Cellular Crossroads: Decoding the Biochemical Pathways of Regeneration During Infection

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate biochemical pathways that govern cellular regeneration in the context of infection.

Cellular Crossroads: Decoding the Biochemical Pathways of Regeneration During Infection

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on the intricate biochemical pathways that govern cellular regeneration in the context of infection. It explores foundational mechanisms, from damage sensing and metabolic reprogramming to immune cell recruitment and function. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content details advanced methodological approaches—including genetic engineering, biomaterial scaffolds, and novel platforms like LEVA—for studying and manipulating these pathways. It further addresses key challenges in therapeutic translation, such as overcoming chronic inflammation and metabolic interference, and provides a comparative analysis of emerging regenerative strategies against traditional approaches. The review concludes by evaluating the clinical potential of these interventions and outlining future directions for harnessing endogenous repair mechanisms to improve outcomes in infectious and inflammatory diseases.

The Molecular Blueprint: How Cells Sense Damage and Initiate Regeneration During Infection

The immune system employs a sophisticated surveillance network to detect tissue injury and microbial invasion, serving as a critical initial phase in the subsequent processes of inflammation, tissue repair, and regeneration. This detection system relies on the recognition of two major classes of molecules: pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) derived from microorganisms, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by stressed or damaged host cells [1] [2]. Both PAMPs and DAMPs are sensed by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed on immune and non-immune cells, initiating signaling cascades that activate both innate and adaptive immunity [3] [4].

Within the context of biochemical pathways in cell regeneration during infection, this initial recognition represents a crucial "Signal 0" that primes the tissue microenvironment for subsequent repair processes [4]. The interplay between these danger signals and their receptors not only determines the magnitude of the inflammatory response but also significantly influences stem cell activation, differentiation, and functional tissue restoration [5]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of DAMPs, PAMPs, and PRRs, with a specific focus on their integrated roles in injury detection and the initiation of regenerative pathways.

Molecular Patterns in Injury and Infection

Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs)

DAMPs are endogenous molecules with defined intracellular functions that acquire immunostimulatory properties when released into the extracellular space during cellular stress, injury, or non-programmed cell death [4] [6]. They function as critical alarmins that alert the innate immune system to unscheduled cell death and tissue damage, initiating and perpetuating immunity in response to trauma, ischemia, and sterile injury [4]. DAMPs can be broadly classified by their molecular characteristics and subcellular origins (Table 1).

Table 1: Major DAMPs and Their Characteristics

| DAMP Category | Representative Members | Subcellular Origin | Primary PRRs Engaged |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Proteins | HMGB1, Histones | Nucleus | TLR2, TLR4, TLR9, RAGE |

| Heat Shock Proteins | HSP70, HSP90 | Cytosol | TLR2, TLR4 |

| Metabolic Intermediates | ATP, Uric Acid | Cytosol | P2X7, NLRP3 |

| Nucleic Acids | mtDNA, dsRNA, exRNA | Nucleus, Mitochondria | TLR9, TLR3, RIG-I, cGAS |

| Extracellular Matrix Components | Hyaluronan fragments | Extracellular Matrix | TLR2, TLR4, CD44 |

| Chromatin-Associated (CAMPs) | eCIRP, HMGB1, Histones | Nucleus | TLR4, TREM-1, RAGE |

Key DAMPs of Clinical Significance:

- High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1): A nuclear DNA-binding protein that translocates to the cytoplasm and is released during cell necrosis or secreted by activated immune cells. Extracellular HMGB1 promotes inflammation through multiple receptors, including TLR4, RAGE, and TREM-1 [7] [6]. It acts as a chemotactic factor, recruits immune cells, and synergistically enhances the inflammatory response to LPS.

- Extracellular ATP: A crucial metabolic DAMP released through plasma membrane channels or via passive leakage during necrosis. It activates the P2X7 receptor, leading to NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and subsequent maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 [5] [6].

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): Shares structural similarities with bacterial DNA (unmethylated CpG motifs) and is recognized by TLR9 and the cGAS-STING pathway, triggering type I interferon responses [7].

- Extracellular Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (eCIRP): A newly identified chromatin-associated molecular pattern (CAMP) that is released during cellular stress and activates TLR4 and TREM-1, contributing to inflammation in shock states [6].

DAMP release occurs through both passive and active mechanisms. Passive release occurs during necrotic cell death due to loss of membrane integrity. Active release can involve specialized secretory pathways, extracellular trap formation (ETosis) by neutrophils and macrophages, and through gasdermin pores formed during pyroptosis [6].

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs)

PAMPs are conserved, essential molecular structures shared by broad classes of microorganisms but absent in the host, enabling the immune system to distinguish between "self" and "non-self" [4] [8]. They represent the "stranger" signal that triggers immune activation upon infection.

Table 2: Characterized PAMPs and Their Microbial Sources

| PAMP | Chemical Nature | Microbial Source | Primary PRRs Engaged |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Glycolipid | Gram-negative Bacteria | TLR4/MD-2 |

| Lipoteichoic Acid (LTA) | Glycolipid | Gram-positive Bacteria | TLR2 |

| Peptidoglycan (PGN) | Glycopolymer | Bacteria (Cell Wall) | TLR2, NOD2 |

| Flagellin | Protein | Bacterial Flagella | TLR5, NLRC4 |

| Unmethylated CpG DNA | DNA | Bacteria, Viruses | TLR9 |

| dsRNA | Double-stranded RNA | Viruses | TLR3, RIG-I, MDA5 |

| ssRNA | Single-stranded RNA | Viruses | TLR7, TLR8 |

| β-glucan | Polysaccharide | Fungi | Dectin-1 |

Major PAMPs and Their Recognition:

- Bacterial Endotoxins (LPS): A component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, LPS is one of the most potent PAMPs. Its recognition requires a complex of TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 [9] [8]. Activation of this receptor complex initiates a robust pro-inflammatory response, primarily through the MyD88 and TRIF signaling pathways, leading to the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and type I interferons.

- Bacterial Nucleic Acids: Unmethylated CpG DNA motifs, common in bacterial genomes, are sensed by intracellular TLR9 [10]. Viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), a replication intermediate for many viruses, is recognized by TLR3 and the RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs) in the cytosol [4] [2].

- Peptidoglycan (PGN): A major component of the cell wall of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, PGN is sensed by extracellular TLR2 and the intracellular receptor NOD2 [10].

It is important to note that the term Microbial-Associated Molecular Patterns (MAMPs) has been proposed to include molecules from non-pathogenic commensals, reflecting the broader role of PRR signaling in maintaining homeostasis with the microbiome [8].

Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs): Sensors of Danger

PRRs are germline-encoded host proteins that act as sensors for PAMPs and DAMPs. They can be broadly categorized into membrane-bound and cytosolic receptors, each with distinct ligand specificity and subcellular localization [2].

Major Families of PRRs

Toll-like Receptors (TLRs): The most well-characterized PRR family. TLRs are transmembrane proteins located on the plasma membrane or endosomal membranes. They recognize a wide variety of PAMPs and DAMPs [3] [2].

- Cell Surface TLRs: Include TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6, and TLR10 (non-functional in mice), which primarily recognize lipid, protein, and lipoprotein patterns.

- Endosomal TLRs: Include TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9, and TLR13 (mice), which specialize in recognizing microbial nucleic acids.

NOD-like Receptors (NLRs): A large family of cytosolic receptors. Some NLRs, like NOD1 and NOD2, sense bacterial peptidoglycan fragments and activate NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Others, such as NLRP3, form multi-protein complexes called inflammasomes in response to a wide range of DAMPs and PAMPs, leading to caspase-1 activation and maturation of IL-1β and IL-18 [1] [2].

RIG-I-like Receptors (RLRs): Cytosolic RNA sensors (RIG-I, MDA5) that detect viral RNA and initiate antiviral type I interferon responses [2].

C-type Lectin Receptors (CLRs): Primarily recognize carbohydrate structures on fungi, mycobacteria, and other pathogens [2].

AIM2-like Receptors (ALRs) and Other Cytosolic DNA Sensors: AIM2 forms an inflammasome in response to cytosolic DNA. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) is a major DNA sensor that produces the second messenger cGAMP, which activates the STING pathway to induce type I interferons [3] [2].

PRR Signaling Pathways

Engagement of PRRs by their ligands triggers intricate intracellular signaling cascades that culminate in the activation of transcription factors such as Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and Interferon Regulatory Factors (IRFs), leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and type I interferons [5] [2].

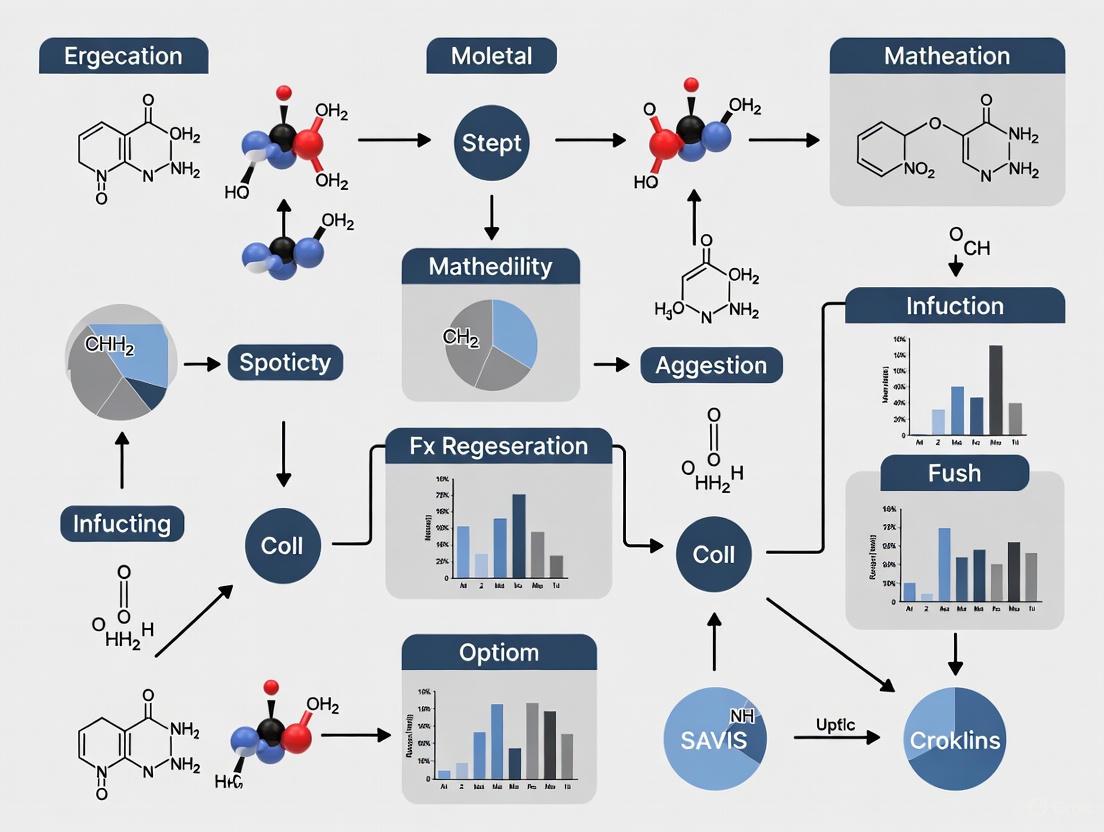

The diagram below illustrates the major PRR signaling pathways.

Experimental Methodologies for Studying PRR Signaling

In Vitro Ligand-Recognition Assays

Objective: To validate direct binding between a specific PAMP/DAMP and its putative PRR, and to quantify the binding affinity.

Detailed Protocol:

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR):

- Immobilization: The purified recombinant PRR (e.g., TLR ectodomain) is immobilized on a sensor chip.

- Ligand Injection: Serial dilutions of the purified ligand (e.g., LPS, HMGB1) are flowed over the chip.

- Kinetic Analysis: The association and dissociation rates are measured in real-time by tracking changes in the refractive index at the chip surface. Data is fitted to a binding model to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), and kinetic constants (kon, koff) [2].

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and Pull-Down Assays:

- Cell Lysis: Cells expressing the PRR of interest are lysed under non-denaturing conditions.

- Ligand Incubation: The cell lysate is incubated with the biotinylated ligand or a ligand-conjugated bead.

- Precipitation: Streptavidin beads (for biotinylated ligand) or protein A/G beads (for antibody-based IP) are added to capture the ligand-receptor complex.

- Analysis: Precipitated complexes are washed, eluted, and analyzed by Western blotting to detect the co-precipitated PRR.

Functional Cell-Based Signaling Assays

Objective: To determine the functional consequences of PRR activation in a relevant cellular context.

Detailed Protocol:

Reporter Gene Assays:

- Transfection: HEK293T cells (often null for many endogenous PRRs) are co-transfected with:

- A plasmid expressing the PRR of interest.

- A reporter plasmid (e.g., an NF-κB, AP-1, or ISRE promoter driving firefly luciferase expression).

- A control plasmid (e.g., Renilla luciferase under a constitutive promoter) for normalization.

- Stimulation: 24-48 hours post-transfection, cells are stimulated with the candidate PAMP/DAMP.

- Measurement: Cell lysates are prepared, and luciferase activity is measured using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system. Firefly luciferase activity is normalized to Renilla to calculate fold induction over unstimulated controls.

- Transfection: HEK293T cells (often null for many endogenous PRRs) are co-transfected with:

Cytokine/Chemokine Profiling:

- Cell Culture: Primary immune cells (e.g., bone marrow-derived macrophages, dendritic cells) or relevant cell lines are plated.

- Stimulation: Cells are treated with the PRR ligand. To confirm specificity, include inhibitors (e.g., TAK-242 for TLR4) or PRR-specific antagonists.

- Quantification: After 6-24 hours, cell culture supernatants are collected. Secreted cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-β) are quantified using ELISA or multiplex bead-based immunoassays (Luminex) [7].

Western Blot Analysis of Signaling Intermediates:

- Stimulation and Lysis: Cells are stimulated for various durations (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60 min) and lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Electrophoresis and Blotting: Lysates are separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane.

- Detection: Membranes are probed with phospho-specific antibodies against key signaling molecules (e.g., p-IκBα, p-p38, p-JNK, p-IRF3) and corresponding total protein antibodies to confirm equal loading.

Genetic Models for In Vivo Validation

Objective: To establish the non-redundant physiological role of a specific PRR or DAMP in injury and infection models.

Detailed Protocol:

- Gene-Targeted Mice:

- Knockout Models: Utilize mice with global or cell-specific deletion of the gene encoding the PRR (e.g., Th4-/-, Nlrp3-/-) or DAMP (e.g., Hmgb1-/-).

- Disease Modeling: Subject knockout and wild-type control mice to relevant disease models:

- Sterile Injury: Trauma, ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), acetaminophen-induced liver injury.

- Infection: Polymicrobial sepsis (e.g., cecal ligation and puncture), bacterial pneumonia, viral infection.

- Endpoint Analysis: Compare outcomes between genotypes, including:

- Survival: Monitor for 7-14 days.

- Pathology: Histological scoring of tissue damage and inflammation (H&E staining).

- Inflammatory Mediators: Measure cytokine levels in plasma or tissue homogenates.

- Bacterial Burden: In infection models, quantify CFUs in blood and organs.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR Agonists | Ultrapure LPS (TLR4), Poly(I:C) (TLR3), CpG ODN (TLR9) | Positive control for PRR activation; study of PRR-specific responses | In vitro cell stimulation; in vivo model of inflammation |

| PRR Antagonists | TAK-242 (TLR4), ODN TTAGGG (TLR9), MCC950 (NLRP3) | Inhibit specific PRR signaling; validate PRR involvement in a response | In vitro and in vivo proof-of-concept studies |

| Neutralizing Antibodies | anti-HMGB1 mAb, anti-TLR2 mAb, anti-RAGE mAb | Block specific DAMP-PRR interactions | In vitro neutralization; therapeutic assessment in vivo |

| Reporter Cell Lines | THP1-XBlue (NF-κB/AP-1), HEK-Blue TLR cells | Sensitively measure PRR activation via secreted embryonic phosphatase (SEAP) | High-throughput screening of ligands/inhibitors |

| Cytokine Assays | ELISA Kits, Luminex Multiplex Panels | Quantify downstream inflammatory mediators (cytokines, chemokines) | Assessment of functional immune response output |

| Genetic Models | Global/Conditional KO mice (e.g., Myd88-/-, Nlrp3-/-) | Define non-redundant roles of specific signaling nodes in vivo | In vivo disease modeling of infection and injury |

DAMPs, PAMPs, and PRRs in the Context of Regeneration

The activation of PRRs by PAMPs and DAMPs creates an inflammatory milieu that profoundly influences the regenerative cascade. This "Signal 0" is instrumental in bridging initial injury detection to the activation of tissue-resident stem and progenitor cells [4] [5].

Initiating the Regenerative Cascade

Following tissue injury, the release of DAMPs such as ATP, HMGB1, and DNA fragments activates PRRs on resident macrophages and other stromal cells [5]. This triggers the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, leading to the production of chemokines (e.g., SDF-1) and cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) [5]. This inflammatory gradient serves two critical functions: it recruits immune cells to the site of damage, and it acts as a potent mobilizing signal for stem cells.

Stem Cell Mobilization and Fate Decisions

The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis is a key pathway in stem cell recruitment. DAMPs and PAMPs upregulate SDF-1 production in injured tissues. Stem cells, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), express the receptor CXCR4 and migrate along this chemotactic gradient to the injury site [5]. Once localized, the local microenvironment, which is rich in PRR ligands, growth factors, and cytokines, influences stem cell fate decisions between self-renewal and differentiation into functional lineages required for repair [5]. For instance, TLR4 signaling in MSCs has been shown to modulate their differentiation potential and paracrine functions.

Resolution and Integration

Successful regeneration requires the resolution of the initial inflammatory response. Uncontrolled or chronic DAMP/PAMP signaling, as seen in persistent infections or non-healing wounds, can lead to excessive inflammation, fibrosis, and impaired regeneration—a state of persistent inflammation immunosuppression catabolism syndrome (PICS) [7]. The transition from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-regenerative environment involves the downregulation of DAMP signaling, a shift in macrophage polarization from M1 to M2 phenotypes, and the activation of anti-inflammatory mechanisms. The ultimate integration of newly formed cells into the existing tissue architecture is crucial for restoring structural and functional homeostasis [5].

Concluding Remarks

The intricate system of injury detection via DAMPs, PAMPs, and PRRs forms the foundational layer of the body's response to damage and infection. Understanding the specific molecular interactions, signaling pathways, and functional outcomes is not only fundamental to immunology but also critical for elucidating the biochemical pathways that govern cell regeneration. The experimental frameworks detailed herein provide researchers with robust methodologies to dissect these complex processes. Targeting these interactions—for instance, with anti-DAMP antibodies or PRR antagonists—represents a promising therapeutic frontier for modulating the immune response to enhance tissue repair and regeneration in conditions ranging to trauma and sepsis to chronic inflammatory diseases [7] [6].

The process of tissue repair following infection or injury is a precisely coordinated dance between the immune system and tissue-resident stem cells. This crosstalk, essential for effective regeneration, is mediated by a complex language of secreted signaling molecules—primarily cytokines and chemokines. Within the context of infection, the initial, immune-driven pro-inflammatory response must seamlessly transition to a pro-resolution and regenerative phase to restore tissue homeostasis. Dysregulation of this dialogue is a hallmark of chronic inflammatory diseases, fibrosis, and failed regeneration. A detailed understanding of the key cytokines and chemokines that orchestrate this response is therefore critical for advancing therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. This guide details the core molecular mediators, their mechanisms of action, and the experimental frameworks used to decode them, providing a resource for researchers focused on biochemical pathways in cell regeneration during infection.

Key Cytokines Directing Immune-Stem Cell Dialogue

Cytokines are the primary signals that modulate stem cell behavior in response to immune activity. Several families play pivotal roles, with the interleukin-6 (IL-6) family being particularly prominent in stromal-immune crosstalk [11].

The IL-6 Family of Cytokines

This family, including IL-6, IL-11, Oncostatin M (OSM), and Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF), utilizes the shared glycoprotein 130 (gp130) receptor subunit for signal transduction, with specificity conferred by unique co-receptors [11]. Their roles in stem cell biology are diverse:

- IL-6 and IL-11: These cytokines signal via complexes involving IL-6R/IL-11R and gp130, with gp130 serving as the sole signaling subunit. They are produced by both immune and stromal cells in response to damage or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and can drive the acute phase response and influence stem cell proliferation [11].

- Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF): In cancer stem cells (CSCs), LIF has been shown to activate NOTCH1 signaling through epigenetic mechanisms, specifically H3K27 demethylation, thereby inducing the expression of "stemness" related genes, promoting self-renewal, and facilitating metastasis [12].

- Oncostatin M (OSM): Notably, OSM exhibits species-specific receptor usage. Human OSM can signal through either the gp130/OSMR or gp130/LIFR complex, allowing it to influence a broader range of cell types, while mouse OSM primarily signals via OSMR [11].

The IL-17/IL-22 Axis

This axis is critical in barrier tissues like the skin and gut, which are frequent sites of infection.

- IL-17 and IL-22: These cytokines are predominantly produced by immune cells such as Th17 cells, γδ T cells, and group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s) [13]. They directly act on epithelial stem cells and their progeny (e.g., keratinocytes), inducing proliferation and the production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and chemokines [13]. This creates a feed-forward loop that recruits more immune cells to the site of infection or injury.

Mediators of Resolution and Polarization

The transition from inflammation to regeneration is orchestrated by specific cytokines that promote an anti-inflammatory, pro-reparative environment.

- IL-4 and IL-13: Secreted by eosinophils and other immune cells, IL-4 is a key activator of fibro/adipogenic progenitors (FAPs), which are essential for rapid debris clearance and subsequent tissue remodeling [14].

- Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β): In conjunction with IL-6, TGF-β is required for the differentiation of naïve T cells into IL-17-producing Th17 cells, a key pathogenic population in many inflammatory conditions [13]. It also plays a major role in driving the resolution of inflammation and fibrosis.

Table 1: Key Cytokine Families in Immune-Stem Cell Crosstalk

| Cytokine Family | Key Members | Cellular Sources | Effects on Stem/Stromal Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 Family | IL-6, IL-11, OSM, LIF | Macrophages, Dendritic Cells, Stromal Cells | Promotes proliferation, self-renewal, and chemokine secretion; induces stemness in CSCs [11] [12]. |

| IL-17/IL-22 Axis | IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22 | Th17 cells, γδ T cells, ILC3s | Drives proliferation of epithelial cells/keratinocytes; induces AMP and chemokine production [13]. |

| Polarizing & Resolving | TGF-β, IL-4, IL-13 | T cells, Eosinophils, Macrophages | Drives Th17 differentiation (TGF-β+IL-6); activates FAPs for debris clearance (IL-4) [14] [13]. |

Chemokines: Orchestrating Cellular Recruitment

Chemokines form the spatial guidance system that recruits specific immune cell subsets to the stem cell niche, ensuring the right cells arrive at the right time.

Recruitment to Secondary Lymphoid Organs

Stromal cells in lymphoid organs, such as fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs), constitutively produce CCL19 and CCL21. These chemokines recruit CCR7-expressing naïve T cells and dendritic cells to the lymph nodes, which is crucial for initiating adaptive immune responses [11].

Recruitment to Sites of Damage and Infection

Upon sensing damage or infection, tissue-resident stromal cells and keratinocytes upregulate a different set of chemokines to recruit effector immune cells.

- CCL2: This is a major chemokine for monocytes. The CCL2/CCR2 axis is critical for recruiting circulating monocytes into damaged tissue; impairment of this axis results in reduced macrophage infiltration and slowed muscle regeneration [14].

- CCL20: Keratinocytes stimulated by IL-17 produce CCL20, which acts as a chemoattractant for CCR6+ Th17 cells, thereby amplifying the local inflammatory response [13].

- CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL8 (IL-8): These ELR+ CXC chemokines are potent attractants for neutrophils, which are among the first immune cells to arrive at a site of infection [13].

Table 2: Key Chemokines in Stem Cell Niche Recruitment

| Chemokine | Receptor | Cellular Sources | Recruited Cell Types | Role in Regeneration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCL19/CCL21 | CCR7 | Lymph Node FRCs [11] | Naïve T cells, Dendritic Cells | Initiates adaptive immunity in lymphoid organs. |

| CCL2 | CCR2 | Stromal Cells, Myoblasts [14] | Monocytes/Macrophages | Essential for macrophage-dependent clearance of debris and growth of new muscle fibers. |

| CCL20 | CCR6 | Keratinocytes, Stromal Cells [13] | Th17 Cells | Amplifies IL-17-driven inflammation at barrier sites. |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | CXCR1/CXCR2 | Keratinocytes, Stromal Cells [13] | Neutrophils | Early recruitment of neutrophils for phagocytosis and pro-inflammatory signaling. |

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Summarized Quantitative Data on Cytokine Actions

Table 3: Quantitative Effects of Cytokines on Stem Cell Behavior

| Cytokine/Chemokine | Target Cell | Measured Outcome | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cocktail of IL-1α, IL-13, IFN-γ, TNF-α | Muscle Stem Cells (MuSCs) | Capacity for long-term in vitro expansion | Enabled proliferation of undifferentiated MuSCs through 20 passages [14]. |

| IL-22 + IL-17A/F | Keratinocytes | Induction of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) | Synergistically induced expression of hBD-2 and S100A9; additively enhanced S100A7 and S100A8 [13]. |

| TNF-α | Macrophages / FAPs | Regulation of FAP apoptosis | M1 macrophage-derived TNF-α directly induces apoptosis of FAPs, preventing pathological fibrosis [14]. |

| Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) | MuSCs (via CCR5) | Mitogenic activation | 'Dwelling' macrophage-secreted NAMPT activates MuSCs through the CCR5 receptor [14]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Cytokine-Induced MuSC ExpansionIn Vitro

This protocol is adapted from research demonstrating the long-term expansion of functional muscle stem cells using a defined cytokine cocktail [14].

Objective: To serially expand undifferentiated, self-renewing MuSCs in culture by mimicking the endogenous inflammatory microenvironment.

Materials:

- Primary MuSCs: Isolated from mouse or human skeletal muscle.

- Growth Medium: Base medium (e.g., F-10 or DMEM) supplemented with appropriate serum or growth factors, excluding cytokines.

- Cytokine Cocktail: Recombinant mouse/human IL-1α, IL-13, IFN-γ, and TNF-α. Prepare concentrated stock solutions in sterile PBS or medium.

- Culture Vessels: Coated tissue culture plates.

- Passaging Reagents: Trypsin/EDTA or a non-enzymatic cell dissociation buffer.

- Analysis Tools: Flow cytometer for stem cell marker analysis (e.g., Pax7), and a differentiation assay (e.g., myogenic induction followed by immunostaining for Myosin Heavy Chain).

Methodology:

- Isolation and Plating: Isolate MuSCs via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or pre-plating techniques and plate them at a low density in growth medium.

- Cytokine Treatment: Add the defined cytokine cocktail (IL-1α, IL-13, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) to the culture medium. A control group should be maintained with growth medium alone.

- Maintenance and Passaging: Culture the cells at standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). Monitor cell confluence daily.

- Serial Passaging: Once cells reach 70-80% confluence, gently dissociate them using trypsin/EDTA. Count the cells and re-plate them at a low density in fresh growth medium containing the same cytokine cocktail. This constitutes one passage. Repeat this process for up to 20 passages.

- Functional Assessment:

- Proliferation Rate: Calculate the population doubling level at each passage.

- Stemness Maintenance: Analyze the percentage of Pax7-positive cells via flow cytometry at regular intervals (e.g., every 5 passages).

- Differentiation Potential: At the end of the expansion period, subject the cells to differentiation conditions and quantify the formation of multinucleated myotubes to confirm their myogenic potential.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Visualizations

IL-6 Family Cytokine Signaling Pathway

Immune-Stem Cell Crosstalk in Muscle Regeneration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagent Solutions for Studying Immune-Stem Cell Crosstalk

| Research Reagent | Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α, etc.) | Protein | Used in in vitro assays to stimulate stem or immune cells and observe downstream effects on proliferation, differentiation, and chemokine secretion [14] [13]. |

| Neutralizing/Antagonistic Antibodies | Antibody | To block specific cytokine or receptor function (e.g., anti-IL-6R, anti-TNF-α) in vitro or in vivo, allowing researchers to delineate the specific role of a single pathway [13]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibodies (CD44, CD133, EpCAM) | Antibody | Identification and purification of specific stem cell (e.g., MuSCs) or CSC populations from heterogeneous tissue samples based on surface marker expression [12]. |

| CCR2 and CCR5 Inhibitors | Small Molecule | To chemogenetically block chemokine receptor function, used to validate the role of specific recruitment axes like CCL2/CCR2 in macrophage recruitment to damaged muscle [14]. |

| JAK/STAT Inhibitors (e.g., Ruxolitinib) | Small Molecule | To inhibit downstream signaling pathways common to many cytokines (especially the IL-6 family), assessing the functional importance of these pathways in stem cell responses [11]. |

| IDO1 Inhibitors | Small Molecule | To block the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 pathway, which is used by stromal cells to limit T-cell proliferation by depleting tryptophan, thereby studying immune suppression in the niche [11]. |

Metabolic reprogramming is a fundamental mechanism by which immune cells meet the energetic and biosynthetic demands required for activation, effector function, and tissue repair during infection. This whitepaper delineates the core shifts between glycolytic and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathways, detailing how the immunologic Warburg effect—a switch to aerobic glycolysis in inflammatory cells—orchestrates protective immunity and repair. Within the context of infection research, we explore how these metabolic pathways govern cell regeneration and functional fate, providing a technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals. The document integrates structured quantitative data, experimental protocols, signaling pathway diagrams, and key research reagents to equip scientists with the tools for advanced investigation in immunometabolism.

The field of immunometabolism has established that metabolic pathways are not merely housekeeping functions but are dynamic regulators of immune cell activation, differentiation, and effector responses [15] [16]. Upon encountering pathogens, immune cells undergo a profound metabolic rewiring to support their specific functions, a process critical for effective host defense and tissue repair during infection. The two primary energy-producing pathways—glycolysis and OXPHOS—are strategically employed by different immune cell subsets to fulfill their roles. Glycolysis, even in the presence of oxygen (aerobic glycolysis or the Warburg effect), allows for rapid ATP generation and provides biosynthetic precursors for proliferating cells. OXPHOS, while more efficient in ATP yield, supports longer-term, regulatory functions [17] [15]. This whitepaper examines the shifts between these pathways within the framework of infection and repair, providing a detailed analysis of underlying mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic implications.

Core Metabolic Pathways and Their Role in Infection and Repair

The Glycolytic Switch: Warburg Effect in Innate and Adaptive Immunity

The metabolic switch from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis is a hallmark of pro-inflammatory immune cell activation. This phenomenon, akin to the Warburg effect in cancer cells, enables cells to rapidly generate ATP and biosynthetic intermediates essential for proliferation and inflammatory mediator production [15] [16].

- Macrophages and Dendritic Cells: Innate immune cells like macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) reprogram their metabolism upon sensing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) via toll-like receptors (TLRs). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activation of TLR4, for instance, induces a robust glycolytic shift, increasing glucose consumption and lactate production. This shift is crucial for supporting their antimicrobial and antigen-presenting functions. The underlying mechanisms involve upregulation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)-derived nitric oxide (NO), which inhibits mitochondrial respiration [16].

- T Lymphocytes: Naïve T cells primarily rely on OXPHOS but undergo rapid glycolytic reprogramming upon T cell receptor (TCR) engagement and CD28 co-stimulation. This switch is essential for the clonal expansion, differentiation, and effector functions of pro-inflammatory T helper 1 (Th1) and Th17 cells. Key regulators include the upregulation of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and transcription factors like Myc and HIF-1α [15] [18]. Effector T cells depend on this glycolytic metabolism to sustain interferon-gamma (IFNγ) production and cytotoxic activity [17].

- Functional Consequences: Blocking glycolysis with inhibitors like 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) impairs critical immune functions. In macrophages and DCs, it reduces production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-1β (IL-1β). In T cells, it inhibits differentiation into Th1/Th17 lineages and curtails cytokine production and cytolytic activity [19] [15] [16].

Oxidative Phosphorylation and Fatty Acid Oxidation in Regulatory Functions

In contrast to pro-inflammatory cells, anti-inflammatory and regulatory immune subsets preferentially utilize OXPHOS and fatty acid oxidation (FAO).

- Regulatory T Cells (Tregs): Tregs, which suppress inflammatory responses and promote immune tolerance, rely heavily on OXPHOS and FAO rather than glycolysis. They exhibit lower expression of GLUT1 and higher dependency on lipid uptake and oxidation. This metabolic profile supports their suppressive function and long-term persistence [17] [15].

- M2 Macrophages: Anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, associated with tissue repair and resolution of inflammation, utilize OXPHOS and FAO, relying on mitochondrial metabolism rather than glycolysis [17].

- Memory T Cells: Central memory T (TCM) lymphocytes primarily utilize FAO to support their longevity and rapid recall responses upon re-infection. Inhibition of glycolysis can actually promote the development of this long-lived memory population [15].

Table 1: Metabolic Pathways in Immune Cell Subsets

| Immune Cell Type | Primary Metabolic Pathway(s) | Key Functional Role | Key Regulatory Molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 Macrophage | Aerobic Glycolysis | Pro-inflammatory antimicrobial defense | HIF-1α, iNOS, mTOR [17] [16] |

| M2 Macrophage | OXPHOS, FAO | Anti-inflammatory tissue repair | AMPK, PPARs [17] |

| Effector T Cell (Th1/Th17) | Aerobic Glycolysis | Pro-inflammatory cytokine production | GLUT1, HIF-1α, Myc, mTOR [17] [15] |

| Regulatory T Cell (Treg) | OXPHOS, FAO | Immune suppression and tolerance | AMPK, Foxp3 [17] [15] |

| Activated Dendritic Cell | Aerobic Glycolysis | Antigen presentation, T cell priming | HIF-1α, iNOS [15] [16] |

| Memory T Cell | FAO, OXPHOS | Long-term immunity, rapid recall | AMPK, PGC1α [15] |

Metabolic Crosstalk in the Tissue Microenvironment during Infection

The metabolic state of immune cells is profoundly influenced by, and in turn influences, the tissue microenvironment during infection. Hypoxic conditions in infected tissues stabilize HIF-1α, further promoting glycolysis in infiltrating immune cells [17]. Furthermore, metabolic competition exists between host cells and pathogens, and among different immune populations. For example, pro-inflammatory glycolytic cells can deplete local glucose and produce lactate, creating an acidic environment that may suppress the function of other immune cells, including T cells [17]. This crosstalk highlights the complexity of metabolic reprogramming in vivo and its direct impact on disease outcome and tissue repair.

Pharmacological and genetic interventions have been instrumental in defining the causal role of specific metabolic pathways in immune function and antibacterial defense. The data below summarize key findings from experimental models.

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of Metabolic Pathway Blockade on Immune Functions in Bacterial Infection Models

| Experimental Intervention | Target Pathway | Effect on Neutrophils | Effect on Th1 Cell Differentiation | Antibacterial Activity In Vivo | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG) | Glycolysis (blocks hexokinase) | ↑ Population expansion↓ TNF-α secretion↓ ROS production↓ Phagocytosis | Inhibited | Inhibited in Listeria monocytogenes-infected mice | [19] |

| Dimethyl Malonate (DMM) | OXPHOS (blocks succinate) | ↑ Population expansion↓ TNF-α secretion↓ ROS production↓ Phagocytosis | Inhibited | Inhibited in Listeria monocytogenes-infected mice | [19] |

Experimental Protocols for Immunometabolism Research

Protocol: Assessing Metabolic Dependence Using Pharmacological Inhibitors

This protocol outlines a standard method for determining the reliance of specific immune functions on glycolysis or OXPHOS, using in vitro cell culture and functional assays.

1. Research Reagent Solutions

- 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG): A glucose analog that competitively inhibits hexokinase, the first enzyme in glycolysis. Prepare a 1 M stock solution in sterile water or PBS, filter sterilize (0.2 µm), and store at -20°C. Typical working concentration is 1-10 mM [19].

- Dimethyl Malonate (DMM): A cell-permeable malonate derivative that inhibits the TCA cycle enzyme succinate dehydrogenase, thereby disrupting OXPHOS. Prepare a 1 M stock solution in DMSO and store at -20°C. Typical working concentration is 1-10 mM [19].

- Oligomycin: An ATP synthase inhibitor that directly blocks OXPHOS. Prepare a 10 mM stock in DMSO and store at -20°C. Typical working concentration is 1-10 µM [15].

2. Cell Stimulation and Treatment

- Isolate primary immune cells (e.g., neutrophils, T cells, macrophages) from mouse spleen, lymph nodes, or peritoneal cavity.

- Seed cells in appropriate culture medium and stimulate with relevant agonists (e.g., LPS for macrophages, anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for T cells).

- Concurrently, add metabolic inhibitors (2-DG, DMM, Oligomycin) or vehicle control (DMSO/PBS). Include untreated and unstimulated controls.

3. Functional Assays

- Cytokine Production: After 6-24 hours of culture, collect supernatant. Quantify cytokine levels (e.g., TNF-α, IFNγ, IL-1β) via ELISA or multiplex bead-based assays [19].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production: Load cells with a fluorescent ROS sensor (e.g., CM-H2DCFDA or Dihydroethidium) and measure fluorescence by flow cytometry or fluorometry [19].

- Proliferation Assay: For T cells, label with CellTrace Violet prior to stimulation. After 72-96 hours, analyze dye dilution by flow cytometry to assess proliferation.

- Phagocytosis: Incubate cells with fluorescently labeled bacteria or latex beads. After a set time, analyze internalized fluorescence by flow cytometry, using trypan blue to quench extracellular signal [19].

4. Metabolic Phenotyping

- Extracellular Flux Analysis: Use an instrument like the Seahorse XF Analyzer to measure real-time glycolytic rates (via extracellular acidification rate, ECAR) and mitochondrial respiration (via oxygen consumption rate, OCR) in the presence of the inhibitors [20].

Protocol: In Vivo Assessment of Metabolic Reprogramming in Infection

This protocol describes how to test the role of metabolic pathways in a live animal model of bacterial infection.

1. Animal Model and Infection

- Use 8-12 week old C57BL/6 mice (or other relevant strains).

- Infect mice intravenously or intraperitoneally with a sublethal dose of Listeria monocytogenes.

- Administer metabolic inhibitors (e.g., 2-DG or DMM) or vehicle control via intraperitoneal injection, starting at the time of infection and continuing daily.

2. Sample Collection and Analysis

- At day 3-5 post-infection, euthanize animals and collect spleen and liver.

- Bacterial Burden: Homogenize organs, perform serial dilutions, and plate on agar plates to count colony-forming units (CFUs) [19].

- Immune Cell Analysis: Prepare single-cell suspensions from organs. Analyze immune cell populations (e.g., neutrophil and T cell infiltration, activation markers) by flow cytometry.

- Cytokine Measurement: Collect serum or homogenate supernatants from organs to measure systemic and local cytokine levels.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Regulation

The metabolic switch to glycolysis is orchestrated by a network of key signaling molecules and transcription factors. The following diagram illustrates the core regulatory pathway driving glycolytic reprogramming in immune cells like macrophages and T cells upon activation.

Diagram Title: Core Pathway for Glycolytic Reprogramming

Key Regulatory Nodes:

- PAMP/DAMP Sensing & TCR Engagement: Initiate the signaling cascade via surface receptors [16].

- PI3K/Akt/mTOR Axis: A central signaling hub that integrates activation signals to promote anabolic metabolism, including glycolysis. mTOR drives the expression of HIF-1α and glycolytic enzymes [17].

- HIF-1α (Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-alpha): A master transcriptional regulator of the glycolytic switch. It upregulates glucose transporters (GLUT1) and key glycolytic enzymes (LDHA, PKM2), and promotes lactate production [19] [17] [16]. It functions as an upstream signal for glycolysis in both hypoxic and normoxic conditions during inflammation.

- c-Myc: Another transcription factor induced upon T cell activation that coordinates the expression of glycolytic genes and supports metabolic reprogramming [17].

The interplay of these regulators ensures that immune cells can rapidly meet the high energetic and biosynthetic demands of activation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Immunometabolism

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose (2-DG) | Glycolysis inhibitor (Hexokinase) | To probe dependence on glycolysis for immune cell function and proliferation [19] [16]. |

| Dimethyl Malonate (DMM) | OXPHOS inhibitor (Succinate Dehydrogenase) | To disrupt mitochondrial TCA cycle and assess the role of OXPHOS [19]. |

| Oligomycin | OXPHOS inhibitor (ATP Synthase) | To directly inhibit mitochondrial ATP production and measure bioenergetic profiles [15]. |

| Rapamycin | mTOR inhibitor | To suppress the mTOR pathway and study its role in driving metabolic reprogramming and effector cell differentiation [17]. |

| Seahorse XF Analyzer | Metabolic Phenotyping Instrument | To perform real-time, live-cell analysis of glycolytic rate (ECAR) and mitochondrial respiration (OCR) [20]. |

| siRNA/shRNA for HIF-1α | Gene Knockdown | To determine the specific requirement for HIF-1α in metabolic shifts and inflammatory gene expression [16]. |

Metabolic reprogramming is a cornerstone of the immune response, with the shift between glycolysis and OXPHOS critically determining the fate and function of immune cells in infection and repair. The immunologic Warburg effect fuels pro-inflammatory, effector responses essential for pathogen clearance, while OXPHOS and FAO support regulatory, memory, and tissue-repair functions. Understanding these pathways at a mechanistic level, as detailed in this guide, provides a robust framework for developing novel therapeutic strategies. Targeting immunometabolism holds promise for modulating immune responses in infectious diseases, autoimmunity, and cancer, though challenges remain in achieving cell-specific and context-dependent modulation. Future research leveraging multi-omics approaches and spatial technologies will further decode the metabolic heterogeneity within tissue microenvironments, paving the way for precision immunotherapies.

The inflammatory cascade represents a sophisticated biological response system where the seemingly destructive process of programmed cell death is intricately connected to subsequent tissue regeneration. Central to this process is pyroptosis, a highly inflammatory form of lytic programmed cell death that occurs most frequently upon infection with intracellular pathogens [21]. This controlled cellular demise initiates a complex signaling network that eliminates compromised cells and establishes a microenvironment conducive to repair. The transition from pyroptosis to pro-regenerative signaling exemplifies a fundamental biological principle wherein destruction and reconstruction are mechanistically coupled in host defense and tissue homeostasis.

Understanding this cascade is particularly crucial for research in infection and regeneration, as it reveals how the innate immune system coordinates pathogen clearance with the restoration of tissue integrity. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the molecular mechanisms bridging pyroptotic cell death to regenerative outcomes, offering researchers in drug development a comprehensive framework for targeting these pathways in inflammatory diseases, infectious disorders, and regenerative medicine applications.

Molecular Mechanisms of Pyroptosis

Core Pyroptosis Pathways

Pyroptosis is a caspase-dependent, pro-inflammatory mode of regulated cell death characterized by gasdermin-mediated membrane pore formation, cell swelling, and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [22]. The term "pyroptosis" derives from the Greek words pyro (fire or fever) and ptosis (falling), reflecting the intense inflammatory response it triggers [21] [23]. This form of cell death functions as an essential antimicrobial mechanism by eliminating intracellular replication niches for pathogens and alerting the immune system through inflammatory signaling [21].

The core event in pyroptosis execution is the formation of pores in the plasma membrane by proteins from the gasdermin family, primarily GSDMD [24]. These pores disrupt cellular ionic gradients, resulting in water influx, cell swelling, and eventual osmotic lysis, while permitting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1β and IL-18 [21] [25]. The following table summarizes the key morphological and biochemical characteristics distinguishing pyroptosis from other forms of cell death:

Table 1: Characteristics of Pyroptosis Compared to Other Cell Death Forms

| Characteristic | Apoptosis | Pyroptosis | Necroptosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lysis | No | Yes | Yes |

| Cell Swelling | No | Yes | Yes |

| Pore Formation | No | Yes (GSDMD) | Yes (MLKL) |

| Membrane Blebbing | Yes | Yes | No |

| DNA Fragmentation | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Nucleus Intact | No | Yes | No |

| Key Executor | Caspase-3/7 | GSDMD | MLKL |

| Inflammation | No | Yes | Yes |

| Caspase-1 Activation | No | Yes | No |

Signaling Pathways Executing Pyroptosis

The Canonical Inflammasome Pathway

The canonical pathway begins when pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as NOD-like receptors (NLRs) or AIM2-like receptors, detect intracellular pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [21] [25]. This recognition triggers the assembly of a multi-protein complex termed the inflammasome, which serves as an activation platform for caspase-1 [21] [24].

The inflammasome typically contains three components: a sensor protein (e.g., NLRP3), an adaptor (ASC, also known as PYCARD), and an effector (caspase-1) [21]. NLRP3 inflammasome formation is considered a two-step process involving priming and activation [25]. The priming signal (often through TLR activation) upregulates transcription of inflammasome components and pro-IL-1β via NF-κB signaling. The activation signal then triggers oligomerization of the sensor protein, which recruits ASC through PYD-PYD interactions. ASC subsequently recruits pro-caspase-1 via CARD-CARD interactions, leading to its autocatalytic cleavage and activation [21] [25].

Active caspase-1 then cleaves two key substrates: the pro-inflammatory cytokines pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 into their mature, bioactive forms, and gasdermin D (GSDMD) at an aspartate residue in its central linker region [21] [24]. This cleavage liberates the N-terminal domain of GSDMD (GSDMD-NT), which auto-inhibits by the C-terminal domain [21]. GSDMD-NT subsequently oligomerizes and inserts into the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, forming pores with an inner diameter of 10-14 nm [21]. These pores facilitate the release of mature IL-1β and IL-18, disrupt ionic gradients, and ultimately lead to cell swelling and membrane rupture [21] [26]. Recent research has identified NINJ1 as a critical mediator of plasma membrane rupture during pyroptosis, although its precise mechanism remains under investigation [21].

The Non-Canonical Inflammasome Pathway

The non-canonical pathway bypasses certain inflammasome components and is initiated when intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria directly binds to and activates caspase-4/5 in humans or caspase-11 in mice [21] [24]. These inflammatory caspases directly cleave GSDMD, generating the pore-forming GSDMD-NT fragment and triggering pyroptosis [21]. While non-canonical caspases cannot directly process pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, they can indirectly promote cytokine maturation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, possibly through potassium efflux resulting from GSDMD pore formation [21] [24].

Alternative Pyroptosis Pathways

Emerging evidence reveals additional pathways to pyroptosis. Caspase-3, traditionally associated with apoptosis, can cleave gasdermin E (GSDME) in certain contexts, producing a pore-forming N-terminal fragment that induces pyroptosis [21] [24]. This pathway may become particularly relevant when apoptotic cells are not efficiently cleared. Furthermore, granzyme B from cytotoxic lymphocytes can cleave GSDME at the same site as caspase-3, while granzyme A can process GSDMB, providing immune-mediated routes to induce pyroptosis in target cells [21] [24].

Diagram 1: Molecular pathways of pyroptosis. The canonical pathway is triggered by PAMPs/DAMPs, while the non-canonical pathway is initiated by intracellular LPS. Alternative pathways involve other caspases and granzymes. All pathways converge on gasdermin-mediated pore formation.

From Destruction to Regeneration: The Signaling Transition

DAMPs as Bridge Signals

The transition from destructive pyroptosis to pro-regenerative signaling is largely mediated by the controlled release of intracellular contents, particularly damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [27] [5]. These molecules, released through GSDMD pores and subsequent membrane rupture, function as critical danger signals that recruit and activate immune cells to coordinate tissue repair [5].

Key DAMPs released during pyroptosis include:

- High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1): A nuclear DNA-binding protein that promotes inflammation and immune cell recruitment when released extracellularly [5].

- ATP: Acts as a chemotactic signal for immune cells, particularly through P2X7 receptor signaling [5].

- Extracellular DNA/RNA: Recognized by intracellular and extracellular PRRs to amplify immune responses [5].

- Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs): Molecular chaperones that can activate immune responses upon release [5].

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Serve as secondary messengers in inflammatory signaling [5].

- IL-1β and IL-18: The mature cytokines processed during pyroptosis directly promote inflammatory responses [21] [22].

These DAMPs are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on surrounding cells, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), activating intracellular signaling cascades such as NF-κB and MAPK pathways [5]. This signaling initiates the transcription of genes encoding inflammatory mediators, cytokines, and chemokines essential for coordinating the subsequent repair process [5].

The Macrophage Transition and Regenerative Inflammation

A pivotal event in the transition to regeneration is the phenotypic shift in macrophage populations at the injury site [27]. Initially, upon tissue damage, monocyte-derived macrophages infiltrate the area and adopt a pro-inflammatory (M1-like) phenotype, characterized by phagocytosis of cellular debris and pathogen clearance, and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines [27]. These early responders are crucial for creating a sterile environment for regeneration.

Following this initial phase, a remarkable in-situ macrophage transition occurs, converting the pro-inflammatory population into an anti-inflammatory/pro-regenerative (M2-like) phenotype [27]. This transition is essential for initiating true tissue repair, as these alternatively activated macrophages secrete a repertoire of growth factors and anti-inflammatory cytokines that support stem cell activity and tissue remodeling.

Key secretory products from pro-regenerative macrophages include:

- Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) [27]

- Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) [27]

- Growth differentiation factors (GDF3, GDF15) [27]

- Vascular endothelial growth factor-α (VEGF-α) [27]

- Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) [27]

- Interleukin-10 (IL-10) [27]

This coordinated shift in macrophage function establishes a microenvironment conducive to stem cell-mediated regeneration, illustrating how the inflammatory response initiated by pyroptosis is harnessed for constructive tissue repair.

Diagram 2: The inflammatory to regenerative cascade. Pyroptosis initiates DAMP release, driving immune recruitment and a macrophage transition that enables stem cell-mediated tissue repair.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Pyroptosis and Regeneration

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Research investigating the connection between pyroptosis and regenerative signaling employs multidisciplinary approaches spanning molecular biology, cell biology, and in vivo models. The following experimental protocols represent core methodologies in this field.

In Vitro Pyroptosis Induction and Assessment

Protocol: LPS + ATP-induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages

Cell Preparation: Culture primary mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) or human monocyte-derived macrophages in appropriate media. Alternatively, use macrophage cell lines (e.g., J774A.1, RAW264.7, or THP-1 cells differentiated with PMA).

Priming Signal: Treat cells with ultrapure LPS (100 ng/mL) for 3-4 hours to upregulate NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β expression through TLR4 activation [25].

Activation Signal: Add ATP (5 mM) to the culture medium for 30-60 minutes to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome via P2X7 receptor stimulation and potassium efflux [25].

Pyroptosis Assessment:

- Cell Viability: Measure by LDH release assay in supernatant [24].

- Membrane Integrity: Assess via propidium iodide (PI) or 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining, as these dyes enter through GSDMD pores [25].

- Caspase-1 Activation: Detect using FLICA caspase-1 assay or western blotting for cleaved caspase-1 (p20 subunit) [21].

- GSDMD Cleavage: Analyze by western blot for GSDMD-NT fragment [21] [24].

- Cytokine Release: Measure mature IL-1β and IL-18 in supernatant by ELISA [21].

In Vivo Models for Pyroptosis and Regeneration

Protocol: Muscle Injury Model to Assess Regenerative Inflammation

Animal Models: Utilize C57BL/6 mice (8-12 weeks old) or transgenic models with cell-type-specific knockouts of pyroptosis components (e.g., Gsdmd^-/-, Casp1^-/-, Nlrp3^-/-) [27].

Injury Induction:

Tissue Collection and Analysis:

- Harvest tissue at multiple timepoints (6h, 24h, 3d, 7d, 14d post-injury) to capture different phases of the response [27].

- Process tissues for histology, immunofluorescence, RNA/protein extraction, or single-cell RNA sequencing.

Histological Assessment:

- H&E Staining: Evaluate inflammatory cell infiltration, myofiber necrosis/regeneration, and overall tissue architecture.

- Immunofluorescence: Stain for pyroptosis markers (cleaved GSDMD, caspase-1 p20), macrophage subtypes (F4/80, CD68, iNOS for M1, CD206, Arg1 for M2), and stem cell markers (Pax7 for muscle satellite cells) [27].

- In Situ Hybridization: Localize specific mRNA transcripts of interest (e.g., Il1b, Il18, Gsdmd).

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Pyroptosis and Regeneration

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Inducers | Ultrapure LPS, Nigericin, ATP, Monosodium Urate crystals, Poly(dA:dT), Transfected DNA | Activate specific inflammasome pathways (NLRP3, AIM2) to induce pyroptosis |

| Inhibitors | VX-765 (Caspase-1 inhibitor), Disulfiram (GSDMD inhibitor), MCC950 (NLRP3 inhibitor), Necrosulfonamide (MLKL inhibitor) | Determine specific pathway involvement and therapeutic potential |

| Antibodies | Anti-cleaved GSDMD, Anti-caspase-1 p20, Anti-IL-1β, Anti-NLRP3, Anti-ASC | Detect inflammasome formation, caspase activation, and GSDMD cleavage via WB, IF, IHC |

| Cell Death Assays | Propidium Iodide, 7-AAD, LDH Release Assay, SYTOX Green | Measure plasma membrane permeability and cell lysis characteristic of pyroptosis |

| Cytokine Measurement | IL-1β ELISA, IL-18 ELISA, Luminex Multiplex Assays | Quantify inflammatory cytokine release from pyroptotic cells |

| Animal Models | Gsdmd^-/-, Casp1/11^-/-, Nlrp3^-/-, Cell-type specific knockout mice (LysM-Cre, CD11c-Cre) | Determine cell-type specific functions and in vivo relevance of pyroptosis pathways |

Research Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

The mechanistic understanding of the pyroptosis-regeneration axis opens promising therapeutic avenues for various pathological conditions. In infectious diseases, modulating pyroptosis may help balance pathogen clearance with excessive tissue damage [23]. In cardiovascular diseases, where NLRP3 activation and pyroptosis contribute to atherosclerosis, heart failure, and ischemic injury, therapeutic targeting of these pathways may reduce vascular inflammation and improve outcomes [22] [25]. In cancer, inducing pyroptosis in tumor cells represents a novel strategy to stimulate anti-tumor immunity and overcome treatment resistance [24].

Natural products and small molecules targeting pyroptosis components show particular promise. Compounds such as polyphenols, flavonoids, saponins, and alkaloids have demonstrated ability to inhibit inflammasome assembly or block gasdermin cleavage in preclinical models [22]. The development of more specific inhibitors targeting GSDMD pore formation or the macrophage transition process represents an active area of pharmaceutical research with potential applications across inflammatory, infectious, and degenerative diseases.

Future research directions should focus on elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms controlling the macrophage transition from pro-inflammatory to pro-regenerative states, identifying tissue-specific differences in pyroptosis signaling, and developing technologies to spatially and temporally control these processes for therapeutic benefit. As our understanding of the inflammatory cascade deepens, so too will our ability to harness its power for promoting tissue repair and regeneration in diverse clinical contexts.

The stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1)/CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) axis represents a fundamental biological pathway orchestrating stem cell mobilization, targeted homing, and functional integration in tissue regeneration. This chemotactic signaling system operates with precision across diverse pathological contexts, from ischemic organ injury to inflammatory disease states, by establishing biochemical gradients that guide CXCR4-expressing stem cells to sites of tissue damage. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis within the broader context of biochemical pathways in cell regeneration during infection research. We examine molecular mechanisms, regulatory frameworks, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic modulation strategies, presenting quantitative data and standardized protocols to facilitate research and drug development targeting this critical regenerative pathway.

The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis serves as a master regulator of stem cell trafficking in physiological and pathological conditions. SDF-1 (also known as CXCL12), a member of the CXC chemokine family, and its primary receptor CXCR4, a G-protein coupled receptor, collectively control stem cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival [28]. Under homeostatic conditions, this axis maintains stem cell populations within specialized bone marrow niches. However, during tissue injury or infection, dramatic shifts in SDF-1 expression create chemotactic gradients that direct stem cell mobilization to damaged tissues [5]. This targeted homing mechanism is particularly relevant in infection research, where regenerative processes must operate within inflamed microenvironments. The biochemical precision of this system—wherein stem cells essentially "follow" SDF-1 concentration gradients to injury sites—represents a remarkable evolutionary adaptation for tissue repair and offers promising therapeutic avenues for enhancing regenerative outcomes in infectious diseases.

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Core Ligand-Receptor Interactions

SDF-1 exists in multiple isoforms (SDF-1α, SDF-1β) derived from alternative splicing, with SDF-1α being the most extensively studied. The SDF1 gene contains a 267 bp coding region encoding an 89-amino acid polypeptide, with its N-terminus being critical for receptor binding and activation [28]. CXCR4 consists of 352 amino acids arranged in a characteristic seven-transmembrane domain structure common to G-protein coupled receptors [28]. Upon SDF-1 binding, CXCR4 undergoes conformational changes that trigger intracellular signaling cascades mediating diverse cellular responses.

The binding affinity and subsequent signaling output are modulated by several factors. The alternate receptor CXCR7 functions as a scavenger receptor that creates SDF-1 gradients by sequestering the chemokine, thereby refining directional cues [29]. Additionally, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) proteolytically cleaves SDF-1, generating a truncated form with altered receptor binding properties and potentially antagonistic functions [30]. This enzymatic regulation adds a layer of temporal control to SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling dynamics.

Intracellular Signaling Cascades

SDF-1/CXCR4 engagement activates multiple parallel signaling pathways that collectively regulate stem cell behavior:

- G-Protein Mediated Signaling: CXCR4 coupling to Gαi proteins initiates phospholipase C (PLC) activation, leading to inositol trisphosphate (IP3)-mediated calcium release and diacylglycerol (DAG)-activated protein kinase C (PKC) signaling [28]. These events increase intracellular calcium concentration and activate transcriptional regulators.

- PI3K/Akt Pathway: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activation generates phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PIP3), recruiting Akt to the membrane where it becomes phosphorylated and activated. This pathway critically regulates cell survival, migration, and proliferation [31] [32].

- MAPK/ERK Pathway: The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, particularly extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), becomes activated following CXCR4 engagement, influencing cell cycle progression and differentiation decisions [31].

- JAK/STAT Pathway: Janus kinases (JAKs) and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) provide a more direct route from receptor engagement to transcriptional regulation, particularly for genes controlling inflammatory responses [28].

- NF-κB Activation: SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling induces nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) translocation to the nucleus, where it regulates genes involved in inflammation, cell survival, and immune responses [33].

Table 1: Key Signaling Pathways Activated by SDF-1/CXCR4 Axis

| Pathway | Key Components | Cellular Functions | Experimental Modulators |

|---|---|---|---|

| PI3K/Akt | PI3K, Akt, mTOR, FOXO | Cell survival, metabolism, migration | LY294002 (inhibitor) |

| MAPK/ERK | Ras, Raf, MEK, ERK | Proliferation, differentiation | U0126 (inhibitor) |

| Calcium Signaling | PLC, IP3, Ca2+ | Chemotaxis, secretion | U73122 (PLC inhibitor) |

| JAK/STAT | JAK2, STAT1/3 | Gene transcription, differentiation | Ruxolitinib (inhibitor) |

| NF-κB | IKK, IκB, NF-κB p65 | Inflammation, cell survival | BAY-11-7082 (inhibitor) |

Pathway Integration and Cross-Talk

The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis does not operate in isolation but integrates with other signaling systems to coordinate regenerative responses. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) directly regulates SDF-1 expression under low oxygen conditions, creating a molecular link between tissue ischemia and stem cell recruitment [28]. Similarly, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) influences CXCR4 expression, while matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-9, modify the extracellular environment to facilitate stem cell mobilization [34]. In infection contexts, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) can modulate SDF-1 production, creating interfaces between innate immunity and regenerative pathways [35].

Experimental Analysis of SDF-1/CXCR4-Mediated Homing

In Vitro Migration Assays

Transwell Migration Assay Protocol (Adapted from [31])

Objective: To quantify SDF-1-directed migration of stem cells in a controlled environment.

Materials:

- Transwell plates with porous membranes (5-8 μm pore size)

- Recombinant SDF-1α

- Serum-free basal medium

- Cell staining solution (e.g., crystal violet, calcein-AM)

- Fixation solution (4% paraformaldehyde)

Procedure:

- Prepare SDF-1 dilutions in serum-free medium at concentrations ranging from 0-200 ng/ml and add to lower chambers.

- Suspend stem cells (e.g., MSCs, hAD-MSCs) in serum-free medium at 1-5×10^5 cells/ml.

- Add cell suspension to upper chambers and incubate at 37°C for 4-6 hours.

- Remove non-migrated cells from upper membrane surface with cotton swab.

- Fix migrated cells on lower membrane surface with 4% PFA for 10 minutes.

- Stain with crystal violet for 20 minutes or calcein-AM for fluorescence quantification.

- Count migrated cells using microscopy or measure fluorescence intensity.

Applications: This assay demonstrated that SDF-1 induces dose-dependent migration of human amnion-derived MSCs (hAD-MSCs), with maximum effect at 100 ng/ml [31]. The PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitor LY294002 significantly reduced this migration, confirming pathway involvement.

In Vivo Homing Experiments

Stem Cell Tracking in Injury Models (Adapted from [31] [36])

Objective: To quantify homing of systemically administered stem cells to injured tissues.

Materials:

- Animal model of tissue injury (e.g., hepatic I/R, chemotherapy-induced POI)

- Fluorescently labeled stem cells (e.g., PKH26, CM-Dil, GFP)

- CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100

- ddPCR system for human DNA quantification in mouse tissues

- Immunohistochemistry reagents

Procedure:

- Establish injury model (e.g., hepatic ischemia/reperfusion or chemotherapy-induced ovarian insufficiency).

- Label stem cells with fluorescent marker according to manufacturer's protocol.

- Pre-treat experimental group with AMD3100 (CXCR4 antagonist) if testing axis specificity.

- Administer cells via intravenous injection (tail vein in rodents).

- Sacrifice animals at predetermined time points (e.g., 24, 48, 72 hours).

- Harvest target organs and process for:

- Fluorescence microscopy to visualize labeled cells

- DNA extraction and ddPCR for human DNA quantification in mouse tissues

- Immunohistochemistry for SDF-1 and CXCR4 localization

Applications: This approach revealed that SDF-1 pretreatment enhanced endometrial regenerative cell (ERC) engraftment in injured colon tissue and improved outcomes in experimental colitis [32]. Similarly, hypoxia-preconditioned CXCR4-high MSCs showed significantly improved homing to injured liver compared to control MSCs [36].

Table 2: Quantitative Homing Efficiency in Various Injury Models

| Injury Model | Cell Type | Intervention | Homing Enhancement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy-induced POI | hAD-MSCs | None | 3.2-fold increase in ovarian homing | [31] |

| Hepatic I/R Injury | BM-MSCs | Hypoxia preconditioning | 2.8-fold increase in liver homing | [36] |

| Experimental Colitis | ERCs | SDF-1 pretreatment | 4.1-fold increase in colon engraftment | [32] |

| Myocardial Infarction | BM-MSCs | CXCR4 overexpression | 3.5-fold increase in cardiac retention | [28] |

| Hindlimb Ischemia | EPCs | HIF-1α stabilization | 2.9-fold increase in ischemic tissue | [28] |

Modulation of Axis Activity

Hypoxia Preconditioning Protocol (Adapted from [36])

Objective: To enhance CXCR4 expression on stem cells through controlled hypoxia.

Procedure:

- Culture stem cells to 70-80% confluence in standard conditions.

- Place cells in hypoxia chamber with 1-3% O₂, 5% CO₂, and balance N₂.

- Maintain in hypoxia for 24-48 hours in serum-free medium.

- Analyze CXCR4 expression by flow cytometry or Western blot.

- Use preconditioned cells within 6 hours for transplantation experiments.

Results: Hypoxia preconditioning (1% O₂ for 24 hours) increased CXCR4 expression 3.5-fold in mesenchymal stem cells and enhanced their migration toward SDF-1 in vitro [36]. In vivo, hypoxia-preconditioned MSCs showed significantly improved homing to injured liver compared to control MSCs.

SDF-1 Pretreatment Protocol (Adapted from [32])

Objective: To prime stem cells for enhanced homing through SDF-1 exposure.

Procedure:

- Culture stem cells to 80% confluence.

- Treat with 50-100 ng/ml recombinant SDF-1 for 24-48 hours.

- Verify CXCR4 upregulation by flow cytometry.

- Harvest cells for transplantation using standard protocols.

Results: SDF-1 pretreatment increased CXCR4 expression on endometrial regenerative cells and enhanced their immunomodulatory effects in experimental colitis, with improved outcomes through macrophage polarization toward M2 phenotype and regulatory T cell induction [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SDF-1/CXCR4 Axis Investigation

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example Uses | Commercial Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SDF-1 | Chemoattractant for migration assays | In vitro chemotaxis, cell priming | PeproTech, R&D Systems |

| AMD3100 (Plerixafor) | CXCR4 antagonist | Axis inhibition controls | Sigma-Aldrich, MedChemExpress |

| Anti-CXCR4 Antibodies | Receptor detection/blocking | Flow cytometry, IHC, neutralization | Abcam, BioLegend, R&D Systems |

| Anti-SDF-1 Antibodies | Ligand detection/neutralization | ELISA, Western blot, IHC | Abcam, R&D Systems |

| LY294002 | PI3K/Akt pathway inhibitor | Signaling mechanism studies | Cayman Chemical, Tocris |

| U0126 | MEK/ERK pathway inhibitor | Signaling mechanism studies | Cell Signaling Technology |

| DPP4 Inhibitors | Modulate SDF-1 degradation | Study chemokine processing | Sitagliptin (Merck) |

| Transwell Systems | Migration assays | Quantify chemotaxis | Corning, Costar |

| Hypoxia Chambers | Cell preconditioning | Enhance CXCR4 expression | Billups-Rothenberg |

Regulatory Mechanisms and Pathological Contexts

Expression Regulation

SDF-1/CXCR4 expression is dynamically regulated by multiple physiological and pathological stimuli:

- Hypoxia: HIF-1α directly binds hypoxia response elements in the SDF-1 promoter, upregulating its transcription during ischemia [28]. This creates a targeted recruitment signal for stem cells to oxygen-deprived tissues.

- Inflammation: Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β) and bacterial components (LPS from P. gingivalis) increase SDF-1 production in fibroblasts and stromal cells [33].

- Tissue Damage: DAMPs released from necrotic cells, including HMGB1 and ATP, trigger SDF-1 upregulation through pattern recognition receptor activation [5].

- Enzymatic Processing: DPP4 cleaves SDF-1, generating a truncated form with altered receptor activation properties and potentially antagonistic functions [30].

Integration with Immune Responses

In infection contexts, the SDF-1/CXCR4 axis interfaces with immune processes in several ways:

- Leukocyte Recruitment: SDF-1 directly recruits T lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils to infection sites, bridging regenerative and immune responses [33].

- Macrophage Polarization: MSC recruitment via SDF-1/CXCR4 promotes M1-to-M2 macrophage transition, resolving inflammation and supporting tissue repair [35] [32].

- Lymphocyte Regulation: The axis influences T cell differentiation, particularly enhancing regulatory T cell populations that control excessive immune activation [32].

Therapeutic Applications and Experimental Considerations

Enhancing Therapeutic Efficacy

Several strategies have been developed to potentiate SDF-1/CXCR4-mediated homing for regenerative applications:

- Cell Preconditioning: Hypoxia or SDF-1 pretreatment consistently enhances CXCR4 expression and improves homing efficiency across multiple stem cell types and injury models [31] [36] [32].

- Pharmacologic Modulation: HIF-1α stabilizers (e.g., hydralazine) and DPP4 inhibitors enhance endogenous SDF-1 signaling, while AMD3100 can be used to precisely control the timing of stem cell mobilization [28] [30].

- Combination Therapies: Sequential administration of mobilizing agents followed by targeted recruitment represents a promising approach for enhancing regenerative outcomes.

Experimental Design Considerations

When investigating SDF-1/CXCR4 axis in infection and regeneration contexts:

- Model Selection: Choose injury models that appropriately reflect the infectious or inflammatory context being studied, considering that SDF-1 expression patterns vary significantly between different pathologies.

- Time Course Analysis: Include multiple time points as SDF-1 expression is dynamically regulated following injury, typically peaking within 24-72 hours.

- Dosage Optimization: For therapeutic applications, determine optimal cell numbers and administration routes through pilot studies, as excessive dosing can cause vascular obstruction [36].

- Axis Specificity Controls: Always include AMD3100 treatment groups to confirm SDF-1/CXCR4-specific effects versus non-specific recruitment mechanisms.

The SDF-1/CXCR4 axis represents a master regulatory system for stem cell trafficking with profound implications for regenerative medicine in infection contexts. Its ability to coordinate precise homing of stem cells to sites of tissue damage through finely tuned biochemical gradients exemplifies the sophistication of endogenous repair mechanisms. From a therapeutic perspective, strategies that enhance this natural homing process—through cell preconditioning, pharmacological modulation, or targeted delivery—hold significant promise for improving outcomes in infectious diseases with tissue damage components. Future research should focus on refining these approaches while maintaining the delicate balance between regenerative and immune processes that is essential for successful tissue repair in infected microenvironments. The integrated experimental framework presented herein provides a foundation for systematic investigation of this critical pathway across diverse research and therapeutic applications.

Toolkits for Intervention: Advanced Technologies to Modulate Regenerative Pathways