge [1].

- Preparative Ultracentrifuge capable of achieving 100,000 ×g or higher [4] [5].

- Fixed-Angle or Swinging-Bucket Rotor compatible with ultracentrifuge tubes.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), sterile and cold.

- 0.22 µm Pore Size Sterile Filters.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Collection and Pre-Clearing: a. Collect the cell culture supernatant containing the secreted extracellular vesicles. b. Perform an initial centrifugation at 400 ×g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet intact cells and large cellular debris [5] [7]. c. Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new tube without disturbing the pellet. d. Centrifuge the supernatant at 10,000-20,000 ×g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove larger vesicles, apoptotic bodies, and organellar debris [5]. e. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm filter to remove any remaining large particles.

Ultracentrifugation: a. Transfer the clarified supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes, ensuring they are properly balanced. b. Load the tubes into a pre-chilled rotor. Centrifuge at 100,000-150,000 ×g for 2 hours at 4°C [5] [7]. This high-force step pellets the exosomes and smaller extracellular vesicles. c. After the run, carefully decant and discard the supernatant. A small, translucent pellet should be visible at the bottom of the tube.

Washing and Final Resuspension: a. To increase purity, gently wash the pellet by resuspending it in a large volume of cold, sterile PBS. b. Repeat the ultracentrifugation step (100,000-150,000 ×g for 2 hours at 4°C) to re-pellet the washed vesicles [5]. c. Finally, carefully discard the supernatant and resuspend the final EV pellet in a small volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of PBS or an appropriate storage buffer. d. The isolated EVs are now ready for downstream characterization, such as nanoparticle tracking analysis, western blotting, or functional studies [5].

Advanced Protocol: Analytical Ultracentrifugation for Protein Characterization

Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) is a powerful method for studying the hydrodynamic properties and oligomeric states of macromolecules in solution without the need for fixation or labeling [5] [8]. The following protocol outlines a sedimentation velocity experiment.

Materials and Equipment

- Analytical Ultracentrifuge (e.g., Beckman Optima XL-I) equipped with UV/Vis absorbance and/or interference optical systems [8].

- Analytical Rotor (e.g., An-50 Ti) [8].

- Double-Sector Centerpieces (e.g., charcoal-filled Epon) [8].

- Purified Protein Sample in a suitable buffer.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample and Buffer Preparation: a. Purify the protein of interest to homogeneity. b. Dialyze the protein extensively into a matched buffer (e.g., 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150-300 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT) that will be used as the reference blank [8]. Accurate buffer matching is critical to prevent artifactual signals.

Cell Assembly: a. Load the protein sample into one sector of a double-sector centerpiece. b. Load the exact matched dialysis buffer into the reference sector. c. Assemble the centerpiece, windows, and housing into the AUC cell according to the manufacturer's instructions, ensuring a leak-free seal. d. Load the assembled cell into the analytical rotor, recording its precise position.

Centrifugation and Data Acquisition: a. Place the rotor in the pre-equilibrated ultracentrifuge. b. Set the experimental parameters: temperature (e.g., 20°C), rotor speed (e.g., 36,000 - 42,000 RPM), and run duration [8]. c. Start the run. The optical system will periodically scan the cell, collecting concentration data of the sedimenting boundary along the radius of the cell over time.

Data Analysis: a. After the run, use specialized software such as SEDFIT to analyze the sedimentation velocity data [8]. b. Fit the data to a model (e.g., continuous c(s) distribution) to obtain the sedimentation coefficient (s) distribution. c. Using auxiliary programs like Sednterp, calculate the partial specific volume of the protein based on its amino acid sequence, as well as the density and viscosity of the solvent [8]. d. The sedimentation coefficient and diffusion coefficient can be used to calculate the molecular weight and infer the oligomeric state and shape of the macromolecule [5] [8].

Centrifugation is a cornerstone technique in biomedical and biological research for separating particles based on their physical properties. By applying centrifugal force, this process enables researchers to isolate specific cells, organelles, and macromolecules from complex mixtures, forming the foundation for downstream analysis and experimentation in drug development and basic science [9]. The technique operates on fundamental physics principles—primarily centrifugal force, sedimentation, and buoyant density—which collectively determine the behavior of particles in a centrifugal field.

When a sample is rotated at high speed, an outward force acts on the particles, causing denser components to migrate away from the axis of rotation while less dense components are displaced toward the center. This results in the formation of a pellet at the bottom of the tube (containing the most dense particles) and a supernatant (containing the lighter particles) [9]. The efficacy of separation depends on several factors including particle size, shape, density, and the properties of the suspension medium [9]. For research into cell components, these principles allow for the precise isolation of organelles such as nuclei, mitochondria, and ribosomes, which is critical for understanding cellular functions and developing therapeutic interventions.

Core Physical Principles

Centrifugal Force and Sedimentation

Centrifugal force is the apparent outward force experienced by an object moving in a curved path. In a centrifuge, this force acts radially from the center of rotation, causing the movement and sedimentation of particles suspended in the sample [9]. This force is quantified as the Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF) or "g-force," which is a multiple of the Earth's gravitational acceleration. The RCF is calculated using the formula: [ RCF = 1.118 \times 10^{-5} \times r \times (RPM)^{2} ] where ( r ) is the rotational radius in centimeters, and ( RPM ) is the speed in revolutions per minute.

Sedimentation is the process by which denser particles settle at the bottom of a sample tube under the influence of centrifugal force [9]. The rate of sedimentation is governed by the size, shape, and density of the particles, with heavier and denser particles sedimenting faster [9]. During rapid centrifugation, particles sediment into a compact mass known as a pellet at the base of the tube, while the remaining liquid medium, called the supernatant, can be separated for further analysis [9].

Buoyant Density

Buoyant density is the density at which a particle neither sinks nor floats when suspended in a density gradient medium. It is a fundamental property exploited in advanced centrifugation techniques to separate particles with similar sizes but different densities [10]. In density gradient centrifugation, a medium such as sucrose or cesium chloride is used to create a column of fluid with increasing density from top to bottom [9] [11]. When a sample is centrifuged through this gradient, particles migrate until they reach a position where their density matches the density of the surrounding medium—their isopycnic point [10]. This allows for the high-resolution separation of biomolecules like proteins and nucleic acids based on their intrinsic buoyant densities rather than just their size [11].

Centrifugation Techniques for Cell Component Separation

Several centrifugation techniques have been developed to isolate and purify cellular components, each leveraging the core physical principles in different ways to achieve specific separation goals.

Differential Centrifugation: This technique utilizes multiple sequential centrifugation steps at progressively higher speeds and centrifugal forces to separate components primarily by size. Initial low-speed spins pellet larger components like whole cells, nuclei, and cytoskeletal elements. The resulting supernatant is then subjected to higher speeds to sediment smaller organelles such as mitochondria and lysosomes. Finally, very high-speed centrifugation pellets microsomes and ribosomes [9] [12]. While straightforward, this method typically yields fractions enriched in specific components rather than achieving absolute purity.

Density Gradient Centrifugation: This method offers higher resolution by separating particles based on their buoyant density. A sample is layered atop a pre-formed density gradient medium and centrifuged. Particles migrate through the gradient until they reach their isopycnic point, forming distinct bands that can be individually harvested [9] [10]. Common gradient media include Ficoll-Paque, Percoll, and sucrose for separating organelles and cesium chloride for purifying nucleic acids [10]. This technique is further refined in ultracentrifugation, which operates at extremely high speeds (up to 150,000 RPM) to separate smaller molecules like DNA, RNA, and proteins [11].

Ultracentrifugation: Operating at speeds from 60,000 to 150,000 RPM, ultracentrifuges are indispensable for separating macromolecules and subcellular components [11]. It comes in two forms:

- Preparative Ultracentrifugation: Used for the isolation and purification of specific particles, such as viral particles, ribosomal subunits, and macromolecules, via techniques like differential and density gradient centrifugation [11].

- Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): Equipped with optical detection systems, AUC allows researchers to monitor sedimentation in real-time. This provides insights into hydrodynamic properties, molecular masses, stoichiometries, and conformational changes of macromolecules [11] [13]. A specialized form of AUC, the band-forming experiment (BFE), allows for the study of reactions and mixtures with minimal sample consumption by overlaying a sample onto a denser solution [13].

The workflow below illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate centrifugation technique based on the research goal.

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Isolation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) using Density Gradient Centrifugation

This protocol details the separation of PBMCs from whole blood, a critical first step in immunology research and cellular therapy development [10].

Principle: Whole blood is layered over a density gradient medium. During centrifugation, red blood cells and granulocytes sediment through the medium, while PBMCs, which have a lower density, band at the plasma-gradient interface [10].

Materials:

- Whole blood (anti-coagulated with EDTA or heparin)

- Density gradient medium (e.g., Ficoll-Paque, Lymphoprep, density ~1.077 g/mL)

- Sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Centrifuge with swing-out rotor

- Centrifuge tubes (e.g., 15 mL or 50 mL)

- SepMate tubes or standard centrifuge tubes [10]

Method:

- Dilution: Dilute anti-coagulated whole blood with an equal volume of PBS to reduce viscosity.

- Layering: Carefully layer the diluted blood slowly over an equal volume of density gradient medium in a centrifuge tube. For SepMate tubes, add the medium first, insert the funnel, then layer the diluted blood [10].

- Centrifugation:

- Centrifuge at 400-450 x g for 30 minutes at room temperature.

- Ensure the centrifuge brake is OFF to prevent gradient disturbance [10].

- Harvesting: After centrifugation, four layers will be visible: plasma (top), PBMC band (opaque interface), density gradient medium, and pellet (red blood cells & granulocytes).

- Carefully aspirate the upper plasma layer.

- Transfer the opaque PBMC band at the interface to a new sterile tube using a pipette.

- Washing: Resuspend the harvested cells in a large volume (e.g., 10-50 mL) of PBS. Centrifuge at 250-350 x g for 10 minutes to wash. Discard the supernatant.

- Repeat Wash: Repeat the washing step once more to ensure removal of platelets and gradient medium.

- Resuspension: Resuspend the final PBMC pellet in an appropriate buffer or culture medium for counting and downstream applications.

Protocol 2: Subcellular Fractionation of Liver Tissue using Differential Centrifugation

This protocol is designed to isolate major organelles (nuclei, mitochondria) from liver tissue for metabolic and functional studies [12].

Principle: Homogenized tissue is subjected to a series of centrifugation steps at increasing RCF. Larger, denser organelles pellet at lower speeds, while smaller organelles require higher forces [12].

Materials:

- Fresh liver tissue

- Homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA) kept ice-cold

- Dounce homogenizer

- Refrigerated centrifuge with fixed-angle or swing-out rotor

- Centrifuge tubes

Method:

- Homogenization:

- Rinse liver tissue in ice-cold homogenization buffer.

- Mince the tissue finely with scissors and place it in a Dounce homogenizer with a small volume of buffer.

- Homogenize with 10-15 strokes of a loose-fitting pestle, keeping the sample on ice.

- Low-Speed Spin:

- Transfer the homogenate to a centrifuge tube.

- Centrifuge at 1,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- The resulting pellet (P1) contains nuclei, heavy membranes, and unbroken cells.

- The supernatant (S1) is carefully transferred to a new tube.

- Medium-Speed Spin:

- Centrifuge supernatant S1 at 10,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- The resulting pellet (P2) is enriched with mitochondria, lysosomes, and peroxisomes.

- The supernatant (S2) is transferred to a new tube.

- High-Speed Spin:

- Centrifuge supernatant S2 at 100,000 x g for 60 minutes at 4°C.

- The resulting pellet (P3) contains microsomal fragments (derived from endoplasmic reticulum) and plasma membranes.

- The final supernatant (S3) represents the cytosolic fraction.

- Homogenization:

The following workflow summarizes the sequential steps of this differential centrifugation protocol.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful cell component separation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and consumables. The table below details key solutions and their functions in centrifugation workflows.

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Centrifugation-Based Separation

| Item | Function/Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient Media | Creates a density column for separating particles based on buoyant density. | Ficoll-Paque, Percoll, OptiPrep, Cesium Chloride (CsCl) [10] |

| Isotonic Buffers | Maintains osmotic balance during homogenization and centrifugation to prevent organelle damage. | Sucrose, Mannitol buffers [12] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Added to buffers to prevent proteolytic degradation of sample components during processing. | Commercial cocktails (e.g., PMSF, EDTA) |

| Centrifuge Rotors | Holds sample tubes during centrifugation; choice affects separation efficiency and time. | Fixed-Angle Rotor, Swing-Out Bucket Rotor [14] [11] |

| Specialized Tubes | Tubes designed for specific protocols to simplify layering and harvesting steps. | SepMate Tubes [10] |

| Immunomagnetic Beads | Antibody-coated magnetic particles for high-purity positive or negative selection of specific cell types. | Used in Immunomagnetic Cell Separation [10] |

Quantitative Data and Operational Parameters

Precise control of operational parameters is critical for reproducible results. The following tables summarize key quantitative data for centrifugation protocols.

Table 2: Centrifugation Parameters for Blood Component Separation [14]

| Application | Recommended Speed | Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF) | Time | Rotor Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Diagnostics | ~4,000 RPM | ~2,270 x g | < 15 minutes | Swing-Out Rotor |

| Research Applications | ~6,500 RPM | ~3,873 x g | < 15 minutes | Fixed-Angle Rotor |

| PBMC Isolation | 400 - 450 x g | 400 - 450 x g | 30 minutes (brake off) | Swing-Out Rotor [10] |

Table 3: Ultracentrifuge Operational Specifications and Applications [11]

| Parameter | Typical Range | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational Speed | 60,000 - 150,000 RPM | Higher speeds separate smaller particles like proteins and nucleic acids. |

| Relative Centrifugal Force | Up to 1,000,000 x g | Sufficient force to sediment ribosomes and viral particles. |

| Application - Preparative | N/A | Pelleting of mitochondria, ribosomes, viruses; density gradient separation of DNA/RNA. |

| Application - Analytical | N/A | Determination of molecular mass, stoichiometry, and conformational changes. |

Mastering the physics of centrifugal force, sedimentation, and buoyant density is essential for designing and executing effective cell separation protocols. From the straightforward size-based separation of differential centrifugation to the high-resolution, density-based purification achievable with ultracentrifugation, these techniques provide a powerful toolkit for dissecting cellular complexity. As the field advances with innovations in automation, smart sensors, and improved materials, the precision and efficiency of these methods will continue to grow, further empowering research and drug development efforts aimed at understanding and treating human disease [15] [16]. The protocols and data summarized in this document provide a foundational guide for researchers to apply these principles reliably in the laboratory.

Within the context of centrifugation and ultracentrifugation for cell component separation research, the selection of an appropriate rotor is a critical determinant of experimental success. The rotor, the component of the centrifuge that holds the sample tubes, directly influences the efficiency, resolution, and quality of the separation process. The two predominant rotor designs used in laboratories are the fixed-angle rotor and the swinging-bucket rotor (also commonly referred to as a swing-out rotor). Each type possesses distinct geometric and functional characteristics that make it uniquely suited for specific applications in biochemistry, molecular biology, and drug development. Fixed-angle rotors hold sample tubes at a constant angle, typically between 30° and 45°, throughout the centrifugation run [17] [18]. In contrast, swinging-bucket rotors hold tubes in buckets that are hinged; when the rotor spins, these buckets swing outward to a position that is essentially horizontal (90°) to the axis of rotation [19] [20]. This fundamental difference in operation dictates the path length of particle sedimentation, the final location of the pellet, the relative centrifugal force (RCF) that can be achieved, and the overall suitability for various separation protocols. For researchers isolating subcellular organelles, nucleic acids, or proteins, understanding this core instrumentation is essential for optimizing purity, yield, and viability of delicate samples.

Technical Comparison: Fixed-Angle vs. Swinging-Bucket Rotors

The choice between a fixed-angle and a swinging-bucket rotor involves balancing multiple performance characteristics, including speed, pellet formation, sample throughput, and application-specific requirements. The following table summarizes the key operational differences between these two rotor types, providing a structured overview for informed decision-making.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Fixed-Angle and Swinging-Bucket Rotors

| Characteristic | Fixed-Angle Rotor | Swinging-Bucket Rotor |

|---|---|---|

| Rotor Geometry | Tubes are held at a fixed angle (typically 30°-45°) [17] [18] | Buckets swing out to a horizontal position (90°) during operation [19] [20] |

| Pellet Formation | Pellet forms at an angle on the side of the tube [17] [21] | Pellet forms evenly at the very bottom of the tube [17] [18] |

| Maximum Speed/RCF | Generally higher maximum speeds and g-forces [17] [20] | Lower maximum speeds and g-forces due to higher metal stress on moving parts [19] [17] |

| Typical Capacity | Holds a greater number of tubes due to efficient spacing [22] [20] | Typically holds fewer tubes to accommodate the swinging mechanism [17] [21] |

| Sedimentation Time | Shorter run times due to higher achievable g-force [19] [18] | Longer run times are often required [18] |

| Key Advantages | High g-force, compact pellets, high sample throughput, shorter run times [19] [17] | Ideal pellet location, superior for gradient separations, high vessel flexibility [19] [18] |

| Common Applications | Pelleting cells, organelles, and macromolecules (DNA, RNA, proteins); high-speed and ultracentrifugation [17] [23] | Density gradient centrifugation; pelleting live cells; phase-separation (e.g., phenol-chloroform); clinical separations [17] [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Cell Component Separation

Protocol 1: Rapid Pelleting of Bacterial Cells Using a Fixed-Angle Rotor

This protocol is designed for the efficient harvesting of bacterial cells from a culture broth, leveraging the high-speed capabilities of a fixed-angle rotor to minimize processing time.

Principal Reagents and Materials:

- Fixed-angle centrifuge rotor (e.g., capable of holding 50 mL tubes)

- Centrifuge tubes (50 mL, conical-bottom, compatible with the target RCF)

- Bacterial culture broth

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) or appropriate wash buffer

- Benchtop centrifuge or high-speed centrifuge

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Aseptically transfer the bacterial culture into pre-chilled 50 mL centrifuge tubes. Ensure tubes are filled symmetrically to within 0.1 g for balance.

- Rotor Loading: Securely place the tubes in the fixed-angle rotor. Directly opposite positions must contain tubes of equal mass.

- Centrifugation Parameters:

- Temperature: 4°C

- Speed / RCF: 5,000 - 10,000 x g [22]

- Duration: 10-20 minutes

- Acceleration/Deceleration: Use default or "fast" profiles unless specified otherwise.

- Post-Centrifugation Handling: After the run, carefully remove the tubes. The bacterial pellet will be firmly compacted on the outer side of the tube at an angle. Decant the supernatant promptly without disturbing the pellet.

- Pellet Resuspension: Resuspend the pellet in an appropriate volume of cold PBS or lysis buffer by gentle pipetting or vortexing.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Diffuse Pellet: Increase centrifugation time or RCF. Ensure the rotor angle is appropriate for forming a compact pellet (e.g., 45°) [19].

- Pellet Disturbance during Supernatant Removal: Use a vacuum aspirator with a fine tip, taking care to position the tip opposite the pellet.

Protocol 2: Density Gradient Separation of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) Using a Swinging-Bucket Rotor

This protocol outlines the isolation of PBMCs from whole blood using a Ficoll-Paque density gradient, a application that necessitates the use of a swinging-bucket rotor to preserve the integrity of the gradient layers during acceleration and deceleration.

Principal Reagents and Materials:

- Swinging-bucket centrifuge rotor

- Sterile centrifuge tubes (15 mL or 50 mL, round-bottom preferred)

- Ficoll-Paque PLUS or equivalent density gradient medium

- Whole blood (anticoagulated with EDTA or heparin)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) diluted 1:1 with sterile saline

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Gradient Preparation: Gently layer 5 mL of diluted whole blood slowly down the side of a 15 mL tube containing 5 mL of Ficoll-Paque. Maintain a sharp interface between the two layers.

- Rotor Loading: Carefully place the prepared tubes into the buckets of the swinging-bucket rotor. Ensure buckets are properly seated on their hinges.

- Centrifugation Parameters:

- Temperature: 20°C (room temperature)

- Speed / RCF: 400 x g

- Duration: 30-40 minutes

- Acceleration: Use the lowest available setting (e.g., "soft start" or 1-2) to prevent mixing of the layers.

- Deceleration: Ensure the brake is OFF to avoid disturbing the established gradient layers after centrifugation [19] [18].

- Post-Centrifugation Handling: After centrifugation, the tube will show distinct layers: plasma at the top, then a PBMC ring at the Ficoll-plasma interface, followed by the Ficoll solution, and finally, granulocytes and erythrocytes at the bottom.

- Cell Harvesting: Carefully aspirate the upper plasma layer. Using a sterile pipette, harvest the opaque PBMC ring at the interface and transfer it to a new tube.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Blurred Interface/Gradient Disruption: Ensure the brake is disabled during deceleration. Practice layering technique to avoid disturbing the Ficoll interface.

- Low PBMC Yield: Use fresh blood and avoid vibrations during centrifugation that can mix layers.

Visualization of Separation Dynamics

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental differences in sample orientation and particle sedimentation paths between the two rotor types, which underpin their distinct application profiles.

Diagram 1: Centrifuge Rotor Separation Dynamics. This workflow contrasts the operational principles of fixed-angle and swinging-bucket rotors, highlighting the differences in tube orientation, sedimentation path length, and final pellet or gradient formation.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of the aforementioned protocols relies on the use of specific, high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions required for experiments in cell component separation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Centrifugation-Based Separations

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque | A density gradient medium for the isolation of mononuclear cells from whole blood or other cell suspensions by density-based separation. | Ficoll-Paque PLUS [17] |

| Lysis Buffers | Solutions containing detergents and salts designed to disrupt cell membranes and release intracellular components for subsequent pelleting of organelles or nucleic acids. | RIPA Buffer for protein extraction; SDS-based buffers for DNA/RNA isolation. |

| Protease & Nuclease Inhibitors | Essential additives to lysis buffers to prevent the degradation of proteins and nucleic acids by endogenous enzymes during cell fractionation. | EDTA, PMSF, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets. |

| PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline) | An isotonic, pH-balanced solution used for washing cell pellets and resuspending samples without causing osmotic shock. | 1X PBS, pH 7.4 |

| Tris-based Buffers | Common buffering agents used in molecular biology to maintain stable pH during the separation and resuspension of biological macromolecules like DNA and RNA. | TE Buffer (Tris-EDTA), TAE/TBE for electrophoresis. |

The biopharmaceutical industry is navigating a period of unprecedented change, marked by significant scientific innovation alongside considerable economic and regulatory challenges. Key market drivers include the accelerating pace of novel therapeutic modalities, intensifying patent expiration pressures, and the transformative potential of artificial intelligence and advanced analytics in drug discovery and development [24] [25] [26]. Against this backdrop, robust and reliable laboratory techniques for biomolecule separation, particularly centrifugation and ultracentrifugation, have become indispensable for ensuring drug quality, characterizing complex biologics, and de-risking the development pipeline. These techniques provide the critical analytical foundation upon which the industry's progress is built, enabling researchers to isolate, purify, and analyze cellular components with high precision.

Key Market Drivers in Biopharma and Clinical Research

The strategic direction of the biopharmaceutical sector is being shaped by several powerful, interconnected trends. These drivers are influencing investment decisions, R&D prioritization, and the operational models of successful companies.

Table 1: Key Drivers in the Biopharmaceutical Market

| Market Driver | Impact on the Industry | Implications for Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Rise of Novel Modalities [25] | Shift from small molecules to complex therapeutics like gene therapies, CAR-T, and other advanced modalities; novel modalities projected to make up ~15% of the market by 2030, up from 5% in 2020. | Creates a need for more sophisticated analytical techniques, like AUC, to characterize size, aggregation, and interaction of large biomolecules. |

| The Patent Cliff [24] [26] | Drugs accounting for an estimated $175B-$300B in revenue facing patent expiration by 2030, eroding sales of established products. | Increases pressure to efficiently develop new blockbusters and biosimilars, requiring highly productive R&D and robust process development. |

| Portfolio Optimization & Therapeutic Area Focus [25] [26] | Hyper-competition in key areas like oncology; focused companies see a 65% increase in shareholder return vs. 19% for diversified firms. | Demands deep expertise in specific disease biology and necessitates tools for fail-fast decision-making and efficient target validation. |

| AI and Data-Driven R&D [25] [26] | AI can reduce preclinical discovery time by 30-50% and lower costs by 25-50%; over 40% of traditional pharma have yet to materially adopt AI. | Requires high-quality, reliable data from foundational techniques (e.g., centrifugation) to train models and validate AI-designed candidates. |

| Geopolitical and Supply Chain Shifts [24] [25] | Complexities in global trade, tariffs, and the rise of China as an innovation hub (15% of global pipeline assets, up from 4% in 2012). | Drives need for resilient supply chains and rigorous, standardized quality control across globally sourced materials and products. |

Centrifugation and Ultracentrifugation: Core Protocols for Cell Component Separation

The separation of cellular components is a foundational step in understanding disease mechanisms, identifying drug targets, and characterizing biopharmaceutical products. The following protocols detail standard methods for isolating key organelles and analyzing macromolecular assemblies.

Protocol: Isolation of Mononuclear Cells from Whole Blood Using Density Gradient Centrifugation

Principle: This method separates cells based on their buoyant density. When centrifuged, blood components partition into layers: platelets and plasma remain in the plasma layer, mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, monocytes) form a buffy coat just above the density gradient medium, while granulocytes and erythrocytes pellet at the bottom [27] [28].

Materials:

- Lymphoprep or Ficoll-Paque density gradient medium [28]

- Fresh whole blood, anti-coagulated with EDTA or heparin

- Sterile Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS)

- Centrifuge with a swinging-bucket rotor

- SepMate tubes (optional) or standard conical centrifuge tubes [28]

Method:

- Dilution: Dilute whole blood 1:1 with DPBS or saline and mix gently.

- Layering: Carefully layer the diluted blood sample over the density gradient medium in a centrifuge tube. For a 15 mL tube, use 5 mL of Lymphoprep and carefully layer 10 mL of diluted blood on top without mixing the layers.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 400 x g for 30 minutes or 1200 x g for 20 minutes at Room Temperature (15-25°C). The brake must be set to OFF to prevent disturbance of the gradients [28].

- Harvesting: After centrifugation, use a pipette to carefully aspirate the upper plasma layer. Then, collect the mononuclear cell layer (the cloudy interface between the plasma and the gradient medium) and transfer it to a new clean tube.

- Washing: Resuspend the harvested cells in a large volume (e.g., 10-15 mL) of DPBS or culture medium. Centrifuge at 300 x g for 5-10 minutes at Room Temperature with the brake ON to pellet the cells [28].

- Final Pellet: Discard the supernatant and gently resuspend the cell pellet in an appropriate buffer or medium for downstream applications.

Protocol: Differential Centrifugation for Subcellular Fractionation

Principle: This technique sequentially separates organelles from a cell homogenate based on their size and density by applying progressively higher centrifugal forces. Larger, denser organelles pellet at lower speeds, while smaller ones require higher speeds [29] [12].

Materials:

- Homogenization buffer (e.g., 0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA) kept ice-cold

- Cell culture or tissue sample

- Dounce homogenizer or similar

- Refrigerated centrifuge with fixed-angle rotor

Method:

- Homogenization: Wash and resuspend cells in ice-cold homogenization buffer. Homogenize on ice using a Dounce homogenizer (e.g., 20-30 strokes) until >90% of cells are lysed. Keep the homogenate on ice at all times [12].

- Low-Speed Spin (Nuclei & Debris): Transfer the homogenate to a centrifuge tube. Centrifuge at 1,000 x g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Pellet: Contains nuclei, heavy membranes, and unbroken cells.

- Supernatant (S1): Carefully decant and keep for the next step.

- Medium-Speed Spin (Mitochondria, Lysosomes, Peroxisomes): Transfer supernatant S1 to a new tube. Centrifuge at 10,000 x g for 15-20 minutes at 4°C.

- Pellet: Contains mitochondria, lysosomes, and peroxisomes.

- Supernatant (S2): Carefully decant and keep for the next step.

- High-Speed Spin (Microsomes): Transfer supernatant S2 to a new tube. Centrifuge at 100,000 x g for 60 minutes at 4°C using an ultracentrifuge.

- Pellet: Contains microsomes (fragments of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus) and plasma membrane fragments.

- Supernatant (S3): The final supernatant contains the soluble cytosolic fraction.

Protocol: Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) for Assessing Protein Aggregation

Principle: Sedimentation velocity AUC is a critical, label-free method for directly quantifying protein aggregation and determining the sedimentation coefficient of macromolecules in solution. It is considered an orthogonal method to verify data from size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) [30].

Materials:

- Purified protein sample in its final formulation buffer

- Reference buffer (matching the sample buffer)

- Analytical ultracentrifuge equipped with absorbance and/or interference optics

- Double-sector centerpieces

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Clarify the protein sample and reference buffer by centrifugation (e.g., 15,000 x g for 10 minutes) to remove any particulate matter. Sample testing is conducted in the exact or nearly exact liquid formulation of the biopharmaceutical [30].

- Cell Assembly: Load ~400 µL of reference buffer into one sector of a double-sector centerpiece and an equal volume of protein sample into the other sector. Assemble the cell housing securely.

- Equilibration: Place the cell in the rotor and install the rotor in the ultracentrifuge. Allow the system to equilibrate to the set temperature (typically 20°C) under vacuum without spinning.

- Data Acquisition: Start the centrifugation run at a high speed (e.g., 40,000-50,000 rpm). Collect continuous scans of absorbance (at 280 nm or other relevant wavelength) or interference versus radial position over time (e.g., every 2-5 minutes).

- Data Analysis: Use software like SEDFIT to model the sedimentation data. The analysis generates a continuous sedimentation coefficient distribution [c(s)], which provides a high-resolution profile of the sample's oligomeric state, revealing the presence of monomers, aggregates, and fragments [30].

Table 2: Centrifugation Parameters for Specific Cell Types and Applications

| Application / Cell Type | Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF) | Time | Temperature | Brake |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular Cell Washing [28] | 300 x g | 5 - 10 min | Room Temperature | On |

| Gentle Cell Washing [28] | 100 x g | 5 - 6 min | Room Temperature | On |

| Platelet Removal [28] | 120 x g | 10 min | Room Temperature | Off |

| Processing Neurospheres [28] | 90 x g | 5 min | Room Temperature | On |

| Isolating Mononuclear Cells (Ficoll) [28] | 400 x g | 30 min | Room Temperature | Off |

| Mitochondrial Isolation [12] | 10,000 x g | 15-20 min | 4°C | On |

Workflow Visualization: From Homogenate to Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a multi-technique approach to subcellular fractionation and component analysis, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of separation protocols relies on a set of key reagents and materials, each serving a specific function to ensure purity, viability, and integrity of the isolated components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cell Fractionation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient Media (e.g., Lymphoprep, Ficoll-Paque, Sucrose) [28] [12] | Separation of blood components or subcellular organelles based on buoyant density. | Pre-formulated, sterile, with defined density. Inert and non-toxic to cells. |

| Homogenization Buffers [12] | Medium for cell lysis and suspension of homogenate. | Typically isotonic (e.g., containing 0.25 M sucrose or mannitol) to prevent osmotic shock; includes protease inhibitors. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to homogenization and lysis buffers to prevent proteolytic degradation of proteins during fractionation. | Broad-spectrum or specific; often used as a mixture to inhibit serine, cysteine, aspartic, and metalloproteases. |

| Chromatography Resins [29] [12] | Further purification of proteins from isolated fractions. | Includes ion-exchange (IEC), size-exclusion (SEC), and affinity resins (e.g., Protein A, glutathione-sepharose). |

| Antibodies for Specific Markers (e.g., against TOM20 for mitochondria, Lamin A/C for nuclei) [12] | Identification and validation of organelle purity and integrity via Western Blot or immunofluorescence. | High-specificity, well-validated antibodies are critical for accurate assessment. |

From Theory to Bench: Proven Protocols for Cell Component Isolation

Centrifugation and ultracentrifugation are foundational techniques in life sciences, enabling the precise separation of cellular components based on physical properties like size, density, and shape. These methods are indispensable for protein purification and analysis, forming the cornerstone of research in biochemistry, molecular biology, and biopharmaceutical development [31] [32]. The ability to isolate high-purity proteins is critical for understanding disease mechanisms, evaluating drug effects, and discovering new biomarkers [33]. This application note details advanced protocols and methodologies that leverage centrifugation techniques within a broader research framework focused on cell component separation, providing researchers with robust tools for their experimental workflows.

Key Centrifugation Techniques for Cell Fractionation

The separation of cellular components primarily relies on two principal centrifugation methods: differential centrifugation and density gradient centrifugation. Each technique exploits different physical properties of particles to achieve separation and is suited for particular applications and sample types.

- Differential Centrifugation: This method separates particles primarily based on their mass and size through a series of increasing centrifugal forces. Larger and heavier components sediment faster and pellet at lower centrifugal forces, while smaller, lighter components require higher speeds and longer durations. A key characteristic is that it is typically performed without specialized separation reagents [34]. It is most effectively used for the separation of cells and larger organelles [34]. A common application is the preparation of a buffy coat from whole blood [34].

- Density Gradient Centrifugation: This technique separates particles based primarily on their density. Samples are spun in a pre-formed gradient medium with a known density profile. Particles will migrate until they reach a position in the gradient where their own density matches that of the surrounding medium [34]. This process requires density-known medium reagents (e.g., sucrose, Percoll) to form the gradient [34]. It is particularly useful for separating molecules, particles, and cells of similar size but different densities, such as separating white blood cells from red blood cells [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Centrifugation Techniques for Cell Fractionation.

| Feature | Differential Centrifugation | Density Gradient Centrifugation |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Mass and size | Density |

| Reagent Requirement | Not required | Requires density gradient media |

| Typical Applications | Separating cells and organelles; preparing buffy coat from whole blood [34] | Separating molecules and particles; isolating specific cell populations like PBMCs [34] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity and straightforward protocol [34] | High specificity for separating particles with similar sizes but different densities [34] |

Advanced Protein Purification Protocol

SpyDock-Modified Epoxy Resin for Affinity Purification

Traditional affinity chromatography (AC) methods, such as His-tag purification, often face limitations including high resin costs and the need for additional tag-removal steps to obtain the native protein. The following protocol describes a robust and cost-effective alternative using SpyDock-modified epoxy resin coupled with a pH-inducible self-cleaving intein for direct purification of proteins with authentic N-termini [35].

Key Features of the Method:

- Authentic N-Termini: Delivers purified proteins without the need for post-purification tag removal [35].

- High Purity and Yield: Achieves >90% purity with yields comparable to commercial His-tag methods [35].

- Cost-Effectiveness: The resin is easy to prepare and reusable, reducing long-term costs [35].

Experimental Protocol:

- Resin Preparation: Synthesize the SpyDock-modified epoxy resin by conjugating the SpyDock protein to epoxy-activated resin according to established Spy chemistry protocols [35].

- Cell Lysis and Clarification:

- Resuspend the cell pellet expressing the target protein (fused to the SpyTag-intein construct) in an appropriate lysis buffer.

- Lyse the cells using a method suitable for your cell type (e.g., sonication, homogenization).

- Clarify the cell lysate by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove cellular debris [35].

- Affinity Binding:

- Incubate the clarified lysate with the prepared SpyDock-modified resin for 1-2 hours at room temperature with gentle mixing to allow covalent binding between SpyTag and SpyDock [35].

- Washing:

- Wash the resin extensively with a suitable wash buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline) to remove non-specifically bound contaminants [35].

- Elution via Intein Cleavage:

- Induce on-column self-cleavage of the intein by applying a mild pH shift (e.g., to pH 6.0-7.0) and incubating at 4°C for 16-24 hours.

- Collect the eluate, which contains the purified target protein with an authentic N-terminus [35].

- Resin Regeneration:

- Regenerate the resin for reuse by washing with a low-pH buffer (e.g., 0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.5) followed by re-equilibration in the storage buffer [35].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this purification protocol:

Performance Metrics

This method has been quantitatively evaluated against traditional approaches. The following table summarizes key performance data for the SpyDock-modified resin method compared to a standard His-tag purification.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of SpyDock-Modified Resin for Protein Purification [35].

| Parameter | SpyDock-Modified Resin Method | Traditional His-Tag Method |

|---|---|---|

| Purity | >90% | >90% |

| Yield | Comparable to His-tag | Benchmark |

| Tag Removal | Not required (authentic N-terminus) | Additional enzymatic step required |

| Resin Reusability | Yes, multiple cycles | Limited |

Advanced Cell Sorting via Fluidized Bed Centrifugation

For the separation of viable and non-viable cells at a large scale, fluidized bed centrifugation (FBC) presents a novel, scalable solution. This technology is particularly valuable for intensifying biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes, such as continuous perfusion cultivation [36].

Principle of Operation: An FBC system captures mammalian cells inside a rotating chamber where a counter-flow of fluid is applied. Cells are captured at a position where the hydrodynamic drag force equals the opposing centrifugal force [36]. Since the drag force decreases from the chamber inlet to the outlet while the centrifugal force remains relatively constant, a sorting effect occurs: larger, viable cells are enriched in the tip of the chamber, while smaller, non-viable cells and debris are enriched near the outlet and can be washed out [36].

Experimental Protocol for Viable Cell Sorting:

- System Setup: Use a single-use FBC system (e.g., Ksep series). For small-scale trials, a system with 25 mL chambers is appropriate [36].

- Parameter Configuration:

- Cell Loading and Overloading: Load the cell broth from the bioreactor into the FBC chamber. To achieve sorting, intentionally overload the centrifuge chambers to ensure a fully packed bed, which enhances the separation based on cell size and viability [36].

- Washing for Separation: Wash the captured cells by exchanging approximately 2.6 times the chamber volume with fresh cell culture media. This washing step elutes non-viable cells and debris, which are collected in the flow-through [36].

- Harvesting Viable Cells: The enriched fraction of viable cells can be recovered from the chamber and directly transferred back into a bioreactor for subsequent cultivation [36].

- Process Integration: This sorting method can be applied periodically during a cultivation process to maintain high culture viability and productivity, enabling innovative process strategies like continuous fed-batch [36].

The separation mechanism within the FBC chamber is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the described protocols requires specific reagents and materials. The following table lists key solutions for centrifugation-based separation and advanced protein purification.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Purification and Cell Separation.

| Item | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient Media (e.g., Sucrose, Percoll) | Reagents with known density used to form a separation gradient during centrifugation [34]. | Density gradient centrifugation for isolating specific cell populations (e.g., PBMCs from blood) or organelles [34]. |

| SpyDock-Modified Epoxy Resin | A custom affinity resin that covalently binds to SpyTag-fused proteins, enabling purification without tag removal [35]. | Affinity chromatography for purifying proteins with authentic N-termini [35]. |

| pH-Inducible Self-Cleaving Intein | A protein segment that, when fused to a target protein, undergoes self-cleavage in response to a mild pH shift [35]. | Used in conjunction with SpyTag/SpyDock for eluting the purified target protein from the resin [35]. |

| Single-Use FBC Chambers | Disposable consumables for fluidized bed centrifuges, designed for sterile processing of cell cultures [36]. | Large-scale, sterile sorting of viable and non-viable mammalian cells in bioprocessing [36]. |

The centrifugation-based methods detailed in this application note—from fundamental density gradient separation to advanced fluidized bed sorting and innovative affinity purification—provide powerful and scalable strategies for protein analysis and cell component separation. The SpyDock-intein purification protocol offers a robust path to high-purity proteins with native sequences, while fluidized bed centrifugation addresses modern bioprocessing challenges by enabling viable cell sorting. Integrating these techniques into research and development workflows can significantly enhance productivity, yield, and efficiency in both basic life science research and industrial biopharmaceutical applications.

Lipoprotein profiling is a cornerstone of cardiovascular disease research and diagnostic medicine, providing critical insights into lipid metabolism and atherogenic risk. The accurate separation and analysis of lipoprotein subclasses are technically challenging yet essential for understanding their distinct biological functions and roles in disease pathogenesis. Density-based ultracentrifugation remains the foundational methodology for isolating lipoproteins from biological fluids, leveraging their intrinsic physicochemical properties for purification [29]. This protocol details the application of sequential ultracentrifugation techniques for the comprehensive separation of major lipoprotein classes, supplemented by contemporary analytical methods for characterization. The methodologies described herein are designed to support basic research on lipoprotein biology, preclinical drug development, and the refinement of diagnostic assays requiring high-resolution fractionation.

Principles of Lipoprotein Separation

Lipoproteins are complex macromolecular assemblies comprising a hydrophobic core of triglycerides and cholesteryl esters surrounded by an amphiphilic monolayer of phospholipids, free cholesterol, and apolipoproteins. The core principle underlying their separation via ultracentrifugation is differential buoyant density, a property dictated by their lipid-to-protein ratio [29] [37].

- Density Ranges: Each major lipoprotein class occupies a characteristic and non-overlapping density range in solution. Chylomicrons are the least dense (<0.95 g/mL), followed by VLDL (0.95-1.006 g/mL), IDL (1.006-1.019 g/mL), LDL (1.019-1.063 g/mL), and HDL (1.063-1.21 g/mL) [37].

- Centrifugal Force: When subjected to a powerful centrifugal field, particles in a solution experience a force proportional to their mass and the square of the angular velocity. In a medium adjusted to a specific density, lipoproteins will either sediment or float based on whether their intrinsic density is greater or less than that of the surrounding medium [29].

- Fractionation Strategy: Sequential ultracentrifugation involves adjusting the density of the serum or plasma sample and applying precisely controlled centrifugal forces for defined durations. This process allows for the step-wise isolation of lipoprotein classes in order of increasing density, yielding fractions suitable for downstream biochemical, cellular, or molecular analyses [29].

Experimental Protocols

Density Gradient Ultracentrifugation for Lipoprotein Fractionation

This protocol describes the isolation of VLDL, LDL, and HDL from human serum or plasma using a discontinuous density gradient, which provides superior resolution and purity compared to sequential flotation.

Materials:

- Preparative Ultracentrifuge: Capable of maintaining temperatures at 4-16°C and achieving forces up to 500,000 × g [29].

- Ultracentrifuge Tubes: Polypropylene or similar compatible tubes (e.g., 5-13 mL volume).

- Density Solutions: Prepare stock solutions of NaCl, KBr, or NaCl/NaBr for density adjustment. Validate density using a densitometer.

- Serum/Plasma Sample: Fresh or previously frozen (-80°C) EDTA-plasma or serum.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw frozen plasma/serum on ice. Add a preservative cocktail (e.g., 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% sodium azide, 1 μM aprotinin) to inhibit oxidation and proteolysis.

- Density Adjustment: Adjust the density of the sample to 1.30 g/mL by adding solid KBr (approximately 0.326 g/mL of plasma). Dissolve gently to avoid denaturation.

- Gradient Formation: In an ultracentrifuge tube, layer the following solutions sequentially to form a discontinuous gradient:

- 2.5 mL of density-adjusted sample (d=1.30 g/mL)

- 2.5 mL of NaCl-KBr solution (d=1.182 g/mL)

- 2.5 mL of NaCl-KBr solution (d=1.063 g/mL)

- 2.5 mL of NaCl solution (d=1.019 g/mL)

- Top up with a NaCl solution (d=1.006 g/mL)

- Ultracentrifugation:

- Rotor: Use a swinging-bucket rotor (e.g., SW 41 Ti).

- Conditions: Centrifuge at 200,000 × g at 16°C for 24 hours.

- Fraction Collection: After centrifugation, carefully fractionate the tube contents from the top using a pipette or a tube slicer. The bands, from top to bottom, will correspond to:

- VLDL (d < 1.006 g/mL)

- IDL (d=1.006-1.019 g/mL)

- LDL (d=1.019-1.063 g/mL)

- HDL (d=1.063-1.21 g/mL)

- Post-Processing: Dialyze individual fractions against a buffer such as Tris-EDTA (pH 7.4) to remove salt and concentrate if necessary using centrifugal filters. Determine protein or cholesterol concentration before use.

Centrifugation Parameter Optimization for Solubility and Stability

The integrity of lipoprotein structure and function during separation is highly sensitive to centrifugation parameters. Systematic optimization is required to balance separation efficiency with biomolecular preservation.

Critical Parameters:

- Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF) and Time: Excessive force or duration can disrupt lipoprotein integrity. A systematic study on phase separation found that lower-speed centrifugation (e.g., 5 min at 5000 rpm/~2180 × g) yielded results closest to the reference sedimentation method, while higher speeds (10,000 rpm/~8720 × g for 20 min) caused overestimation of solubility in heterogeneous systems, likely due to forced suspension of colloids [38].

- Rotor Type: Fixed-angle rotors generally yield faster separations, while swing-out rotors provide better resolution for density gradients, as their particle path is straighter [29] [39].

- Temperature Control: Maintain centrifugation at 4-16°C to minimize lipid oxidation and microbial growth, especially during long runs.

The workflow below summarizes the key decision points for method selection and optimization.

Analytical Techniques for Lipoprotein Characterization

Following fractionation, isolated lipoproteins require comprehensive characterization. The table below compares the primary analytical methods used.

Table 1: Analytical Techniques for Lipoprotein Characterization

| Method | Principle | Measured Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Assays [37] | Chromogenic reactions specific to cholesterol, triglycerides, or phospholipids. | Concentration of specific lipids in a fraction. | High-throughput, automated, low cost. | Requires pre-separation; measures bulk lipid, not particle nature. |

| 2D Diffusion-Ordered NMR Spectroscopy [40] | Diffusion coefficients and NMR signals of lipoprotein subclasses. | Particle number (LDL-P, HDL-P), size distribution. | Rapid, no separation needed, measures particle number. | High instrument cost; complex data analysis. |

| Gel Filtration Chromatography [29] | Size-based separation via porous beads. | Hydrodynamic size, approximate molecular weight. | Preserves native structure; can be scaled. | Lower resolution than ultracentrifugation; may dilute sample. |

| Immunoassays [37] [41] | Antibody-based detection of specific apolipoproteins. | ApoB, ApoA-I, Lp(a) concentration. | High specificity and sensitivity. | Cross-reactivity possible; requires specific antibodies. |

Advanced Applications and Clinical Correlations

Lipoprotein(a) Profiling

Lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), is a genetically determined, atherogenic lipoprotein particle similar to LDL but containing a unique glycoprotein, apolipoprotein(a) [41]. Its measurement is critical for advanced risk assessment.

- Clinical Significance: Elevated Lp(a) is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), aortic stenosis, and thrombosis [41]. Levels are largely genetically determined and remain stable throughout life.

- Measurement Methods: Immunoassays (immunoturbidimetry or immunonephelometry) are standard [37]. Results can be reported in mass units (mg/dL) or molar concentration (nmol/L), with high risk defined as >50 mg/dL or >100 nmol/L [42] [41].

- Centrifugation Considerations: Lp(a) resides in a density range overlapping with LDL and HDL. Precise isolation often requires a combination of ultracentrifugation and subsequent immunoaffinity chromatography for pure preparations.

Impact on Cardiovascular Risk Assessment

Advanced lipoprotein profiling provides data that refines clinical risk assessment beyond standard lipid panels.

- Risk Stratification Targets: Contemporary guidelines, including the 2025 ESC/EAS update, recommend aggressive, risk-based LDL-C targets:

- <70 mg/dL for high-risk individuals

- <55 mg/dL for very-high-risk individuals

- <40 mg/dL for those at extreme risk [42].

- Non-HDL-C and ApoB: These are increasingly recognized as superior targets, as they reflect the total burden of all atherogenic lipoproteins (VLDL, IDL, LDL, Lp(a)). Non-HDL-C is calculated as Total Cholesterol minus HDL-C, with a target of 30 mg/dL higher than the corresponding LDL-C goal [43] [37]. ApoB measurement provides a direct count of atherogenic particles [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful lipoprotein profiling relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lipoprotein Profiling

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Density Gradient Salts | Adjust solvent density for ultracentrifugation. | NaCl, KBr, NaBr. Purity: >99.5%. Prepare stock solutions with verified density. |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits | Quantify cholesterol, triglycerides, phospholipids in fractions. | Commercially available kits based on cholesterol oxidase-peroxidase (CHO-POD) or glycerol-3-phosphate oxidase peroxidase (GPO-POD) methods [37]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Size-based separation (gel filtration) or affinity purification. | Cross-linked agarose or dextran beads (e.g., Sepharose, Sephadex); immunoaffinity resins with anti-ApoB or anti-ApoA-I antibodies. |

| Collection Tubes | Blood sample integrity for lipid analysis. | EDTA tubes for plasma (inhibits coagulation); serum separation tubes; plain glass tubes for PRF [39]. |

| Buffer Additives | Preserve sample integrity during processing. | EDTA (chelator, inhibits oxidation), Sodium Azide (antimicrobial), Protease Inhibitor Cocktails. |

Mastering the techniques of lipoprotein and cholesterol profiling through ultracentrifugation is fundamental for advancing lipid metabolism research and developing new therapeutic strategies. This detailed protocol emphasizes that method robustness depends on a thorough understanding of both the physicochemical principles of separation and the careful optimization of centrifugation parameters to preserve native lipoprotein structure. The integration of these classic separation methods with modern analytical platforms like 2D NMR and high-sensitivity immunoassays provides a powerful, multi-dimensional view of lipoprotein biology, directly feeding into both basic science and the evolution of precision medicine for cardiovascular disease.

Exosomes, small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) ranging from 30–200 nm in diameter, are released by virtually all cell types and are present in biological fluids such as blood, urine, and saliva [44] [45]. These nanoscale vesicles act as crucial messengers in intercellular communication, carrying a functional molecular cargo (proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids) from their parent cells [45]. Because their composition often reflects the physiological or pathological state of their cell of origin, exosomes have emerged as a promising source of biomarkers for a wide array of diseases, including cancer, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular conditions [44] [46].

The isolation of exosomes is a critical first step in the research pipeline. The inherent heterogeneity of exosomes, the complexity of biological fluids, and the presence of nanoscale contaminants like lipoproteins make their isolation a significant challenge [46]. The choice of isolation method directly impacts the yield, purity, and biological integrity of the recovered exosomes, thereby influencing the reliability and reproducibility of all subsequent analyses [47] [45]. This article provides a detailed comparison of prevailing and emerging isolation techniques, with a special focus on the role of centrifugation, and presents an optimized protocol for ultracentrifugation to aid researchers in this vital field.

Comparative Analysis of Exosome Isolation Methods

No single isolation method is perfect; each offers a different balance of yield, purity, speed, and cost. The choice depends on the specific requirements of the downstream application. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major isolation techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Exosome Isolation Methods

| Method | Principle | Purity | Yield/Recovery | Time | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Ultracentrifugation (UC) | Size & density sedimentation via centrifugal force [46] | Medium [46] [45] | Low to Medium [46] [48] | >4 hours (Time-consuming) [45] | Considered the "gold standard"; simple operation; suitable for large sample volumes [46] [45] | Low repeatability; may damage exosome integrity; requires expensive instrumentation [46] [45] |

| Density Gradient Centrifugation | Buoyant density in a medium [46] | High [46] [45] | Low [46] | >16 hours (Time-consuming) [45] | High purity; separates exosomes from non-vesicular particles [46] | Complex operation; time-consuming [45] |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Particle size & hydrodynamic properties [49] [45] | High [46] [45] | Relatively Low [46] | ~20 minutes (Fast) [46] | Maintains exosome integrity and function; simple and fast [46] [45] | Sample volume limited; can be contaminated by similar-sized particles (e.g., lipoproteins) [46] [47] |

| Polymer-Based Precipitation | Alters solubility & dispersibility using polymers (e.g., PEG) [47] [45] | Low [46] [45] | High [46] [49] | 30 min - 12 hours [45] | Simple; high yield; no specialized equipment needed [46] | Co-precipitates contaminants (e.g., lipoproteins); polymers may interfere with downstream analysis [46] |

| Immunoaffinity Capture | Antibody binding to specific surface markers (e.g., CD63, CD81) [46] [49] | High [46] | Relatively Low [46] | Information Missing | Isolates specific exosome subpopulations; high specificity [46] | Expensive; low yield; requires specific antibodies [46] [49] |

| Ultrafiltration | Membrane filtration by size [47] | Low [46] | High [46] | Faster than UC [47] | Simple; no specialized equipment; good for large volumes [46] | Shear stress may damage exosomes; membrane clogging [47] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Size, affinity, or other properties on a miniaturized platform [46] | High [46] | High [46] | Ultra-fast [46] | High throughput; high purity; portable integration; low sample loss [46] | Emerging technology; can be complex [46] |

Recent comparative research underscores the practical implications of method selection. A 2025 study found that while PEG-based precipitation (CP) yielded the highest concentration of particles, the combination of precipitation with ultrafiltration (CPF) resulted in superior purity and more specific exosome marker expression (CD9) with minimal non-vesicular artifacts [49]. In contrast, ultracentrifugation, while widely used, often yielded the lowest particle concentration [49]. Another 2024 optimization study for urinary sEVs found that extending ultracentrifugation time to 48 minutes and replacing a large vesicle (LEVs) pelleting step with simple filtering increased sEV recovery by 1.7-fold. Furthermore, a washing step was shown to decrease sEV yield by half, highlighting the need for protocol-specific optimization [48].

Detailed Protocol: Isolation of Small Extracellular Vesicles from Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages (BMDMs) by Ultracentrifugation

The following protocol, adapted from a 2025 STAR Protocols article, details the isolation of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs) from mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages using ultracentrifugation, a method suitable for many cell culture models [50].

Pre-isolation Requirements and Reagent Preparation

- Institutional Permissions: All animal experiments must be approved by the relevant Animal Care and Use Committee [50].

- Preparation of EV-Depleted FBS: Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) contains bovine EVs that contaminate the sample.

- Heat-inactivate FBS by incubating in a 56°C water bath for 30 minutes.

- Ultracentrifuge the heat-inactivated FBS at 100,000 × g for 120 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect the supernatant and sterilize it using a 0.22 μm syringe filter. This EV-depleted FBS is used for preparing the cell culture medium [50].

- Key Reagents and Equipment:

- Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF): Reconstitute lyophilized powder to 0.1–0.5 mg/mL in sterile PBS. Avoid vortexing; pipette gently [50].

- Cell Culture Medium: Use DMEM high-glucose medium supplemented with 10% EV-depleted FBS and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin [50].

- Ultracentrifuge and Rotor: Pre-cool to 4°C before use. A fixed-angle rotor (e.g., P45AT) with appropriate tubes (e.g., 70PC) is required [50].

Step-by-Step Isolation Workflow

Graphical workflow of the sEV isolation protocol from BMDMs

Procedure:

- Generate BMDMs: Isolate bone marrow from mouse tibia and femur and culture it in complete medium with M-CSF for 7 days to differentiate into macrophages [50].

- Harvest Supernatant: Culture the generated BMDMs under desired polarization conditions. Collect the cell culture supernatant and proceed immediately or store at 4°C for short periods [50].

- Low-Speed Centrifugation: Centrifuge the supernatant at 300 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to pellet intact cells. Transfer the supernatant to a new tube [50].

- Intermediate-Speed Centrifugation: Centrifuge the resulting supernatant at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove dead cells and large debris. Transfer the supernatant to ultracentrifuge tubes [50].

- High-Speed Centrifugation: Centrifuge the supernatant at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet large extracellular vesicles (LEVs) and apoptotic bodies. Carefully transfer the supernatant to new ultracentrifuge tubes [50].

- Ultracentrifugation (sEV Pellet): Ultracentrifuge the supernatant at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C to pellet the small EVs (sEVs). Note: Optimized protocols for urine suggest that 48-60 minutes at 200,000 × g can improve recovery [48].

- Wash sEVs (Optional): Resuspend the sEV pellet in a large volume of sterile, cold PBS. Perform a second ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 70 minutes at 4°C. Note: This step improves purity but can significantly reduce yield [48].

- Resuspend and Store: Discard the supernatant and resuspend the final sEV pellet in 50-100 μL of sterile PBS. Aliquot and store at -80°C [50].

Critical Parameters for Centrifugation Optimization

The efficiency of sedimentation during centrifugation is governed by several key factors, as described by the simplified equation for sedimentation time [51]:

t ≅ (6π × η × l) / (d² × (ρ − ρ₀) × G)

Where:

- t: Sedimentation time

- η: Viscosity of the suspension

- l: Pathlength of suspension in the centrifuge tube

- d: Diameter of the particle (e.g., exosome)

- ρ and ρ₀: Densities of the particle and solvent, respectively

- G: Centrifugal force (RCF)

Table 2: Key Factors Influencing Centrifugation Efficiency

| Factor | Impact on Sedimentation | Practical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Viscosity (η) of water is 25% lower at 25°C than at 4°C, reducing sedimentation time [51]. | For temperature-sensitive samples, balance the need for speed with preserving bioactivity. Pre-cool rotors and use a temperature-controlled centrifuge. |

| Solution Viscosity (η) & Osmolarity | Viscosity is influenced by the salt concentration and type (kosmotropes increase η, chaotropes decrease η) [51]. | Use consistent, physiologically balanced buffers (e.g., PBS). Be aware that changing buffers between steps alters viscosity. |

| Relative Centrifugal Force (RCF or G-force) | Higher RCF decreases sedimentation time. Always use RCF (× g), not RPM, for reproducibility across rotors [51]. | Calculate RCF using the formula: RCF = (1.118 × 10⁻⁵) × r × (RPM)², where 'r' is the radius in cm. |

| Rotor Type & Tube Angle | The effective pathlength (l) and sedimentation dynamics are affected by the rotor geometry. Inclined rotors can enhance separation rates via the "Boycott effect" [52]. | Fixed-angle rotors are standard. For protocols, note the rotor type and k-factor, which describes its clearing efficiency. |

Post-Isolation Characterization and The Scientist's Toolkit