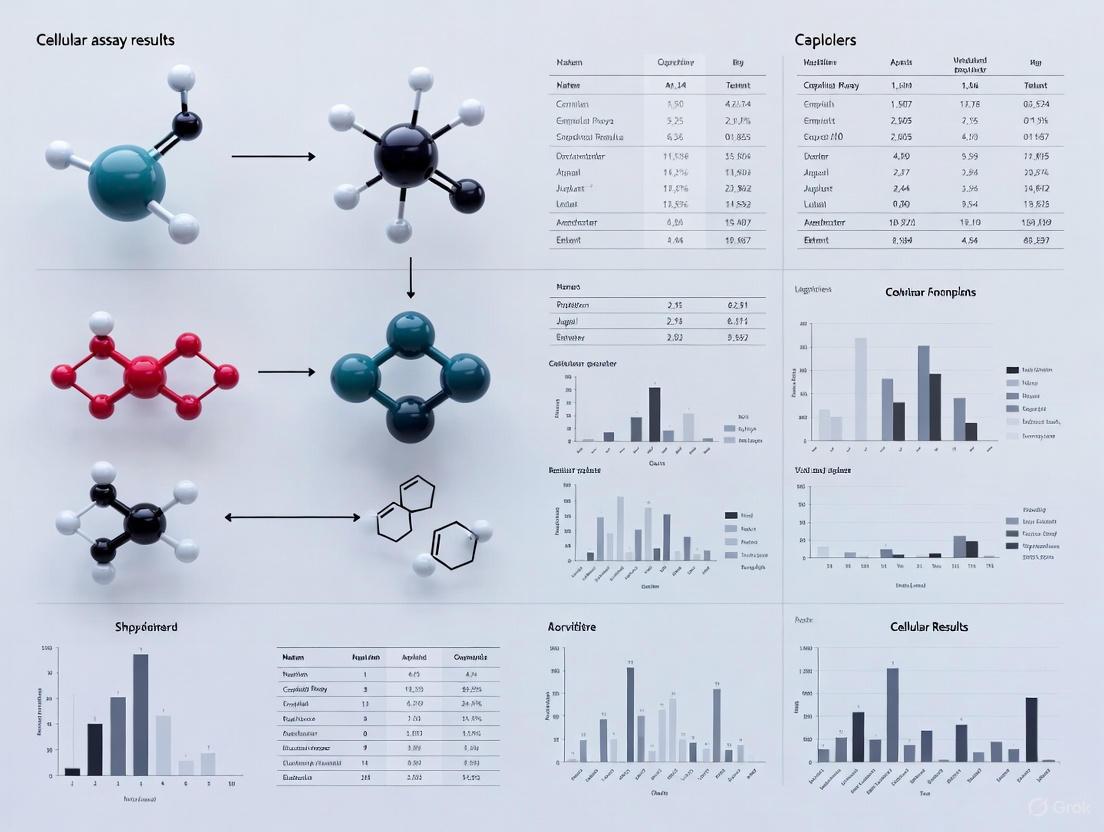

Bridging the Gap: A Strategic Guide to Resolving Discrepancies Between Biochemical and Cellular Assay Results

Inconsistencies between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) data are a major hurdle in drug discovery, often leading to delayed projects and misinterpreted structure-activity relationships.

Bridging the Gap: A Strategic Guide to Resolving Discrepancies Between Biochemical and Cellular Assay Results

Abstract

Inconsistencies between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) data are a major hurdle in drug discovery, often leading to delayed projects and misinterpreted structure-activity relationships. This article provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework to understand, troubleshoot, and resolve these discrepancies. We explore the foundational causes, from divergent physicochemical conditions to compound permeability, and present methodological strategies for optimizing assay design. The guide also covers advanced troubleshooting techniques and validation protocols to ensure data robustness, ultimately enabling more predictive in vitro models and efficient translation of hits into viable leads.

Understanding the Divide: Why Biochemical and Cellular Assay Results Diverge

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does "inconsistent BCA/CBA data" mean in drug discovery? Inconsistent BCA/CBA data refers to significant discrepancies between the results obtained from Biochemical Assays (BCA), which test drug candidates on isolated molecular targets, and Cell-Based Assays (CBA), which test candidates on living cells [1] [2]. A common example is when a compound shows high potency in a biochemical screen but fails to inhibit its target or demonstrate efficacy in a cellular environment [3]. These discrepancies can mislead research, wasting valuable time and resources.

2. Why is inconsistent data a critical problem? Inconsistent data directly impacts decision-making, leading to two major costly errors [1] [3]:

- Pursuing false leads: Advancing compounds that are only active in simple, non-physiological test conditions.

- Abandoning viable candidates: Discarding compounds that are active in complex cellular environments but appear inactive in initial biochemical screens.

3. What are the primary causes of these discrepancies? Several factors can cause BCA and CBA data to disagree:

- Cellular Permeability: The compound may not effectively enter the cell [3].

- Intracellular Metabolism: The compound might be modified or degraded inside the cell [3].

- Off-Target Effects: The compound interacts with unexpected cellular components, masking or altering its intended effect.

- Assay Design Artifacts: Some assay formats, particularly metabolism-based proliferation assays, can be influenced by changes in cell size or metabolic activity that are unrelated to cell number or target engagement [4] [5].

- Target Differences: The target's structure or conformation (e.g., dimerization state) in a living cell can differ from its purified form in a biochemical assay [3].

4. How can we troubleshoot a specific discrepancy between BCA and CBA results for a kinase inhibitor project? Follow this systematic troubleshooting guide:

| Troubleshooting Step | Description & Purpose | Key Reagents & Assays |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm Cellular Binding | Verify the inhibitor binds its intended target inside the cell. | NanoBRET Intracellular Target Engagement Assay [3] |

| 2. Measure Functional Output | Assess if target binding leads to the expected functional change (e.g., reduced phosphorylation). | Cellular Phosphorylation Assay [3] |

| 3. Check for Off-Target Effects | Determine if the compound causes unexpected phenotypic outcomes, like non-specific cytotoxicity. | BaF3 Cell Proliferation Assay; High-Content Imaging for cell cycle analysis [4] [3] |

| 4. Validate with an Orthogonal Assay | Use a different, direct method to confirm the key readout (e.g., direct cell counting vs. metabolic activity). | Image-Based Cell Counting (e.g., using DNA-binding dyes) [4] [5] |

5. Our ATP-based viability assay shows a weak effect, but the drug is supposed to be a potent cytotoxin. What could be wrong? This is a known pitfall. Metabolism-based assays like ATP luminescence (CellTiter-Glo) or MTS reduction measure metabolic activity, which is a proxy for cell number. However, some drug mechanisms can alter cellular metabolism, mitochondrial mass, or cell size without immediately killing the cell, leading to a significant underestimation of the drug's true potency and efficacy [4] [5]. For cytotoxic agents, especially those targeting DNA or the cell cycle, a direct cell counting method (e.g., high-content imaging) is recommended.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for investigating and resolving BCA/CBA discrepancies.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function & Application in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| NanoBRET Assay Kits | Measure target engagement (binding) of your compound to its protein target in the live, intact cellular environment, confirming cellular penetration [3]. |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Used in Western Blot or Cellular Phosphorylation Assays to detect changes in phosphorylation status of the target or its downstream substrates, confirming functional inhibition [3]. |

| BaF3 Proliferation Assays | Engineered cell lines used to investigate how kinase inhibition impacts cellular signaling pathways and proliferation in a controlled setting [3]. |

| DNA-Binding Dyes (e.g., for CyQUANT) | Enable direct quantification of cell number through fluorescence, bypassing potential confounders of metabolic assays [4] [5]. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Provide direct, image-based quantification of absolute cell number and cell cycle phase distribution, avoiding artifacts of indirect viability assays [4] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Interpretation

Protocol 1: Image-Based Cell Cycle Assay to Challenge Metabolism-Based Viability Assays

This protocol is designed to directly identify discrepancies between metabolic proxy assays and actual cell number [4] [5].

- Objective: To determine the true antiproliferative potency and mechanism of action of a compound by directly counting cells and analyzing their cell cycle phase, and to compare this data to results from ATP-based (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) and tetrazolium-reduction-based (e.g., MTS) assays.

- Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed adherent or suspension cells in 384-well plates. Allow cells to attach overnight.

- Compound Treatment: Treat cells with a dose-response series of the test compound. Include DMSO as a vehicle control.

- Staining and Imaging: After a defined incubation period (e.g., 48-72 hours), add a no-wash, DNA-binding fluorescent dye (e.g., Hoechst stain) to the cells. Incubate and then image the entire well using a high-content microscope.

- Data Acquisition: Use image analysis software to automatically identify nuclei and count cells. Simultaneously, measure the fluorescence intensity of each nucleus to determine DNA content and assign a cell cycle phase (G1, S, G2/M).

- Parallel Metabolic Assays: Run identical compound-treated plates in parallel using standard ATP-based luminescence and MTS reduction assays according to manufacturers' instructions.

- Expected Results & Interpretation:

- Agreement: All three assays show matching dose-response curves. This validates the use of simpler metabolic assays for compounds with this mechanism.

- Discrepancy: The image-based cell count shows a much steeper and more potent reduction in cell number than the ATP or MTS assays. This is common with DNA synthesis inhibitors (e.g., gemcitabine, etoposide) and indicates that the metabolic assays are underestimating the drug's true efficacy [4] [5]. The cell cycle data may also reveal a specific arrest phenotype (e.g., G2/M arrest for a microtubule inhibitor).

Quantitative Data Comparison: Assay Discrepancies with Different Drug Mechanisms

The table below summarizes hypothetical data illustrating how different assay formats can yield varying results for different drug classes.

| Drug & Proposed Mechanism | Image-Based Cell Count (IC₅₀ in nM) | ATP-Based Assay (IC₅₀ in nM) | MTS Reduction Assay (IC₅₀ in nM) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound A (Microtubule Inhibitor) | 10 nM | 15 nM | 18 nM | Good agreement; metabolic assays are a reliable proxy. |

| Compound B (DNA Synthesis Inhibitor) | 5 nM | >1000 nM | >1000 nM | Major discrepancy. Metabolic activity remains high despite reduced cell number, profoundly underestimating potency [4] [5]. |

| Compound C (Kinase Inhibitor causing cell cycle arrest) | 50 nM (cytostatic) | 200 nM (weak effect) | 250 nM (weak effect) | Metabolic assays show reduced sensitivity. Arrested cells remain metabolically active, masking the cytostatic effect. |

Diagram: Troubleshooting Pathway for BCA/CBA Discrepancies

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing the root cause of inconsistent data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is there often a discrepancy between the activity I measure in a simple biochemical assay and in a more complex cellular assay?

This is a common frustration in drug discovery. The discrepancy often arises because the physicochemical (PCh) conditions inside a living cell are vastly different from the simplified environment of a standard biochemical assay (e.g., in a test tube or well plate) [6]. Your compound's activity can be influenced by:

- Solubility & Permeability: The compound must be soluble in the aqueous environment and permeable enough to cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target [6] [7].

- Specificity: Off-target binding or interactions with cellular components like transporters can alter the apparent activity in a cellular context [6].

- Assay Conditions: Standard buffers like PBS mimic extracellular fluid, not the crowded, viscous, and differentially salted intracellular environment, which can affect binding affinity (Kd) [6].

2. I've improved my drug candidate's solubility with a formulation, but its overall absorption didn't increase. Why?

This highlights a critical and often overlooked solubility-permeability interplay [8] [9] [10]. When you increase the apparent solubility of a drug, you may inadvertently decrease its ability to permeate the intestinal membrane. For example, using cyclodextrins to solubilize a drug can reduce the free fraction of the drug available for absorption [9] [10]. The overall absorption is a balance between these two key parameters; enhancing one at the expense of the other can lead to no net gain [8].

3. My laboratory keeps getting different results for the same sample. Is this always a sign of an error?

Not necessarily. Some variation is inherent to biological and analytical systems. It is helpful to calculate the Reference Change Value (RCV) to determine if the difference between two results is clinically significant [11]. The RCV accounts for both the analytical variation of the test method and the within-subject biological variation. If the difference is less than the RCV, it is likely due to these inherent random variations and not a laboratory error [11].

| Symptom | Common Culprits | Investigation Steps | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High potency in biochemical assays but low potency in cellular assays. | Poor Cellular Permeability: The compound cannot cross the cell membrane to reach the target [6]. | Perform a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) [12]. | Optimize the compound's lipophilicity (Log P); consider prodrug strategies [7]. |

| Intracellular Solubility Limits: The compound precipitates inside the cell or is trapped in cellular compartments [6]. | Measure the compound's solubility in a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer [6]. | Reformulate the compound using amorphous solid dispersions or lipid-based delivery systems [7]. | |

| Off-Target Binding/Specificity: The compound binds to non-target proteins or is degraded in the cellular milieu [6]. | Use techniques like isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to check for non-specific binding in crowded solutions [6]. | Redesign the compound for higher selectivity; check chemical stability in cellular lysates. | |

| Inconsistent results when the same compound is tested using different dispensing technologies. | Liquid Handling Inaccuracy/Imprecision: Systematic bias or random error in volume delivery can distort concentration-response curves [13]. | Model the error propagation using the bootstrap principle to identify which dispensing step contributes most to the variance [13]. | Switch to more precise dispensing technology (e.g., acoustic droplet ejection); regularly calibrate liquid handlers [13]. |

| Compound Adhesion: The compound sticks to the tips of liquid handlers, reducing the delivered concentration [13]. | Compare results using disposable tips versus washable tips. | Use low-binding tips or plates; include carrier proteins (e.g., BSA) in the buffer. | |

| Variable results for the same sample between labs or over time. | Pre-analytical Variation: Differences in patient diet, physical activity, or timing of sample collection [11]. | Audit the sample collection and handling protocols. | Standardize patient preparation and sample collection procedures [11]. |

| Analytical Variation: Differences in testing methods, equipment, or reagents [11] [14]. | Participate in external quality assessment (EQA) schemes and use internal quality controls [11] [15]. | Harmonize laboratory methods and instruments; calculate RCV to assess significance of serial results [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

1. Protocol: Combined Solubility and Permeability (PAMPA) Workflow This integrated protocol conserves sample and increases efficiency by using the filtrate from the solubility assay directly in the permeability assay [12].

- Materials: MultiScreen Solubility filter plate, PAMPA plate, universal buffer (pH 7.4), DMSO stock compound solution (10 mM), acetonitrile, UV-compatible 384-well plate.

- Method:

- Solubility Incubation: Add 285 µL of universal buffer to each well of the solubility plate. Add 15 µL of 10 mM DMSO stock. Incubate with shaking.

- Filtration: Filter the plate to remove precipitated solids.

- Solubility Quantification: Transfer 60 µL of the filtrate to a 384-well UV plate. Add 15 µL of acetonitrile. Measure concentration via UV/Vis spectroscopy.

- Permeability Assay: Transfer 150 µL of the same solubility filtrate to the donor compartment of the PAMPA plate. Proceed with the standard PAMPA protocol to determine the effective permeability (Pe).

- Key Benefit: This method ensures permeability is measured at the compound's limit of aqueous solubility, providing more reliable and reproducible data by avoiding issues with detection limits and membrane retention that occur at lower concentrations [12].

2. Data Summary: The Impact of Solubility-Enabling Formulations

| Formulation Approach | Effect on Solubility | Effect on Apparent Permeability | Overall Impact on Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclodextrins | Increases via inclusion complexes [9] [10] | Decreases due to reduced free fraction of the drug [9] [10] | Governed by a trade-off; may be increased, unchanged, or decreased [9] |

| Surfactants / Lipidic Formulations | Increases via micellar solubilization [9] | Can decrease membrane/aqueous partition coefficient [8] [9] | Can be unpredictable; must balance solubility gain with permeability loss [8] |

| Amorphous Solid Dispersions | Increases by stabilizing high-energy amorphous state [7] | Minimal direct effect, but must prevent precipitation in GI tract [7] | Can lead to significant bioavailability enhancement if crystallization is inhibited [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Relevance to Discrepancy Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| PAMPA Plate | A non-cell-based assay to predict passive, transcellular drug permeability [12]. | Diagnoses if low cellular activity is due to poor permeability [12]. |

| Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer | A buffer designed to replicate the intracellular environment (e.g., high K+, crowding agents, specific viscosity) [6]. | Bridges the gap between biochemical and cellular assay results by providing more physiologically relevant Kd values [6]. |

| Reference Change Value (RCV) | A statistical tool (calculated as RCV = √2 × Z × √(CVA² + CVI²)) to assess the significance of differences in serial lab results [11]. | Objectively determines if a variation between two results is significant or expected from random biological/analytical variation [11]. |

| Hot-Melt Extrusion / Spray Drying | Technologies to produce amorphous solid dispersions, enhancing drug solubility and bioavailability [7]. | Solubility-enabling formulation techniques that can help overcome limitations of low-solubility (BCS Class II/IV) drug candidates [7]. |

Visualizing the Solubility-Permeability Interplay

The following diagram illustrates the critical trade-off that must be managed during formulation development for poorly soluble drugs.

The Assay Environment Gap

A major source of discrepancy between biochemical and cellular assays is the difference in their respective physicochemical environments, as summarized below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my IC₅₀ or EC₅₀ values often differ between biochemical and cell-based assays?

It is common to observe discrepancies, often of several orders of magnitude, between values obtained from biochemical assays (with purified targets) and cell-based assays [16] [6]. The typical causes include:

- Membrane Permeability: The compound may be unable to cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target [16].

- Active Efflux: Cellular mechanisms may actively pump the compound out of the cell [16].

- Off-Target Effects: The compound may engage with other non-specific targets within the complex cellular environment, altering the measured activity [16].

- Divergent Physicochemical Conditions: The simplified environment of a test tube (e.g., using PBS buffer) does not replicate the crowded, viscous, and compositionally distinct interior of a cell, which can significantly alter binding affinity (Kd) and reaction kinetics [17] [6].

Q2: What is the single most significant difference between standard lab buffers and the intracellular milieu?

While differences in pH and temperature are important, the most critical and often overlooked factor is macromolecular crowding [18] [6]. The intracellular space is densely packed with proteins, nucleic acids, and organelles, occupying 30-40% of the total volume [18]. This crowding can slow diffusion rates by tenfold or more and profoundly influence molecular interactions, association rates, and the stability of biomolecules [18]. Standard dilute buffers like PBS completely lack this property.

Q3: How can I experimentally mimic the intracellular environment in an in vitro assay?

Researchers are increasingly developing cytoplasm-mimicking buffers [17] [6]. Key modifications to standard buffers include:

- Ionic Composition: Replacing high Na⁺ with high K⁺ to match the cytosolic ion profile [6].

- Molecular Crowding: Adding inert, water-soluble polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or Ficoll to simulate the crowded environment [6].

- Viscosity Modifiers: Using agents like glycerol to increase viscosity towards intracellular levels [6].

- Cosolvents: Including compounds that modulate the solution's lipophilicity to better represent the cytosol [6].

Troubleshooting Guide: Bridging the Assay Discrepancy Gap

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weaker activity in cellular assays than in biochemical assays | - Poor membrane permeability- Active efflux- Compound instability in cellular environment- Target engagement hindered by crowding | - Assess logP to evaluate permeability- Use efflux pump inhibitors (e.g., verapamil)- Check compound stability in cell lysate- Perform assays with cytoplasm-mimicking buffers [16] [6] |

| Unexpected cytotoxicity at concentrations near IC₅₀ | - Off-target effects in the complex cellular environment- Disruption of cellular membranes or organelles | - Conduct counter-screens against related targets- Evaluate cellular health markers (ATP levels, apoptosis) [19] |

| Irreproducible enzyme kinetics data | - Assay conditions too simplistic, lacking cytoplasmic factors- High sensitivity to minor temperature or pH shifts | - Transition to crowded assay buffers [17] [6]- Use a thermostated plate reader and validate buffer pH at assay temperature [20] |

Quantitative Comparison: Standard Buffer vs. Intracellular Environment

The table below summarizes key physicochemical parameters, highlighting why results from standard biochemical assays may not translate directly to a cellular context.

| Parameter | Standard Biochemical Assay (e.g., PBS) | Intracellular Environment (Cytosol) | Impact on Molecular Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macromolecular Crowding | Dilute, no crowding | 30-40% of volume occupied [18] | Increases association rates, can alter protein folding and stability [18] [6] |

| Viscosity | Low, similar to water | High, can slow diffusion 10-fold or more [18] | Retards molecular diffusion, affecting reaction rates [18] [6] |

| Predominant Cations | High Na⁺ (157 mM), Low K⁺ (4.5 mM) [6] | High K⁺ (140-150 mM), Low Na⁺ (~14 mM) [6] | Ion-specific effects on protein function and binding equilibria |

| pH | Typically 7.4 | Slightly more acidic, ~7.2 [21] | Affects protonation states of key residues in enzymes and ligands |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing | Reducing (high glutathione) [6] | Can affect disulfide bond formation and stability of redox-sensitive compounds |

| Solvent | Often organic solvents or pure aqueous | Aqueous, but with complex cosolvent effects [20] [6] | Alters solvation and hydrophobic interactions |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a Basic Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer for Biochemical Assays

This protocol provides a starting point for adapting biochemical assays to more physiologically relevant conditions [6].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| KCl | Replicates high intracellular K⁺ | 140-150 mM |

| NaCl | Replicates low intracellular Na⁺ | ~10 mM |

| HEPES or PIPES | pH buffering | 20-30 mM |

| PEG 8000 or Ficoll 70 | Macromolecular crowding agent | 5-20% w/v |

| Glycerol | Viscosity modifier | 5-10% v/v |

| DTT or TCEP | Reducing agent (use with caution) | 1-5 mM |

| MgCl₂ | Essential cofactor for many enzymes | 1-5 mM |

Methodology:

- Base Buffer: Prepare a base buffer (e.g., 20 mM HEPES) containing 140 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl₂. Adjust the pH to 7.2 at 37°C.

- Add Crowding Agent: Gradually dissolve the crowding polymer (e.g., PEG 8000) into the base buffer to achieve the desired concentration (e.g., 10% w/v). This process may require gentle stirring and time.

- Add Modifiers: Add glycerol to adjust viscosity and, if appropriate for your target and it does not cause denaturation, a reducing agent like DTT.

- Validate Assay Performance: Test the activity of your purified protein or enzyme in the new buffer system and compare it to data obtained in standard buffer. Be aware that high crowding can increase optical density and light scattering, which may interfere with spectroscopic assays.

Protocol 2: Utilizing a Resealed-Cell System to Model Pathogenic Conditions

This advanced technique allows for the direct introduction of pathogenic cytosol into a cellular system, creating a powerful disease model [22].

Workflow: Resealed-Cell Model System

Key Reagents:

- Streptolysin O (SLO): A pore-forming toxin that selectively permeabilizes the plasma membrane without severely damaging intracellular organelles [22].

- Pathogenic Cytosol: Cytosolic extract prepared from the tissue of interest, e.g., liver from diabetic (db/db) model mice [22].

- Transport Buffer (TB): An energy-regenerating system to support intracellular processes in semi-intact cells.

Methodology Summary:

- Permeabilization: Incubate HeLa cells with a low concentration of SLO (e.g., 0.13 µg/mL) on ice to allow pore formation [22].

- Cytosol Exchange: Wash away the endogenous cytosol and incubate the semi-intact cells with cytosol prepared from wild-type (WT) or diseased (e.g., db/db, denoted Db) mouse liver.

- Resealing: Induce pore closure by exposing the cells to a solution containing Ca²⁺, effectively resealing the plasma membrane and creating "WT" or "Db" model cells [22].

- Analysis: Use these resealed model cells to investigate various biological processes (e.g., endocytic transport, signal transduction) under defined cytosolic conditions, thereby identifying differences directly attributable to the pathogenic environment [22].

The Critical Role of Molecular Crowding, Viscosity, and Ionic Strength in Modulating Kd Values

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why do my measured Kd values often differ between purified biochemical assays and cellular assays?

This common discrepancy arises because standard biochemical assays are typically performed in simplified, dilute buffer solutions (like PBS), which do not replicate the complex intracellular environment [23]. The cell cytoplasm is densely packed with macromolecules (crowding), has a distinct ionic composition (high K+/low Na+), and exhibits higher viscosity than standard test tube conditions [23]. These physicochemical (PCh) parameters directly influence binding affinity. For example, in-cell Kd values have been shown to differ by up to 20-fold or more from values measured in standard biochemical buffers [23].

FAQ 2: How does molecular crowding specifically affect protein-ligand binding affinity?

Molecular crowding can affect binding affinity through two primary mechanisms:

- Excluded Volume Effect: The high concentration of macromolecules in the cytoplasm reduces the available space, which can favor associated states (protein-ligand complexes) over dissociated states, potentially increasing binding affinity [23] [24].

- Soft Interactions: The chemical properties of the crowding molecules themselves can lead to "soft," non-specific interactions (e.g., hydrophobic or polar contacts) with the protein or ligand. These interactions can modify the protein's hydration shell and either increase or decrease binding affinity, depending on the specific chemistry of the crowders and the binding partners [24]. The net effect is a balance between these steric and chemical forces.

FAQ 3: What is the practical impact of solvent viscosity on my binding assays?

Increasing solvent viscosity is generally detrimental to ligand binding [25] [26]. A more viscous environment slows down the diffusion of molecules, which can significantly retard the association rate (k~on~) between the protein and its ligand [24]. While the dissociation rate (k~off~) may also be affected, its response depends non-trivially on the size and chemical characteristics of the viscosity-modifying agent [24]. Overall, higher viscosity can lead to an increase in the observed K~d~ (lower apparent affinity), particularly if the binding reaction is diffusion-limited.

FAQ 4: How does ionic strength influence my Kd measurements?

The effect of ionic strength on binding affinity is not uniform and depends heavily on the nature of the binding interface [25] [26]. If the binding is primarily driven by electrostatic interactions (e.g., between a charged DNA backbone and a basic protein patch), increasing ionic strength can shield these charges and weaken binding. Conversely, for interactions dominated by hydrophobic effects, the influence of ionic strength may be minimal. Furthermore, the type of ions matters; intracellular conditions are characterized by high K+ (~140-150 mM) and low Na+ (~14 mM), which is the reverse of common buffers like PBS [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Discrepancy between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) results for a lead compound.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Non-physiological Buffer Conditions | Compare K~d~ measured in standard PBS buffer vs. a cytoplasm-mimetic buffer [23]. | Adopt a cytoplasm-mimetic buffer for all BcAs to better predict cellular activity [23]. |

| Macromolecular Crowding | Perform the BcA in the presence of crowding agents (e.g., PEG, dextran) at 100-300 g/L and re-measure K~d~ [24]. | Include crowding agents in secondary BcAs to assess their impact on affinity and stability [23] [24]. |

| Altered Solvent Viscosity | Measure binding kinetics (k~on~ and k~off~) in buffers with and without viscosity modifiers like glycerol or sucrose. | Ensure consistent viscosity across assay conditions if comparing data; account for slowed association rates [25] [24]. |

| Incorrect Ionic Composition | Determine K~d~ using a buffer with an intracellular-like ion composition (high K+/low Na+) [23]. | Replace standard PBS with a buffer that mirrors the cytoplasmic ionic environment for relevant targets [23]. |

Problem: High variability in Kd measurements for a hydrophobic ligand.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitation of Ligand | Visually inspect solutions for cloudiness or use dynamic light scattering. | Optimize the concentration of co-solvents like DMSO to maintain solubility without disrupting binding (typically <0.1-1%) [26]. |

| Non-Specific Binding | Include negative controls with mutated, non-binding protein sequences [27]. | Use a carrier protein (e.g., BSA) or modify buffer components to reduce non-specific adsorption to surfaces. |

| Cosolvent Interference | Titrate the cosolvent concentration while measuring a known K~d~ to find a stable window. | Finely tune DMSO/concentrations to maintain ligand solubility without negatively impacting binding interactions [26]. |

The table below summarizes the typical directional effects of key physicochemical parameters on the dissociation constant (K~d~), association rate (k~on~), and dissociation rate (k~off~).

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Physicochemical Parameters on Binding Affinity and Kinetics

| Parameter | Effect on K~d~ (Affinity) | Effect on k~on~ (Association) | Effect on k~off~ (Dissociation) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Crowding | Variable (See FAQ 2) [24] | Significantly decreased [24] | Variable (Chemistry-dependent) [24] | Crowder size, concentration, and chemical properties [24]. |

| Increased Viscosity | Generally increases (Lowers affinity) [25] [26] | Significantly decreased [24] | Can increase or decrease [24] | Size and chemical nature of viscosity-modifying agent [24]. |

| Increased Ionic Strength | Variable | Variable | Variable | Hydrophobicity of ligand/binding site; charge of interacting surfaces [25] [26]. |

| Increased Hydrophobicity | Determines extent of cosolvent/salt influence [25] [26] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Polarity of binding site and ligand; nature of cosolvents [25]. |

| Moderate Temp. Increase | Marginal effect [25] [26] | Not Specified | Not Specified | System-dependent; larger changes can denature proteins. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Kd under Macromolecular Crowding Conditions

This protocol outlines how to determine the dissociation constant using Fluorescence Anisotropy (or a similar technique) in the presence of crowding agents to mimic the intracellular density [24].

Workflow Diagram: Kd Measurement with Crowding Agents

Materials:

- Purified protein of interest

- Fluorescently-labeled ligand

- Crowding agents: Polyethylene glycol (PEG 1kDa or 8kDa), Dextran (20kDa), or Ficoll [24].

- Cytoplasm-mimetic buffer: 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl~2~ [23].

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer with polarization/anisotropy capability.

Step-by-Step Method:

- Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of the crowding agent in the cytoplasm-mimetic buffer. A typical working concentration range is 100-300 g/L to mimic cellular density [24].

- Protein Incubation: Dilute your purified protein into the crowding agent solution and the control buffer (without crowder). Allow the protein to equilibrate in the crowded environment for 15-30 minutes on ice.

- Ligand Titration: Prepare a series of samples containing a fixed, low concentration of the fluorescent ligand and a varying concentration of your protein. Perform this titration in both the crowded and control buffers. Keep the concentration of the crowding agent constant across all samples in the crowded set.

- Equilibration: Incubate all samples in the dark at the desired temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C) for a sufficient time to reach binding equilibrium. This may take longer than in dilute buffer due to reduced diffusion.

- Measurement: Measure the fluorescence anisotropy (or intensity, if using another method) for each sample.

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured anisotropy (or normalized signal) against the total protein concentration. Fit the data to a standard 1:1 binding isotherm model to extract the K~d~ value for both the crowded and control conditions. Compare the results.

Protocol 2: Determining Kd via Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

EMSA is a simple, fast, and cost-effective method to measure K~d~ for protein-DNA/RNA interactions, and can be adapted for crowded conditions [28] [29].

Workflow Diagram: Kd Determination via EMSA

Materials:

- Purified DNA-binding protein

- Target DNA fragment, fluorescently labeled for detection.

- Crowding agents (as in Protocol 1), if needed.

- Native PAGE gel electrophoresis system

- Imaging system capable of detecting the fluorescent label (e.g., a gel doc system).

Step-by-Step Method:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a series of binding reactions with a fixed, low concentration of labeled DNA (ideally below the expected K~d~) and increasing concentrations of your protein. Include reactions with and without crowding agents.

- Incubation: Allow the reactions to incubate to equilibrium at the appropriate temperature.

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load the reactions onto a pre-run native polyacrylamide gel. Run the gel under non-denaturing conditions at a low constant voltage (to prevent heating) until sufficient separation is achieved.

- Visualization: Image the gel to visualize the free DNA and the protein-DNA complex bands.

- Quantification: Use software like ImageJ to quantify the band intensities for the free DNA and the complex in each lane.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the fraction of DNA bound for each protein concentration: Fraction Bound = [Complex] / ([Free DNA] + [Complex]). Plot the fraction bound versus the total protein concentration. Fit the data to the following equation to extract the K~d~ [28]:

- Fraction Bound = [E]~total~ / ([E]~total~ + K~d~)

- (This equation assumes the protein concentration [E]~total~ is much greater than the DNA concentration).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Mimicking Cytoplasmic Environments

| Reagent | Function & Rationale | Example Uses & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PEG (Polyethylene Glycol) | A common, uncharged macromolecular crowder. Used to simulate the excluded volume effect of the cytosol. Available in various molecular weights (e.g., 1kDa, 8kDa) [24]. | Studying the effect of steric crowding on protein-ligand binding and complex formation at concentrations of 100-300 g/L [24]. |

| Dextran | A branched polysaccharide crowder. Provides a more complex and biologically relevant crowding environment compared to PEG [24]. | Used similarly to PEG at 100-300 g/L to investigate crowding effects; can reveal chemistry-dependent "soft interactions" [24]. |

| Cytoplasm-Mimetic Buffer | A buffer solution designed to replicate the intracellular ionic environment (high K+, low Na+), rather than extracellular conditions like PBS [23]. | Replacing PBS in biochemical assays for intracellular targets to provide more physiologically relevant K~d~ measurements. Example: 150 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM MgCl~2~ [23]. |

| Glycerol / Sucrose | Low molecular weight agents used to increase solvent viscosity. They help study the impact of slowed diffusion on binding kinetics [25] [24]. | Useful for probing whether a binding reaction is diffusion-limited. Effects can differ from macromolecular crowders. |

| FLUOR DE LYS / COLOR DE LYS | Commercial assay systems using modified substrates for detecting enzyme activity (e.g., deacetylases) in a format adaptable to crowded conditions [30]. | High-throughput screening of enzyme inhibitors or activators under various assay conditions. |

FAQs: Understanding Activity Value Gaps

FAQ 1: What is an Activity Value Gap in drug discovery? An Activity Value Gap refers to the significant and often puzzling discrepancy between the potency or efficacy of a compound measured in a simple biochemical assay (with a purified protein target) and its activity observed in a more complex cellular assay. These gaps can manifest as orders-of-magnitude differences in IC50 values or conflicting efficacy (Emax) results, potentially derailing structure-activity relationship (SAR) campaigns and leading to wasted resources on misleading compound optimization [23] [5].

FAQ 2: What are the primary causes of these gaps? The causes are multifactorial and can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Physicochemical (PCh) Discrepancies: Standard biochemical assay buffers (e.g., PBS) do not mimic the intracellular environment. Differences in macromolecular crowding, viscosity, ionic composition (high K+/low Na+ intracellularly vs. the reverse in PBS), and cosolvent content can dramatically alter protein-ligand binding affinity (Kd) and enzyme kinetics [23].

- Cellular Phenotypic "Switching": A compound's mechanism of action can cause changes in cellular physiology that confound proxy readouts. For instance, a drug that arrests the cell cycle may cause cells to increase in size and mitochondrial mass, leading to an increase in ATP content per cell. An ATP-based viability assay would then underestimate the drug's antiproliferative potency [5].

- Compound-Specific Issues: Poor membrane permeability, chemical instability within the cellular milieu, and low solubility can prevent a compound from reaching its intracellular target at the expected concentration [23] [31].

- Assay Design Limitations: Biochemical assays may not recapitulate the native state of a target protein or its functional interactions within a signaling network, leading to misleading results [32].

FAQ 3: How can I determine if my cellular assay readout is reliable? Cross-validate your primary assay with an orthogonal method. A key case study demonstrated that while ATP-based (CellTiter-Glo) and MTS-tetrazolium reduction assays profoundly underestimated the potency of DNA-targeting agents like etoposide and gemcitabine, a direct cell-counting method via high-content imaging provided an accurate measure of cell number and antiproliferative effect. If different assay technologies for the same phenotypic endpoint (e.g., viability) yield vastly different dose-response curves, your readout may be unreliable [5].

FAQ 4: Are there specific compound classes prone to causing gaps? Yes, compounds with certain mechanisms of action are particularly problematic:

- Cell Cycle Inhibitors: Drugs like gemcitabine (DNA synthesis inhibitor) and etoposide (topoisomerase inhibitor) are classic examples where ATP-based assays fail [5].

- Bispecific Antibodies (BsAbs): The complex mechanisms of BsAbs, such as T-cell engagers, require sophisticated cell-based assays that accurately model the interaction between effector and target cells. A simple binding assay may not predict functional activity [33].

- Compounds targeting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway: As shown in profiling case studies, correlating biochemical kinase data with cell-based pathway analysis is crucial for confirming selectivity and understanding true cellular activity [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing the Root Cause of a Discrepancy

| Observed Discrepancy | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| Weaker cellular activity than biochemical potency suggests. | Poor cellular permeability; compound instability; efflux transporters; target inaccessibility. | Measure cellular permeability (e.g., PAMPA, Caco-2); test compound stability in cell media; use a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) to confirm target engagement [35] [31]. |

| Stronger cellular activity than biochemical potency suggests. | Intracellular metabolism to a more active metabolite; multi-target synergistic effect; "off-target" activity driving the phenotype. | Incubate compound with cell lysates and analyze by LC-MS for metabolites; perform target deconvolution (e.g., CETSA, proteomic profiling) [35]. |

| Non-monotonic or "switching" dose-response curves in cellular assays. | Concentration-dependent changes in MoA; activation of alternative pathways; cytotoxicity at higher concentrations. | Employ high-content imaging to analyze multiple phenotypic endpoints (cell number, cycle phase, morphology) across the concentration range [5]. |

| Inconsistent SAR between biochemical and cellular data. | The assay buffer environment is altering compound affinity rankings. The primary cellular assay is a poor proxy for the intended phenotype. | Reformulate biochemical assays with a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer [23]. Implement an orthogonal, direct cellular readout (e.g., imaging instead of metabolic activity) [5]. |

Guide 2: A Protocol to Bridge Biochemical and Cellular Gaps Using Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffers

Objective: To determine if the physicochemical environment is a major contributor to an observed activity value gap by replicating biochemical assays under conditions that mimic the intracellular milieu.

Background: Standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) reflects extracellular conditions (high Na+, low K+), not the crowded, viscous, and high-K+ environment of the cytoplasm. This can lead to significant shifts in Kd values [23].

Methodology:

- Prepare Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer (CMB):

- Cations: 140-150 mM KCl, 10-14 mM NaCl.

- Crowding Agents: Add macromolecular crowders like Ficoll PM-70 (up to 100 g/L) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) to simulate volume exclusion.

- Viscosity Modifiers: Glycerol or sucrose can be used to adjust viscosity to near-cytoplasmic levels (~2-4 cP).

- pH Buffer: Use HEPES or another suitable buffer to maintain physiological cytosolic pH (~7.2).

- Note: The exact composition may require optimization for your specific protein target.

Run Parallel Biochemical Assays:

- Perform your standard biochemical assay (e.g., inhibition of enzyme activity) in parallel using both standard buffer (e.g., PBS) and the newly formulated CMB.

- Ensure all other conditions (temperature, enzyme concentration, incubation time) are identical.

Data Analysis:

- Determine IC50 or Kd values from both assay conditions.

- A significant change in potency in the CMB condition (typically a weakening of affinity) that brings it closer to the cellular IC50 suggests the physicochemical environment was a key factor in the gap [23].

Interpretation: Implementing CMB for primary biochemical screening can lead to a more predictive SAR, ensuring that compounds optimized in biochemical assays retain their activity in cells.

Guide 3: Protocol for Orthogonal Validation of Antiproliferative Activity

Objective: To accurately determine the antiproliferative potency and efficacy of a compound by moving beyond metabolic proxy assays.

Background: Metabolic assays like CellTiter-Glo (ATP) and MTS reduction can be grossly misled by drug-induced changes in cell size, mitochondrial content, and metabolic activity, rather than reporting true cell number [5].

Methodology:

- Treat Cells: Seed cells in a 384-well plate and treat with a dilution series of your test compound for the desired duration (e.g., 72 hours).

Perform Parallel Assays on the Same Plate:

- Metabolic Assay: Lyse cells and measure ATP content using CellTiter-Glo according to the manufacturer's protocol. Record luminescence.

- Direct Cell Counting: Following the luminescence read, fix the cells and stain nuclei with a fluorescent DNA dye (e.g., Hoechst 33342, or a dye from a kit like CyQUANT). Image the plate using a high-content imager and use automated analysis to count the number of nuclei per well.

Data Analysis:

- Generate dose-response curves for both "ATP per well" and "Cell Number per well."

- Calculate the IC50 and Emax (maximal % reduction) for both readouts.

- A significant difference, especially a much weaker potency/efficacy in the ATP readout, indicates a phenotypic gap. The cell count data should be considered the more accurate measure of antiproliferative effect [5].

Interpretation: For compounds targeting the cell cycle or metabolism, direct cell counting is essential for accurate potency assessment. Relying solely on ATP or MTS assays can lead to the advancement of false negatives or poorly optimized compounds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Technology | Function in Gap Resolution | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Agents (Ficoll, Dextran, BSA) | Mimics the macromolecular crowding of the cytoplasm in biochemical assays, which can modulate ligand binding affinity and enzyme kinetics [23]. | Different agents create different PCh environments; requires empirical testing. High concentrations can increase non-specific binding. |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) | A label-free method to confirm direct target engagement of a compound in a live cellular environment, bridging the gap between binding and functional activity [35]. | Can be coupled with Western blot (lower throughput) or mass spectrometry (proteome-wide). Requires a good antibody or MS setup. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Provides direct, multiplexed readouts of cell number, cell cycle phase, and morphology, avoiding the pitfalls of indirect metabolic proxy assays [5]. | Capital investment is significant. Data analysis requires bioinformatics support. |

| Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer (CMB) | A buffer system designed with high K+, crowding agents, and adjusted viscosity to better replicate the intracellular environment for in vitro biochemical assays [23]. | No standard recipe exists; formulation must be optimized for each target protein system. |

| Bispecific Antibody (BsAb) Assay Platforms | Specialized cell-based co-culture systems (e.g., combining T-cells and tumor cells) are essential to characterize the true functional activity of BsAbs, which cannot be captured by simple binding assays [33]. | Must carefully select effector and target cell lines relevant to the BsAb's mechanism of action. |

Signaling Pathways & Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Activity Value Gap Root Causes

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow

Mimicking the Cell: Designing Physiologically Relevant Biochemical Assays

A persistent challenge in drug discovery and biochemical research is the frequent discrepancy between results from purified biochemical assays (BcAs) and cellular assays (CBAs). It is common to find that the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values derived from CBAs are orders of magnitude higher than those measured in BcAs [6] [23]. While factors such as compound permeability and solubility are often blamed, a critical underlying issue is that standard assay buffers like Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) are designed to mimic the extracellular environment, not the intracellular milieu where most drug targets reside [17] [6]. This article provides a technical guide for designing and implementing cytoplasm-mimicking buffers to generate more physiologically relevant and predictive data.

FAQ: Understanding the Core Concept

Why is PBS unsuitable for studying intracellular targets? PBS closely approximates extracellular fluid, with high sodium (~157 mM) and low potassium (~4.5 mM) levels. In contrast, the cytoplasm is characterized by a reversed ratio, with high potassium (~140-150 mM), low sodium (~14 mM), and additional factors like macromolecular crowding and different viscosity that profoundly influence molecular interactions [6] [23].

What are the key physicochemical parameters of the cytoplasm that need to be mimicked? Designing a physiologically relevant buffer requires replicating these key intracellular conditions [17] [6]:

- Ionic Composition: High K⁺, low Na⁺, and specific levels of Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺.

- Macromolecular Crowding: The cytoplasm contains 300-400 mg/mL of macromolecules, which limits diffusion volume and increases the effective concentration of reactants [36].

- Viscosity: Cytoplasmic viscosity is significantly higher than water, affecting diffusion and reaction rates [37].

- pH: Cytosolic pH is typically maintained around 7.2-7.4 [38].

- Redox Potential: The cytosol is a reducing environment due to high glutathione levels [6] [23].

How much can in-cell affinity values differ from standard assay values? Direct measurements have shown that protein-ligand dissociation constants (Kd) measured inside living cells can differ by up to 20-fold or more from values obtained in standard dilute buffer solutions [6] [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low protein activity or stability | Buffer ionic composition (high Na⁺) is denaturing or incorrect. | Replace PBS with a high K⁺, low Na⁺ buffer. Adjust Mg²⁺ and Ca²⁺ to cytoplasmic levels. |

| Unusually slow reaction kinetics | Lack of macromolecular crowding, altering diffusion and collision rates. | Introduce crowding agents like PEG or Ficoll at concentrations that simulate the crowded cellular interior [36]. |

| Discrepancy between biochemical and cellular assay results | Biochemical assay conditions are too simplistic and do not reflect the intracellular environment. | Perform biochemical assays in a newly designed cytoplasm-mimicking buffer and compare results. |

| Protein precipitation or aggregation | Overly aggressive crowding conditions or incompatible cosolvents. | Titrate the concentration of crowding agents and ensure compatibility of all buffer components. |

| Inconsistent data across a pH range | Switching between different buffering agents at different pH points introduces buffer-specific artifacts [39]. | Use a universal buffer mixture that maintains a consistent composition across the entire desired pH range. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffers

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HEPES | Buffering agent to maintain pH ~7.2-7.4. | Good buffer capacity at physiological pH; negligible metal binding [39]. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Provides high K⁺ concentration to mimic the cytosol. | Adjust concentration to ~140-150 mM. |

| Macromolecular Crowders (PEG, Ficoll) | Simulate the volume exclusion and crowding effects of the cytoplasm. | Start at 50-100 mg/mL and titrate; high concentrations can increase viscosity dramatically [36]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Creates a reducing environment similar to the cytosol. | Can disrupt proteins reliant on disulfide bonds; use with caution [6] [23]. |

| Glycerol | Cosolvent to modulate solution lipophilicity and viscosity. | Can affect protein stability and ligand binding. |

| Universal Buffer (UB) Formulations | A mixture of buffers (e.g., HEPES, MES, Acetate) to maintain consistent composition over a broad pH range. | Prevents artifacts from changing buffer identity in pH-dependent studies [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: Formulating and Testing a Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer

Step-by-Step Guide to Buffer Preparation

This protocol outlines the formulation of a basic cytoplasm-mimicking buffer, adapted from recent research on universal buffers and intracellular reconstitution [39] [36].

1. Base Buffer Formulation (UB3 Formula) Prepare a universal buffer that maintains capacity across a wide pH range (2.0–8.2) with minimal metal binding:

- HEPES: 20 mM

- MES: 20 mM

- Sodium Acetate: 20 mM

- Dissolve in distilled water. Adjust to the desired pH (e.g., 7.2) using KOH or HCl.

2. Adjust Ionic Composition Modify the base buffer to reflect cytoplasmic ion levels:

- Add KCl to a final concentration of 140-150 mM.

- Ensure that the final Na⁺ concentration is low (~14 mM).

- Add MgCl₂ to ~1-2 mM, reflecting cytoplasmic levels of free Mg²⁺.

3. Introduce Macromolecular Crowding

- Add a crowding agent like polyethylene glycol (PEG 8000) or Ficoll 70.

- A starting concentration of 50-100 mg/mL is recommended to simulate cytoplasmic crowding [36].

- Note: Solutions will become visibly more viscous.

4. Validate Buffer Performance

- Comparative Assay: Perform the same protein-ligand binding or enzymatic activity assay in the new cytoplasm-mimicking buffer and in standard PBS or Tris buffer. Compare the Kd, IC₅₀, or reaction rates.

- Control for Viscosity: To distinguish crowding effects from simple viscosity effects, run a control with an inert viscosogen like sucrose.

Visualizing the Workflow and Buffer Design Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for designing a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer and troubleshooting assay discrepancies.

Buffer Design and Troubleshooting Workflow

The core relationship between cytoplasmic properties and their effects on molecular interactions is summarized below.

How Cytoplasmic Properties Influence Assay Results

Moving beyond traditional buffers like PBS to designed solutions that mimic the cytoplasmic environment is a critical step toward unifying biochemical and cellular data. By consciously controlling for ionic strength, molecular crowding, viscosity, and redox potential, researchers can generate more predictive and physiologically relevant data, ultimately accelerating the drug discovery process and improving the fidelity of in vitro models.

A common challenge in translational research is the discrepancy observed between results from simplified biochemical assays and more complex cellular systems. These inconsistencies often stem from a failure to replicate the native physicochemical environment of the cell. This guide details how to optimize three key parameters—macromolecular crowding, salt composition, and cosolvents—to bridge this gap, enhancing the physiological relevance and predictive power of your in vitro experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Macromolecular Crowding Agents

Q1: Why do my purified proteins show different kinetics and oligomerization states in a test tube compared to in a cellular lysate? A: This is a classic sign that your biochemical assay lacks macromolecular crowding. The interior of a cell is densely packed with macromolecules (80–400 mg/mL), a condition known as macromolecular crowding [40] [41]. This crowding exerts excluded volume effects, which can significantly enhance protein-protein interactions, stabilize native structures, and promote the formation of biomolecular condensates via phase separation [40]. Without these crowders, your assay occurs in a dilute, non-physiological environment.

Q2: My crowding agent is causing protein precipitation. What should I do? A: Precipitation often indicates that the type or concentration of the crowding agent is inappropriate for your specific protein.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Screen Different Crowders: Test crowders with different chemical properties (e.g., inert polysaccharides like Ficoll, proteins like BSA, or polyethylene glycols).

- Titrate Concentration: Systematically vary the concentration of the crowding agent. Start low (e.g., 5-10 mg/mL) and gradually increase while monitoring for aggregation.

- Check for Chemical Interactions: Ensure the crowder does not chemically interact with your protein of interest. Inert crowders are preferred to isolate purely physical (steric) effects.

Q3: How does cellular aging impact the relevance of my crowding experiments? A: Recent single-cell analyses in yeast have shown that physicochemical homeostasis breaks down with age. While macromolecular crowding remains relatively stable in early aging, its stability is a stronger predictor of cellular lifespan than its absolute level [41]. Furthermore, aged cells exhibit dramatic changes in organelle volume, leading to "organellar crowding" on a micrometer scale, which can impede molecular diffusion [41]. Therefore, the health and age of the cells from which lysates are derived can be a critical, and often overlooked, variable.

Salt Composition and Ionic Strength

Q4: Why does my enzymatic activity drop when I change buffer types, even at the same pH? A: The specific salt ions in your buffer can directly modulate enzyme activity. Different ions can stabilize or destabilize the enzyme's tertiary structure, directly interact with the active site, or influence the electrostatic shielding that affects substrate binding. Always report the specific buffer and salt used, not just the pH and concentration.

Q5: How do I systematically optimize ionic strength for my binding assay? A: Ionic strength influences electrostatic interactions between biomolecules. A systematic optimization is required to find the physiological sweet spot.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare a Stock Solution: Create a high-concentration salt solution (e.g., 2-4 M KCl or NaCl).

- Set Up a Dilution Series: Prepare a series of assay reactions that are identical except for the concentration of the salt. A typical range might be 0-300 mM.

- Measure Activity/Binding: Perform your assay (e.g., measure initial reaction velocity or binding affinity) for each condition.

- Analyze the Data: Plot the activity (e.g., Vmax or % binding) against the ionic strength to identify the optimal range.

Q6: My assay contains a detergent. Could it be interfering with the salt effects? A: Yes. Detergents and salts can have synergistic or antagonistic effects. Detergents can disrupt lipid rafts or protein complexes that are stabilized by specific ionic environments. If your buffer contains detergents, it is even more critical to co-optimize their type and concentration along with the salt composition.

Cosolvents

Q7: What is the primary mechanism by which a cosolvent increases the solubility of my hydrophobic drug compound? A: Cosolvents like ethanol, DMSO, or polyethylene glycol work primarily by reducing the water activity of the solution. This creates a more favorable environment for hydrophobic molecules to remain in solution, thereby increasing their apparent solubility, often in a logarithmic fashion with increasing cosolvent concentration [42].

Q8: I am developing a reverse osmosis membrane and the literature mentions "cosolvent-assisted interfacial polymerization." What is the mechanism? A: In this context, cosolvents play a dual role. They can directly promote interfacial vaporization (if they have a low boiling point) and/or increase the solubility of aqueous phase monomers (like M-phenylenediamine, MPD) in the organic phase. This indirectly promotes the polymerization reaction, allowing for precise regulation of the polyamide membrane's morphology and its resulting separation performance [43].

Q9: The cosolvent I added to improve solubility is killing my cells. What are the typical compatible concentration ranges? A: Cosolvent cytotoxicity is a major concern. The table below lists maximum compatible concentrations for common cosolvents in biochemical contexts, but cellular tolerance can be much lower. Always perform a dose-response viability test (e.g., using a WST-1 or MTT assay [44] [45]) for your specific cell line.

Table: Compatible Concentrations for Common Cosolvents and Detergents

| Substance | Typical Compatible Concentration in Biochemical Assays | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 1-10% (v/v) | Common pharmaceutical cosolvent; cellular tolerance varies widely [42]. |

| DMSO | 0.1-1% (v/v) | Universal solvent; can induce cellular differentiation at high concentrations. |

| Triton X-100 | 0.1% (v/v) | Non-ionic detergent; can lyse cells at higher concentrations. |

| SDS | 0.1% (w/v) | Ionic detergent; generally disruptive to cellular membranes. |

| Urea | 1-2 M | Denaturant; can be used at controlled concentrations as a crowding agent. |

| Glycerol | 10-20% (v/v) | Used for protein stabilization; high viscosity can slow kinetics. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Discrepancies Between Biochemical and Cellular Assay Results

Unexpected differences between biochemical and cellular data can stem from failures to mimic the intracellular environment. Use this flowchart to diagnose potential causes related to physicochemical parameters.

Guide 2: Step-by-Step Protocol for Optimizing Physicochemical Parameters

This protocol provides a systematic approach to incorporating and optimizing crowding, salts, and cosolvents in a biochemical assay.

Workflow: Physicochemical Assay Optimization

Detailed Steps:

- Establish a Baseline: Perform your standard biochemical assay (e.g., enzyme kinetics, protein binding) in a simple, low-ionic-strength buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). This is your non-physiological baseline.

- Optimize Salt Composition:

- Prepare a series of reactions where you titrate the concentration of a monovalent salt like KCl or NaCl (e.g., from 0 mM to 200 mM).

- Alternatively, test a more physiologically relevant buffer like PBS or a simulated intracellular cytosol buffer (containing K+, Mg2+).

- Measure the output (activity, binding). The goal is to find a concentration that enhances or stabilizes your activity without causing precipitation.

- Introduce Macromolecular Crowding Agents:

- Select an inert crowder like polyethylene glycol (PEG, various molecular weights) or Ficoll.

- Add the crowder to your optimized buffer from Step 2, titrating from 50 mg/mL up to 150 mg/mL.

- Re-measure your assay output. Crowding should ideally enhance binding or complex formation. Monitor for precipitation.

- Address Solubility Issues:

- If your target molecule precipitates upon adding salts or crowders, introduce a minimal amount of a biocompatible cosolvent.

- DMSO is a common choice; start at a low concentration (e.g., 0.5% v/v) and increase only as needed. Document the final concentration precisely.

- Validate and Iterate: Compare the kinetic parameters, binding affinities, or oligomeric states from your optimized in vitro condition with data from cellular assays (e.g., FRET, BLI, or imaging). Use the discrepancies to guide further iterative optimization of these parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Physicochemical Assay Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Macromolecular Crowders | Ficoll PM70, PEG 8000, Dextran, BSA | Mimic the excluded volume effect of the crowded cellular interior to stabilize proteins and promote native interactions [40]. |

| Salts for Ionic Strength | KCl, NaCl, MgCl₂, K-Glutamate | Modulate electrostatic interactions, shield charges, and mimic the ionic composition of specific cellular compartments [41]. |

| Physiological Buffers | PBS, HEPES, Simulated Cytosol Buffers | Provide a stable pH and a more biologically relevant ionic background than simple Tris buffers. |

| Biocompatible Cosolvents | DMSO, Ethanol, Glycerol, Propylene Glycol | Enhance solubility of hydrophobic compounds in aqueous assay buffers, preventing aggregation [42]. |

| Metabolic Activity Assays | WST-1, MTT | Assess cell viability and metabolic activity to control for cytotoxicity of tested compounds or cosolvents [44] [45]. |

| Detergents & Surfactants | Triton X-100, Tween-20, SDS | Solubilize membrane proteins or disrupt lipid bilayers; use with caution as they can cause assay interference [46]. |

For researchers focused on resolving discrepancies between biochemical and cellular assay results, selecting the appropriate detection method is a critical strategic decision. The choice between fluorescence, luminescence, and label-free techniques directly influences data quality, physiological relevance, and ultimately, the validity of experimental conclusions. This technical support center provides a foundational guide to these core technologies, offering troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to support robust assay development.

Core Detection Technologies: Principles and Comparison

Technology Fundamentals

Fluorescence Detection relies on fluorophores absorbing high-energy light (excitation) and subsequently emitting lower-energy light (emission) [47]. This process involves a finite excited-state lifetime (typically 1-10 nanoseconds) during which the fluorophore undergoes conformational changes and interacts with its molecular environment before emitting a photon [47]. The separation between excitation and emission wavelengths is known as the Stokes shift, which is fundamental for isolating emission photons from excitation background [47].

Luminescence Detection encompasses light emission from cold sources through chemical (chemiluminescence) or enzymatic (bioluminescence) reactions, without the need for an external excitation light source [48] [49]. In chemiluminescence, a substrate reacts to form an electronically excited state that emits light upon returning to the ground state [48]. In bioluminescence, an enzyme (e.g., luciferase) catalyzes the oxidation of a substrate (luciferin), generating photons [48]. Luminescence reactions are categorized as "flash" (bright signal lasting seconds) or "glow" (stable signal lasting minutes to hours) [49].

Label-Free Detection utilizes biosensors to monitor biomolecular interactions in real-time without the use of tags or labels. Techniques include Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), which measure changes in the refractive index or other physical properties at a sensor surface upon molecular binding, preserving the native conformation of biomolecules [50] [51].

Quantitative Comparison of Detection Methods

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each detection method to guide your selection process.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Detection Methodologies

| Feature | Fluorescence | Luminescence | Label-Free |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Light emission after excitation by external light source [47] | Light emission from a chemical/enzymatic reaction; no excitation light needed [48] [49] | Measurement of inherent molecular properties (e.g., mass, refractive index) [51] |

| Key Measured Parameters | Fluorescence Intensity, FRET, Anisotropy, Lifetime (FLIM) [47] | Luminescence Intensity (RLU), BRET Ratio [48] | Binding Kinetics (ka, kd), Affinity (KD), Concentration [50] |

| Typical Sensitivity | High (pM-nM) [52] | Very High (fM-pM); can detect <10 viable cells [53] [49] | Moderate to High (nM-pM range for SPR) [51] |

| Dynamic Range | ~3-4 logs [47] | >6-8 logs [49] | Varies by technique [51] |

| Key Advantage(s) | High spatial resolution, multiplexing capability, versatile assay formats [54] [47] | High sensitivity, low background, wide dynamic range, simple instrumentation [49] | Provides kinetic and affinity data, no label interference, studies native biomolecules [50] [51] |

| Key Limitation(s) | Autofluorescence, photobleaching, light scattering, requires transparent samples [54] | Signal can be short-lived (flash), may require reagent addition, often endpoint [49] | Lower throughput for some platforms, expensive instrumentation, can be insensitive to conformational changes [51] |

| Throughput | High (microplates, imaging) [47] | High (microplates) [49] | Moderate (SPR, BLI systems) [51] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful assay development relies on a foundation of high-quality, purpose-built reagents. The following table details key solutions used across these detection platforms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| FLAG-Tag Biosensors | Specialized biosensors for label-free capture and characterization of FLAG-tagged recombinant proteins [50]. | Lead identification/optimization, cell line development, quality control [50]. |

| D-Luciferin | A luciferin substrate that is oxidized by firefly luciferase (Fluc) in an ATP-dependent reaction to produce light [54] [48]. | Cell viability assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo), reporter gene assays, bioluminescence imaging [53]. |

| NanoLuc Luciferase | A small, engineered luciferase with high stability and brightness, using furimazine as a substrate [48]. | Highly sensitive reporter assays, protein-protein interaction studies via NanoBRET [48]. |

| AlamarBlue (Resazurin) | A cell-permeable blue dye that is reduced to pink, fluorescent resorufin in viable cells [53]. | Fluorescent or colorimetric viability and proliferation assays; allows kinetic monitoring [53]. |

| Luminol | A chemiluminescent substrate that, when oxidized by H2O2 in the presence of a catalyst (e.g., HRP), emits blue light [54] [48]. | Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL) for Western blots, ELISA, and detection of H2O2 [48]. |

| NAD(P)H | An endogenous fluorophore; its fluorescence lifetime and intensity change with metabolic state, enabling label-free metabolic sensing via FLIM [55]. | Monitoring cellular metabolism, identifying metabolic heterogeneity in cancer cells [55]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol: Cell Viability Assay Using Luminescence (CellTiter-Glo 2.0)

This homogeneous, "add-and-read" assay quantifies ATP present in metabolically active cells, which is directly proportional to the number of viable cells [53].

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HeLa or other relevant cells in a white, tissue culture-treated 96- or 384-well microplate. Incubate overnight under standard conditions (e.g., 37°C, 5% CO₂) to allow attachment and recovery [53].

- Experimental Treatment: Expose cells to test compounds, vehicles, and controls for the desired duration.

- Reagent Equilibration: Thaw the CellTiter-Glo 2.0 reagent and allow it to reach room temperature.

- Assay Procedure: Discard the old culture medium and replace it with fresh medium. Add a volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent equal to the volume of medium present in each well [53].

- Lysis and Signal Stabilization: Shake the microplate for 2 minutes at 200 rpm on an orbital shaker to induce cell lysis and mix the contents. Then, incubate the plate at room temperature for 10 minutes to stabilize the luminescent signal [53].

- Detection: Read the plate using a luminescence microplate reader with an integration time of 0.2 - 1.0 seconds per well [53].

Protocol: Protein-Protein Interaction Analysis Using Label-Free Biolayer Interferometry (BLI)

BLI is a powerful technique for characterizing the binding kinetics and affinity of biomolecular interactions in real-time without labels [50].

Detailed Methodology:

- Biosensor Selection: Choose appropriate biosensors (e.g., Anti-Human Fc Capture for antibodies, Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) [50].

- Instrument Setup: Hydrate the biosensors in buffer for at least 10 minutes before use. Dilute the interacting partners (Analyte and Ligand) in a suitable kinetic assay buffer.

- Assay Procedure (Kinetics Mode): The analysis consists of five steps performed in a microplate containing the samples:

- Step 1 - Baseline: Immerse the biosensor in buffer for 60 seconds to establish a stable baseline.

- Step 2 - Loading: Immerse the biosensor in a solution containing the ligand for 300 seconds to capture it onto the biosensor surface.

- Step 3 - Baseline 2: Return the biosensor to the buffer for 60-120 seconds to wash away unbound ligand and re-establish a stable baseline.

- Step 4 - Association: Immerse the biosensor in a solution containing the analyte for 300-600 seconds to monitor the binding association.

- Step 5 - Dissociation: Finally, immerse the biosensor in buffer for 300-600 seconds to monitor the dissociation of the bound complex.

- Data Analysis: Process the binding sensorgrams using the instrument's software to calculate kinetic rate constants (association rate kₐ, dissociation rate kd) and the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) [50].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Fluorescence Detection Troubleshooting

Table 3: Common Fluorescence Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal Intensity | 1. Fluorophore concentration too low.2. Low quantum yield of the probe.3. Incorrect filter set [56].4. Low numerical aperture (NA) objective [56]. | 1. Optimize probe concentration, check for quenching.2. Choose a "brighter" probe (high extinction coefficient x quantum yield) [47].3. Verify filter set matches fluorophore's excitation/emission spectra [56].4. Use the highest NA objective possible (intensity ∝ NA⁴ in epifluorescence) [56]. |

| High Background | 1. Autofluorescence from cells, media, or plates.2. Incomplete washing.3. Light leakage in the instrument.4. Non-specific binding of the probe. | 1. Use phenol-red free media, low-fluorescence plates, and red-shifted dyes [54].2. Optimize wash stringency and number of washes.3. Ensure microscope/detector housings are secure [56].4. Include blocking agents (e.g., BSA) and optimize probe concentration. |

| Photobleaching | 1. Excessive exposure to excitation light.2. Presence of reactive oxygen species. | 1. Reduce exposure time/intensity, use anti-fade mounting reagents.2. Consider using more photostable probes (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes). |

| Unclear/Blurred Image | 1. Dirty objectives or filters [56].2. Incorrect cover slip thickness.3. Sample degradation. | 1. Clean optics with appropriate solvents [56].2. Use correct cover slip thickness (e.g., 0.17 mm) and adjust correction collar if available [56].3. Check sample integrity and fixative. |

Luminescence Detection Troubleshooting

Table 4: Common Luminescence Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal (Glow Assay) | 1. Low cell number or enzyme activity.2. Depleted or inactive substrate.3. Improper reagent storage. | 1. Increase cell number or ensure reporter is expressed. Use CellTiter-Glo for viability [53].2. Use fresh substrate, ensure it's prepared correctly.3. Store reagents as recommended; avoid freeze-thaw cycles. |

| Rapid Signal Decay (Flash Assay) | 1. Signal measured after its peak.2. Inconsistent reagent injection. | 1. Use injectors on the reader and optimize the timing/delay between injection and reading.2. Ensure injectors are calibrated and functioning properly. |

| High Well-to-Well Variability | 1. Inconsistent cell seeding.2. Bubbles in wells during reading.3. Inconsistent reagent dispensing. | 1. Ensure homogeneous cell suspension during seeding.2. Centrifuge the plate briefly to remove bubbles before reading.3. Calibrate liquid dispensers. |

| Low Signal-to-Noise | 1. Contamination (e.g., microbial).2. Chemiluminescent contamination on plate surfaces. | 1. Use sterile technique and check for contamination.2. Wipe the bottom of the microplate clean before reading. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I choose a label-free method over fluorescence or luminescence? A1: Opt for label-free techniques like BLI or SPR when your primary goal is to obtain detailed kinetic and affinity data (kₐ, kd, KD) for biomolecular interactions, or when labeling is impractical, alters protein function, or is impossible [51]. It is ideal for studying interactions in their native state.

Q2: My biochemical (label-free) assay shows strong binding, but my cellular (fluorescence) assay shows no effect. Why? A2: This common discrepancy can arise from several factors:

- Cell Permeability: The compound may not enter the cell.

- Off-Target Effects: The cellular environment may contain competing factors not present in the purified system.

- Assay Context: The label-free assay measures direct binding, while the cellular assay measures a downstream functional outcome, which may be regulated by compensatory mechanisms [55].

- Label Interference: The fluorescence label itself might be interfering with the function or localization of the molecule in a cellular context.

Q3: How can I detect metabolic heterogeneity in cell populations without using labels? A3: Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) of endogenous metabolic co-factors like NAD(P)H is a powerful label-free method. The fluorescence lifetime of NAD(P)H shifts with the metabolic state of the cell, allowing you to identify and quantify metabolically distinct subpopulations without any staining [55].