Beyond the Test Tube: Bridging the Gap Between In Vitro and Cellular Enzyme Kinetics in Crowded Environments

This article addresses the critical challenge of reconciling discrepancies in enzyme kinetic data obtained from simplified in vitro assays versus complex cellular environments.

Beyond the Test Tube: Bridging the Gap Between In Vitro and Cellular Enzyme Kinetics in Crowded Environments

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of reconciling discrepancies in enzyme kinetic data obtained from simplified in vitro assays versus complex cellular environments. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the profound effects of macromolecular crowding—a key feature of the intracellular milieu—on enzyme catalysis. We first establish the foundational principles of how crowding alters protein dynamics, stability, and conformational ensembles. The discussion then progresses to methodological approaches for mimicking cellular crowding in vitro and their application in drug discovery. The article provides a troubleshooting framework for optimizing biochemical assays to better predict cellular behavior and concludes with a comparative analysis of techniques for validating kinetic parameters in living cells. By synthesizing insights across these four intents, this work provides a comprehensive guide to obtaining more physiologically relevant enzyme kinetics, thereby enhancing the predictive power of in vitro data for therapeutic development.

The Crowded Cell: Fundamental Principles of Macromolecular Crowding and Enzyme Behavior

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between studying enzymes in dilute solution versus in a crowded cellular environment?

In dilute solutions, enzymes are studied in an idealized, non-physiological environment where water is the dominant component. In contrast, the interior of a cell is a highly crowded milieu, where macromolecules like proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides can occupy 20-40% of the total volume [1] [2] [3]. This macromolecular crowding profoundly alters the properties of the cellular environment, leading to:

- Reduced Diffusion Rates: The movement of enzymes and substrates is slowed down due to increased viscosity and obstructions [1] [2].

- Excluded Volume Effects: The physical space occupied by crowders reduces the available volume for other molecules, favoring more compact states and shifting reaction equilibria [1] [4] [3].

- Altered Protein Dynamics: Crowding can suppress large-scale conformational changes in enzymes and stabilize their structures, which directly impacts catalysis [1].

- Soft Interactions: Beyond simple volume exclusion, weak, non-specific chemical interactions (e.g., electrostatic, hydrophobic) with crowders can further modulate enzyme behavior [2] [4].

Q2: My enzyme's activity changes when I add crowders. Why does it sometimes increase and sometimes decrease?

The variable effects on activity arise because crowding influences multiple factors simultaneously, and the net outcome depends on which factor dominates for your specific enzyme and reaction. The table below summarizes the primary mechanisms.

Table: Mechanisms Behind Crowding-Induced Changes in Enzyme Activity

| Effect on Activity | Primary Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Increase | Excluded volume effect favors compact, active conformations and can enhance substrate binding affinity (lower Km). | Acetaldehyde reduction by yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (YADH) showed an increased Vmax with Ficoll and dextran crowders [4]. |

| Decrease | Increased viscosity slows diffusional encounter rates between enzyme and substrate, and can hinder product release. | Ethanol oxidation by YADH showed decreased Vmax and Km in the presence of Ficoll and dextran [4]. The tryptophan synthase α2β2 complex showed reduced rates of conformational transitions [1]. |

| Substrate-Selective Change | Combined effects of viscosity, excluded volume, and soft interactions that differentially affect hydrophobic vs. hydrophilic substrates. | α-Chymotrypsin activity was enhanced only for a hydrophobic substrate when mixed with functionalized gold nanoparticles, but not for other substrates [1]. |

Q3: How do I choose the right crowding agent for my in vitro experiments?

The choice of crowding agent depends on whether you aim to study a generic excluded volume effect or more physiologically relevant interactions. The key is to understand their properties, as detailed in the table below.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Mimicking Cellular Crowding

| Crowding Agent | Key Properties & Functions | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll | Synthetic polymer, inert, spherical shape. Often used to study excluded volume effects with minimal soft interactions [4]. | A common starting point for probing pure crowding effects. |

| Dextran | Branched polysaccharide. Used to study excluded volume and chemical interactions [4]. | Can form a depletion layer around the enzyme when larger than the protein, mitigating viscous effects [4]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Synthetic polymer, chemically inert, available in various molecular weights. Mimics molecules of different sizes [1] [3]. | Low molecular weight PEG can behave differently than high molecular weight PEG [1]. Can induce substrate-selective effects. |

| Proteins (e.g., BSA) | Physiologically relevant crowders. Introduce both excluded volume and a complex network of potential weak interactions [2]. | Most accurately mimics the intracellular environment but results are more complex to interpret. |

Q4: My kinetic data (Km and Vmax) is inconsistent under crowding conditions. What could be going wrong?

Inconsistent kinetic parameters are a common challenge that often stems from an interplay of factors not accounted for in the assay design.

- Viscosity Artifacts: High viscosity can make substrate diffusion rate-limiting, leading to an underestimation of Vmax. Ensure you are working in the linear range for your assay and consider using low molecular weight crowders or those that create a depletion layer to mitigate this [5] [4].

- Non-Ideal Mixing: With viscous crowding agents, ensure your reaction mixture is homogenized thoroughly to avoid concentration gradients.

- Crowder-Enzyme Interactions: The crowders may not be inert. "Soft interactions" can directly stabilize or destabilize the enzyme's active conformation, altering both Km and Vmax. Try replicating your experiment with a different type of crowder (e.g., switch from dextran to Ficoll) to probe for these interactions [4].

- Assay Linearity: Always verify that your assay operates in the linear range with respect to time and enzyme concentration, as crowding can shift this range [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Determining Whether a Change in Enzyme Activity is Due to Crowding or Viscosity

A change in observed activity can be caused by a genuine crowding effect (e.g., a shift in conformational equilibrium) or simply by the increased viscosity of the solution slowing diffusion. This protocol helps you distinguish between the two.

Diagram: Workflow for Distinguishing Crowding from Viscosity Effects

Experimental Protocol:

- Prepare Samples:

- Sample A (Baseline): Enzyme and substrate in your standard assay buffer.

- Sample B (Viscosity Control): Enzyme and substrate in buffer supplemented with an inert viscosity-increasing agent like glycerol or sucrose. The concentration should be adjusted to match the viscosity of your crowder solution. A viscometer is ideal for this, or you can use literature values.

- Sample C (Crowding Test): Enzyme and substrate in buffer containing your chosen crowding agent (e.g., 25 g/L Ficoll 70).

- Measure Initial Rates: Perform your enzyme activity assay under identical conditions (temperature, pH, substrate concentration) for all three samples. Ensure the measurements are taken in the linear range [5].

- Analyze Data:

- If the activity in Sample B (viscosity control) is similar to Sample C (crowder), the effect is likely due to macroscopic viscosity.

- If the activity in Sample C is significantly different (higher or lower) than in Sample B, it indicates a specific crowding effect beyond simple viscous slowing, such as excluded volume or soft interactions [4].

Issue: Optimizing an Enzyme Assay for Crowded Conditions

Traditional, one-factor-at-a-time optimization can be time-consuming. This guide uses a systematic approach to efficiently find optimal assay conditions.

Experimental Protocol: A Design of Experiments (DoE) Approach The following steps, adapted for crowding research, can significantly speed up assay optimization [6].

- Define Your Objective: Clearly state what you want to optimize (e.g., maximize initial reaction rate, or signal-to-noise ratio).

- Identify Key Factors: Select the variables you will test. For a crowding assay, critical factors often include:

- Crowder Concentration (e.g., 0, 50, 100 g/L)

- Substrate Concentration (relative to Km)

- Enzyme Concentration

- pH

- Type of Crowder (this is a categorical factor)

- Run a Fractional Factorial Design: This screening design allows you to test multiple factors simultaneously with a minimal number of experiments to identify which factors have the most significant impact on your objective.

- Perform Response Surface Methodology (RSM): Once the key factors are identified, use a RSM design (e.g., Central Composite Design) to model the relationship between these factors and your response. This will help you find the optimal levels for each factor.

- Verify the Model: Run a confirmation experiment using the predicted optimal conditions to validate the model's accuracy.

Key Quantitative Data in Crowding Research

The following table consolidates experimental findings from various studies to illustrate how crowding diversely affects different enzymes.

Table: Compiled Kinetic Parameters of Enzymes Under Macromolecular Crowding Conditions

| Enzyme | Crowding Agent | Observed Change in Kinetics | Postulated Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Alcohol Dehydrogenase (YADH) [4] | Ficoll, Dextran | Ethanol Oxidation: Vmax ↓, Km ↓Acetaldehyde Reduction: Vmax ↑, Km ↑ | Direction-dependent balance of excluded volume (favors compact state) vs. viscosity (hinders diffusion/product release). |

| α-Chymotrypsin [1] | PEG Conjugation / Dextran | Catalytic rate (kcat) ↓, Km ↑ | Reduced structural dynamics and conformational flexibility; slower diffusion. |

| α-Chymotrypsin [1] | Gold Nanoparticles (AuTEG) | Activity ↑ for hydrophobic substrate only | Substrate-selective enhancement due to combined crowding and chemical interactions. |

| Multi-copper Oxidase (Fet3p) [1] | Not Specified | Low Crowding: Km ↑, Kcat ↑High Crowding: Km ↓, Kcat ↓ | Complex, concentration-dependent interplay of multiple factors. |

| G-Quadruplex (G4) DNA Stability [3] | PEG 200 | Melting Temperature (Tm) ↑ from 68.4°C to >80°C | Excluded volume effect strongly stabilizes compact nucleic acid structures. |

The intracellular environment is a densely packed milieu, with biological macromolecules occupying 5%–40% of cellular volume and reaching total concentrations of 80 to 400 mg/mL [7]. This creates a unique crowded medium that differs significantly from the ideal, dilute conditions typically used in in vitro biochemical assays [7]. Understanding how this crowded environment affects enzyme kinetics is crucial for extrapolating in vitro findings to in vivo conditions.

This technical support center addresses the core mechanisms through which crowding operates: excluded volume effects, soft interactions, and depletion layers. The following sections provide troubleshooting guidance and methodological support for researchers investigating these phenomena in enzyme kinetics.

Core Mechanisms & Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my enzyme's activity affected differently by various crowding agents, even when they have similar molecular weights?

Issue: Different crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll vs. Dextran) of similar molecular weight produce divergent effects on kinetic parameters.

Explanation: This occurs because the impact of crowding extends beyond simple excluded volume effects. The overall effect is a sum of multiple factors [7] [8] [9]:

- Excluded Volume Effect: Tends to increase thermodynamic activity and can favor compact states, potentially increasing reaction rates [7].

- Viscosity and Perturbed Diffusion: High viscosity from crowding agents can slow molecular diffusion, counteracting excluded volume effects and reducing reaction rates, particularly for diffusion-limited enzymes [7] [8].

- Soft Interactions: Non-specific, weak chemical interactions (e.g., repulsive or attractive forces) between the crowder and your enzyme can alter stability and conformation [7] [9]. Repulsive interactions can mimic excluded volume, while attractive interactions can oppose them.

- Depletion Layer Effects: In solutions containing crowders significantly larger than the enzyme, a depletion layer can form around the enzyme, locally reducing viscosity and diminishing the hindrance to diffusion [8].

Solution:

- Characterize both the thermodynamic and viscous properties of your crowding solutions.

- Use multiple, structurally different crowding agents to disentangle steric effects from chemical interactions.

- For suspected depletion layer effects, use crowders of varying sizes relative to your enzyme.

FAQ 2: Why do I observe a decrease in catalytic rate (kcat) despite predictions that crowding should accelerate my reaction?

Issue: Observed reaction rates decrease under crowded conditions, contrary to theoretical predictions based solely on excluded volume.

Explanation: This is a common finding, as seen with Mycobacterium tuberculosis InhA, where some crowders showed negligible or negative effects on activity [9]. Potential causes include:

- Viscosity Dominance: For reactions where product release or a conformational change is rate-limiting, increased microviscosity can slow this step more than excluded volume accelerates the binding or chemical step [8].

- Unfavorable Transition State Stabilization: If the enzyme's transition state is more expanded than the ground state, crowding can paradoxically destabilize it, increasing the activation energy [9].

- Non-Specific "Soft" Interactions: Attractive interactions between the crowder and the enzyme can lead to a more compact, less active conformer or cause minor unfolding, as suggested by molecular dynamics simulations in sucrose solutions [9].

Solution:

- Determine the rate-limiting step of your enzyme's catalytic cycle.

- Perform Arrhenius analysis to investigate changes in the activation energy; non-linear plots can indicate significant "soft" interactions [9].

- Use techniques like circular dichroism or fluorescence spectroscopy to probe for crowding-induced conformational changes.

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally distinguish the contribution of excluded volume from other crowding mechanisms?

Issue: Difficulty in attributing observed kinetic changes specifically to excluded volume.

Explanation: Pure excluded volume effects are thermodynamic in nature, while the observed kinetics are an amalgam of thermodynamic and dynamic (viscous) factors.

Solution:

- Use Inert, Spherical Crowders: Ficoll is often preferred over dextran or PEG for initial studies as it is more globular and exhibits fewer chemical interactions [9].

- Compare Small Molecules vs. Polymers: Use a small molecule osmolytes (e.g., glucose) versus a polymeric crowder (e.g., dextran) at the same mass concentration. Glucose will contribute to osmotic pressure but has a much smaller excluded volume effect, helping to isolate the steric component [8] [9].

- Analyze Activation Parameters: Determine the Gibbs free energy of activation (ΔG‡). If excluded volume is the dominant factor, you would expect a significant change in ΔG‡. Similar ΔG‡ values between crowded and non-crowded conditions, as found for InhA, suggest that excluded volume effects are not facilitating the formation of the activated complex [9].

Table 1: Interpreting Crowding Effects on Kinetic Parameters

| Observation | Possible Mechanism | Experimental Verification |

|---|---|---|

↑ kcat, ↓ or Km |

Dominant excluded volume effect favoring transition state | Measure thermodynamic activity; use inert crowders like Ficoll [8]. |

↓ kcat, ↑ Km |

Dominant viscosity hindering diffusion or conformational changes | Measure microviscosity; use crowders of different intrinsic viscosity [7] [8]. |

↓ kcat / Km, unchanged ΔG‡ |

Significant "soft" interactions altering enzyme conformation | Perform Arrhenius analysis; use spectroscopic methods to check structure [9]. |

| Disparate effects from crowders of similar size | Specific chemical (soft) interactions with crowder | Use a panel of chemically distinct crowders (e.g., Ficoll, dextran, PEG) [8]. |

Experimental Protocols

General Protocol for Assessing Crowding Effects on Enzyme Kinetics

This protocol is adapted from studies on alcohol dehydrogenase and InhA [8] [9].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of your chosen crowding agent (e.g., 300-400 g/L) in assay buffer.

- Clarify solutions by filtration or centrifugation if necessary.

- Confirm that the crowder does not absorb at wavelengths used for detection.

2. Initial Velocity Measurements:

- Prepare assay mixtures containing a fixed, saturating concentration of one substrate and varying concentrations of the other substrate.

- Include crowding agent across a concentration range (e.g., 0, 50, 100, 200 g/L).

- Pre-incubate all reaction components except the enzyme at the desired temperature.

- Initiate reactions by adding enzyme. For very viscous solutions, ensure thorough mixing.

- Monitor product formation continuously (preferred) or use fixed time points.

3. Data Analysis:

- Fit initial velocity (

v) vs. substrate concentration ([S]) data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v = (Vmax * [S]) / (Km + [S])) or the Hill equation for non-hyperbolic kinetics [9]. - Plot derived parameters (

Km,kcat,kcat/Km) against crowder concentration to identify trends.

Advanced Protocol: Determining Activation Parameters

To gain deeper insight into the crowding mechanism, perform the above experiment at multiple temperatures (e.g., 15, 20, 25, 30 °C) and construct an Arrhenius plot [9].

1. Data Collection:

- Determine

kcatat a minimum of four different temperatures for both crowded and non-crowded conditions.

2. Analysis:

- Construct an Arrhenius plot by plotting

ln(kcat)against1/T(where T is temperature in Kelvin). - The slope of the linear fit is

-Ea/R, whereEais the activation energy and R is the gas constant. - Calculate the activation enthalpy (ΔH‡) and entropy (ΔS‡) using the Eyring equation.

- The Gibbs free energy of activation (ΔG‡) is calculated as ΔG‡ = ΔH‡ - TΔS‡.

- Compare these activation parameters between crowded and non-crowded conditions. A change in ΔG‡ suggests a thermodynamic effect (e.g., excluded volume), while a non-linear Arrhenius plot indicates complex behavior, potentially from "soft" interactions [9].

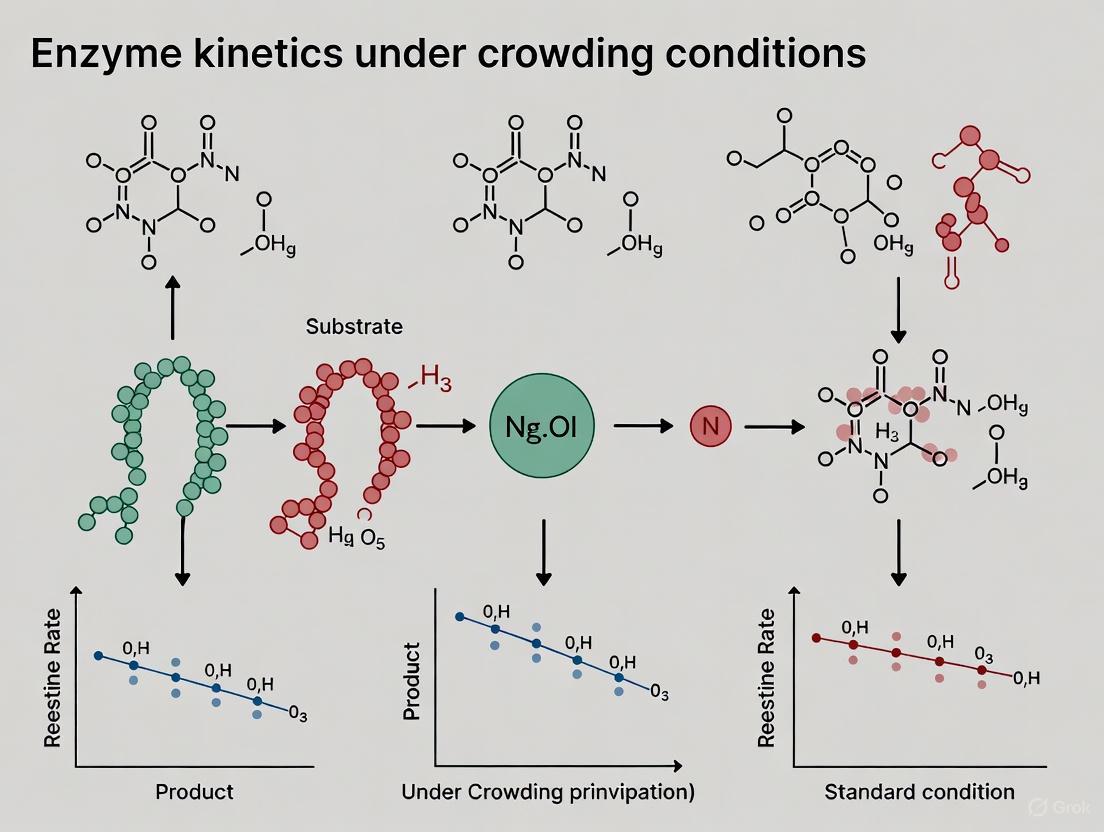

Visualizing the Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms through which macromolecular crowding agents influence enzyme kinetics, integrating excluded volume, soft interactions, viscosity, and depletion layers.

Diagram 1: Crowding mechanisms influencing enzyme kinetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Common Reagents for Crowding Studies

| Reagent | Typical MW Range | Key Properties & Uses | Considerations & Potential Artifacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ficoll | 70 - 400 kDa | Synthetic copolymer of sucrose and epichlorohydrin. Globular, highly hydrophilic. Often used as an "inert" crowder to model excluded volume with minimal soft interactions [8] [9]. | Solutions have lower viscosity than linear polymers of similar MW. Ficoll 400 may show mild attractive interactions with some proteins [9]. |

| Dextran | 40 - 2000 kDa | Branched polysaccharide of glucose. Linear and flexible polymer. Used to study effects of polymer flexibility and size on crowding [8]. | Can exhibit significant viscosity. May form depletion layers when much larger than the test protein, reducing local viscosity [8]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | 1 - 20 kDa | Linear, flexible polymer. Very commonly used. Can induce macromolecule condensation and phase separation [9]. | Hydrophobic character can lead to significant attractive soft interactions with protein surfaces, potentially causing aggregation or conformational changes [9]. |

| Sucrose | 342 Da | Disaccharide. Used as a small molecule control and to study osmotic effects vs. polymeric crowding. Also a natural cryoprotectant [10]. | Contributes little to excluded volume but can alter water activity and stabilize proteins via preferential hydration. Can induce compact conformations [9]. |

| Glucose | 180 Da | Monosaccharide. Used as a negative control for polymeric crowders, as it has minimal excluded volume effect [9]. | Primarily alters osmotic pressure. Useful for isolating the steric component of larger polymers by comparison [9]. |

The table below summarizes real experimental findings from the literature to illustrate how different crowding mechanisms manifest in practice.

Table 3: Experimental Observations of Crowding Mechanisms in Enzyme Kinetics

| Enzyme | Crowding Agent | Observed Effect on Kinetics | Proposed Dominant Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Alcohol Dehydrogenase (YADH) - Ethanol Oxidation [8] | Ficoll, Dextran | ↓ Vmax, ↓ Km |

Viscosity hindering product release (NAD+) counteracting some excluded volume effects on substrate binding. |

| Yeast Alcohol Dehydrogenase (YADH) - Acetaldehyde Reduction [8] | Ficoll, Dextran | or ↑ Vmax |

Excluded volume effect favoring the reaction (possibly more compact transition state), partially counteracted by viscosity. |

| M. tuberculosis InhA [9] | Ficoll 70, Ficoll 400, Dextran 70 | Negligible effects on Km, kcat, and kcat/Km |

A balance of opposing factors (excluded volume, viscosity, soft interactions), with no net dominance of excluded volume. |

| M. tuberculosis InhA [9] | PEG 6000 | Complex effects, non-linear Arrhenius plot | Significant "soft" interactions between PEG and the enzyme, introducing an enthalpic component. |

| M. tuberculosis InhA [9] | Sucrose | Decreased kcat/Km for NADH and kcat for DD-CoA |

"Soft" interactions leading to a more compact, less active enzyme conformation, as suggested by MD simulations. |

Enzyme kinetics under cellular-like crowding conditions often deviate from results obtained in dilute, ideal solutions. This discrepancy arises because crowding fundamentally alters protein dynamics, conformational ensembles, and stability [11] [12]. In confined and crowded environments, enzymes operate within a complex thermodynamic and kinetic landscape, where excluded volume effects, anomalous diffusion, and altered solvation can modulate function [11]. A comprehensive understanding requires shifting from viewing proteins as static structures to analyzing them as dynamic ensembles interconverting between multiple conformations [13] [12]. This technical guide addresses the specific experimental issues and solutions for characterizing protein dynamics and allosteric regulation under these non-ideal conditions.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why do my measured enzyme kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) change significantly under molecular crowding conditions?

Answer: Changes in observed kinetics are frequently due to the altered thermodynamic and dynamic environment, not just a simple change in enzyme activity.

- Molecular Crowding and Excluded Volume: Crowding agents reduce the available volume, which can stabilize more compact conformations and shift the conformational ensemble of the protein. This shift can affect substrate binding (apparent Km) and the rates of conformational changes necessary for catalysis (apparent kcat) [11] [12].

- Modulation of Protein Dynamics: Allosteric regulation is mediated not only by conformational shifts but also by changes in the dynamics and fluctuations of the protein on timescales from picoseconds to milliseconds [13]. Crowding can dampen or enhance these dynamics, thereby affecting the reaction coordinate and the enzyme's catalytic efficiency [14].

- Altered Cofactor Dynamics: For cofactor-dependent enzymes, crowding can affect the local concentration, diffusion, and binding equilibrium of cofactors within the confined space, directly impacting the apparent reaction rate [11].

Solution: Move beyond bulk measurements. Employ techniques like time-lapse fluorescence microscopy at the single-particle level to measure intraparticle kinetics and cofactor diffusion directly within the crowded environment [11].

FAQ 2: My NMR spectra show significant line broadening under crowding conditions. How can I distinguish between true allosteric regulation and non-specific effects?

Answer: Line broadening can indicate altered dynamics or heterogeneous interactions. Disentangling these causes is key.

- Specific Allosteric Regulation: Involves defined communication pathways between allosteric and active sites, often mediated by networks of residues showing correlated changes in dynamics or conformation [13]. This typically results in specific, residue-specific changes in NMR parameters (e.g., chemical shifts, relaxation rates).

- Non-Specific Quinary Interactions: Crowding can lead to weak, transient "quinary interactions" with other macromolecules, causing non-specific broadening across many residues due to increased viscosity or heterogeneous complex formation [12].

Solution: Perform a residue-by-residue analysis.

- Compare Dynamics: Measure NMR relaxation parameters (R₁, R₂, NOE) under both dilute and crowded conditions. Residues involved in specific allosteric pathways will show targeted changes in picosecond-nanosecond or microsecond-millisecond dynamics, while non-specific interactions cause widespread dynamic perturbations [13] [12].

- Utilize Integrative Structural Biology: Correlate NMR data with other techniques. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can identify potential communication pathways and residue correlations [13] [12]. Techniques like cryo-EM can provide structural insights into populated conformational states within the ensemble [12].

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally validate if a proposed allosteric pathway is functional and relevant under crowding?

Answer: Validating allosteric pathways requires a combination of computational prediction and experimental mutational analysis.

- Computational Identification: Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to identify networks of residues with correlated motions or to calculate communication pathways based on protein structure [13].

- Experimental Mutational Analysis: Introduce point mutations at key residues identified in the proposed pathway.

- Functional Assays: Measure the impact of mutations on allosteric regulation under crowding conditions. A functional residue will show a significant change in the allosteric response (e.g., a change in substrate binding affinity or catalytic efficiency upon effector binding) without completely disrupting the native fold [13].

- Dynamic Characterization: Use NMR spectroscopy to confirm that the mutation perturbs the dynamic network, for example, by altering microsecond-millisecond conformational exchange dynamics detected through CPMG or R₁ρ relaxation dispersion experiments [13].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irreproducible kinetics in crowded systems | Particle-to-particle heterogeneity in enzyme density and distribution [11] | Perform single-particle or intraparticle kinetic analysis using fluorescence microscopy [11] |

| Loss of allosteric effect | Crowding alters the conformational equilibrium or quenches essential dynamics [13] [12] | Use NMR to probe if the effector still induces changes in dynamics and the conformational ensemble [13] |

| Uncertain transition pathway | Debate between induced-fit vs. conformational selection mechanisms [13] | Vary effector concentration; induced-fit becomes dominant at high concentrations [13]. Use TROSY-based NMR to detect minor populations. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Time-Lapse Fluorescence Microscopy for Intraparticle Kinetics

Objective: To measure apparent Michaelis-Menten parameters and cofactor diffusion within a single porous particle under operando conditions [11].

- Sample Preparation:

- Data Acquisition:

- Place the biocatalyst particles in a flow cell or on a microscope slide with the reactant solution.

- Use a fluorescence microscope with a temperature-controlled stage.

- For kinetic assays, record time-lapse images of individual particles upon introduction of substrate. The fluorescence change of the cofactor (e.g., NADH to NAD⁺) reports on the reaction progress [11].

- For diffusion studies, perform Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) by bleaching a spot on a particle and monitoring fluorescence recovery over time [11].

- Image Analysis and Kinetics:

- Process images to extract fluorescence intensity over time for individual particles.

- Plot initial reaction rates (V₀) against substrate concentration for each particle.

- Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten model (V₀ = (Vₘₐₓ * [S]) / (Kₘ + [S])) to determine the apparent Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ for that specific particle and its local crowded environment [11].

Protocol 2: NMR Relaxation Measurements to Probe Dynamics

Objective: To characterize protein backbone and side-chain dynamics on picosecond-nanosecond and microsecond-millisecond timescales [13].

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare ¹⁵N- or ¹³C/¹⁵N-labeled protein in a buffer compatible with crowding agents (e.g., synthetic polymers, sugars, or high concentrations of inert proteins like BSA).

- For studies of allostery, prepare samples: (a) apo, (b) with allosteric effector bound, (c) with substrate bound, and (d) with both.

- Data Acquisition:

- Picosecond-Nanosecond Dynamics: Perform ¹⁵N T₁, T₂, and heteronuclear {¹H}-¹⁵N NOE experiments. Model-free analysis of this data provides order parameters (S²) and effective correlation times, reporting on fast local motions [13].

- Microsecond-Millisecond Dynamics: Perform CPMG (Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill) relaxation dispersion experiments (R₂). A dispersion profile indicates conformational exchange processes on this timescale, and fitting the data can provide the kinetics (kₑₓ) and thermodynamics (populations) of the exchange, as well as the chemical shift difference between states [13].

- Data Interpretation:

- Map residues with significant changes in dynamics (S² or R₂) upon ligand binding onto the protein structure.

- A pathway of dynamically perturbed residues connecting the allosteric and active sites suggests a potential communication network [13].

Protocol 3: Transition Path Sampling (TPS) Simulations

Objective: To rigorously determine the reaction coordinate and atomic-level mechanism of a chemical step in an enzyme, including the role of promoting vibrations [14].

- System Setup:

- Build a simulation system with the enzyme in a solvated box, applying periodic boundary conditions.

- Use a QM/MM potential, treating the reacting atoms with quantum mechanics and the protein environment with molecular mechanics.

- Harvesting Reactive Trajectories:

- Use the TPS methodology to perform a Monte Carlo walk in trajectory space, generating an ensemble of true reactive trajectories that connect the reactant and product states without being trapped in intermediate minima [14].

- Identifying the Reaction Coordinate:

- Calculate the stochastic separatrix (the transition state ensemble).

- Use machine learning methods like kernel PCA on the separatrix to identify the minimal set of atomic coordinates (degrees of freedom) that are invariant on the separatrix. These constitute the reaction coordinate [14].

- Test the identified reaction coordinate using a committor analysis to ensure it accurately describes the progression of the reaction [14].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| His-tagged Enzymes | Enables oriented, site-specific immobilization on functionalized solid supports for heterogeneous biocatalysis studies [11]. | Ensures uniform attachment and controlled density on carrier surfaces. |

| Cationic Polymers (PEI, PAH) | Coating for carriers to enable reversible adsorption and confinement of phosphorylated cofactors (NADH, FAD, PLP) [11]. | Different polymer structures (primary, secondary, tertiary amines) influence cofactor binding affinity and capacity [11]. |

| Porous Agarose Microbeads | Common solid support for enzyme immobilization, providing a confined, crowd-like environment with defined porosity [11]. | Porosity controls intraparticle diffusion and the effective concentration of enzymes and cofactors. |

| Isotope-Labeled Proteins (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Essential for NMR spectroscopy studies to assign resonances and measure site-specific dynamics via relaxation experiments [13] [12]. | Required for probing dynamics and allostery at atomic resolution. |

| Synthetic Crowding Agents (Ficoll, PEG) | Mimic the excluded volume effect of the cellular interior in in vitro experiments [11] [12]. | Inert polymers are preferred to avoid specific interactions that complicate interpretation. |

| Transition Path Sampling (TPS) | A computational rare-event simulation methodology to uncover the true reaction coordinate and mechanism of enzymatic catalysis [14]. | Identifies promoting vibrations and key dynamic contributions to catalysis beyond static structures. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Issues in Crowding Studies

FAQ 1: Why does my enzyme show no change, or an unexpected change, in activity in crowded conditions?

This is a frequent observation, as crowding effects are highly system-dependent. The activity can increase, decrease, or remain unchanged based on the enzyme's specific properties and the experimental setup.

- Probable Cause 1: Incompatibility between crowder and enzyme. Non-specific (soft) chemical interactions between the crowding agent and your enzyme or substrate can override the expected excluded volume effects.

- Solution: If you observe no effect or an unexpected effect with one crowder, try a different type. For instance, switch from a linear polymer like PEG or dextran to a more globular one like Ficoll, or use a protein-based crowder like BSA. The effects can be starkly different; for example, Ficoll was shown to enhance the activity of adenylate kinase, while dextrans had a lesser effect [15].

- Probable Cause 2: Substrate-dependent effects. The nature of the substrate can dictate how crowding influences enzyme kinetics.

- Solution: Test your enzyme with multiple substrates. A study on α-chymotrypsin found that large, hydrophobic substrates showed a marked increase in activity with certain crowders, while the hydrolysis of smaller substrates was unaffected [1].

FAQ 2: Why are my kinetic data in crowded conditions inconsistent or not fitting the Michaelis-Menten model?

Crowding can alter multiple aspects of the reaction environment, leading to complex kinetics that deviate from standard models.

- Probable Cause 1: Slowed diffusion and transient trapping. The diffusion of the enzyme and substrate is significantly hindered in a crowded milieu. Substrates can be transiently trapped by crowders, leading to fractal-like kinetics where the law of mass action breaks down [16].

- Solution: Consider extending incubation times to ensure reactions reach completion. For data analysis, models that account for diffusion limitations may be more appropriate than classic Michaelis-Menten analysis in highly crowded conditions.

- Probable Cause 2: Conformational selection is biased. Crowding can shift the equilibrium of an enzyme's conformational ensemble. If crowding stabilizes a less active conformation, it can lead to a reduction in the maximum velocity (Vmax).

- Solution: Monitor enzyme conformation using techniques like circular dichroism (CD) or fluorescence spectroscopy alongside activity assays. For HIV-1 protease, crowding agents suppress the opening of the flexible flaps, a conformation necessary for substrate binding, thereby reducing activity [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols for Key Crowding Studies

Protocol: Measuring the Effect of Crowding on HIV-1 Protease Kinetics

This protocol is adapted from fluorescence-based assays used to study HIV-1 protease [17].

Objective: To determine the kinetic parameters (KM and Vmax) of HIV-1 protease under non-crowded and crowded conditions.

Materials:

- Enzyme: HIV-1 PR (commercially available).

- Substrate: A FRET-based peptide substrate (e.g., Arg-Glu(EDANS)-Ser-Gln-Asn-Tyr-Pro-Ile-Val-Gln-Lys(DABCYL)-Arg). Cleavage separates the EDANS donor and DABCYL acceptor, increasing fluorescence.

- Crowding Agents: Polyethylene glycol (PEG) of varying molecular weights (e.g., PEG 600 and PEG 6000).

- Buffer: 100 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.7, containing 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 g/L BSA.

- Equipment: Fluorescence plate reader capable of excitation at 340 nm and emission detection at 490 nm.

Method:

- Stock Solutions: Prepare stock solutions of the crowding agents (e.g., 100, 200, and 300 g/L) in the assay buffer.

- Substrate Dilution: Serially dilute the FRET substrate in DMSO and then in assay buffer (with or without crowders) to achieve final concentrations between 15-120 µM in the reaction well. Keep the final DMSO concentration consistent (e.g., 15%).

- Reaction Setup: In a 100 µL reaction volume, combine the substrate solution and crowding agent/buffer. Initiate the reaction by adding HIV-1 PR to a final concentration of 4.4 nM.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately transfer the plate to the pre-heated reader (37°C) and record the fluorescence every 30 seconds for 30 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Convert fluorescence readings to product concentration using an EDANS standard curve. Plot the initial velocity (v0) against substrate concentration ([S]) and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to extract KM and Vmax.

Protocol: Assessing α-Chymotrypsin Activity and Stability under Crowding

This protocol synthesizes methodologies from multiple studies on α-chymotrypsin and its zymogen [1] [19].

Objective: To evaluate the effect of macromolecular crowding on the catalytic efficiency and structural stability of α-chymotrypsin.

Materials:

- Enzyme: α-Chymotrypsin.

- Substrates: A range of substrates, including N-succinyl-l-phenylalanine-p-nitroanilide (SPNA) and the more hydrophobic N-succinyl-alanine-alanine-proline-phenylalanine-p-nitroanilide (TP).

- Crowding Agents: Dextran 70 and PEG of varying molecular weights.

- Buffer: Appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris or phosphate buffer at neutral pH).

- Equipment: Spectrophotometer, fluorometer, and circular dichroism (CD) spectropolarimeter.

Method:

- Activity Assay:

- Prepare solutions with and without crowders (e.g., Dextran 70 at 0-300 g/L).

- For each condition, mix enzyme with different substrates and monitor the release of the chromogenic product (p-nitroaniline) spectrophotometrically at 410 nm.

- Calculate kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) as in the HIV-1 protease protocol.

- Thermal Stability Assay:

- Prepare enzyme samples in crowded and non-crowded buffers.

- Use a temperature-controlled spectrophotometer or fluorometer to monitor the loss of native structure (e.g., via increased turbidity or intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence) as the temperature is increased.

- Determine the melting temperature (Tm) for each condition. Crowding is expected to increase Tm, indicating stabilization [19].

- Conformational Analysis (Optional):

- Use Far-UV CD spectroscopy to monitor changes in the secondary structure of the enzyme in the presence of crowders. Crowding agents like dextran can stabilize the native structure against denaturants [19].

Data Presentation: Comparative Kinetic Effects of Crowding

| Enzyme | Crowding Agent | Observed Effect on KM | Observed Effect on kcat / Vmax | Proposed Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Chymotrypsin [1] | Dextran 70 | Increases | Decreases | Slowed diffusion; stabilization of a less active, open conformation. |

| α-Chymotrypsin [1] | PEG (Low MW) | Increases | Decreases | Increased substrate affinity but decreased turnover; coupled hydration/solvation effects. |

| α-Chymotrypsin [1] | Gold Nanoparticles (AuTEG) | Substrate-dependent (decreased for hydrophobic sub.) | Substrate-dependent (increased for hydrophobic sub.) | Selective enhancement of hydrophobic substrate binding and catalysis. |

| HIV-1 Protease [17] [18] | PEG 600 / PEG 6000 | Increases | Decreases | Suppression of flap opening dynamics; reduced enzyme-substrate diffusional encounter rates. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Crowding Studies

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | A synthetic, highly branched, globular polysaccharide crowder. | Often considered relatively inert; useful for studying pure excluded volume effects. Can enhance enzyme activity (e.g., in adenylate kinase) [15]. |

| Dextran | A linear, flexible polymer of glucose used as a crowder. | Available in various molecular weights. Effects can be concentration and size-dependent; can slow reactions by increasing viscosity and residence times [16]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A linear, flexible polymer commonly used as a crowder. | Can have significant chemical interactions with proteins, beyond excluded volume. Often suppresses enzyme activity by stabilizing less dynamic conformations [17] [20]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein-based crowding agent. | Provides a more biologically relevant crowder but introduces potential for specific and non-specific interactions, complicating data interpretation [21]. |

| FRET-based Peptide Substrates | Sensitive substrates for continuous monitoring of protease activity. | Essential for studying kinetics without interference from crowded media. The FRET signal is typically insensitive to the presence of inert crowders [17]. |

Conceptual Workflow: Analyzing Enzyme Response to Crowding

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for diagnosing how crowding affects an enzyme, based on the case studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental theoretical framework for understanding enzyme behavior in crowded environments? The energy landscape model is the key framework for understanding how macromolecular crowding influences enzymes. This model visualizes protein folding and function as a journey across a topographic map, where stable states correspond to energy minima. Crowding agents, which can occupy 20-40% of cellular volume, perturb this landscape through two primary mechanisms [1] [22]:

- Excluded Volume Effects: Crowders reduce the volume available to a protein, entropically favoring more compact native states over expanded unfolded states. This typically stabilizes the protein and increases its thermodynamic stability.

- Soft Interactions: Beyond simple steric effects, chemical interactions (e.g., electrostatic, hydrophobic) between the protein and crowders can also alter the energy landscape, sometimes leading to destabilization or aggregation [22].

In practice, crowding remodels the energy landscape by stabilizing the native state and, crucially, by compacting the unfolded state ensemble. This compaction can be detected experimentally by a decrease in the m-value (the dependence of unfolding free energy on denaturant concentration) [23]. Furthermore, crowding can alter the kinetic barriers between states, leading to observed changes in folding/unfolding rates and conformational switching [22] [24].

FAQ 2: Why do I observe unpredictable changes in enzyme kinetics under crowding conditions?

Catalytic rates (k_cat) and substrate binding (K_m) can increase, decrease, or remain unchanged because crowding's net effect results from a balance of multiple, competing factors [1]:

- Stabilization vs. Rigidification: While excluded volume stabilizes the native fold, it can also restrict the conformational dynamics essential for catalytic activity. This often manifests as an increase in thermal stability coupled with a decrease in the turnover number [1].

- Diffusion vs. Association: Crowding slows translational and rotational diffusion, which can slow substrate encounter rates. Conversely, the excluded volume effect also increases the effective concentration of reactants, favoring complex formation [25]. The dominant effect depends on the specific system and reaction.

- Altered Energy Landscapes: For complex enzymes like metamorphic proteins (e.g., KaiB, XCL1) or allosteric enzymes, crowding can selectively stabilize one functional conformation over another, thereby shifting the population equilibrium and modulating activity and specificity [1] [22].

FAQ 3: How does crowding affect the function of enzymes that switch between distinct folds? Research on metamorphic proteins shows that crowding agents shift the conformational equilibrium toward the more compact, typically inactive state. However, the effect on the switching rate is timescale-dependent [22]:

- For fast-switching proteins (e.g., XCL1, timescale of seconds), crowding can significantly slow the interconversion rate (

k_ex), as observed with PEG which reduced the rate by ~57% [22]. - For slow-switching proteins (e.g., KaiB, timescale of hours), crowding has a minimal effect on the interconversion rate but still shifts the population equilibrium [22]. This indicates that crowding acts as a tuner of both the thermodynamics and kinetics of fold-switching, which can be critical for regulating biological function in vivo.

FAQ 4: My enzyme is aggregating in crowded solutions. What is happening? Crowding can significantly increase the propensity for aggregation and misfolding [23]. The excluded volume effect not only stabilizes the native state but also stabilizes any compact state, including misfolded oligomers or aggregates. This is a major complication in experimental studies of crowding. Mitigation strategies include:

- Using inert crowding agents like Ficoll or dextran, which minimize soft, attractive interactions.

- Systematically varying the type and concentration of the crowding agent to identify conditions that favor native structure.

- Ensuring your protein is pure and monodisperse before adding crowders.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Crowding Effects on Enzyme Activity

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Size & Nature | Compare kinetics with substrates of different sizes and hydrophobicity. | Use a range of substrate sizes. Interpret results considering that crowding effects can be substrate-selective [1]. |

| Crowder Properties | Test different types of crowders (e.g., Ficoll 70 vs. Dextran 70) at the same weight/volume concentration. | Characterize crowding effects with multiple, well-defined agents. Ficoll is a compact sphere; Dextran is a flexible coil; PEG can have chemical interactions [24]. |

| Conformation-Specific Effects | Use techniques like NMR or fluorescence spectroscopy to probe conformational dynamics, not just overall structure. | Interpret kinetic data in the context of conformational ensembles. Crowding may stabilize a specific, less active conformation [1]. |

Issue 2: Measuring Stability and Unfolding in Crowded Environments

Challenge: Standard denaturation experiments (e.g., urea titrations) are complicated by crowding, as the crowder itself excludes denaturant and affects its local concentration.

Protocol: Equilibrium Urea Denaturation in Ficoll 70 [23]

- Preparation: Create a series of urea stock solutions (in desired buffer) with identical concentrations of Ficoll 70. Include a reductant like TCEP if needed.

- Sample Equilibration: Mix protein stock (in the same Ficoll/buffer) with the urea/Ficoll stocks to a final protein concentration of 0.8–6.4 µM. Ensure all samples have the same Ficoll concentration.

- Incubation: Equilibrate samples for a sufficiently long time (e.g., >5.5 hours at 37°C) in a sealed, temperature-controlled incubator to prevent evaporation.

- Measurement: Monitor unfolding by intrinsic fluorescence (e.g., emission at 350 nm with excitation at 280 nm) or far-UV Circular Dichroism (CD). Centrifuge samples before measurement to remove any aggregates.

- Data Analysis: Fit the data to a two-state unfolding model. A key diagnostic parameter is the

m-value. A decrease in them-valueunder crowding indicates compaction of the denatured state ensemble [23].

Issue 3: Quantifying Altered Energy Landscapes and Binding

Challenge: Crowding reduces the size of the intermolecular energy funnel, making it harder for binding partners to find each other [26].

Protocol: Assessing the Binding Funnel Size via Docking Simulations [26]

- System Setup: Use a coarse-grained docking program (e.g., GRAMM) to generate a large number (~1000) of low-energy docking poses for a protein complex in a dilute environment.

- Introduce Crowders: Generate multiple random distributions of spherical crowders within the simulation volume, with a volume fraction matching your experimental conditions.

- Clash Detection: For each crowder distribution, count the number of docking poses that do not sterically clash with the crowders (

N_tot_nc). - Identify Functional Poses: Count the number of these clash-free poses that are located in the known biological binding site (

N_bs_nc). - Calculate Funnel Size: The binding site ratio

η = (Σ N_bs_nc) / (Σ N_tot_nc)quantifies the effective size of the energy funnel. This ratioηdecreases as crowder concentration increases, directly showing how crowding restricts productive binding [26].

Table 1: Experimental Effects of Crowding on Model Systems

| Protein | Crowding Agent | Effect on Stability | Effect on Kinetics / Function | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRABP I (β-rich protein) [23] | Ficoll 70 | Modest stability increase (ΔΔG° ≤ ~1.2 kcal/mol) | Retarded unfolding; No change in transition state. | Crowding compacts the unfolded state, decreasing the m-value. |

| α-Chymotrypsin [1] | Dextran 70 / PEG | Stabilization | Decreased vmax, Increased Km | Crowding can restrict essential conformational dynamics, reducing activity. |

| LDH in BSA-PEG Droplets [27] | Protein Droplets (~430 mg/mL BSA) | N/A | Increased kcat; Unchanged Km | Extreme crowding and compartmentalization can enhance catalytic efficiency. |

| Urease in BSA-PEG Droplets [27] | Protein Droplets (~430 mg/mL BSA) | N/A | Slightly decreased kcat/Km (3x increase in K_m) | Crowding can inhibit substrate access without majorly altering the catalytic rate. |

Table 2: Impact of Crowding on Metamorphic Protein Equilibria [22]

| Protein | Switching Timescale | Crowding Agent | Effect on Population (Inactive State) | Effect on Switching Rate (k_ex) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XCL1 | Seconds | Ficoll 400 (90 g/L) | Increase (~7%) | Slight decrease |

| XCL1 | Seconds | PEG 10k (90 g/L) | Increase (~21%) | Large decrease (~57%) |

| KaiB (G89A mutant) | Hours | Ficoll 400 (90 g/L) | Increase (~5%) | Slight decrease |

| KaiB (G89A mutant) | Hours | BSA (90 g/L) | Increase (~13%) | Decreased forward rate (k1) |

Conceptual Diagrams

The Energy Landscape Under Crowding

Experimental Workflow for Crowding Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methods for Crowding Research

| Reagent / Method | Function / Key Property | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | Inert, spherical, highly branched polymer. Minimizes soft interactions. | Often the first choice for mimicking "hard" excluded volume effects. Useful for equilibrium and kinetic folding studies [23] [24]. |

| Dextran 70 | Inert, flexible, linear polymer. Behaves as a quasi-random coil. | Comparison with Ficoll 70 helps disentangle the effects of crowder shape and rigidity [24]. |

| PEG (various MW) | Flexible polymer. Can induce both steric exclusion and chemical (soft) interactions. | Common and inexpensive, but potential for specific interactions requires careful interpretation of results [1] [22]. |

| BSA as a Crowder | High-concentration protein solutions provide a biologically relevant crowder. | Creates a complex, heterogeneous environment. Used in phase-separated droplet systems to mimic cytoplasmic crowding [27]. |

| Urea Denaturation | Probes protein stability and unfolded state compaction. | A decrease in the m-value is a key signature of crowder-induced unfolded state compaction [23]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Resolves atomic-level structure and dynamics; quantifies slow conformational exchange. | Ideal for studying metamorphic proteins and allosteric regulation under crowding [22]. |

| Fluorescence Quenching | Probes solvent accessibility of specific residues (e.g., Trp, Cys). | Used to directly demonstrate compaction of the denatured state under crowding [23]. |

Mimicking the Inside of a Cell: Methodologies and Applications for In Vitro Crowding Studies

In the context of enzyme kinetics research, the internal environment of a cell is not a dilute aqueous solution but a densely packed, viscous medium where macromolecules can occupy up to 40% of the cytoplasmic volume, with concentrations reaching 400-560 g/L [28] [20]. This phenomenon, known as macromolecular crowding, significantly influences biochemical processes by altering enzyme structure, dynamics, and interaction with substrates. A core thesis in this field is that understanding the distinct effects of different crowding agents is essential to bridge the gap between traditional in vitro kinetics and true in vivo function. This guide provides a technical overview of commonly used crowders, supported by experimental data and protocols, to assist researchers in making informed choices for their studies.

Understanding Crowding Agents: Mechanisms and Key Differences

Macromolecular crowding influences enzyme kinetics through two primary, often competing, mechanisms:

- Excluded Volume Effect: An entropic force where inert crowders reduce the available space, favoring more compact molecular states and potentially enhancing association reactions [28] [29].

- Soft Interactions: Weak, non-specific enthalpic interactions (e.g., electrostatic, hydrophobic, van der Waals) between the crowder and biological molecules, which can either stabilize or destabilize the enzyme [29] [20].

The net effect on an enzymatic reaction is a complex outcome of these mechanisms and is highly dependent on the specific crowder, enzyme, and experimental conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used in crowding studies.

| Reagent Name | Type | Key Characteristics & Function |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll [4] [20] | Synthetic Polymer | Highly-branched, near-spherical polysucrose. Often considered for volume exclusion studies due to its minimal "soft interactions," though this is not absolute. |

| Dextran [28] [4] | Synthetic Polymer | Linear and flexible polyglucose. Used to study excluded volume effects and can create a depletion layer that mitigates viscosity effects with large enzymes [4]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [29] [20] | Synthetic Polymer | Hydrophilic, non-ionic polymer. Effects are highly molecular weight-dependent; can stabilize via volume exclusion or destabilize via binding to hydrophobic protein surfaces [29]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [28] [30] | Protein Crowder | A biological mimetic that provides a more physiologically relevant crowding environment, introducing specific and non-specific interactions. |

| Egg White [28] | Complex Biological Mixture | A natural, heterogeneous mixture of over 40 proteins that most accurately simulates the complex crowded environment of a cell. |

Comparative Kinetics Data Under Crowding Conditions

The choice of crowder can lead to dramatically different, and sometimes opposing, kinetic outcomes. The following data, synthesized from recent studies, highlights these agent-specific effects.

Table 1: Crowder-Specific Effects on Enzyme Kinetics

| Enzyme | Crowding Agent | Observed Effect on Kinetics | Postulated Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) [28] | Dextran, BSA, Egg White | Decreased Vmax, Decreased Km (Glutamate) | Crowding favors a closed, less active enzyme conformation and promotes the formation of an abortive enzyme complex. |

| Yeast Alcohol Dehydrogenase (YADH) [4] | Ficoll, Dextran | Direction-dependent effects: Decreased Vmax & Km for ethanol oxidation; Increased Vmax for acetaldehyde reduction. | Combined result of excluded volume (increasing effective concentrations) and increased viscosity (slowing product release). |

| NS3/4A Protease [20] | Ficoll 400 | Increased initial & maximum velocity, Increased turnover number. | Enhanced substrate binding near the active site due to crowder-enzyme-substrate interactions. |

| NS3/4A Protease [20] | PEG 6000 | Decreased initial & maximum velocity, Decreased turnover number. | Stronger interactions with the enzyme, reducing diffusion and potentially altering structural dynamics. |

| Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase [30] | PEG 8000, BSA | Increased Kcat at low and high crowder concentrations (with PEG at 45°C). | Modelled via excluded volume theory, which increases the thermodynamic activity of the enzyme and substrate. |

| Muscle Glycogen Phosphorylase b [29] | PEG 20000 (PEG-20K) | Stimulated enzymatic activity at room temperature. | Crowder-induced changes to the enzyme's secondary and tertiary structure. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Experimental Design

Q1: My enzyme's activity decreased with one crowder but increased with another. Is this normal? Yes, this is a documented phenomenon. For example, Ficoll increased the activity of NS3/4A protease, while PEG decreased it [20]. This highlights the importance of "soft interactions." PEG may form more extensive hydrophobic interactions with the enzyme, altering its dynamics, whereas the structure of Ficoll may lead to different, less disruptive interactions that enhance substrate binding.

Q2: How does the molecular weight of a polymeric crowder like PEG influence its effect? The molecular weight is critical. Lower molecular weight PEGs (e.g., PEG 2000) may have fewer binding sites and interact better with unfolded protein states. In contrast, medium molecular weight PEGs can induce conformational changes through more stable binding. Higher molecular weight PEGs (e.g., PEG 20000) have a more compact structure and exert stronger excluded volume effects, but their direct chemical interactions may be reduced due to shielding within their coils [29].

Q3: Why should I consider using a biological mimetic like BSA or egg white instead of synthetic polymers? Synthetic polymers like Ficoll and Dextran are excellent for systematic studies to isolate the effects of specific parameters like size and concentration. However, protein crowders like BSA and complex mixtures like egg white more accurately represent the intracellular environment, which is heterogeneous and filled with molecules that engage in a wide range of weak, "soft" interactions. Studies show that crowders are not inert and can have distinct effects on enzyme structure and function [28] [20]. Using biological mimetics helps bridge the gap between simplified in vitro models and cellular reality.

Q4: How can I determine if the observed effect is due to volume exclusion or chemical interactions? A standard protocol is to compare a large polymer with its small-molecule counterpart. For instance, compare the effects of Dextran (a polymer of glucose) with Glucose. Since glucose is too small to create significant excluded volume, any effects it has are likely due to soft interactions. If Dextran has a significantly different effect, the excluded volume effect is likely a major contributor. This approach was used in a GDH study to confirm that the pKa shift of a critical lysine was due to dextran's excluded volume, as glucose did not cause the shift [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Crowding Effects on Enzyme Kinetics

The following workflow, based on methodologies from the cited literature [28] [29] [4], provides a template for conducting crowding studies.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution of your chosen crowding agent (e.g., 400 g/L) in the appropriate assay buffer. Ensure the solution is well-mixed and allow it to equilibrate to the experimental temperature. The high viscosity of some agents may require extended mixing or gentle heating.

- Prepare stock solutions of the enzyme and substrate in the same buffer.

Crowded Assay Setup (for a single crowder type and concentration):

- In a reaction vessel, combine the assay buffer, crowder stock, and substrate stock to achieve the desired final crowder concentration and a range of substrate concentrations. The total reaction volume must be consistent across all trials.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme stock solution. Mix thoroughly but carefully to avoid introducing air bubbles, which can interfere with some detection methods.

- Immediately begin monitoring the reaction (e.g., via absorbance, fluorescence) to determine the initial velocity at each substrate concentration.

- Control: Run identical assays in parallel using the same buffer but without any crowding agent.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the initial velocity (v₀) against substrate concentration ([S]) for both the crowded and control assays.

- Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten model (or another appropriate model) to determine the apparent kinetic parameters Km and Vmax.

- Compare the parameters from the crowded assays to the control. A change in Km typically suggests an altered enzyme-substrate affinity, while a change in Vmax points to an effect on the catalytic rate constant (kcat) or product release.

Decision Framework for Crowder Selection

The following diagram synthesizes the information in this guide into a logical pathway for selecting the appropriate crowding agent based on the research objective.

Advanced Considerations: Integrating Osmolytes and Computational Tools

Combining Crowders with Osmolytes: The cellular environment contains both crowders and osmolytes (e.g., trehalose, betaine). Research on glycogen phosphorylase b shows that osmolytes can counteract the effects of crowders. For instance, trehalose was found to completely remove the stimulatory effect of PEG on the enzyme's activity [29]. Designing experiments that include both crowders and osmolytes can provide a more nuanced view of physiological regulation.

Leveraging Computational Simulations: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a powerful tool for deciphering the molecular mechanisms behind observed crowding effects. For example, atomistic simulations of the NS3/4A protease revealed that while both PEG and Ficoll form contacts with the enzyme and slow its diffusion, they do so to different extents and have distinct impacts on substrate binding and enzyme dynamics [20]. Integrating simulation data with experimental kinetics can offer a complete picture from molecular interaction to functional output.

Macromolecular crowding refers to the effects exerted on molecular reactions and processes by the highly concentrated, volume-occupied environment inside cells, which can occupy up to 30% of the total volume [31]. Traditional biochemical assays are performed in dilute, ideal solutions, which can lead to results that differ by orders of magnitude from the true in vivo kinetics and equilibria [31]. Integrating crowding into standard assays is therefore essential for obtaining physiologically relevant data. This guide provides practical protocols and troubleshooting for researchers aiming to study enzyme kinetics under such conditions.

FAQ: Core Principles of Crowding

Q: Why does macromolecular crowding affect biochemical reactions? A: Crowding creates an excluded volume effect. High concentrations of inert macromolecules reduce the available solvent volume for other molecules, increasing their effective concentrations and thermodynamic activities. This favors processes that reduce the total excluded volume, such as protein folding, binding, and association [31].

Q: How do "excluded volume effects" differ from "soft interactions"? A: Excluded volume effects are primarily entropic, driven by the steric exclusion of molecules from a shared volume. Soft interactions (or chemical interactions) are enthalpic and can include weak, non-specific attractions or repulsions between the crowding agent and your proteins of interest. The overall effect of a crowder is a combination of both [28] [4].

Q: My enzyme's kinetics are different in a crowded environment. Is this expected?

A: Yes, this is the central finding of crowding research. Crowding can decrease the rate of diffusion, shift conformational equilibria, stabilize or destabilize specific enzyme forms, and alter sensitivity to allosteric effectors, all of which can change the observed Michaelis-Menten parameters (Vmax and Km) [28] [1] [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Michaelis-Menten Kinetics under Crowding

This protocol outlines the steps to adapt a standard enzyme kinetics assay to incorporate crowding agents, using the study of Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH) as a model [28].

Key Reagents:

- Purified enzyme (e.g., GDH).

- Substrates and cofactors (e.g., glutamate, NAD+).

- Assay buffer (note: crowding effects can be pH-dependent [28]).

- Crowding agents (e.g., dextran, Ficoll, BSA, PEG - see Section 4 for selection).

Detailed Methodology:

- Prepare Crowded Assay Solutions: Prepare a concentrated stock solution of your chosen crowding agent in the assay buffer. Use this stock to dilute your enzyme, substrates, and cofactors to the desired final concentrations. Ensure proper mixing, as viscous solutions can be challenging to handle.

- Include Controls: For every experiment, run parallel controls in dilute buffer (no crowder) and with the small-molecule counterpart of your crowder (e.g., glucose for dextran). This helps distinguish excluded volume effects from soft chemical interactions [28].

- Measure Initial Velocities: For each crowded condition, perform the standard enzyme assay to measure the initial reaction velocity (

v0) across a range of substrate concentrations. - Account for Viscosity: The high viscosity of crowded solutions can affect mixing and pipetting accuracy. Allow more time for mixing and use positive-displacement pipettes for highly viscous solutions [32].

- Data Analysis: Plot

v0versus substrate concentration for each condition and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to extractKmandVmax. Compare these parameters to your dilute control to determine the crowding effect.

The workflow below summarizes the key steps and considerations for this protocol:

Protocol: Differentiating Crowding Mechanisms

To determine whether an observed effect is due to excluded volume or soft interactions, a comparative assay can be used [28] [33].

Key Reagents:

- Large, polymeric crowder (e.g., dextran 70, Ficoll 70).

- Its small-molecule counterpart (e.g., glucose, ethylene glycol).

Detailed Methodology:

- Design Parallel Experiments: Set up three sets of identical kinetic assays:

- Set A: In dilute buffer.

- Set B: In buffer containing a high concentration of a large crowder (e.g., 100 g/L dextran).

- Set C: In buffer containing a concentration of the small-molecule control (e.g., 100 g/L glucose) that matches the chemical composition of the large crowder but cannot exert significant excluded volume.

- Measure and Compare: Measure the kinetic parameters (

Km,Vmax) or binding affinities in all three sets. - Interpret Results:

- If the effect is seen in Set B but not Set C, it is likely dominated by excluded volume.

- If the effect is seen in both Set B and Set C, soft chemical interactions are likely playing a major role.

- A combination of both is common.

- Design Parallel Experiments: Set up three sets of identical kinetic assays:

The logical relationship for interpreting the results of this protocol is as follows:

Troubleshooting Guide

The following table addresses common problems encountered when working with crowded assays.

| Observation | Possible Cause | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in replicate measurements | - Incomplete mixing of viscous solutions.- Pipetting errors due to high viscosity. | - Extend vortexing/mixing time.- Use positive-displacement pipettes.- Pre-mix all solutions thoroughly before dispensing. |

| Unexpected precipitation or protein aggregation | - Crowding can enhance aggregation of unstable proteins [31].- Specific, unfavorable interactions with the crowder. | - Check enzyme stability in crowder via CD spectroscopy or native PAGE.- Switch to a different type of crowding agent (e.g., from PEG to Ficoll). |

| No observable crowding effect | - The enzyme or reaction may be insensitive to crowding [33].- Crowder concentration may be too low. | - Increase the concentration of the crowding agent (e.g., to 100-200 g/L).- Use a more complex crowder like BSA or a protein mixture [28]. |

| Apparent enzyme inhibition | - Viscosity slowing product release (a kinetic bottleneck) [4].- Crowding stabilizes a less active enzyme conformation [28] [1]. | - Compare with small viscogen control.- Investigate if crowding alters sensitivity to known allosteric effectors. |

| Altered fluorescence signals in coupled or FRET assays | - Crowders can cause inner-filter effects by scattering light.- Direct interaction between fluorophore and crowder. | - Include appropriate crowder controls for fluorescence baselines.- Use a different detection method if possible (e.g., radioactivity). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate crowding agent is critical for experimental design. The table below summarizes common agents and their properties.

| Reagent | Type & Common Examples | Key Characteristics & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Polymers | - Ficoll 70/400- Dextran 70/200- Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | - Pros: Chemically well-defined, systematic control over size/concentration.- Cons: Can have weak chemical (soft) interactions; not perfectly inert [28] [4]. |

| Protein Crowders | - Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)- Ovalbumin- Cell Lysates | - Pros: More biologically relevant, mimic the intracellular environment well.- Cons: Risk of specific enzymatic or inhibitory activity; can aggregate [28]. |

| Complex Mixtures | - Egg White [28]- Hemolysate | - Pros: Highly heterogeneous, best representation of in vivo conditions.- Cons: Complex and poorly defined composition; potential for interference. |

| Small Molecule Controls | - Glucose (for Dextran)- Sucrose (for Ficoll)- Ethylene Glycol (for PEG) | - Function: Critical controls to distinguish excluded volume from soft chemical interactions [28] [33]. |

FAQ: Advanced Applications & Data Interpretation

Q: Can crowding affect allosteric regulation? A: Yes. Research on GDH has shown that macromolecular crowding can abrogate activation by leucine but does not diminish inhibition by GTP. This indicates that crowding can differentially regulate allosteric networks, potentially by stabilizing specific enzyme conformations [28].

Q: How does pH interact with crowding effects? A: The effects are often interdependent. For GDH, crowding favors a closed, less active conformation at lower pH (~7), promoting the formation of an abortive enzyme complex. The crowded environment can also alter the pKa of critical catalytic residues [28]. Always consider and control for pH in crowding experiments.

Q: Are crowding effects always universal for a given enzyme?

A: No. Effects can be reaction-specific. For yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (YADH), crowding decreased Vmax and Km for the oxidation of ethanol, but had the opposite or no effect on the reverse reaction (reduction of acetaldehyde) [4]. Always test the specific reaction of interest.

Troubleshooting Guide: Enzyme Kinetics in Crowded Conditions

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when studying enzyme kinetics under macromolecular crowding conditions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Noisy spectra, unstable baselines in spectrophotometry [34]. | Instrument vibration; dirty optics or ATR crystals [34]. | Isolate spectrometer from vibrations; clean optical windows and ATR crystals with recommended solvents before use [35] [34]. |

| Data Quality | Significant result variation between identical sample replicates [35]. | Improper sample preparation leading to contamination; instrument calibration drift [35]. | Regrind samples to remove surface contamination; avoid touching sample surfaces; perform recalibration with freshly prepared standards [35]. |

| Activity & Kinetics | Enzyme activity decreases with crowding agents [1]. | Suppressed conformational dynamics (e.g., flap opening in HIV-1 protease); reduced diffusion encounter rates [1]. | Test different crowder types/sizes; use ITC to circumvent issues with labeled substrates in turbid solutions [36]. |

| Activity & Kinetics | Enzyme activity increases with crowding agents, sometimes substrate-specifically [1]. | Stabilization of active conformation; excluded volume effect favoring compact states; altered solvation [1]. | Characterize conformational stability via H/D exchange; use ITC to measure binding affinity ((Km)) and catalytic rate ((k{cat})) under crowding [1] [36]. |

| Activity & Kinetics | Substrate-dependent response to crowding; unexpected inhibition [1] [36]. | Crowder-induced allosteric regulation; product inhibition amplified in crowded milieu [1] [36]. | Design control ITC experiments to identify inhibition mechanisms and estimate inhibition constants directly in crowded solutions [36]. |

| General Methodology | Difficulty applying standard "out" or "ref" parameters in kinetic analysis software. | Software architecture limitations in newer kinetic platforms for passing multiple output values [37]. | Use a single return statement that outputs a structured data string (e.g., delimited string, JSON) for multiple parameters, then parse the data in the calling function [37]. |

Workflow Diagram for Troubleshooting

The following diagram outlines a systematic troubleshooting methodology adapted from IT support frameworks to address complex experimental problems [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it crucial to study enzyme kinetics in crowded conditions rather than just dilute buffers? The cellular interior is densely packed with macromolecules (200–400 g/L), creating a crowded environment that can occupy 20–30% of the total volume [1] [36]. This crowding drastically alters fundamental parameters compared to dilute solutions: it reduces diffusion rates, shifts protein interaction equilibria, changes conformational dynamics and stability, and can enhance allosteric regulation [1]. Consequently, kinetic parameters ((Km), (k{cat})) measured in dilute buffers can differ by orders of magnitude from those in a more physiologically relevant, crowded milieu, impacting drug design and biochemical understanding [36].

Q2: My spectroscopic assays are unreliable in turbid, crowded solutions. What are my options? Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a powerful, label-free alternative for kinetic studies in crowded solutions [36]. Unlike spectrophotometric or fluorometric methods that require substrate labels and can be impaired by solution turbidity, ITC directly measures the heat generated or absorbed during a reaction. This allows for the direct determination of (Km), (k{cat}), and inhibition constants in the presence of high concentrations of crowders like proteins, PEG, or Ficoll without interference [36].