Biomolecule Analysis Decoded: Harnessing Chromatography and Electrophoresis for Advanced Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the pivotal roles of chromatography and electrophoresis in biomolecule analysis.

Biomolecule Analysis Decoded: Harnessing Chromatography and Electrophoresis for Advanced Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the pivotal roles of chromatography and electrophoresis in biomolecule analysis. It covers foundational principles and explores the mechanisms of key techniques like HPLC, UHPLC, UHPLC, SDS-PAGE, and 2D-PAGE. The scope extends to methodological applications in characterizing complex therapeutics, practical troubleshooting for laboratory workflows, and rigorous validation and comparative analysis to inform technique selection. By synthesizing current advancements and practical insights, this resource aims to empower scientists in ensuring the safety, efficacy, and quality of next-generation biopharmaceuticals.

Core Principles: The Science Behind Separating Biomolecules

Chromatography is a foundational technique in analytical science for separating the individual components of a mixture. The process hinges on the differential distribution of analytes between two immiscible phases: a stationary phase and a mobile phase [1]. The mobile phase, which can be a liquid or a gas, serves to transport the sample mixture through the system. The stationary phase, typically a solid or a liquid supported on a solid, remains fixed in place [2]. Separation occurs because each component in the mixture interacts with these two phases with differing strengths, leading to distinct migration rates [3].

Components that exhibit stronger interactions with the stationary phase are retained longer, moving slowly through the system. Conversely, components with greater affinity for the mobile phase move through more rapidly [1]. This differential partitioning is the universal principle underlying all chromatographic techniques, from simple paper chromatography to advanced High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography (GC). The balance of intermolecular forces—such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and ionic attraction—between the analyte, mobile phase, and stationary phase dictates the efficiency and outcome of the separation [4] [3].

Theoretical Foundation: The Thermodynamics of Separation

The separation process in chromatography is governed by thermodynamic principles. The distribution of an analyte between the stationary and mobile phases is described by its partition coefficient, K, which is related to the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) for the transfer of the analyte from the mobile to the stationary phase [5]:

[\Delta G = -RT \ln K]

Here, R is the gas constant and T is the temperature in Kelvin. A more negative ΔG value signifies a stronger interaction with the stationary phase, resulting in a larger K and longer retention time for the analyte [4] [5].

The retention factor (k), a directly measurable parameter from the chromatogram, is related to the partition coefficient by (k = K \frac{Vs}{Vm}), where (Vs) and (Vm) are the volumes of the stationary and mobile phases, respectively [5]. The ultimate goal in chromatographic separation is to achieve resolution (Rs), which is a function of the retention factor (k), the column efficiency (N), and the selectivity (α) [4]. Selectivity, defined as the ratio of the retention factors of two adjacent peaks ((α = \frac{k2}{k1})), is a direct measure of the stationary phase's ability to distinguish between two analytes based on differences in their chemical properties [4].

Visualizing the Chromatographic Process

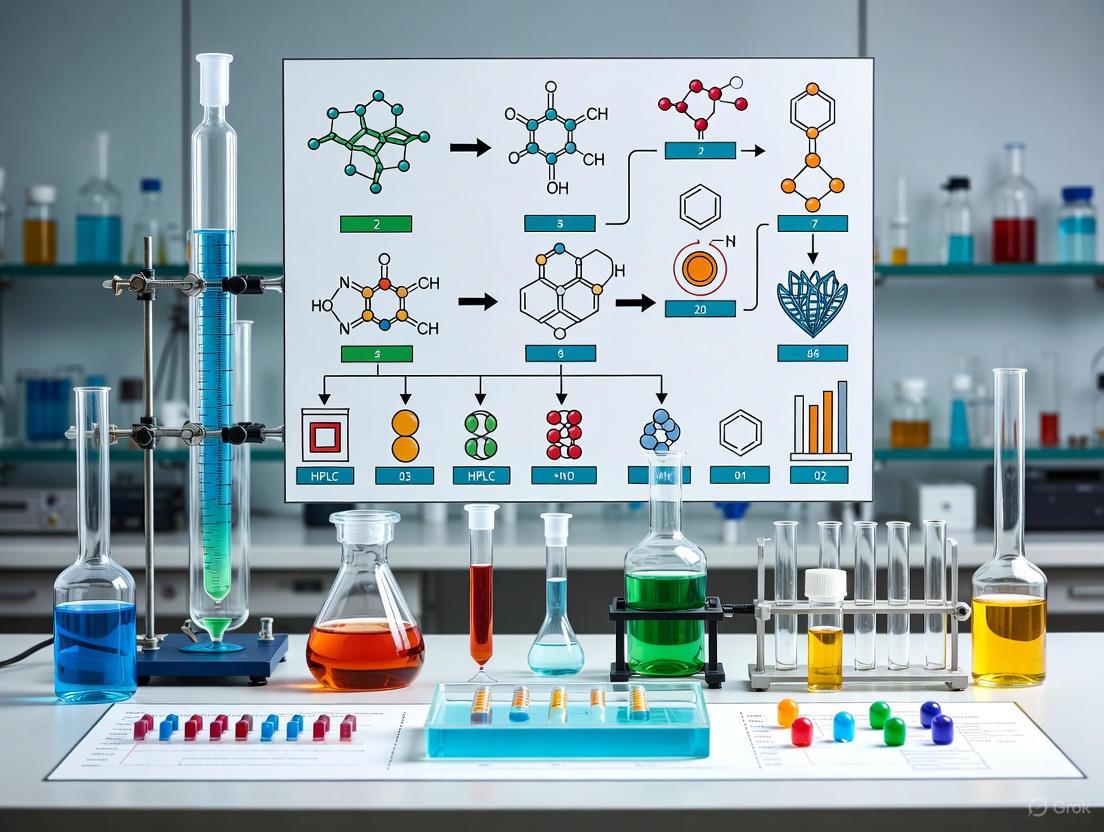

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental process of differential partitioning that leads to separation.

Defining the Two Phases: A Comparative Analysis

The careful selection and combination of the mobile and stationary phases are critical for developing a successful chromatographic method. Their properties directly determine the selectivity, efficiency, and speed of the separation. The table below summarizes their distinct roles and characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Roles and Properties of Mobile and Stationary Phases

| Parameter | Mobile Phase | Stationary Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Physical State | Liquid or Gas [2] [1] | Solid or Liquid immobilized on a solid support [2] [1] |

| Primary Function | Dissolves the sample and carries components through the system [2] | Interacts with components to retard their movement, effecting separation [2] |

| Common Examples | Solvents (e.g., water, methanol, acetonitrile), carrier gases (e.g., He, N₂) [2] [1] | Silica gel, alumina, chemically modified silica (C18, C8), gels, porous polymers [2] [1] [6] |

| Post-Process Handling | Often requires removal (evaporation) after separation [2] | Typically remains within the column for reuse [2] |

| Key Influence on Separation | Solvent strength/eluting power, pH, modifier additives [5] | Surface chemistry, functional groups, pore size, particle geometry [4] [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key materials and reagents essential for setting up and performing chromatographic separations, particularly in the context of biomolecule analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatography

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Silica-Based Sorbents | A versatile matrix used as-is in normal-phase chromatography or as a substrate for bonded phases in reversed-phase and other modes [6]. |

| Bonded Phases (C18, C8, Phenyl) | Silica chemically modified with alkyl or aryl chains to create hydrophobic surfaces for reversed-phase separation of non-polar to moderately polar molecules [6]. |

| Ion Exchange Resins | Stationary phases containing charged functional groups (e.g., quaternary ammonium for anion exchange, sulfonic acid for cation exchange) to separate biomolecules like proteins and nucleotides based on charge [1]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol, water) used to prepare the mobile phase; minimized impurities prevent column damage and detector noise [7]. |

| Buffers & Mobile Phase Additives | Salts (e.g., phosphate, acetate) and ion-pairing reagents (e.g., TFA) control pH and ionic strength, modulating analyte charge and interaction with the stationary phase [1] [5]. |

| Affinity Ligands | Specific biological molecules (e.g., antibodies, lectins, metal chelates) immobilized on the stationary phase to selectively capture target biomolecules like recombinant proteins [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments that illustrate the universal principle of mobile and stationary phase interaction.

Protocol 1: Analyzing Plant Pigments via Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC)

Purpose: To separate and identify chlorophylls and carotenoids from a leaf extract using TLC, demonstrating adsorption chromatography.

Materials and Reagents:

- TLC plates (silica gel, stationary phase)

- Mortar and pestle

- Fresh spinach leaves

- Organic solvent mixture (e.g., petroleum ether : acetone, 9:1 v/v, mobile phase)

- Developing chamber

- Capillary tubes

Procedure:

- Stationary Phase Preparation: Obtain a pre-coated silica gel TLC plate. Handle by the edges to avoid contamination.

- Sample Application: Using a capillary tube, spot the leaf extract onto the TLC plate approximately 1 cm from the bottom. Allow the spot to dry completely.

- Mobile Phase Introduction: Pour the prepared mobile phase into the developing chamber to a depth of about 0.5 cm. Seal the chamber to allow saturation with solvent vapor.

- Separation (Development): Place the spotted TLC plate vertically into the chamber, ensuring the sample spot is above the solvent level. Close the chamber.

- Termination and Visualization: Once the solvent front has migrated to near the top of the plate (∼15-20 minutes), remove the plate and immediately mark the solvent front. Allow the plate to dry. The separated pigments will appear as distinct colored bands.

Data Analysis: Calculate the retardation factor (Rf) for each pigment: [ R_f = \frac{\text{Distance travelled by pigment spot}}{\text{Distance travelled by solvent front}} ] Compare Rf values to standards for identification [3].

Protocol 2: Purification of a Synthetic Peptide by Reversed-Phase HPLC

Purpose: To purify a crude synthetic peptide mixture using gradient elution in Reversed-Phase HPLC.

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC system with binary pump, autosampler, and UV-Vis detector

- Reversed-Phase HPLC column (e.g., C18, 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm)

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile

- Syringe filters (0.22 µm)

- Crude peptide sample, dissolved in Mobile Phase A

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the crude peptide in Mobile Phase A. Filter the solution through a 0.22 µm syringe filter to remove particulate matter.

- Mobile Phase and System Preparation: Degas and prepare Mobile Phases A and B. Prime the HPLC system and equilibrate the column with 95% A / 5% B at the desired flow rate (e.g., 1.0 mL/min) until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Method Programming: Set the detector wavelength (e.g., 214 nm for peptide bonds). Program the gradient method:

- 0 min: 95% A, 5% B

- Over 30 min: linear gradient to 40% A, 60% B

- Hold for 5 min

- Return to initial conditions and re-equilibrate.

- Separation (Injection and Elution): Inject the filtered sample via the autosampler. Start the method. The hydrophobic peptide components will elute as the proportion of organic solvent (Mobile Phase B) increases.

- Fraction Collection: Monitor the chromatogram and use a fraction collector to collect the peak corresponding to the target peptide.

Data Analysis: Analyze the chromatogram to assess purity. The retention time of the main peak is characteristic under these specific mobile and stationary phase conditions [6].

Workflow for a Generic Biomolecule Purification

The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for a chromatographic purification, common to many of the protocols described.

Applications in Biomolecule Analysis and Drug Development

The interplay between mobile and stationary phases is exploited across various chromatographic modes to solve complex challenges in biomolecule analysis.

Pharmaceutical Quality Control: HPLC is a cornerstone for ensuring drug purity and stability. It is used to separate active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from synthetic impurities and degradation products. The selectivity offered by different stationary phases (e.g., C18, phenyl) and mobile phase compositions is critical for detecting low-level impurities [8] [6].

Protein and Enzyme Purification: Affinity Chromatography leverages highly specific biological interactions (e.g., antibody-antigen, enzyme-substrate) by immobilizing one binding partner (the ligand) on the stationary phase. This allows for the single-step purification of a target protein from a complex cellular lysate [1]. Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) separates biomolecules like proteins or nucleic acids based on their hydrodynamic volume, using a porous stationary phase for buffer exchange or oligomeric state analysis [1].

Metabolomics and Biomarker Discovery: In HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography), a polar stationary phase (e.g., bare silica or amide-bonded) is paired with a hydrophobic mobile phase (e.g., acetonitrile) to retain and separate highly polar metabolites that are poorly retained in reversed-phase HPLC. This is essential for comprehensive profiling of cellular metabolites [6].

Pharmacokinetic Studies: LC-MS (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) combines the separation power of HPLC with the identification capability of mass spectrometry. Here, the chromatographic mobile and stationary phases are optimized to resolve drugs and their metabolites from biological matrices, enabling quantification at very low concentrations in plasma or urine [9] [7].

The fundamental principle of chromatography—the differential partitioning of analytes between a moving mobile phase and a stationary phase—provides a powerful and versatile framework for the separation and analysis of complex mixtures. The careful selection and optimization of these phases, guided by the physicochemical properties of the target biomolecules, is the cornerstone of method development in research and industry. From the simple TLC plate to the sophisticated UHPLC-MS system, this universal principle enables scientists to ensure drug safety, advance biomedical research, and unlock the complexities of biological systems.

Within the broader field of biomolecule separation science, electrophoresis stands as a cornerstone technique, complementary to chromatography, for the analysis of nucleic acids, proteins, and other charged biological polymers. While chromatography separates molecules based on their differential partitioning between a mobile and a stationary phase, electrophoresis leverages the fundamental principles of charge, size, and the influence of an electrical field to achieve high-resolution separation [10]. This application note details the core principles and provides standardized protocols for gel electrophoresis, a foundational method critical for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in genomics, proteomics, and biopharmaceutical quality control.

Core Principles of Separation

At its core, electrophoresis is the motion of charged dispersed particles or dissolved charged molecules relative to a fluid under the influence of a spatially uniform electric field [11]. When applied to biomolecules in a gel matrix, this technique separates complexes based on key physical properties.

- Role of Net Charge: The direction of a molecule's migration in an electric field is determined by its net charge. In a standard setup, the electric field creates a positive electrode (anode) and a negative electrode (cathode). Consequently, a molecule with a negative net charge, such as DNA, whose phosphate backbone is negatively charged, will be attracted to and migrate towards the positive anode [12] [11].

- Influence of Size and Molecular Weight: The gel matrix, typically composed of agarose or polyacrylamide, acts as a molecular sieve. Its porous structure means that smaller molecules can navigate through the pores more easily and thus migrate faster over a given time, while larger molecules are impeded and travel more slowly [12] [13]. This results in the ordering of molecules by size.

- The Electrical Field as the Driving Force: The electrical field, defined by the voltage applied, provides the driving force for the movement of charged molecules. The electrophoretic mobility (μe), which defines the rate of migration, is described by the Smoluchowski equation:

μe = v/E = (εrε0ζ)/η, wherevis the drift velocity,Eis the electric field strength,εrandε0are dielectric constants,ζis the zeta potential, andηis viscosity [11]. In practice, higher voltages lead to faster migration but can compromise resolution, often necessitating optimization.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and logical relationships in a standard gel electrophoresis experiment:

Diagram 1: Gel electrophoresis workflow and principles.

Selection of Gel Matrix: Agarose vs. Polyacrylamide

The choice of gel matrix is critical and depends on the size of the target biomolecules and the required resolution. The tables below summarize the key differences and appropriate applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Agarose and Polyacrylamide Gel Properties

| Property | Agarose Gel | Polyacrylamide Gel (PAGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Polysaccharide from red algae [13] | Synthetic polymer [13] |

| Gel Formation | Dissolves in water and forms extensive hydrogen bonds [13] | Polymerizes in the presence of a crosslinking agent [13] |

| DNA Separation Range | 50 – 50,000 base pairs (bp) [13] | 5 – 3,000 bp [13] |

| Resolving Power | 5 – 10 nucleotides [13] | Single nucleotide [13] |

| Primary Use | Separation of larger DNA/RNA fragments [12] [13] | Separation of smaller nucleic acids or proteins; high-resolution applications [13] |

Table 2: Recommended Agarose Gel Percentages for DNA Separation

| Gel Percentage (%) | Range of Efficient Separation (base pairs) |

|---|---|

| 0.7 | 800 – 12,000 |

| 1.0 | 400 – 8,000 |

| 1.5 | 200 – 3,000 |

| 2.0 | 100 – 2,000 |

| 4.0 | 10 – 500 |

Data compiled from [13].

Table 3: Recommended Polyacrylamide Gel Percentages for DNA Separation

| Gel Percentage (%) (non-denaturing) | Range of Efficient Separation (base pairs) |

|---|---|

| 3.5 | 100 – 1,000 |

| 8.0 | 60 – 400 |

| 12.0 | 50 – 200 |

| 20.0 | 5 – 100 |

Data compiled from [13].

The relationship between gel percentage and fragment separation can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Gel percentage effects on separation.

Detailed Protocol: Agarose Gel Electrophoresis for DNA Analysis

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for separating DNA fragments using an agarose gel [12] [14].

Equipment and Reagents

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Agarose Gel Electrophoresis

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Agarose | Polysaccharide polymer that forms the porous gel matrix, acting as a sieve for separating molecules by size [13]. |

| TAE or TBE Buffer | Conducts the electric current and maintains a stable pH during the run. The buffer must be the same in the gel and the tank [12] [14]. |

| DNA Loading Dye | Contains a visible dye to track migration and glycerol to increase sample density, ensuring it sinks into the well [14]. |

| DNA Ladder (Marker) | A mixture of DNA fragments of known sizes, used to estimate the size of unknown DNA fragments in the sample [12]. |

| Ethidium Bromide or Safe Alternative | Fluorescent dye that intercalates with DNA, allowing visualization under ultraviolet (UV) light [14]. Caution: Ethidium bromide is a mutagen; handle with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) [14]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Gel Preparation

- Weigh and Mix: Weigh the appropriate amount of agarose powder (e.g., 1 g for a 1% gel in 100 mL of buffer) and mix with 1x TAE or TBE buffer in a microwave-safe flask [14].

- Dissolve Agarose: Heat the mixture in a microwave until the agarose is completely dissolved, swirling occasionally to ensure even heating. Take care to avoid boiling over [14].

- Cool and Add Stain: Let the solution cool to about 50°C (comfortable to touch). If using Ethidium Bromide, add it to a final concentration of ~0.2-0.5 μg/mL at this stage [14].

- Cast the Gel: Pour the molten agarose onto a casting tray with a well comb in place. Remove any bubbles with a pipette tip. Allow the gel to solidify completely at room temperature or 4°C [14].

Sample and Ladder Preparation

- Mix your DNA samples with loading buffer. A typical ratio is 5 µL of loading dye per 25 µL of DNA sample [14].

- Prepare the DNA ladder (marker) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Electrophoretic Run

- Once solidified, place the gel in the electrophoresis chamber and cover it with the same 1x buffer used to prepare the gel [14].

- Carefully remove the well comb.

- Load the DNA ladder into the first well. Load your prepared samples into the remaining wells.

- Secure the lid, ensuring the electrodes are correctly oriented (DNA, being negatively charged, will run towards the positive anode—"Run to Red") [12] [14].

- Apply an electrical current (typically 80-150 V). Run the gel until the dye front has migrated 75-80% of the way down the gel [14].

Visualization and Analysis

- Turn off the power and remove the gel from the tank.

- If not stained during preparation, the gel can be stained post-electrophoresis by soaking in a dye solution [14].

- Visualize the DNA bands using a UV transilluminator or blue light illuminator. Caution: Wear UV-protective eyewear [12] [14].

- Compare the position of your sample bands to the DNA ladder to estimate the size of the DNA fragments [12].

Applications in Biomolecule Analysis Research

Electrophoresis is indispensable in modern life science research and development. Its applications are vast and critical for drug development pipelines.

- Nucleic Acid Analysis: Gel electrophoresis is a fundamental technique for analyzing DNA and RNA. It is used to estimate the size and quantity of PCR products, verify products of cloning and gene editing, and check RNA integrity. DNA fingerprinting for forensic science and paternity testing also relies heavily on this technique [12] [15].

- Protein Analysis: Protein electrophoresis, particularly SDS-PAGE, separates proteins based on their molecular weight. It is a key tool for assessing protein purity, identifying proteins, and studying post-translational modifications, which is vital for characterizing biopharmaceuticals like monoclonal antibodies [15].

- Diagnostics and Clinical Research: Electrophoresis is used in medical diagnostics to detect genetic disorders, identify specific proteins in blood serum, and for the analysis of certain cancers, such as multiple myeloma, by detecting abnormal M proteins [12] [15].

- Drug Development and Quality Control: In the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, electrophoresis is crucial for quality control and assurance. It is used to analyze the purity, charge heterogeneity, and stability of protein-based therapeutics, ensuring they meet regulatory standards for safety and efficacy [15] [16].

Electrophoresis, governed by the straightforward yet powerful interplay of molecular charge, size, and an applied electrical field, remains an essential and versatile technique in the researcher's toolkit. Its ability to provide rapid, reliable separation and analysis of biomolecules makes it a fundamental pillar supporting advancements in genomics, proteomics, and the development of novel therapeutics. Mastery of its principles and protocols, as outlined in this application note, is fundamental for scientists engaged in biomolecule analysis.

Chromatography stands as a cornerstone technique in modern biomolecular research, enabling the separation, identification, and purification of complex biological mixtures. The power of chromatography lies in its diverse separation mechanisms, which exploit different physicochemical properties of molecules to achieve resolution. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these mechanisms is paramount for selecting the appropriate technique for specific analytical or purification challenges. This article details the five fundamental chromatographic separation mechanisms—adsorption, partitioning, ion exchange, size exclusion, and affinity—within the context of biomolecule analysis. By providing clear principles, application protocols, and practical optimization strategies, this guide serves as an essential resource for developing robust and reproducible chromatographic methods in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Each mechanism facilitates unique selectivity and is suited for particular classes of biomolecules. Adsorption chromatography separates based on surface binding, while partition chromatography relies on differential solubility between phases. Ion exchange chromatography exploits molecular charge, size exclusion chromatography separates by hydrodynamic volume, and affinity chromatography utilizes highly specific biological interactions. The choice of mechanism directly impacts the resolution, capacity, and success of downstream applications, from proteomic profiling to the purification of biotherapeutics.

The foundational principle of chromatography involves a stationary phase (a solid or liquid fixed in place) and a mobile phase (a liquid or gas that moves through or across the stationary phase). As the mobile phase carries the sample mixture, components interact differently with the two phases based on their chemical properties, leading to separation as they migrate at different velocities [1]. The specific nature of these interactions defines the separation mechanism.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Chromatographic Separation Mechanisms

| Separation Mechanism | Primary Basis for Separation | Key Biomolecule Applications | Critical Operational Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Polarity and surface binding affinity [1] | Small organic molecules, isomers [17] | Stationary phase surface activity, mobile phase polarity |

| Partitioning | Differential solubility/partitioning between two liquid phases [1] | Broad range of small molecules and pharmaceuticals [17] | Polarity of stationary vs. mobile phase (normal vs. reverse-phase) |

| Ion Exchange (IEX) | Net surface charge and charge density [18] [19] | Proteins, peptides, nucleic acids, amino acids [18] [19] | Mobile phase pH and ionic strength |

| Size Exclusion (SEC) | Molecular size (hydrodynamic radius) and shape [20] [21] | Protein aggregates, polymer separation, desalting [20] [21] | Pore size of stationary phase beads, column dimensions |

| Affinity | Specific biological interaction (e.g., ligand-receptor) [1] [17] | Antibodies, enzymes, recombinant tagged proteins [17] | Ligand specificity and binding conditions (pH, ionic strength) |

The separation process is universally represented by a chromatogram, which plots detector response against retention time. Each peak corresponds to a separated component, and the area under the peak can be used for quantification. The retention time (tᵣ)—the time taken for a compound to elute from the column—is a key identifying characteristic [1].

Diagram 1: Decision pathway for selecting chromatography mechanisms based on molecule properties.

Adsorption Chromatography

Principle and Theory

Adsorption chromatography, one of the earliest chromatographic methods, separates compounds based on their differential adsorption affinity to a solid stationary phase surface [1]. The mechanism involves the competition between analyte molecules and the mobile phase for binding sites on the adsorbent surface. Molecules with stronger adsorption to the stationary phase are retained longer and elute later, whereas weakly adsorbed components move faster with the mobile phase [1]. Common stationary phases include silica gel (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃), which possess polar surface groups. Silica gel has silanol (Si-OH) groups that can form hydrogen bonds and other dipole-dipole interactions with analytes [17]. The selectivity is primarily influenced by the polarity of the analyte molecules, with more polar compounds being more strongly retained on polar adsorbents.

Application Protocol: Separation of Plant Pigments by Adsorption Chromatography

Objective: To separate and identify chlorophylls, carotenes, and xanthophylls from a leaf extract using adsorption thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

Materials and Reagents:

- Stationary Phase: TLC plates coated with silica gel (250 µm thickness).

- Mobile Phase: Mixture of petroleum ether and acetone in a 9:1 ratio.

- Sample: Spinach or tomato leaf extract.

- Development Chamber: Glass tank with lid.

- Micropipette and capillary tubes.

- Sprayer for detection reagent.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind 2-3 grams of fresh leaves with 5 mL of acetone or ethanol using a mortar and pestle. Filter the extract through a plug of cotton or filter paper into a test tube.

- Spotting: Using a capillary tube, apply a small spot of the concentrated extract approximately 1.5 cm from the bottom edge of the TLC plate. Allow the spot to dry completely.

- Equilibration and Development: Pour the mobile phase into the development chamber to a depth of about 0.5 cm. Seal the chamber and allow it to saturate with solvent vapor for 10-15 minutes. Carefully place the spotted TLC plate into the chamber, ensuring the sample spot is above the solvent level. Replace the lid.

- Development: Allow the mobile phase to ascend via capillary action until it is about 1 cm from the top of the plate (typically 15-20 minutes).

- Visualization: Remove the plate from the chamber and immediately mark the solvent front with a pencil. Allow the plate to dry. The separated pigments will be visible as colored bands: chlorophylls (green), carotenes (yellow-orange), and xanthophylls (yellow).

Analysis: Calculate the Retention factor (Rf) for each pigment band using the formula: Rf = Distance traveled by solute / Distance traveled by solvent front. Compare the Rf values with standards for identification.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Mobile Phase Polarity: If separation is poor, adjust the mobile phase polarity. Increase the percentage of a more polar solvent (e.g., acetone or methanol) to decrease retention times of all compounds, or decrease it to increase retention.

- Stationary Phase Activity: The activity of adsorbents like silica gel can be affected by ambient humidity. Activating the plates by heating in an oven at 100-110°C for 30 minutes before use can improve reproducibility.

- Spot Tailing: This can occur if the sample is too concentrated or if there are strong, non-specific interactions with the stationary phase. Dilute the sample or use a more competitive mobile phase to reduce tailing.

Partition Chromatography

Principle and Theory

Partition chromatography separates compounds based on their differing solubilities in two immiscible liquid phases: the stationary phase and the mobile phase [1]. The stationary phase is a liquid immobilized on a solid support, and separation is governed by the partition coefficient (K), which is the ratio of the analyte's concentration in the stationary phase to its concentration in the mobile phase at equilibrium [1]. Compounds with a higher partition coefficient (more soluble in the stationary phase) are retained longer.

Partition chromatography is categorized into normal-phase and reverse-phase modes. In normal-phase partition chromatography, the stationary phase is polar (e.g., water, triethylene glycol) and the mobile phase is non-polar (e.g., hexane, chloroform). Thus, polar analytes are retained more strongly. In reverse-phase chromatography (RPC), which is far more common today, the stationary phase is non-polar (e.g., hydrocarbon chains like C8 or C18 bonded to silica) and the mobile phase is polar (e.g., water, methanol, acetonitrile). Consequently, hydrophobic (non-polar) analytes are retained more strongly in RPC [17].

Application Protocol: Reverse-Phase HPLC Analysis of Pharmaceutical Compounds

Objective: To separate and quantify the components of a pharmaceutical drug product using Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC).

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC System: Equipped with a pump, degasser, autosampler, column oven, and UV-Vis or Photodiode Array (PDA) detector.

- Column: C18 column (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size).

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water.

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile.

- Standards and Samples: Authentic drug standard and prepared drug product sample.

Procedure:

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Filter and degas both mobile phase A and B through a 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm membrane filter under vacuum with sonication.

- System Equilibration: Prime the system with the mobile phases. Set the initial mobile phase composition to 95% A and 5% B. Flow at 1.0 mL/min for at least 30 minutes or until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column Temperature: 30°C

- Detection Wavelength: 254 nm

- Injection Volume: 10 µL

- Gradient Program:

- 0 min: 95% A, 5% B

- 10 min: 50% A, 50% B

- 15 min: 5% A, 95% B

- 17 min: 5% A, 95% B

- 17.1 min: 95% A, 5% B

- 22 min: 95% A, 5% B (for re-equilibration)

- Analysis: Inject the standard and sample solutions. Identify peaks in the sample chromatogram by comparing their retention times with those of the standard. Quantify the active ingredient by integrating the peak area and comparing it to the calibration curve obtained from standards.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Gradient vs. Isocratic Elution: For mixtures with a wide range of hydrophobicities, a gradient elution (increasing the percentage of organic solvent over time) is essential. Isocratic elution is suitable for simple mixtures.

- Mobile Phase pH: Using buffers to control pH (e.g., phosphate or ammonium acetate) can significantly improve the peak shape of ionizable compounds by suppressing their ionization.

- Column Selection: C18 columns offer the strongest retention for non-polar compounds. For more polar analytes or for faster analysis, C8 or C4 columns can be used.

Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX)

Principle and Theory

Ion exchange chromatography separates ionizable compounds based on their net surface charge and its distribution under specified pH conditions [18] [19]. The stationary phase, known as the ion exchanger, contains covalently bound charged functional groups. These immobilized charges are associated with counter-ions of opposite charge that are in equilibrium with the mobile phase.

The two primary types of IEX are:

- Cation Exchange Chromatography: The stationary phase contains negatively charged functional groups (e.g., sulfonate, -SO₃⁻). It retains positively charged cations. The competition can be represented as: R-X⁻C⁺ + M⁺B⁻ ⇄ R-X⁻M⁺ + C⁺ + B⁻ [18].

- Anion Exchange Chromatography: The stationary phase contains positively charged functional groups (e.g., quaternary ammonium, -N(CH₃)₃⁺). It retains negatively charged anions. The competition is: R-X⁺A⁻ + M⁺B⁻ ⇄ R-X⁺B⁻ + M⁺ + A⁻ [18].

The binding of biomolecules like proteins to the ion exchanger is highly dependent on the mobile phase pH relative to the molecule's isoelectric point (pI). A protein will bind to a cation exchanger if the pH is below its pI (giving it a net positive charge), and to an anion exchanger if the pH is above its pI (giving it a net negative charge) [18]. Bound molecules are eluted by increasing the ionic strength of the mobile phase, which introduces competing ions that displace the analyte, or by changing the pH to neutralize the analyte's charge [18] [19].

Application Protocol: Anion Exchange Purification of a Recombinant Protein

Objective: To purify a recombinant protein (pI ~4.9) from a clarified E. coli lysate using anion exchange chromatography [22].

Materials and Reagents:

- Chromatography System: FPLC or HPLC system.

- Column: Anion exchange column (e.g., Q Sepharose Fast Flow, 1 mL column volume).

- Buffer A (Equilibration/Binding Buffer): 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

- Buffer B (Elution Buffer): 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 1 M NaCl.

- Sample: Clarified cell lysate in Buffer A.

Procedure:

- System and Column Preparation: Equilibrate the column with at least 5 column volumes (CV) of Buffer A until the UV baseline and conductivity are stable.

- Sample Preparation and Loading: Dilute the clarified lysate with Buffer A to ensure the conductivity is similar to that of Buffer A. Centrifuge or filter (0.22 µm) to remove any particulates. Load the sample onto the column at a moderate flow rate (e.g., 1 mL/min).

- Wash: Wash the column with 5-10 CV of Buffer A to elute unbound, non-negatively charged proteins and contaminants.

- Elution: Elute the bound target protein using a linear gradient from 0% to 100% Buffer B over 20 CV, or using a step gradient (e.g., elute with 20% B to remove weakly bound impurities, then with 50% B to elute the target protein). Collect fractions.

- Column Regeneration and Storage: Wash the column with 5 CV of 100% Buffer B to remove any tightly bound material, then re-equilibrate with 5 CV of Buffer A. Store the column according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Analysis: Analyze the collected fractions using SDS-PAGE for purity and a Bradford assay or UV absorbance for protein concentration.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Buffer pH Selection: Choose a buffer pH that ensures the target protein and the resin have opposite charges. For anion exchange, a pH at least one unit above the protein's pI is typical.

- Gradient Steepness: A shallow gradient provides better resolution of closely eluting species but takes longer. A steeper gradient is faster but may compromise resolution.

- Counter-ion Competition: The choice of salt (usually NaCl) in the elution buffer is common, but the type of ion can affect selectivity. For cations, the affinity for a cation exchanger generally follows: Li⁺ < H⁺ < Na⁺ < K⁺ [19].

Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

Principle and Theory

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC), also known as gel filtration or gel permeation chromatography, separates molecules based on their size in solution (hydrodynamic radius) and, to some extent, their shape [20] [21]. The stationary phase consists of porous beads with defined pore sizes. The key differentiator of SEC from other modes is that no adsorption occurs between the analyte and the stationary phase; separation is purely a physical sieving process [21].

The separation mechanism is governed by the access analytes have to the pore volume. Larger molecules that cannot enter the pores are excluded and elute first in the void volume (V₀). Smaller molecules that can enter the pores are retained longer and elute later. The total volume accessible to the smallest molecules is the total volume (Vₜ). The elution volume of a solute (Vₑ) is between V₀ and Vₜ [20]. The retention is expressed by the partition coefficient, KD = (Vₑ - V₀) / Vᵢ, where Vᵢ is the internal pore volume. KD ranges from 0 (for completely excluded molecules) to 1 (for molecules that can access all pores) [20].

Application Protocol: Analysis of Protein Aggregates by SEC

Objective: To separate and quantify monomeric and aggregated forms of a monoclonal antibody therapeutic using SEC [20].

Materials and Reagents:

- HPLC/UHPLC System: With an isocratic pump and UV detector.

- SEC Column: Silica-based or polymer-based column with appropriate pore size for proteins (e.g., 150 mm x 7.8 mm, 1.7-5 µm particles with ~300 Å pores).

- Mobile Phase: 100 mM Sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.8. Filter (0.22 µm) and degas.

- Samples: Monoclonal antibody reference standard and stressed/test sample.

Procedure:

- System Equilibration: Equilibrate the column with the mobile phase at a constant flow rate (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL/min for an analytical column) until a stable baseline is achieved. SEC is always performed under isocratic conditions.

- Calibration (Optional): Inject a mixture of globular proteins of known molecular weight (e.g., thyroglobulin, IgG, ovalbumin, myoglobin) to create a calibration curve of log(MW) vs. Vₑ.

- Sample Analysis: Inject a concentrated but low-volume protein sample (e.g., 10-20 µL of 1-2 mg/mL). Monitor the elution at 280 nm.

- Data Analysis: The chromatogram will show peaks corresponding to high molecular weight (HMW) aggregates (eluting first), the monomeric protein, and potentially fragments (eluting last). Integrate the peak areas to calculate the percentage of each species: % HMW = (Area_HMW / Total Area) × 100.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Minimizing Non-Ideal Interactions: Electrostatic interactions with residual silanols on silica-based columns can be mitigated by adding 100-150 mM salt to the mobile phase. Hydrophobic interactions can be reduced by adding a small percentage of organic modifier (e.g., 5% ethanol) or arginine [21].

- Flow Rate: Slower flow rates generally improve resolution by allowing for more equilibration between the mobile and stationary phases but increase analysis time [21].

- Sample Volume and Concentration: To avoid volume overloading and ensure optimal resolution, the injected sample volume should typically be 1-2% of the total column volume. High concentrations can cause viscosity effects, leading to peak broadening [21].

Table 2: Key Operational Parameters for Different Chromatography Types

| Parameter | Ion Exchange (IEX) | Size Exclusion (SEC) | Affinity | Reverse-Phase (RP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Load | Medium to High [19] | Low (volume-limited) [21] | Medium to High | Low to Medium |

| Mobile Phase | Aqueous buffer with salt gradient [18] [19] | Constant ionic strength buffer (isocratic) [20] | Binding buffer, then elution buffer [17] | Water/organic solvent gradient [17] |

| Critical Factor | pH and ionic strength [18] | Pore size and column volume [21] | Ligand specificity and binding conditions | Solvent strength and pH |

| Scale-Up | Excellent [19] | Good | Excellent | Good |

| Biomolecule Stability | Good (aqueous, can use pH/salt) | Excellent (non-interactive) [21] | Variable (elution can be denaturing) | Poor (organic solvents can denature) |

Affinity Chromatography

Principle and Theory

Affinity chromatography is a powerful technique that separates biomolecules based on a highly specific biological interaction between the target molecule and a ligand immobilized on the stationary phase [1] [17]. This is not based on general physicochemical properties like charge or size, but on lock-and-key interactions such as enzyme-substrate, antibody-antigen, receptor-hormone, or nucleic acid complementarity [17]. The process involves three main steps: 1) Binding/Adsorption, where the sample is applied and the target molecule binds specifically to the ligand while impurities pass through; 2) Washing, where unbound or weakly bound contaminants are removed; and 3) Elution, where the bound target molecule is released by altering conditions to disrupt the specific interaction [17]. Elution can be achieved by changing pH, increasing ionic strength, or using a competitive ligand (e.g., free substrate for an enzyme, or imidazole for immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) of His-tagged proteins).

Application Protocol: Purification of IgG Antibodies using Protein A/G Affinity Chromatography

Objective: To purify monoclonal or polyclonal IgG antibodies from cell culture supernatant or serum.

Materials and Reagents:

- Column: Pre-packed column with recombinant Protein A or Protein G agarose.

- Binding Buffer: 20 mM Sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0-7.5.

- Elution Buffer: 0.1 M Glycine-HCl, pH 2.5-3.0.

- Neutralization Buffer: 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5-9.0.

- Sample: Clarified cell culture supernatant or serum.

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Equilibrate the Protein A/G column with 5-10 CV of Binding Buffer.

- Sample Loading: Load the clarified sample onto the column at a slow flow rate to allow efficient binding.

- Washing: Wash the column with 10-15 CV of Binding Buffer until the UV absorbance returns to baseline, removing all non-specifically bound contaminants.

- Elution: Apply Elution Buffer to the column and collect 1 mL fractions into tubes containing 50-100 µL of Neutralization Buffer to immediately neutralize the low pH and preserve antibody activity.

- Column Regeneration and Storage: Wash the column with 5 CV of Binding Buffer, followed by 20% ethanol, and store at 4°C.

Analysis: Measure the absorbance of the collected fractions at 280 nm to determine protein concentration. Analyze purity by SDS-PAGE (reduced and non-reduced) and check functionality by ELISA or other activity assays.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- Ligand Leakage: A common issue is the leaching of the immobilized ligand into the eluted sample. Using resins with ligands covalently coupled via stable linkages can minimize this.

- Nonspecific Binding: If impurities co-elute with the target, increase the stringency of the wash buffer by adding a mild detergent (e.g., 0.01% Tween-20) or moderate salt concentration (e.g., 0.5 M NaCl) before elution.

- Harsh Elution Conditions: Low pH elution can denature some sensitive antibodies. Test gentler elution conditions, such as using a pH gradient or competitive eluents like ethylene glycol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Chromatography

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Ion Exchange Resins | Separation of charged biomolecules [18] [19] | Q Sepharose (Anion), SP Sepharose (Cation) |

| Size Exclusion Media | Separation by hydrodynamic size; desalting [20] [21] | Sephadex G-25, Superdex (for proteins) |

| Affinity Ligands | Highly specific purification [17] | Protein A/G (antibodies), Ni-NTA (His-tagged proteins) |

| Reverse-Phase Columns | Separation based on hydrophobicity [17] | C18, C8, C4 columns for HPLC/UHPLC |

| Buffers & Salts | Create and maintain the mobile phase environment | Tris, Phosphate buffers; NaCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄ |

| HPLC/UHPLC Systems | High-pressure, high-resolution analytical separation | Agilent, Waters, Shimadzu systems [1] |

Diagram 2: A multi-step purification workflow integrating different chromatographic techniques.

The five separation mechanisms—adsorption, partitioning, ion exchange, size exclusion, and affinity—provide a versatile toolkit for the analysis and purification of biomolecules. Each mechanism offers unique selectivity, and the choice depends on the target molecule's properties and the desired outcome. Ion exchange is unparalleled for charge-based separations, size exclusion is ideal for desalting and aggregate analysis without interaction, and affinity chromatography offers the ultimate purity for targets with specific binding partners. Partition chromatography, particularly in its reverse-phase mode, is a workhorse for analytical chemistry, while adsorption chromatography remains useful for specific applications.

Mastering these techniques involves understanding not only their core principles but also the practical aspects of method development, optimization, and troubleshooting. By strategically combining these techniques in a multi-step purification protocol, as illustrated in Diagram 2, researchers and drug development professionals can achieve the high levels of purity required for demanding applications in structural biology, functional studies, and biopharmaceutical development. The continued evolution of chromatographic media and instrumentation promises even greater resolution, speed, and sensitivity, further solidifying chromatography's central role in biomolecular research.

In the fields of chromatography and electrophoresis for biomolecule analysis, the ability to separate, identify, and quantify complex mixtures is fundamental. The analytical value of these techniques hinges on the analyst's ability to interpret key data outputs accurately. Among these, retention time, resolution, and efficiency are three pivotal parameters that collectively describe the quality and success of a separation [23] [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of these metrics is not merely academic; it is essential for developing robust methods, ensuring the purity of biopharmaceuticals like monoclonal antibodies, and making data-driven decisions during analysis [25] [26].

This application note details the core principles, quantitative relationships, and practical protocols for interpreting these critical parameters. The content is framed within the context of biomolecule analysis, providing a concrete foundation for optimizing separations in research and development.

Core Parameter Definitions and Mathematical Relationships

Fundamental Definitions

- Retention Time (tᵣ): The time elapsed between the injection of a sample and the detection of a specific analyte peak [24]. It is a characteristic identifier for an analyte under constant conditions, reflecting its interaction strength with the stationary phase (in chromatography) or its mobility in an electric field (in electrophoresis).

- Efficiency (N): A measure of the peak broadening in a system, expressed as the number of theoretical plates [23]. It is calculated from the peak width and retention time, with a higher N value indicating a narrower peak and a more efficient separation system [23] [27].

- Resolution (Rₛ): The degree of separation between two adjacent peaks [23] [24]. It is the ultimate metric for determining whether two components in a mixture can be quantified independently. Resolution is governed by the combined effects of efficiency, selectivity, and retention [27].

The Resolution Equation

The interdependence of retention time, efficiency, and selectivity is quantitatively described by the fundamental resolution equation [27]:

[ R_s = \frac{\sqrt{N}}{4} \times \frac{\alpha - 1}{\alpha} \times \frac{k}{1 + k} ]

Table 1: Terms in the Chromatographic Resolution Equation

| Term | Description | Impact on Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| N (Efficiency) | Number of theoretical plates; a measure of peak broadening. | Increased N (narrower peaks) leads to higher resolution. The relationship is proportional to the square root of N. |

| α (Selectivity) | The ratio of the retention factors of two adjacent peaks; a measure of the stationary phase's ability to distinguish between two analytes. | An increase in α (α > 1) dramatically improves resolution. Maximizing selectivity is often the most effective way to achieve separation. |

| k (Retention Factor) | Describes how long an analyte is retained on the column relative to the unretained solvent front. | Increasing k improves resolution, but the effect diminishes for k > 10. Very high k values lead to impractically long analysis times [27]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the experimental parameters and the resulting chromatographic resolution:

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Measurement and Optimization

Protocol 1: Measuring Retention Time and Calculating Efficiency

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for acquiring basic chromatographic data and calculating column efficiency.

1. Equipment and Reagents:

- HPLC or UHPLC system with UV/Vis or MS detector

- Appropriate chromatographic column (e.g., C18 for reversed-phase)

- Mobile phase solvents (HPLC grade)

- Standard analyte solutions

- Data acquisition software

2. Procedure: 1. Prepare the mobile phase according to the method specifications, ensuring it is properly filtered and degassed [23]. 2. Equilibrate the column with the starting mobile phase composition until a stable baseline is achieved. 3. Inject a standard solution of a single, well-characterized analyte. 4. Record the resulting chromatogram, noting the retention time (tᵣ) of the analyte peak and the width of the peak at its base (wb) or at half height (w{h/2}). 5. Calculate Efficiency (N): The number of theoretical plates can be calculated using one of the following formulae [27]: - Using peak width at base: ( N = 16 \times (tr / wb)^2 ) - Using peak width at half-height: ( N = 5.54 \times (tr / w{h/2})^2 )

3. Data Interpretation: A high N value indicates a highly efficient column with minimal band broadening. A low N value suggests issues such as column degradation, excessive extra-column volume, or poorly packed columns [23].

Protocol 2: Determining and Optimizing Chromatographic Resolution

This protocol describes how to calculate resolution between two analytes and provides a systematic approach for its optimization.

1. Equipment and Reagents:

- Same as Protocol 1.

- A solution containing two analytes that are not fully separated.

2. Procedure: 1. Follow steps 1-3 from Protocol 1 using the mixture of two analytes. 2. From the chromatogram, measure the retention times for the two peaks (tᵣ₁ and tᵣ₂) and their respective peak widths at the base (wb1 and wb2). 3. Calculate Resolution (Rₛ): Use the standard formula [24]: [ Rs = \frac{2(t{r2} - t{r1})}{w{b1} + w_{b2}} ] 4. Optimization Strategy: If Rₛ is less than 1.5 (indicating incomplete baseline separation), systematically adjust method parameters: - To Increase Efficiency (N): Use a column with smaller particle sizes or reduce extra-column volume [23]. - To Increase Selectivity (α): Modify the mobile phase composition (e.g., pH, solvent type) or change the column chemistry [23] [26]. - To Adjust Retention Factor (k): Alter the solvent strength of the mobile phase (e.g., % organic modifier in reversed-phase HPLC) [27].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Suboptimal Resolution

| Observation | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low efficiency (broad peaks) | Column degradation, excessive extra-column volume, poorly packed column. | Replace column, use narrower tubing, check system configuration [23]. |

| Poor selectivity (peaks co-elute) | Mobile phase or stationary phase not suited for the analytes. | Adjust mobile phase pH or solvent composition; change column type (e.g., from C18 to phenyl) [23] [26]. |

| Retention too weak or too strong | Incorrect solvent strength in mobile phase. | Adjust the gradient or isocratic composition of the mobile phase [23]. |

Protocol 3: Charge Variant Analysis of Monoclonal Antibodies via Cation-Exchange Chromatography (CEX)

The analysis of charge variants is a critical quality attribute for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) in biopharmaceutical development [25] [26].

1. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 3: Essential Materials for CEX-MS of mAbs

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Cation-Exchange Column | Stationary phase with negative surface charge to separate mAb variants based on electrostatic interactions [26]. |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffers | MS-compatible volatile salts for the mobile phase, enabling both separation and subsequent mass spectrometry detection [25]. |

| Acetonitrile (with additive) | Organic modifier (typically 2%) added to the mobile phase to improve peak shape and ionization efficiency [25]. |

| Intact mAb Standard | Sample for method development and system suitability testing. |

2. Procedure: 1. Mobile Phase Preparation: Prepare eluent A (e.g., 50 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.0) and eluent B (e.g., 100-160 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.5), each with 2% acetonitrile [25]. 2. Column Equilibration: Equilibrate the CEX column with the starting conditions (e.g., 55% B) [25]. 3. Gradient Elution: Inject the mAb sample and run a linear gradient (e.g., from 55% B to 85% B over 25 minutes at a low flow rate of 0.1 mL/min) to elute the variants [25]. 4. Detection: Use online UV detection at 280 nm. The acidic variants elute first, followed by the main species, and then the basic variants. 5. MS Coupling: The volatile ammonium acetate buffer allows the eluent to be directly coupled to a mass spectrometer for identification of the specific proteoforms (e.g., lysine variants, glycosylation patterns) responsible for the charge heterogeneity [25].

The following workflow diagram maps the logical sequence of this protocol:

Advanced Data Analysis Techniques

Modern chromatography increasingly leverages advanced data analysis to extract more information from complex datasets, particularly in the analysis of biomolecules.

- Multivariate Analysis: Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are used for data reduction and pattern recognition in complex chromatographic fingerprints, such as in metabolomics studies. PCA can transform a large number of correlated variables (e.g., signal intensities across time) into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components, allowing for the classification of samples or identification of biomarkers [28].

- Machine Learning: Algorithms are being applied to tasks such as automated peak detection and chromatogram classification. This can significantly reduce the need for manual integration and provide objective, high-throughput analysis of chromatographic data, such as classifying pharmaceutical samples based on their profiles [28].

A rigorous understanding of retention time, resolution, and efficiency is the cornerstone of effective method development and data interpretation in biomolecule analysis. By applying the fundamental resolution equation and the systematic optimization strategies outlined in these protocols, researchers can significantly improve their analytical methods. The presented protocols for efficiency measurement and charge variant analysis of mAbs provide a concrete framework applicable to real-world challenges in drug development. As the field advances, the integration of sophisticated data analysis techniques like multivariate analysis and machine learning will further empower scientists to derive deeper insights from their chromatographic and electrophoretic data.

Technique Deep Dive: Applying LC, CE, and PAGE in Biopharmaceutical R&D

Liquid chromatography (LC) has stood as a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry for over a century, undergoing remarkable technological evolution to meet increasingly complex analytical demands. This evolution from traditional liquid chromatography to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and ultimately to ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) represents a paradigm shift in separation science, driven by advancements in pressure capabilities, stationary phase chemistry, and instrumentation design. Within biomolecule research—including protein characterization, peptide mapping, and biopharmaceutical development—these techniques provide indispensable tools for separating, identifying, and quantifying components in complex mixtures [29]. The migration toward advanced chromatographic systems has fundamentally transformed research capabilities in drug development, enabling higher throughput, superior resolution, and enhanced sensitivity for critical quality attributes assessment. This application note delineates the technical progression of liquid chromatography technologies, provides structured comparative analysis, and details practical protocols tailored for biomolecule analysis within the broader context of chromatography and electrophoresis research.

Historical Progression and Technological Evolution

The journey of liquid chromatography began in the early 20th century with the pioneering work of Russian botanist Mikhail Tsvet, who first demonstrated the separation of plant pigments using a liquid solvent percolating through a solid adsorbent in a column [29]. This traditional liquid chromatography (LC) operated under low pressure, often relying on gravity for mobile phase propulsion, which resulted in protracted analysis times and limited resolution. Despite its foundational role, traditional LC proved inadequate for complex separations due to its reliance on larger, irregularly packed stationary phase particles.

A transformative advancement occurred in the 1970s with the emergence of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), which revolutionized the field through the incorporation of high-pressure pumps capable of operating up to 6,000 psi (400 bar) and columns packed with smaller, uniformly sized particles (typically 3-5 μm) [30] [29]. This technological leap significantly enhanced separation efficiency, resolution, and analysis speed, establishing HPLC as the analytical standard across pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical laboratories.

The continued pursuit of higher efficiency and faster analysis culminated in the commercial introduction of ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) in 2004, marked by Waters Corporation's trademarked Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) system [31]. UHPLC technology leverages sub-2-micron particles and specialized instrumentation engineered to withstand extreme pressures up to 19,000 psi (1,500 bar) [32] [29]. These advancements enable superior resolution, reduced solvent consumption, and dramatically shortened run times, making UHPLC particularly valuable for high-throughput environments and the analysis of highly complex biomolecular samples.

Figure 1: The evolution of liquid chromatography from traditional LC to UHPLC, highlighting key technological advancements at each stage.

Technical Comparison of LC, HPLC, and UHPLC

The fundamental differences between LC, HPLC, and UHPLC systems manifest across several technical parameters that directly impact their analytical capabilities and application suitability. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for selecting the appropriate technique for specific research requirements.

Core Technical Parameters

Table 1: Comparative technical specifications of LC, HPLC, and UHPLC systems

| Parameter | Traditional LC | HPLC | UHPLC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Pressure | Low pressure (gravity-driven) | Up to 6,000 psi (400 bar) [30] | 15,000-19,000 psi (1,000-1,300 bar) [30] [32] |

| Particle Size | Large, irregular particles (≥10 μm) [29] | 3-5 μm [30] | <2 μm [30] [29] |

| Analysis Speed | Slow (hours) | Moderate (minutes to hours) | Fast (typically minutes) [29] |

| Separation Efficiency | Low resolution | High resolution | Very high resolution [29] |

| Sensitivity | Low | Moderate | High [30] |

| Sample Volume | Larger volumes | Moderate volumes | Small volumes [30] |

| Solvent Consumption | High | Moderate | Low [29] |

| Theoretical Plates | Low | High | Very high |

| Column Lifespan | Long | Long | Shorter due to higher pressures [30] |

| Instrument Cost | Low | Moderate | High [32] |

Operational Considerations for Biomolecule Analysis

The selection of an appropriate chromatographic technique must align with specific research objectives, sample characteristics, and operational constraints. HPLC remains the workhorse for routine analyses where extreme resolution or minimal analysis time are not critical factors. Its robust nature, lower operational costs, and compatibility with a wide range of established methods make it ideal for quality control environments and standardized assays [32]. The larger particle size in HPLC columns (3-5 μm) contributes to longer column lifespan and reduced susceptibility to clogging, which is particularly advantageous when analyzing complex biological matrices [30].

UHPLC excels in research scenarios demanding maximum resolution, speed, and sensitivity. The implementation of sub-2-micron particles provides significantly increased surface area for interactions, resulting in superior separation efficiency [29]. This enhanced performance is particularly valuable for characterizing complex biomolecular mixtures, such as proteomic digests, antibody-drug conjugates, and glycan profiles, where subtle structural differences must be resolved [33]. The reduced solvent consumption of UHPLC systems also lowers operational costs and environmental impact over time, though this must be balanced against higher initial capital investment and more stringent maintenance requirements [32] [31].

Application Protocols for Biomolecule Analysis

Protocol 1: Peptide Mapping and PTM Analysis Using RP-UHPLC/MS

Principle: Reversed-phase liquid chromatography separates peptides based on hydrophobicity, enabling resolution of proteolytic fragments and identification of post-translational modifications (PTMs) when coupled with mass spectrometry [33].

Sample Preparation:

- Denaturation: Dilute protein to 1 mg/mL in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0.

- Reduction: Add dithiothreitol to 5 mM final concentration, incubate at 56°C for 30 minutes.

- Alkylation: Add iodoacetamide to 15 mM final concentration, incubate in dark at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Digestion: Add trypsin at 1:20 (w/w) enzyme-to-substrate ratio, incubate at 37°C for 4-16 hours.

- Quenching: Acidify with 1% formic acid to pH <3, centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- System: UHPLC with mass spectrometry compatibility

- Column: C18, 1.0 × 150 mm, 1.7 μm particles

- Mobile Phase A: 0.1% formic acid in water

- Mobile Phase B: 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Gradient: 2-35% B over 60 minutes, 35-80% B over 5 minutes, hold at 80% B for 5 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.2 mL/min

- Temperature: 45°C

- Injection Volume: 5-10 μL

- Detection: UV at 214 nm and MS with ESI positive mode

Data Analysis: Identify peptides by database searching of MS/MS spectra. Quantify PTMs by extracted ion chromatograms of modified vs. unmodified peptides.

Protocol 2: Charge Variant Analysis by Ion Exchange Chromatography

Principle: Cation exchange chromatography separates protein variants based on differences in surface charge, enabling characterization of charge heterogeneity in biopharmaceuticals [33].

Sample Preparation:

- Buffer Exchange: Dialyze or desalt protein sample into 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.0.

- Concentration Adjustment: Dilute or concentrate sample to 1 mg/mL in loading buffer.

- Clarification: Filter through 0.22 μm centrifugal filter.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- System: HPLC or UHPLC with high-pressure mixing capability

- Column: Strong cation exchanger (SO3-), 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm particles for HPLC; 2.1 × 100 mm, 3 μm particles for UHPLC

- Mobile Phase A: 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.0

- Mobile Phase B: 20 mM sodium phosphate, 500 mM NaCl, pH 6.0

- Gradient: 0-50% B over 30-45 minutes

- Flow Rate: 0.8 mL/min (HPLC) or 0.4 mL/min (UHPLC)

- Temperature: 25°C

- Injection Volume: 10-20 μL

- Detection: UV at 280 nm

Data Analysis: Integrate peak areas for individual charge variants. Compare relative percentages across different batches or formulations.

Protocol 3: Aggregate Analysis by Size Exclusion Chromatography

Principle: Size exclusion chromatography separates molecules based on hydrodynamic radius, enabling quantification of protein aggregates and degradation fragments [33].

Sample Preparation:

- Formulation Matching: Prepare sample in formulation buffer or 100 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0.

- Centrifugation: Clarify by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Concentration: Adjust to 1-2 mg/mL using an appropriate concentrator.

Chromatographic Conditions:

- System: HPLC with isocratic capability

- Column: SEC column, 7.8 × 300 mm, 5 μm particles

- Mobile Phase: 100 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.0

- Flow Rate: 0.5-1.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 25°C

- Injection Volume: 10-25 μL

- Detection: UV at 280 nm, optional multi-angle light scattering (MALS)

Data Analysis: Calculate percentage of high molecular weight species and fragments relative to main peak. For MALS detection, determine absolute molecular weights.

Figure 2: Generalized workflow for chromatographic analysis of biomolecules, highlighting critical steps from sample preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of chromatographic methods requires careful selection of consumables and reagents optimized for specific separation goals. The following toolkit outlines essential materials for biomolecule analysis using liquid chromatography techniques.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for liquid chromatography of biomolecules

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| C18 Column | Reversed-phase separation of peptides and small proteins [33] | 1.7-5 μm particles; 50-150 mm length; 1.0-4.6 mm ID | Particle size determines efficiency and backpressure; smaller IDs enhance MS sensitivity |

| Cation Exchange Column | Charge variant analysis of monoclonal antibodies and proteins [33] | SO3- functional groups; 3-5 μm particles; 50-100 mm length | Select strong vs. weak exchanger based on target protein pI and stability |

| Size Exclusion Column | Aggregate and fragment analysis [33] | 5 μm particles; 150-300 mm length; appropriate separation range | Pore size should match target protein molecular weight |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Water | Mobile phase preparation for LC-MS | Low organic content, <0.1 μm filtered | Essential for minimizing background noise in MS detection |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Acetonitrile | Organic modifier for reversed-phase LC-MS | Low UV cutoff, low residue after evaporation | Higher purity reduces system contamination and background noise |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Ion-pairing reagent for improved peptide separation | HPLC grade, ≥99.8% purity | Use at 0.05-0.1% in mobile phases; can suppress MS signal |

| Formic Acid | Mobile phase acidifier for LC-MS applications | LC-MS grade, ≥99.5% purity | Typically used at 0.1%; MS-compatible alternative to TFA |

| Ammonium Acetate | Volatile buffer for LC-MS separations | HPLC grade, ≥99.0% purity | Useful for IEX-MS applications; concentration typically 10-50 mM |

| Vial Inserts | Minimize sample volume for limited samples | Glass or polymer with 100-250 μL capacity | Low-volume inserts essential for sample-limited biomolecule studies |

| 0.22 μm Filters | Sample clarification and mobile phase filtration | PVDF or nylon membrane | Critical for protecting columns from particulates, especially in UHPLC |

Implementation Considerations for Research Laboratories

System Selection and Method Transfer

The choice between HPLC and UHPLC involves careful consideration of analytical requirements, sample throughput, and available resources. HPLC systems offer a robust, cost-effective solution for routine analyses with well-characterized methods, providing greater tolerance for sample matrix effects and lower operational costs [32]. The ruggedness of HPLC methodology makes it particularly suitable for laboratories with varying operator experience levels or those analyzing diverse sample types with potential particulate contaminants.

UHPLC systems deliver superior performance for method development, high-throughput screening, and complex separation challenges, but require higher initial investment and more meticulous operation [32]. The enhanced resolution and sensitivity of UHPLC comes with increased demands for sample cleanliness, higher quality solvents, and more frequent system maintenance [31]. Method transfer from HPLC to UHPLC necessitates careful optimization to account for differences in dwell volume, pressure limitations, and detection parameters, though the fundamental separation chemistry remains consistent [29].

Integration with Electrophoretic Techniques in Biomolecule Research

Within comprehensive biomolecule characterization strategies, liquid chromatography functions synergistically with electrophoretic methods to provide orthogonal analytical data. While chromatography excels at separating molecules based on chemical properties (hydrophobicity, charge, size), electrophoresis offers complementary separation based on size (SDS-PAGE, CE-SDS) or charge (IEF, icIEF) [33]. The integration of these techniques provides a more complete molecular profile for complex biologics, enabling comprehensive assessment of attributes including purity, heterogeneity, and product quality.

For instance, size exclusion chromatography may be coupled with CE-SDS to corroborate aggregation and fragmentation profiles, while ion exchange chromatography and icIEF deliver complementary charge heterogeneity data [33]. This multi-analytical approach is particularly valuable in biopharmaceutical development, where comprehensive characterization of product quality attributes is required by regulatory authorities. The selection of appropriate technique combinations should be guided by the specific molecular attributes under investigation and the required level of analytical precision.

The evolution from LC to HPLC and UHPLC represents a continuous trajectory toward higher efficiency, faster analysis, and superior resolution in biomolecule separation science. While each technological iteration maintains the fundamental principles of liquid chromatography, their distinct operational parameters and performance characteristics dictate specific application suitability. HPLC remains the versatile workhorse for routine analyses and quality control, whereas UHPLC provides cutting-edge capabilities for complex separation challenges and high-throughput environments. Understanding the technical distinctions, practical implementation requirements, and complementary nature of these chromatographic techniques empowers researchers to make informed decisions that optimize analytical outcomes in biomolecule research. As liquid chromatography continues to evolve alongside advances in column chemistry, detection technology, and data analysis, its role as a foundational tool in biomolecular analysis remains firmly established.

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) is a powerful, liquid-based separation technique that has matured into a robust analytical tool complementary to High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). While both techniques are capable of separating complex mixtures, they are based on fundamentally different principles. HPLC separations are primarily governed by the partitioning of analytes between a stationary and a mobile phase, whereas CE separates ions based on their electrophoretic mobility under the influence of a high-voltage electric field within a capillary tube [34]. This core difference makes the two techniques orthogonal, meaning CE can often separate compounds that are challenging for HPLC and vice versa [35]. The growth of the biopharmaceutical industry, where CE methods are now embedded in pharmacopoeial monographs, has been a key driver in cementing CE's role in the modern analytical laboratory [34]. This application note details how CE serves as a complementary and often lower-cost alternative to HPLC, with a specific focus on the analysis of biomolecules for research and drug development.

Comparative Advantages and Market Context

The choice between CE and HPLC involves a multi-faceted assessment of analytical performance, practical efficiency, cost, and environmental impact. A comparative evaluation using the RGB model (Red: analytical performance, Green: eco-friendliness, Blue: practical/economic efficiency) illustrates that CE frequently scores highly in the green and blue categories, offering a more sustainable and cost-effective operation [36]. A key advantage of CE is its minimal consumption of samples and solvents; separations are typically performed in capillaries with volumes of about 1 µL, with only nanoliters of sample injected, leading to very low generation of chemical waste [34].

Market Growth and Application Segments (2025-2035)

| Segment | Market Size (2025) | Projected Market Size (2035) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Primary Application in Biomolecule Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global CE Market [37] | USD 1.2 Billion | USD 2.1 Billion | 5.8% | - |

| DNA Sequencing & Fragment Analysis [37] | ~38% of CE revenue | - | - | Sanger verification, genotyping, NGS library QC |

| Protein & Peptide Characterization [37] | ~27% of CE revenue | - | - | mAb characterization, charge variant analysis (cIEF), purity (CE-SDS) |

| Drug Impurity & Stability Profiling [37] | - | - | 7.0% | Purity profiling of complex biologics, oligonucleotide therapies |

| Clinical Diagnostics [37] | - | - | 6.5% | Hemoglobinopathy screening, minimal residual disease monitoring |

The technique's versatility is reflected in its robust market growth, particularly in applications like nucleic acid analysis, which remains the largest revenue segment, and drug impurity profiling, which is the fastest-growing segment [37]. This growth is powered by the demand for high-resolution biomolecular analysis in the development of biologics and personalized medicine.

Quantitative Comparison: CE vs. HPLC

The following tables summarize key quantitative differences between CE and HPLC, providing a clear basis for instrument selection and cost-benefit analysis.

Table 1: Instrument Cost and Operational Comparison

| Aspect | Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument Cost (New Systems) | $5,000 - $150,000, depending on type and features [38]. Simple systems can be built from low-cost, open-source components [39]. | Typically higher than basic CE systems, though direct price comparisons are vendor-specific. |

| Consumables Cost | Lower buffer consumption (aqueous buffers), but capillaries and specific kits represent recurring costs [40]. | Higher solvent consumption (often acetonitrile), and column costs are significant recurring expenses [36]. |

| Sample Volume | Nanoliters (nL) [34]. | Microliters (µL) to milliliters (mL). |

| Solvent/Waste Generation | Very low (mL per day of aqueous buffer) [36] [34]. | High (liters per day of organic solvents) [36]. |

| Throughput | High (rapid separations, often minutes) [41]. | Moderate to High (can be slower than CE for some applications). |

Table 2: Analytical Performance and Practical Considerations

| Aspect | Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Mechanism | Electrophoretic mobility (charge/size ratio) in an electric field [41]. | Partitioning between stationary and mobile phases [34]. |

| Separation Efficiency | Very high (theoretical plates often > 100,000) [34]. | High (theoretical plates typically 10,000 - 20,000 for a modern column). |

| Primary Applications | Charged species, ions, proteins, DNA, chiral compounds, polar molecules [35] [42]. | A wide range of non-polar to polar molecules, depending on the mode. |