Breaking the Barrier: Understanding and Overcoming Challenges in GC-Rich PCR Amplification

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms that make GC-rich DNA templates challenging to amplify via standard Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

Breaking the Barrier: Understanding and Overcoming Challenges in GC-Rich PCR Amplification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the molecular mechanisms that make GC-rich DNA templates challenging to amplify via standard Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). It explores the foundational science behind template stability and secondary structure formation, details specialized methodologies and reagent choices, and offers a systematic troubleshooting guide for optimization. Further, it examines advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses of modern platforms, delivering an essential resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with complex genomic targets like promoter regions of housekeeping and tumor suppressor genes.

The GC-Rich Challenge: Unraveling the Molecular Mechanisms of PCR Failure

GC-rich templates are DNA sequences characterized by a high percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases, typically defined as regions where 60% or more of the bases are G or C [1]. While these regions constitute approximately only 3% of the human genome, they are disproportionately found in functionally significant areas, particularly gene promoter regions and other regulatory elements [1] [2]. This concentration in regulatory domains is biologically crucial, as most housekeeping genes, tumor-suppressor genes, and approximately 40% of tissue-specific genes contain high GC sequences in their promoter regions [2]. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promoter, for instance, features an extremely high GC content of up to 88%, creating significant challenges for molecular amplification techniques [3]. Understanding the prevalence and characteristics of these regions is essential for researchers investigating gene regulation, cancer biology, and pharmaceutical development, particularly when employing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based methodologies.

The Fundamental Challenges in Amplifying GC-Rich Templates

The amplification of GC-rich DNA sequences using standard PCR protocols presents unique difficulties that often lead to reaction failure, low yield, or non-specific products. These challenges stem from the intrinsic physicochemical properties of DNA and its behavior under standard amplification conditions.

Stable Hydrogen Bonding and High Melting Temperature

The primary challenge in amplifying GC-rich regions arises from the three hydrogen bonds between G-C base pairs, compared to only two hydrogen bonds between A-T base pairs [1]. This increased bond stability results in a significantly higher melting temperature (Tm) required to separate DNA strands [1]. Under standard denaturation conditions (typically 94-95°C), GC-rich templates may not fully denature, preventing primers from accessing their binding sites and ultimately leading to inefficient amplification or complete PCR failure [1] [2].

Formation of Complex Secondary Structures

GC-rich regions are structurally 'bendable' and readily form stable secondary structures such as hairpins, knots, and tetraplexes [1] [4]. These structures occur when GC-rich stretches fold onto themselves, creating physical barriers that block DNA polymerase progression during the extension phase of PCR [1]. The resulting effect is often truncated PCR products or complete stalling of the amplification process, as the polymerase cannot navigate through these complex configurations.

Competitive Annealing and Mispriming

The theoretical model based on competitive primer binding demonstrates that GC-rich templates exhibit a narrow optimal annealing efficiency window compared to normal GC content templates [2]. This phenomenon occurs because primers have increased opportunities to anneal at incorrect sites on GC-rich templates, leading to non-specific amplification and smeared products on electrophoresis gels [2]. Experimental confirmation has shown that annealing times greater than 10 seconds often yield smeared PCR products for GC-rich genes, whereas non-GC-rich templates do not display this sensitivity [2].

Table 1: Key Challenges in GC-Rich Template Amplification

| Challenge | Underlying Cause | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| High Thermal Stability | Three hydrogen bonds in G-C pairs | Incomplete denaturation at standard temperatures |

| Secondary Structure Formation | Self-complementarity of GC-rich sequences | Polymerase stalling and truncated products |

| Competitive Annealing | Multiple potential primer binding sites | Non-specific amplification and primer dimers |

| Increased Error Frequency | Thermal damage at high denaturation temperatures | Sequence mutations and decreased product fidelity |

Thermal Damage and Error Accumulation

When amplifying GC-rich templates that require higher denaturation temperatures or longer exposure to heat, the risk of thermal damage to DNA increases significantly [5]. This damage primarily occurs through three mechanisms: A+G depurination, oxidative damage of guanine to 8-oxoG, and cytosine deamination to uracil [5]. These modifications can lead to incorrect nucleotide incorporation during amplification or cause polymerase stalling at abasic sites, ultimately reducing product yield and fidelity.

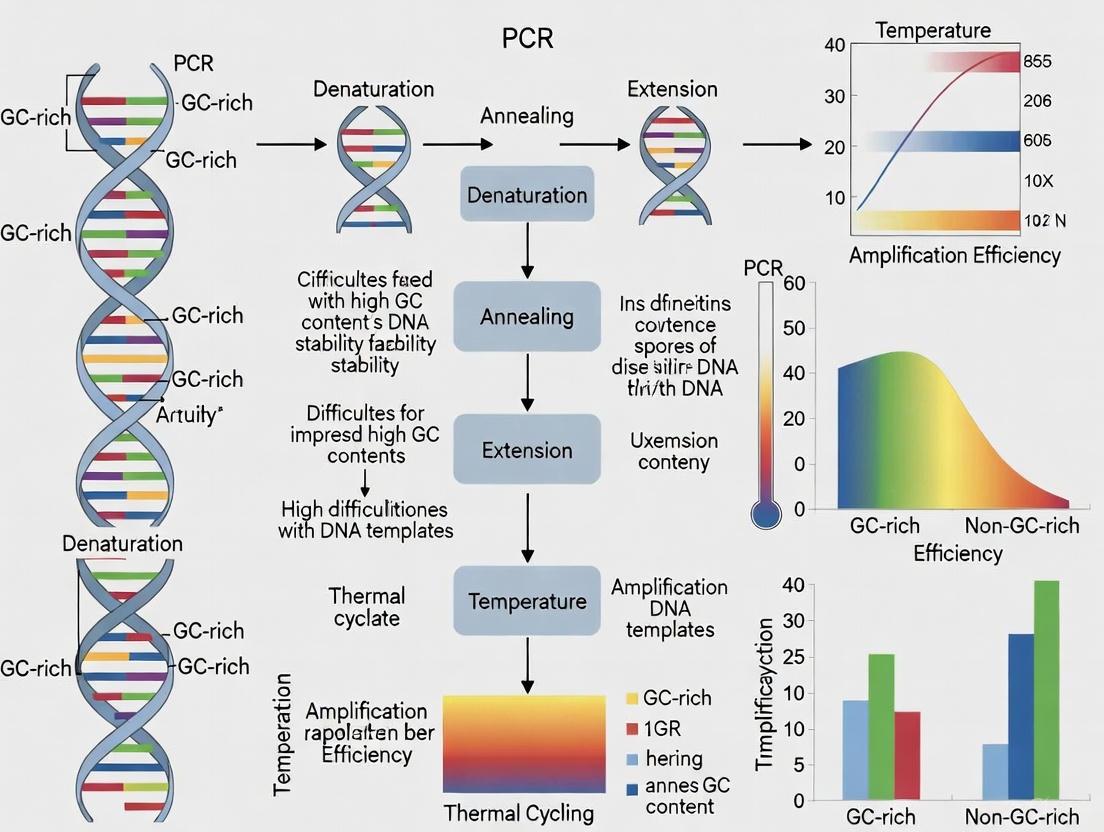

Figure 1: Mechanism-Consequence Relationships in GC-Rich PCR Amplification

Experimental Optimization Strategies and Protocols

Successfully amplifying GC-rich templates requires a systematic, multi-pronged optimization approach targeting reaction components, thermal cycling parameters, and enzymatic selection. The following strategies have demonstrated efficacy across various challenging templates, including the EGFR promoter and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits.

Polymerase Selection and Buffer Composition

Choosing an appropriate DNA polymerase is critical for successful GC-rich amplification. Standard Taq polymerase often fails with difficult templates, while specialized polymerases with proofreading capabilities and GC-enhanced buffer systems significantly improve results [1] [4]. For example, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase provides >280 times the fidelity of Taq and can be supplemented with a GC enhancer for targets up to 80% GC content [1]. Similarly, OneTaq DNA Polymerase is supplied with both standard and GC buffers specifically designed for difficult amplicons [1].

Experimental Protocol: Polymerase Comparison

- Set up identical PCR reactions with varying DNA polymerases: Standard Taq, OneTaq with GC Buffer, and Q5 with GC Enhancer

- Use a GC-rich control template (e.g., EGFR promoter fragment)

- Maintain consistent cycling conditions: 98°C initial denaturation for 30s, 35 cycles of 98°C for 10s, 63°C for 20s, 72°C for 30s/kb

- Analyze products on 2% agarose gel for yield and specificity [3] [1]

Magnesium Ion Concentration and PCR Additives

Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂) concentration significantly influences PCR efficiency, particularly for GC-rich templates. As a essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity, Mg²⁺ concentration must be carefully optimized, typically requiring 1.5 to 2.0 mM for GC-rich targets [3]. Additionally, incorporating PCR additives that disrupt secondary structures is often necessary. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 5% concentration has proven effective for EGFR promoter amplification, while betaine (also known as trimethylglycine) can be used alone or in combination with DMSO [3] [4].

Experimental Protocol: Mg²⁺ and Additive Titration

- Prepare master mix with all components except MgCl₂

- Aliquot reactions and add MgCl₂ to final concentrations of 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 mM

- Test separate reaction sets with: no additives, 5% DMSO, 1M betaine, and DMSO/betaine combination

- Use gradient PCR to simultaneously test annealing temperatures from 60-70°C

- Identify optimal conditions based on product yield and specificity [3] [1]

Thermal Cycling Parameter Optimization

GC-rich templates require precise thermal cycling conditions that balance complete denaturation with polymerase stability. Research indicates that shorter annealing times (3-6 seconds) are often more effective for GC-rich amplification than standard 30-second annealing steps [2]. Additionally, implementing a two-step PCR protocol (combining annealing and extension) at slightly reduced extension temperatures (65°C instead of 72°C) can improve results for particularly challenging templates [6].

Experimental Protocol: Thermal Cycling Optimization

- Program thermocycler with shortened denaturation (5-10 seconds) and extension (15-30 seconds/kb) times

- Test annealing times from 3-20 seconds at the optimal annealing temperature

- Implement a touchdown protocol starting 5°C above calculated Tm and decreasing 1°C every cycle for 5 cycles

- For extremely resistant templates, consider using a 2-step PCR with extension at 65°C for 1.5 min/kb [2] [6]

Table 2: Optimized PCR Components for GC-Rich Amplification

| Component | Standard PCR | GC-Rich Optimized | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerase | Standard Taq | Specialized (Q5, OneTaq) with GC Enhancer | Better processivity through secondary structures |

| MgCl₂ Concentration | 1.5 mM | 1.5-2.0 mM (target-specific) | Balancing enzyme activity and primer specificity |

| Additives | None | 5% DMSO, 1M Betaine, or combination | Disrupts secondary structures, reduces Tm |

| Denaturation Temperature | 94-95°C | 98°C | More complete strand separation |

| Annealing Time | 30 seconds | 3-10 seconds | Reduces mispriming and competitive binding |

| Template Concentration | Varies | ≥2 μg/ml | Ensures sufficient target molecules [3] |

Primer Design Considerations for GC-Rich Targets

Careful primer design is paramount for successful GC-rich amplification. Primers with high self-dimer free energy values (ΔG) tend to promote non-specific amplification. Introducing null mutations to bring ΔG levels below -5.0 kcal/mol can significantly improve specificity [7]. Additionally, increasing primer length to 25-30 nucleotides helps enhance binding specificity despite the challenging template composition [4].

Figure 2: Systematic Optimization Workflow for GC-Rich PCR

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successfully navigating GC-rich amplification challenges requires access to specialized reagents and materials specifically formulated for difficult templates. The following toolkit compiles essential solutions referenced in the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GC-Rich Amplification

| Reagent/Material | Specific Examples | Function in GC-Rich PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | OneTaq DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0480), Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0491) | Enhanced processivity through secondary structures; higher fidelity [1] |

| GC Enhancers | OneTaq High GC Enhancer, Q5 High GC Enhancer | Proprietary additive mixtures that inhibit secondary structure formation [1] |

| PCR Additives | DMSO (5%), Betaine (1M), 7-deaza-dGTP | Reduce secondary structures, decrease melting temperature, improve yield [3] [4] [2] |

| Buffer Systems | GC Buffer (NEB), Phusion GC Buffer | Specially formulated with optimal salt and pH conditions for GC-rich targets |

| Thermostable Polymerases | KOD Hot Start Polymerase, Phusion High-Fidelity | Withstand higher denaturation temperatures needed for GC-rich templates [2] |

| Rapid Cycler Systems | PCRJet thermocycler | Minimize thermal damage through fast temperature transitions [2] [5] |

Amplifying GC-rich templates from gene promoters and regulatory regions remains technically challenging but achievable through systematic optimization. The difficulty stems from fundamental molecular properties including stable hydrogen bonding, propensity for secondary structure formation, and competitive primer annealing. A successful amplification strategy requires a multipronged approach involving specialized polymerases with GC enhancers, optimized Mg²⁺ concentrations, structure-disrupting additives like DMSO and betaine, and carefully calibrated thermal cycling parameters with shortened annealing times [4] [7]. The implementation of a combination strategy addressing all these factors simultaneously—rather than sequential single-parameter optimization—has proven most effective for challenging targets such as the EGFR promoter with 88% GC content and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits with 65% GC content [3] [4]. This comprehensive approach enables researchers to consistently amplify these biologically critical regions, facilitating advanced studies in gene regulation, biomarker discovery, and targeted drug development.

In molecular biology and genetics, GC-content refers to the percentage of nitrogenous bases in a DNA or RNA molecule that are either guanine (G) or cytosine (C). This fundamental property significantly influences DNA thermostability and presents substantial challenges for techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR), particularly when amplifying GC-rich templates (those exceeding 60% GC content) [8]. The core of this challenge lies in the stronger bonding nature of G-C base pairs compared to A-T pairs, creating a fundamental dilemma for researchers: while GC-rich regions provide biological stability, they also create technical barriers that must be overcome through optimized experimental approaches.

This whitepaper examines the biophysical principles underlying the thermostability of GC-rich DNA, details the specific challenges encountered in PCR amplification, and provides evidence-based solutions for researchers working in genomics, diagnostic development, and therapeutic discovery. Understanding these principles is particularly crucial when studying promoter regions of housekeeping and tumor suppressor genes, which are often GC-rich, as well as genomes of organisms like Mycobacterium bovis (with GC content >60%) where standard PCR protocols frequently fail [9] [10].

The Biophysical Basis of G-C Pair Stability

Hydrogen Bonding and Base Stacking Interactions

The stability of DNA double helices with high GC-content stems from two primary molecular interactions, with the contribution of hydrogen bonds often being misunderstood in conventional wisdom.

Hydrogen Bonding: Guanine and cytosine undergo specific hydrogen bonding with each other through three hydrogen bonds, denoted as G≡C. In contrast, adenine-thymine pairs in DNA (and adenine-uracil in RNA) are connected by only two hydrogen bonds, represented as A=T or A=U [8]. This additional hydrogen bond in GC pairs contributes to their stability, though its role is sometimes overemphasized.

Base Stacking Interactions: Contrary to popular belief, research indicates that hydrogen bonds themselves do not have a particularly significant impact on molecular stability, which is instead caused mainly by molecular interactions of base stacking [8]. More favorable stacking energy exists for GC pairs than for AT or AU pairs because of the relative positions of exocyclic groups, creating a correlation between base stacking order and the thermal stability of the molecule as a whole [8].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of DNA Base Pair Interactions

| Feature | G-C Base Pair | A-T Base Pair |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bonds | 3 | 2 |

| Bond Notation | G≡C | A=T |

| Base Stacking Energy | More favorable | Less favorable |

| Relative Contribution to Stability | Major (stacking) | Minor (stacking) |

| Thermal Resistance | Higher | Lower |

Temperature Dependence of Hydrogen Bonds

The relationship between hydrogen bond strength and temperature follows a quantifiable pattern that directly impacts DNA thermostability. Recent single-molecule studies have demonstrated a significant decline in H-bond intrinsic strength as temperature increases [11]. This relationship can be expressed through a nonlinear correlation with the empirical equation: ΔG* = 7.88 - 1.34ln(T - 251.64), where ΔG* represents H-bond intrinsic strength and T is temperature in Kelvin [11].

High-resolution NMR studies of protein hydrogen bonds provide additional insights into this temperature dependence, showing that hydrogen bonds undergo thermal expansion with an average linear thermal expansion coefficient of 1.7×10⁻⁴/K for NH→O hydrogen bonds [12]. This expansion leads to a global weakening of hydrogen bond scalar couplings as temperature increases, directly affecting the thermal stability of molecular structures.

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Relationships

Measuring DNA Thermostability

The thermostability conferred by GC content is quantitatively expressed through DNA melting temperature (Tm), the temperature at which half of the DNA duplexes separate into single strands [13]. For short DNA sequences, the Wallace rule provides a practical formula for approximating Tm: Tm ≈ 2 × (number of A-T pairs) + 4 × (number of G-C pairs) [13]. This rule highlights why GC content—rather than AT content—is the primary determinant of DNA melting temperature, as G-C pairs contribute approximately twice as much to the melting temperature compared to A-T pairs.

The absorbance of DNA at 260 nm increases sharply when double-stranded DNA separates into single strands upon sufficient heating, providing a spectrophotometric method for determining melting temperature and consequently GC-ratio [8]. For large numbers of samples, flow cytometry provides an efficient protocol for determining GC-ratios [8].

Table 2: Melting Temperature Characteristics of DNA with Varying GC Content

| GC Content Range | Melting Temperature | Stability Classification | PCR Difficulty |

|---|---|---|---|

| <40% | Lower | Less stable | Minimal |

| 40-60% | Moderate | Moderate stability | Standard protocols usually sufficient |

| >60% | Higher | Highly stable | Challenging, requires optimization |

| >70% | Significantly higher | Extremely stable | Very difficult, specialized methods needed |

Biological Significance of GC-Rich Regions

The distribution of GC-rich regions in genomes is non-random and functionally significant. In complex organisms, variations in GC-ratio result in a mosaic-like formation with islet regions called isochores [8]. These GC-rich isochores typically include many protein-coding genes, making determination of GC-ratios valuable for mapping gene-rich genomic regions [8].

The length of a gene's coding region is directly proportional to higher G+C content, partly because stop codons have a bias towards A and T nucleotides—thus shorter sequences exhibit higher AT bias [8]. This relationship has important implications for gene prediction and annotation in genomic studies.

The PCR Amplification Challenge

Mechanistic Obstacles in GC-Rich Amplification

Amplifying GC-rich templates by PCR presents multiple technical hurdles that often lead to failed reactions or poor yields:

Strong Hydrogen Bonding: The triple-bond nature of G≡C pairs creates enhanced thermostability, requiring more energy to separate DNA strands during the denaturation step of PCR [9]. This often necessitates higher denaturation temperatures that can compromise polymerase activity over multiple cycles.

Secondary Structure Formation: GC-rich regions are 'bendable' and readily form stable secondary structures like hairpin loops [9]. These structures block polymerase progression and result in shorter, incomplete amplification products. The stability of these secondary structures persists at standard PCR denaturation temperatures, creating persistent obstacles to amplification.

Primer-Related Issues: Primers designed for GC-rich templates tend to form self- and cross-dimers as well as stem-loop structures that impede the DNA polymerase [14]. GC-rich sequences at the 3' end of primers can also lead to mispriming, reducing amplification specificity and efficiency.

Compounding Factors in PCR Failure

The challenges of GC-rich amplification are compounded by several additional factors:

Polymerase Stalling: Many conventional DNA polymerases stall at the complex secondary structures formed by GC-rich sequences [9]. This stalling results in truncated amplification products and reduced yields.

Non-specific Amplification: The strong binding affinity in GC-rich regions can lead to non-specific primer binding, particularly when magnesium concentrations are suboptimal [9]. This manifests as multiple bands on agarose gels rather than a single clean product.

Resistance to Denaturation: GC-rich templates resist complete denaturation at standard temperatures (92-95°C), making it difficult for primers to access their binding sites [14]. While increasing denaturation temperature seems logical, temperatures exceeding 95°C can accelerate polymerase denaturation throughout PCR cycling.

Methodological Approaches and Solutions

Optimized Experimental Protocols

Successful amplification of GC-rich regions requires systematic optimization of PCR components and conditions:

Polymerase Selection: Standard Taq polymerase often underperforms with GC-rich templates. Switching to specially engineered polymerases such as Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase or OneTaq DNA Polymerase can dramatically improve results [9]. These enzymes are specifically optimized for challenging amplicons, with some capable of amplifying templates with up to 80% GC content when used with specialized enhancers.

Magnesium Concentration Optimization: Magnesium is a critical cofactor for polymerase activity and primer binding [9]. Testing MgCl₂ concentrations in 0.5 mM increments between 1.0 and 4.0 mM can identify the optimal concentration that balances specificity with yield. Excessive magnesium promotes non-specific binding, while insufficient concentrations reduce polymerase activity.

PCR Additives: Incorporating certain additives can significantly improve GC-rich amplification:

- Structure-disrupting agents: DMSO, glycerol, and betaine reduce secondary structure formation [9] [14].

- Specificity enhancers: Formamide and tetramethyl ammonium chloride increase primer annealing stringency [9].

- Nucleotide analogs: 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine, a dGTP analog, can improve PCR yield of GC-rich regions, though it doesn't stain well with ethidium bromide [9].

Temperature Modifications: Adjusting thermal cycling parameters can overcome several GC-related challenges:

- Higher denaturation temperatures (up to 95°C) help separate stubborn secondary structures, particularly when used for the first few cycles [14].

- Slower ramp rates between temperatures improve amplification efficiency for difficult templates [10].

- Two-step PCR protocols that combine annealing and extension at higher temperatures can enhance performance for long GC-rich targets [10].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for optimizing GC-rich PCR amplification. This decision pathway illustrates the multidimensional approach required for successful amplification of difficult templates.

Advanced and Alternative Methods

When standard optimization fails, several advanced approaches can overcome extreme GC challenges:

Slow-down PCR: This method uses a dGTP analog (7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine) in the PCR mixture combined with a standardized cycling protocol featuring lowered ramp rates and additional cycles [14]. The modified nucleotides disrupt the standard bonding patterns, facilitating amplification.

Base-Modified PCR: A sophisticated approach involves substituting dATP with dDTP (diaminopurine) and dGTP with dITP (inosine) to inverse the natural hydrogen bonding rule [15]. This conversion allows selective amplification of GC-rich alleles that would otherwise be impossible to target specifically.

Controlled Heat Denaturation: Incorporating a 5-minute heat denaturation step at 98°C in low-salt buffer before cycling can significantly improve sequencing and amplification through difficult regions [16]. This extended denaturation helps overcome the resistance of GC-rich templates to strand separation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GC-Rich Amplification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | Commercial Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Engineered for processivity through difficult structures | Ideal for long or GC-rich amplicons; >280x fidelity of Taq | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [9] |

| GC Enhancers/Buffers | Specialized formulations with multiple additives | Inhibit secondary structure; increase primer stringency | OneTaq GC Buffer, Q5 High GC Enhancer [9] |

| Structure-Disrupting Additives | Reduce secondary structure formation | DMSO typically used at 2-10%; betaine concentrations vary | DMSO, glycerol, betaine [9] [17] |

| Modified Nucleotides | Alter hydrogen bonding properties | Enable alternative PCR methods; inverse bonding rules | dITP, dDTP, 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine [15] |

| Magnesium Chloride | Cofactor for polymerase activity | Concentration critical; requires optimization | Standard component of PCR buffers [9] |

| Blood DNA Extraction Kits | Resistance to inhibitors in complex samples | Direct amplification from blood possible | Q5 Blood Direct Master Mix [9] |

The hydrogen bond dilemma presented by G-C pairs represents both a fundamental biophysical phenomenon and a practical laboratory challenge. While the triple hydrogen bonds of G≡C pairs contribute to DNA thermostability, the enhanced stability primarily stems from more favorable base stacking interactions in GC-rich sequences. This understanding informs the development of effective strategies for amplifying difficult GC-rich templates, which are particularly relevant in studying gene promoters, microbial genomes, and other biologically significant regions.

Successful navigation of the GC-rich amplification challenge requires a multifaceted approach incorporating specialized enzymes, optimized reaction conditions, and sometimes innovative methodological adaptations. The solutions outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with an evidence-based framework for overcoming one of molecular biology's persistent technical obstacles, enabling more reliable genetic analysis across diverse applications from basic research to diagnostic development.

As genomic technologies continue to advance and researchers encounter increasingly complex genetic targets, the principles governing GC-content thermostability and the methodological workarounds for challenging templates will remain essential knowledge for the scientific community working at the forefront of genetic research and biotechnology innovation.

The formidable challenge of amplifying GC-rich DNA templates by PCR is a universally recognized hurdle in molecular biology. Conventional wisdom often attributes the heightened stability of these sequences primarily to the triple hydrogen bonds of G-C base pairs, in contrast to the double bonds of A-T pairs. While this contribution is valid, it is an incomplete picture. A more profound, dominant force governing DNA duplex stability is base stacking interactions [14]. These interactions, arising from the overlap of π-orbitals in adjacent nitrogenous bases, are the major contributors to the thermodynamic stability of DNA. The dense, rigid arrangement of guanine and cytosine bases in GC-rich regions results in exceptionally strong stacking forces, creating a highly stable structure that is inherently resistant to denaturation. This fundamental biophysical principle explains why extremophiles, such as Thermus thermophilus, possess GC-rich genomes to withstand high-temperature environments and why promoter regions of highly expressed genes in humans are often AT-rich for easier access [14]. This whitepaper delves into the critical role of base stacking, moving beyond the simplistic hydrogen bond model, to frame the intrinsic difficulties of GC-rich PCR within a broader, more accurate thermodynamic context.

The Molecular Mechanisms Underpinning PCR Challenges

The strong base stacking energies in GC-rich sequences manifest in several specific technical challenges that can lead to PCR failure, characterized by blank gels, nonspecific smearing, or truncated products.

Elevated Thermal Stability and Secondary Structure Formation

The primary consequence of enhanced base stacking is a significant increase in the DNA's melting temperature ((T_m)). This necessitates higher denaturation temperatures during PCR, which can approach the functional limits of standard DNA polymerases, potentially leading to enzyme denaturation over multiple cycles [14]. Furthermore, the same stacking forces that stabilize the double helix also promote the formation of persistent, stable secondary structures. Single-stranded, GC-rich regions can fold back onto themselves, forming hairpin loops, knots, and tetraplexes that are exceptionally stable and do not melt efficiently at standard denaturation temperatures (e.g., 92-95°C) [18] [4]. These structures physically block the procession of the DNA polymerase, resulting in incomplete or truncated synthesis products.

Impeded Primer Annealing and Enzyme Processivity

The resistance of GC-rich templates to denaturation means that the target sites for primers may not be fully accessible during the annealing step of the PCR cycle. This forces primers to compete with the template's own intra-strand secondary structures, drastically reducing annealing efficiency. Moreover, the primers themselves, if also GC-rich, are prone to forming self-dimers or cross-dimers through their own strong stacking interactions, further reducing the pool of available primers for specific amplification [18] [19]. The cumulative effect is a significant reduction in the specificity and yield of the amplification reaction.

Table 1: Summary of PCR Challenges from Strong Base Stacking

| Molecular Mechanism | Direct Consequence | Observed PCR Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced Thermal Stability | Elevated melting temperature ((T_m)) | Incomplete template denaturation |

| Secondary Structure Formation | Stable hairpins & intra-strand structures | Polymerase stalling; truncated products |

| Impaired Primer Accessibility | Reduced primer-template annealing | Low or no amplification yield |

| Primer Self-Complementarity | Primer-dimer formation & mispriming | Nonspecific amplification; reduced efficiency |

Quantitative Analysis of DNA Folding Thermodynamics

Accurately predicting the stability of DNA secondary structures is crucial for designing successful PCR experiments, particularly for difficult targets. For decades, nearest-neighbor models have been the gold standard for this task. These models operate on the principle that the total free energy of a DNA duplex can be calculated by summing the free energy contributions of all adjacent base-pair stacks, rather than considering individual base pairs in isolation [20]. This approach inherently captures the profound effect of base stacking on overall stability.

However, traditional nearest-neighbor models have been limited by a relative scarcity of high-quality experimental thermodynamic data, especially for non-canonical structures like mismatches, bulges, and various hairpin loops. This data bottleneck has historically resulted in prediction inaccuracies. Recent technological advancements are overcoming this hurdle. The development of high-throughput methods like Array Melt has enabled the simultaneous measurement of equilibrium stability for millions of DNA hairpins [20]. This massive-scale data generation allows for the derivation of refined, more accurate thermodynamic parameters.

Table 2: Key Parameters from High-Throughput DNA Folding Studies

| Parameter | Traditional Model (SantaLucia 2004) | High-Throughput Informed Models (e.g., dna24) |

|---|---|---|

| Sequences for WC Parameters | 108 sequences for 12 parameters | Data from 27,732 two-state variants [20] |

| Data for Mismatches/Bulges | 174 sequences for 44 parameters | Massively expanded dataset across multiple scaffolds |

| Model Scope | Struggles with complex motifs | Improved accuracy for hairpin loops, mismatches, bulges |

| Application | Standard primer design | Enhanced prediction for qPCR, DNA origami, hybridization probes |

These improved models, including a NUPACK-compatible model (dna24) and graph neural network (GNN) models, demonstrate significantly higher accuracy in predicting DNA folding thermodynamics. They are better equipped to handle the diverse sequence dependence of structural motifs beyond simple Watson-Crick pairs, leading to more effective in silico design of PCR primers and other oligonucleotide-based tools [20].

Diagram 1: Workflow for deriving improved DNA folding models from high-throughput data.

Experimental Strategies to Overcome Base Stacking Effects

Overcoming the challenges posed by strong base stacking requires a multipronged experimental approach that targets the underlying thermodynamic barriers.

Strategic Use of PCR Additives

Organic additives are a primary tool for disrupting the stable structures formed by GC-rich sequences. They function through distinct mechanisms to homogenize the reaction environment and lower melting temperatures.

- Betaine (1-2 M): Also known as trimethylglycine, betaine is a zwitterion that acts as a stabilizing osmolyte. It penetrates the DNA duplex and homogenizes the base pair stability by reducing the disparity in melting temperature between GC-rich and AT-rich regions. This helps to prevent the formation of secondary structures and promotes more uniform amplification [4] [21].

- DMSO (2-10%): Dimethyl sulfoxide is a polar aprotic solvent that disrupts the hydrogen bonding network and reduces the dielectric constant of the solution. This effectively lowers the overall melting temperature of the DNA, facilitating the denaturation of stable secondary structures that would otherwise impede the polymerase [21].

- Alternative Additives: Recent studies have identified ethylene glycol (1.075 M) and 1,2-propanediol (0.816 M) as highly effective additives. In a systematic evaluation of 104 GC-rich human genomic amplicons, 1,2-propanediol successfully rescued 90% of the targets, outperforming betaine (72%) [22]. The exact mechanism differs from betaine, potentially involving differential affinity to single-stranded versus double-stranded DNA.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of PCR Additives for GC-Rich Amplification

| Additive | Typical Working Concentration | Primary Proposed Mechanism | Reported Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betaine | 1 M - 2 M | Homogenizes base pair stability; reduces (T_m) disparity | 72% of 104 GC-rich amplicons [22] |

| DMSO | 2% - 10% | Disrupts H-bonding; lowers DNA (T_m) | Often used in combination [4] |

| Ethylene Glycol | 1.075 M | Reduces DNA (T_m); mechanism distinct from betaine | 87% of 104 GC-rich amplicons [22] |

| 1,2-Propanediol | 0.816 M | Reduces DNA (T_m); mechanism distinct from betaine | 90% of 104 GC-rich amplicons [22] |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | Partial substitution for dGTP | Analog that disrupts Hoogsteen base pairing | Improves yield of GC-rich regions [18] |

Polymerase Selection and Buffer Optimization

The choice of DNA polymerase is critical. Standard Taq polymerase often stalls at the complex secondary structures stabilized by base stacking. High-fidelity polymerases with proofreading activity, such as Q5 (NEB) or Phusion, are engineered for enhanced processivity and are more capable of navigating through these obstructions [18] [4]. Furthermore, many manufacturers offer specialized polymerases and companion buffers specifically formulated for GC-rich templates. These systems often include proprietary GC Enhancers, which are optimized mixtures of additives that inhibit secondary structure formation and increase primer stringency, enabling robust amplification of sequences with up to 80% GC content [18] [23].

Cycling Parameter and Reaction Condition Adjustments

Fine-tuning the physical parameters of the PCR cycle is essential. A strategic increase in denaturation temperature (e.g., to 98°C) for the first few cycles can help melt persistent secondary structures, though care must be taken to avoid rapid enzyme inactivation [14]. Employing a temperature gradient to optimize the annealing temperature ((T_a)) is crucial to balance specificity and yield. Additionally, the concentration of magnesium ions (Mg²⁺), a essential cofactor for polymerase activity, must be carefully titrated. A gradient from 1.0 mM to 4.0 mM in 0.5 mM increments is recommended to find the optimal concentration that supports enzyme activity without promoting non-specific amplification [18] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for GC-Rich PCR

Success in amplifying GC-rich templates relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools designed to counteract the effects of strong base stacking.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GC-Rich Amplification

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Proofreading activity; enhanced processivity through secondary structures. | Q5 High-Fidelity (NEB), Phusion (Invitrogen) [18] [4] |

| Specialized GC Buffer | Optimized buffer containing salts and additives to destabilize secondary structures. | OneTaq GC Buffer (NEB), GC-Rich Enhancer (ThermoFisher) [18] [14] |

| Betaine | Zwitterionic additive; homogenizes base pair stability, reduces (T_m) differential. | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Scientific [4] [21] |

| DMSO | Polar aprotic solvent; disrupts hydrogen bonding, lowers DNA (T_m). | Common laboratory reagent [21] |

| Ethylene Glycol / 1,2-Propanediol | Alternative additives; effectively reduce DNA (T_m) via distinct mechanisms. | Common laboratory reagents [22] |

| 7-deaza-dGTP | dGTP analog; incorporated into DNA to disrupt stable secondary structures. | Roche, Sigma-Aldrich [18] |

| Tm Calculator | Web tool for accurate primer (Tm) and (Ta) calculation, accounting for enzyme/buffer. | NEB Tm Calculator, ThermoFisher Tm Calculator [18] |

Integrated Experimental Protocol: A Case Study

A practical application of these principles is demonstrated in a study optimizing the PCR amplification of GC-rich nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits from invertebrates [17] [4]. The target genes, Ir-nAChRb1 (65% GC) and Ame-nAChRa1 (58% GC), with open reading frames of 1743 bp and 1884 bp respectively, failed to amplify under standard PCR conditions.

Methodology:

- Polymerase Screening: Multiple high-fidelity DNA polymerases were evaluated, including Platinum SuperFi and Phusion, which are known for their robustness with complex templates [4].

- Additive Optimization: Additives including DMSO (5%) and Betaine (1 M) were tested both individually and in combination to assess their synergistic effects on disrupting secondary structures.

- Thermal Cycling Adjustments: A combination of touchdown PCR and adjusted denaturation temperatures was employed. The annealing temperature was optimized using a gradient PCR protocol.

- Primer Design: Primers were designed with careful attention to length (18-24 bp), melting temperature (55-70°C), and avoidance of self-complementarity to minimize secondary structure formation in the primers themselves [4] [19].

Outcome: The tailored protocol, which incorporated a combination of organic additives (DMSO and betaine), an increased concentration of a high-fidelity DNA polymerase, and optimized annealing temperatures, successfully amplified the challenging GC-rich targets. This underscores the importance of a multipronged optimization strategy when dealing with sequences dominated by strong base stacking interactions [17] [4].

Diagram 2: Logical relationship between the problem of base stacking and the strategic solutions for successful PCR.

The difficulty of amplifying GC-rich templates by PCR cannot be fully understood through the lens of hydrogen bonding alone. The critical role of base stacking interactions provides a more complete and mechanistically accurate explanation for the exceptional thermodynamic stability of these sequences. This understanding, in turn, directly informs rational experimental design. Overcoming these challenges requires a integrated strategy that targets the fundamental biophysics: employing specialized polymerases and buffers, utilizing strategic additives like betaine, DMSO, or next-generation alternatives such as 1,2-propanediol, and meticulously optimizing reaction conditions. As high-throughput methods continue to refine our predictive models of DNA folding, the scientific community is better equipped than ever to design effective protocols, ensuring that GC-rich sequences are no longer an insurmountable barrier in molecular biology and drug development research.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet the amplification of guanine-cytosine (GC)-rich templates (typically defined as sequences with >60% GC content) presents persistent challenges for researchers [24] [23]. These difficulties arise from the fundamental biophysical properties of DNA that favor the formation of stable secondary structures—primarily hairpins and loops—which can physically impede polymerase progression and lead to amplification failure [25] [26]. Understanding these structures is crucial not only for improving molecular techniques but also for appreciating their biological significance, as GC-rich regions are often found in gene promoters, including those of housekeeping and tumor suppressor genes [24] [23].

The core issue lies in the base-pairing stability of GC-rich sequences. Unlike adenine-thymine (A-T) pairs, which form two hydrogen bonds, G-C pairs form three hydrogen bonds, creating a more thermostable duplex [24]. This increased stability, combined with base-stacking interactions, results in DNA that requires more energy to denature [14]. More critically, single-stranded GC-rich regions readily fold into complex, intramolecular secondary structures that are highly resistant to denaturation at standard PCR temperatures, causing DNA polymerases to stall and resulting in incomplete or failed amplification [25] [14] [26]. This technical guide explores the mechanisms behind secondary structure formation, their impact on polymerase function, and provides evidence-based strategies for successful amplification of these challenging templates.

Molecular Mechanisms: How Secondary Structures Impede Amplification

Types of Problematic DNA Structures

GC-rich DNA sequences are prone to forming several types of stable secondary structures that interfere with PCR. The most common is the hairpin (or stem-loop) structure, which occurs when a single-stranded DNA molecule folds back on itself to form a complementary double-helical stem capped by an unpaired loop [27] [26]. These structures are exceptionally stable in GC-rich regions because their stems are reinforced by the triple hydrogen bonds of G-C base pairs.

In addition to canonical hairpins, GC-rich repeats can form more complex structures. G-quadruplexes (G4) are higher-order structures formed in nucleic acid sequences that are rich in guanine, where four guanine bases assemble in a planar arrangement through Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding [25]. Similarly, i-motifs are structures formed by cytosine-rich sequences under slightly acidic conditions [25]. The formation of these structures is not merely a theoretical concern; empirical studies have documented precise sequencing stops at the boundaries of predicted hairpin clusters, providing direct evidence of their disruptive effects [26].

The Biophysical Basis of Structural Stability

The pronounced stability of GC-rich secondary structures stems from both hydrogen bonding and base-stacking interactions. While the triple hydrogen bonds of G-C pairs contribute significantly to thermal stability, the primary stabilization force actually comes from base-stacking interactions between adjacent nucleotide pairs [14]. These stacking interactions create a thermodynamic environment where structured DNA remains folded even at elevated temperatures used in standard PCR denaturation steps (typically 92-95°C).

The stability of these structures can be quantitatively predicted by calculating their minimum free energy (MFE), with more negative values indicating greater stability [26]. Software tools such as RNAfold and UNAfold can model these structures and predict the specific hairpins most likely to cause polymerase stalling [26]. Experimental data has confirmed that polymerase-resistant regions correspond precisely to sequences predicted to form tight clusters of hairpins with high base-pairing probabilities [26].

Direct Evidence of Polymerase Stalling at Structured DNA

High-throughput studies have systematically quantified how secondary structures impede DNA synthesis. One comprehensive analysis employed a primer extension assay with a library of 20,000 structured sequences to monitor the kinetics of DNA synthesis through various STR permutations [25]. The researchers computed a stall score (σ)—the ratio of sequences in stalled versus fully extended products—which revealed that structured DNA sequences consistently caused polymerase arrest.

The biological significance of these findings is substantial. Polymerase stalling at DNA structures induces error-prone DNA synthesis, which constrains STR expansion in genomes and contributes to their evolutionary behavior [25]. This mechanistic insight explains why structured STRs exhibit lower relative abundance and shorter length in eukaryotic genomes, suggesting they are generally deleterious [25].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of DNA Secondary Structures on Polymerase Function

| Structural Feature | Experimental Measure | Impact on Amplification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin clusters | Precise sequencing stops at boundaries | Complete PCR failure across hairpin region | [26] |

| G-quadruplex (G4) motifs | ~70% of signal in stalled products | Severe inhibition of polymerase progression | [25] |

| High GC content (>60%) | Increased stall score (σ) | Reduced amplification efficiency and yield | [25] [28] |

| Structured STRs | Lower relative genomic abundance | Shorter length constraints in genomes | [25] |

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Documented Cases of Amplification Failure

Research has provided compelling case studies of how secondary structures disrupt molecular biology techniques. One investigation of the mouse Foxd3 locus identified a 370-nucleotide segment that was resistant to polymerase read-through during both PCR and sequencing reactions [26]. This region, located just upstream of the 5' untranslated region, was also impossible to manipulate using BAC recombineering strategies. The segment was found to be GC-rich (61% GC content) and was predicted by minimum free energy algorithms to form a tight cluster of hairpin structures [26].

Sequencing reads from primers flanking this segment consistently stopped at the same positions, defining the precise boundaries of the polymerase-resistant region [26]. However, when primers annealing within this segment were used, sequencing could easily extend through the borders, confirming that the phenomenon was due to secondary structure rather than abnormal sequence composition [26]. Similarly, PCR amplification across this region universally failed unless one primer annealed within the structured region, allowing polymerase to synthesize outward through the hairpin cluster [26].

High-Throughput Analysis of Polymerase Stalling

To comprehensively understand DNA synthesis through structured regions, researchers developed a high-throughput primer extension assay that monitored the kinetics of DNA synthesis through 20,000 sequences comprising all short tandem repeat (STR) permutations in different lengths [25]. This approach combined experimental measurements with population-scale genomic data to demonstrate that the response of a model replicative DNA polymerase (T7 DNA polymerase) to variously structured DNA is sufficient to predict the complex genomic behavior of STRs, including their abundance and mutational constraints [25].

The study revealed that DNA polymerase stalling at DNA structures induces error-prone DNA synthesis, which in turn constrains STR expansion [25]. This supports a model where STR length in eukaryotic genomes results from a balance between expansion due to polymerase slippage at repeated DNA sequences and point mutations caused by error-prone DNA synthesis at DNA structures [25]. The data further explained why structured STRs are generally more stable over evolutionary time, as their expansion is limited by increased point mutation rates at structural boundaries.

Conservation and Functional Significance

The polymerase-resistant region upstream of Foxd3 demonstrates another remarkable feature—significant evolutionary conservation across vertebrate species [26]. Nucleotide BLAST analysis revealed conservation with human, monkey, zebrafish, chicken, and frog genomes [26]. This high degree of conservation suggests possible functional significance, potentially in gene regulation, and indicates that these problematic structural elements are maintained by natural selection despite their technical challenges for amplification.

Overcoming Structural Barriers: Optimized Methodologies

Polymerase Selection and Engineering

The choice of DNA polymerase is critical for amplifying structured templates. Standard Taq polymerase often struggles with GC-rich secondary structures, but several specialized enzymes show superior performance:

- OneTaq DNA Polymerase: Developed with both standard and GC buffers, this enzyme provides high yield and specificity for difficult amplicons and can amplify templates with up to 80% GC content when supplemented with the OneTaq High GC Enhancer [24] [23].

- Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase: With more than 280 times the fidelity of Taq, Q5 is ideal for long or difficult amplicons, including GC-rich DNA. Its GC enhancer enables robust performance up to 80% GC content [24] [23].

- Engineered polymerases with enhanced processivity: Some modern polymerases are engineered with a strong DNA-binding domain from another protein, enhancing their ability to unwind structured templates without compromising polymerase activity [29].

- Hyperthermostable polymerases: Enzymes from hyperthermophilic organisms like Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu) exhibit greater thermostability, with Pfu having approximately 20 times the stability of Taq at 95°C, enabling them to better withstand the elevated denaturation temperatures needed for GC-rich templates [29].

Table 2: Optimization Strategies for Amplifying Structured DNA Templates

| Parameter | Standard Conditions | Optimized for GC-Rich Templates | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymerase Type | Standard Taq | Specialized polymerases (OneTaq, Q5) with GC enhancers | Improved processivity through secondary structures |

| Denaturation Temperature | 92-95°C | Up to 98°C (first few cycles) | Enhanced separation of stable duplexes |

| Mg²⁺ Concentration | 1.5-2.0 mM | Gradient optimization (1.0-4.0 mM) | Cofactor optimization for enzyme activity |

| Additives | None | DMSO, betaine, glycerol, formamide | Destabilization of secondary structures |

| Cycle Modifications | Standard ramp rates | Slow-down PCR with modified nucleotides | Reduced structure formation with analogs |

| Template Modification | Direct amplification | Restriction digestion and subcloning | Reduction of GC content in amplified fragments |

PCR Additives and Buffer Optimization

Chemical additives can significantly improve amplification of structured templates by destabilizing secondary structures:

- Structure-destabilizing agents: DMSO, glycerol, and betaine work by reducing the formation of secondary structures that inhibit polymerase progression [24] [14]. Betaine is particularly effective as it reduces the base-stacking energy penalty for DNA melting, effectively lowering the melting temperature of GC-rich regions [30].

- Stringency enhancers: Formamide and tetramethyl ammonium chloride increase primer annealing stringency, which increases specificity and reduces non-specific priming [24].

- Nucleotide analogs: 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine is a dGTP analog that improves PCR yield of GC-rich regions by preventing alternative (Hoogsteen) base pairing while maintaining standard Watson-Crick base pairing [27] [14]. This destabilizes secondary structures without compromising accurate replication.

Commercial GC enhancers often contain proprietary mixtures of these additives in optimized ratios, providing a convenient solution without the need for laborious individual testing [24] [23].

Thermal Cycling and Reaction Condition Modifications

Adjusting thermal cycling parameters can significantly improve amplification of structured templates:

- Elevated denaturation temperature: Increasing the denaturation temperature to 98°C for the first few cycles helps melt stable secondary structures, though this should be used cautiously as it can accelerate polymerase denaturation [14].

- Temperature gradients: Empirical testing of annealing temperatures using temperature gradients helps identify optimal conditions that balance specificity and yield [24].

- Slow-down PCR: This method uses a standardized cycling protocol with varying temperatures, lowered ramp rates, additional cycles, and the inclusion of 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine [14].

- Modified magnesium concentration: Magnesium is a crucial cofactor for polymerase activity and primer binding. Testing MgCl₂ concentrations in 0.5 mM increments between 1.0 and 4.0 mM can identify the optimal concentration that maximizes yield while minimizing non-specific amplification [24] [23].

Template and Primer Design Strategies

When standard optimization fails, alternative approaches focus on modifying the template itself:

- Restriction digestion and subcloning: Cutting the problematic region with restriction enzymes and subcloning smaller fragments (ideally up to 200 bp) reduces the local GC content and minimizes structure formation [27] [26].

- Internal priming: Using one primer that anneals within the structured region can allow polymerase to synthesize outward through the hairpin, as polymerases seem better able to extend through structures than to initiate replication through them [26].

- Bidirectional sequencing: When sequencing through structured regions, using both forward and reverse primers that anneal within the structured region can help assemble a complete sequence [27].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Secondary Structure Challenges

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | Amplification through stable structures | OneTaq DNA Polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase |

| GC Enhancers | Proprietary additive mixtures | OneTaq High GC Enhancer, Q5 High GC Enhancer |

| Structure-Destabilizing Additives | Reduce secondary structure formation | DMSO, betaine, glycerol |

| Stringency Enhancers | Improve primer specificity | Formamide, tetramethyl ammonium chloride |

| Nucleotide Analogs | Destabilize non-B-form DNA | 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine |

| Hot-Start Enzymes | Prevent non-specific amplification | Antibody-mediated hot-start polymerases |

| Prediction Software | Identify potential structured regions | RNAfold, UNAfold, NEB Tm Calculator |

| Direct PCR Kits | Amplification from inhibitor-rich samples | Q5 Blood Direct 2X Master Mix |

Visualizing Experimental Approaches and Outcomes

The following workflow diagram illustrates a high-throughput methodology for analyzing polymerase stalling at structured DNA sequences, synthesizing the experimental approach from the research cited herein:

High-Throughput Analysis of Polymerase Stalling

The amplification of GC-rich templates remains challenging due to the fundamental biophysical properties of DNA that favor stable secondary structure formation. However, through understanding the mechanisms of polymerase stalling and implementing systematic optimization strategies, researchers can successfully overcome these barriers. The evidence indicates that DNA secondary structures—particularly hairpins, G-quadruplexes, and i-motifs—physically impede polymerase progression, leading to incomplete amplification and sequencing failures.

Future directions in this field include the development of increasingly processive polymerases through protein engineering, the refinement of predictive algorithms to identify problematic sequences during primer design, and the application of deep learning approaches to forecast sequence-specific amplification efficiency [28]. The demonstrated conservation of structured regions in genomes suggests they may play important regulatory roles worthy of further investigation [26]. As these technical challenges are addressed, our ability to study GC-rich genomic regions will continue to improve, advancing both basic research and applied diagnostic applications.

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet the amplification of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) templates with high guanine-cytosine (GC) content remains a significant technical challenge. GC-rich sequences, typically defined as those where 60% or more of the bases are guanine or cytosine, present formidable obstacles to efficient amplification due to their inherent biochemical properties [31] [14]. These difficulties manifest primarily during two critical stages of the PCR cycle: the complete denaturation of double-stranded DNA into single strands, and the specific annealing of primers to their target sequences. When either process fails, the consequences include complete amplification failure, reduced product yield, or the generation of non-specific products [32] [2].

The significance of overcoming these challenges extends beyond technical troubleshooting. Approximately 3% of the human genome consists of GC-rich regions, and these areas are disproportionately represented in the promoter regions of housekeeping genes, tumor suppressor genes, and other critical regulatory elements [31] [2]. Consequently, researchers investigating gene regulation, developing diagnostic assays, or working with organisms such as Mycobacterium bovis (with a genome >60% GC content) frequently encounter these amplification hurdles [10]. This technical guide examines the molecular basis of incomplete denaturation and primer annealing failure in GC-rich templates, provides experimental strategies for overcoming these challenges, and presents quantitative data to inform protocol optimization.

The Biochemical Basis of GC-Rich Amplification Difficulties

Enhanced Thermal Stability and Secondary Structure Formation

The primary challenge in amplifying GC-rich templates stems from the superior thermodynamic stability of GC base pairs compared to adenine-thymine (AT) pairs. Each GC base pair forms three hydrogen bonds, while AT pairs form only two, resulting in a significantly higher melting temperature ((T_m)) for GC-rich DNA [31]. This increased stability means that standard denaturation temperatures (typically 94-95°C) may be insufficient to completely separate double-stranded GC-rich regions, leaving portions of the template in a partially duplexed state [14]. This incomplete denaturation has immediate consequences: it prevents primers from accessing their complete binding sites and provides a physical barrier to polymerase procession.

Beyond simple duplex stability, GC-rich sequences readily form stable secondary structures that impede amplification. These include hairpin loops and intramolecular structures that occur when single-stranded DNA regions fold back upon themselves through self-complementarity [31] [14]. These structures are exceptionally stable due to their high GC content and can accumulate during PCR cycling. When primers attempt to bind to regions involved in these secondary structures, or when DNA polymerase encounters them during extension, the process stalls, leading to truncated amplification products or complete reaction failure [31]. The stability of these secondary structures is maintained by base stacking interactions, which provide even greater stabilization than hydrogen bonding alone [14].

Primer-Related Challenges in GC-Rich Environments

The challenges of GC-rich amplification extend to primer behavior and specificity. Primers designed for GC-rich targets often exhibit problematic characteristics that complicate annealing. These primers can form self-structures (hairpins) or interact with each other to create primer-dimers, both of which reduce the concentration of available primers for target binding [32] [14]. Additionally, the primers themselves may have high GC content, particularly at their 3' ends, which can promote mispriming at non-target sites that feature partial complementarity [14].

The annealing step becomes particularly problematic because the optimal conditions for GC-rich templates exist within a narrow window. Theoretical models and experimental confirmation have demonstrated that annealing efficiency (η) for GC-rich templates is highly dependent on both temperature ((TA)) and annealing time ((tA)), with optimal conditions confined to a much narrower range compared to templates with normal GC content [2] [33]. When annealing times exceed this optimal window (typically >10 seconds for highly GC-rich templates), the result is often smeared amplification products with multiple non-specific bands, indicating competitive binding at alternative sites [2]. This phenomenon occurs because longer annealing times increase the probability of primers binding to incorrect, partially complementary sites on the template DNA.

Quantitative Analysis of GC-Rich Amplification Parameters

Optimal Annealing Conditions for GC-Rich Templates

Research has quantitatively established that GC-rich templates require significantly different cycling parameters compared to standard templates. A fundamental study examining the amplification of the human ARX gene (78.72% GC content) demonstrated that annealing times between 3-6 seconds at appropriate temperatures yielded specific amplification, while longer annealing times produced increasing smear and non-specific products [2]. The table below summarizes the optimal versus suboptimal conditions based on experimental data:

Table 1: Optimal Annealing Conditions for GC-Rich vs. Normal GC Templates

| Parameter | GC-Rich Template (78.72% GC) | Normal GC Template (52.99% GC) | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annealing Time | 3-6 seconds | 10-30 seconds | Longer times (>10s) cause smearing in GC-rich templates [2] |

| Annealing Temperature Range | Narrow (2-4°C optimal range) | Broad (5-10°C workable range) | GC-rich templates show specific amplification only in narrow temperature windows [2] |

| Annealing Time Sensitivity | High | Low | GC-rich templates exhibit rapid degradation of specificity with extended times [2] [33] |

| Effect of Over-long Annealing | Smearing, multiple bands, reduced yield | Minimal impact on specificity | Competitive binding at alternative sites occurs in GC-rich templates [2] |

Effects of Reaction Components on Amplification Success

The concentration of various reaction components requires careful optimization for GC-rich templates. Magnesium ion (Mg²⁺) concentration, in particular, plays a critical role as it serves as a essential cofactor for DNA polymerase activity and facilitates primer binding by reducing electrostatic repulsion between negatively charged DNA strands [31]. The table below outlines key reaction components and their optimization ranges for GC-rich amplification:

Table 2: Optimization of Reaction Components for GC-Rich Templates

| Component | Standard Concentration | GC-Rich Optimization | Function and Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg²⁺ | 1.5-2.0 mM | 1.0-4.0 mM (test in 0.5 mM increments) | Critical for polymerase activity; excess causes non-specific binding [31] |

| Polymerase | Standard Taq | Specialized enzymes (OneTaq, Q5, KOD) | GC-rich templates require polymerases that can handle secondary structures [31] [2] |

| dNTPs | 200 μM each | 200 μM each | Balanced dNTP pools are essential; avoid excess [32] |

| Additives | None | DMSO (1-10%), Betaine (0.5-2.5 M), Formamide (1.25-10%) | Reduce secondary structure formation; increase primer stringency [32] [31] [2] |

| Template Amount | 10⁴-10⁷ molecules | 10⁴-10⁷ molecules | Excess template can increase non-specific amplification [32] |

Experimental Strategies and Protocols for GC-Rich Templates

Comprehensive Protocol for GC-Rich Amplification

Based on experimental data from multiple sources, the following protocol provides a robust starting point for amplifying GC-rich templates:

Reaction Setup:

- Template Preparation: Use 1-1000 ng of genomic DNA or 1-10 μL of cDNA in a 50 μL reaction [32]. For particularly challenging templates, consider NaOH denaturation prior to PCR setup [2].

- Master Mix Composition:

- 5 μL of 10X PCR buffer (preferably GC-enhanced formulation)

- 1 μL of 10 mM dNTPs (200 μM final concentration)

- 1-8 μL of 25 mM MgCl₂ (1.0-4.0 mM final concentration; optimize for each template)

- 1 μL each of forward and reverse primer (20 μM stock, 20-50 pmol final)

- 0.5-2.5 units of DNA polymerase (select specialized enzyme for GC-rich templates)

- 1-10% DMSO or 0.5-2.5 M betaine (test additives systematically)

- Sterile distilled water to 50 μL final volume [32] [31]

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 94-98°C for 2-5 minutes (longer for complex genomic DNA)

- Amplification Cycles (35-40 cycles):

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes [32] [2] [10]

Critical Notes: For the human ARX gene (78.72% GC), optimal results were achieved with a 3-second annealing time at 60°C [2]. Always include positive and negative controls. When testing new conditions, employ gradient PCR for annealing temperature optimization and magnesium titration.

Specialized Methodologies for Challenging Templates

For exceptionally long GC-rich targets (>1 kb), modified approaches may be necessary:

- Two-Step PCR Protocol: Combine annealing and extension into a single step at 68-72°C, which can improve amplification efficiency for complex templates [10].

- Slow-Down PCR: This method incorporates 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine (a dGTP analog) and uses standardized cycling with lowered ramp rates and additional cycles [14].

- Touchdown PCR: Begin with higher annealing temperatures in initial cycles, gradually decreasing in subsequent cycles to increase specificity while maintaining yield.

- Additive Combinations: Systematic testing of betaine (1.0 M) with DMSO (6-8%) or DMSO (5%) with betaine (1.2-1.8 M) has proven effective for particularly challenging GC-rich regions [34].

Successful amplification of GC-rich templates often requires specialized reagents and additives. The following table catalogues key solutions mentioned in the research literature:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for GC-Rich PCR Amplification

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | OneTaq DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0480), Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB #M0491), KOD Hot-Start Polymerase, AccuPrime GC-Rich DNA Polymerase | Engineered to withstand higher denaturation temperatures and overcome secondary structures [31] [2] [14] |

| GC Enhancers | OneTaq High GC Enhancer, Q5 High GC Enhancer | Proprietary formulations containing additives that inhibit secondary structure formation and increase primer stringency [31] |

| Chemical Additives | DMSO (1-10%), Betaine (0.5-2.5 M), Formamide (1.25-10%), 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine | Reduce secondary structures (DMSO, glycerol, betaine) or increase primer annealing stringency (formamide) [31] [2] |

| Optimization Kits | PCR Optimizer Kit (Cat. No. K122001) | Systematic approach to testing different buffer conditions and additives [34] |

| Universal Annealing Systems | Platinum DNA Polymerases with universal annealing buffer | Allows consistent 60°C annealing temperature for primers with different Tms through isostabilizing components [35] |

The amplification of GC-rich templates presents distinct challenges that stem from the fundamental biochemistry of DNA stability and hybridization. Incomplete denaturation and primer annealing failure represent two interconnected obstacles that collectively undermine amplification efficiency and specificity. Through a comprehensive understanding of the thermodynamic principles involved and systematic application of optimized protocols, researchers can overcome these barriers.

The experimental evidence confirms that successful amplification of GC-rich regions requires precisely controlled annealing times, specialized reaction components, and sometimes modified thermal cycling parameters. The quantitative data presented herein provides a foundation for evidence-based protocol optimization, moving beyond trial-and-error approaches to a more principled methodology. As research continues to focus on regulatory genomic regions and GC-rich pathogens, these optimization strategies will remain essential tools in the molecular biologist's arsenal.

Advanced Strategies and Reagent Selection for GC-Rich Amplification

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification of GC-rich DNA sequences (typically >60% GC content) presents a significant challenge in molecular biology, often leading to failed or inefficient reactions. The primary difficulty stems from the robust secondary structures formed by GC-rich regions. The triple hydrogen bonding between guanine (G) and cytosine (C) results in a higher melting temperature (Tm) for these sequences compared to adenosine (A) and thymine (T) rich regions. This inherent stability promotes the formation of rigid secondary structures, such as hairpins and G-quadruplexes, which impede the progression of the DNA polymerase enzyme [36]. Consequently, these structures cause premature dissociation of the polymerase from the template, resulting in short, incomplete products, or a complete failure of amplification. This technical hurdle is a critical consideration in a broad range of applications, from cloning gene promoters to analyzing methylation patterns via bisulfite-treated DNA, making the selection of an appropriate DNA polymerase a cornerstone of successful experimental design.

Critical DNA Polymerase Characteristics for PCR

The performance of a DNA polymerase in challenging amplifications is governed by four key properties: thermostability, processivity, fidelity, and specificity. Understanding these traits is essential for informed enzyme selection [29].

- Thermostability: This refers to the enzyme's ability to retain its structure and function at the high temperatures required for PCR, particularly during the denaturation step (often >90°C). While standard Taq polymerase is sufficiently stable for basic protocols, its half-life decreases significantly above 90°C. For GC-rich templates that require prolonged or higher-temperature denaturation, hyperthermostable enzymes derived from archaea like Pyrococcus furiosus (e.g., Pfu) are preferable due to their enhanced stability [29].

- Processivity: Defined as the number of nucleotides incorporated per enzyme-binding event, processivity is a crucial factor for amplifying long templates or those with complex secondary structures. A highly processive polymerase remains bound to the template for longer, effectively "plowing through" stable GC-rich hairpins. Early proofreading enzymes often had low processivity, but modern engineered versions frequently include DNA-binding domains to enhance this characteristic, enabling successful amplification of targets from suboptimal samples [29].

- Fidelity: Fidelity is the accuracy of DNA replication. It is critically important in applications like cloning, sequencing, and mutagenesis, where sequence errors can compromise downstream results. Fidelity is quantitatively expressed as the error rate (e.g., errors per base per duplication), and high-fidelity polymerases possess 3'→5' exonuclease (proofreading) activity that corrects misincorporated nucleotides. The fidelity of different enzymes is often reported relative to Taq polymerase [29] [37].

- Specificity: This ensures that only the intended target is amplified. Nonspecific amplification, such as primer-dimers or off-target products, is a common issue. A primary method to enhance specificity is the use of "hot-start" polymerases, which are inactive at room temperature. These enzymes are inhibited by antibodies, chemical modifications, or aptamers during reaction setup and are only activated by a high-temperature initial denaturation step, preventing spurious amplification before thermal cycling begins [29].

Quantitative Comparison of DNA Polymerases

Selecting the right polymerase requires a comparative understanding of their technical specifications. The tables below summarize key performance metrics for a range of commercially available enzymes.

Table 1: DNA Polymerase Fidelity and Error Rates

| Polymerase | 3'→5' Exonuclease (Proofreading) | Fidelity (Relative to Taq) | Reported Error Rate | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taq | No | 1x | 1.1x10⁻⁴ to 2.0x10⁻⁵ [37] [38] | Routine PCR, genotyping |

| OneTaq | Yes | ~2x [38] | N/A | Routine PCR, colony PCR |

| Pfu | Yes | ~6-10x [29] [37] | ~1.3x10⁻⁶ [39] [37] | Cloning, high-fidelity PCR |

| KOD | Yes | ~10-50x [29] | N/A | High-fidelity PCR, GC-rich targets |

| Phusion | Yes | >50x [29] | 4.0x10⁻⁷ [37] [38] | High-fidelity PCR, cloning, complex templates |

| Q5 | Yes | 280x [38] | N/A | High-fidelity PCR, cloning, NGS library prep |

Table 2: Polymerase Solutions for Challenging Templates

| Polymerase | Key Feature | Recommended for GC-Rich Templates? | Recommended for Long-Range PCR? |

|---|---|---|---|

| PrimeSTAR GXL | High processivity, blended enzyme | Yes (Up to 90% GC) [36] | Yes (Up to 30 kb) [36] |

| LA Taq | Blended enzyme system | Yes (With GC Buffer) [36] | Yes |

| Phusion (GC Buffer) | Engineered for stability | Yes [38] | Yes |

| Pfu Ultra II | Engineered high-fidelity | Yes [39] | No |

| Tth | Reverse transcriptase activity | No | No |

A Decision Workflow for Polymerase Selection

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for selecting the most appropriate DNA polymerase based on template characteristics and experimental goals. This workflow synthesizes the key criteria of fidelity, template GC-content, and target length into a logical decision path.

Experimental Protocols for GC-Rich and High-Fidelity PCR

Optimized Protocol for Amplifying GC-Rich Templates

The following step-by-step protocol is designed to overcome the challenges of secondary structure in GC-rich sequences through the use of specialized enzymes and buffer additives.

- Polymerase and Buffer Selection: Use a polymerase blend or high-processivity enzyme specifically designed for GC-rich templates, such as PrimeSTAR GXL or LA Taq with a proprietary GC Buffer [36].

- Reaction Setup:

- Template: 1-100 ng genomic DNA or 0.1-10 ng plasmid DNA.

- Primers: 0.2-0.5 µM each, designed with a Tm close to 65°C. Ensure the 3' end is GC-stabilized [21].

- dNTPs: 200 µM each.

- Polymerase: 1.25 units of a high-performance enzyme.

- Additives: If not using a specialized GC buffer, include 1 M betaine or 3-5% DMSO to homogenize base-pair stability and lower the template's Tm [21].

- Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 2-5 minutes to fully denature complex secondary structures.

- Cycling (30-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10-30 seconds (use a higher temperature for more rapid denaturation).

- Annealing: 60-72°C for 15-30 seconds. Optimize this temperature using a gradient PCR cycler [21].

- Extension: 68°C for 30-60 seconds per kb.

- Final Extension: 68°C for 5-10 minutes.

Fidelity Measurement via Colony Screening Assay

To empirically determine the error rate of a DNA polymerase, a lacZ-based colony screening assay can be employed. This method relies on the loss of β-galactosidase function due to mutations introduced during PCR amplification of the lacZ gene [29] [37].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify a ~1.9 kb fragment of the lacZ gene using the test polymerase and a high-fidelity control polymerase (e.g., Pfu) under vendor-recommended conditions. Use a minimum of 30 cycles to accumulate detectable errors.

- Cloning: Purify the PCR products and clone them into a suitable plasmid vector using restriction enzyme digestion and ligation or a recombination-based cloning system (e.g., Gateway) [37].

- Transformation and Plating: Transform the ligated plasmids into an appropriate E. coli host strain and plate onto LB agar containing IPTG and X-gal.

- Screening and Analysis:

- Incubate plates at 37°C until blue and white colonies are visible.

- Blue Colonies: Contain a functional lacZ gene (no inactivating mutations).

- White Colonies: Contain a mutated, non-functional lacZ gene.

- Error Rate Calculation:

- Count the total number of colonies and the number of white colonies.

- The mutation frequency is calculated as (Number of white colonies) / (Total number of colonies).