Bridging the Assay Gap: A Strategic Guide to Optimizing Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffers for Predictive Drug Discovery

This article addresses a critical challenge in biomedical research: the persistent discrepancy between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) results, which often delays drug development.

Bridging the Assay Gap: A Strategic Guide to Optimizing Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffers for Predictive Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article addresses a critical challenge in biomedical research: the persistent discrepancy between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) results, which often delays drug development. We explore the root cause—the stark difference between standard buffer conditions and the complex intracellular environment. Focusing on the strategic optimization of buffers to mimic key cytoplasmic physicochemical parameters—including molecular crowding, ionic composition, viscosity, and cosolvent content—this guide provides a foundational understanding, practical methodologies, troubleshooting advice, and robust validation frameworks. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, this resource aims to enhance the predictive power of in vitro assays, leading to more reliable data and accelerated translation of preclinical findings.

The Cytoplasmic Environment: Why Standard Buffers Fail and What We Must Mimic

A persistent challenge in drug discovery and chemical biology is the frequent inconsistency between activity data generated by biochemical assays (BcAs) and cell-based assays (CBAs) [1] [2]. This discrepancy can significantly delay research progress and lead to inefficient resource allocation [3]. This technical support guide addresses the root causes of this issue and provides actionable troubleshooting and methodologies to bridge the gap between simplified in vitro conditions and the complex intracellular environment.

FAQs: Understanding the Core Issue

Q1: Why do my IC50 values from biochemical assays often differ from those in cellular assays?

A: IC50 values from biochemical assays (BcAs) and cell-based assays (CBAs) frequently differ by orders of magnitude due to several factors [1] [2]:

- Physicochemical (PCh) Conditions: Standard BcAs use simplified buffer systems (like PBS) that do not replicate the crowded, viscous, and compositionally distinct interior of a cell [1] [2].

- Cellular Permeability: Compounds may not efficiently cross the cell membrane to reach the intracellular target [1] [2].

- Compound Stability: The compound might be metabolized or degraded within the cellular environment [1] [2].

- Off-Target Effects: The compound may interact with other unintended cellular components [3].

Q2: What is the most critical factor overlooked in standard biochemical assay buffers?

A: The most critical oversight is the failure to mimic the cytoplasmic environment [1] [2]. Common buffers like PBS mimic extracellular fluid, which has a high Na+/low K+ ratio. In contrast, the cytoplasm has a high K+/low Na+ ratio, high macromolecular crowding, different viscosity, and distinct lipophilicity [1] [2]. These differences can alter protein-ligand binding affinity (Kd) and enzyme kinetics by up to 20-fold or more [1].

Q3: Are all buffers suitable for simulating intracellular conditions?

A: No. Buffer selection is critical. Some buffers, like Tris, can permeate cells and disrupt their natural buffering capacity, while others may exert toxic or inhibitory effects on the biological system under study [4]. Inorganic buffers are often reactive and less suitable. Compatibility must be verified before use [4].

Q4: How can I tell if a discrepancy is due to assay conditions or a problem with my compound?

A: Troubleshoot systematically. The tables below guide you through common symptoms in both CBAs and BcAs, their possible causes, and solutions. If issues persist after addressing procedural errors (e.g., pipetting, incubation times), the discrepancy is likely due to fundamental differences between the assay environments, necessitating buffer reformulation [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Cellular Assay (CBA) Discrepancies

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Low compound permeability [1] [2]. | Use a cell-permeable analog or formulation aids (e.g., delivery reagents). |

| Compound instability or metabolism in cells [1] [2]. | Check for metabolites; use stable analogs or protease/intease inhibitors. | |

| Incorrect target engagement (off-target effects) [3]. | Conduct counter-screens and use chemical/genetic controls (e.g., CRISPR, RNAi). | |

| High Background Noise | Non-specific compound binding in complex cellular milieu [3]. | Optimize compound concentration; increase blocking agent concentration in assay buffer. |

| Cytotoxic effects at working concentration [3]. | Measure cell viability in parallel (e.g., with MTT or resazurin assays). | |

| Inconsistent Replicate Data | Variability in cell confluency, passage number, or health. | Standardize cell culture protocols and passage numbers; use low-passage cells. |

| Edge effects from uneven temperature or evaporation [5]. | Use plate sealers, avoid stacking plates, and ensure even incubation [5] [6]. |

Troubleshooting Biochemical Assay (BcA) Discrepancies and Optimization

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent with CBA Data | Buffer does not mimic cytoplasmic PCh conditions [1] [2]. | Reformulate buffer to mimic intracellular ion composition (high K+/low Na+), add crowding agents, and adjust viscosity. |

| Assay temperature or pH does not reflect physiological conditions [1]. | Ensure assay is run at 37°C and physiological pH (e.g., 7.2-7.4). | |

| Poor Standard Curve | Incorrect dilution calculations or pipetting error [5] [6]. | Double-check calculations and verify pipette calibration and technique. |

| Capture antibody not properly binding to plate [5] [6]. | Ensure an ELISA-approved plate is used; optimize coating conditions and duration. | |

| High Uniform Background | Insufficient washing [5] [6]. | Increase wash number and duration; include a soak step. |

| Antibody concentration too high [6]. | Titrate primary and secondary antibodies to optimal concentration. | |

| Inconsistent Results Between Experiments | Reagents not at room temperature at start of assay [5]. | Allow all reagents to equilibrate at room temperature for 15-20 minutes before starting. |

| Variation in incubation times or temperature [5] [6]. | Strictly adhere to protocol-specified incubation times and use a calibrated incubator. |

Experimental Protocol: Mimicking Cytoplasmic Conditions

This protocol provides a methodology for creating a Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer (CMB) to make biochemical assay conditions more physiologically relevant [1].

Objective: To reformulate standard biochemical assay buffers to more closely reflect the intracellular environment, thereby reducing discrepancies with cellular assay data.

Workflow Overview:

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

| Research Reagent | Function in Assay |

|---|---|

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Provides high K+ concentration (~140-150 mM) to mimic the primary intracellular cation composition [1] [2]. |

| HEPES or PIPES Buffer | Organic, zwitterionic buffers suitable for physiological pH ranges (e.g., 7.0-7.4) with low cellular permeability and toxicity [4]. |

| Macromolecular Crowding Agents(e.g., Ficoll-70, PEG, Dextran) | Mimic the high concentration of macromolecules (~20-30% w/v) in the cytoplasm, which affects ligand binding and enzyme kinetics via excluded volume effects [1] [2]. |

| Glycerol or Sucrose | Modifies solution viscosity to better approximate the viscous cytoplasmic environment, influencing diffusion and binding rates [1] [2]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | A reducing agent that can mimic the reducing environment of the cytosol. Use with caution as it may disrupt proteins reliant on disulfide bonds [1]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Prepare Base Buffer:

- Create a base buffer with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4.

- Add KCl to a final concentration of 140-150 mM.

- Add MgCl₂ to 1-2 mM (critical for many ATP-dependent enzymes).

- Adjust the pH to 7.4 at 37°C.

Introduce Macromolecular Crowding:

- Add a chemically inert crowding agent like Ficoll-70 (PMC: 70,000) to a final concentration of 50-100 g/L [1].

- Gently stir to dissolve completely without foaming.

Adjust Viscosity (Optional):

- To further modulate viscosity, add 5-10% (v/v) glycerol.

- Note that viscosity and crowding are related but distinct physical parameters.

Validate the CMB:

- Run your biochemical assay in parallel using the new CMB and your standard buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Compare the output parameters (Kd, IC50, enzyme kinetics). A successful CMB should yield activity data that more closely aligns with your cellular assay results [1].

Key Concepts and Signaling Pathways

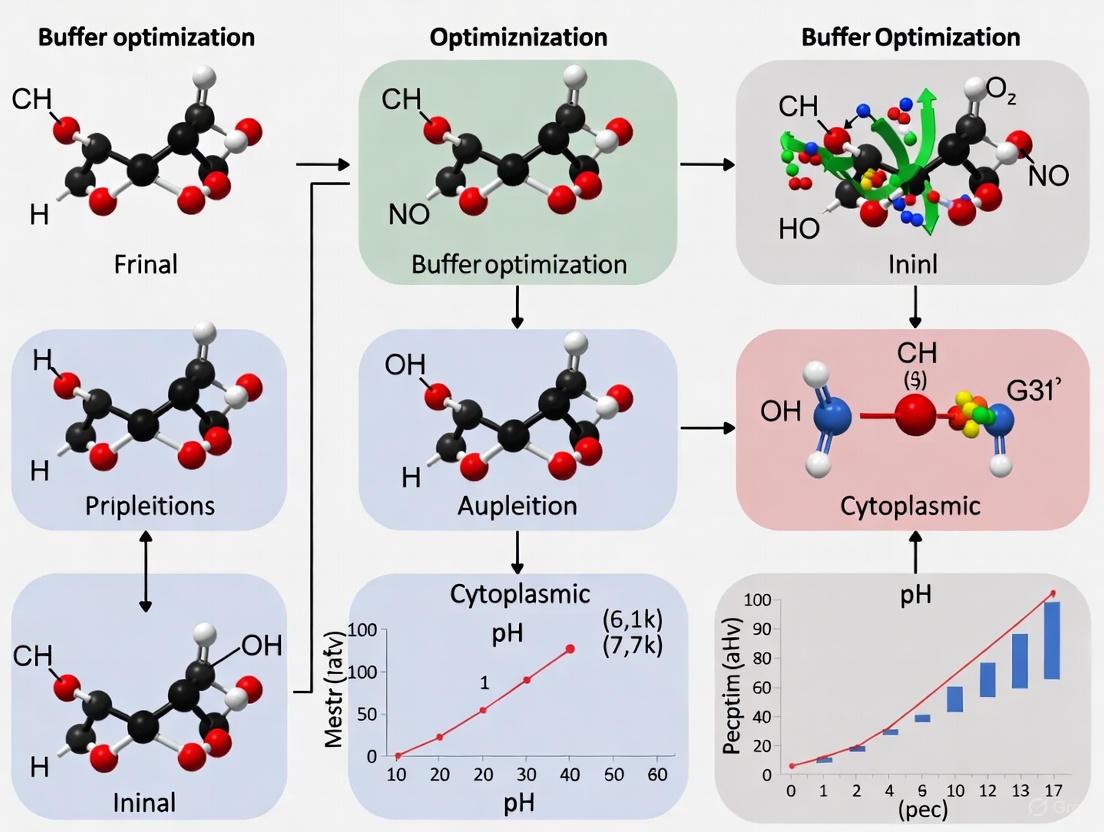

The following diagram summarizes the core concepts behind the assay discrepancy and the strategic solution of using a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: Why is there often a discrepancy between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) results? A persistent issue in research is the inconsistency between activity values (like Kd or IC50) obtained from purified biochemical assays and those from cellular assays. While factors like compound permeability and stability are often blamed, the discrepancy frequently arises because standard biochemical assays use simplified buffers like PBS that do not replicate the complex intracellular environment. This can lead to Kd values differing by up to 20-fold or more from measurements made inside cells [2] [7].

FAQ: My protein-ligand binding results are inconsistent. Could my buffer be the problem? Yes. The binding affinity (Kd) between a ligand and its target is highly sensitive to the physicochemical conditions. Standard buffers like PBS have an ionic composition dominated by sodium (157 mM Na⁺, 4.5 mM K⁺), which is the inverse of the cytoplasmic environment (approx. 14 mM Na⁺, 140-150 mM K⁺). Furthermore, PBS lacks critical cytoplasmic features like macromolecular crowding, correct viscosity, and specific cosolvents, all of which can significantly alter binding equilibria and kinetics [2].

FAQ: How can I simply adjust my current assay to better mimic cytoplasmic conditions? A straightforward initial step is to modify the ionic composition of your buffer. Research on kinesin-microtubule gliding assays has shown that reducing ionic strength can profoundly affect protein interactions. Switching from a standard BRB80 buffer (ionic strength ~184 mM) to a low ionic strength BRB10 buffer (ionic strength ~28.85 mM) enhanced kinesin-microtubule binding affinity, leading to longer interaction times and slower, more processive movement. This simple change significantly improved the sensitivity of the detection assay [8].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Biochemical and Cellular Assays

Potential Cause: The use of oversimplified buffer systems (e.g., PBS) that mimic extracellular conditions, leading to inaccurate measurements of binding affinity and enzyme kinetics in an intracellular context [2].

Solution: Develop a biochemical assay buffer that more closely mimics the cytoplasmic environment. The table below summarizes the key parameters to adjust.

Table: Key Physicochemical Differences Between PBS and Cytoplasm

| Parameter | Standard PBS Buffer | Cytoplasmic Environment | Impact on Molecular Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Composition | High Na⁺ (157 mM), Low K⁺ (4.5 mM) [2] | High K⁺ (~150 mM), Low Na⁺ (~14 mM) [2] | Alters electrostatic protein interactions and stability [2]. |

| Macromolecular Crowding | Absent or very low [2] | High (20-40% of volume occupied by macromolecules) [2] [9] | Increases effective protein concentrations, can enhance binding affinities and alter reaction rates by up to 2000% [2]. |

| Viscosity | Similar to water [2] | Higher than water due to crowding [2] | Slows diffusion, affects conformational dynamics and association/dissociation rates [2]. |

| pH | Typically 7.4 [2] | ~7.2, tightly regulated [2] | Influences protonation states of ionizable groups on proteins and ligands [2]. |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing [2] | Reducing (high glutathione) [2] | Affects disulfide bond formation and stability of cysteine residues [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Buffer Ionic Strength

- Objective: To enhance the sensitivity of a motor-protein-based detection assay by reducing buffer ionic strength to strengthen protein-filament interactions [8].

- Materials:

- Standard Buffer: BRB80 (80 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8 with KOH; total ionic strength ~184 mM) [8].

- Low Ionic Strength Buffer: BRB10 (10 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.8 with KOH; total ionic strength ~28.85 mM) [8].

- Purified kinesin and tubulin proteins.

- Flow chambers, TIRF microscope, ATP, antifade agents.

- Method:

- Immobilize kinesin motors on a glass surface within a flow chamber.

- Introduce fluorescently labeled microtubules and an ATP-containing motility solution in either BRB80 or BRB10 buffer.

- Image microtubule gliding using time-lapse microscopy.

- Track microtubule movement to calculate gliding speeds.

- For single-molecule analysis, immobilize microtubules and track the movement of individual GFP-kinesin molecules in both buffers to determine velocity, run length, and interaction time [8].

- Expected Outcome: In the low ionic strength buffer (BRB10), you will observe slower microtubule gliding speeds, reduced single-motor stepping velocity, and a significant increase in motor run length and interaction time with the microtubule, indicating enhanced affinity [8].

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer.

Problem: Buffer-Induced Changes in Protein Behavior

Potential Cause: Nonspecific or specific interactions between buffering agent molecules and the protein of interest, which can induce changes in conformational equilibria, dynamics, and catalytic properties [10].

Solution: Use a universal buffer mixture. When designing experiments where pH is a variable, avoid switching between different buffering agents, as this can make it impossible to decouple buffer-induced effects from pH-induced effects.

Experimental Protocol: Employing a Universal Buffer

- Objective: To study protein behavior across a pH range without introducing artifacts from changing buffer compositions [10].

- Materials:

- Universal buffer components (e.g., HEPES, MES, Bis-Tris, Sodium Acetate).

- Standard acids (e.g., HCl) and bases (e.g., NaOH) for titration.

- Method:

- Prepare a universal buffer by mixing several buffering agents with overlapping pKa values (e.g., HEPES, MES, and sodium acetate).

- Titrate the universal buffer mixture across the desired pH range. The combined buffer will show a linear response to added acid or base, providing consistent buffering capacity.

- Use this single universal buffer for all experiments, varying only the pH. This ensures the small-molecule composition of the solution remains constant [10].

- Expected Outcome: The observed changes in protein structure or function can be confidently attributed to the change in pH, rather than to differential interactions with multiple buffer molecules [10].

Diagram 2: Mechanism of how buffer conditions influence experimental results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table: Essential Reagents for Cytoplasmic Environment Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Key Feature / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Agents (e.g., Ficoll, PEG, Dextran) | Mimics macromolecular crowding of cytoplasm (20-40% cell volume) [2]. | Increases effective protein concentrations; can be used to study crowding effects on binding and folding. |

| HEPES, PIPES, MES Buffers | Common components for universal buffer systems [10]. | Allows for pH variation studies without changing buffer composition, isolating pH effects. |

| K⁺-based Salts | Adjusts ionic strength and cation balance to match cytoplasm [2] [8]. | Replaces Na⁺-based salts (e.g., in PBS) to create a more physiologically relevant ionic environment. |

| Tubulin Tracker Dyes (e.g., CellLight Tubulin-GFP) | Labels microtubules in live cells [11]. | Enables visualization of cytoskeletal dynamics and organization under different conditions. |

| Phalloidin Conjugates (e.g., Alexa Fluor Phalloidin) | Stains F-actin in fixed and permeabilized cells [11]. | Useful for examining cell shape and cytoskeletal structure as a readout of cellular state. |

| DTT / β-mercaptoethanol | Mimics the reducing environment of the cytoplasm [2]. | Use with caution: Can disrupt native disulfide bonds; suitability depends on specific protein system. |

FAQs: Bridging the Gap Between Biochemical and Cellular Assay Data

FAQ 1: Why do my measured Kd values from biochemical assays often disagree with the activity observed in cellular assays?

This is a common challenge in research and drug development. The discrepancy often arises because standard biochemical assays are performed in simplified buffer solutions (like PBS) that do not replicate the complex intracellular environment [7] [2]. Key factors responsible include:

- Macromolecular Crowding: The cell cytoplasm is packed with macromolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, etc.), occupying 30–40% of the volume. This crowding can significantly alter binding affinities and reaction rates through the excluded volume effect, which is absent in standard dilute buffers [2] [12].

- Ionic Composition: Common buffers like PBS have a high Na+/K+ ratio, mimicking extracellular fluid. In contrast, the cytoplasm has a high K+/Na+ ratio (~140-150 mM K+ vs. ~14 mM Na+). This difference in ionic composition can affect protein structure and electrostatic interactions, thereby influencing Kd [2].

- Viscosity and Cosolvents: The cytoplasmic environment has higher viscosity and contains various small molecules (kosmotropes, metabolites) that can influence protein stability, folding, and ligand binding through non-steric (sticking) interactions [2] [12].

FAQ 2: What are the key physicochemical parameters of the cytoplasmic environment that I should replicate in my in vitro assays?

To better mimic the intracellular milieu, your buffer should be designed to account for the following parameters [2]:

- Macromolecular Crowding: Introduce inert, soluble macromolecules like Ficoll or polyethylene glycol (PEG) to simulate the excluded volume effect.

- Ionic Strength and Composition: Use a salt composition that reflects the high K+/low Na+ environment of the cytoplasm.

- Cosolvents and Kosmotropes: Include compounds like glycerol, which can mimic the influence of small cytosolic metabolites on protein solvation.

- pH: Maintain a physiological pH of ~7.4.

- Viscosity: Adjust the solution viscosity to be closer to that of the cytoplasm.

FAQ 3: Can you provide a specific buffer recipe that mimics cytoplasmic conditions?

Yes, based on recent research, an effective cytoplasmic mimic can be created by combining agents that account for both steric crowding and non-steric interactions. One validated formulation is a mixture of 150 mg/mL Ficoll PM 70 and 60% Pierce IP Lysis Buffer [12].

- Ficoll acts as an inert macromolecular crowder.

- The Lysis Buffer provides ions (150 mM NaCl), a kosmotrope (5% glycerol), and a buffer (25 mM Tris). This combination has been shown to reproduce the in-cell stability and folding kinetics for proteins that are differently impacted by the cellular environment [12].

Quantitative Data: The Effect of Cytoplasmic Conditions on Kd

The following table summarizes documented shifts in Kd values when moving from standard buffer conditions to environments that more closely mimic the cytoplasm.

Table 1: Impact of Cytomimetic Conditions on Dissociation Constants (Kd)

| System / Condition | Kd in Standard Buffer | Kd in Cytomimetic Buffer / In-Cell | Observed Fold-Change | Key Factor Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Protein-Ligand Interactions | Varies | Varies | Up to 20-fold or more [2] | Macromolecular Crowding |

| Phosphoglycerate Kinase (PGK) Stability (Tm) | ~39°C [12] | ~44°C (in-cell) [12] | Stabilized (ΔTm +5°C) | Combined crowding & non-steric interactions [12] |

| Variable major protein-like sequence expressed (VlsE) Stability (Tm) | ~40°C [12] | ~35°C (in-cell) [12] | Destabilized (ΔTm -5°C) | Combined crowding & non-steric interactions [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Kd Under Cytomimetic Conditions

This protocol outlines the steps to determine the Kd of a protein-DNA interaction using an Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) in a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer.

A. Buffer Preparation

- Prepare your standard binding buffer (e.g., Tris or PBS-based).

- Prepare the cytomimetic buffer supplement: 150 mg/mL Ficoll PM 70 in 60% Pierce IP Lysis Buffer [12]. Ensure it is fully dissolved and filter-sterilized if necessary.

- Mix your standard binding buffer with the cytomimetic supplement to the desired final concentration for your assay (e.g., 1X standard buffer with a final concentration of 150 mg/mL Ficoll and 60% Lysis Buffer).

B. Binding Reaction

- Titration Series: Prepare a series of tubes with a constant, low concentration of your DNA substrate (fluorescently labeled for detection) that is below the expected Kd. The concentration should be sufficient for detection [13].

- Titrate increasing concentrations of your purified protein across the tubes.

- Incubate the reactions in your standard and cytomimetic buffers in parallel to allow the binding to reach equilibrium.

C. Gel Electrophoresis and Analysis

- Native PAGE: Load the binding reactions onto a native polyacrylamide gel. The protein-DNA complex will migrate more slowly than the free DNA [13].

- Visualization and Quantification: Visualize the DNA using a fluorescence scanner or imager. Use software like ImageJ to quantify the band intensities for the free DNA and the protein-DNA complex in each lane [13].

- Data Fitting: For each protein concentration, calculate the fraction of DNA bound: Fraction Bound = [ES] / ([S] + [ES]).

- Plot the fraction bound against the total protein concentration. Fit the data to the following equation to determine the Kd value: Fraction Bound = [E]total / (Kd + [E]total) [13].

- Compare the Kd values obtained in the standard buffer versus the cytomimetic buffer.

Experimental Workflow for Kd Determination in Cytomimetic Buffer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytomimetic Buffer Preparation

| Reagent | Function in Cytomimetic Buffers | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll PM 70 | Inert, highly-branched polymer used to simulate macromolecular crowding via the excluded volume effect [12]. | Larger crowders generally have a greater stabilizing effect on proteins than smaller ones [12]. |

| Pierce IP Lysis Buffer | Provides ions, Tris buffer, and kosmotropes (glycerol) to mimic cytoplasmic non-steric (sticking) interactions [12]. | A commercially available, consistent source for these components. |

| HEPES | Common biological buffer with a pKa of ~7.5, suitable for physiological pH studies [14] [10]. | Can chelate metal ions; part of some universal buffer mixtures [10]. |

| Histidine | Common buffer for biologic formulations, effective in the pH 5.5-6.5 range; pKa ~6.01 [14] [15]. | Often used in platform formulations for monoclonal antibodies [15]. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Used to adjust the ionic composition to reflect the high K+ intracellular environment [2]. | Critical for replicating the correct cationic balance versus Na+-based PBS. |

| Glycerol | Acts as a kosmotrope, influencing protein solvation and stability, and helps modulate solution viscosity [12]. | A common component in lysis and storage buffers. |

Root Causes of Data Discrepancy Between Standard and Cytoplasmic Conditions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) inadequate for mimicking the cytoplasmic environment in biochemical assays?

PBS is formulated to mimic extracellular fluid, not the intracellular cytoplasm. Its ionic composition is the inverse of what is found inside cells. The dominant cation in PBS is sodium (Na+ at ~157 mM), with very low potassium (K+ at ~4.5 mM). In contrast, the cytoplasm is characterized by a high potassium concentration (~140-150 mM) and low sodium (~14 mM) [2]. Furthermore, PBS lacks critical cytoplasmic components such as macromolecular crowding agents, which significantly influence protein interactions, diffusion, and stability [2].

Q2: How does molecular crowding affect the binding of a transcription factor to its promoter DNA?

Molecular crowding impacts both the diffusion and the binding kinetics of macromolecules. Crowding agents generally reduce the diffusion rate of large molecules like transcription factors due to volume exclusion effects. However, crowding can also enhance binding by increasing the association rate constant and decreasing the dissociation rate constant. The size of the crowding molecule matters; larger crowding agents (e.g., 2x10⁶ g/mol dextran) can enhance binding more significantly than smaller ones (e.g., 6x10³ g/mol dextran) [16]. This can lead to increased gene expression rates under crowded conditions, especially for genetic modules with weaker promoters or ribosomal binding sites that have inherently higher dissociation constants [16].

Q3: My drug candidate shows excellent affinity in a biochemical assay but poor activity in cellular assays. Could cytoplasmic mimicry explain this discrepancy?

Yes, this is a common issue often rooted in the differences between simplified in vitro conditions and the complex intracellular milieu. The discrepancy can be attributed to several factors related to cytoplasmic mimicry [2]:

- Molecular Crowding and Viscosity: The crowded cellular environment can alter the dissociation constant (Kd) of protein-ligand interactions, with in-cell Kd values differing from purified assay values by up to 20-fold or more.

- Ionic Composition and Strength: The specific ionic environment, particularly the high K+/low Na+ balance, can affect electrostatic protein-ligand interactions that are sensitive to ionic strength.

- Lipophilicity and Solvation: The cytosolic environment can influence the hydrophobic solvation of compounds.

- Membrane Permeability: The compound may not efficiently cross the cell membrane to reach its intracellular target.

Implementing biochemical assays under conditions that mimic the cytoplasm (e.g., using appropriate salts, crowding agents, and cosolvents) can help bridge this activity gap [2].

Q4: What is a common error in buffer preparation that can lead to inconsistent ionic strength?

A frequent error is the "pH overshoot and correction" method. For example, if you are preparing a phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 and accidentally add too much phosphoric acid, lowering the pH to 6.0, then adding sodium hydroxide to bring it back to 7.0, you will have inadvertently increased the buffer's total ionic strength. A buffer prepared this way will generate a higher current in techniques like capillary electrophoresis and yield less precise migration times compared to a buffer prepared correctly on the first attempt [17]. Always try to adjust pH carefully to the target value without over-shooting.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Biochemical and Cellular Assays

Potential Cause 1: The ionic strength and cation composition of your assay buffer do not reflect the cytoplasmic environment.

Solution:

- Replace extracellular-like buffers (e.g., PBS) with buffers that have a high K+/low Na+ composition.

- Calculate and adjust the ionic strength accurately. For simple salts like KCl, ionic strength equals the concentration. For buffers, the calculation is more complex as it depends on pH. Use the formula: I = ½ Σ (C_i * Z_i²) where C_i is the molar concentration of ion i and Z_i is its charge [18].

- Refer to Table 1 for target cytoplasmic ion concentrations.

Potential Cause 2: Lack of macromolecular crowding in the biochemical assay.

Solution:

- Introduce inert, water-soluble crowding agents into your assay buffer.

- Select the crowding agent based on size: Larger agents (e.g., Ficoll 400, Dex-Big) may enhance binding interactions more than smaller ones (e.g., Dex-Small), which can sometimes cause a biphasic (increase then decrease) response in reaction rates at high densities [16].

- Refer to Table 2 for common crowding agents and their properties.

Problem: Unstable Membrane Protein Activity After Purification

Potential Cause: Detergents used for solubilization are stripping away essential lipids or disrupting native protein conformations.

Solution: Use a membrane mimetic system to stabilize the protein in a native, lipid-based environment.

- Select a membrane mimetic: Common systems include Nanodiscs, Saposin Lipid Nanoparticles (SapNPs), Peptidiscs, and SMA Lipid Particles (SMALPs) [19].

- Follow a reconstitution protocol: The general workflow involves incubating the detergent-solubilized protein with lipids and a scaffold protein (e.g., Membrane Scaffold Protein for Nanodiscs, Saposin A for SapNPs), followed by detergent removal to form a soluble, nanoscale disc encircling the protein [19].

- Application: These mimetics are compatible with structural studies (e.g., Cryo-EM) and functional assays like ligand binding, as demonstrated in Membrane-mimetic Thermal Proteome Profiling (MM-TPP) [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating the Ionic Strength of a PIPES Buffer

This protocol explains how to calculate the ionic strength of a divalent buffer like PIPES, where the charge of the buffer species changes with pH [18].

Materials:

- PIPES acid form or potassium salt

- KOH or HCl for pH adjustment

- pH meter

Method:

- Determine the total concentration of PIPES, [PIPES]total.

- Measure the pH of the buffer solution.

- Calculate the fraction of PIPES in the monovalent (acid) form and the divalent (base) form using the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation:

- Fraction in acid form (Frac_Monovalent) = 1 / (1 + 10^(pH - pKa))

- Fraction in base form (FracDivalent) = 1 - FracMonovalent

- The pKa of PIPES is 6.76 at 25°C.

- The concentration of K+ ions is equal to [PIPES]total * (1 + Frac_Divalent). This accounts for one K+ to neutralize the first proton and an additional K+ for every molecule in the divalent form.

- Calculate the ionic strength (I) using the formula: I = 0.5 * ( [Monovalent PIPES](1)² + [Divalent PIPES](2)² + [K+](1)² )* I = 0.5 * [PIPES]total * ( Frac_Monovalent + 4FracDivalent + 1 + FracDivalent )* I = 0.5 * [PIPES]total * ( 1/(1+10^(pH-pKa)) + 4(1 - 1/(1+10^(pH-pKa))) + (1 + (1 - 1/(1+10^(pH-pKa)))) )* [18]

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Molecular Crowding on Gene Expression

This cell-free expression protocol quantifies how crowding agent size and density affect transcription rates [16].

Materials:

- Cell-free protein expression system (e.g., S12 bacterial extract and supplement)

- Plasmid DNA with a T7 promoter driving a reporter gene (e.g., cyan fluorescent protein, CFP)

- Crowding agents: Dextran (2x10⁶ g/mol and 6x10³ g/mol), Ficoll 400, PEG

- Fluorescence plate reader

Method:

- Prepare a series of cell-free expression reactions containing your genetic template.

- Supplement each reaction with a different crowding agent across a range of concentrations (e.g., 0% to 10% w/v).

- Incubate the reactions at a constant temperature (e.g., 37°C).

- Monitor the production of the fluorescent reporter protein (CFP) over time using a plate reader.

- Expected Results:

- With large crowding agents (Dex-Big, Ficoll 400), you should observe a monotonic increase in gene expression rate with increasing crowding density.

- With small crowding agents (Dex-Small, PEG8000), you may observe a biphasic response: expression rates increase initially but then decrease after a specific crowding density due to severely hindered diffusion [16].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Target Parameters for a Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer

Table summarizing key physicochemical parameters of the cytoplasm to guide buffer design. [2]

| Parameter | Cytoplasmic Condition | Common Inadequate Substitute (e.g., PBS) |

|---|---|---|

| Cation Composition | High K+ (~140-150 mM), Low Na+ (~14 mM) | High Na+ (~157 mM), Low K+ (~4.5 mM) |

| pH | ~7.2 (tightly regulated) | ~7.4 (extracellular) |

| Macromolecular Crowding | 20-40% of volume occupied (~400 mg/mL) [21] | None (dilute solution) |

| Ionic Strength | Variable (~150-200 mM) | ~170 mM (but wrong ion ratio) |

| Redox Potential | Reducing (high glutathione) | Oxidizing |

Table 2: Common Reagents for Cytoplasmic Mimicry

A selection of reagents used to simulate cytoplasmic conditions in vitro.

| Reagent Category | Example Compounds | Function in Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Agents | Ficoll, Dextran, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [16] [21] | Mimic volume exclusion effects, modulate diffusion and binding kinetics. |

| Ionic Strength Modulators | KCl, Potassium Glutamate | Adjust total ionic strength to physiological levels using the correct K+/Na+ balance. |

| Biological Buffers | HEPES, PIPES, MOPS | Maintain physiological pH with minimal side effects and appropriate pKa. |

| Membrane Mimetics | Nanodiscs, Saposin NPs (Salipro), Peptidiscs [19] [20] | Stabilize membrane proteins in a native lipid environment without denaturing detergents. |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol [2] | Mimic the reducing environment of the cytoplasm (use with caution as they may disrupt disulfide bonds). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | The primary salt for adjusting ionic strength and replicating the high intracellular K+ concentration. |

| HEPES Buffer (pKa 7.48) | A zwitterionic organic buffer effective at physiological pH, with lower conductivity and fewer metal-chelating properties than phosphate buffers. |

| Ficoll 400 (400,000 g/mol) | A large, inert polysaccharide crowding agent. Useful for studying enhanced molecular binding and for creating density gradients. |

| Dextran (6,000 g/mol) | A smaller crowding agent used to study the size-dependent effects of crowding, such as biphasic impacts on reaction rates. |

| Peptidisc Scaffold | A synthetic peptide that self-assembles with membrane proteins and lipids to form a water-soluble "disc," preserving the native membrane protein complex for downstream assays [20]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | A reducing agent to maintain a reducing environment similar to the cytosol. Critical for proteins with cysteine residues but can denature proteins reliant on disulfide bonds [2]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram: MM-TPP Workflow

Diagram: Cytoplasmic Parameters

From Theory to Bench: Formulating and Preparing a Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer

Troubleshooting Common Issues with Crowding Agents

Question: Why is there a discrepancy between the binding affinity (Kd) I measure in my simple buffer and reported cellular activity?

This is a frequently encountered issue. The discrepancy often arises because standard biochemical assays are performed in simplified buffers like PBS, which do not replicate the complex intracellular environment. The cytoplasm is highly crowded, viscous, and has a specific ionic composition, all of which can significantly alter molecular interactions [2]. To bridge this gap, you should use a crowding buffer that mimics the cytoplasmic environment. Measurements taken under such conditions can show Kd values that differ from those in dilute buffers by up to 20-fold or more, providing a more accurate prediction of cellular activity [2].

Question: My protein is aggregating unexpectedly after adding a crowding agent. What could be the cause?

Unexpected aggregation can occur due to the excluded volume effect, a fundamental principle of macromolecular crowding. Crowding agents reduce the available space, which can stabilize proteins but also increase the local concentration of your macromolecule, potentially promoting aggregation [22]. To troubleshoot:

- Check crowder-protein interactions: Ensure the crowder is inert. Some crowders might have weak, non-specific interactions with your protein. Switching from a polymer like Ficoll to an inert protein like BSA might help.

- Optimize concentration: Start with a lower volume fraction of crowder (e.g., 5-10%) and gradually increase it while monitoring for aggregation.

- Verify sample purity: Contaminants in your protein sample can be exacerbated by crowding conditions.

Question: How do I choose between a polymer crowder (like PEG or Ficoll) and a protein crowder (like BSA)?

The choice depends on your research question and the properties you wish to mimic. The table below compares the key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Polymer and Protein Crowding Agents

| Feature | Polymer Crowders (e.g., PEG, Ficoll, Dextran) | Protein Crowders (e.g., BSA, Ovalbumin) |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Chemically defined, low cost, low UV absorbance, minimal enzymatic activity. | More biologically relevant, can mimic weak interactions present in cells. |

| Disadvantages | Can be hypersensitive to solution conditions (e.g., pH, salt), may engage in specific chemical interactions. | Potential for specific biological activity, higher cost, can interfere with assays (e.g., UV absorbance). |

| Best For | Studying the fundamental, hard-core excluded volume effect in a controlled system. | Creating a more physiologically realistic environment that includes both excluded volume and weak interactions. |

Generally, polymer crowders are excellent for investigating the pure effect of excluded volume. In contrast, protein crowders provide a more complex and native-like environment, as the cytoplasm contains a high concentration of various proteins [22].

Question: Can macromolecular crowding really alter the structure of the peptide assemblies I am studying?

Yes, significantly. Computational and experimental studies have shown that crowder size and hydrophobicity can dictate the supramolecular architecture of peptide assemblies [23]. For instance:

- Small hard-sphere crowders can promote the formation of thick, multilayer fibrils.

- Large, highly hydrophobic crowders can favor the stabilization of monolayer β-sheet structures and suppress fibril formation [23]. If your assembly is not forming as expected, consider screening crowders of different sizes and surface properties to guide the morphology.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Molecular Crowding

Q: What is the fundamental difference between the intracellular environment and standard assay buffers like PBS? A: The intracellular cytoplasm is a densely packed environment with a high concentration of macromolecules (80-200 g/L), leading to macromolecular crowding. This results in limited free water, high viscosity, and a distinct ionic composition (high K+, low Na+). In contrast, PBS has a low macromolecular content and an ionic composition (high Na+, low K+) that mimics extracellular fluid, not the cytoplasm [2].

Q: Why is the ionic composition of my crowding buffer important? A: The ionic composition directly affects protein stability and function. The cytoplasm is rich in potassium (K+ ~140-150 mM) and low in sodium (Na+ ~14 mM), which is the reverse of PBS (Na+ ~157 mM, K+ ~4.5 mM) [2]. Using a buffer with a cytoplasmic-like ionic balance is crucial for obtaining biologically relevant data.

Q: How does macromolecular crowding affect enzyme kinetics? A: Crowding can significantly alter enzyme kinetics by affecting protein folding, substrate diffusion, and conformational dynamics. Experimental data has shown that enzyme kinetics can change by as much as 2000% under crowding conditions [2].

Q: Should I include reducing agents in my cytoplasm-mimicking buffer? A: The cytosol is a reducing environment. While this is an important parameter, the inclusion of reducing agents like DTT must be considered carefully. They can break disulfide bonds and denature proteins that rely on them for structural integrity. Therefore, their use should be tailored to your specific protein system and is not universally recommended for all cytoplasmic mimicry buffers [2].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Measuring Ligand Binding Affinity (Kd) Under Crowding Conditions

This protocol outlines the steps to determine a dissociation constant (Kd) under conditions that mimic the cytoplasmic environment, helping to bridge the gap between biochemical and cellular assay data [2].

1. Preparation of Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer:

- Crowding Agent: Select and add your chosen crowder. A common starting point is 100-150 g/L of a polymer like Ficoll 70 or a protein like BSA to achieve a volume fraction of 0.1-0.2.

- Ionic Composition: Use a buffer with 140-150 mM KCl, 10-14 mM NaCl, 1-2 mM MgCl₂, and 1 mM EGTA.

- Buffering System: Use 10-20 mM HEPES (pH 7.2-7.4).

- Reducing Agent (Optional): Add 1-2 mM DTT or an equivalent if your system requires a reducing environment and the protein is not destabilized.

- Osmolarity: Adjust to ~300 mOsm and verify with an osmometer.

2. Performing the Binding Assay:

- Control: Run your standard binding assay (e.g., Isothermal Titration Calorimetry - ITC, Surface Plasmon Resonance - SPR, or fluorescence anisotropy) in your standard buffer (e.g., PBS) and in the cytoplasm-mimicking buffer.

- Data Collection: Ensure all other conditions (temperature, pH, protein concentration) are identical between the two buffers.

- Analysis: Fit the binding data from both conditions to your standard model to extract the Kd. Compare the values to see the crowding effect.

The workflow below illustrates the key decision points in this protocol.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Kd measurement in crowding conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Crowding Experiments

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytoplasmic Mimicry Experiments

| Reagent Category | Example | Function in the Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Polymers | Ficoll 70, PEG (various MW), Dextran | Inert polymers that create volume exclusion. Different sizes (e.g., 10-80 Å diameter) can be screened to modulate peptide assembly structure [23]. |

| Protein Crowders | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Ovalbumin | Provide a more biologically relevant crowding environment, potentially including weak, non-specific interactions. |

| Salts for Ionic Balance | KCl, NaCl, MgCl₂, EGTA | To replicate the high K+ (140-150 mM) and low Na+ (~14 mM) environment of the cytoplasm, which is crucial for accurate biomolecular function [2]. |

| Buffering Agents | HEPES | Maintains physiological pH (~7.2-7.4) in a cytoplasmic-mimicking buffer. |

| Reducing Agents (Use with Caution) | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol | Mimics the reducing nature of the cytosol. Note: Can denature proteins with structural disulfide bonds [2]. |

| Detergent | Digitonin | Used in cell permeabilization protocols to create "ghost cells" for studying internalization in a controlled, yet crowded, environment [24]. |

Advanced Topics: Computational Approaches

Computational methods are invaluable for understanding molecular crowding at the atomic level, helping to interpret and predict experimental results. Key techniques include [25]:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Model the detailed motions of atoms and molecules over time in a crowded environment.

- Coarse-Grained Modeling: Sacrifices atomic detail for computational efficiency, allowing the study of larger systems and longer timescales.

- Monte Carlo Simulations: Uses random sampling to understand equilibrium properties of crowded systems.

- Brownian Dynamics: Simulates the diffusion and collision of molecules in a crowded milieu.

- Multi-scale Modeling: Combines different levels of resolution (e.g., quantum mechanics with molecular mechanics) to provide a comprehensive view.

Future directions in the field involve the integration of machine learning with these classical simulation methods to accelerate discovery and improve predictive power [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between intracellular and extracellular ionic composition?

The primary difference lies in the concentration of potassium (K⁺) and sodium (Na⁺) ions. The intracellular fluid (cytoplasm) is characterized by a high concentration of K⁺ and a low concentration of Na⁺. Conversely, the extracellular fluid has a high concentration of Na⁺ and a low concentration of K⁺ [26]. Maintaining this gradient is crucial for a wide range of cellular processes, including membrane potential and cell signaling [27].

Why is it important to mimic the cytoplasmic K⁺/Na⁺ ratio in biochemical assays?

Many drug targets and metabolizing enzymes are located inside the cell. Using standard buffers like Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), which has a high Na⁺ (157 mM) and low K⁺ (4.5 mM) concentration, replicates extracellular conditions, not the intracellular environment [2]. This discrepancy can lead to misleading results, as dissociation constants (Kd) and enzyme kinetics measured in vitro can differ from their actual values inside the cell by orders of magnitude [2]. Using a cytoplasm-like buffer ensures that protein-ligand interactions and enzymatic activities are studied under more physiologically relevant conditions.

A common issue in my experiments is a discrepancy between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) results. Could buffer ionic composition be the cause?

Yes, this is a frequently encountered and often overlooked problem. Inconsistencies between BcA and CBA data can be caused by several factors, including the compound's permeability and stability. However, a major contributor is that the physicochemical conditions of standard biochemical assays are vastly different from the complex intracellular environment [2]. The ionic composition, macromolecular crowding, and viscosity of the cytoplasm can significantly alter binding affinities and reaction kinetics. Therefore, performing BcAs under conditions that mimic the intracellular milieu, including the correct K⁺/Na⁺ ratio, can help bridge the gap between BcA and CBA results [2].

How do I adjust my protein purification buffer to prevent loss of function?

Protein purification buffers are complex and should be carefully designed to maintain protein integrity and, if needed, function [28]. For proteins that are stabilized by divalent cations (e.g., Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺), it is crucial to add these cations to your growth medium and/or purification buffers. Avoid using chelating agents like EDTA in your buffers, as they will strip these essential co-factors from the protein [29]. Always check the specific requirements of your protein, as the need for co-factors, specific salt concentrations, and pH can vary greatly.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Correlation Between In Vitro and Cellular Data

Possible Cause: The use of a standard buffer (e.g., PBS) that mimics extracellular conditions for testing intracellular targets.

Solution: Replace the standard buffer with a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer.

- Protocol: Preparing a Basic Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer

- Objective: To create a buffer solution that more accurately reflects the ionic composition of the mammalian cytoplasm.

- Background: The cytoplasmic environment is characterized by a high K⁺ (~140-150 mM) and low Na⁺ (~14 mM) concentration, which is the inverse of extracellular fluid and common buffers like PBS [2].

- Materials:

- Potassium Chloride (KCl)

- Potassium Phosphate (e.g., K₂HPO₄/KH₂PO₄)

- Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂)

- HEPES or another suitable pH buffer

- Dithiothreitol (DTT) or similar reducing agent (use with caution, see note below)

- Macromolecular crowding agents (e.g., PEG, Ficoll)

- Procedure:

- Solution A (1 M HEPES, pH 7.2): Dissolve HEPES in nuclease-free water and adjust to pH 7.2 with KOH. Bring to volume.

- Final Buffer (100 mL):

- 10 mL of 1 M HEPES, pH 7.2 (Final: 100 mM)

- 7.46 g of KCl (Final: ~140 mM K⁺)

- 0.584 g of NaCl (Final: ~10-15 mM Na⁺)

- 0.203 g of MgCl₂ (Final: ~10 mM, adjust as needed)

- Add crowding agents to the desired concentration (e.g., 5-20% w/v).

- Bring to 100 mL with nuclease-free water.

- Note on Redox Potential: The cytosol is a reducing environment. While DTT or TCEP can be added (e.g., 1-5 mM) to mimic this, be aware that they may denature proteins reliant on disulfide bonds. Their use must be validated for your specific protein [2].

- Verification: Always test the stability and activity of your protein in the new buffer compared to the standard buffer to confirm improvement.

Problem: Protein Instability or Inactivity After Purification

Possible Cause: The purification buffer lacks essential stabilizers or contains inappropriate salt types and concentrations.

Solution: Systematically optimize the purification buffer composition [28].

- Protocol: Buffer Optimization for Protein Stability

- Perform a Stability Screen: Use techniques like thermofluor stability assays (differential scanning fluorimetry) or dynamic light scattering (DLS) to test the protein's stability under different buffer conditions, including various pH levels, salt types (KCl vs. NaCl), and salt concentrations [29].

- Add Stabilizing Agents: Include osmolytes and stabilizers in your storage buffer. Common examples include [28]:

- Glycerol (5-20% v/v): Helps stabilize protein structure.

- Sucrose (100-300 mM): Protects against freeze-thaw stress and aggregation [30].

- Amino Acids (e.g., Glycine) or specific co-factors (e.g., NAD+, GTP) as required by your protein.

- Select the Correct Salt: The choice of salt (e.g., (NH₄)₂SO₄, Na₂SO₄, KCl, CH₃COONH₄) can significantly impact protein stability and binding in techniques like Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) [31]. Trial and error may be necessary.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Standard Buffer vs. Cytoplasmic Ionic Environment

This table summarizes the key differences between a common laboratory buffer and the intrinsic conditions of the cytoplasm.

| Parameter | Standard PBS (Extracellular-like) | Mammalian Cytoplasm | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cation | Na⁺ (157 mM) [2] | K⁺ (~140-150 mM) [2] | Determines membrane potential; critical for transporter and channel function. |

| Na⁺ Concentration | High (157 mM) [2] | Low (~14 mM) [2] | High intracellular Na⁺ can indicate pump failure or cell stress. |

| K⁺ Concentration | Low (4.5 mM) [2] | High (~140-150 mM) [2] | Essential for enzymatic activity and maintaining cell volume. |

| Na⁺:K⁺ Ratio | ~35:1 | ~0.1:1 | A low ratio is essential for the function of a wide range of cellular processes [27]. |

| Macromolecular Crowding | Low | High (~20-30% of volume occupied) [2] | Affects ligand binding affinity, reaction rates, and protein folding. |

Experimental Workflow & Pathway

Workflow for Developing a Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for creating and validating a buffer that mimics the intracellular environment.

Cellular Pathway of Sodium-Potassium Regulation

This diagram outlines the key mechanism cells use to maintain their critical ionic gradient.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Cytoplasmic Buffer Preparation

This table lists key materials required for preparing and testing buffers designed to mimic the intracellular environment.

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Primary source of K⁺ ions to establish the high intracellular potassium concentration [2]. |

| HEPES or PIPES Buffer | pH buffering agents suitable for physiological pH ranges (e.g., 7.0-7.4), providing stable pH control. |

| Macromolecular Crowders (PEG, Ficoll) | Inert polymers used to simulate the crowded intracellular environment, which affects diffusion and binding equilibria [2]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) / TCEP | Reducing agents used to mimic the reducing redox potential of the cytoplasm. Use with caution to avoid disrupting native disulfide bonds [2]. |

| MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ | Source of Mg²⁺ ions, which are essential co-factors for many enzymes and stabilize nucleic acids and protein complexes [29]. |

| Sucrose / Trehalose | Stabilizing osmolytes that protect proteins from denaturation, aggregation, and stress during freeze-thaw cycles [30]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to purification and storage buffers to prevent proteolytic degradation of the target protein [28]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Buffer Preparation Errors

This guide addresses frequent issues researchers encounter when preparing buffer solutions, which are critical for experiments aimed at mimicking the cytoplasmic environment.

FAQ 1: Why are my buffer solutions not providing consistent pH control, leading to poor experimental reproducibility?

Inconsistent pH often stems from errors in the initial preparation method. A buffer described simply as "25 mM phosphate pH 7.0" is ambiguous and can be prepared in several ways, leading to different ionic strengths and buffering capacities [32]. To ensure consistency:

- Specify Salt Forms and Procedure: The exact procedure must be defined, including the specific salt form used (e.g., sodium dihydrogen phosphate) and the detailed pH adjustment procedure [32].

- Avoid Diluting pH-Adjusted Stock: Diluting a concentrated, pH-adjusted stock solution with water will change the final pH. For example, diluting a 2 M sodium borate stock from pH 9.4 results in a final pH of 9.33 [32]. Good practice is to prepare the buffer at its final working concentration.

- Calibrate and Use pH Meter Correctly: Ensure the pH meter is properly calibrated with fresh buffers, the electrode is clean and filled, and the measurement is taken at room temperature as pH is temperature-dependent [32].

FAQ 2: What causes peak distortion or high current in my capillary electrophoresis (CE) when using buffers?

This problem is frequently related to the buffer's ionic properties and preparation.

- Counter-Ion Selection: The counter-ion of a buffer migrates when voltage is applied, generating current. A counter-ion with a smaller ionic radius can help reduce current and prevent excessive heating. For example, switching from a potassium phosphate to an ammonium phosphate buffer can lower the operating current [32].

- Electrodispersion: Peak distortion can occur if the migration speed of the analytes and the buffer ions is very different. "Mobility matching" the buffer components to your analytes is crucial [32].

- Buffer Strength: While higher ionic strength can improve peak shape, it also increases current. It is recommended to optimize conditions to keep the current below 100 μA to prevent self-heating and instability [32].

FAQ 3: My microbial growth is inhibited in a buffered medium, even though the pH is optimal. What could be wrong?

The buffer itself might be toxic or inhibitory to your cells. This is a critical consideration when cultivating novel microbial taxa or working with sensitive cell lines.

- Buffer Toxicity: Some buffer compounds, such as Tris, can permeate cell cytoplasm and disrupt the cell's natural buffering capacity, inhibiting growth or killing cells [4].

- Incompatible Buffers: Laboratory growth media supplemented with incompatible buffers can suppress growth. For instance, some Rhodanobacter strains show poor growth at pH 5 with HOMOPIPES buffer but grow optimally at pH 4 in medium adjusted simply with HCl [4].

- Recommendation: For initial characterization and cultivation, consider using a rich medium with pH adjusted using 1 N NaOH or 1 N HCl, continuously monitoring the pH. The compatibility of any buffer should be screened before detailed physiological experiments [4].

FAQ 4: I accidentally overshot the pH while adjusting my buffer. Is it okay to readjust it back to the target value?

While possible, this practice is not ideal as it alters the buffer's final ionic strength. For a phosphate buffer pH 7.0 adjusted with concentrated phosphoric acid, overshooting and then correcting with sodium hydroxide will result in a different ionic strength compared to a buffer prepared correctly on the first attempt [32]. This can lead to higher operating currents and less precise migration times in techniques like CE [32]. It is better to discard the solution and start over for the most reproducible results.

FAQ 5: When should I measure the pH—before or after adding organic solvents or other additives?

pH should always be measured before the addition of organic solvents or other additives [32]. Adding organic solvents changes the solution's proton activity, making the pH reading inaccurate. Furthermore, additives like sulphated cyclodextrins can be acidic and will lower the pH when added [32].

Experimental Protocol: Reliable Phosphate Buffer Preparation

This protocol outlines a precise weight-based method to prepare a 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 6.8, avoiding reliance on a pH meter and ensuring high reproducibility [33].

- Principle: By mixing calculated masses of specific salt forms of phosphate, a buffer at a precise pH can be achieved without needing a pH meter for adjustment.

- Application: This phosphate buffer is commonly used in various biochemical and analytical applications to maintain a physiological pH.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit)

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Sodium Dihydrogen Phosphate Dihydrate (NaH₂PO₄·2H₂O) | Provides the acid component of the phosphate buffer system. |

| Disodium Hydrogen Phosphate 12-Hydrate (Na₂HPO₄·12H₂O) | Provides the conjugate base component of the phosphate buffer system. |

| Analytical Balance | Precisely weighs buffer components; critical for accuracy. |

| Volumetric Flask (1 L) | Brings the final solution to an exact volume for accurate molarity. |

| Purified Water | Solvent for preparing the aqueous buffer solution. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Weighing: Precisely weigh 7.8 g (50 mmol) of sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate (M.W.=156.01) and 17.9 g (50 mmol) of disodium hydrogen phosphate 12-hydrate (M.W.=358.14) [33].

- Dissolving: Transfer both salts into a clean 1 L volumetric flask. Add approximately 500 mL of purified water and swirl to dissolve the salts completely.

- Dilution to Volume: Once the salts are fully dissolved, carefully add purified water to bring the total volume to the 1 L mark on the flask.

- Mixing: Invert the sealed flask several times to ensure thorough mixing and homogeneity.

- Verification (Optional): As a quality control step, the pH can be verified using a properly calibrated pH meter. It should read approximately 6.8.

Table 1: Common Buffer Preparation Errors and Preventive Measures

| Error | Consequence | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|

| Vague buffer description [32] | Irreproducible results and ionic strength | Specify exact salt forms, concentrations, and full adjustment procedure in methods. |

| Diluting pH-adjusted stock [32] | Shift in final pH value | Prepare buffer at final working concentration. |

| pH meter misuse [32] | Incorrect pH reading | Calibrate with fresh standards; measure at room temperature; maintain electrode. |

| Overshooting pH [32] | Altered ionic strength | Discard and restart preparation for critical applications. |

| Adding buffer to toxic compounds [4] | Inhibition of cell growth or death | Screen buffer compatibility with biological system before use. |

| Measuring pH after additive addition [32] | Inaccurate pH reading | Always measure and adjust pH before adding organic solvents or other additives. |

Table 2: Selecting a Buffer for Cytoplasmic Environment Research

| Buffer Consideration | Rationale & Application |

|---|---|

| Effective Buffering Range | A buffer is most effective at resisting pH change within ±1 unit of its pKa [32]. The cytoplasmic pH is typically ~7.2, so choose a buffer with a pKa in this range (e.g., HEPES, pKa 7.5; PIPES, pKa 6.8). |

| Biological Compatibility | The buffer should be non-toxic and not form complexes with essential ions in the medium. "Good's buffers" (e.g., HEPES, MOPS) are often chosen for their biological inertness [32] [4]. |

| Ionic Strength & Conductivity | Higher ionic strength buffers can improve peak shape in separations but increase current/heat. Optimize for a balance between performance and system stability [32]. |

| Counter-Ion Effects | The counter-ion (e.g., Na⁺ vs. K⁺) can affect current and analyte migration. In some contexts, potassium salts may be preferable to better mimic the intracellular milieu [32]. |

Workflow Diagram: Troubleshooting Buffer Preparation

This workflow provides a logical pathway to diagnose and resolve common buffer-related problems in your experiments.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Practical Implementation

Q1: Why is there often a discrepancy between activity values (e.g., Kd, IC50) obtained from standard biochemical assays and cellular assays?

A1: This common discrepancy arises because standard biochemical assays are typically conducted in simplified buffers like PBS, which mimic extracellular conditions. In contrast, the intracellular cytoplasm is highly crowded, viscous, and has a distinct ionic composition (high K+, low Na+). These physicochemical differences can alter molecular diffusion, binding affinity, and enzyme kinetics, leading to measured Kd values that can be up to 20-fold different from those in cellular environments [2].

Q2: What are the key physicochemical parameters of the cytoplasmic environment that must be mimicked?

A2: An effective cytomimetic buffer should replicate these core parameters [2]:

- Macromolecular Crowding: Concentrations of 200-300 mg/mL of macromolecules to mimic the dense cellular interior [34] [2].

- Ionic Composition: High K+ (∼140-150 mM) and low Na+ (∼14 mM), reversing the ratio found in common buffers like PBS [2].

- Viscosity: Increased viscosity to match the cytoplasmic milieu, which affects molecular dynamics.

- pH: Maintained at a physiological cytosolic pH, typically around 7.4.

- Cosolvents: Components that modulate the solution's lipophilicity to mimic the hydrophobic effects inside cells.

Q3: What are the functional consequences of macromolecular crowding on enzymatic reactions in protocells?

A3: Crowding has a profound and nonlinear impact. Research in liposome-based protocells has shown that macromolecular crowding can induce a switch from reaction-controlled to diffusion-controlled kinetics. This effect is size-dependent, leading to distinct optimal crowding conditions for different processes like transcription and translation. Essentially, as crowding increases, the diffusion of large molecules and complexes (like ribosomes) can become severely restricted, thereby dictating the overall reaction rate [34].

Q4: My protein is insoluble or precipitates when I add crowding agents. How can I troubleshoot this?

A4: This is a frequent challenge. Consider these steps:

- Gradual Introduction: Do not add crowding agents directly at high concentrations. Introduce them gradually to the sample with gentle mixing.

- Agent Selection: Synthetic polymers like PEG and Ficoll create largely inert crowding based on excluded volume but lack the complex interactions of a real cytoplasm. Consider using biologically relevant crowding agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or cell lysates, which may provide a more natural environment [34] [2].

- Stabilizing Additives: Include compatible stabilizing agents like osmolytes (e.g., betaine, glycerol) in your buffer formulation.

- pH and Ionic Strength: Verify that the pH and ionic strength of your cytomimetic buffer are optimal for your specific protein, as crowding can exacerbate sensitivity to these conditions.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low or Altered Enzymatic Activity in Cytomimetic Buffers

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Greatly reduced reaction rate. | Diffusion limitation due to high viscosity and crowding. | Titrate the crowding agent to find the optimal concentration for your specific enzyme and reaction. The efficiency of gene expression, for instance, can show a nonlinear relationship with crowding level [34]. |

| Loss of protein solubility/activity. | Non-specific interactions with crowding agents or unsuitable ionic environment. | Switch the type of crowding agent (e.g., from PEG to Ficoll or a protein-based crowder). Ensure the cytomimetic buffer has the correct K+/Na+ ratio and osmolality [2]. |

| Inconsistent results between assays. | Unbuffered pH or lack of reducing environment. | Always include an appropriate buffer like HEPES. Consider adding reducing agents like DTT to mimic the cytosolic redox state, but be cautious as they may disrupt disulfide bonds [2]. |

Issue 2: Challenges in Measuring Binding Affinities (Kd)

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Kd values from cytomimetic buffers are significantly higher (weaker affinity) than in dilute buffers. | Crowding can destabilize certain complexes, particularly if the binding interface involves large conformational changes. | This may be a biologically relevant result. Validate the finding with a complementary cellular assay. |

| Kd values are significantly lower (stronger affinity) than in dilute buffers. | The excluded volume effect of crowding agents favors association reactions, making binding energetically favorable. | This is an expected effect of macromolecular crowding. Report this as the "effective affinity" under cytomimetic conditions. |

| High background noise in fluorescence-based assays. | Crowding agents can cause light scattering or increased autofluorescence. | Include proper blank controls containing the cytomimetic buffer alone. Use a detection method less susceptible to scattering, such as time-resolved fluorescence. |

Table 1: Impact of Cytomimetic Crowding on Biomolecule Diffusion [34]

| Biomolecule | Size (kDa/MDa) | Diffusion Coefficient in Dilute Conditions (μm²/s) | Diffusion Coefficient in Crowded Conditions (>250 mg/mL) (μm²/s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBDG (glucose analog) | 0.34 kDa | >26 | >26 | Negligible effect of crowding on small molecules. |

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | 27 kDa | 35.0 ± 3.6 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | ~20-fold reduction, matching in vivo measurements. |

| 70S Ribosomes | 2.7 MDa | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 0.077 ± 0.007 | ~10-fold reduction, nearly immobile at highest crowding. |

Table 2: Comparison of Standard vs. Cytomimetic Assay Conditions [2]

| Parameter | Standard Biochemical Assay (e.g., PBS) | Cytomimetic Buffer | Biological Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Composition | High Na+ (157 mM), Low K+ (4.5 mM) | High K+ (140-150 mM), Low Na+ (~14 mM) | Replicates intracellular ion gradient critical for many enzymes. |

| Macromolecular Crowding | None or very low | 200-300 mg/mL | Drastically alters reaction kinetics and binding equilibria via excluded volume effect. |

| Viscosity | Low, similar to water | Significantly elevated | Impacts diffusion rates, particularly for large complexes. |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing | Reducing (high glutathione) | Affects proteins with cysteine residues; requires careful handling. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Gene Expression in Crowded Liposome Protocells

This protocol is adapted from studies recreating crowded cytoplasm in liposomes to study cell-free gene expression [34].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Cell Lysate: The source of transcriptional and translational machinery.

- Feeding Buffer (FB): Contains amino acids (AAs), nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs), essential metabolites, and an energy source.

- Cytomimetic Salts: Mg-glutamate and K-glutamate to mimic intracellular cation composition.

- DNA Template: Linear DNA encoding the protein of interest (e.g., fluorescent protein).

- Liposome Components: Phospholipids for vesicle formation.

- Hypertonic Solution: Sucrose solution for osmotically shrinking liposomes.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Form liposomes filled with cell lysate, feeding buffer, cytomimetic salts, and the DNA template.

- Volume Reduction: Osmotically shrink the prepared liposomes by transferring them into a hypertonic sucrose solution. This step concentrates all internal components, achieving lysate concentrations from 14 mg/mL to over 390 mg/mL to vary the degree of crowding.

- Incubation: Incubate the shrunk liposomes at a controlled temperature (e.g., 30-37°C) for several hours to allow for gene expression.

- Analysis:

- Quantification: Measure the yield of the expressed protein (e.g., deCFP) using fluorescence spectroscopy.

- Diffusion Measurement: Use Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) in parallel to correlate protein synthesis efficiency with the diffusion coefficients of key components like ribosomes under identical crowding conditions.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Ligand Binding Under Cytomimetic Conditions

This protocol outlines a general approach for measuring dissociation constants (Kd) in cytomimetic buffers.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Cytomimetic Buffer: A base buffer containing high K+ glutamate (e.g., 150 mM), Mg2+ glutamate, HEPES (pH 7.4), a reducing agent (if applicable), and a chosen crowding agent (e.g., Ficoll 70, BSA, or PEG) at a defined concentration.

- Purified Target Protein.

- Ligand: A fluorescently labeled or otherwise detectable ligand.

Methodology:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare a series of cytomimetic buffers with a constant concentration of the crowding agent but varying concentrations of the ligand.

- Equilibrium Binding: Mix a fixed concentration of the purified target protein with the different ligand concentrations in the cytomimetic buffers. Allow the binding reaction to reach equilibrium.

- Separation/Measurement:

- For a fluorescent ligand, measure the signal directly (e.g., via fluorescence polarization or anisotropy change upon binding).

- For other methods, separate bound from unbound ligand (e.g., using size-exclusion spin columns or dialysis) and quantify the fractions.

- Data Analysis: Plot the concentration of bound ligand versus the free ligand concentration. Fit the data to a binding isotherm model to determine the Kd value under these cytomimetic conditions. Compare this value to one obtained in a standard buffer like PBS.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Cytomimetic Assay Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Cytomimetic Assays |

|---|---|---|

| Crowding Agents | Ficoll 70, Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), cell lysates | Mimics the high macromolecular concentration of the cytoplasm, creating excluded volume effects that influence binding and reaction rates [34] [2]. |

| Cytomimetic Salts | K-glutamate, Mg-glutamate, Potassium chloride (KCl) | Provides the high K+ / low Na+ ionic environment of the cytosol, which is critical for the proper function of many intracellular enzymes [34] [2]. |

| Physiological Buffers | HEPES, PIPES | Maintains a stable cytosolic pH (around 7.4) without introducing non-physiological ions like phosphate at high concentrations. |

| Viscosity Modifiers | Glycerol, Sucrose | Can be used to fine-tune the viscosity of the assay medium to better match the physical properties of the cytoplasmic fluid. |

| Protocell Platforms | Liposomes, Membranized Coacervate Microdroplets (MCM), Colloidosomes | Provides a physically confined compartment to study biochemical reactions in a highly controlled, crowded environment that closely mimics a synthetic cell [34] [35] [36]. |

Troubleshooting Cytomimetic Assays: Solving Common Problems and Fine-Tuning Performance

When your experimental results are inconsistent, a hidden and often overlooked culprit could be your buffer system. Biological assays are frequently conducted in simplified chemical solutions that poorly mimic the complex intracellular environment where many drug targets are located. A significant discrepancy often exists between activity values obtained from biochemical assays and those from cellular assays, which can delay research progress and drug development [2]. This technical guide will help you diagnose whether your assay inconsistencies stem from inappropriate buffer conditions or truly biological variation, with a specific focus on optimizing buffers to better replicate cytoplasmic conditions.

FAQ: Buffer Selection and Cytoplasmic Mimicry

Q: Why is there frequently a discrepancy between biochemical assay (BcA) and cell-based assay (CBA) results? A: Inconsistencies between BcAs and CBAs are common and can stem from factors like compound permeability, solubility, and specificity. However, a fundamental and often overlooked factor is the difference in physicochemical conditions. Standard assay buffers, like PBS, are designed to mimic extracellular fluid, not the intracellular cytoplasm where many drug targets reside. This mismatch in ionic composition, crowding, viscosity, and other parameters can significantly alter measured Kd values and enzymatic kinetics [2].

Q: What are the key differences between standard buffers and the cytoplasmic environment? A: The cytoplasmic environment is markedly different from standard assay buffers. The table below summarizes the critical differences you need to consider.

Table 1: Cytoplasmic vs. Standard Buffer Conditions

| Parameter | Standard Buffer (e.g., PBS) | Cytoplasmic Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Dominant Cation | High Na+ (157 mM) | High K+ (140-150 mM) |

| Potassium Level | Low K+ (4.5 mM) | Low Na+ (~14 mM) |

| Macromolecular Crowding | Minimal | High (80-200 mg/mL) |

| Viscosity | Low, like water | High due to crowding |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing | Reducing (high glutathione) |

| pH | Usually 7.4 | ~7.2 [2] |

Q: Can the buffer itself inhibit my microbial or cellular growth? A: Yes. Different buffer compounds impact microbial physiology and cell growth differently. Some exert toxic and inhibitory effects. For instance:

- Tris buffer can permeate cell cytoplasm and disturb the cell's natural buffering capacity, inhibiting or even killing cells [4].

- HOMOPIPES buffer suppressed the growth of some Rhodanobacter strains at pH 5, while the same organisms grew optimally at pH 4 in an unbuffered medium adjusted with HCl [4]. It is recommended to first screen buffer compatibility before starting physiological experiments [4].

Q: What is a common sign that my buffer is interfering with a colorimetric assay like Bradford or ELISA? A: High background is a frequent symptom. This can be caused by contaminated buffers, insufficient washing (leaving unbound enzyme), or interference from substances in your sample buffer [37] [38]. For Bradford assays specifically, a dark blue color may indicate high alkaline concentrations that raise the pH beyond the assay's limits [37].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Assay Inconsistencies

Problem: High Background Signal

- Possible Source: Insufficient washing during assay steps.

Test or Action: Increase the number of washes and incorporate a 30-second soak step between washes. If using an automated plate washer, ensure all ports are clean [38].

Possible Source: Buffer contaminated with metals, HRP, or other interfering substances.

- Test or Action: Prepare fresh buffers. Ensure all equipment (cuvettes, reagent reservoirs, plate sealers) is clean and not reused, as residual HRP can cause non-specific signal [37] [38].

Problem: Low or No Signal

- Possible Source: Buffer composition is incompatible with the assay.

Test or Action: Check for incompatible substances like detergents in your sample buffer. Dilute the sample or dialyze it into a compatible buffer. Run a standard curve in both water and your sample buffer; if the slopes differ, your buffer is interfering [37].

Possible Source: Enzyme activity is suppressed by the buffer.

- Test or Action: Certain buffers may directly inhibit enzymatic activity. Re-test your system using a rich universal laboratory growth medium with its pH adjusted using NaOH/HCl, but monitor the pH continuously. If growth or activity improves, your buffer is likely inhibitory [4].

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Experiments

- Possible Source: Variations in buffer preparation or lot-to-lot reagent inconsistency.