BN-PAGE vs SDS-PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein Complex Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a detailed comparison of Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) and SDS-PAGE, two fundamental electrophoretic techniques for protein analysis.

BN-PAGE vs SDS-PAGE: A Comprehensive Guide to Protein Complex Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparison of Blue Native-PAGE (BN-PAGE) and SDS-PAGE, two fundamental electrophoretic techniques for protein analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of both methods, with BN-PAGE preserving native protein complexes for functional studies and SDS-PAGE providing denaturing separation for molecular weight determination. The scope extends to practical methodological protocols, troubleshooting for complex samples like membrane proteins, and validation through techniques such as in-gel activity assays and 2D electrophoresis. By synthesizing key operational and application differences, this guide aims to empower scientists in selecting the optimal technique for their specific research goals in structural biology and therapeutic development.

Core Principles: How BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE Work at the Molecular Level

In the field of protein analysis, electrophoresis stands as a fundamental technique for separating and characterizing complex protein mixtures. The choice between native and denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) represents a critical decision point that directly impacts experimental outcomes, particularly in the study of protein complexes. While SDS-PAGE has become the default method for determining molecular weight and assessing sample purity, Native PAGE (including Blue Native PAGE) offers unique advantages for preserving functional protein interactions. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these techniques, framed within the context of protein complex analysis, to empower researchers in selecting the optimal approach for their specific research objectives.

Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between these electrophoretic techniques lies in their treatment of protein structure during separation.

Denaturing SDS-PAGE employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) along with reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) or beta-mercaptoethanol to dismantle native protein structures. SDS binds uniformly to polypeptide chains, masking intrinsic charges and conferring a consistent negative charge-to-mass ratio, while reducing agents break disulfide bonds [1] [2]. Heating samples to 70-100°C completes the denaturation process, resulting in linearized proteins that separate based almost exclusively on molecular weight as they migrate through the gel matrix [3] [4].

In contrast, Native PAGE (including BN-PAGE) operates under non-denaturing conditions without SDS or reducing agents [1]. This technique preserves proteins in their folded, functional states, maintaining enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and bound cofactors [5] [3]. Separation depends on a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape, allowing researchers to study quaternary structures and native complexes [6] [4].

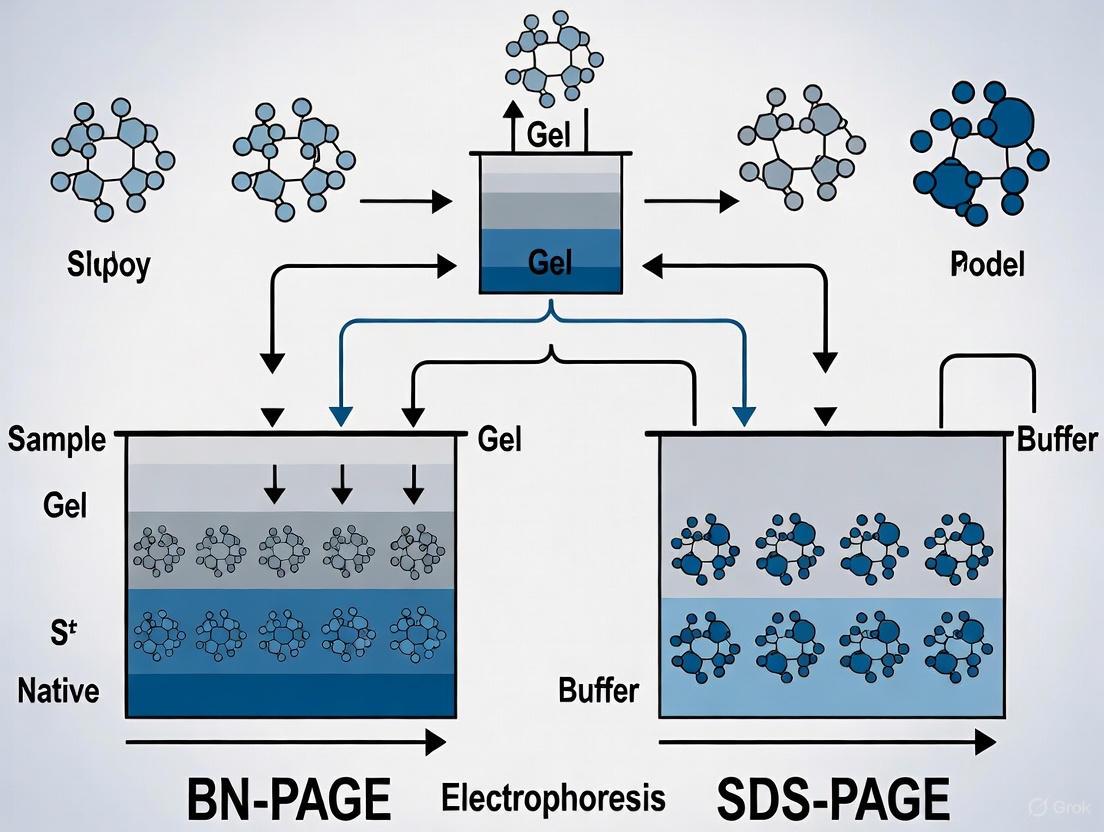

The workflow below illustrates the key procedural differences between these two fundamental methods:

Comparative Analysis: SDS-PAGE vs Native PAGE

The table below summarizes the key technical and application differences between these electrophoretic methods:

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Conditions | Denaturing [1] [7] | Non-denaturing [1] [7] |

| Key Reagents | SDS, DTT/β-mercaptoethanol [1] [2] | No denaturants; Coomassie in BN-PAGE [1] [8] |

| Sample Preparation | Heating required (70-100°C) [1] [4] | No heating [1] [2] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight only [3] [7] | Size, charge, and shape [3] [4] |

| Protein Structure | Denatured, linearized [5] [2] | Native conformation preserved [5] [3] |

| Protein Function | Lost after separation [1] | Retained after separation [1] [4] |

| Protein Recovery | Not recoverable functional [1] [7] | Recoverable functional [1] [7] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, western blotting, purity assessment [9] [3] [2] | Protein complexes, oligomeric state, enzymatic activity [9] [5] [3] |

| Typical Running Temperature | Room temperature [1] | 4°C [1] |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Recent research has quantified the performance differences between these techniques, particularly regarding functional preservation. A modified approach called Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) demonstrates the potential for balancing resolution with functional preservation.

Quantitative Comparison of Metal Retention and Enzyme Activity

The following table summarizes experimental data comparing standard SDS-PAGE, BN-PAGE, and NSDS-PAGE in preserving metalloprotein function:

| Method | Zinc Retention (%) | Enzyme Activity Retention (Model Enzymes) | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard SDS-PAGE | 26% [8] | 0/9 active [8] | High [5] [8] |

| BN-PAGE | Not specified | 9/9 active [8] | Lower than SDS-PAGE [8] |

| NSDS-PAGE | 98% [8] | 7/9 active [8] | Comparable to SDS-PAGE [8] |

This data demonstrates that NSDS-PAGE, which eliminates EDTA and reduces SDS concentration in running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375% while omitting the heating step, achieves near-complete metal retention while maintaining high resolution [8]. This approach represents a valuable hybrid technique for metalloprotein analysis.

Pre-fractionation Efficiency for Protein Complex Analysis

In affinity purification workflows for protein complex isolation, the choice of pre-fractionation method significantly impacts protein identification. When comparing SDS-PAGE and Strong Cation Exchange (SCX) chromatography for pre-fractionating nuclear protein complexes (Bmi-1 and GATA3), SCX consistently identified approximately 3-fold more proteins than SDS-PAGE [10]. This efficiency gap was especially pronounced for the Bmi-1 complex, where the target protein was expressed at low levels [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with 4X LDS sample buffer containing SDS and reducing agent. For standard SDS-PAGE, use 106 mM Tris HCl, 141 mM Tris Base, 0.51 mM EDTA, 2% LDS, 10% glycerol, pH 8.5 [8].

Denaturation: Heat samples at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to complete denaturation [8] [4].

Gel Preparation: Use precast or freshly cast polyacrylamide gels (typically 4-12% or 10% Bis-Tris gels) with SDS incorporated into the gel matrix [8] [4].

Electrophoresis: Load samples and molecular weight markers. Run at constant voltage (200V) for approximately 45 minutes using MOPS SDS running buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.7) at room temperature [8].

Detection: Visualize proteins using Coomassie, silver staining, or transfer to membrane for western blotting [10] [4].

Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with 4X BN-PAGE sample buffer (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2). Do not heat [8].

Gel Preparation: Use precast NativePAGE Novex 4-16% Bis-Tris gels or equivalent [8].

Electrophoresis: Load samples and native protein standards. Run at constant voltage (150V) for 90-95 minutes using cathode (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, 0.02% Coomassie G-250, pH 6.8) and anode (50 mM BisTris, 50 mM Tricine, pH 6.8) running buffers at room temperature [8].

Detection: Visualize proteins with compatible stains or process for activity assays [8].

Sample Preparation: Mix protein sample with 4X NSDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, 0.0185% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% Phenol Red, pH 8.5). Do not heat [8].

Gel Equilibration: Pre-run precast NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris gels at 200V for 30 minutes in double distilled H₂O to remove storage buffer and unpolymerized acrylamide [8].

Electrophoresis: Run at 200V for 30 minutes using NSDS-PAGE running buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7) [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines essential materials and their functions for these electrophoretic techniques:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins, confers negative charge [1] [4] | SDS-PAGE |

| DTT or β-mercaptoethanol | Reduces disulfide bonds [1] [2] | SDS-PAGE |

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts charge for electrophoresis, staining [8] | BN-PAGE |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms porous gel matrix for separation [4] | All PAGE |

| TEMED/Ammonium Persulfate | Catalyzes acrylamide polymerization [4] | All PAGE |

| Tris-based Buffers | Maintains pH during electrophoresis [8] [4] | All PAGE |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for gel loading [1] [8] | Sample preparation |

| MOPS/Tricine Buffers | Running buffer systems [8] | SDS-PAGE, NSDS-PAGE |

Application Workflows in Protein Complex Research

The diagram below illustrates typical research workflows for analyzing protein complexes using these complementary techniques:

Native and denaturing electrophoresis techniques offer complementary capabilities for protein complex analysis. SDS-PAGE remains the gold standard for determining subunit molecular weight and purity assessment, while Native PAGE (particularly BN-PAGE) excels at preserving functional protein interactions and quaternary structures. The emerging NSDS-PAGE method demonstrates that hybrid approaches can balance resolution with functional preservation, particularly for metalloprotein studies. Researchers should select methodologies based on their specific objectives: SDS-PAGE for analytical separation and molecular weight determination, Native PAGE for functional studies and complex analysis, and SCX chromatography for maximum protein identification in proteomic applications. Understanding these techniques' strengths and limitations enables more informed experimental design in protein complex research and drug development.

In the realm of protein research, particularly in the separation and analysis of protein complexes via techniques like Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and SDS-PAGE, the choice of detergent is far from a mere technicality. It is a critical decision that dictates the success of an experiment. Detergents, or surfactants, are amphiphilic molecules essential for solubilizing membranes and proteins, but their chemical nature can either preserve or obliterate the delicate structures and functions of biological molecules. Non-ionic detergents, characterized by their uncharged hydrophilic heads, are celebrated for their mild, protein-friendly properties. In contrast, ionic detergents, which carry a distinct electrical charge, are powerful agents for denaturation and complete disruption. This guide provides an objective comparison of these detergent classes, framing their performance within the context of modern protein complex analysis and supporting conclusions with experimental data.

Fundamental Detergent Chemistry and Properties

At the molecular level, the distinction between ionic and non-ionic surfactants is defined by the nature of their hydrophilic (water-attracting) head groups.

- Ionic Surfactants possess a charged hydrophilic head group. When dissolved in water, they dissociate into ions, leading to electrostatic interactions with the solution and other molecules [11]. This class is further divided:

- Anionic Surfactants (e.g., Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate - SDS) have a negatively charged head group [11] [8]. They are renowned for their strong cleaning and foaming power but can be irritating to skin and eyes [11] [12].

- Cationic Surfactants (e.g., Dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide - DTAB) have a positively charged head group [11] [13]. They are often used for their antimicrobial properties and are found in products like fabric softeners and hair conditioners [11].

- Non-Ionic Surfactants, such as Triton X-100 and n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM), feature an uncharged hydrophilic head group [11] [14]. They do not dissociate into ions in water, which makes them generally milder, less irritating, and less disruptive to protein structure and function [11] [15].

The table below summarizes the core differences that arise from these distinct chemical structures.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Ionic and Non-Ionic Detergents

| Property | Ionic Detergents | Non-Ionic Detergents |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | Charged head group (positive or negative) [11] | Uncharged head group [11] |

| Protein Interaction | Strong, often denatures proteins [8] [15] | Mild, can preserve native structure/function [14] [8] |

| Foam Production | High [11] | Low [15] |

| Tolerance (Skin/Eyes) | More irritating [11] | Milder, less irritating [11] |

| Hard Water Tolerance | Low (precipitate with ions) [16] | High (effective in hard water) [16] [15] |

| Compatibility | Can interact with charged ingredients [11] | Highly compatible with various ingredients [11] |

A simple method to distinguish between the two classes in the lab is a conductivity test. Since ionic surfactants dissociate into ions, they will conduct electricity in solution, whereas non-ionic surfactants will not significantly alter the solution's conductivity [11].

Detergent Applications in Protein Electrophoresis

The fundamental properties of detergents dictate their roles in key electrophoretic techniques for protein analysis. The choice between BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE is fundamentally a choice between preserving or destroying native protein structures.

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE): Preserving Complexes with Non-Ionic Agents

The primary goal of BN-PAGE is to separate intact protein complexes in their native, enzymatically active state [14] [8]. To achieve this, non-ionic detergents are the reagents of choice.

- Experimental Protocol for BN-PAGE: A standard protocol involves solubilizing membrane protein complexes with a non-denaturing detergent. The solubilized samples are then mixed with Coomassie Blue G dye, which binds to proteins in a non-stoichiometric way, imparting a negative charge shift to enable migration toward the anode while preserving the complex's structure [14]. Typical detergent concentrations range from 0.5% to 2% final concentration, or a detergent-to-protein ratio from 1:1 to 10:1 [14].

- Key Reagents: The most frequently used non-ionic detergents for BN-PAGE include digitonin, n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside, and Triton X-100 [14]. Their "mildness" refers to their ability to solubilize membranes without disrupting the critical lipid-protein and protein-protein interactions that hold complexes together [14].

SDS-PAGE: Denaturing Separation with Ionic Agents

In stark contrast, SDS-PAGE aims to separate individual protein subunits based almost exclusively on their molecular weight. This requires the complete denaturation of proteins and the disruption of all non-covalent interactions.

- The Role of Ionic SDS: The anionic detergent Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) is the cornerstone of this method. Proteins are denatured by heating in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent. SDS binds uniformly to the polypeptide backbone, with a constant mass ratio, which masks the protein's intrinsic charge and imparts a uniform negative charge [8] [17]. This results in all proteins having a similar charge-to-mass ratio, allowing separation by size as they migrate through a polyacrylamide gel [17].

- Limitation and a Hybrid Approach: A significant limitation of standard SDS-PAGE is the deliberate destruction of functional properties, including enzymatic activity and the presence of non-covalently bound cofactors like metal ions [8]. To address this, a modified method called native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) has been developed. This protocol omits the heating step and reduces the SDS concentration in the running buffer (e.g., to 0.0375%), which allows for high-resolution separation while retaining Zn²⁺ in metalloproteins and preserving the activity of many enzymes [8].

Table 2: Detergent Use in Key Electrophoretic Methods

| Electrophoresis Method | Primary Detergent Class | Key Detergents | Objective | Impact on Protein Complexes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BN-PAGE | Non-Ionic [14] | Dodecyl maltoside, Digitonin, Triton X-100 [14] | Separate native complexes | Preserves intact structure and function |

| SDS-PAGE | Ionic (Anionic) [8] | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [8] | Separate denatured subunits | Disassembles complexes into subunits |

| NSDS-PAGE | Ionic (Anionic, reduced) [8] | SDS (at low concentration) [8] | High-resolution native separation | Preserves some metal ions & activity |

Comparative Experimental Data and Emerging Trends

Recent research provides quantitative data on how detergent selection directly impacts experimental outcomes, such as the number of proteins identified and the success of novel reconstitution techniques.

Impact on Proteome Analysis and Identification

A 2025 study investigating detergent screens for bottom-up proteomics on Escherichia coli highlights a clear benefit of using a diverse detergent portfolio. The research employed ionic detergents (SDS and cationic DTAB), a non-ionic detergent (dendritic triglycerol detergent), and related hybrid detergents [13]. The findings were striking:

- Combining proteomics datasets from the different detergents increased the number of unique protein identities (IDs) observed from 1,604 to 2,169 [13].

- This demonstrates that the solubilizing bias of each detergent is unique and that cationic detergents and hybrid detergents, often underrepresented in proteomics, can significantly enhance the observable proteome when used alongside traditional anionic and non-ionic agents [13].

The Rise of Detergent-Free and Hybrid Technologies

The limitations of detergents in preserving the precise native lipid environment have spurred the development of advanced technologies.

- Detergent-Free Reconstitution: A groundbreaking 2025 study published in Nature Communications introduced "DeFrND," a method using engineered membrane-scaffolding peptides (DeFrMSPs) to directly extract membrane proteins from native cell membranes into nanodiscs, completely bypassing the need for detergents [18]. This approach was critical for studying detergent-sensitive complexes like the MalFGK2 transporter, which, when extracted with peptides, maintained its functional coupling, unlike when solubilized with detergents or amphipathic polymers [18].

- Hybrid Detergents: Research is also exploring the potential of ionic/nonionic hybrid detergents, which covalently combine headgroups from both classes. Data suggests their solubilizing properties are not a simple average of the parent detergents and can contribute to increased proteome coverage, as noted above [13].

Table 3: Experimental Performance Data of Detergent Classes

| Experimental Context | Non-Ionic Detergent Performance | Ionic Detergent Performance | Hybrid/Novel Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteome Coverage (E. coli) | Contributes unique protein IDs [13] | SDS provides high baseline IDs; cationic DTAB adds unique IDs [13] | Combining all data increases unique protein IDs from 1604 to 2169 [13] |

| Membrane Protein Complex Study | Standard for preserving activity in BN-PAGE [14] | Often denatures and inactivates complexes [8] | Detergent-free native nanodiscs (DeFrND) preserve functional coupling better than polymers or detergents [18] |

| Protein Solubilization Bias | Specific bias for certain protein classes [13] [14] | Strong, complementary bias for different protein classes [13] | Hybrid detergents exhibit unique solubilization profiles not seen in canonical detergents [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Detergent-Based Research

This table catalogs key reagents and their functions for researchers designing experiments in protein complex analysis.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Key Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Strong Ionic Detergent | Denatures proteins, binds uniformly to impart charge for SDS-PAGE. | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [8] |

| Mild Non-Ionic Detergent | Solubilizes membranes and proteins while preserving native complexes for BN-PAGE. | n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM), Triton X-100, Digitonin [14] |

| Cationic Detergent | Offers complementary solubilization bias in proteomic screens. | Dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) [13] |

| Hybrid Detergent | Covalently fused ionic/nonionic headgroups for unique solubilization properties. | Ionic/Nonionic hybrid structures [13] |

| Membrane Scaffold Peptide | Enables detergent-free extraction of membrane proteins into native nanodiscs. | Engineered Apolipoprotein-A1 mimetic peptides (DeFrMSPs) [18] |

| Coomassie Dye (G-250) | Imparts charge shift for electrophoretic migration in BN-PAGE without full denaturation. | Coomassie Blue G [14] |

The dichotomy between mild non-ionic and strong ionic detergents is a foundational principle in protein science. Non-ionic detergents are indispensable for the isolation and analysis of intact, functional protein complexes using techniques like BN-PAGE. Conversely, ionic detergents like SDS are powerful tools for deconstructing proteomes into their constituent subunits for precise molecular weight determination via SDS-PAGE. The emerging experimental data unequivocally shows that no single detergent is universally superior. The most advanced proteomic and structural biology research now leverages the complementary strengths of both classes, and even looks beyond them to hybrid and fully detergent-free systems. The optimal experimental outcome hinges on a rational selection of the solubilizing agent, aligned with the fundamental question being asked about the protein or complex under investigation.

In the field of protein analysis, electrophoresis is a foundational technique for separating and characterizing proteins. Two principal methods, Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), represent fundamentally different approaches defined by how they manage protein state and charge. SDS-PAGE employs denaturing conditions to unfold proteins and impart a uniform negative charge, separating polypeptides primarily by molecular weight. In contrast, BN-PAGE operates under non-denaturing conditions to preserve native protein conformations, multi-subunit complexes, and biological functions, separating complexes based on both size and intrinsic charge [1] [19]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on their mechanistic principles, experimental outcomes, and applications in drug development and basic research.

Core Principles: A Tale of Two Techniques

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight

SDS-PAGE is a denaturing electrophoresis technique that separates individual polypeptide chains based almost exclusively on their molecular weight [1]. The anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) binds extensively to hydrophobic regions of proteins, disrupting their tertiary structure and unfolding them. This SDS coating confers a uniform negative charge density, meaning all proteins experience similar charge-to-mass ratios. Consequently, when an electric field is applied, separation occurs as proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix at rates inversely proportional to their molecular size, with smaller proteins moving faster [1] [8]. The reducing agents present in the buffer, such as DTT or β-mercaptoethanol, break disulfide bonds, ensuring complete denaturation into constituent subunits [20].

BN-PAGE: Separation of Native Complexes by Size and Charge

BN-PAGE is a non-denaturing technique designed to separate intact protein complexes in their functional, folded state [21] [22] [19]. Instead of SDS, the anionic dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 is used. This dye binds non-covalently to the surface of protein complexes, imparting a negative charge without causing significant dissociation or denaturation [22] [20] [19]. The resulting separation in the polyacrylamide gel depends on both the native molecular mass and the shape of the protein complex, as well as the number of dye molecules bound, which relates to the complex's surface charge [1] [19]. This preserves protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity, and the binding of non-covalently attached cofactors, including metal ions [8] [22].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental workflows and outcomes of these two techniques.

Quantitative Comparison: Technical Specifications and Outputs

Direct Technique Comparison

The choice between BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE has profound implications for the type of data obtained, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Fundamental differences between SDS-PAGE and BN-PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Molecular weight only [1] | Size, charge, and shape of complex [1] |

| Gel Conditions | Denaturing [1] | Non-denaturing [1] |

| SDS Presence | Present [1] | Absent [1] |

| Buffer Composition | Contains reducing agent (e.g., DTT, BME) [1] | No reducing agent [1] |

| Sample Preparation | Protein samples are heated [1] | Protein samples are not heated [1] |

| Protein Net Charge | Uniformly negative [1] | Can be positive or negative [1] |

| Typely | Room temperature [1] | 4°C [1] |

| Protein State | Denatured, unfolded [1] | Native conformation, folded [1] |

| Protein Function Post-Separation | Lost [1] [8] | Retained [1] [8] |

| Primary Application | Determine molecular weight, check purity/expression [1] | Study structure, subunit composition, and function [1] |

Experimental Data Comparison

The methodological differences lead to distinct functional outcomes, particularly regarding the preservation of enzymatic activity and metal cofactors, which is critical for functional studies.

Table 2: Experimental outcomes for protein activity and metal retention

| Experimental Parameter | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retention of Enzyme Activity | All nine model enzymes denatured and inactive [8] | All nine model enzymes active [8] | Seven of nine model enzymes active [8] |

| Zinc (Zn²⁺) Retention in Proteomic Samples | 26% retention [8] | High retention (implied) [8] | 98% retention [8] |

| Suitable for In-Gel Activity Assays | No [8] [22] | Yes [22] [23] | Yes (for most enzymes) [8] |

| Suitable for Western Blotting | Yes, standard method [8] | Yes, requires specific protocols [21] | Yes, requires optimization [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

SDS-PAGE Protocol

The following is a standard denaturing SDS-PAGE protocol based on established methods [8].

- Sample Preparation: Mix the protein sample with an SDS-based sample loading buffer (e.g., containing LDS) and a reducing agent like Dithiothreitol (DTT) [8].

- Denaturation: Heat the mixture at 70°C–95°C for 5–10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and reduction of disulfide bonds [1] [8].

- Gel Loading: Load the denatured samples into precast or hand-cast polyacrylamide gels. A pre-stained protein molecular weight standard should be loaded in at least one well.

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 150-200 V) at room temperature using an SDS-containing running buffer (e.g., MOPS-SDS buffer) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [8].

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: The gel can be stained (e.g., Coomassie, silver stain) for total protein visualization or used for Western blotting [24].

BN-PAGE Protocol

This BN-PAGE protocol is adapted from methodologies used for mitochondrial complexes [21] [23] and whole cell lysates [25] [26].

- Sample Preparation (Solubilization): Isolate the subcellular fraction (e.g., mitochondria) or whole cells. Solubilize the sample on ice using a mild, non-ionic detergent. Common choices include:

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized lysate at high speed (e.g., 16,000–72,000 x g) for 30 minutes to remove insoluble debris. The supernatant contains the solubilized protein complexes [21].

- Dye Addition: Add Coomassie Blue G-250 dye (e.g., as a 5% solution) to the supernatant to impart charge to the complexes [21].

- Gel Loading: Load the prepared sample into a native gradient gel (e.g., 4-16% or 6-13% acrylamide) without heating [21] [23].

- Electrophoresis: Run the gel under native conditions at 4°C [1]. The cathode buffer (pH ~7.0) contains Coomassie dye, while the anode buffer lacks it. Start electrophoresis at a low voltage (e.g., 150 V) and potentially increase after the dye front has migrated partially into the gel [23].

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- First Dimension Analysis: Complexes can be visualized by Coomassie staining, immunoblotting with specific antibodies, or in-gel activity assays [22] [23].

- Second Dimension (2D) Analysis: For subunit analysis, a lane from the BN-PAGE gel can be excised, soaked in SDS buffer, and placed on an SDS-PAGE gel. This 2D BN/SDS-PAGE separates complexes in the first dimension and their constituent subunits in the second [25] [23] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE relies on specific reagents, each with a critical function.

Table 3: Key reagents for protein electrophoresis

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge. | SDS-PAGE [1] |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agent that breaks disulfide bonds. | SDS-PAGE [1] [20] |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge to protein surfaces under native conditions. | BN-PAGE [21] [22] [19] |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild non-ionic detergent for solubilizing membrane protein complexes. | BN-PAGE [21] [23] [19] |

| Digitonin | Mild detergent used to preserve labile supercomplexes. | BN-PAGE [19] |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt that aids protein solubilization and complex stability. | BN-PAGE [21] [19] |

| Bis-Tris | A buffering agent used to maintain stable pH in native conditions. | BN-PAGE [21] [23] |

Application in Research and Drug Development

The complementary nature of BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE makes them invaluable across research and development.

Studying Protein Complex Dynamics and Assembly: BN-PAGE is the preferred method for investigating the assembly pathways of multi-subunit complexes, identifying assembly intermediates, and detecting the presence of supercomplexes, such as those in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [22] [19]. This is crucial for understanding diseases arising from defective complex assembly.

Identifying Post-Translational Modifications within Complexes: The 2D BN/SDS-PAGE approach is powerful for identifying specific subunits within a complex that undergo post-translational modifications. For example, it has been used to pinpoint which subunits of mitochondrial complex I are modified by the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) in diabetic models [23].

Functional Proteomics and Target Validation: In drug development, confirming a target protein's function and interaction partners is essential. BN-PAGE can validate that a drug candidate does not disrupt essential protein-protein interactions by demonstrating the intactness of complexes after treatment. Furthermore, it allows for in-gel activity assays to test how potential therapeutics affect enzymatic function of native complexes [22].

Analyzing Whole Cellular Lysates: Advancements have shown that with dialysis to remove interfering substances, BN-PAGE can be applied to whole cellular lysates, enabling the study of protein complexes like the proteasome and tumor suppressors (e.g., p53) in a systems biology context [25] [26]. This provides a broader view of cellular interaction networks.

Historical Development and Key Innovators in Electrophoresis

The history of electrophoresis represents a relentless pursuit of analytical precision in biochemical research. From its initial discovery to its sophisticated contemporary applications, electrophoretic techniques have fundamentally transformed our capacity to resolve and characterize biological molecules. This evolution is particularly evident in the development of methods for protein analysis, where the critical dichotomy emerged between denaturing techniques that maximize resolution and native techniques that preserve functional integrity. This guide focuses on the pivotal development of Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and its comparison with traditional SDS-PAGE, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on experimental objectives. The trajectory from early moving-boundary methods to today's high-resolution native gel techniques illustrates how technological innovations have continuously expanded the horizons of proteomic research [27].

Historical Timeline and Key Innovators

The development of electrophoresis spans more than two centuries, marked by foundational discoveries and technological breakthroughs that have progressively enhanced its resolving power and applications.

Table 1: Key Historical Developments in Electrophoresis

| Year | Innovator(s) | Development | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1807 | Reuß & Strakhov | First observation of electrokinetic phenomena | Discovered clay particle migration in water under electric field [27] |

| 1930s | Arne Tiselius | Moving-boundary electrophoresis apparatus | Enabled analytical separation of chemical mixtures; Nobel Prize (1948) [27] |

| 1950s | Multiple groups | Zone electrophoresis | Introduced solid/gel matrices to separate compounds into discrete zones [27] |

| 1959 | Raymond & Weintraub | Acrylamide gel electrophoresis | Acrylamide introduced as superior supporting medium [27] |

| 1970s | Patrick O'Farrell | Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis | Combined IEF and SDS-PAGE for unprecedented resolution [28] |

| Early 1990s | Schägger & von Jagow | Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) | Enabled separation of native membrane protein complexes [29] [30] |

| 2000s | Multiple groups | Protocol optimizations | Standardized polyacrylamide gels for improved reproducibility [27] |

The earliest roots of electrophoresis trace back to 1807, when Russian professors Peter Ivanovich Strakhov and Ferdinand Frederic Reüss at Moscow University first observed that clay particles dispersed in water would migrate under the influence of a constant electric field—the first documented electrokinetic phenomenon [27]. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, scientists including Johann Wilhelm Hittorf, Walther Nernst, and Friedrich Kohlrausch developed the theoretical and experimental foundations for understanding ion movement in solutions, creating mathematical descriptions of electrochemistry and developing methods for creating moving boundaries of charged particles [27].

The transformative breakthrough for biochemical applications came from Arne Tiselius, who in the 1930s developed the moving-boundary electrophoresis apparatus with support from the Rockefeller Foundation [27]. His method, fully described in his seminal 1937 paper, enabled the analytical separation of chemical mixtures and earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1948 [27]. Despite its impact, the Tiselius method could not completely separate electrophoretically similar compounds, leading to the development of zone electrophoresis in the 1940s and 1950s, which used filter paper or gels as supporting media to separate compounds into discrete, stable bands [27].

The introduction of polyacrylamide gels in 1959 by Raymond and Weintraub represented a monumental advance, providing a superior matrix for protein separation [27]. This set the stage for the proteomics revolution when Patrick O'Farrell developed two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in the 1970s, combining isoelectric focusing (IEF) with SDS-PAGE to achieve unprecedented resolution of complex protein mixtures [28]. O'Farrell's innovation emerged from his graduate work at the University of Colorado, where he sought to analyze developmental mutations in Volvox by creating a separation method with dramatically increased resolution [28].

The most significant development for native protein complex analysis came in the early 1990s when Hermann Schägger and Gebhard von Jagow introduced Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE), specifically designed to isolate membrane protein complexes in enzymatically active form [29] [30]. This innovation addressed the critical limitation of SDS-PAGE, which denatures proteins and destroys non-covalently bound cofactors [8]. Continuous refinements throughout the 2000s, including standardized polymerization times and optimized protocols, further enhanced the technique's reliability and applications [27] [30].

Diagram 1: Historical development of electrophoresis techniques, showing the parallel development of denaturing and native approaches. The evolution culminated in BN-PAGE as a response to the limitations of fully denaturing methods.

Fundamental Principles: BN-PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

The core distinction between BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE lies in their fundamental mechanisms for imparting charge to proteins and their consequent effects on protein structure and complex integrity.

SDS-PAGE: Denaturing Separation

SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) employs the strong ionic detergent SDS, which denatures proteins and binds to them in a ratio of approximately 1.4g SDS per 1g protein [8]. This SDS coating imparts a uniform negative charge proportional to molecular mass, allowing separation primarily by size as proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix [8]. The method requires samples to be heated in the presence of SDS and reducing agents to fully denature proteins and break disulfide bonds [8]. While this enables excellent resolution and molecular weight determination, it destroys native protein structure, enzymatic activity, and non-covalent protein-protein interactions [8].

BN-PAGE: Native Complex Separation

BN-PAGE uses the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250 to coat proteins with the necessary negative charge for migration toward the anode [31]. Unlike SDS, Coomassie Blue does not denature protein complexes, allowing them to remain intact during electrophoresis [31]. Protein complexes separate according to their size and shape as they migrate through the porosity gradient of the acrylamide gel [31]. The technique employs mild nonionic detergents such as digitonin or n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside for membrane protein solubilization, which preserve native protein-protein interactions [32] [31]. This maintains enzymatic activity and the integrity of multi-protein complexes, enabling functional studies after separation [29].

NSDS-PAGE: A Hybrid Approach

A modified approach called Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) has been developed to address the limitations of both techniques [8]. This method reduces SDS concentration in running buffers from 0.1% to 0.0375%, eliminates EDTA from buffers, and omits the heating step [8]. Research demonstrates that NSDS-PAGE increases Zn²⁺ retention in proteomic samples from 26% to 98% compared to standard SDS-PAGE, with seven of nine model enzymes retaining activity after separation [8].

Table 2: Comparative Mechanism of BN-PAGE, SDS-PAGE, and NSDS-PAGE

| Parameter | BN-PAGE | SDS-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge Agent | Coomassie Blue G-250 | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Reduced SDS (0.0375%) |

| Protein State | Native | Denatured | Partially Native |

| Complex Integrity | Maintained | Disrupted | Variable Maintenance |

| Molecular Basis | Size & Shape | Molecular Mass | Molecular Mass & Structure |

| Typical Detergents | Digitonin, Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside | SDS, LDS | Reduced SDS |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | High (≥98%) | Low (∼26%) | High (∼98%) |

| Enzyme Activity Post-Electrophoresis | Preserved | Destroyed | Mostly Preserved |

Diagram 2: Decision framework for selecting electrophoresis methods based on research objectives. The choice between BN-PAGE, SDS-PAGE, and hybrid approaches depends primarily on whether native structure preservation or maximum resolution is prioritized.

Comparative Experimental Performance Data

Direct comparative studies provide quantitative evidence of the performance differences between electrophoresis techniques, particularly regarding preservation of enzymatic activity and metal cofactors.

Metal Retention and Enzymatic Activity

Research comparing SDS-PAGE, BN-PAGE, and NSDS-PAGE demonstrates dramatic differences in metal retention capability. When analyzing Zn²⁺ bound in proteomic samples, BN-PAGE and NSDS-PAGE achieved 98% metal retention, compared to only 26% with standard SDS-PAGE [8]. In functional studies with nine model enzymes, including four Zn²⁺ metalloproteins, all nine enzymes retained activity after BN-PAGE separation, while all were denatured during standard SDS-PAGE [8]. NSDS-PAGE showed intermediate performance, with seven of the nine enzymes retaining activity [8].

Resolution and Molecular Weight Range

SDS-PAGE typically provides superior resolution for individual protein subunits, effectively separating proteins differing by less than 2% in molecular mass [8]. BN-PAGE separates protein complexes ranging from 100 kDa to 10 MDa, with the effective range adjustable based on acrylamide gradient specifications [31]. While BN-PAGE has lower absolute resolution than SDS-PAGE, it successfully resolves complexes that would be disrupted in denaturing conditions [8].

Diagnostic Applications in Disease Research

BN-PAGE has proven particularly valuable in diagnosing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) defects. Research demonstrates that tissues from patients with severe OXPHOS deficiencies show almost complete absence of the corresponding enzyme band after catalytic staining in BN-PAGE gels [29]. In patients with partial deficiencies, a milder decrease in the enzyme band intensity is observed [29]. This application capitalizes on BN-PAGE's ability to maintain enzymatic activity post-separation, allowing direct in-gel activity staining for Complexes I, II, IV, and V [29] [30].

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Electrophoresis Techniques

| Performance Metric | BN-PAGE | SDS-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Cofactor Retention | 98% [8] | 26% [8] | 98% [8] |

| Enzyme Activity Preservation | 9/9 model enzymes [8] | 0/9 model enzymes [8] | 7/9 model enzymes [8] |

| Molecular Weight Range | 100 kDa - 10 MDa [31] | 5 - 250 kDa | Similar to SDS-PAGE |

| Resolution | Moderate | High | High |

| Protein Complex Integrity | Maintained | Disrupted | Partially Maintained |

| Diagnostic Reliability | High for OXPHOS defects [29] | Not applicable | Limited data |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

BN-PAGE Protocol for Protein Complex Analysis

The standard BN-PAGE protocol involves multiple carefully optimized steps to preserve native protein complexes:

Sample Preparation: Cells or tissues are solubilized using mild nonionic detergents such as digitonin (0.5-1%), n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (0.25-1%), or Triton X-100 (0.25-0.5%) in BN-PAGE sample buffer [32] [31]. The choice of detergent significantly impacts complex preservation, with digitonin being preferred for maintaining supercomplex organization [30]. The extraction is typically performed for 30 minutes at 4°C with gentle shaking, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove insoluble material [32].

Gel Electrophoresis: Linear gradient polyacrylamide gels (typically 4-16% acrylamide) are used to achieve optimal separation across a broad molecular weight range [31] [30]. Coomassie Blue G-250 is added to both the samples and the cathode buffer, providing the charge for electrophoretic migration while maintaining protein solubility [31] [30]. Electrophoresis is performed at constant voltage (typically 100-150V) for 90-95 minutes at 4°C to prevent heat denaturation [32] [30].

Detection Methods: Following electrophoresis, multiple detection approaches can be employed. Immunoblotting with specific antibodies enables identification of particular complexes [32]. Mass spectrometry provides comprehensive identification of complex components [25] [33]. In-gel enzymatic activity staining allows direct functional assessment of resolved complexes [29] [30].

Two-Dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE Protocol

For comprehensive analysis of protein complex composition, two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE combines native separation in the first dimension with denaturing separation in the second dimension:

First Dimension: Protein complexes are separated by BN-PAGE as described above [25] [33].

Dimension Transfer: Individual lanes from the BN-PAGE gel are excised and incubated in reducing LDS sample buffer containing 50 mM dithiothreitol for 30 minutes [32]. This step denatures the complexes and reduces disulfide bonds.

Second Dimension: The denatured strips are applied to standard SDS-PAGE gels for separation in the second dimension, resolving individual subunits by molecular mass [25] [33]. This approach enables identification of subunit composition within native complexes and has been successfully applied to analyze multi-protein complexes from various sources, including Helicobacter pylori and mitochondrial respiratory complexes [25] [33] [30].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful electrophoresis requires specific reagents optimized for each methodology. The table below details critical components and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Electrophoresis Techniques

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Modifying Agents | Coomassie Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge, maintains solubility | BN-PAGE [31] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins, imparts uniform charge | SDS-PAGE [8] | |

| Mild Detergents | Digitonin, n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside | Solubilizes membranes while preserving complexes | BN-PAGE [32] [31] |

| Strong Detergents | SDS, LDS | Complete solubilization and denaturation | SDS-PAGE [8] |

| Buffer Additives | 6-Aminocaproic acid, EDTA | Stabilizes proteins, chelates metals | BN-PAGE/SDS-PAGE [8] [30] |

| Gel Matrix Components | Acrylamide, Bis-acrylamide | Forms porous separation matrix | All Techniques |

| Enzyme Activity Stains | NADH, Nitrotetrazolium Blue | Detects dehydrogenase activity | BN-PAGE [29] |

| Lead nitrate, DAB | Detects cytochrome c oxidase activity | BN-PAGE [29] |

Applications in Contemporary Research

Mitochondrial Research and OXPHOS Analysis

BN-PAGE has become indispensable for mitochondrial research, enabling detailed analysis of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes and supercomplexes [29] [30]. The technique allows simultaneous assessment of all five OXPHOS complexes, with in-gel activity staining providing functional data complementary to protein abundance measurements [29]. This application has proven particularly valuable for diagnosing mitochondrial disorders, as BN-PAGE can detect specific complex deficiencies in patient tissues including heart, skeletal muscle, liver, and cultured fibroblasts [29].

Viral Membrane Protein Complexes

BN-PAGE has provided crucial insights into the organization of viral envelope glycoprotein complexes. Research on measles virus (MeV) demonstrated that native H complexes exist predominantly as loosely assembled tetramers in purified viral particles [32]. This application of BN-PAGE has helped elucidate the stoichiometric requirements for functional fusion complexes and the molecular mechanisms linking receptor binding with membrane fusion initiation [32].

Bacterial Multi-Protein Complexes

The method has been successfully applied to map protein interaction networks in bacterial systems. Studies of Helicobacter pylori identified 34 different proteins grouped in 13 multi-protein complexes, including both cytoplasmic and membrane complexes [33]. This approach revealed interactions between known pathogenic factors, such as urease with heat shock protein GroEL and CagA protein with DNA gyrase GyrA, providing insights into potential mechanisms of pathogenesis [33].

Protein-Protein Interaction Mapping

BN-PAGE serves as a powerful tool for comprehensive mapping of protein-protein interactions under native conditions. When combined with antibody shift assays, the technique can detect specific protein interactions directly within the gel matrix [25]. This capability has been leveraged to study complex dynamics in response to cellular stimuli, such as the changes in proteasome complexes following γ-interferon stimulation of cells [25].

Limitations and Technical Considerations

BN-PAGE Limitations

Despite its advantages, BN-PAGE presents several technical challenges. The requirement for clean and robust antibodies that recognize proteins in their native conformation can limit immunodetection options, as antibodies raised against denatured antigens may not bind effectively [31]. The Coomassie dye is not completely inert and may disrupt some weak protein-protein interactions, potentially leading to complex dissociation [31]. Additionally, the presence of salts or other solutes in samples can cause protein smearing during electrophoresis, requiring careful sample preparation and desalting [31].

Detection Limitations

While in-gel activity staining provides valuable functional data, its sensitivity varies between complexes. The comparative insensitivity of in-gel Complex IV activity staining and the complete lack of in-gel Complex III activity staining represent notable limitations for comprehensive OXPHOS analysis [30]. In tissues with high background staining, such as liver and cultured skin fibroblasts, evaluation of protein amount by conventional staining becomes difficult, necessitating immunoblotting after BN-PAGE separation [29].

Resolution Constraints

BN-PAGE provides lower absolute resolution compared to SDS-PAGE, which can make distinguishing between similarly sized complexes challenging [8]. This limitation may require troubleshooting of gradient gel parameters or implementation of two-dimensional approaches for adequate separation [31]. In cases where Coomassie dye interferes with analysis, Colorless Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) that lacks the anionic G-250 dye may be preferred [31] [30].

The historical development of electrophoresis reflects an ongoing effort to balance resolution with biological relevance. While SDS-PAGE revolutionized protein biochemistry by providing high-resolution separation of denatured polypeptides, BN-PAGE emerged as a complementary technique that preserves the functional organization of native protein complexes. The methodological comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that technique selection must be guided by specific research objectives: SDS-PAGE for maximum resolution of individual subunits, BN-PAGE for functional analysis of native complexes, and hybrid approaches like NSDS-PAGE for intermediate requirements. As electrophoretic methods continue to evolve, their integration with complementary analytical technologies promises to further expand our understanding of complex biological systems, maintaining their central role in biochemical research and diagnostic applications.

Practical Protocols: From Sample Prep to Specialized Applications

Step-by-Step BN-PAGE Protocol for Membrane Protein Complexes

Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) is a powerful technique designed to separate native protein complexes by molecular weight, preserving their functional integrity and enabling the study of protein-protein interactions. This stands in direct contrast to SDS-PAGE, which denatures proteins into their constituent polypeptides, thereby destroying native complexes and associated functional properties [8]. The core distinction lies in their applications: BN-PAGE is indispensable for analyzing the oligomeric state, stoichiometry, and native molecular weight of protein complexes, particularly those from membranes [34] [31], whereas SDS-PAGE is optimal for analyzing denatured protein subunits.

This guide provides a objective comparison of these techniques, with a detailed, experimentally-validated BN-PAGE protocol for the analysis of membrane protein complexes.

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in the mechanism by which proteins are prepared for electrophoretic separation.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Feature | BN-PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Coomassie dye imposes negative charge on native proteins [35] [31]. | SDS denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [8]. |

| Protein State | Native, intact complexes and oligomers [34]. | Denatured, individual polypeptide subunits [8]. |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Native molecular weight of the complex [31]. | Molecular weight of denatured subunits [8]. |

| Ideal Application | Studying protein-protein interactions, oligomeric state, and native complex composition [34] [36]. | Assessing protein purity, expression levels, and subunit composition via western blot [8]. |

| Key Limitation | Potential for mild disruption of some complexes by Coomassie dye; may require native-specific antibodies [31]. | Complete loss of native structure, function, enzymatic activity, and non-covalently bound cofactors [8]. |

A key advantage of BN-PAGE is its utility for membrane proteins. While SDS-PAGE and other solution-based methods like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) can be complicated by interference from detergent micelles, BN-PAGE effectively separates the protein-detergent complex from empty micelles, providing a more reliable assessment of monodispersity, a key indicator of sample quality for crystallization [34].

Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful BN-PAGE relies on specific reagents to solubilize and separate protein complexes in their native state.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for BN-PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge to protein surfaces for migration toward anode; prevents aggregation [35] [37]. | Must be the "G" (green) variant. The dye is considered non-denaturing but can disrupt some sensitive interactions [31]. |

| Mild Non-Ionic Detergents | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions [14]. | n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) and Digitonin are most common. Choice is critical for complex stability [34] [37]. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt used in extraction buffers; helps maintain protein integrity and supports solubilization [35]. | Provides a buffering environment at ~pH 7.0 without interfering with electrophoresis [35]. |

| Bis-Tris Buffer System | The standard buffer for BN-PAGE gel and running buffers, typically at pH 7.0 [35]. | Provides stable pH conditions crucial for maintaining native protein states during electrophoresis. |

| Gradient Gels | Separating gel with a gradient of increasing acrylamide concentration (e.g., 3-12%, 4-16%) [35]. | The molecular sieve separates complexes from ~100 kDa up to 10 MDa based on their size and shape [31]. |

Detailed BN-PAGE Experimental Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol is adapted from validated laboratory procedures for the analysis of membrane protein complexes [34] [35] [37].

Sample Preparation and Solubilization

- Membrane Isolation: Harvest biological material (cells, tissues) and isolate the membrane fraction using differential centrifugation. For cultured cells, wash pellets with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and freeze at -80°C until use [35].

- Solubilization: Thaw membrane pellets on ice. Solubilize by adding a non-ionic detergent. The optimal detergent and concentration must be determined empirically [14].

- Common detergents include 1-2% n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) for individual complexes or 2-4% Digitonin for labile supercomplexes [14] [37].

- The solubilization buffer should also contain 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors [34] [37].

- Incubate the solubilization mixture for 20-30 minutes on ice with gentle agitation.

- Clarification: Remove insoluble material by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 - 138,000 × g for 30-60 minutes at 4°C [34] [35].

- Sample Buffer Preparation: Mix the clarified supernatant with a BN-PAGE sample buffer. A typical 4X concentrated sample buffer contains 100 mM Bis-Tris, 100 mM 6-aminocaproic acid, 40% glycerol, and 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250 (added from a 5% stock solution in 500 mM 6-aminocaproic acid), pH 7.0 [35] [37].

Gel Electrophoresis

- Gel Casting: While pre-cast gradient gels are commercially available, manual casting of linear gradient gels (e.g., 3-12% or 4-16% acrylamide) is common [35]. The gel buffer is typically 150 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0.

- Loading and Running: Load the prepared samples onto the gel. Use native molecular weight markers for calibration.

- The anode buffer (lower chamber) is typically 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [35] [37].

- The cathode buffer (upper chamber) is initially the same as the anode buffer but supplemented with 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250 (Blue Cathode Buffer) or, for Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE), a mixture of anionic and neutral detergents to replace the dye [35] [37].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Run the gel at a constant voltage. For mini-gels, start at 100 V for 30-60 minutes until the sample has entered the gel, then continue at 150-200 V for 2-3 hours. The run should be performed at 4°C to maintain complex stability [35] [37].

Downstream Analysis

Following electrophoresis, the blue bands representing native protein complexes can be analyzed by several methods:

- In-Gel Activity Staining: Complexes remain active, allowing histochemical staining for enzymes like those in the oxidative phosphorylation system [35].

- Western Blotting: Transfer complexes to a PVDF membrane for immunodetection. Note that antibodies must recognize the native protein epitopes [31].

- Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis (2D-BN/SDS-PAGE): Excise a lane from the BN-PAGE gel, incubate it in SDS-PAGE sample buffer to denature the complexes, and place it horizontally on top of an SDS-PAGE gel. This resolves the individual protein subunits that make up each native complex, identified by mass spectrometry [36] [38].

BN-PAGE Experimental Workflow

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The choice between BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE has profound implications for experimental outcomes, especially concerning protein function and complex integrity.

Table 3: Experimental Outcomes and Performance Data

| Analysis Parameter | BN-PAGE Performance | SDS-PAGE Performance | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Cofactor Retention | High retention of non-covalently bound metal ions [8]. | Minimal retention (26% for Zn²⁺) [8]. | ICP-MS analysis of Zn²⁺ in proteome samples [8]. |

| Enzymatic Activity Post-Electrophoresis | High activity retention (9/9 model enzymes active) [8]. | No activity (all enzymes denatured) [8]. | In-gel activity assays for dehydrogenases, phosphatases, etc. [8]. |

| Membrane Protein Monodispersity Assessment | High correlation with crystallization success; effective separation of PDC from micelles [34]. | Not applicable for native state assessment. | Comparison with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) [34]. |

| Identification of ATP Synthase Complexes | Successful identification of intact F-type and V-type subcomplexes (~300 kDa) from C. thermocellum [38]. | Would only identify individual subunits (e.g., α, β ~55 kDa). | 2D BN/SDS-PAGE coupled with MALDI-TOF/TOF Mass Spectrometry [38]. |

A modified technique known as NSDS-PAGE demonstrates a potential middle ground, reducing SDS concentration and eliminating heating to retain some native properties while achieving resolution closer to SDS-PAGE [8]. This method retained Zn²⁺ in 98% of proteomic samples and preserved the activity of 7 out of 9 model enzymes [8].

BN-PAGE is an indispensable tool for the functional analysis of native protein complexes, particularly membrane proteins, while SDS-PAGE remains the standard for analytical separation of denatured proteins. The experimental data clearly shows BN-PAGE's superior ability to preserve protein function, complex integrity, and cofactor binding. For researchers studying protein-protein interactions, oligomeric states, and the functional architecture of macromolecular complexes, BN-PAGE provides critical insights that are completely lost in a standard SDS-PAGE analysis. The choice of technique should be decisively guided by the fundamental scientific question: the study of native structure and function requires BN-PAGE, while the analysis of denatured polypeptide composition is the domain of SDS-PAGE.

Standard SDS-PAGE Procedure for Denatured Protein Separation

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) represents the most widely employed technology for obtaining high-resolution analytical separation of complex protein mixtures. [8] This method revolutionized protein biochemistry when introduced in the 1970s and continues to serve as a fundamental technique in laboratories worldwide for assessing protein purity, evaluating expression patterns, and determining molecular mass. [8] [4] The technique's enduring popularity stems from its simplicity, reproducibility, and requirement for only microgram quantities of protein material. [39] [4]

Within the context of protein complex analysis, SDS-PAGE occupies a specific niche focused on denatured polypeptide separation, standing in direct contrast to blue-native PAGE (BN-PAGE), which preserves native protein complexes. This guide objectively examines the standard SDS-PAGE procedure, its experimental parameters, and its performance relative to BN-PAGE for specific applications in pharmaceutical and basic research settings.

Fundamental Principles of SDS-PAGE

Core Mechanism of Separation

SDS-PAGE separates proteins primarily based on molecular weight through a two-part mechanism involving protein denaturation and gel matrix sieving. [39] [4] The ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) denatures proteins by wrapping around the polypeptide backbone and conferring a uniform negative charge that overwhelms the protein's intrinsic charge. [4] Under reducing conditions that cleave disulfide bonds, proteins unfold into linear chains with charge proportional to polypeptide length. [39] These SDS-polypeptide complexes then migrate through a porous polyacrylamide gel matrix when an electrical field is applied, with smaller proteins moving faster due to less resistance from the gel matrix. [39] [4]

The polyacrylamide gel serves as a molecular sieve, with its pore size determined by the concentration of acrylamide bis-acrylamide. [4] The gel system typically employs a discontinuous buffer system with a stacking gel that concentrates proteins into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel, where separation primarily occurs. [39] [4] This combination of charge standardization and molecular sieving enables reliable molecular weight estimation when samples are compared to protein standards of known mass. [40]

Comparative Principle: BN-PAGE

In contrast to denaturing SDS-PAGE, blue-native PAGE separates proteins according to both net charge and mass while maintaining their native structure. [19] [4] BN-PAGE uses mild non-ionic detergents for solubilization and employs Coomassie Blue G250 to impart negative charges to protein complexes without disrupting subunit interactions. [19] [21] This preservation of quaternary structure allows BN-PAGE to separate intact protein complexes and supercomplexes, providing information about protein-protein interactions that is completely lost in SDS-PAGE. [19]

Table 1: Fundamental Separation Principles of SDS-PAGE vs. BN-PAGE

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Polypeptide molecular weight | Native mass, charge, and shape |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized | Native conformation preserved |

| Detergent Used | Denaturing ionic SDS (0.1-0.5%) | Mild non-ionic (dodecylmaltoside, digitonin, Triton X-100) |

| Charge Source | Bound SDS molecules | Coomassie Blue dye binding |

| Quaternary Structure | Destroyed | Maintained |

| Enzymatic Activity | Lost after separation | Often retained |

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

Reagent Preparation

The following research reagent solutions are essential for performing standard SDS-PAGE:

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE Experiments

| Reagent | Composition/Example | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution | 30% acrylamide, 0.8% bisacrylamide | Gel matrix formation through polymerization |

| SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer | 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.002% Bromophenol blue | Protein denaturation, charge impartation, and density for loading |

| Reducing Agent | β-mercaptoethanol (0.55M) or DTT | Disulfide bond reduction for complete unfolding |

| Running Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS | Conducts current and maintains SDS saturation |

| Resolving Gel Buffer | 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | Creates high-pH environment for separation |

| Stacking Gel Buffer | 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | Creates low-pH environment for protein stacking |

| Polymerization Initiators | APS (ammonium persulfate) and TEMED | Catalyze acrylamide polymerization |

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Gel Preparation: Assemble glass plates with spacers to form a cassette. For a standard 10% resolving gel, combine 7.5 mL of 40% acrylamide solution, 3.9 mL of 1% bisacrylamide, 7.5 mL of 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.7), water to 30 mL, 0.3 mL of 10% SDS, 0.3 mL of 10% APS, and 0.03 mL TEMED. [4] Pour between plates, overlay with water or isopropanol to ensure even polymerization, and allow to set for 20-30 minutes. Once polymerized, pour a stacking gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide in Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) and insert a comb to form wells. [39]

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing a reducing agent such as β-mercaptoethanol at a final concentration of 0.55M. [40] Heat samples at 95°C for 5 minutes (or 70°C for 10 minutes) to ensure complete denaturation. [39] [40] Centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 1-3 minutes to pellet any debris. [39] [40]

Electrophoresis: Mount the gel cassette in the electrophoresis chamber and fill with running buffer. Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers (5-35 μL per lane). [40] Apply constant voltage (150-200V) until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel (approximately 45-90 minutes). [8] [40]

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Following separation, proteins can be visualized using stains (Coomassie, silver staining), transferred to membranes for western blotting, or excised for mass spectrometric analysis. [4]

Comparative Performance Data: SDS-PAGE vs. BN-PAGE

Quantitative Comparison of Separation Outcomes

Direct comparison studies reveal fundamental performance differences between these techniques. In one systematic analysis, standard SDS-PAGE resulted in only 26% retention of bound Zn²⁺ in metalloproteins, while a modified native SDS-PAGE approach achieved 98% metal retention. [8] Similarly, when model enzymes were separated, all nine underwent complete denaturation and activity loss during standard SDS-PAGE, whereas all nine retained activity in BN-PAGE. [8]

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison Between Electrophoresis Methods

| Performance Metric | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Ion Retention | 26% | >90% | Zn²⁺ in metalloproteins [8] |

| Enzyme Activity Preservation | 0/9 enzymes active | 9/9 enzymes active | Model enzyme study [8] |

| Resolution of Complex Mixtures | High for polypeptides | Moderate for complexes | Proteomic separation [8] [19] |

| Suitable for Hydrophobic Membrane Proteins | Limited without special detergents | Excellent with optimized solubilization | Membrane protein complexes [14] [19] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Accurate for polypeptides | Approximate for native complexes | Comparative analysis [8] [19] |

Two-Dimensional Applications: BN-/SDS-PAGE

The complementary strengths of both techniques can be leveraged through two-dimensional electrophoresis. In this approach, protein complexes are first separated by BN-PAGE, then individual lanes are excised, soaked in SDS buffer, and placed atop an SDS-PAGE gel for second-dimension separation. [23] [21] This powerful method resolves both native complexes and their subunit composition, as demonstrated in studies identifying HNE-modified complex I subunits in diabetic kidney mitochondria. [23]

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Appropriate Use Cases for SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE remains the method of choice for applications requiring polypeptide-level resolution without need for native structure preservation. These include:

- Molecular Weight Determination: Estimation of protein subunit size relative to standards. [4] [40]

- Purity Assessment: Evaluation of protein preparation homogeneity during purification. [40]

- Expression Analysis: Comparison of protein expression levels across samples. [8]

- Western Blotting: Initial separation for immunodetection of specific proteins. [8] [4]

- Quality Control in Biopharmaceuticals: Purity analysis of biotherapeutic products using CE-SDS (capillary electrophoresis SDS), a related method. [41]

Limitations and Method Constraints

The fundamental limitation of SDS-PAGE lies in its deliberate denaturation of proteins prior to electrophoresis, which destroys functional properties including enzymatic activity, protein binding interactions, and non-covalently bound cofactors. [8] This makes it unsuitable for studying native protein complexes, protein-protein interactions, or enzymatic function after separation. Additionally, very large protein complexes (>500 kDa) may not enter standard gels effectively, while highly acidic or basic proteins may migrate anomalously due to residual charge effects. [40]

The choice between SDS-PAGE and BN-PAGE depends entirely on research objectives. SDS-PAGE provides superior resolution of denatured polypeptides by molecular weight and is ideal for standard protein characterization, purity assessment, and immunoblotting applications. In contrast, BN-PAGE preserves native protein structures and functions, enabling the study of protein complexes, interactions, and enzymatic activities. For comprehensive protein complex analysis, the two-dimensional BN-/SDS-PAGE approach offers the most complete information by combining the strengths of both techniques. Researchers must therefore align their electrophoretic method selection with their specific analytical needs—whether studying polypeptide composition or native protein function.

The analysis of protein complexes, particularly membrane-bound complexes, is a cornerstone of modern biological research and drug development. The choice of detergent for solubilizing these complexes is arguably the most critical factor determining the success of downstream analytical techniques, primarily Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and denaturing SDS-PAGE. These two techniques serve fundamentally different purposes: BN-PAGE separates intact protein complexes in their native state, preserving enzymatic activity and protein-protein interactions, while SDS-PAGE denatures complexes into individual subunits separated by molecular weight [42] [8]. Within this context, dodecylmaltoside, digitonin, and Triton X-100 have emerged as three of the most widely used detergents, each with distinct properties that influence experimental outcomes. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of these detergents to inform method development in protein complex analysis.

Detergent Properties and Performance Comparison

Key Characteristics and Recommended Applications

The table below summarizes the fundamental properties of these three detergents to guide initial selection.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Dodecylmaltoside, Digitonin, and Triton X-100

| Property | n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Digitonin | Triton X-100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Non-ionic, glycosidic | Non-ionic, steroid-based | Non-ionic, polyoxyethylene |

| Aggregation Number | 78-140 [43] | Mixture (natural product) | 100-155 [44] |

| Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | 0.0087% - 0.017% (w/v) [43] | ~0.2% (w/v) | 0.015% [44] |

| Typical Solubilization Concentration | 0.5-2% (w/v) [45] [43] | 1-4% (w/v) [45] [19] | 0.5-2% (w/v) [44] [19] |

| Primary Application in BN-PAGE | Solubilizing individual protein complexes with high activity [45] [19] | Preserving weak interactions and supercomplexes [45] [19] | General solubilization of membrane proteins [19] |

Experimental Performance Data

The functional performance of these detergents varies significantly in experimental settings, as evidenced by the following quantitative data.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison in Protein Complex Studies

| Performance Metric | n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Digitonin | Triton X-100 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Complex Activity Retention | High (e.g., active GABA receptors purified) [43] | High (e.g., PS synthase activity retained) [45] | Variable (can denature some complexes) [8] |

| Supercomplex Preservation | Low (typically dissociates supercomplexes) [19] | High (preserves respiratory supercomplexes) [19] | Low (typically dissociates supercomplexes) [19] |

| Enzymatic Activity Post-Electrophoresis | 7/9 model enzymes active after NSDS-PAGE [8] | N/A (often used in BN-PAGE where activity is retained) | N/A |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | 98% Zn²⁺ retained in NSDS-PAGE [8] | N/A | 26% Zn²⁺ retained in standard SDS-PAGE [8] |

| Solubilization Efficiency | Robust (>90% of membrane pellets) [43] | Effective for specific complexes [45] | Effective for general membrane proteins [44] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard BN-PAGE Protocol with Detergent Optimization

The following workflow outlines a standard BN-PAGE procedure, highlighting critical points for detergent selection and application.

Protocol Details:

- Sample Preparation: Harvest and wash 10x10⁶ cells in ice-cold PBS. Pellet cells by centrifugation at 350g for 5 minutes at 4°C [42].

- Solubilization: Resuspend the cell pellet in 250 µL of ice-cold BN-Lysis Buffer. Incubate on ice for 15 minutes. The key step is adding the selected detergent. Use a detergent-to-protein ratio that must be optimized empirically [19]:

- DDM: Often used at 1-2% (w/v) for solubilizing individual complexes.

- Digitonin: Typically 1-4% (w/v) for preserving supercomplexes.

- Triton X-100: Commonly 0.5-2% (w/v) for general membrane protein solubilization.

- Clarification and Dialysis: Centrifuge the lysate at 13,000g for 15 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material. Transfer the supernatant to a tube with a dialysis membrane (10 kDa cutoff) and dialyze against BN-Dialysis Buffer for 6 hours or overnight in the cold room [42]. This step removes salts and small metabolites that can interfere with electrophoresis.

- Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis: Pour a polyacrylamide gradient gel (e.g., 4-15%). Load the dialyzed lysate (1-40 µL) and appropriate native markers into the wells. Run the gel at 4°C, starting at low voltage (e.g., 100V for a minigel) until samples enter the separating gel, then increase to 180V until the dye front reaches the gel bottom [42].

- Analysis: For complexes separated by BN-PAGE, a second dimension SDS-PAGE can be performed. The BN-PAGE gel lane is incubated in SDS sample buffer, briefly heated, and then loaded onto an SDS gel to separate the individual subunits of the complex [42].

Case Study: Solubilizing Candida albicans Cho1 Protein

A 2023 study on solubilizing the transmembrane protein Cho1 from Candida albicans provides a direct comparison of detergent efficacy [45]. The research screened six non-ionic detergents and three styrene maleic acid copolymers. The results demonstrated that:

- Digitonin and DDM solubilized Cho1 effectively and were associated with the highest phosphatidylserine (PS) synthase activity.

- BN-PAGE and immunoblot analysis showed a single band for Cho1 in digitonin- and DDM-solubilized fractions.

- Further analysis via pull-down assays and electron microscopy indicated that the native Cho1 exists as a hexamer, a finding enabled by the gentle solubilization conditions.

This case underscores that while multiple detergents may achieve solubilization, the choice between DDM and digitonin is critical for retaining maximal enzymatic activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents required for experiments comparing detergents in protein complex analysis.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Detergent-Based Protein Complex Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Detergents | n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM), Digitonin, Triton X-100 | Solubilize membrane proteins while maintaining native protein-protein interactions to varying degrees. The core subject of comparison. |