Bridging the Divide: A Strategic Guide to Managing Intracellular vs. Extracellular Physicochemical Conditions in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical, yet often overlooked, differences between intracellular and extracellular physicochemical environments.

Bridging the Divide: A Strategic Guide to Managing Intracellular vs. Extracellular Physicochemical Conditions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

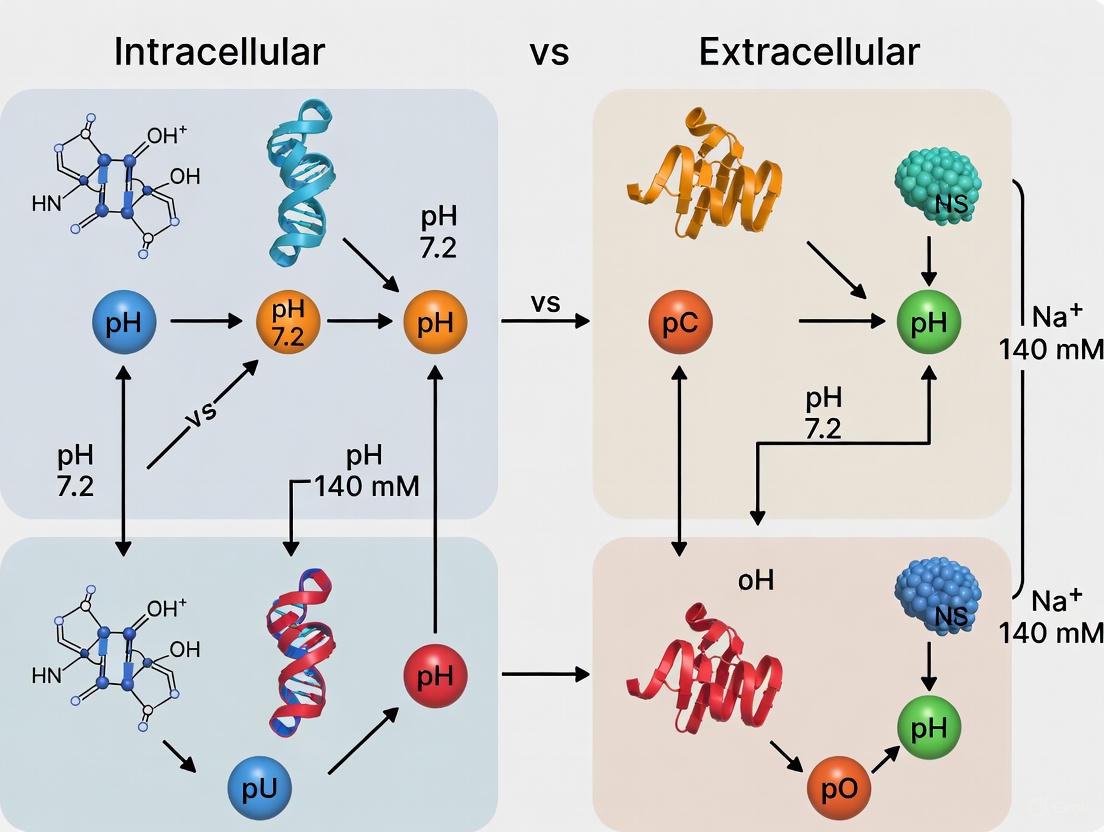

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical, yet often overlooked, differences between intracellular and extracellular physicochemical environments. It explores the foundational science behind these distinct conditions, presents methodological approaches for mimicking intracellular settings in vitro, offers troubleshooting strategies for common experimental discrepancies, and discusses validation techniques for translating findings from biochemical to cellular contexts. By synthesizing the latest research, this resource aims to bridge the gap between simplified assay conditions and complex biological reality, ultimately enhancing the predictive power and clinical relevance of preclinical research.

The Cellular Divide: Understanding Fundamental Intracellular vs. Extracellular Physicochemical Landscapes

Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the primary mechanism maintaining the K+/Na+ gradient? The sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+-ATPase) is the primary active transport mechanism. For every ATP molecule hydrolyzed, it exports three sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell and imports two potassium ions (K+) in, working against their concentration gradients [1].

- My cell viability is dropping; could ionic imbalance be the cause? Yes. Failure of the Na+/K+ pumps can lead to cell swelling and lysis. The pump helps control cell volume by maintaining internal osmolarity. When the cell swells, the change in internal ion concentrations can automatically activate the Na+/K+ pump to restore volume [1].

- Why is the K+/Na+ gradient critical for drug development? This gradient is fundamental to cellular physiology. It drives the activity of numerous secondary active transporters that move nutrients like glucose and amino acids into cells [1]. The gradient is essential for nerve impulse transmission and muscle contraction [2], and disruptions can impair fundamental processes like ribosome function and enzyme activity [3] [4].

- How do magnesium and calcium factor into this ionic landscape? Magnesium (Mg²⁺) is crucial for stabilizing DNA and RNA structures, is a cofactor for many enzymes, and forms the functional Mg-ATP complex [3]. Calcium (Ca²⁺) acts as a key second messenger in cell signaling [5]. Their intracellular and extracellular concentrations are also tightly regulated.

- How can I experimentally modulate this ionic environment in my cell cultures? You can use ion-specific transporters or channel inhibitors (e.g., ouabain for Na+/K+-ATPase) [1]. The ionic composition of the cell culture medium can be precisely adjusted. Additionally, ionophores can be used to make membranes permeable to specific ions.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Observed Cell Swelling and Decreased Viability

- Potential Cause: Compromised Na+/K+ pump activity, leading to osmotic imbalance.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Verify Pump Function: Assess Na+/K+-ATPase activity using a commercial assay kit. Check the expression levels of pump subunits via western blot.

- Check Energetics: The pump consumes substantial ATP [1]. Measure intracellular ATP levels. Ensure an adequate energy supply, as the pump is linked to glycolysis in some cell types [1].

- Review Media: Confirm that your culture medium contains adequate K+ and glucose concentrations to support pump function.

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results in Electrophysiology or Flux Studies

- Potential Cause: Unaccounted-for variability in intracellular ion concentrations or pump regulation.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Quantify Ions: Use precise methods like flame photometry or ICP-MS to directly measure intracellular K+ and Na+ levels in your samples [4].

- Control for Signaling: Be aware that the Na+/K+ pump can also function as a signal transducer, interacting with pathways like MAPK, which can be triggered by ligands binding to G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [1]. Control for these variables in your experimental design.

- Standardize Protocols: Ensure consistent cell passage numbers, confluence levels, and serum starvation times, as these can affect ionic homeostasis.

Problem 3: Unexpected Enzyme or Ribosomal Activity

- Potential Cause: Deviation from required ionic co-factor conditions.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Optimize Buffers: Ensure your reaction or lysis buffers contain the necessary monovalent (K+) and divalent (e.g., Mg²⁺) ions at correct concentrations. Note that K+ and Na+ can compete for binding sites on macromolecules like the ribosome [3].

- Chelate Cautiously: If using chelators like EDTA or EGTA, be mindful that they can remove essential divalent cations like Mg²⁺, which is critical for the function of many enzymes, ribosomes, and RNA structures [3].

The tables below summarize the core ionic differences and the energy-dependent mechanism that maintains them.

| Ion & Primary Role | Typical Intracellular Fluid (ICF) Concentration | Typical Extracellular Fluid (ECF) Concentration | Key Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium (K⁺)Major intracellular cation | 100–140 mM [1] / 5–15 mM [1] (Note: ICF K+ is typically high) | 3.5–5 mM [1] | Maintains resting membrane potential; essential for enzyme activity; regulates cellular osmolarity [6] [2]. |

| Sodium (Na⁺)Major extracellular cation | 5–15 mM [1] | 135–145 mM [1] | Generates action potentials; maintains blood pressure/volume; drives secondary active transport [6] [2]. |

| Magnesium (Mg²⁺)Critical enzymatic cofactor | Elevated amounts [6] | Lower amounts | Stabilizes DNA/RNA structures; essential for ATP-dependent enzymes; required for ribosome function [3]. |

| Calcium (Ca²⁺)Key signaling ion | Very low (~100 nM resting) | ~1–2 mM [5] | Acts as a second messenger; triggers exocytosis, muscle contraction, and apoptosis [5]. |

Table 1: Comparison of Major Ion Concentrations and Functions in Body Fluid Compartments. Concentrations are approximate and can vary by cell type. The high intracellular K+ and low Na+ are maintained by the Na+/K+ ATPase pump against a steep concentration gradient [6] [1].

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Ion Stoichiometry | 3 Na⁺ exported out / 2 K⁺ imported in per cycle [1]. |

| Energy Consumption | Consumes one ATP molecule per cycle [1]. Can account for 30-70% of a cell's ATP expenditure (up to 3/4 in neurons) [1]. |

| Electrogenic Effect | Net export of one positive charge per cycle, contributing to the negative interior of the cell membrane [1]. |

| Primary Inhibitors | Ouabain and other cardiac glycosides [1]. |

| Key Regulatory Factors | Upregulated by cAMP and associated signaling pathways; regulated by reversible phosphorylation and inositol pyrophosphates [1]. |

Table 2: Key Properties of the Sodium-Potassium Pump (Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase).

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Intracellular K⁺ and Na⁺ via Flame Photometry or ICP-MS

This protocol provides a method for directly quantifying intracellular ion content.

- Principle: Cells are harvested, washed free of extracellular ions, and digested. The ion content of the lysate is then measured against standard curves.

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Ice-cold Washing Buffer: 300 mM Sucrose, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl₂ (pH 7.4). The non-ionic sucrose maintains osmolarity without adding ions.

- Lysis/Digestion Solution: 1% (v/v) Ultrapure Nitric Acid or 0.5% (w/v) Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS).

- Workflow:

- Cell Harvesting: Grow cells to 80-90% confluence. Wash the monolayer twice with ice-cold washing buffer to remove all traces of culture medium.

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse the cells directly on the plate with a known volume of lysis/digestion solution. Scrape and transfer the lysate to a microcentrifuge tube. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the lysate at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove insoluble debris.

- Dilution: Dilute the supernatant appropriately with deionized water for analysis.

- Measurement: Analyze the samples using flame photometry or Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Compare readings to standard curves prepared from known concentrations of K⁺ and Na⁺.

- Normalization: Determine the protein content of a parallel, unlysed sample using a Bradford or BCA assay. Express ion concentrations as mmol/mg of protein.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Measuring Intracellular Ions.

Protocol 2: Assessing Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase Pump Activity

This protocol measures the hydrolytic activity of the pump by quantifying inorganic phosphate release.

- Principle: In a controlled assay buffer, the hydrolysis of ATP by the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase produces ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi). The Pi is quantified colorimetrically.

- Key Reagent Solutions:

- Assay Buffer (with ions): 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 130 mM NaCl, 20 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA.

- Assay Buffer (ion-free control): 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 130 mM Choline Chloride, 20 mM Choline Chloride, 3 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA. (Ouabain can also be used as a specific inhibitor control).

- ATP Solution: 5 mM ATP in assay buffer.

- Stop/Colorimetric Reagent: Malachite Green-based phosphate detection kit.

- Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a cell membrane fraction or use whole cells permeabilized with a low concentration of digitonin.

- Reaction Setup: Incubate samples in both the ion-containing and ion-free (or ouabain-containing) assay buffers for 5 minutes at 37°C.

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding the ATP solution. Incubate for 30-60 minutes at 37°C.

- Stop Reaction: Add the stop/colorimetric reagent to terminate the reaction.

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance at 620-660 nm after color development. The ouabain-sensitive or ion-dependent activity (difference between the two buffers) represents the specific Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase activity.

- Calculation: Calculate the Pi released using a standard curve and normalize to the protein content of the sample.

Diagram 2: Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase Activity Assay Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Ouabain | A specific, high-affinity inhibitor of the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase. Used to block pump activity in control experiments and to study pump-dependent signaling [1]. |

| Sucrose-based Washing Buffer | An iso-osmotic, ion-free solution used to wash cells before ion measurement, preventing efflux/influx of ions during the washing process. |

| Digitonin | A mild detergent used to selectively permeabilize the plasma membrane without disrupting intracellular organelles. Allows controlled access to the cytosol for introducing probes or substrates. |

| Flame Photometer / ICP-MS | Analytical instruments for precise quantification of elemental ion concentrations (K⁺, Na⁺, Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺) in biological samples [4]. |

| Malachite Green Phosphate Assay Kit | A colorimetric method for sensitive detection of inorganic phosphate (Pi), used to measure ATPase enzyme activity like that of the Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase. |

| cAMP Modulators (e.g., Forskolin) | Pharmacological agents used to increase intracellular cAMP levels, which upregulates Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase activity, allowing researchers to study its regulation [1]. |

| Ionophores (e.g., Nigericin) | Compounds that make lipid membranes permeable to specific ions (e.g., K⁺), used to experimentally collapse ion gradients. |

Key Signaling and Metabolic Pathways

The Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase is not just an ion pump; it is a nexus for cellular signaling.

Diagram 3: Na⁺/K⁺-ATPase Signal Transduction.

The Impact of Macromolecular Crowding and Cytoplasmic Viscosity on Molecular Interactions

FAQs: Macromolecular Crowding and Cytoplasmic Viscosity

1. What is macromolecular crowding and why is it important for in vitro experiments? Macromolecular crowding refers to the effects induced by a high total concentration of macromolecules (typically 100 g/L or higher) in a solution, which occupies a significant portion of the total volume [7]. The intracellular environment is densely packed, with macromolecules occupying 5–40% of the total cellular volume [8]. This is crucial for in vitro experiments because crowding strongly affects biochemical reactions by reducing the available solvent volume for other molecules. This excluded-volume effect can significantly alter thermodynamic activity, protein folding, molecular diffusion, and association rates compared to ideal, dilute buffer conditions typically used in labs [7] [8] [9]. Ignoring this can lead to a poor correlation between in vitro biochemical assay results and cellular activity [10].

2. How does cytoplasmic viscosity differ from bulk viscosity, and how does it affect molecular diffusion? The effective viscosity experienced by a molecule inside a cell depends on its size, unlike the macroscopic viscosity of a simple liquid. Smaller molecules experience a lower effective viscosity, while larger ones experience a viscosity closer to the macroscopic value of the cytoplasm [9]. This is described as length-scale dependent viscosity [9]. Consequently, the diffusion coefficient (D) of a molecule in the cytoplasm becomes dependent on its hydrodynamic radius (rp). For example, in HeLa cells, a probe with a radius much smaller than the characteristic crowding length scales (~5 nm) will diffuse more freely than a large protein complex, which will be severely hindered [9]. This relationship means the standard Stokes-Einstein equation, which assumes a uniform viscosity, often fails to accurately predict diffusion inside cells.

3. My in-cell NMR signals show protein destabilization, but crowding theory predicts stabilization. What could be the cause? While simple excluded volume models predict that crowding should stabilize more compact, native protein structures, experimental observations like yours are not uncommon. Atomistic simulations of a bacterial cytoplasm suggest that non-specific protein-protein interactions can sometimes destabilize native structures [11]. In these cases, favorable, shape-driven van der Waals interactions with other crowders can overcome the stabilizing excluded volume effect, leading to partial unfolding [11]. Therefore, the net effect of the cellular environment is a balance between excluded volume (which favors compaction) and weak, non-specific chemical interactions (which can favor compaction or destabilization).

4. How can I mimic intracellular crowding and viscosity in my test tube assays? To better approximate intracellular conditions, you can use crowding agents in your assay buffers. Common agents and their characteristics include:

- Dextran: A linear glucose polymer that increases both crowding and solution viscosity [7].

- Ficoll: A highly branched, synthetic sucrose polymer. It is often used to create a strong crowding effect with a relatively lower impact on solution viscosity compared to linear polymers of similar molecular weight [7] [9].

- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG): A flexible linear polymer frequently used in crowding studies. Its solutions have been used to model the length-scale dependent viscous response of the cytoplasm [9]. The choice of agent and its concentration should be tailored to the specific process under study, as different polymers can have varying effects on reaction rates and assembly processes [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Discrepancies Between Biochemical and Cellular Assay Results

Problem: The binding affinity (Kd) or activity of a compound measured in a purified in vitro system does not match the activity observed in subsequent cellular assays.

| Possible Cause | Experimental Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Neglect of Crowding Effects | Check: Compare your dilute buffer conditions (e.g., PBS) to intracellular estimates. Solution: Repeat the binding assay in a buffer containing crowding agents (e.g., 100-200 g/L Ficoll 70 or dextran) to see if the measured Kd shifts closer to the cellular value [10]. |

| Altered Molecular Diffusion | Check: Literature review on the diffusion coefficient of your target molecule in cells. Solution: If the reaction is diffusion-limited, the rate in cells will be slower. Consider that crowding can increase association rates for some proteins but decrease diffusion-limited reaction rates [8] [9]. |

| Non-Specific Interactions | Check: Test for compound aggregation or binding to other cellular macromolecules. Solution: The crowded environment increases the chance of weak, non-specific interactions, which can sequester your compound and reduce its effective concentration [11]. |

Step-by-Step Verification Protocol:

- Identify the Discrepancy: Quantify the difference between the in vitro IC50 and the cellular EC50.

- Replicate with Crowding: Perform the in vitro binding or activity assay using a buffer containing ~100 g/L of a crowding agent like Ficoll 70 or a mix of crowders to more closely mimic the cytoplasmic environment [7] [10].

- Check for Stability: Verify that your protein target and the compound are stable in the crowded buffer and do not precipitate.

- Analyze: Determine if the new Kd or IC50 measured under crowded conditions more accurately predicts the cellular activity.

Guide 2: Low Efficiency in Intracellular Delivery of Macromolecules

Problem: Low transfection efficiency or poor delivery of DNA, proteins, or other large molecules into cells for functional studies.

| Possible Cause | Experimental Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|

| Barrier of Crowded Cytoplasm | Check: Review the size of your macromolecule. Solution: The highly crowded cytoplasm significantly hinders the diffusion of large molecules [9]. Consider using smaller constructs or tags if possible. |

| Inefficient Delivery Method | Check: Evaluate the efficiency of your current transfection method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation). Solution: For difficult-to-transfect cells, investigate advanced physical methods. For example, coupling nanostraws with an electric field has been shown to significantly improve DNA transfection efficiency across various cell lines by directly penetrating the membrane and bypassing endocytosis [12]. |

| Cytoplasmic Viscosity | Check: The hydrodynamic radius of your delivered molecule. Solution: Be aware that once inside the cell, the effective cytoplasmic viscosity will slow down the movement of your molecule to its target site, which could delay the observable effect [9]. |

Table 1: Effects of Macromolecular Crowding on Biomolecular Processes

This table summarizes key quantitative findings on how crowding impacts various molecular properties and reactions.

| Process or Property | Change in Crowded Environment | Magnitude of Effect & Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Diffusion (in cells) | Decreased | Up to 10-100 fold reduction for GFP-sized proteins; effect is size-dependent [9]. | [8] [9] |

| Protein Association Rates | Increased | Up to 10-fold increase for protein-protein associations due to excluded volume effects [8]. | [8] |

| Protein Stability (Native State) | Variable | Can be increased (by ~kJ/mol) due to excluded volume or decreased due to non-specific interactions [11]. | [11] |

| Enzyme Activity | Variable | May increase or decrease; e.g., can promote structural changes that enhance activity (PGK) [11]. | [11] |

| Gene Expression | Altered | Crowding can enhance transcription factor binding and modulate expression levels [9]. | [9] |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Mimicking Intracellular Environments

A selection of common reagents used to study crowding effects in vitro.

| Research Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Example Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | Branched polymer crowder; provides strong excluded volume effect with relatively low viscosity increase. | Used at 50-200 g/L to mimic cytoplasmic crowding in protein folding and association studies [7]. |

| Dextran | Linear polymer crowder; increases both excluded volume and solution viscosity. | Used to study the separate effects of crowding and viscosity, e.g., in cellulose synthesis at 5-20% w/v [7]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Flexible linear polymer; used as a crowder and to model length-scale dependent viscosity. | Common in protein folding/precipitation studies; various molecular weights used (e.g., PEG 1000-8000) [9] [11]. |

| Cytomimetic Buffer | A buffer system incorporating crowders, metabolites, and ions to mimic cytoplasmic physicochemical conditions. | Used for in vitro assays to bridge the gap with cellular data; composition is actively researched [10]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Protein Diffusion in Crowded EnvironmentsIn Vitro

Objective: To quantify the reduction in the diffusion coefficient of a protein of interest in the presence of macromolecular crowders using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP).

Key Materials:

- Purified, fluorescently labeled protein.

- Crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll 70, dextran).

- Assay buffer.

- Confocal microscope with FRAP capability.

- Glass-bottom dish or chamber slides.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a solution of your fluorescent protein (e.g., 1 µM) in assay buffer.

- Prepare identical protein solutions containing various concentrations (e.g., 50, 100, 150 g/L) of your chosen crowding agent.

- Ensure all solutions are properly mixed and equilibrated to the experimental temperature.

- Data Acquisition:

- Place a droplet of the sample on the microscope stage.

- Select a region of interest (ROI) for photobleaching using a high-intensity laser pulse.

- Monitor the recovery of fluorescence into the bleached area over time.

- Perform multiple replicates for each condition.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the fluorescence recovery curves to an appropriate diffusion model to obtain the diffusion coefficient (D).

- Normalize the diffusion coefficient in crowded solutions (D) to that in buffer alone (D0).

- Plot D/D0 as a function of crowder concentration and probe size to characterize the crowding effect [9].

Protocol 2: Assessing Protein-Ligand Binding under Crowded Conditions

Objective: To determine the dissociation constant (Kd) of a protein-ligand interaction in the presence and absence of crowding agents.

Key Materials:

- Purified protein and ligand.

- Crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll 70).

- Equipment for binding measurement (e.g., Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), or fluorescence anisotropy).

Methodology:

- Buffer Preparation:

- Prepare a standard assay buffer.

- Prepare an identical buffer containing your chosen crowding agent (e.g., 100 g/L Ficoll 70).

- Binding Experiment:

- Perform your standard binding assay (e.g., ITC titration) using the protein and ligand in the standard buffer.

- Repeat the exact same experiment using the protein and ligand prepared in the crowding buffer.

- Crucially, ensure the crowder is present in all solutions (protein, ligand, and syringe) to avoid osmotic shock during the experiment.

- Data Analysis:

- For each experiment, fit the binding isotherm to obtain the Kd.

- Compare the Kd values from the crowded and non-crowded experiments.

- A change in Kd indicates that macromolecular crowding influences the binding thermodynamics, which may explain discrepancies with cellular assays [10].

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Crowding Effects on Molecular Processes

Diagram Title: Cellular Crowding Effects on Molecules

This diagram illustrates the major effects of macromolecular crowding on key biomolecular processes, highlighting the common discrepancies (in vitro vs. in vivo) that researchers must manage.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Assay Discrepancies

Diagram Title: Troubleshooting Assay Discrepancies Flowchart

This troubleshooting flowchart provides a logical pathway for diagnosing common causes of disparity between simplified in vitro experiments and results obtained in a cellular context.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate or Inconsistent Intracellular Redox Potential Measurements

- Problem: Reported redox potential values vary significantly between cell samples or do not align with expected physiological ranges.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Confirm Sensor Calibration: Ensure SERS nanosensors are calibrated for both redox potential and pH before each experiment, as pH influences redox measurements [13].

- Check for Chemical Interference: Review your cell culture medium composition. Certain components or metabolites can interfere with nanosensor function.

- Verify Specificity: Confirm that the nanosensors are specifically targeted to the cytosolic compartment and not localizing to organelles with different redox conditions.

Issue 2: Difficulty Maintaining Stable Physico-Chemical Conditions in Cell Culture

- Problem: The pH of the culture medium drifts during experiments, compromising the validity of measurements related to both pH and redox potential [14].

- Investigation & Solution:

- Inspect CO₂ Supply: For CO₂-bicarbonate buffered systems, ensure the incubator is maintaining a consistent 5% CO₂ atmosphere. Check for leaks or calibration drift in the CO₂ sensor [14].

- Assess Bicarbonate Levels: Confirm that the culture medium contains an adequate concentration of sodium bicarbonate for the CO₂ level used.

- Use pH Indicators: Utilize media containing phenol red as a visual pH indicator (yellow at pH < 6.8, purple at pH > 8.2) for a quick check of culture conditions [14].

- Control Temperature: Maintain culture temperature at 36°C to 37°C to prevent thermal shock and ensure normal cellular metabolism [14].

Issue 3: Low Signal or Poor Quality from SERS Nanosensors

- Problem: The signal obtained from the nanosensors is weak, leading to poor-quality data for redox and pH quantification.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Optimize Nanosensor Concentration: Titrate the concentration of nanosensors used for cell incubation to find the optimal balance between sufficient signal and minimal cellular disruption.

- Confirm Cellular Uptake: Use microscopy to verify that nanosensors are effectively internalized into the live cells of interest [13].

- Check Laser Alignment and Power: Ensure the Raman spectroscopy system is properly aligned and that laser power is optimized to obtain a strong signal without damaging the cells.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it essential to measure both redox potential and pH simultaneously in live cells? The intracellular redox potential is critically involved in cellular health and function, and its dysregulation is linked to numerous diseases. Crucially, redox potential is determined not only by the balance of oxidants and reductants but also by pH. Therefore, for a quantitative and accurate understanding, a technique that can multiplex both measurements is highly desirable [13].

Q2: What is the primary functional difference between intracellular and extracellular fluid? The primary difference lies in their location and composition. Intracellular fluid (ICF) is found inside cells and is the site of many biochemical reactions. Extracellular fluid (ECF) surrounds cells and is the medium for intercellular communication and transport [15] [16]. Their distinct compositions are maintained by the plasma membrane.

Q3: My research involves isolating a specific intracellular enzyme. Why must I carefully control the lysis buffer conditions? During cell lysis, the intracellular environment is exposed to artificial conditions. Using an inappropriate buffer pH or osmolarity can denature your target enzyme or activate proteases, drastically reducing yield and activity. The buffer must mimic key intracellular physico-chemical conditions to maintain enzyme stability and function.

Q4: What are some key indicators of poor physico-chemical control in my cell cultures? Key indicators include:

- Rapid color change of phenol red in the medium (indicating pH drift) [14].

- Changes in cell morphology or reduced viability/growth rates.

- High variability in experimental results between replicates, especially in sensitive assays like redox potential measurements.

Table 1: Characteristic Ion Concentrations in Body Fluid Compartments

Data derived from physiological compilations [16].

| Ion / Component | Intracellular Fluid (ICF) Concentration | Extracellular Fluid (ECF) Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na⁺) | Low | High |

| Potassium (K⁺) | High | Low |

| Chloride (Cl⁻) | Low | High |

| Bicarbonate | Low | High |

| Magnesium (Mg²⁺) | High | Low |

| Phosphate | High | Low |

| Proteins | High | Low (in interstitial fluid) |

Table 2: Typical Physico-Cultural Conditions for Mammalian Cell Lines

Standard in vitro culture parameters [14].

| Parameter | Typical Optimal Value/Range | Importance & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.4 | Critical for enzyme function and overall cell health; tightly regulated in vivo. |

| CO₂ | 5% | Standard atmospheric level used in conjunction with bicarbonate buffer to maintain physiological pH. |

| Temperature | 36°C to 37°C | Matches mammalian body temperature to support optimal growth and metabolism. Prevents thermal shock. |

| Osmolarity | ~290 mOsm/kg [16] | Must be controlled to prevent osmotic stress and water shift between intracellular and extracellular compartments. |

Experimental Protocol: Simultaneous Intracellular Redox and pH Measurement

Title: Multiplexed Measurement of Intracellular Redox Potential and pH in Live Single Cells Using SERS Nanosensors [13]

Objective: To quantitatively measure both redox potential and pH within the cytosol of live cells simultaneously.

Materials:

- SERS nanosensors functionalized for redox and pH response

- Appropriate mammalian cell line

- Standard cell culture equipment (CO₂ incubator, biosafety cabinet)

- Confocal Raman microscope (or similar SERS-capable system)

- Culture medium

Methodology:

- Sensor Preparation & Calibration: Calibrate the SERS nanosensors in solutions of known redox potential and pH to establish a standard curve for each parameter.

- Cell Preparation & Incubation: Culture cells according to standard protocols. Incubate the calibrated SERS nanosensors with the live cells to allow for cellular uptake and localization within the cytosol [13].

- Data Acquisition: Place the culture dish on the microscope stage. For single-cell analysis, locate a viable cell. Acquire SERS spectra from the nanosensors inside the cell. The spectral features (e.g., peak shifts or intensity ratios) will be specific to the local redox potential and pH [13].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the acquired SERS spectra against the pre-established calibration curves to derive quantitative values for both intracellular redox potential and pH simultaneously [13].

Conceptual and Workflow Diagrams

DOT Script: Cellular Ion Gradients

DOT Script: SERS Measurement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| SERS Nanosensors | Functionalized nanoparticles enabling multiplexed, quantitative measurement of intracellular parameters like redox potential and pH in live single cells through Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering [13]. |

| CO₂-Bicarbonate Buffer | A buffering system used in cell culture media to maintain a stable physiological pH (around 7.4) by balancing dissolved carbon dioxide and bicarbonate ions [14]. |

| Phenol Red | A pH indicator added to cell culture media; provides a visual cue for pH status (e.g., yellow at acidic pH, red at physiological pH, purple at basic pH) [14]. |

| Lysis Buffers | Solutions designed to disrupt cell membranes while preserving the native state of intracellular components (e.g., proteins, enzymes) by maintaining appropriate pH, osmolarity, and ionic strength. |

| Ionophores & Chemical Probes | Small molecules that can selectively transport ions across membranes or fluoresce in response to specific ions (e.g., Ca²⁺, H⁺), used to manipulate or measure ion gradients. |

Why Standard Buffers Like PBS Fail to Replicate the Intracellular Environment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main limitation of using PBS in biochemical assays? The primary limitation is that PBS does not mimic the complex intracellular environment. Biochemical assays performed in PBS measure activity under idealized, simple-salt conditions, which can differ significantly from the crowded, viscous, and compositionally distinct environment inside a cell. This often leads to discrepancies between biochemical data (e.g., binding affinity) and observed activity in cellular assays [10].

Q2: My drug compound shows high binding affinity in a PBS-based assay but low cellular activity. Could PBS be the cause? Yes, this is a common issue. The simplified conditions in PBS, including its specific ionic strength, pH, and lack of macromolecular crowding, can alter the true binding affinity (Kd) of a compound. The intracellular environment can change how both the drug and its target behave, leading to a mismatch between in vitro and cellular results [10].

Q3: Besides PBS, what other factors contribute to the gap between biochemical and cellular assay results? While the buffer is a key factor, other compound-specific properties are also often involved. These include the compound's cell permeability, solubility in a cellular context, specificity for the intended target, and metabolic stability inside the cell [10].

Q4: What are the key physicochemical parameters of the intracellular space that PBS fails to replicate? PBS is designed to mimic the osmolarity and ion concentrations of blood and other extracellular fluids, not the inside of a cell. The intracellular space, or cytoplasm, has a different profile in several key aspects [17] [10] [18]. The table below summarizes the fundamental differences.

Table 1: Key Differences Between PBS and the Intracellular Environment

| Physicochemical Parameter | Standard PBS | Intracellular Environment (Cytoplasm) |

|---|---|---|

| Macromolecular Crowding | Low | High |

| Viscosity | Low, water-like | High, gel-like |

| Ionic Composition | High Na+, Low K+ | Low Na+, High K+ |

| Redox Environment | Oxidizing | Reducing |

| Primary Role | Maintain pH and osmolarity outside the cell | Facilitate complex biochemical reactions inside the cell |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing PBS-Related Experimental Discrepancies

Problem: Inconsistency between biochemical binding data and cellular activity.

This guide will help you systematically determine if your buffer conditions are contributing to misleading results.

Step 1: Repeat the Experiment

- Unless cost or time prohibitive, first repeat the biochemical assay to rule out simple human error or technical mistakes [19].

Step 2: Validate with Appropriate Controls

- Introduce a positive control—a compound with known performance in both biochemical and cellular assays for your target. If it also shows a discrepancy, the assay conditions are likely a key variable [19].

Step 3: Evaluate Your Buffer System

- Question the Relevance: Ask if PBS is the right buffer for your experiment. Is your target located inside the cell? If so, a buffer that better mimics cytoplasmic conditions may be necessary [10].

- Check for Precipitation: Note that PBS will precipitate in the presence of divalent metals like zinc. If your assay involves such ions, PBS is unsuitable [20] [17].

Step 4: Systematically Change Variables

- If you suspect PBS is a problem, begin testing alternative buffers. Change only one variable at a time to clearly identify the cause of improvement [19]. For example, compare results in PBS against a buffer with:

- High K+ / Low Na+ concentrations.

- Macromolecular crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll, PEG).

- A reducing agent to mimic the intracellular redox state.

- If you suspect PBS is a problem, begin testing alternative buffers. Change only one variable at a time to clearly identify the cause of improvement [19]. For example, compare results in PBS against a buffer with:

Step 5: Document Everything

- Keep detailed notes on the exact buffer compositions, pH, and results for each experiment. This is crucial for reproducing successful conditions and understanding the influence of each parameter [19].

The following diagram illustrates this troubleshooting workflow.

Quantitative Comparison: PBS vs. Intracellular Conditions

To understand why PBS is a poor substitute for the intracellular environment, it is helpful to compare their specific ionic compositions. The table below details the standard formulation for 1X PBS and the estimated ionic concentrations in a typical mammalian cell.

Table 2: Ionic Composition of PBS vs. Typical Intracellular Conditions

| Component | Concentration in 1X PBS (mmol/L) | Concentration in PBS (g/L) | Estimated Typical Intracellular Concentration (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 157 [17] | - | ~5-15 (Low) |

| Cl- | 140 [17] | - | ~5-15 (Low) |

| K+ | 4.45 [17] | - | ~140 (High) |

| HPO42- | 10.1 [17] | - | Varies |

| H2PO4- | 1.76 [17] | - | Varies |

| NaCl | - | 8.0 [17] | - |

| KCl | - | 0.2 [17] | - |

| Na₂HPO₄ | - | 1.15 [17] | - |

| KH₂PO₄ | - | 0.2 [17] | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

When moving beyond standard PBS, consider these reagents and materials to create more physiologically relevant assay conditions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Intracellular Environment Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potassium-based Buffers | Used to create buffers with high K+ / low Na+ concentration, mirroring the cytoplasmic ionic balance rather than extracellular fluid like PBS. |

| Macromolecular Crowding Agents | Agents like Ficoll PM-70 or PEG are used to simulate the highly crowded interior of a cell, which can dramatically influence protein folding, binding affinity, and reaction rates. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) or TCEP | Reducing agents added to buffer systems to maintain a reducing environment similar to the cytoplasm, which is crucial for the stability of many proteins and biomolecules. |

| HEPES Buffer | A well-buffered substance for maintaining physiological pH in cell culture and biochemical experiments, often used as an alternative to phosphate buffers. |

| PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline) | A standard isotonic buffer for extracellular applications, such as washing cells, diluting substances, and transporting tissues. It is not suitable for mimicking intracellular conditions [20] [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Microinjection to Study Protein Conformation in Cells

This protocol, based on published research, details how to directly study protein behavior inside living cells, bypassing the limitations of external buffers [21].

Objective: To investigate the conformational changes of an intrinsically disordered protein (e.g., α-Synuclein) upon binding to intracellular membranes.

Background: In vitro experiments in PBS suggested the protein gains structure upon membrane binding, but in-cell studies failed to confirm this. This protocol uses microinjection and FRET to resolve this contradiction [21].

Workflow Diagram:

Materials:

- Purified protein of interest (e.g., α-Synuclein)

- FRET donor and acceptor dyes (e.g., Cy3 and Cy5)

- SH-SY5Y or other relevant cell line

- Microinjection system

- Confocal fluorescence microscope with FRET capability

- Cell culture reagents and labware

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation and Labeling:

- Purify the protein of interest and label it with a pair of FRET-compatible dyes.

- Confirm the labeling efficiency and protein function in vitro.

Cell Preparation and Microinjection:

- Culture cells on an appropriate imaging dish until they reach a suitable confluency.

- Using a microinjection system, inject a small volume of the labeled protein solution directly into the cytoplasm of the cells.

FRET Measurement and Analysis:

- Place the injected cells on a confocal microscope.

- Acquire FRET images over time to monitor the protein's behavior.

- Calculate FRET efficiency, which is inversely related to the distance between the two dyes, providing a measure of protein conformation.

Data Interpretation:

- Compare the FRET efficiency of the protein in the cytosol versus when bound to intracellular membranes.

- The identification of different FRET efficiencies confirms the existence of distinct conformational subensembles inside the living cell, a finding that simple buffer-based experiments could not reveal [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between Kd, Ki, and IC50?

Answer: Kd (Dissociation Constant) and Ki (Inhibition Constant) are both intrinsic affinity measures. The Kd describes the equilibrium between a ligand and its binding partner, while the Ki is a specific type of Kd for an enzyme inhibitor [22]. In contrast, IC50 (Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration) is a functional potency measure of the concentration needed to reduce a biological activity by half under specific experimental conditions [22] [23].

The key difference is that Kd and Ki are true constants reflecting binding affinity, whereas IC50 is an operational parameter that can be influenced by experimental conditions like enzyme and substrate concentrations [24] [22]. The following table summarizes their core differences:

| Parameter | Definition | Dependence on Conditions | Reports On |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kd | Dissociation constant for a ligand-receptor complex | Independent of concentration; an intrinsic property [23] | Binding Affinity |

| Ki | Dissociation constant for an enzyme-inhibitor complex | Independent of enzyme concentration (but may depend on substrate) [22] | Binding Affinity |

| IC50 | Concentration reducing activity to 50% | Highly dependent on enzyme and substrate concentrations, pH, temperature, etc. [24] [22] | Functional Potency |

2. Why do my IC50 values from biochemical assays differ from those in cellular assays?

Answer: Discrepancies between biochemical and cellular IC50 values are common and often stem from the vast differences in physicochemical conditions between simplified in vitro buffers and the complex intracellular environment [10]. Key factors include:

- Molecular Crowding & Viscosity: The crowded cellular interior can alter diffusion rates and binding equilibria [10].

- pH & Ionic Composition: The cytoplasmic pH and salt composition differ from common assay buffers like PBS, which can directly impact a compound's protonation state, solubility, and binding affinity (Kd) [10].

- Cellular Permeability & Efflux: In cells, the compound must cross membranes and avoid export pumps, which biochemical assays do not account for [22].

To bridge this gap, consider performing biochemical measurements under conditions that more accurately mimic the intracellular environment [10].

3. How does substrate concentration specifically affect my measured IC50?

Answer: The effect of substrate concentration on your IC50 is dictated by the mechanism of inhibition [22]. The relationship is mathematically defined for common mechanisms, as shown in the table below. Failure to account for this can lead to significant misinterpretation of inhibitor potency.

| Inhibition Mechanism | IC50 Relationship | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive | IC50 = Ki (1 + [S]/Km) [22] | IC50 increases as [S] increases. Use low [S] to find best potency. |

| Non-Competitive | IC50 = Ki [22] | IC50 is independent of [S]. |

| Uncompetitive | IC50 = Ki (1 + [S]/Km) | IC50 decreases as [S] increases. |

4. When can I approximate Kd from an IC50 value?

Answer: Approximating Kd from IC50 is only acceptable under a very narrow set of conditions [24]. According to exact mass action law calculations, the IC50 will be less than 20% larger than the Kd only if:

- The tracer/conjugate concentration is much smaller than the Kd.

- The receptor/enzyme concentration is much smaller than the Kd [24].

Otherwise, the two values can be vastly different. It is highly recommended to use specialized software packages to determine Kd values from experimental data for meaningful comparisons [24].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Results

Problem 1: Inconsistent Ki values derived from IC50 measurements.

- Potential Cause 1: Unaccounted enzyme concentration. In "tight-binding" inhibition, where the inhibitor affinity is very high (Ki is similar to or lower than the total enzyme concentration [E]T), the free inhibitor is depleted by binding to the enzyme. This causes the apparent IC50 to be higher than the true Ki [22].

- Solution: Apply a tight-binding correction to your data. The relationship is given by IC50 = Ki + [E]T/2, highlighting the direct dependence on enzyme concentration [23]. Ensure your experimental design uses enzyme concentrations well below the expected Ki.

- Potential Cause 2: Incorrect assumption of inhibition mechanism. Using the wrong equation (e.g., a competitive model for an uncompetitive inhibitor) to convert IC50 to Ki will yield an incorrect Ki value [22].

- Solution: Perform a full kinetic analysis (e.g., vary substrate and inhibitor concentrations) to rigorously determine the mechanism of inhibition before calculating Ki.

Problem 2: Poor correlation between compound affinity (Kd/Ki) and cellular activity.

- Potential Cause: Divergent physicochemical environments. The buffer used in your biochemical affinity assay (e.g., PBS) does not replicate the cytoplasmic environment, affecting the compound's true affinity in a cellular context [10]. Factors like pH, ionic strength, and molecular crowding can alter Kd values.

- Solution: Develop or use biochemical assay buffers that more closely mimic the intracellular milieu in terms of pH, salt composition, and crowding agents [10]. This helps minimize the physicochemical gap between assay types.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and their functions for studying binding and inhibition, with a focus on managing physicochemical conditions.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Defined Acidified Citrate Medium (D-ACM) [25] | An axenic culture medium that mimics the acidic (pH ~4.75) and nutrient-defined environment of the phagolysosome. Useful for studying pathogens or proteins that function in acidic intracellular compartments. |

| Buffer Systems for Cytoplasmic Mimicry [10] | Specially formulated buffers designed to replicate the cytoplasmic environment (e.g., specific pH, ionic strength, redox potential) for in vitro assays, helping to bridge the gap with cellular data. |

| Methyl-β-cyclodextrin [25] | Used in culture media to deliver hydrophobic nutrients or compounds, improving solubility and uptake in aqueous environments. |

| Octanol-Water Mixture | The standard two-phase solvent system for experimentally determining the partition coefficient (Log P), a key parameter of compound hydrophobicity [26]. |

| High Gelling Temperature Agarose [25] | Used for preparing solid growth media for fastidious organisms like Coxiella burnetii, allowing for colony formation under defined physicochemical conditions. |

Essential Experimental Workflows

Protocol 1: Converting IC50 to Ki for a Competitive Inhibitor

This protocol outlines the steps for accurately determining the inhibition constant (Ki) from a measured IC50 value under the assumption of competitive inhibition [22].

- Determine Km: Run a Michaelis-Menten experiment by measuring reaction initial velocities (v0) at a minimum of six different substrate concentrations ([S]). Plot v0 vs. [S] and fit the data to non-linear regression to determine the Km value for your substrate under your specific assay conditions.

- Measure IC50: Run an inhibitor dose-response experiment. Hold the substrate concentration ([S]) fixed and measure reaction velocity at a minimum of eight different inhibitor concentrations ([I]). Fit the data to a standard dose-response curve (e.g.,

Response = Bottom + (Top-Bottom)/(1 + 10^((LogIC50 - X)*HillSlope))) to determine the IC50. - Apply the Cheng-Prusoff Equation: Use the following equation to calculate Ki:

- Ki = IC50 / (1 + [S]/Km) [22]

- Report Conditions: Always report the experimental conditions used, including the specific [S] and the determined Km value, as these are critical for interpreting the Ki.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Cytoplasmic-Mimicry Buffer on Kd

This protocol compares the binding affinity (Kd) of a ligand measured in a standard buffer versus a buffer designed to mimic the cytoplasmic environment [10].

- Buffer Preparation:

- Prepare a standard assay buffer (e.g., PBS at pH 7.4).

- Prepare a cytoplasmic-mimicry buffer. While the exact composition may vary, it should consider factors like a specific pH (e.g., ~7.2), potassium as the major cation, and the potential inclusion of macromolecular crowding agents like Ficoll or bovine serum albumin.

- Binding Assay: Using a direct binding method (e.g., surface plasmon resonance, isothermal titration calorimetry, fluorescence anisotropy), perform a full titration of your ligand against its target.

- Parallel Measurement: Conduct the full binding experiment in both the standard buffer and the cytoplasmic-mimicry buffer, keeping all other variables (temperature, target concentration, etc.) constant.

- Data Analysis: Fit the binding data from each buffer condition to a suitable binding model (e.g., 1:1 binding) to extract the Kd value for each environment.

- Comparison: Compare the two Kd values. A significant difference indicates that the standard buffer may not accurately reflect the true affinity within a cell, highlighting the importance of physicochemical conditions.

Visualizing the Relationships: Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: IC50 to Ki Relationship Logic

Diagram 2: Biochemical vs. Cellular Assay Divide

From Theory to Bench: Practical Methods to Mimic and Manage Intracellular Conditions

A significant challenge in biochemical research is the frequent inconsistency between activity measurements from simplified in vitro assays and those from more complex cellular environments. This discrepancy can delay research progress and drug development [10]. While factors like compound permeability and stability are often blamed, a key reason is that standard biochemical buffers do not replicate the intricate physicochemical conditions of the living cell's cytoplasm [10]. This guide provides a framework for designing buffers that more accurately mimic the cytoplasmic environment, thereby bridging the gap between in vitro and cellular data.

FAQ: Fundamentals of Cytoplasmic Mimicry

1. Why is there a discrepancy between biochemical and cellular assay results?

The inconsistency in activity values (e.g., Kd) between simplified in vitro assays and cellular assays often arises because the intracellular physicochemical conditions are vastly different from those in standard biochemical buffers like PBS. Factors such as macromolecular crowding, cytoplasmic viscosity, specific ionic strength, and pH alter molecular interactions and equilibria [10]. Designing buffers that mimic the cytoplasmic environment helps minimize these discrepancies.

2. What are the key compositional differences between intracellular and extracellular fluids?

The chemical composition of body fluids is highly compartmentalized [16]. The table below summarizes the major differences.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Intracellular and Extracellular Fluid Composition

| Component | Intracellular Fluid | Extracellular Fluid |

|---|---|---|

| Cations | High K+, Mg2+ | High Na+ |

| Anions | High Phosphate, proteins | High Chloride, bicarbonate |

| Proteins | High concentration | Lower concentration (especially in interstitial fluid) |

| Origin | Cytoplasm of cells | Plasma and interstitial space |

3. What is macromolecular crowding and why is it important?

The cytoplasm is densely packed with macromolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, etc.) at concentrations estimated at 200–350 mg/ml, occupying a volume fraction of up to 40% [27]. This creates a crowded environment that generates an excluded volume effect, which favors association reactions and can shift conformational equilibria of proteins and nucleic acids [28]. This effect is largely absent in traditional dilute biochemical assays.

4. How do cosolvents differ from crowding agents?

Both are crucial components of the cellular milieu, but they function differently:

- Crowding Agents: These are high-molecular-weight, inert molecules (e.g., dextran, Ficoll) that act primarily through steric repulsion (excluded volume effect) [29] [28].

- Cosolvents: These are small, soluble molecules (e.g., TMAO, urea, glycerol) that affect biomolecular stability and reactions through direct chemical interactions (e.g., altering water structure) rather than simple volume exclusion [28]. They can be stabilizing (kosmotropes) or destabilizing (chaotropes).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffers

| Reagent | Function & Rationale | Example Uses & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dextran | A common polymeric crowding agent to mimic the excluded volume effect. Relatively inert and highly water-soluble [29]. | Used at high concentrations (e.g., 70-100 g/L) to simulate cellular crowding. Average molecular weight (e.g., 70 kDa) can be selected. |

| Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) | A kosmotropic cosolvent that stabilizes protein native states and counteracts denaturing stresses [29]. | Often used at 1 M concentrations to study its protective effects on protein structure and association reactions. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | To set the correct ionic strength and mirror the high K+ concentration found inside cells [16]. | Concentration must be optimized, but typically ranges from 100-150 mM for ionic strength mimicry. |

| Potassium Phosphate | Provides a buffering system while also contributing K+ ions and phosphate, both abundant intracellularly [16]. | pKa suitable for near-neutral pH. The potassium salt is preferred over sodium. |

| TRIS & HEPES | Common "Biological Buffers" or "Good Buffers" with defined pKa values for controlling pH [30]. | Select buffer based on desired pH (pKa ± 1). These buffers often have lower conductivity than inorganic alternatives. |

| ATP & Mg2+ | To replicate the energy-rich state of the cytoplasm and serve as cofactors for numerous enzymatic reactions [31]. | Mg2+ is often required to chelate ATP. Concentrations should reflect physiological levels (e.g., low mM range). |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Irreproducible binding kinetics or protein aggregation in the mimic buffer.

- Potential Cause 1: Inconsistent Buffer Preparation. The terms "phosphate buffer" or "borate buffer" are ambiguous and can lead to preparations with different ionic strengths and buffering capacities [30].

- Solution: Define the buffer recipe with "exquisite detail" in methods. Specify the exact salt (e.g., disodium hydrogen orthophosphate), the concentration, the agent and its molarity used for pH adjustment (e.g., "adjusted to pH 7.4 with 1M HCl"), and the temperature at which pH was measured [30].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate buffering capacity at the target pH. A buffer is only effective within one pH unit of its pKa [30].

- Solution: Select a buffering ion with a pKa value close to your desired cytoplasmic pH (typically ~7.2). Refer to Table 2 for common buffers and their pKa values.

Problem: The mimic buffer does not recapitulate the enhanced association rates observed in cells.

- Potential Cause: Lack of or insufficient macromolecular crowding. In dilute solutions, the entropic drive for biomolecules to associate is weaker [29] [28].

- Solution: Introduce high concentrations of inert crowding agents like dextran. For example, cell-like crowding conditions have been shown to increase the nucleation and association rates of actin polymerization by an order of magnitude [29]. Titrate the concentration of your crowding agent to find the optimal effect.

Problem: Protein misfolding or inactivation in the mimic buffer, despite correct ionic strength.

- Potential Cause: Missing stabilizing cosolvents. The cytoplasmic environment contains a complex mixture of osmolytes that help maintain protein stability [28].

- Solution: Include stabilizing cosolvents like TMAO (e.g., at 1 M) in your buffer formulation. TMAO is known to counteract the deleterious effects of denaturing stresses and can shift equilibria towards the oligomeric state of proteins [29].

Problem: Unusually high electrical current or overheating during electrophoretic techniques.

- Potential Cause: Buffer ionic strength is too high. While higher ionic strength can improve peak shape in techniques like capillary electrophoresis, it also increases current generation [30].

- Solution: Optimize the buffer strength as a compromise. It is recommended to adjust operating conditions to maintain current levels below 100 μA to prevent self-heating and method instability [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Quantitative Effects of Cosolvents and Crowding

The following table summarizes quantitative data on how different solution conditions can affect a specific biochemical process—the polymerization kinetics of actin. This serves as a model for how cytoplasmic conditions alter biomolecular reactions.

Table 3: Effects of Cosolvents and Crowding on Actin Polymerization Kinetics [29]

| Solution Condition | Effect on Association Rate Constant | Effect on Critical Concentration (cc) | Proposed Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 M TMAO (Kosmotrope) | Drastically increased | Not specified (decreased) | Shifts equilibria towards associated/oligomeric states; stabilizes interactions. |

| 1 M Urea (Chaotrope) | Decreased | Increased | Denatures proteins and perturbs favorable protein-protein interactions. |

| TMAO + Urea Mixture | Counteracts urea's effect | Counteracts urea's effect | TMAO offsets the denaturing effect of urea on both structure and interactions. |

| Dextran (Crowder) | Increased by one order of magnitude | Not specified (decreased) | Excluded volume effect favors association over dissociation. |

Detailed Protocol: Setting Up a Basic Cytomimic Buffer for Protein Studies

This protocol is adapted from principles used to create long-lived cell-free protein synthesis systems [31].

Base Buffer Preparation: Start with a buffer that mimics the intracellular ion profile. For example, prepare a solution containing:

- 100-150 mM KCl

- 10-50 mM Potassium Phosphate buffer, pH 7.2

- 1-5 mM MgCl2

- 1 mM ATP

pH Adjustment: Adjust the pH to 7.2 using a KOH solution. Critical step: Always measure the pH at the temperature the experiment will be conducted at, as pH is temperature-dependent [30].

Adding Crowding Agents: Dissolve a macromolecular crowder like dextran (average molecular weight 70 kDa) to a final concentration of 80-100 g/L. This will simulate the crowded cytoplasmic volume fraction [29].

Adding Cosolvents (Optional): Depending on the experimental question, add stabilizing cosolvents like TMAO (e.g., 0.5-1 M final concentration) to study their protective effects [29].

Final Buffer Validation: Filter sterilize the buffer if necessary. Avoid diluting a concentrated, pH-adjusted stock buffer, as this can lead to slight but significant pH shifts. Prepare the buffer at its final working concentration for best reproducibility [30].

Diagram Specifications

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key considerations for designing a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer.

Diagram Title: Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer Design Workflow

Advanced Techniques for Distinguishing Intracellular vs. Extracellular Compound Localization

Foundational Concepts: Intracellular vs. Extracellular Environments

FAQ: What is the fundamental difference between intracellular and extracellular localization?

The primary distinction lies in whether a compound, such as a protein, enzyme, or nanoparticle, is located inside the cell (intracellular) or outside the cell (extracellular). This localization is critically tied to function [32].

- Intracellular Compounds: Function within the cell's cytoplasm, nucleus, or organelles (e.g., mitochondria). They manage the cell's internal economy, including processes like glycolysis, DNA replication, and cellular respiration [32].

- Extracellular Compounds: Are synthesized inside the cell but are secreted to function outside. They act as external processors, breaking down external substrates (like food in the digestive tract) into simpler molecules for cellular uptake [32].

FAQ: Why is accurate determination of compound localization critical in drug development?

Incorrect localization can lead to complete therapeutic failure. For instance, the efficacy of nanoparticle-based photodynamic therapy can exhibit order-of-magnitude differences depending on whether the particles are inside or outside the target cancer cells. Precise intracellular localization is often paramount for eradicating malignancies and ensuring successful drug delivery [33].

Technique 1: Chiroptical Spectroscopy for Nanoparticle Localization

Troubleshooting Guide: My nanoparticle dimers do not show the expected chirality reversal upon cellular uptake. What could be wrong?

This technique exploits the unique chiroptical activity (circular dichroism in the visible range) of DNA-bridged plasmonic nanoparticle dimers. These dimers exhibit a spontaneous twisting motion around their DNA bridge, causing a measurable reversal of their circular dichroism (CD) peaks from negative to positive when moving from the extracellular fluid to the cytosol [33].

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No chirality reversal | The dimer structure is too rigid to reconfigure in the new environment. | Ensure dimers are not over-stabilized. Avoid coating with rigid polymers like PS-PAA, which impedes the twisting motion [33]. |

| Weak or noisy CD signal | Insufficient number of DNA bridges or low nanoparticle concentration. | Verify the number of DNA strands between nanoparticles does not exceed 1.6 ± 0.2 and optimize particle concentration [33]. |

| No cellular uptake | Nanoparticles lack a cell-penetrating mechanism. | Functionalize nanoparticles with cell-penetrating peptides (e.g., TAT, ~190 ligands per NP) to facilitate direct cytosolic penetration and avoid endosomal segregation [33]. |

Experimental Protocol: Monitoring Transmembrane Transport via CD Spectroscopy

- Dimer Assembly: Assemble dimers from slightly oblong Au NPs (e.g., 22 nm length) using a specific double-stranded DNA bridge (e.g., 5′-CAATAGCCCTTGGAT-3′ and its complement) to create a scissor-like geometry with inherent chirality [33].

- Surface Coating: Coat dimers with thiol-modified polyethylene glycol-5000 (SH-PEG-5000; ~860 molecules/NP) to reduce non-specific protein adsorption. Incorporate TAT peptides (~190 molecules/NP) to enable virus-like transmembrane transport [33].

- Cell Incubation & Measurement: Incubate dimers with mammalian cells (e.g., cervical cancer HeLa cells). Monitor the CD spectrum in the visible range (400-900 nm) in real-time. A reversal of CD peaks (e.g., from negative/positive to positive/negative at ~500/530 nm) indicates successful internalization from the interstitial fluid into the cytosol [33].

- Validation: Confirm intracellular localization using biological transmission electron microscopy (bio-TEM) or cryo-TEM tomography to visualize the reconfigured dimer geometry inside the cell [33].

Technique 2: Flow Cytometry for Surface and Intracellular Antigens

Troubleshooting Guide: I am getting high background noise in my intracellular staining. How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio?

Flow cytometry allows for the simultaneous analysis of cell surface markers (extracellular) and internal proteins (intracellular). Detecting intracellular targets requires fixation and permeabilization steps to allow antibodies access to the inside of the cell [34] [35].

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background | Non-specific antibody binding or dead cells. | Include an Fc receptor blocking step (e.g., with 2-10% goat serum). Use a viability dye (e.g., 7-AAD, DAPI) to exclude dead cells during analysis [35]. |

| Weak intracellular signal | Inadequate permeabilization. | Optimize the detergent and concentration. Use harsh detergents (e.g., 0.1-1% Triton X-100) for nuclear antigens and mild detergents (e.g., 0.2-0.5% saponin) for cytoplasmic antigens [35]. |

| Loss of cell surface signal | Fixation/permeabilization damages surface epitopes. | Always perform cell surface staining before the fixation and permeabilization steps for combined intra/extracellular analysis [35]. |

| Poor cell viability | Over-digestion during cell harvesting. | When creating a single-cell suspension from adherent cultures, avoid over-trypsinization. Gently dislodge cells and quench trypsin promptly [34]. |

Experimental Protocol: Combined Surface and Intracellular Antigen Staining

- Harvest and Wash: Harvest cells and create a single-cell suspension. Wash with a cold suspension buffer (e.g., PBS with 5-10% FBS). Determine cell count and viability (aim for 90-95%) [35].

- Viability Staining: Resuspend cells and incubate with an appropriate viability dye (e.g., 7-AAD) in the dark at 4°C. Wash twice [35].

- Surface Antigen Staining:

- Fixation and Permeabilization:

- Intracellular Staining: Incubate cells with antibodies against your target intracellular antigen. Wash thoroughly and resuspend in buffer for flow cytometric analysis [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials used in the featured techniques to guide your experimental setup.

| Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| TAT Peptide | A cell-penetrating peptide that facilitates direct, virus-like transport of nanoparticles into the cytosol, bypassing endosomal pathways [33]. |

| SH-PEG-5000 | Thiol-modified polyethylene glycol used to coat gold nanoparticles. Camouflages particles and reduces non-specific protein adsorption (bio-fouling) [33]. |

| Viability Dyes (e.g., 7-AAD) | DNA-binding dyes that only penetrate cells with compromised membranes. Used in flow cytometry to distinguish and exclude dead cells from analysis [35]. |

| FcR Blocking Reagent | (e.g., goat serum, human IgG). Prevents non-specific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors on immune cells, reducing background noise in flow cytometry [35]. |

| Permeabilization Detergents | Agents like Triton X-100 or saponin that disrupt the cell membrane to allow antibody access for intracellular staining in flow cytometry [35]. |

| CD Marker Antibodies | Fluorescently-labeled antibodies targeting Cluster of Differentiation (CD) surface antigens. Used to identify and characterize specific cell populations via flow cytometry [34]. |

FAQ: My research involves detecting pathogens. Are there localization-specific recognition pathways?

Yes, innate immune systems have specialized pathways for extracellular versus intracellular pathogen detection, a concept conserved in mammals and flies [36].

- Extracellular Recognition: Primarily mediated by receptors like Toll-like Receptors (TLRs). For example, TLR3 is involved in recognizing extracellular double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), a common viral pattern [37].

- Intracellular Recognition: Mediated by intracellular sensors like RIG-I and MDA5 (RNA helicases) and NOD proteins. These detect viral components within the cytosol and initiate powerful defense responses [36] [37].

- Key Insight: These pathways are not redundant; they utilize different signaling molecules. For instance, intracellular dsRNA signaling can lead to a more potent and sustained induction of antiviral genes (like IFNB) compared to extracellular signaling [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is there often a discrepancy between biochemical assay results and cellular assay results for the same compound? This discrepancy frequently arises because traditional in vitro biochemical assays are performed in simplified buffer systems (e.g., PBS) that do not replicate the complex intracellular environment. The cytoplasmic milieu has different physicochemical conditions, including molecular crowding, specific ionic composition, and viscosity, which can alter a ligand's binding affinity (Kd) and stability. To minimize this inconsistency, use buffers that more accurately mimic the cytoplasmic environment for biochemical measurements [10].

FAQ 2: What is "Redox Buffer Capacity" and why is it important to measure? Redox buffer capacity quantitatively describes a cell's ability to resist changes in its redox state upon exposure to oxidants or reductants. It is crucial because the intracellular redox state governs critical processes like proliferation, differentiation, and signal transduction. Measuring it helps predict whether reactive oxygen species (ROS) will activate beneficial redox signaling or cause deleterious oxidative stress, thus providing a quantitative basis for understanding redox biology [38] [39].

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally characterize a cell's redox buffer capacity? A standard protocol involves using a redox-sensitive fluorescent probe like 2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein (H2DCF). Cells are loaded with H2DCF and then challenged with specific oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻). The subsequent change in fluorescence intensity, which corresponds to the oxidation of the probe, is measured over time. The cell's redox buffer capacity is inversely related to the rate of fluorescence increase [38] [39].

FAQ 4: What are the common side effects of nutritional buffering supplements and how can they be managed?

- Sodium Bicarbonate (& Sodium Citrate): Often causes gastrointestinal (GI) distress. This can be mitigated by ingesting the dose with a carbohydrate-rich meal, using split-dose protocols, or using enteric-coated capsules [40].

- Beta-Alanine: Causes paresthesia (a transient tingling sensation on the skin). This side effect can be minimized by using sustained-release formulations or dividing the total daily dose into multiple smaller doses (e.g., 4-6 doses of 1-1.6 g) throughout the day [40].

FAQ 5: My cells are not responding to substrate stiffness cues in a 3D culture as expected. What could be wrong? Traditional 2D culture on flat, rigid surfaces (like glass or plastic) fails to replicate the complex mechano-chemical cues of the native extracellular matrix (ECM). Ensure your 3D culture system uses biomimetic scaffolds (e.g., specific hydrogels) that control parameters such as stiffness, nanotopography, and ligand presentation. The interplay between these physical cues and biochemical signaling is essential for proper cell function, including differentiation and proliferation [41] [42] [43].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Results in Redox Signaling Experiments

Problem: High variability in fluorescent signal when using redox probes like H2DCF.

| Possible Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|

| Probe Overloading | Optimize loading concentration and incubation time. Perform a dye titration curve to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio without causing cellular toxicity or auto-oxidation. |

| Oxidant Instability | Freshly prepare oxidant stocks (e.g., H2O2, ONOO⁻) immediately before use. Verify concentration spectrophotometrically if possible. Remember that cells have different redox buffer capacities for different oxidants [38]. |

| Inconsistent Cell State | Standardize cell culture conditions (passage number, confluence, serum starvation) and ensure consistent pre-treatment protocols, as the basal redox state is highly sensitive to the cell's metabolic condition. |

Issue 2: Lack of Ergogenic Effect from Buffering Supplementation

Problem: After administering beta-alanine or sodium bicarbonate, no performance improvement is observed in the model.

| Possible Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|

| Insufficient Loading/Dosing | For beta-alanine, ensure chronic supplementation (typically 3–6.4 g/day for at least 4 weeks) to significantly elevate muscle carnosine [40]. For sodium bicarbonate, use an acute dose of ~0.3 g/kg body mass, ingested 1–2 hours before testing [40]. |

| Incorrect Exercise Model | These supplements are most effective for exercises that rely heavily on glycolysis and last between 1-10 minutes, where acidosis is a major fatigue factor. Verify that your exercise protocol matches this intensity and duration [40]. |

| High Interindividual Variability | Account for factors like baseline muscle carnosine levels, diet, and training status. Use a placebo-controlled, crossover study design to account for individual responses. |

Issue 3: Poor Biomimicry in In Vitro Assays

Problem: Cellular behavior in synthetic environments does not reflect predicted or in vivo behavior.

| Possible Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|

| Over-simplified 2D Environment | Transition to 3D culture systems using hydrogels (e.g., fibrin, collagen, PEG-based) that allow control over mechanical (elasticity, viscoelasticity) and topographical cues [42] [43]. |

| Non-physiological Buffer System | Replace standard buffers like PBS with newly developed "cytomimetic" buffers that incorporate molecular crowding, physiological ionic strength, and glutathione to better mimic the cytoplasmic physicochemical environment [10]. |

| Ignoring Dynamic Remodeling | Implement co-cultures or use scaffolds that allow for cellular remodeling. The cell-ECM interaction is dynamic; cells synthesize and remodel their ECM, which in turn provides feedback to control cell function [41]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Assessing Redox Buffer Capacity Using H2DCF

Objective: To quantify the intracellular redox buffer capacity of adherent cells in response to hydrogen peroxide.

Materials:

- Cell culture (e.g., erythrocytes, cultured adherent cells)

- 2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA)

- Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) stock solution

- Appropriate cell culture buffer (e.g., HBSS, pH 7.4)

- Fluorescent plate reader or microscope

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in a 96-well black-walled plate and culture until desired confluence.

- Probe Loading: Wash cells with buffer. Load cells with 10-20 µM H2DCF-DA in buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash: Thoroughly wash cells 2-3 times with buffer to remove extracellular dye.

- Oxidant Challenge: Add a predetermined, sub-lethal concentration of H2O2 (e.g., 100-500 µM) to the wells. Include control wells with buffer only.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately place the plate in a fluorescent plate reader (Ex/Em ~485/535 nm) and take readings every 1-2 minutes for 60-90 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence intensity versus time. The redox buffer capacity is inversely proportional to the initial slope of the fluorescence increase. Compare slopes between treatment groups and controls.

Protocol 2: Chronic Beta-Alanine Supplementation Protocol

Objective: To elevate intramuscular carnosine content and increase intracellular buffering capacity.

Materials:

- Pharmaceutical-grade beta-alanine

- Placebo (e.g., maltodextrin)

Method:

- Dosing Regimen: Administer beta-alanine at a dose of 3–6.4 g per day.

- Dosing Strategy: To minimize paresthesia, split the total daily dose into 4-6 smaller doses of 1-1.6 g taken every 3-4 hours throughout the day, or use a sustained-release formulation.

- Duration: Continue supplementation for a minimum of 4 weeks; studies show muscle carnosine content increases progressively for at least 10-12 weeks.

- Verification: The ergogenic effect is typically assessed post-loading using high-intensity exercise tests (e.g., time to exhaustion at 110% VO₂max) [40].

Quantitative Data on Nutritional Buffering Supplements

Table 1: Summary of Nutritional Strategies to Modulate Buffering Capacity [40]

| Supplement | Primary Mechanism | Effective Dose & Duration | Key Exercise Benefits | Reported Effect Size / Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|