Beyond the Shallow Surface: Innovative Strategies for Targeting SH2 Domains in Drug Discovery

Targeting the shallow binding surfaces of Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains represents a significant challenge and opportunity in therapeutic development, particularly for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

Beyond the Shallow Surface: Innovative Strategies for Targeting SH2 Domains in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Targeting the shallow binding surfaces of Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains represents a significant challenge and opportunity in therapeutic development, particularly for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies to overcome the historical difficulties of inhibiting these protein-protein interaction modules. We explore the foundational structural biology of SH2 domains, delve into cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies for inhibitor design, address key challenges in achieving selectivity and potency, and review validation techniques that bridge the gap from in silico predictions to clinical application. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances to chart a course for the next generation of SH2 domain-targeted therapeutics.

Decoding SH2 Domain Architecture: From Canonical Binding to Novel Therapeutic Opportunities

SH2 Domain FAQs: Structure and Specificity

1. What is the fundamental structural paradox of SH2 domains? All SH2 domains share a highly conserved structural fold of approximately 100 amino acids, characterized by a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices. Despite this conserved architecture, different SH2 domains recognize distinct phosphotyrosine (pY) peptide motifs, achieving remarkable functional diversity. This specificity is primarily determined by surface loops that control access to binding pockets rather than changes to the core fold itself [1] [2] [3].

2. How do surface loops dictate binding specificity? The EF loop (connecting β-strands E and F) and BG loop (connecting α-helix B and β-strand G) function as "gatekeepers" that control ligand access to key specificity pockets. Through variations in their sequence and conformation, these loops can plug or open binding subsites, enabling different SH2 domains to recognize residues at P+2, P+3, or P+4 positions C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine [1] [4].

3. Why is the conserved arginine residue critical for function? An invariant arginine residue at position βB5 within the FLVR motif forms a bidentate salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of the phosphotyrosine. This interaction provides the majority of the binding energy and ensures phosphorylation-dependent recognition. Mutation of this residue abrogates pY binding both in vitro and in vivo [2] [3] [5].

4. How can the same structural fold accommodate diverse specificities? The conserved fold maintains the fundamental pY-binding function, while sequence variations in the loops create combinatorial control over which specificity pockets are accessible. This allows the same structural framework to recognize different peptide contexts with minimal disturbance to the overall domain architecture [1] [4].

5. What experimental approaches best characterize SH2 domain specificity? High-throughput methods including peptide library screening with bacterial or phage display, peptide arrays (OPAL), and next-generation sequencing coupled with computational modeling (ProBound) have proven effective for comprehensively profiling SH2 domain specificities and building accurate sequence-to-affinity models [6] [7] [8].

Experimental Protocols for SH2 Domain Analysis

Protocol 1: Bacterial Peptide Display with NGS for Affinity Profiling

Principle: This method combines bacterial display of genetically-encoded peptide libraries with enzymatic phosphorylation of displayed peptides, affinity-based selection, and next-generation sequencing to quantitatively profile SH2 domain binding specificity across highly diverse peptide libraries [6].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Library Construction: Generate random phosphopeptide libraries (10⁶-10⁷ sequences) displayed on bacterial surfaces with degenerate sequences flanking the central tyrosine residue.

- Enzymatic Phosphorylation: Treat displayed peptides with tyrosine kinases to generate phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) residues in situ.

- Affinity Selection: Incubate phosphorylated library with the SH2 domain of interest; separate bound from unbound populations using magnetic beads or FACS.

- Multi-Round Selection: Perform 3-5 rounds of selection to enrich high-affinity binders while maintaining diversity.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Sequence input and selected populations after each round to obtain quantitative count data.

- ProBound Analysis: Use the ProBound computational framework to analyze multi-round NGS data and build additive models that predict binding free energy across the full theoretical sequence space [6].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low Enrichment: Ensure proper phosphorylation efficiency by optimizing kinase concentration and reaction time.

- High Non-specific Binding: Include control selections with unphosphorylated library or competition with excess pY peptide.

- Limited Diversity: Use highly complex input libraries (>10⁶ sequences) and avoid excessive selection rounds that dramatically reduce sequence diversity.

Protocol 2: Combinatorial Peptide Library Screening with PED/MS

Principle: The "one-bead-one-compound" approach screens SH2 domains against synthetic pY peptide libraries chemically synthesized on solid support, identifying high-affinity binders through enzymatic detection followed by partial Edman degradation and mass spectrometry for sequencing [7].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Library Synthesis: Use split-and-pool synthesis on TentaGel beads to create a library of pY peptides with 5 randomized positions (TAXXpYXXXLNBBRM-resin), where X represents 18 proteinogenic amino acids (excluding Cys and Met) plus norleucine and α-aminobutyric acid.

- Screening: Incubate beads with tagged SH2 domain, detect binding with enzyme-linked immunoassay using anti-tag antibodies.

- Positive Bead Isolation: Manually pick beads showing positive binding signals.

- Peptide Sequencing: Sequence individual beads using partial Edman degradation coupled with mass spectrometry (PED/MS).

- Motif Analysis: Align sequences from positive beads to determine consensus binding motif [7].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Weak Detection Signal: Optimize antibody concentration and detection substrate incubation time.

- High Background: Include stringent washes with detergents (e.g., 0.1% Tween-20) and competitive inhibitors (e.g., free pY).

- Ambiguous Sequencing: Confirm sequences with tandem mass spectrometry when PED results are unclear.

SH2 Domain Structural Features and Classification

Table 1: Key Structural Elements Governing SH2 Domain Function

| Structural Element | Location | Functional Role | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| pY-binding pocket | Formed by βB, βC, βD, αA, BC loop | Binds phosphotyrosine via invariant ArgβB5 | Highly conserved across all SH2 domains |

| Specificity pocket | Hydrophobic cavity molded by EF and BG loops | Determines preference for residues C-terminal to pY | Variable; defines specificity classes |

| EF loop | Connects β-strands E and F | Controls access to P+2/P+3 binding pockets | Sequence and length variable |

| BG loop | Connects α-helix B and β-strand G | Controls access to P+3/P+4 binding pockets | Sequence and length variable |

| Central β-sheet | Core of SH2 domain | Provides structural scaffold | Highly conserved fold |

Table 2: Major SH2 Domain Specificity Classes

| Specificity Class | Representative Domains | Preferred Motif | Key Structural Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| P+3 binders | SRC, FYN, ABL1, NCK1 | pY[-][-]ψ (ψ = hydrophobic) | Open P+3 pocket; accessible hydrophobic cavity |

| P+2 binders | GRB2, GADS, GRB7 | pYxN (Asn at P+2) | EF loop blocks P+3 pocket; hydrogen bonding to Asn |

| P+4 binders | BRDG1, BKS, CBL | pYxxxψ (ψ = hydrophobic) | BG loop plugs P+3 pocket; open P+4 basket |

| STAT type | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5 | pYxxQ (Gln at P+3) | Lack βE and βF strands; distinct dimerization interface |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Key Features | Reference Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random peptide libraries | Bacterial/phage display | 10⁶-10⁷ diversity; central tyrosine for phosphorylation | [6] |

| One-bead-one-compound libraries | Solid-phase screening | TAXXpYXXXLNBBRM format; 18 amino acids + surrogates | [7] |

| High-density pTyr peptide chips | Specificity profiling | 6,200+ human phosphopeptides; SPOT synthesis technology | [8] |

| ProBound software | Data analysis & modeling | Free-energy regression; multi-round NGS data analysis | [6] |

| NetSH2 predictors | In silico binding prediction | Artificial neural networks trained on experimental data | [8] |

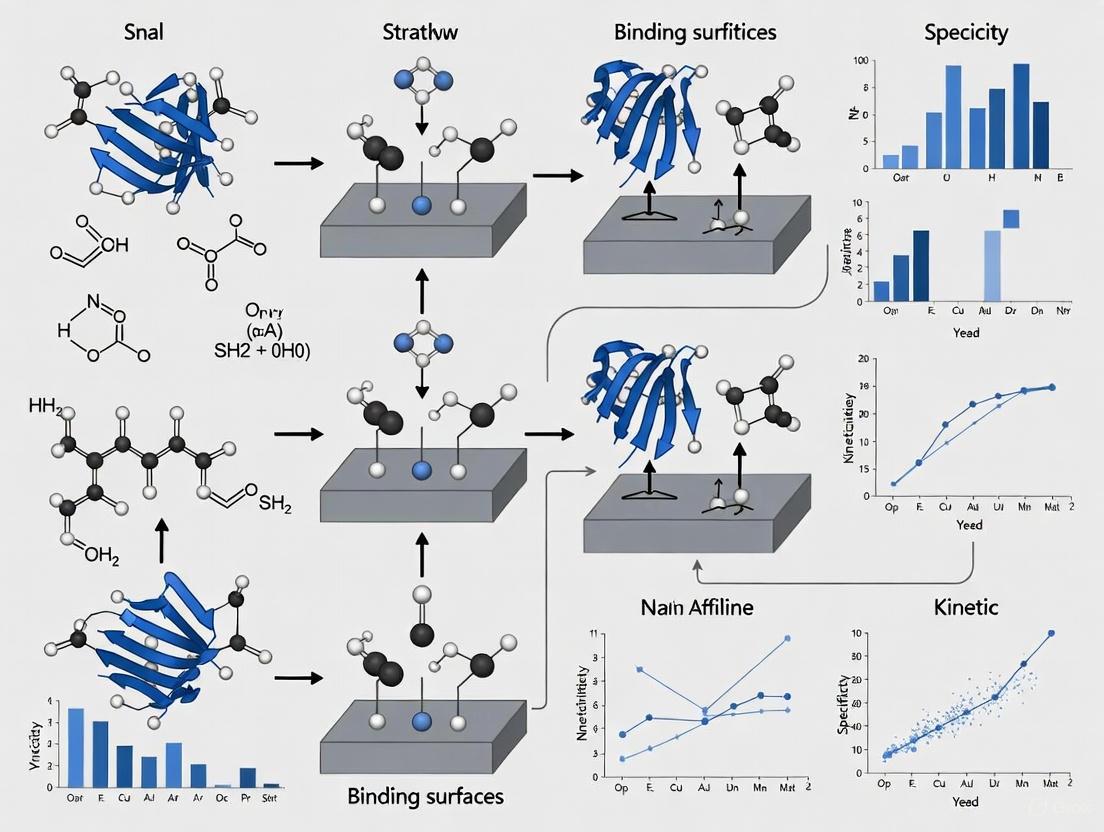

Structural and Mechanism Visualization

SH2 Domain Structure-Function Relationship

High-Throughput Specificity Profiling Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides: Resolving Experimental Challenges in SH2 Domain Research

Issue 1: Low Binding Affinity or Unexpected Specificity in SH2:Peptide Interactions

Problem: Your assay shows weaker-than-expected binding affinity or detects interactions with non-cognate peptides, potentially due to unconventional SH2 binding mechanisms.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-canonical FLVR motif | Sequence alignment against known unusual SH2s (e.g., SPT6, Legionella); Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) to measure binding thermodynamics [9] [10]. | Use degenerate peptide libraries to profile specificity; do not assume binding relies solely on +3 position. |

| Dual phosphotyrosine requirement | Design peptides with varying pY-pY spacing; use Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) or Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) to check for domain compaction [11]. | Ensure peptide ligands contain two appropriately spaced phosphotyrosines (e.g., for p120RasGAP). |

| Inhibitory SH2 conformation | Compare binding in presence/absence of regulatory proteins (e.g., p85β cSH2); use Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) to detect allosteric changes [12] [13]. | Employ activating phosphopeptides that extend beyond pYXXM motif to relieve autoinhibition. |

Verification Protocol: After implementing solutions, verify binding using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) with a negative control SH2 domain containing a mutated FLVR arginine (R→K). A true positive interaction should show >100-fold reduced affinity in the mutant [9] [10].

Issue 2: Difficulty in Targeting Shallow SH2 Binding Surfaces

Problem: Small-molecule inhibitors fail to bind or show poor specificity due to the extensive, flat protein-protein interaction interface.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Experiments | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of deep binding pockets | Conduct high-throughput crystallography/fragment screening; map surface topology with alanine scanning mutagenesis [14] [2]. | Develop bivalent inhibitors targeting both pY pocket and secondary surface sites; use pTyr bioisosteres (e.g., 4'-phosphonodifluoromethyl phenylalanine). |

| Lipid-mediated membrane recruitment | Perform co-sedimentation assays with PIP2/PIP3 lipids; create SH2 domain mutants in cationic lipid-binding region [2]. | Design hybrid molecules that target both SH2 domain and membrane phospholipids; consider allosteric inhibition via lipid-binding pocket. |

| Phase separation-mediated clustering | Use fluorescence microscopy to visualize SH2 condensation; Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) to assess dynamics [2]. | Develop inhibitors that disrupt multivalent interactions driving liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). |

Verification Protocol: Test cellular efficacy using a GRB2 SH2 inhibition assay. A successful inhibitor should block EGF-induced SOS recruitment and RAS activation, measured by GST-RAF1 RBD pull-down, without affecting SRCC SH2 domain interactions [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common unusual features found in SH2 domains beyond the canonical FLVR motif?

The most frequently observed atypical features include: (1) Recognition of non-tyrosine phosphorylation: The ancestral SPT6 SH2 domain binds phospho-threonine and phospho-serine peptides from RNA polymerase II [9] [10]. (2) Unusual binding pockets: Legionella pneumophila SH2 domains lack selectivity pockets and use large loop inserts to "clamp" pTyr peptides with high affinity but low sequence specificity [9]. (3) Multiple pTyr recognition sites: Some SH2 domains, like those in p85β, have secondary binding sites that require extended peptide motifs beyond the canonical pYXXM [12] [13]. (4) Dual pY binding: Tandem SH2 domains in proteins like p120RasGAP synergistically bind two phosphotyrosines, inducing compaction of the SH2-SH3-SH2 module [11].

Q2: How can I experimentally distinguish between canonical and atypical SH2 binding mechanisms?

A three-step experimental approach is recommended: First, perform systematic peptide library screening (e.g., bacterial peptide display with NGS) to map binding specificity beyond the +3 position [6]. Second, use structural analysis (X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM) to visualize peptide-bound complexes, paying attention to FLVR motif conformation and secondary interaction surfaces [9] [11]. Third, conduct binding affinity measurements (SPR or ITC) with wild-type and mutant SH2 domains (e.g., FLVR arginine mutation) - atypical binding often shows significant residual affinity even when the canonical pTyr pocket is compromised [9] [10].

Q3: What strategies are most effective for targeting shallow SH2 binding surfaces in drug development?

Successful strategies include: (1) Bivalent inhibitors that simultaneously engage both the pTyr pocket and secondary surface sites [14] [2]. (2) pTyr bioisosteres that mimic the phosphate group while improving pharmacodynamics (e.g., difluoromethyl phosphonate) [14]. (3) Allosteric inhibition targeting lipid-binding sites or regulatory interfaces, as demonstrated for Syk kinase where nonlipidic inhibitors target the lipid-protein interaction interface [2]. (4) Disruption of phase separation by targeting multivalent interactions that drive SH2 domain condensation in signaling clusters [2].

Experimental Protocols for Studying Atypical SH2 Binding

Protocol 1: Profiling SH2 Specificity Using Bacterial Peptide Display and NGS

Purpose: To quantitatively map SH2 domain binding specificity across theoretical sequence space [6].

Workflow:

Key Reagents:

- Random peptide library: Degenerate oligonucleotides encoding pY-centered 9-mer peptides with flanking random sequences [6].

- SH2 domain: Recombinantly expressed with affinity tag (GST or His).

- ProBound software: For computational analysis of NGS data and free energy regression [6].

Procedure Details:

- Library construction: Clone degenerate oligonucleotide library into bacterial display vector. Validate library diversity by NGS of input population.

- Affinity selection: Incubate library with immobilized SH2 domain for 1h at 4°C. Wash with low-stringency buffer (50mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20). Elute bound peptides with free pTyr (10mM) or high pH buffer.

- NGS preparation: Amplify recovered peptides by PCR using barcoded primers. Sequence on Illumina platform to obtain ≥100,000 reads per selection round.

- Computational analysis: Input NGS count data into ProBound to train additive model predicting ΔΔG for any peptide sequence.

- Validation: Synthesize top 10 predicted binders and measure affinity by ITC. Model should achieve R² > 0.85 between predicted and measured ΔΔG [6].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Tandem SH2 Domain Binding by SAXS

Purpose: To analyze conformational changes in tandem SH2 domains upon dual phosphotyrosine engagement [11].

Workflow:

Key Reagents:

- Tandem SH2 protein: Recombinant SH2-SH3-SH2 module (e.g., p120RasGAP residues 1-300) [11].

- Dual pY peptide: Biotinylated peptide containing two phosphotyrosines with appropriate spacing (e.g., p190RhoGAP derived).

- SAXS instrument: Synchrotron-based beamline with in-line size exclusion chromatography.

Procedure Details:

- Sample preparation: Purify SH2-SH3-SH2 module to >95% homogeneity by SEC. Confirm monodispersity by DLS.

- Complex formation: Incubate protein with 1.2 molar excess of dual pY peptide for 30min at 4°C.

- SAXS data collection: Collect scattering data for apo and peptide-bound protein at multiple concentrations (1-5 mg/mL). Perform SEC-SAXS to eliminate aggregation.

- Data analysis: Calculate radius of gyration (Rg) and maximum dimension (Dmax) from Guinier plot and pair distribution function. Compare Kratky plots to assess rigidity.

- Structural interpretation: Use ensemble optimization to model conformational changes. Tandem SH2 domains typically show compaction upon dual pY binding, with Rg decreasing by 10-15% [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Libraries | Random pY 9-mer library; Proteome-derived peptide library [6] | Specificity profiling; Native interaction mapping | High diversity (10^6-10^7); Framed around fixed pY; Compatible with display technologies |

| Expression Systems | E. coli SH2 expression; Baculovirus for tandem domains [11] | Recombinant protein production | High yield for isolated domains; Proper folding for complex multi-domain proteins |

| Bioinformatic Tools | ProBound; SH2 signature motif database [6] [9] | Data analysis; Specificity prediction | Free-energy regression from NGS data; Catalog of canonical and unusual binding motifs |

| Binding Assays | SPR; ITC; FP [9] [11] | Affinity measurement; Thermodynamic profiling | Label-free kinetics; Complete thermodynamic profile; High-throughput capability |

| Structural Methods | X-ray crystallography; SAXS; HDX-MS [12] [11] | 3D structure determination; Solution conformation analysis | Atomic resolution; Solution state information; Dynamics and allostery |

| Cellular Assays | GRB2 inhibition; Phase separation imaging [14] [2] | Functional validation; Pathological relevance | Pathway-specific readout; Visualization of biomolecular condensates |

Structural Mechanisms of Atypical SH2 Domains

Visualizing Unusual SH2 Binding Modes:

Quantitative Data on Unusual SH2 Binding Properties:

| SH2 Domain Type | Key Structural Feature | Binding Affinity (Kd) | Specificity Determinants | Biological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical (Src) | Conserved FLVR arginine [9] | 0.1-10 μM [15] [2] | +3 residue relative to pY [9] [15] | Signal transduction |

| SPT6 (Ancestral) | FLVR binds pThr, accommodates Tyr [9] [10] | Not reported | pT-X-Y motif [10] | Transcription elongation |

| Legionella LeSH | Large EF loop insert, clamping mechanism [9] | High affinity (low nM range) | Minimal sequence specificity [9] | Host pathogen interaction |

| p85β cSH2 | Exposed pY site, distal inhibitory contact [12] [13] | ~10 μM (peptide) [12] | Extended motif beyond pYXXM [12] [13] | PI3K regulation |

| p120RasGAP Tandem | Two SH2 domains in SH2-SH3-SH2 cassette [11] | ~100 nM (dual pY) [11] | Spacing between two pY residues [11] | Ras/Rho signaling crosstalk |

FAQs: Troubleshooting SH2 Domain Research

Q1: Our SH2 domain inhibitors show poor selectivity in cellular assays. What could be the cause?

A1: Poor selectivity often stems from the high structural conservation across the 120 human SH2 domains. To address this:

- Investigate Specificity Pockets: Focus on the EF and BG loops of your target SH2 domain. These loops control access to ligand specificity pockets and are a primary source of natural binding diversity [2]. Design compounds that exploit unique amino acid residues in these regions.

- Utilize Advanced Screening: Employ platforms that integrate DNA-encoded libraries and massively parallel structure-activity relationship (SAR) determination to rapidly identify selective lead compounds, as demonstrated in the development of Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) SH2 inhibitors [16].

- Consider Allosteric Inhibition: Explore regions outside the conserved phosphotyrosine (pY) pocket. For example, some synthetic binding proteins (monobodies) achieve strong selectivity for Src family kinase (SFK) SH2 domains by binding to distinct, non-overlapping surfaces [17].

Q2: What are the best practices for validating that a compound acts by disrupting SH2 domain-phosphotyrosine interactions?

A2: A multi-faceted approach is required for rigorous validation.

- Direct Binding Assays: Use isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or fluorescence polarization (FP) assays to confirm that your inhibitor directly binds to the SH2 domain and competes with pY-containing peptides [17].

- Cellular Pathway Analysis: In cell-based assays, monitor the inhibition of downstream signaling events known to be dependent on the target SH2 domain. For instance, a BTK SH2 inhibitor should robustly inhibit proximal SH2-dependent phosphorylation signaling (e.g., pERK) and downstream immune cell activation markers (e.g., B cell CD69 expression) [16].

- Interactome Analysis: For a global view, express the SH2 domain intracellularly as a bait and use tandem affinity purification-mass spectrometry (TAP-MS) to confirm that the inhibitor disrupts the domain's interaction with its physiological protein partners without affecting other SH2-containing proteins [17].

Q3: How can we overcome the challenge of targeting the shallow and featureless pY-binding surface?

A3: The shallow binding surface is a key challenge. Emerging strategies include:

- Targeting Non-Canonical Binding Sites: Look beyond the pY pocket. SH2 domains can bind lipid molecules like PIP2 and PIP3 at cationic sites near the pY-binding pocket. Targeting these lipid-binding sites offers a promising alternative for developing selective inhibitors [2].

- Exploiting Contextual Recognition: SH2 domains recognize both permissive residues (enhance binding) and non-permissive residues (oppose binding) in the peptide sequence. Understanding this complex "linguistics" allows for the design of inhibitors that mimic high-affinity, context-dependent physiological ligands [18].

- Using Protein-Based Inhibitors: As an alternative to small molecules, monobodies can be engineered to bind SH2 domains with high affinity and selectivity, often by engaging surfaces that are difficult to target with traditional small molecules [17].

Q4: Are SH2 domains relevant targets in neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) like Alzheimer's?

A4: Yes, emerging research implicates SH2 domain-containing proteins in NDs.

- The Case of Shp2: The phosphatase Shp2, which contains two SH2 domains, is a core component of feedback networks in NDs. It is linked to pathogenic factors like oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation [19].

- Potential Therapeutic Target: In Alzheimer's disease, Shp2 interacts with the adaptor protein Gab2, which is involved in the formation of amyloid-β (Aβ). Treatment with Shp2 inhibitors has been shown to reduce the accumulation of Aβ in neuronal cells, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target [19].

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Fluorescence Polarization (FP) Competition Binding Assay

Purpose: To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of a novel compound by measuring its ability to compete with a fluorescent pY-peptide for binding to a recombinant SH2 domain [18].

Workflow:

Materials:

- Recombinant SH2 domain protein, purified (e.g., via GST-tag in E. coli [18]).

- Fluorescently-labeled pY-peptide corresponding to a known physiological ligand.

- Black, flat-bottom, low-volume 384-well microplates.

- Plate reader capable of measuring fluorescence polarization.

- Test compounds in a serial dilution series.

Procedure:

- Prepare a master mixture containing the recombinant SH2 domain and the fluorescent pY-peptide at a concentration near the Kd of their interaction in an appropriate assay buffer.

- Dispense the master mixture into the wells of the 384-well plate.

- Immediately add the serially diluted test compounds or DMSO vehicle control to the respective wells. Incubate the plate in the dark for 30-60 minutes at room temperature.

- Measure the fluorescence polarization (in millipolarization units, mP) for each well using the plate reader.

- Data Analysis: Plot the mP value against the logarithm of the inhibitor concentration. Fit the data to a sigmoidal dose-response curve to determine the IC50 value.

Protocol 2: SPOT Peptide Array Analysis for SH2 Domain Specificity Profiling

Purpose: To semiquantitatively profile the binding specificity of an SH2 domain across a large library of physiological pY-peptide sequences [18].

Workflow:

Materials:

- Custom peptide array membrane synthesized with 11-amino-acid-long pY-peptides, where the phosphotyrosine is fixed at the fifth position [18].

- Purified SH2 domain protein (e.g., as a GST-fusion).

- Anti-GST primary antibody and compatible HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Chemiluminescence detection kit and imaging system.

Procedure:

- Block the peptide array membrane with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Incubate the membrane with the purified SH2 domain protein in blocking buffer for 2 hours.

- Wash the membrane thoroughly with TBST to remove non-specifically bound protein.

- Incubate with an anti-GST primary antibody, followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

- Develop the membrane using a chemiluminescence substrate and image the signals.

- Data Analysis: The intensity of each spot corresponds to the relative binding affinity of the SH2 domain for that particular pY-peptide sequence. This allows for the identification of permissive and non-permissive residues surrounding the pY [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain-Targeted Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics / Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains (GST-tagged) | Used in direct binding assays (FP, ITC, SPOT) to characterize interactions and screen inhibitors. | Purified from E. coli; Essential for biophysical and structural studies [18] [17]. |

| Monobodies | Synthetic binding proteins used as high-affinity, selective inhibitors to perturb specific SH2 domain functions in cells. | Can discriminate between subfamilies (e.g., SrcA vs. SrcB); Tool for dissecting SFK functions [17]. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) | Integrated discovery platforms for identifying potent and selective small-molecule inhibitors of challenging targets like SH2 domains. | Used in platform integrating custom DELs and parallel SAR; Enabled discovery of BTK SH2 inhibitor [16]. |

| SPOT Peptide Arrays | Semiquantitative method for high-throughput profiling of SH2 domain binding specificity against hundreds of physiological pY-peptides. | Nitrocellulose membrane with addressable peptides; Reveals contextual sequence recognition [18]. |

| SH2 Domain Inhibitors (Clinical Stage) | Validates the therapeutic relevance of SH2 domains. Provides benchmarks for novel inhibitor development. | STAT3, STAT6, and BTK SH2 inhibitors have reached clinical development [20] [16]. |

Quantitative Data on SH2 Domain Characteristics and Targeting

Table 2: Quantitative and Structural Data on SH2 Domains and Inhibitors

| Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Significance / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Human SH2 Domain Count | 121 domains in 110 proteins [5] [21] | Highlights the extensive network of pY-mediated signaling and the challenge of achieving selectivity. |

| Binding Affinity (Kd) | 0.1 - 10 µM for physiological pY-ligands [2] | Moderate affinity allows for specific, yet reversible and regulatable, signaling interactions. |

| SH2 Domain Length | ~100 amino acids [5] [22] [23] | Defines a compact, modular unit that is highly structured. |

| Key Conserved Residue | Arginine at position βB5 (part of FLVR motif) [2] | Forms a critical salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of pY; essential for binding. |

| BTK SH2 Inhibitor Selectivity | Best-in-class; No off-target inhibition of TEC kinase [16] | Demonstrates the potential for superior selectivity by targeting SH2 domains instead of kinase domains. |

FAQs: Understanding SH2 Domain Mechanisms

Q1: What are the non-canonical functions of SH2 domains beyond phosphotyrosine (pY) binding? Emerging research shows that SH2 domains have two significant non-canonical roles. First, approximately 75% of human SH2 domains can bind to membrane lipids, particularly phosphoinositides like PIP₂ and PIP₃, with high affinity and specificity [2] [24]. This lipid-binding activity is evolutionarily conserved and plays a crucial role in membrane recruitment and the modulation of catalytic activity [25]. Second, SH2 domains participate in biomolecular phase separation, driving the formation of membraneless organelles and signaling condensates through multivalent interactions [2]. This process, known as liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), enhances signaling efficiency in pathways such as T-cell receptor signaling [2].

Q2: How does lipid binding influence SH2 domain function in cellular signaling? Lipid binding controls membrane localization and regulates the activity of SH2 domain-containing proteins. For instance, lipid interaction modulates the scaffolding function of SYK, facilitating non-catalytic STAT3/5 activation [2]. For ABL tyrosine kinase, PIP₂ binding via its SH2 domain is essential for membrane recruitment and activity modulation [2] [24]. This lipid-binding capability allows SH2 domains to browse membrane lipids in addition to tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins to find matching partners, thereby increasing the specificity and efficiency of signal transduction [24].

Q3: What is the role of SH2 domains in biomolecular condensates? SH2 domains contribute to the formation of biomolecular condensates via multivalent interactions. In T-cells, interactions among GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor drive condensate formation through LLPS, enhancing T-cell receptor signaling amplitude and efficiency [2]. In kidney podocyte cells, phase separation of adapter protein NCK, which contains an SH2 domain, increases the membrane dwell time of N-WASP and Arp2/3 complexes, promoting actin polymerization [2]. These condensates form signaling hubs that concentrate components to accelerate reactions and regulate pathway output.

Q4: How do disease-associated mutations affect SH2 domain lipid binding and phase separation? Studies indicate that many disease-causing mutations in SH2 domains are localized within their lipid-binding pockets, disrupting normal lipid interactions and leading to aberrant signaling [2]. In cancer and neurodegenerative diseases, aberrant phase separation behavior is observed; for example, mutant p53 forms irreversible dense condensates via LLPS, losing tumor-suppressive function while acquiring oncogenic properties [26]. Dysregulation of these processes can convert reversible liquid droplets into irreversible pathogenic aggregates or alter signal fidelity.

Troubleshooting Guides: Experimental Challenges

Table 1: Troubleshooting Lipid-Binding Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or no lipid binding signal in SPR | Non-physiological lipid vesicle composition | Use plasma membrane-mimetic vesicles containing 5-10% PIP₂ or PIP₃ in a PC/PS background [24]. |

| Low affinity binding despite high pY-peptide affinity | Overlap between lipid and pY-binding pockets | Test binding in the absence of competing pY ligands; mutagenesis of cationic residues (e.g., R152, R175 in Abl) can differentiate binding sites [24]. |

| Poor plasma membrane localization in vivo | Depletion of specific phosphoinositides | Validate lipid specificity in vitro; use pharmacological (e.g., wortmannin) or optogenetic tools to manipulate PIP₃ levels in cells [24]. |

| Inconsistent lipid binding affinities | Variations in protein purification tags | Use cleavable tags (e.g., TEV protease site) during purification to avoid steric interference with lipid-binding surfaces [24]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Phase Separation Studies

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irreversible condensate formation | Mutations or conditions promoting aggregation | Optimize buffer conditions (salt, pH, crowding agents); confirm reversibility by diluting the sample and observing dissolution [26]. |

| Failure to observe expected condensates | Lack of multivalency or insufficient component concentration | Ensure presence of multivalent components (e.g., proteins with multiple SH2/SH3 domains and their phosphorylated partners) [2] [26]. |

| Difficulty distinguishing functional condensates | Condensates exhibiting solid-like properties | Use fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) to assay for liquid-like dynamics and reversibility [26]. |

| Challenges in linking condensation to function | Lack of direct functional readouts | Correlate condensation with specific activity assays (e.g., kinase activity, actin polymerization) in reconstituted systems [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Protocol 1: Assessing SH2 Domain Lipid-Binding Specificity In Vitro

Purpose: To quantitatively characterize the affinity and specificity of SH2 domain binding to phosphoinositides. Materials: Purified SH2 domain protein, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor, L-α-phosphatidylcholine (PC), L-α-phosphatidylserine (PS), PIP₂, PIP₃. Method:

- Prepare lipid vesicles: Create vesicles mimicking the cytosolic plasma membrane leaflet (e.g., PC:PS:PIP₂ in 75:20:5 molar ratio) and vesicles with varied phosphoinositides for specificity screening [24].

- Immobilize lipid vesicles on SPR sensor chip L1 surface.

- Inject purified SH2 domain at a range of concentrations (e.g., 0.1-10 µM) in HEPES-buffered saline.

- Record binding kinetics (association/dissociation) and calculate equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) [24].

- Competition assay: Pre-incubate SH2 domain with a cognate pY-peptide (e.g., 100 µM) and monitor changes in lipid binding response.

Protocol 2: Reconstituting SH2 Domain-Mediated Phase Separation

Purpose: To observe and quantify phase separation driven by multivalent SH2 domain interactions. Materials: Recombinant SH2-containing proteins (e.g., GRB2, NCK), their binding partners (e.g., phosphorylated LAT, N-WASP), fluorescently labeled components, physiological buffer with crowding agent (e.g., 5% PEG-8000). Method:

- Prepare reaction mixture: Combine SH2-containing proteins and their binding partners at physiological ratios (e.g., 1-10 µM total protein) in a buffer containing a crowding agent to mimic intracellular conditions [2].

- Induce phase separation: Initiate condensation by adding multivalent phosphorylated scaffolds or adjusting temperature to 37°C.

- Visualize condensates: Use differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy and confocal fluorescence microscopy (if components are labeled).

- Assay dynamics: Perform FRAP by photobleaching a region within condensates and monitoring fluorescence recovery over time to confirm liquid-like properties [26].

- Functional validation: Couple with an activity assay (e.g., phosphorylation or actin polymerization) to confirm enhanced function within condensates.

Key Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms

Diagram 1: SH2 Domains in Membrane Proximal Signaling and Condensation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying SH2 Domain Non-Canonical Functions

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma membrane-mimetic vesicles | Lipid-binding assays | PC:PS:PIP₂ (75:20:5) or PC:PS:PIP₃ mixtures; used in SPR and liposome sedimentation [24]. |

| Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) | Mapping membrane-binding interfaces | Identifies intramolecular contacts and conformational changes; used to study SHIP1 autoinhibition [27]. |

| Supported lipid bilayers (SLBs) | Single-molecule imaging of membrane binding | Platform for TIRF microscopy to quantify SH2 domain membrane binding frequency and dynamics [27]. |

| Fluorescent protein tags (mNeonGreen, mCherry) | Live-cell imaging of localization and condensation | Fused to SH2 domains to visualize plasma membrane targeting and condensate formation in vivo [2] [24]. |

| Crowding agents (PEG-8000, Ficoll) | In vitro phase separation reconstitution | Mimic intracellular crowded environment to promote and stabilize biomolecular condensates [2]. |

| Nonlipidic small-molecule inhibitors | Targeting lipid-protein interactions | Potential therapeutic strategy; e.g., nonlipidic inhibitors of Syk kinase that block its PIP₃-dependent membrane binding [2]. |

Computational and Experimental Arsenal for SH2 Domain Ligand Discovery

This technical support center provides guidance for researchers employing quantitative affinity modeling, specifically the ProBound framework, to study SH2 domain interactions. SH2 domains are protein modules of approximately 100 amino acids that specifically bind to phosphorylated tyrosine (pY) motifs, playing a crucial role in cellular signaling networks [2]. The affinity of an SH2 domain for its pY-containing ligand is highly dependent on the amino acid sequence flanking the phosphotyrosine [6]. Accurately predicting this binding energy is essential for understanding signaling pathways, elucidating the impact of pathogenic mutations, and developing strategies to target these often shallow binding surfaces for therapeutic purposes [6] [2].

ProBound is a computational statistical learning method that transforms Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data from affinity selection experiments into a quantitative model predicting binding free energy [6]. This guide addresses common experimental and computational challenges encountered when applying this powerful technique to SH2 domains.

★ Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential reagents and materials for ProBound experiments on SH2 domains.

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Bacterial Peptide Display System [6] | Genetically encoded system for presenting highly diverse random peptide libraries for affinity selection. |

| Random Phosphopeptide Library [6] | A degenerate library (e.g., with 10⁶–10⁷ sequences) used to comprehensively profile SH2 domain binding specificity. |

| SH2 Domain Profiling Data [6] | Existing binding specificity data for SH2 domains, which can be used for model training and validation. |

| ProBound Software [6] | A statistical learning method for building sequence-to-affinity models from multi-round selection NGS data. |

| Nuclease-free Water [28] | Used to dilute samples to the correct concentration (e.g., ~70 ng/μl) prior to library preparation to prevent issues. |

| Fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) [28] | For accurate DNA concentration measurement immediately before starting the NGS library preparation protocol. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using ProBound over a simple Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) for SH2 domain analysis? While a PSSM classifies sequences as binders or non-binders, ProBound goes further by training an additive model that accurately predicts the binding free energy (ΔΔG) for any peptide sequence within the theoretical space [6]. This provides a quantitative, biophysically interpretable measure of affinity (relative to an optimal sequence) rather than a qualitative score, enabling prediction of novel phosphosite targets and the impact of phosphosite variants on binding [6].

FAQ 2: My NGS data shows inconsistent results. What are some common experimental pitfalls? Common issues that affect NGS data quality include:

- Sample Contamination: Contamination by salts or solvents like phenol can interfere with reactions. Re-purify samples by ethanol precipitation [28].

- Inaccurate DNA Quantification: DNA concentration can drift during storage. Always measure concentration using a fluorometer like Qubit immediately before beginning your protocol [28].

- Over-concentrated gDNA: Excessively concentrated genomic DNA can lead to problems during shearing. Dilute samples to ~70 ng/μl in nuclease-free water prior to fragmentation [28].

FAQ 3: Why is a highly degenerate random peptide library preferred over a proteome-derived library for ProBound modeling? A fully random library allows ProBound to explore the entire theoretical sequence space without bias, which is crucial for training a model that can make accurate predictions across all possible sequences [6]. While proteome-derived libraries are useful, their limited diversity (typically 10³–10⁴ sequences) restricts the model's ability to generalize across the full spectrum of potential ligands [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Model Performance or Inaccurate Affinity Predictions

Problem: The final ProBound model does not accurately predict validated binding affinities.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient Library Diversity | Use a highly complex random peptide library (10⁶–10⁷ sequences) to ensure adequate coverage of the sequence space [6]. |

| Suboptimal Selection Stringency | Either too many or too few selection rounds can skew data. Multi-round selection is required, but excessive rounds can deplete information about low-affinity binders. Optimize the number of selection rounds and the protein concentration used in each round [6]. |

| Low Sequencing Depth | Ensure sufficient NGS sequencing depth to obtain reliable count data for individual sequences, especially after selection rounds where high-affinity sequences are still a minority [6]. |

Issue 2: High Background or Non-Specific Binding in Affinity Selections

Problem: The selection output contains an overabundance of low-affinity binders, making it difficult to identify true high-affinity sequences.

Solution:

- Validate SH2 Domain Integrity: Ensure the expressed SH2 domain is properly folded and functional.

- Include Competitive Elution: Use specific phosphopeptides during the elution step to competitively displace true binders and reduce background from non-specifically bound peptides.

- Troubleshoot Experimental Carry-over: Implement stringent wash steps to minimize carry-over of non-specifically bound peptides between selection rounds. ProBound's computational model is designed to account for some degree of non-specific binding, but minimizing it experimentally yields cleaner data [6].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Generating NGS Data for ProBound with SH2 Domains

This protocol outlines the key steps for profiling SH2 domain binding specificity using bacterial peptide display and NGS.

1. Library Construction and Preparation

- Library Design: Synthesize a degenerate random oligonucleotide library that encodes for peptides of a fixed length, containing a central tyrosine flanked by random amino acids. The theoretical diversity should be between 10⁶ and 10⁷ sequences [6].

- Cloning and Transformation: Clone the library into an appropriate bacterial display vector. Transform the construct into a compatible bacterial host and ensure high transformation efficiency to maintain library diversity.

- Library Validation: Sequence a subset of the library (e.g., via Sanger sequencing) to confirm the correct representation of random regions before proceeding to display.

2. Bacterial Display and Affinity Selection

- Peptide Display: Induce the expression of the peptide library on the surface of the bacteria.

- Enzymatic Phosphorylation: Treat the displayed peptides with a tyrosine kinase (e.g., c-Src) to phosphorylate the central tyrosine residue, creating a library of random phosphopeptides [6].

- Multi-Round Affinity Selection:

- Incubation: Incubate the displayed phosphopeptide library with the immobilized SH2 domain of interest.

- Washing: Perform stringent washes to remove non-specifically bound and unbound cells.

- Elution: Elute the specifically bound cells. This can be done by competition with a known high-affinity ligand or by other means that preserve cell viability.

- Amplification and Repetition: Grow the eluted cells and use them as the input for the next round of selection. Typically, 2-4 rounds of selection are performed to enrich for high-affinity binders [6].

3. Sequencing and Data Processing

- Sample Preparation: After the final selection round, isolate the plasmid DNA from the enriched population and prepare it for NGS.

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Sequence the region encoding the random peptide using a high-throughput NGS platform to obtain millions of sequencing reads.

- Data Quality Control: Process the raw sequencing data to filter out low-quality reads and correct for PCR amplification biases. Align the sequences to a reference to generate count data for each unique peptide sequence in the input and selected populations.

ProBound Computational Analysis Workflow

ProBound Analysis Workflow for SH2 Domain Data

Data Interpretation Standards

Table 2: Key metrics and parameters for evaluating ProBound model quality and output.

| Metric/Parameter | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Binding Affinity (exp(-ΔΔG/RT)) | A quantity between 0 and 1, inversely proportional to the dissociation constant (K_D), where 1 represents the affinity of the optimal sequence [6]. | Used to rank and compare the predicted strength of different peptide ligands for the SH2 domain. |

| Additive Model | The simplest ProBound model assumes that the binding free energy contribution of each amino acid position is independent [6]. | Provides an easily interpretable energy matrix. Model accuracy should be validated with held-out test sequences. |

| Model Validation | The process of testing the model's predictions against experimental affinity measurements not used in training. | A robust model will show a strong correlation between predicted ΔΔG and experimentally measured K_D values across multiple orders of magnitude. |

This guide outlines the core principles and procedures for implementing ProBound and free-energy regression to model SH2 domain binding affinities from NGS data. The provided FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and standard protocols are designed to help researchers overcome common challenges in this domain. For further technical support on specific computational or experimental issues, consult the primary ProBound literature and the developer's documentation [6]. As research into targeting shallow SH2 domain surfaces progresses, these quantitative models will be indispensable for predicting the functional consequences of mutations and designing targeted therapeutic strategies.

Computational Pipelines for Predicting pH-Sensitive and Allosteric Sites

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Pipeline Implementation

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when using computational pipelines to predict pH-sensitive and allosteric sites, with a specific focus on SH2 domain proteins.

FAQ 1: The pipeline predicts a very high number of potential pH-sensitive sites. How can I distinguish biologically relevant hits from false positives?

A high number of hits is common in initial scans. To prioritize results for experimental validation:

- Apply Evolutionary Conservation Filters: Use tools like ConSurf to filter results, focusing on ionizable residues (e.g., Histidine, Glutamic Acid) that are evolutionarily conserved, as these are more likely to be functionally important [29].

- Analyze Structural Context: Manually inspect the 3D protein structure to determine if predicted residues form a continuous network. A cluster of ionizable residues is a stronger indicator of a functional pH-sensing network than a single residue [29] [2].

- Leverage Experimental Data: Cross-reference predictions with existing phosphoproteomics or functional data. A predicted site is more compelling if it is near a known functional region, such as a phosphotyrosine-binding pocket in an SH2 domain [29] [2].

FAQ 2: My computational model for SH2-peptide binding affinity performs poorly on new data. What could be wrong?

Poor generalization often stems from issues with training data or model features.

- Check Training Data Diversity: Ensure the peptide library used for training covers a sufficiently diverse and representative sequence space. Models trained on limited or biased libraries will not perform well [6] [30].

- Validate Feature Selection: Re-evaluate the features used in your model. For SH2 domains, key features often include the amino acids at specific positions relative to the phosphotyrosine (e.g., pY+1, pY+2, pY+3). Using an additive model based on binding free energy (ΔΔG) can improve quantitative predictions [6] [30].

- Inspect for Data Drift: The biochemical properties of your new experimental data (e.g., peptide length, charge) should match the data on which the model was trained. Significant discrepancies can cause performance drops [31].

FAQ 3: The pipeline fails during execution with opaque error messages. What is a systematic way to diagnose the problem?

Complex pipelines can fail for many reasons. Follow a structured isolation approach [32] [33]:

- Isolate the Problem Stage: Determine if the failure occurs during data ingestion, alignment, model training, or output generation. Check the log files for the first occurrence of an error or warning.

- Verify Input Data and Dependencies: Confirm that your input data format matches the pipeline's expectations. A common issue is version incompatibility; ensure all software dependencies (e.g., Python libraries, bioinformatics tools) are the correct versions. Using containerization (e.g., Docker) can prevent dependency conflicts [32] [34].

- Test with a Minimal Dataset: Run the pipeline on a small, known-good subset of your data. This simplifies debugging and confirms the pipeline's core functionality [33].

FAQ 4: How can I validate that a predicted pH-sensitive site is functionally allosteric?

Computational prediction requires experimental validation. A multi-pronged approach is most convincing [29]:

- Constant-pH Molecular Dynamics (CpHMD) Simulations: These simulations can directly visualize how changes in pH alter protein conformation and dynamics, providing evidence for allosteric communication between the predicted pH-sensing site and the protein's active site [29].

- In Vitro Activity Assays: Measure the enzymatic activity (e.g., kinase or phosphatase activity) of the wild-type protein versus a mutant where the predicted pH-sensing residues are altered. Perform these assays across a range of pH values. A abolished or reduced pH-dependent activity in the mutant strongly supports the prediction [29].

- Cellular Functional Assays: In cell-based assays, introduce mutations at the predicted site and measure downstream signaling outputs using techniques like Western blotting to assess the functional impact of disrupting the putative pH sensor [29].

FAQ 5: The pipeline runs successfully, but the results are not reproducible. What are the key factors to check?

Reproducibility is a cornerstone of scientific computing. Focus on:

- Version Control: Document the exact versions of the pipeline code, all software tools, and operating system used. A single version change can alter results [32] [34].

- Parameter Documentation: Record every parameter and configuration setting used for the run. Many pipelines have default settings that may change between versions.

- Data Provenance: Keep a precise record of the input dataset, including its source and any pre-processing steps applied. Ideally, use a data management system that tracks this information automatically.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: In Vitro Validation of pH Sensitivity using Activity Assays

This protocol is used to biochemically validate computational predictions of pH sensitivity for enzymes like SHP2 or SRC [29].

- Protein Purification: Express and purify the wild-type protein and a mutant form where key predicted ionizable residues (e.g., His116 and Glu252 in SHP2) are mutated to alanine or other non-ionizable residues.

- Prepare Assay Buffers: Create a series of buffered solutions covering a physiologically and pathologically relevant pH range (e.g., pH 6.0 to 8.0).

- Perform Kinase/Phosphatase Reaction: Incubate the purified protein with its substrate in the different pH buffers. For a kinase, include ATP; for a phosphatase, provide a phosphorylated substrate.

- Quantify Activity: Measure the initial reaction rate for each pH condition. For kinases, this could involve quantifying ADP production or substrate phosphorylation. For phosphatases, measure phosphate release.

- Data Analysis: Plot enzyme activity (Vmax or kcat/Km) versus pH. A significant shift in the pH-activity profile between the wild-type and mutant protein confirms the functional role of the mutated residues in pH sensing.

Protocol 2: Building a Sequence-to-Affinity Model for SH2 Domains

This protocol details the integrated computational and experimental workflow for quantitatively predicting SH2 domain binding affinities [6] [30].

- Library Construction: Generate a highly diverse library of random phosphopeptides (complexity of 10^6–10^7 sequences) using bacterial peptide display.

- Affinity Selection: Express the SH2 domain of interest and perform multiple rounds of affinity-based selection against the peptide library.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Sequence the input library and the peptides enriched after each selection round using NGS.

- Free-Energy Regression with ProBound: Input the NGS count data into the ProBound computational framework. The algorithm learns an additive model that predicts the binding free energy (ΔΔG) for any peptide sequence in the theoretical space.

- Model Validation: The trained model can be used to predict novel binding partners from the phosphoproteome or assess the impact of single-point mutations in known binding sites on affinity.

The following tables consolidate key quantitative findings from recent research on SH2 domains and pH-sensing.

Table 1: Characteristics of Validated pH-Sensing Residues in SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins

| Protein | Identified pH-Sensing Residues | Experimental System | Key Functional Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHP2 | His116, Glu252 [29] | In vitro phosphatase assay & cellular signaling | Abolished pH-sensitive activity when mutated [29] |

| SRC | Network of ionizable residues (specific mutations not listed) [29] | In vitro kinase assay & constant-pH MD simulations | pH-sensitive regulation functions alongside phosphorylation [29] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of SH2 Domain Binding Affinity Models

| Modeling Approach | Key Input Data | Output | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProBound with Free-Energy Regression [6] [30] | NGS data from multi-round affinity selection on random peptide libraries | Quantitative prediction of binding free energy (ΔΔG) | Predict novel phosphosite targets; impact of phosphosite variants [6] |

| Traditional Position-Specific Scoring Matrix (PSSM) | Affinity data for a limited set of peptides | Classification of binders vs. non-binders | Rapid scanning for potential binding sites [6] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|

| Random Peptide Library | A highly diverse, genetically encoded library of peptides (e.g., 10^7 sequences) for bacterial display. | Profiling the sequence specificity of SH2 domains or other peptide-binding domains [6]. |

| ProBound Software | A statistical learning method for building quantitative sequence-to-affinity models from NGS data. | Transforming peptide display data into predictive models of binding free energy [6] [30]. |

| Constant-pH Molecular Dynamics (CpHMD) | A specialized simulation method that allows protonation states of ionizable residues to change dynamically with pH. | Studying the molecular mechanism of pH-dependent allostery and validating predicted pH-sensing networks [29]. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The following diagrams illustrate the core computational and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Diagram 1: pH-Sensitive Site Prediction Pipeline

Diagram 2: SH2 Domain Affinity Profiling

Diagram 3: SH2 Domain Signaling Context

Understanding the recognition specificity of SH2 domains is fundamental to decoding cellular signaling networks and developing therapeutic strategies for pathologies arising from their dysregulation [5]. These domains function as critical "readers" of phosphotyrosine (pTyr) signaling, with human cells containing approximately 120 SH2 domains across 110 proteins that modulate signal transduction by binding to short peptides containing phosphorylated tyrosines [8] [5]. High-throughput profiling technologies have emerged as powerful tools to comprehensively map these interactions on a proteome-wide scale, enabling researchers to tackle the challenging nature of shallow SH2 domain binding surfaces.

This technical support center provides detailed methodologies, troubleshooting guidance, and strategic insights for implementing two complementary high-throughput approaches—bacterial peptide display and degenerate library screening—to advance research on SH2 domain binding specificity. These methodologies enable the quantitative description of sequence specificity needed to predict signaling pathways and design sequences for biomedical applications [35] [36].

Core Methodologies and Technical Approaches

Bacterial Peptide Display Platform

The bacterial peptide display platform combines genetically encoded peptide libraries displayed on the surface of E. coli cells with deep sequencing to quantitatively profile sequence recognition by SH2 domains [35] [36]. The methodology involves displaying peptide libraries as fusions to the engineered bacterial surface-display protein eCPX, followed by binding with purified SH2 domains, magnetic bead-based separation using biotinylated bait proteins and avidin-functionalized magnetic beads, and deep sequencing analysis to determine binding affinities across the library [36].

Key Workflow Steps:

- Library Transformation: Introduce genetically encoded peptide library into E. coli cells for surface display

- Peptide Display: Express peptide-eCPX fusions on bacterial surface

- SH2 Domain Binding: Incubate displayed library with purified SH2 domains

- Magnetic Separation: Islect bound cells using biotinylated bait proteins and avidin-functionalized magnetic beads

- Sequencing & Analysis: Amplify and sequence DNA from selected cells to determine enrichment scores

Degenerate Peptide Library Screening

Degenerate peptide library approaches investigate SH2 domain specificity using synthetic peptide libraries with a central phosphorylated tyrosine residue [8] [37]. The oriented peptide library method, originally pioneered for SH2 domain characterization, presents libraries where fixed positions flanking the central pTyr enable systematic determination of position-specific amino acid preferences [8] [38]. Recent advancements include high-density peptide chip technology containing nearly the full complement of tyrosine phosphopeptides in the human proteome, allowing probing of SH2 domain affinity against thousands of potential binding partners simultaneously [8].

Table: Comparison of High-Throughput Profiling Approaches

| Parameter | Bacterial Peptide Display | Degenerate Library Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Library Diversity | 10⁶-10⁷ unique sequences [35] | Hundreds to thousands of predefined sequences [8] |

| Throughput | High (magnetic bead processing of multiple samples) [36] | Moderate to High (depends on platform) [8] |

| Quantitative Output | Relative binding affinities from enrichment scores [36] | Binding intensity measurements (Z-scores, fluorescence) [8] |

| Key Advantage | Customizable libraries for specific questions [35] | Direct profiling of human proteome-derived peptides [8] |

| Equipment Needs | Deep sequencing capability, magnetic separation [36] | Peptide synthesis/screening platform, detection system [8] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common Issues in High-Throughput SH2 Profiling

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Library Yield | Poor input quality, contaminants, inaccurate quantification [39] | Re-purify input samples; use fluorometric quantification (Qubit) instead of UV absorbance; verify pipette calibration [39] |

| High Background Binding | Non-specific SH2 domain interactions; insufficient washing [37] | Optimize binding buffer conditions (salt concentration, detergent); increase wash stringency; include control domains [37] |

| Poor Library Diversity | Over-amplification; inefficient transformation [39] | Limit PCR cycles; use high-efficiency transformation protocols; assess library complexity by sequencing before selection [39] |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Technical variation in binding or separation steps [8] | Standardize incubation times and temperatures; use master mixes for reagents; implement robotic liquid handling [8] [39] |

| Weak or No Binding Signal | Protein stability issues; incorrect peptide presentation [37] | Verify SH2 domain folding and activity; check display system functionality; confirm phosphorylation status of peptides [37] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What library design is most appropriate for comprehensively profiling SH2 domain specificity? A: For initial characterization, the X5-pY-X5 random library provides unbiased determination of sequence preferences. For disease-focused studies, proteome-derived libraries containing known phosphorylation sites with natural variants are more relevant [35] [36]. The optimal approach often involves using both sequentially to first define the binding motif and then test against physiological sequences.

Q: How can I validate interactions identified through high-throughput screening? A: Orthogonal validation methods are essential. Fluorescence polarization assays provide quantitative binding affinities for individual peptides [37]. Co-immunoprecipitation or pull-down assays in cellular contexts can confirm physiological relevance, and structural approaches like X-ray crystallography or NMR can elucidate binding mechanisms [4] [10].

Q: What controls should be included in SH2 domain binding experiments? A: Essential controls include: (1) Non-phosphorylated peptide library to assess phosphorylation dependence; (2) SH2 domains with point mutations in the FLVR motif (e.g., R→K) to verify phosphotyrosine-specific binding [10]; (3) Known strong and weak binding peptides as benchmarks; (4) Unrelated SH2 domains to detect non-specific interactions.

Q: How can I address the challenge of shallow binding surfaces in SH2 domains? A: Focus on extended binding interfaces beyond the canonical pY and +3 pockets. The EF and BG loops that connect secondary structure elements can encode diverse specificities and offer targeting opportunities [4]. Consider screening libraries with longer flanking sequences (-6 to +6 positions) to capture these extended interfaces [10].

Experimental Protocols

Bacterial Peptide Display for SH2 Domain Profiling

Materials Required:

- eCPX bacterial display system [36]

- Genetically encoded peptide library (X5-Y-X5 or proteome-derived) [35]

- Purified SH2 domain (GST-tagged recommended) [37]

- Biotinylated pan-phosphotyrosine antibody [36]

- Avidin-functionalized magnetic beads [36]

- Deep sequencing platform (Illumina) [35]

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Library Preparation: Transform the peptide library into the eCPX display system and culture under appropriate selection conditions.

- Induction: Induce peptide display with appropriate inducer (e.g., 0.2% arabinose for eCPX) at mid-log phase.

- Binding Reaction: Incubate displayed library (10⁸-10⁹ cells) with purified SH2 domain (100-500 nM) in binding buffer (PBS with 0.1-0.5% BSA, 0.1% NP-40) for 30-60 minutes at room temperature with gentle mixing.

- Magnetic Separation: Add biotinylated pan-pTyr antibody (1:1000 dilution), incubate 20 minutes, then add avidin-functionalized magnetic beads. Capture bound cells using a magnet.

- Washing: Wash beads 3-5 times with binding buffer to remove non-specific binders.

- Elution and Sequencing: Elute bound cells, recover plasmid DNA, and prepare libraries for deep sequencing.

- Data Analysis: Calculate enrichment scores for each peptide by comparing frequency after selection to initial library frequency.

Degenerate Peptide Library Screening Protocol

Materials Required:

- SPOT synthesis membrane or peptide microarray [8]

- Phosphotyrosine-oriented peptide library [8] [37]

- GST-tagged SH2 domains [8]

- Anti-GST fluorescent antibody [8] [37]

- Fluorescence scanner or plate reader [8]

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Library Synthesis: Generate peptide library using SPOT synthesis or microarray printing technology. Include control peptides with known binding properties.

- Blocking: Incubate membrane/chip with blocking buffer (5% BSA in TBST) for 1 hour.

- Probing: Incubate with GST-tagged SH2 domain (1-10 μg/mL) in binding buffer for 2 hours.

- Detection: Wash to remove unbound protein, then incubate with anti-GST fluorescent antibody (1:4000 dilution) for 1 hour.

- Imaging: Scan membrane/chip using appropriate fluorescence detection system.

- Data Analysis: Normalize signals, calculate Z-scores, and generate sequence logos from high-binding peptides.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SH2 Domain Profiling

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Display Systems | eCPX bacterial display [36] | Peptide library presentation | Provides high valency display; compatible with FACS and magnetic separation |

| Library Types | X5-Y-X5 random library; pTyr-Var proteomic library [35] | Determinining specificity; assessing natural variants | pTyr-Var library contains ~3000 human phosphosites + ~5000 variants |

| Detection Reagents | Biotinylated pan-pTyr antibodies; Anti-GST antibodies [36] [37] | Detection of SH2-bound phosphorylated peptides | Fluorescent or magnetic conjugates for different detection modalities |

| Separation Systems | Avidin-functionalized magnetic beads [36] | Isolation of SH2-bound peptides | Enable benchtop processing of multiple samples simultaneously |

| Expression Constructs | GST-tagged SH2 domains [8] [37] | Production of recombinant SH2 domains | GST tag facilitates purification and detection |

| Binding Assay Tools | Fluorescence polarization reagents [37] | Validation of individual interactions | Provides quantitative Kd measurements for hit confirmation |

Visualization of Methodologies and Binding Relationships

Bacterial Peptide Display Workflow

SH2 Domain Binding Mechanism

Strategic Applications for SH2 Domain Research

The integration of bacterial peptide display and degenerate library screening provides complementary advantages for targeting shallow SH2 domain binding surfaces. Bacterial display offers unparalleled diversity for discovering novel binding motifs, while degenerate libraries enable focused investigation of proteome-relevant sequences. Together, these methods facilitate:

Comprehensive Specificity Mapping: Identify key residues beyond the canonical pY+3 motif that contribute to binding affinity and selectivity, including the role of negative selection in shaping recognition specificity [35].

Impact of Genetic Variation: Profile the effects of disease-associated mutations and natural polymorphisms on SH2 domain interactions using variant libraries, revealing phosphosite-proximal mutations that significantly impact recognition [36].

Rational Design of Inhibitors: Develop peptidomimetics and competitive inhibitors by identifying high-affinity binding sequences that can be optimized for specificity and stability [37].

Network Biology Insights: Construct probabilistic SH2-mediated interaction networks by integrating high-throughput binding data with orthogonal context-specific information, advancing systems-level understanding of tyrosine phosphorylation signaling [8].

These approaches are particularly valuable for addressing the challenging nature of shallow SH2 domain binding surfaces by enabling systematic exploration of extended interfaces and the contribution of multiple weak interactions to overall binding affinity. The structural flexibility observed in SH2 domain surface loops [4] further highlights the importance of comprehensive profiling to capture the full spectrum of binding possibilities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the non-canonical functions of SH2 domains beyond phosphotyrosine (pY) binding? SH2 domains are not limited to pY recognition. A significant non-canonical function is their interaction with membrane lipids. Research indicates that nearly 75% of SH2 domains can interact with lipid molecules, particularly phosphoinositides like PIP2 and PIP3 [2]. These interactions are crucial for membrane recruitment and the regulation of catalytic or scaffolding functions of SH2-containing proteins [2].

- Troubleshooting Guide: Investigating SH2-Lipid Interactions

- Problem: Inconsistent binding data in lipid interaction assays.

- Potential Cause: The presence of a functional pY-binding pocket may be competing with or influencing the lipid-binding event.

- Solution: Characterize the two binding sites independently. Use site-directed mutagenesis to create mutants that are deficient in pY-binding (e.g., mutate the critical arginine in the FLVR motif) or lipid-binding (see FAQ 2) to isolate their individual contributions [40].

- Problem: Poor protein-membrane association in cellular studies.

- Potential Cause: The lipid-binding pocket may be disrupted, or the specific lipid moiety may not be present in the experimental system.

- Solution: Verify the lipid composition of your cellular or in vitro system. Utilize surface plasmon resonance (SPR) with artificial lipid bilayers containing specific phosphoinositides to quantitatively measure binding affinity and specificity [40].

- Problem: Inconsistent binding data in lipid interaction assays.

FAQ 2: Which specific residues in SH2 domains are critical for lipid binding, and how can I study them? Lipid-binding pockets in SH2 domains are often distinct from the pY-binding pocket. They are typically characterized by the presence of basic (positively charged) residues, such as lysine (Lys or K), flanked by hydrophobic amino acids [2]. For example, in the C1-Ten/Tensin2 SH2 domain, three basic residues were identified as critical for high-affinity binding to PIP3 [40].

- Troubleshooting Guide: Mutagenesis of Lipid-Binding Pockets

- Problem: A lipid-binding site mutant shows unexpected protein instability.

- Potential Cause: The introduced mutation disrupts the structural integrity of the SH2 domain fold.

- Solution: Always check the protein expression level and solubility. Perform circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy or similar assays to confirm that the mutant retains a properly folded structure.

- Problem: A mutant designed to abolish lipid binding also loses pY-peptide binding.

- Potential Cause: The mutated residue might be involved in stabilizing the overall SH2 domain structure, or the lipid and pY pockets may be allosterically linked.

- Solution: Map the mutated residue onto a 3D structure of the SH2 domain. If it is not part of the canonical pY pocket, perform functional assays to test for allosteric effects.

- Problem: A lipid-binding site mutant shows unexpected protein instability.

FAQ 3: What experimental strategies can be used to target the shallow lipid-binding pockets of SH2 domains? Targeting these dynamic and hydrophobic pockets requires a combination of computational and experimental approaches. Homology modeling and induced-fit docking can predict ligand-binding poses within the pocket [41]. Furthermore, bacterial peptide display coupled with next-generation sequencing (NGS) and computational analysis using tools like ProBound can profile binding specificities and help build quantitative sequence-to-affinity models, even for weak interactions [6].

- Troubleshooting Guide: Targeting Shallow Pockets

- Problem: Small molecules designed for the lipid pocket show low binding affinity.

- Potential Cause: The compounds may not adequately address the pocket's hydrophobicity or dynamic nature.

- Solution: Focus on designing or screening for compounds with hydrophobic moieties. Consider covalent inhibitors that can form stable bonds with cysteine or other residues in the pocket [42].

- Problem: Difficulty in expressing and purifying full-length SH2-containing proteins for structural studies.

- Potential Cause: Multi-domain proteins can be unstable or insoluble.

- Solution: Express the SH2 domain as an isolated module. Protocols for the expression and production of recombinant SH2 domain proteins are well-established and can be adapted for structural and biophysical analyses [43].

- Problem: Small molecules designed for the lipid pocket show low binding affinity.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Identifying Critical Lipid-Binding Residues via Site-Directed Mutagenesis and SPR

This protocol is adapted from studies on the C1-Ten/Tensin2 SH2 domain [40].

1. Hypothesis and Computational Prediction:

- Objective: Identify residues critical for PIP3 binding.

- Method: Use homology modeling and docking of the lipid ligand (e.g., 14,15-EET for GPCRs) to the SH2 domain structure to predict the binding pocket [41]. Look for a cluster of basic and hydrophobic residues.

2. Mutagenesis:

- Reagents: Wild-type SH2 domain plasmid (e.g., in pRSET-B vector with an N-terminal His6 tag for purification).

- Method: Use a site-directed mutagenesis kit (e.g., QuickChange) to generate point mutations, converting basic residues (Lys, Arg) to alanine or other neutral residues [40].

- Example: Generate mutants K1134A, R1154A, and K1187A for the C1-Ten SH2 domain [40].

3. Protein Expression and Purification:

- Expression System: E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS.

- Purification: Utilize the His6 tag for purification via nickel-affinity chromatography, followed by size-exclusion chromatography to ensure monodispersity [40].

4. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Binding Assay:

- Sensor Chip: Use a chip suitable for liposome capture (e.g., L1 chip).

- Liposome Preparation: Create liposomes composed of POPC:POPS (e.g., 80:15 molar ratio) with or without 5% of the target lipid (e.g., PIP3). Include control lipids (e.g., PIP2) [40].

- Binding Analysis:

- Immobilize liposomes on the sensor chip.

- Inject purified wild-type and mutant SH2 domains at a range of concentrations.

- Record sensorgrams and determine the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

- Interpretation: A significant increase in KD (weaker binding) for a mutant compared to wild-type indicates the residue is critical for lipid interaction [40].

Protocol: Bacterial Display and NGS for Profiling SH2 Specificity

This protocol outlines the integrated experimental-computational workflow for building quantitative affinity models [6].

1. Library Construction:

- Create a highly diverse, random peptide library displayed on the surface of bacteria. The library should be genetically encoded to allow for NGS linkage [6].

2. Affinity Selection:

- Incubate the bacterial display library with the purified SH2 domain of interest.

- Use enzymatic phosphorylation (if necessary) to generate phosphotyrosine in the displayed peptides [6].

- Perform multiple rounds of affinity-based selection to enrich for high-affinity binders. The number of rounds is critical to retain information on low-affinity sequences [6].

3. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS):

- Isolate DNA from the input library and from populations after each selection round.

- Perform NGS to obtain millions of sequence reads, tabulating the count for each peptide sequence in each sample [6].

4. Computational Analysis with ProBound:

- Use the ProBound software framework to analyze the multi-round NGS data.

- ProBound uses a free-energy regression model to account for library complexity, selection biases, and non-specific binding.

- Output: The software generates an additive model that predicts the relative binding free energy (∆∆G) for any peptide sequence within the theoretical space, providing a quantitative sequence-to-affinity map [6].