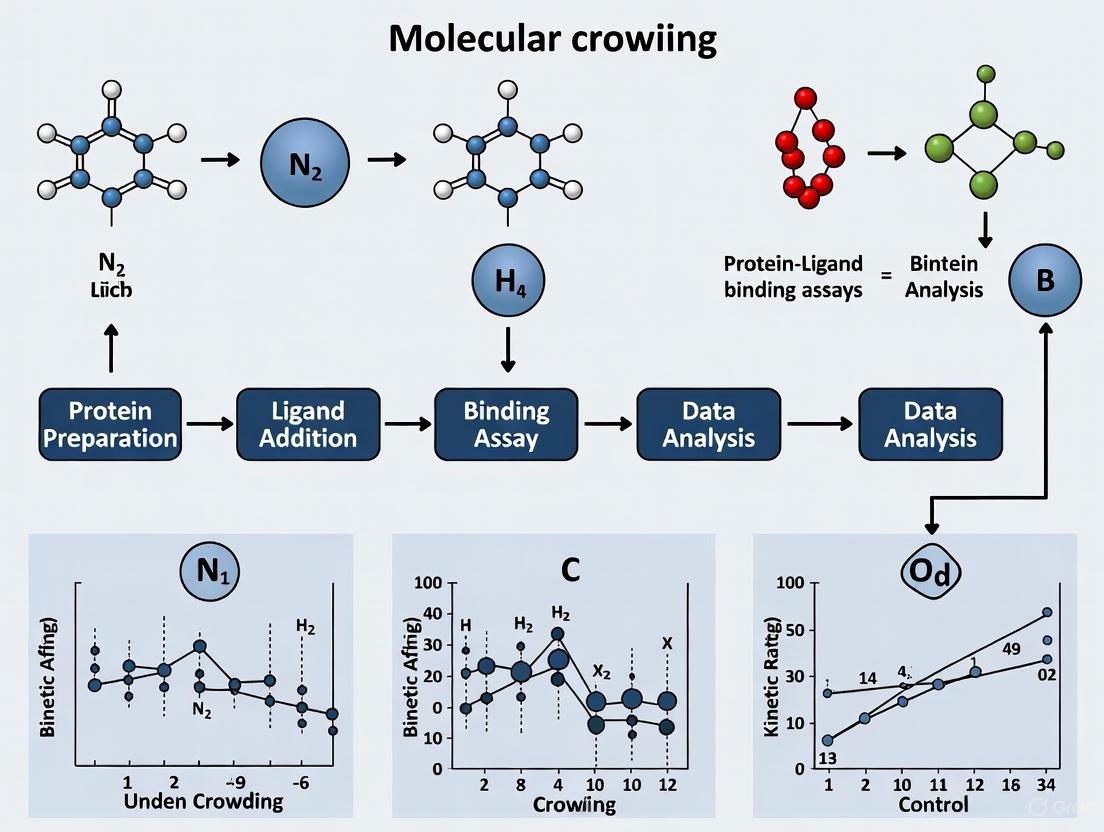

Beyond Dilute Solutions: A Practical Guide to Correcting for Molecular Crowding in Protein-Ligand Binding Assays

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with the significant effects of molecular crowding on protein-ligand interactions.

Beyond Dilute Solutions: A Practical Guide to Correcting for Molecular Crowding in Protein-Ligand Binding Assays

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with the significant effects of molecular crowding on protein-ligand interactions. It first establishes the foundational principles, explaining how crowded intracellular environments, with macromolecule concentrations reaching 400 g/L, fundamentally alter binding kinetics and equilibria compared to standard dilute in vitro assays. The guide then details current methodological approaches, from experimental techniques using crowding agents to advanced computational docking and deep learning models like AlphaFold3 that aim to incorporate flexibility. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses common pitfalls, including the non-trivial role of crowder chemistry and the challenge of accounting for protein conformational changes. Finally, the article covers validation strategies, benchmarking the performance of traditional and AI-based methods against experimental data and discussing the path toward more physiologically relevant and predictive binding assays for drug discovery.

The Crowded Cell: Why Dilute Solution Assays Fail to Predict True Binding Behavior

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is molecular crowding, and why is it critical for in vitro binding assays?

Molecular crowding refers to the influence of a solution containing a high total concentration of macromolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, polysaccharides) on the properties and reactions of any single macromolecule within that solution [1]. The intracellular environment is densely packed, with macromolecule concentrations in E. coli, for example, estimated at 300–400 g/L [2] [1]. In such a crowded milieu, a significant proportion (up to 30-40%) of the total volume is physically occupied by these macromolecules, making it unavailable to other molecules. This is termed the excluded volume effect [3] [1]. When biochemical assays are performed in dilute, ideal solutions in the test tube, they fail to replicate these native crowded conditions, which can lead to results that are orders of magnitude different from those occurring in living cells [1]. For protein-ligand binding studies, correcting for crowding is therefore not optional; it is essential for obtaining biologically relevant data.

What are the fundamental differences between "Excluded Volume" and "Soft Interactions"?

The excluded volume effect is just one component of the total influence of a crowded environment. The combined effects are traditionally divided into two categories [3] [4]:

- Excluded Volume (Hard Interactions/Repulsions): This is a purely steric, entropic phenomenon. Crowder molecules, modeled as inert, hard objects, reduce the volume of solvent available to a "test" protein or a protein-ligand complex. This reduction in available space increases the effective concentration (chemical activity) of all macromolecular species, favoring more compact states and associations. Excluded volume generally stabilizes folded proteins and promotes protein-ligand binding [3] [4] [1].

- Soft Interactions (Chemical Interactions): These are weak, non-covalent, and often non-specific chemical interactions (e.g., electrostatic, hydrophobic, van der Waals) between the crowder molecules and the test protein. Unlike hard interactions, soft interactions can be either attractive or repulsive. Consequently, they can either destabilize or stabilize a protein's native structure and can either inhibit or promote ligand binding, depending on their nature [3] [4].

The following diagram illustrates how these competing forces influence a protein's conformational equilibrium and its ability to bind a ligand.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

My protein-ligand binding affinity measured in crowded conditions is lower than in dilute buffer. I thought crowding was supposed to promote binding. What is happening?

This is a common issue and often points to the dominance of destabilizing soft interactions. While the excluded volume effect does promote association, attractive soft interactions between the crowder and your protein can destabilize the protein's native structure, making it less competent for ligand binding [3] [4]. To troubleshoot:

- Check the size of your crowding agent: Smaller crowders (e.g., PEG 10 kDa) are more likely to penetrate the protein's hydration shell and engage in destabilizing soft interactions. Larger crowders (e.g., Ficoll 70, PEG 20 kDa) exert a stronger excluded volume effect with fewer soft interactions [4].

- Check the chemical nature of your crowder: Ensure the crowder is relatively inert for your system. For example, if your protein is negatively charged, using a negatively charged crowder like heparin will create repulsive soft interactions that enhance the excluded volume effect. Using a positively charged crowder could cause attractive, non-specific binding.

- Verify protein stability: Use techniques like circular dichroism (CD) or differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) to confirm that your crowding agent is not denaturing your protein under assay conditions.

My results with different crowding agents are inconsistent. How do I choose the right one?

The choice of crowding agent is critical and depends on your experimental goal. Different crowders have different propensities for excluded volume versus soft interactions. The table below summarizes the effects of common crowding agents based on empirical studies.

Table 1: Effects of Common Macromolecular Crowding Agents

| Crowding Agent | Typical Size | Primary Mechanism | Observed Effect on Protein/Ligand System | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | ~70 kDa | Predominantly Excluded Volume | Strong stabilization of native state; promotes binding [4]. | Often considered a "steric" crowder; less prone to specific soft interactions. |

| PEG 20,000 | ~20 kDa | Mixed (Excluded Volume leaning) | Stabilizing effect on cytochrome c structure [4]. | Larger size favors volume exclusion over chemical interactions. |

| PEG 10,000 | ~10 kDa | Mixed (Soft Interaction leaning) | Perturbation of cytochrome c structure; can induce molten globule state [4]. | Small enough to engage in significant soft interactions. |

| Dextran | Varies | Mixed | Varies significantly with size and charge; can be stabilizing or destabilizing. | Highly variable; requires careful characterization for your specific system. |

| Serum Albumin | ~66 kDa | Mixed (Significant Soft Interactions) | Can mimic cytoplasmic complexity but high risk of non-specific interactions. | Not inert; can participate in specific and non-specific binding. |

How can I experimentally decouple the contributions of excluded volume and soft interactions in my binding assay?

A systematic approach is required to disentangle these effects. The workflow below outlines a robust experimental strategy.

Detailed Protocol for Step 2: Size-Dependent Crowding Analysis

This protocol is adapted from studies on cytochrome c, which effectively discriminated the effects of PEG 10 kDa vs. PEG 20 kDa [4].

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare identical samples of your protein (e.g., at 5-10 µM) in your standard assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- Into separate aliquots, add increasing concentrations (e.g., 50, 100, 150, 200 mg/mL) of two different-sized crowders, such as PEG 10 kDa and PEG 20 kDa. Ensure a control sample with no crowder.

- Filter all solutions through a 0.22 µm membrane to remove aggregates.

- Binding Affinity Measurement:

- Use a technique suitable for crowded solutions, such as Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) or a Fluorescence Anisotropy-based assay if the ligand is fluorescent.

- Perform the binding experiment at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) for all samples.

- Data Interpretation:

- If the larger crowder (PEG 20k) enhances binding affinity more than the smaller one (PEG 10k), the excluded volume effect is dominant.

- If the smaller crowder (PEG 10k) weakens binding affinity or has a much smaller effect, it indicates that soft interactions are counteracting the excluded volume benefit.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Crowding in Binding Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | An inert polysaccharide used to simulate steric excluded volume effects with minimal soft interactions. | Excellent first choice for probing pure excluded volume. High solubility and low charge. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A versatile polymer crowder; effect is highly size-dependent. | Small PEGs (≤10 kDa) probe soft interactions; large PEGs (≥20 kDa) are better for volume exclusion. Can be hydroscopic. |

| Dextran | A branched polysaccharide crowder available in a range of molecular weights. | Like PEG, effects are size-dependent. Can have variable charge; source and grade are important. |

| Guanidinium Chloride (GdmCl) | A chemical denaturant used in stability assays to measure free energy changes (ΔG) under crowded conditions. | Used to determine if crowders stabilize or destabilize the protein's native fold [4]. |

| Syringe Filters (0.22 µm) | For clarifying crowded solutions to remove particulate matter and pre-formed aggregates. | Essential for preventing artifacts in spectroscopic measurements and clogging of instrument flow cells. |

| Dialysis Membranes | For exchanging buffers and removing excess salts after protein oxidation or other modifications. | Ensure the molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) is appropriate for your protein and that crowders do not adhere to the membrane. |

Advanced Applications and Best Practices

How can I account for crowding in computational drug design and affinity prediction?

The field of computational affinity prediction is rapidly evolving with deep-learning models, but most are trained on structural data from dilute conditions [5] [6]. To enhance predictions for crowded cellular environments:

- Physics-Based Corrections: After obtaining a binding affinity prediction from a model like AK-score or a docking program, apply a post-hoc correction based on the excluded volume theory, which favors the associated state (complex) over the dissociated state (protein + ligand) [5].

- Explicit-Solvent Simulations: When using Molecular Dynamics (MD) with methods like MM-GBSA/PBSA, include explicit crowder molecules in the simulation box. This is computationally demanding but can directly capture both excluded volume and soft interactions [5].

- Awareness of Limitations: Understand that state-of-the-art models like 3D-Convolutional Neural Networks (3D-CNNs), while achieving high correlation with experimental data (Pearson R up to ~0.83), are still benchmarks on data from dilute environments and may not extrapolate to crowded in vivo conditions [5] [6].

What are the best practices for designing a binding assay under crowded conditions?

- Start with Inert Crowders: Begin your investigation with Ficoll 70 or a similar large, inert polymer to establish a baseline for the excluded volume effect.

- Use a Panel of Crowders: Never rely on a single crowder. Use a panel of agents with different sizes and chemical properties (e.g., Ficoll 70, PEG 10k, PEG 20k, Dextran 70) to map out the interplay of forces.

- Control for Viscosity: High concentrations of crowders dramatically increase solution viscosity, which can slow down diffusion-limited binding kinetics. Use techniques like ITC (which is less sensitive to viscosity in the final analysis) or include viscosity controls in kinetic assays.

- Measure Protein Stability: Always confirm that your protein remains folded and functional in the presence of the chosen crowder at the experimental concentration. Techniques like Circular Dichroism (CD) or Thermal Shift Assays (DSF) are essential for this [7].

- Report Concentrations Accurately: Report crowder concentrations in both weight/volume (mg/mL) and volume fraction (g/100mL) to allow for accurate comparison between studies and different types of crowders.

The intracellular environment is fundamentally different from the idealized, dilute conditions commonly used in in vitro experiments. Within a living cell, the presence of diverse macromolecules—including proteins, nucleic acids, and polysaccharides—creates a dense, crowded environment. Scientific measurements indicate that macromolecules occupy 20–40% of the cell's volume, reaching total concentrations of up to 400 g/L [8] [9]. This crowded milieu significantly impacts biochemical processes by volume exclusion and through various "soft" interactions. For researchers in drug discovery and protein-ligand binding, failing to account for these effects can lead to data that does not accurately reflect a compound's behavior in its biological context. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for incorporating these crucial factors into your experimental workflow.

Key Concepts & Quantitative Data

Core Principles of Macromolecular Crowding (MC)

- Volume Exclusion (Hard Interactions): Crowders reduce the space accessible to a protein. Since the unfolded state occupies more volume than the native state, crowding shifts the equilibrium toward the native, folded structure, thereby increasing thermodynamic stability [8].

- Soft Interactions: These refer to non-covalent, chemical interactions (e.g., electrostatic, hydrophobic) between crowders and the protein. Unlike volume exclusion, which is always stabilizing, soft interactions can be either stabilizing or destabilizing [8].

- Consequences for Binding Assays: Crowding can alter local concentrations, hinder molecular diffusion, and affect protein kinetics, dynamics, and aggregation propensities. This means binding affinities (Kd) and stability (ΔG) measured in dilute buffer may not hold true inside a cell [9].

Quantitative Impact of Crowding on Protein Stability

The table below summarizes experimental data demonstrating the stabilizing effect of macromolecular crowding on the model protein BsCspB.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Stabilization of BsCspB under Crowding Conditions

| Crowding Agent | Concentration (g/L) | Method | Midpoint of Unfolding (CM) | Free Energy of Unfolding (ΔG0) | Change in Free Energy (ΔΔG0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (Dilute) | 0 | 1D 1H NMR | 2.7 M Urea | 8.4 kJ/mol | Baseline [9] |

| Dextran 20 (Dex20) | 120 | 1D 1H NMR | 3.3 M Urea | 9.7 kJ/mol | +1.3 kJ/mol [9] |

| Polyethylene Glycol 1 (PEG1) | 120 | 1D 1H NMR | 3.3 M Urea | 9.8 kJ/mol | +1.4 kJ/mol [9] |

| None (Dilute) | 0 | 19F NMR (4-19F-Phe-BsCspB) | - | 8.7 ± 0.2 kJ/mol | Baseline [8] |

| Cell Lysate | Increasing | 19F NMR | - | Increased monotonically | Stability increased with lysate concentration [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Crowding Studies

| Item | Function & Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Crowders (PEG, Dextran) | Mimic the excluded volume effect of the cellular environment in a controlled, reproducible in vitro system. PEG is less polar, while Dextran is a globular sugar polymer [9]. | Bottom-up approach for systematic studies on protein stability and folding. |

| Cell Lysate | Provides a complex, biologically relevant crowding environment containing a diverse mixture of macromolecules present in the cell [8]. | Top-down approach to study protein behavior in a near-physiological environment. |

| Fluorinated Amino Acids | (e.g., 5-19F-Trp, 4-19F-Phe). Incorporated into proteins for 19F NMR studies. Fluorine is naturally absent from proteins, providing a clean, sensitive signal in complex mixtures [8]. | Site-specific probing of protein stability and dynamics in cell lysate or crowded solutions. |

| Chemical Denaturants | (e.g., Urea). Used to induce reversible folding-to-unfolding transitions, allowing for the determination of a protein's thermodynamic stability (ΔG0) [8] [9]. | Quantifying the increase in protein stability conferred by crowding agents. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (for TSA) | Report on protein thermal unfolding in Thermal Shift Assays (TSA). The dye binds to hydrophobic patches exposed upon unfolding, increasing fluorescence [7]. | High-throughput screening of protein-ligand binding affinities and stability. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Determining Protein Stability via19F NMR in Cell Lysate

This protocol is ideal for quantifying the thermodynamic stability of a protein within a complex, cell-like environment [8].

Protein Labeling and Preparation:

- Recombinant Expression: Incorporate a fluorinated amino acid (e.g., 5-19F-Tryptophan or 4-19F-Phenylalanine) into your target protein via site-directed mutagenesis and expression in a suitable host.

- Purification and Validation: Purify the labeled protein to high homogeneity. Validate that fluorination does not alter the protein's structure or wild-type stability using techniques like 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR and/or circular dichroism [8].

Sample Preparation in Lysate:

- Prepare Lysate: Create a concentrated cell lysate from your model organism (e.g., E. coli).

- Mix Sample: Combine the 19F-labeled protein with the cell lysate at the desired final concentration.

- Urea Titration: Prepare a series of identical protein-lysate samples and introduce a stepwise increase in urea concentration (e.g., from 0 M to 6.3 M) to chemically induce unfolding.

NMR Data Acquisition:

- For each urea concentration in the series, acquire a one-dimensional 19F NMR spectrum.

- Monitor Chemical Shift: As the protein unfolds, the chemical environment of the 19F nucleus changes, leading to a shift in its resonance signal or the appearance of new peaks corresponding to the unfolded state.

Data Analysis and Fitting:

- Plot Transition Curve: For each urea concentration, quantify the signal intensities (or chemical shifts) corresponding to the native (N) and unfolded (U) states.

- Calculate Fraction Unfolded: Plot the fraction of unfolded protein against the urea concentration.

- Determine Thermodynamic Parameters: Fit the resulting sigmoidal curve to a model for a two-state folding transition (e.g., linear extrapolation method) to derive the free energy of unfolding (ΔG0) and the midpoint of denaturation (CM) [8] [9].

Workflow for Protein Stability via 19F NMR

Protocol: Binding Affinity Determination by Thermal Shift Assay

Thermal Shift Assay (TSA) is a high-throughput method to estimate protein-ligand binding affinities from a single ligand concentration, useful for screening potential drugs [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare identical samples of your purified protein in a suitable buffer. Include a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) that binds to hydrophobic regions.

- To the experimental samples, add your ligand at a single, fixed concentration. Include a no-ligand control sample.

Thermal Denaturation:

- Load all samples into a real-time PCR instrument or a dedicated thermal shift instrument.

- Run a thermal ramp (e.g., from 25°C to 95°C at a gradual rate of ~1°C/min) while continuously monitoring the fluorescence signal.

Data Collection:

- The fluorescence intensity will increase sharply as the protein unfolds and exposes hydrophobic regions to the dye.

- The instrument software will generate melting curves (fluorescence vs. temperature) for each sample.

Data Analysis:

- Determine the melting temperature (Tm) for each sample, which is the inflection point of the melting curve.

- Calculate the shift in melting temperature (ΔTm) between the ligand-bound sample and the protein-only control.

- Affinity Calculation: Use one of the following methods to estimate the binding affinity (Kd) [7]:

- ZHC Method: Assumes zero heat capacity change (ΔCpL) across small temperature ranges.

- UEC Method: Utilizes the unfolding equilibrium constant derived directly from the melting curve.

- These newer methods (ZHC, UEC) have been shown to outperform conventional curve fitting, especially when the enthalpy of binding is unknown.

Thermal Shift Assay Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: Addressing Common Challenges in Crowding Correction

Q1: My protein aggregates in the presence of high concentrations of synthetic crowders like dextran. How can I mitigate this? A: Aggregation can be a sign of non-specific "soft" interactions. Consider the following:

- Try Alternative Crowders: Switch to a different chemical type of crowder (e.g., from dextran to Ficoll or different molecular weight PEG). The impact of soft interactions is highly dependent on the crowder's properties [8].

- Adjust Buffer Conditions: Slight modifications to ionic strength or pH can sometimes reduce attractive interactions leading to aggregation.

- Validate with a Second Method: If possible, use orthogonal techniques like NMR or analytical ultracentrifugation to confirm that the protein remains monodisperse under your crowding conditions [9].

Q2: I'm observing discrepancies between binding affinities measured in crowded buffers versus in cell lysate. Why? A: This is a common and expected finding. Synthetic crowding agents primarily mimic the excluded volume effect. Cell lysate, however, contains the full complexity of the cytosol, including:

- Specific and Non-specific Soft Interactions: Various biomolecules in the lysate can interact with your protein or ligand in stabilizing or destabilizing ways that synthetic crowders do not replicate [8].

- Cellular Components: The presence of lipids, nucleic acids, or other metabolites in the lysate can directly compete for binding or allosterically modulate your protein's activity.

- Interpretation: Data from synthetic crowders provides a controlled understanding of volume exclusion, while lysate data offers a more biologically realistic, albeit more complex, picture. Both are valuable.

Q3: How do I choose the right concentration for my crowding agent? A:

- For Synthetic Crowders: A common starting point is 100-120 g/L, as this is within the physiologically relevant range and has been used successfully in many studies to demonstrate significant stabilizing effects [9].

- For Cell Lysate: It is informative to perform a concentration-dependent study. Prepare lysate at different dilutions (e.g., equivalent to 50%, 75%, 100% of pellet concentration). A monotonic increase in protein stability with increasing lysate concentration is a key indicator of a crowding effect [8].

Q4: The inner filter effect is skewing my tryptophan fluorescence quenching data. How can I correct for it? A: The inner filter effect occurs when the ligand absorbs light at the excitation or emission wavelengths, artificially reducing the measured fluorescence. To correct for this [10]:

- Perform Control Titrations: Titrate the ligand into a solution that does not contain the protein but has all other buffer components.

- Measure Apparent Fluorescence: Record the "quenching" of fluorescence in this protein-free control.

- Apply Correction: During data analysis, use the values from the control experiment to mathematically correct the fluorescence data from your protein-containing samples.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental molecular mechanisms by which molecular crowding retards association kinetics? Molecular crowding primarily retards association through two key mechanisms:

- Steric Hindrance: High concentrations of macromolecules (crowders) create a physically obstructed environment. This increases the excluded volume, reducing the space available for a ligand and its target to diffuse and encounter each other freely [11]. The diffusing molecules must navigate a more tortuous path, which slows their overall movement [12].

- Reduced Diffusion Rates: Crowding agents directly impede the Brownian motion of molecules. Simulation studies have confirmed that this slowed diffusion extends the time required for a ligand to locate its binding partner, thereby increasing the association time [12].

FAQ 2: How can crowding alter the dissociation rate of a complex? While the direct steric effects of crowding might intuitively suggest that dissociation could also be slowed, the overall effect is more nuanced and is strongly influenced by the post-dissociation state:

- Slowed Rebinding: After dissociation, the same crowders that impede initial association can prevent the dissociated ligand from rapidly diffusing away. This increases the probability of immediate rebinding to the same target, which can be experimentally measured as a slower effective dissociation rate [12].

- Thermodynamic Drive: Crowding creates an excluded volume effect that favors states that minimize the total excluded volume. The bound complex typically occupies less total volume than the two separate partners. This thermodynamic push favors the associated state, which can manifest as a decreased observed dissociation rate [11].

FAQ 3: My binding assay shows a non-monotonic signal as I increase ligand density. Could crowding be the cause? Yes, this is a recognized effect in confined systems like antibody-conjugated nanoparticles. As ligand (e.g., antibody) surface density increases:

- At low coverage, more binding sites are available, leading to increased signal.

- At high coverage, extreme surface crowding occurs. This can lead to steric blocking of binding sites, improper antibody orientation, and significant entropic penalties upon antigen binding, which together cause the capture efficiency (and signal) to plateau or even decrease [13]. The effective affinity is therefore not a fixed value but is determined by the local crowded environment [13].

FAQ 4: How do I determine the correct incubation time for my binding assay to ensure it reaches equilibrium under crowded conditions?

Equilibration is concentration-dependent and is slowest at the lowest concentrations of the limiting component. The time to reach equilibrium is governed by the equation:

kequil = kon [P] + k_off

where [P] is the concentration of the excess binding partner [14]. To establish the correct incubation time:

- Vary Incubation Time: Perform a time-course experiment under your crowded conditions, using the lowest planned concentration of your limiting reactant.

- Reach Plateau: The reaction has reached equilibrium when the measured signal (e.g., complex formation) no longer increases with time [14].

- Use a Conservative Rule: A common standard is to incubate for at least five half-lives of the reaction, which ensures >96% completion [14].

FAQ 5: What are the best-practice controls to confirm that my measured affinity is not an artifact of titration? A critical control is to demonstrate that your measured dissociation constant (K_d) is independent of the concentration of the limiting component.

- Systematic Variation: Set up a series of binding reactions where the concentration of one reactant (e.g., the protein) is held at a low, fixed concentration, while the other (e.g., ligand) is varied across a wide range that brackets the expected K_d [15] [14].

- Check for Consistency: The calculated Kd value should remain constant across this dilution series. If the apparent Kd increases as you lower the concentration of the limiting component, your system is likely in a "titration regime," and the reported affinity is incorrect [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting for Retarded Association

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Validation Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Slow binding kinetics preventing the assay from reaching equilibrium. | 1. High-viscosity crowded environment slowing diffusion. [12]2. Incubation time too short for low-concentration conditions. [14] | 1. Increase incubation time based on a time-course experiment. [14]2. Validate equilibration by demonstrating signal stability over time. [14] |

| Low signal amplitude even after prolonged incubation. | 1. Crowders physically blocking binding sites. [13]2. Ligand/target instability or loss of activity. [16] | 1. Characterize active fraction of your protein. [14]2. Reduce crowder concentration or switch crowder type to minimize non-specific interactions. [11] |

| Inconsistent association rates between replicates. | 1. Inconsistent preparation of crowded medium.2. Inaccurate pipetting of viscous solutions. | 1. Standardize crowder stock solutions and mixing protocols.2. Use positive controls with inert crowders like Ficoll to benchmark performance. [11] |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Addressing Altered Dissociation Kinetics

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Validation Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete dissociation in wash-out experiments. | 1. Slow diffusion of dissociated ligand causes immediate rebinding. [12]2. True dissociation rate (k_off) is very slow. | 1. Add a trap (e.g., unlabeled ligand) to the buffer to capture dissociated molecules and prevent rebinding. [17]2. Extend monitoring time for dissociation to ensure complete curve characterization. [17] |

| Apparent affinity is too high compared to theoretical expectations or dilute measurements. | 1. Excluded volume effect stabilizing the bound complex. [11]2. Rebinding artifact inflating the measured affinity. | 1. Measure true kon and koff kinetically using methods like SPR. [17]2. Report K_d as a range that acknowledges the influence of the crowded environment. [16] |

| Multi-phase dissociation curve. | 1. Heterogeneity in ligand orientation or crowding. [13]2. Presence of multiple binding populations. | 1. Ensure uniform ligand conjugation and surface attachment. [13]2. Use global fitting of kinetic data to a multi-phase model. [17] |

Table 1: Impact of Molecular Crowding on Binding Parameters

Table summarizing simulated and theoretical effects of macromolecular crowding on key kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. [13] [11] [12]

| Parameter | Effect of Crowding (General) | Magnitude / Conditions | Experimental System / Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Association Rate (k_on) | Decreased | Up to an order of magnitude reduction; depends on crowder size and density. [12] | Lattice and off-lattice (ReaDDy) simulations of protein binding. [12] |

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Decreased | Can be reduced by more than half at ~40% volume occupancy. [12] | Langevin dynamics simulations in crowded environments. [12] |

| Dissociation Rate (k_off) | Context-Dependent (Altered) | Can decrease due to excluded volume or rebinding effects. [11] [12] | Theoretical excluded volume models and simulation data. [11] [12] |

| Binding Affinity (K_d) | Context-Dependent (Often Increased) | Non-monotonic behavior observed; depends on surface coverage and ligand size. [13] | Molecular theory of antibody-conjugated nanoparticles (AcNPs). [13] |

| Optimal Surface Coverage | Decreased | Maximum antigen capture at low antibody density; decays at high density due to crowding. [13] | Molecular theory of antibody-conjugated nanoparticles (AcNPs). [13] |

Table 2: Common Macromolecular Crowding Agents and Their Properties

A guide to selecting and using crowding agents in binding assays. [11]

| Crowding Agent | Typical Molecular Mass | Hydrodynamic Radius (Approx.) | Key Properties & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | 70 kDa | 4.0 nm | Spherical, inert sugar polymer; often used to mimic cytoplasmic crowding with minimal viscosity. [11] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | 2 - 35 kDa | 0.4 - 5.7 nm | Flexible polymer; can have specific chemical interactions beyond steric effects. [11] |

| Dextran | 10 - 670 kDa | <1 - 21 nm | Polysaccharide; available in various sizes; can be charged (dextran sulfate). [11] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 66.3 kDa | 3.4 nm | Inert protein crowder; useful for mimicking the complex protein milieu of a cell. [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Equilibration Time for Binding under Crowded Conditions

Purpose: To empirically establish the incubation time required for a binding reaction to reach equilibrium in the presence of crowding agents, ensuring accurate K_d measurement [14].

Materials:

- Purified target protein and ligand

- Selected crowding agent (e.g., Ficoll 70)

- Assay buffer

- Equipment for real-time monitoring (e.g., fluorescence anisotropy-capable plate reader)

Procedure:

- Prepare Reaction Mixtures: Create a series of tubes with a fixed, low concentration of your target protein and ligand concentration near the expected K_d, all prepared in your standard assay buffer containing the desired concentration of crowding agent.

- Initiate Reaction & Monitor: Simultaneously start the reaction (e.g., by adding ligand) and begin continuous or frequent intermittent measurement of the binding signal (e.g., anisotropy).

- Collect Time-Course Data: Record the binding signal at multiple time points, from seconds to several hours, until the signal stabilizes.

- Plot and Analyze: Plot the signal (e.g., fraction bound) versus time. The time required for the signal to reach a stable plateau is the minimum equilibration time.

- Verify at Low Concentration: Confirm that this equilibration time is sufficient for the lowest protein concentration used in your full assay, as equilibration is slowest at low concentrations [14].

Protocol 2: Kinetic Assay to Measure Crowding's Impact on kon and koff

Purpose: To directly quantify the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants of a binding pair in a crowded environment using a real-time method like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [17].

Materials:

- SPR instrument and sensor chip

- Running buffer with and without crowding agent

- Purified, immobilized target protein

- Ligand analyte solution

Procedure:

- Immobilize Target: Covalently immobilize the target protein on the SPR sensor chip using standard amine-coupling or other suitable chemistry.

- Association Phase: Inject ligand analyte solutions at multiple concentrations (spanning a range above and below K_d) over the immobilized target surface. Use a running buffer containing the crowding agent. Monitor the binding response in real-time.

- Dissociation Phase: Switch the flow back to running buffer (with crowding agent) to monitor the dissociation of the complex.

- Reference Subtraction: Subtract the signal from a reference flow cell to account for bulk refractive index changes and non-specific binding.

- Global Fitting: Fit the resulting sensorgrams for all concentrations simultaneously to a 1:1 binding model (or other appropriate model) using the instrument's software to extract kon and koff [17].

- Compare with Dilute Conditions: Repeat the experiment in the absence of crowding agents to directly quantify the kinetic impact of crowding.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Mechanisms of Crowding on Binding Kinetics

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Kinetic Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Crowding Studies

A list of key reagents used to study and correct for molecular crowding in binding assays. [13] [17] [11]

| Reagent / Material | Function in Assay | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | An inert, spherical crowding agent used to mimic the excluded volume effects of the cellular interior without excessive viscosity or specific interactions. [11] | Preferred for its neutral properties. Concentration should be chosen to match desired volume occupancy (e.g., 5-40%). [11] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein-based crowding agent used to create a more biologically relevant crowded milieu, simulating the high protein content of cytoplasm. [11] | Ensure it is purified and free of proteases. Potential for weak, non-specific interactions with some test molecules should be evaluated. [11] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | A label-free technology enabling real-time monitoring of binding kinetics (kon, koff) and affinity (K_d) under various conditions, including crowding. [17] | Ideal for direct kinetic measurements. The immobilization of one binding partner must be optimized to minimize steric issues. [17] |

| Fluorescence Anisotropy / Polarization | A solution-based homogenous assay used to monitor binding events in real-time or at equilibrium, suitable for use in crowded solutions. [14] | Requires a fluorescently labeled ligand. Signal is sensitive to changes in molecular rotation and can be used in time-course experiments. [14] |

| BioSimz / ReaDDy Software | Computational simulation packages used to model and predict the effects of crowding on protein-protein interactions and binding kinetics through Langevin dynamics. [18] [12] | Provides mechanistic insights and can help interpret complex experimental data by simulating association/dissociation in crowded environments. [18] [12] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Crowding Assays

Q1: My binding affinity measurements in crowded conditions are inconsistent. What could be wrong? A: Inconsistency often stems from the chemical properties of your crowding agents, not just their size. The effects of crowding on the dissociation rate constant (koff) are highly dependent on the specific chemistry of the crowder. For instance, a crowded environment may retard the association kinetics (kon) regardless of the crowder used, but the dissociation kinetics can vary in a "non-trivial" way. Ensure you are using multiple types of crowders (e.g., PEG, dextran) and their low molecular weight counterparts (e.g., ethylene glycol, glucose) to distinguish between general excluded volume effects and chemistry-specific interactions [19].

Q2: How can I verify that the protein structure is not altered by the crowding agent? A: Use high-resolution NMR spectroscopy. In a study on cold shock protein B (CspB) bound to ssDNA, researchers confirmed that the structure of the protein-ssDNA complex was fully conserved in crowded environments (300 g/L PEG1 or dextran) by observing that chemical shifts, signal heights, and line widths in 1H–15N HSQC spectra were comparable to those under dilute conditions [19].

Q3: Why is the ssDNA accessibility for my target protein reduced under crowded conditions? A: This can be due to altered dynamics of ssDNA-binding proteins like RPA. Crowding can affect the dynamic binding modes of ssDNA-binding proteins, shifting them towards more protective states with tighter spacing and lower ssDNA accessibility. This process can be facilitated by specific domains, such as the Rfa2 WH domain, and may be counteracted by mediator proteins like Rad52. Investigate if your system involves similar regulatory domains or proteins [20].

Q4: My ligand is binding to new, non-specific sites on the protein in crowded environments. Is this expected? A: Yes, this is a potential dispersion effect. Research on E. coli RNase HI shows that molecular crowding can destabilize primary ligand-binding sites due to the excluded volume effect, leading to an increase in heterogeneous species where ligands bind to additional, minor sites. Fluorescence-based assays combined with multivariate analysis can help identify these alternative binding pathways [21].

Table 1: Impact of Crowding Agents on CspB-dT7 Binding Kinetics [19]

| Crowding Agent | Molecular Weight | Concentration (g/L) | Association (kon) | Dissociation (koff) | Net Effect on Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEG 1 | 1 kDa | 100-300 | Significantly Retarded | Chemistry-Dependent Change | Subtle Change |

| PEG 8 | 8 kDa | 100-300 | Significantly Retarded | Chemistry-Dependent Change | Subtle Change |

| Dextran | 20 kDa | 100-300 | Significantly Retarded | Chemistry-Dependent Change | Subtle Change |

| Ethylene Glycol | Low MW | 100-300 | Significantly Retarded | Chemistry-Dependent Change | Subtle Change |

| Glucose | Low MW | 100-300 | Significantly Retarded | Chemistry-Dependent Change | Subtle Change |

Table 2: Minimal ssDNA Length for Stable RPA Binding [20]

| Number of RPA Molecules | Minimal ssDNA Length (nt) | Preferred Binding Mode |

|---|---|---|

| First RPA | 15 nt | 20-nt or 30-nt mode |

| Second RPA | 40 nt | 20-nt mode (at high RPA conc.) |

| Third RPA | 54 nt | 20-nt mode (at high RPA conc.) |

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Probing ssDNA-Protein Binding in Crowded Environments via Fluorescence Quenching [19]

Objective: To determine the equilibrium affinity and kinetic parameters of ssDNA-protein binding under molecular crowding.

Materials:

- Purified protein (e.g., BsCspB) and ligand (e.g., dT7 ssDNA).

- Crowding agents: PEG (1 kDa, 8 kDa), Dextran (20 kDa), and their monomeric counterparts.

- Stopped-flow fluorescence spectrometer.

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5).

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare solutions of the protein and ssDNA in the desired buffer. Introduce crowding agents at concentrations ranging from 100 to 300 g/L.

- Equilibrium Titration: Perform intrinsic fluorescence quenching experiments. Titrate the ssDNA into the protein solution in the presence and absence of crowders.

- Data Collection for Affinity: Measure fluorescence emission at the relevant wavelength upon each addition. Plot the change in fluorescence versus ssDNA concentration to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD).

- Stopped-Flow Kinetics: Rapidly mix equal volumes of protein and ssDNA solutions using the stopped-flow apparatus, both containing the crowding agent.

- Data Collection for Kinetics: Monitor the fluorescence change over time. Fit the resulting time courses to an appropriate kinetic model to determine the association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants.

Protocol 2: Verifying Structural Integrity with NMR Spectroscopy [19]

Objective: To confirm that the crowded environment does not alter the structure of the protein-ssDNA complex.

Materials:

- 13C/15N isotopically labelled protein.

- High-resolution NMR spectrometer.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare NMR samples of the labelled protein in the absence and presence of crowding agents (e.g., 300 g/L PEG1 or Dex20).

- Titration: Acquire 1H–15N HSQC spectra of the free protein and then upon stepwise addition of ssDNA to a 2:1 molar excess.

- Analysis: Compare the chemical shifts, signal heights, and line widths of the protein backbone and side-chain resonances in crowded versus dilute conditions. The lack of significant perturbations indicates the structure is conserved.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ssDNA-Protein Crowding Studies

| Reagent | Function/Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEG (various MW) | A common polymer crowder to mimic excluded volume effects. | Chemical properties, not just size, influence dissociation kinetics; use different MWs (e.g., 1kDa, 8kDa) [19]. |

| Dextran | A branched polysaccharide crowder; more inert than PEG. | Useful for distinguishing steric effects from chemical interactions [19]. |

| Ficoll | A synthetic, branched sucrose polymer crowder. | Often considered more inert; has a large hydrodynamic radius [11]. |

| Inert Proteins (e.g., BSA) | Protein-based crowders to mimic the intracellular environment more closely. | Risk of specific soft interactions with the protein of interest [11]. |

| Cold Shock Protein B (CspB) | A model ssDNA-binding protein for crowding studies. | Binds 6-7 nt stretches of thymine-based ssDNA; well-characterized structure [19]. |

| Replication Protein A (RPA) | Eukaryotic ssDNA-binding protein for studying accessibility. | Binds dynamically in different modes (20-nt, 30-nt); affected by salt and concentration [20]. |

| Rad52 (Mediator Protein) | Regulates RPA dynamics and Rad51 nucleation on ssDNA. | Can modulate ssDNA accessibility by interacting with RPA [20]. |

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

FAQs: Mechanisms and Crowding Effects

Q1: What are the key mechanistic differences between conformational selection and induced fit?

A1: The distinction lies in the temporal order of conformational changes and binding events [22].

- Induced Fit (IF): The conformational change occurs after the ligand binds. The ligand initially binds to the protein's ground state, forming an intermediate complex, which then relaxes into the final bound state [22].

- Conformational Selection (CS): The conformational change occurs prior to binding. The protein exists in a dynamic equilibrium between at least two conformations. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a higher-energy, pre-existing conformation, shifting the equilibrium [23] [22].

Q2: How does molecular crowding perturb protein-ligand binding assays?

A2: Crowded environments, which mimic the intracellular milieu, can significantly alter binding behavior through several mechanisms [24] [25]:

- Excluded Volume Effects: Crowders reduce the available space, favoring more compact protein states and potentially stabilizing bound complexes [24] [25].

- Non-Specific Interactions: Weak, attractive interactions with crowder molecules can destabilize native protein structures or compete for binding sites [24].

- Altered Binding Pathways: Crowding can shift conformational equilibria and create alternative pathways for ligand binding, for instance, by reducing the effective inhibitor concentration through competitive non-specific binding to other proteins [24] [16].

- Modulated Diffusive Properties: High concentrations of macromolecules slow diffusion and can lead to the formation of transient protein clusters, affecting encounter rates [24].

Q3: My kinetic data shows the observed rate constant (k˅obs) decreasing with increasing ligand concentration. Does this confirm a conformational selection mechanism?

A3: A decreasing k˅obs with increasing ligand concentration has historically been a hallmark of conformational selection [23] [22]. However, caution is required. Under pseudo-first-order conditions (high ligand concentration), an increase in k˅obs can be observed for both induced fit and conformational selection (if the conformational excitation rate is faster than the unbinding rate) [22]. For a definitive distinction, experiments must be performed at a wide range of ligand and protein concentrations. Integrated Global Fit analysis, which combines kinetic data at varied ligand concentrations with equilibrium data, can effectively differentiate the mechanisms without requiring high, potentially problematic, protein concentrations [23].

Q4: What does it mean if my ligand-binding assay is measuring "free" vs. "total" drug, and why does crowding make this important?

A4: This is a critical distinction in pharmacology [16].

- Free Drug: The pharmacologically active fraction that is not bound to any macromolecules and is thus available to engage the target.

- Total Drug: The overall concentration of the drug, including both free and bound forms. Molecular crowding increases the concentration of potential binding partners in the solution. This can shift the equilibrium towards the "bound" state, reducing the "free" drug concentration. Therefore, an assay that measures only "total" drug may overestimate the biologically available concentration in a crowded environment, leading to incorrect PK/PD predictions [16]. Assay conditions (e.g., dilution, reagent concentration) must be carefully characterized to understand which form is being measured [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Binding Affinity Measurements in Concentrated Solutions

Possible Cause: Non-specific interactions between your protein of interest and background crowders are interfering with the specific binding signal [24] [16].

Solutions:

- Implement Control Experiments: Repeat binding experiments with inert, non-interacting crowders like Ficoll or dextran to isolate excluded volume effects from chemical interactions [24] [25].

- Use Orthogonal Methods: Employ a technique like Kinetic Exclusion Assay (KinExA) that directly measures the concentration of free ligand or receptor in a mixture, which can be less susceptible to certain crowding artifacts [26].

- Characterize Reagent Specificity: Ensure your critical assay reagents (e.g., antibodies) are highly specific for the target. The presence of heterophilic antibodies or other interferents can be exacerbated in crowded samples [27].

Problem 2: Uninterpretable or Complex Binding Kinetics in Cellular Lysates

Possible Cause: The complex milieu of the lysate contains multiple components that bind your ligand or alter protein conformation, leading to a superposition of multiple binding events [24] [16].

Solutions:

- Fractionate the Lysate: Simplify the system by fractionating the cellular lysate to identify which component is causing the interference.

- Employ Global Analysis: Use Integrated Global Fit analysis on a complete dataset from kinetics and equilibrium studies, rather than analyzing individual curves. This provides a more robust determination of binding parameters and mechanism under complex conditions [23].

- Validate with Simulations: Perform coarse-grained or atomistic molecular dynamics simulations of your protein in a model crowded environment to gain mechanistic insight and form testable hypotheses about the source of the complex kinetics [24].

Problem 3: Failure to Distinguish Between Induced Fit and Conformational Selection

Possible Cause: The experimental data was likely collected only under pseudo-first-order conditions (ligand concentration >> protein concentration), which can mask the characteristic signatures of the mechanisms [22].

Solutions:

- Vary Protein Concentration Systematically: Design experiments where the total protein concentration is varied over a wide range, including concentrations comparable to or greater than the ligand concentration. This is crucial for revealing the full kinetic behavior [22].

- Analyze the Full Shape of k˅obs vs. [L]₀: Plot the observed rate constant against the total ligand concentration at high protein concentration. Look for symmetry (indicative of Induced Fit) or asymmetry (indicative of Conformational Selection) around the minimum point [22].

- Measure Displacement Kinetics: Incorporate displacement kinetic experiments into a global analysis framework to further constrain the model and improve mechanistic discrimination [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Distinguishing Binding Mechanisms via Chemical Relaxation Kinetics

Objective: To determine whether a protein-ligand binding process follows an induced fit or conformational selection mechanism by analyzing the concentration dependence of the dominant relaxation rate (k˅obs) [23] [22].

Materials:

- Purified protein and ligand.

- Equipment for rapid mixing or temperature jump (e.g., stopped-flow spectrometer).

- Method to monitor binding (e.g., fluorescence, UV-Vis).

Methodology:

- Prepare Solutions: Create a series of solutions with a fixed total protein concentration ([P]₀) that is significant (e.g., > Kd). Vary the total ligand concentration ([L]₀) from values much less than [P]₀ to much greater than [P]₀ [22].

- Initiate Binding: For each concentration pair, rapidly mix the protein and ligand to initiate the binding reaction.

- Monitor Relaxation: Record the signal change over time as the system relaxes to equilibrium.

- Fit Kinetic Traces: Fit the resulting kinetic traces to a multi-exponential model to extract the dominant, slowest relaxation rate, k˅obs [22].

- Global Analysis: Plot k˅obs as a function of [L]₀. Use Integrated Global Fit analysis, combining this kinetic data with independent equilibrium binding data (to determine Kd), to fit the data to equations for both induced fit and conformational selection models [23].

Data Interpretation:

- A symmetric curve of k˅obs vs. [L]₀, with equal values at very low and very high [L]₀, is characteristic of Induced Fit [22].

- An asymmetric curve, where k˅obs at low [L]₀ is significantly larger than at high [L]₀, is characteristic of Conformational Selection [22].

- A monotonically decreasing k˅obs with increasing [L]₀ also indicates Conformational Selection, specifically when the conformational excitation rate (kₑ) is slower than the ligand unbinding rate (k₋) [22].

Protocol 2: Assessing Crowding Effects on Ligand Binding

Objective: To evaluate the impact of molecular crowding on protein-ligand binding affinity and kinetics [24] [25].

Materials:

- Purified protein and ligand.

- Macromolecular crowders (e.g., BSA, Ficoll 70, dextran).

- Equipment for binding assays (e.g., surface plasmon resonance (SPR), isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)).

Methodology:

- Select Crowders: Choose a set of crowders with different properties: "inert" polymers (Ficoll) to probe excluded volume, and proteins (BSA) to probe both volume exclusion and chemical interactions [24].

- Perform Binding Assays: Conduct binding experiments (e.g., saturation binding, kinetic analysis) in the presence of a range of crowder concentrations (e.g., 0-200 mg/mL).

- Compare Parameters: Determine the apparent dissociation constant (Kd,app) and binding kinetics (association rate kon, dissociation rate koff) in the presence and absence of crowders.

- Control for Viscosity: For kinetic measurements, account for the increased solution viscosity due to crowding, which slows diffusion. This allows separation of hydrodynamic effects from specific thermodynamic or kinetic crowding effects.

Data Interpretation:

- A change in Kd,app or k_obs indicates that crowding perturbs the binding process.

- Stabilization (lower Kd,app) by inert crowders suggests a dominant excluded volume effect.

- Destabilization (higher Kd,app) or complex changes in kinetics often point to significant non-specific interactions or altered pathways [24].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Characteristic Kinetic Signatures of Induced Fit vs. Conformational Selection

| Feature | Induced Fit Mechanism | Conformational Selection Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Order | Conformational change after binding [22] | Conformational change before binding [23] [22] |

| k˅obs vs. [L]₀ (Pseudo-First-Order) | Increases monotonically [22] | Increases if kₑ > k₋; Decreases if kₑ < k₋ [22] |

| k˅obs vs. [L]₀ (High [P]₀) | Symmetric curve with a minimum [22] | Asymmetric curve (if kₑ > k₋); Monotonically decreasing (if kₑ < k₋) [22] |

| Key Discriminating Experiment | Global analysis of kinetics with varied [L]₀ and known Kd [23] | Global analysis of kinetics with varied [L]₀ and known Kd [23] |

Table 2: Effects of Molecular Crowding on Protein-Ligand Interactions

| Observed Effect | Proposed Cause | Experimental Evidence from Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Altered Protein Stability | Balance between stabilizing excluded volume and destabilizing non-specific attractions [24] | Unfolded states trapped by interactions with crowders; Reduced folding cooperativity in multidomain proteins [24] |

| Modulated Enzyme Activity | Shifts in conformational equilibria between active/inactive states; competition for active site access [24] | Altered ligand binding pathways; accelerated or inhibited reaction rates in crowded simulations [24] |

| Retarded Diffusion & Cluster Formation | Volume exclusion and transient non-specific protein-protein contacts [24] | Formation of short-lived (< 1 μs) clusters in concentrated solutions, slowing rotational diffusion more than translational [24] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mechanistic Binding Studies

| Reagent | Function & Importance in Crowding Studies |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies (MAbs) | Highly specific capture or detection reagents in LBAs. Critical for quantifying "free" vs. "total" analyte. Lot-to-lot consistency must be managed [27]. |

| Engineered Proteins (Soluble Receptors) | Used as critical reagents to mimic the binding partner in assays. Essential for studying binding mechanisms without full cellular complexity [27]. |

| Inert Crowders (Ficoll, Dextran) | Polymers used to isolate the excluded volume effect from other interactions in crowding experiments [24] [25]. |

| Protein Crowders (BSA, Lysozyme) | Used to create a more physiologically relevant crowded environment, introducing both excluded volume and potential non-specific interactions [24]. |

| Biotinylated Ligands | Enable immobilization of one binding partner on streptavidin-coated surfaces for techniques like SPR, which is useful for analyzing binding kinetics under crowded conditions. |

Bridging the Gap: Experimental and Computational Methods for Crowding-Informed Assays

In protein-ligand binding research, the intracellular environment is not a dilute solution but a densely packed, crowded milieu. Macromolecular crowding, primarily an excluded volume effect, can significantly alter biochemical equilibria and reaction rates by reducing the available solvent volume. This technical guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs for researchers incorporating crowding agents like PEG and dextran into their binding assays, framed within the broader thesis of correcting for molecular crowding effects to achieve more physiologically relevant data.

Research Reagent Solutions: Crowding Agent Properties and Applications

Table 1: Key characteristics of common crowding agents and their low molecular weight analogues.

| Reagent Name | Primary Function | Key Considerations & Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [28] [29] [30] | Neutral, linear polymer crowder; induces depletion attraction. | Can engage in soft, non-specific interactions beyond excluded volume [29]. Effectiveness depends on molecular weight and concentration [30]. |

| Dextran [28] [30] | Branched polysaccharide crowder; used to mimic excluded volume. | Can have effects that differ from PEG even at the same mass/volume percent, indicating chemical interactions matter [30]. |

| Ficoll [30] | Synthetic, highly branched sucrose polymer crowder. | A synthetically defined alternative to dextran for studying excluded volume effects. |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) [28] | Low molecular weight analogue of PEG. | Serves as a viscogen control; helps distinguish between viscosity and specific crowding effects. |

| Glucose [28] | Low molecular weight analogue of dextran. | Serves as a viscogen control; helps distinguish between viscosity and specific crowding effects. |

| Lysozyme [30] | Protein-based crowding agent. | Represents a more natural, charged crowder; can reveal effects of weak, non-specific interactions. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Crowding Agent Experiments

FAQ 1: My binding assay shows no enhancement, or even a decrease, in affinity upon crowding. Is this expected? Yes, this is a possible and validated outcome. Contrary to the simple prediction that crowding always enhances binding, experimental data shows that for specific protein-protein interactions, the net effect can be minimal. A seminal study found that for high-affinity pairs like TEM1-BLIP and barnase-barstar, crowding agents like PEG and dextran caused only a minor reduction in association and dissociation rates, resulting in binding affinities quite similar to those in dilute solution [28].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Assay Conditions: Ensure you are using physiologically relevant concentrations of crowding agents (typically 2-20% w/v).

- Distinguish Viscosity from Crowding: Use low molecular weight analogues like ethylene glycol or glucose. These compounds increase solution viscosity without providing significant excluded volume. If your observed rate reduction matches that in these viscous controls, the effect is likely due to slowed diffusion rather than true crowding [28].

- Check for Non-Specific Interactions: Be aware that crowders are not always inert. PEG, for instance, can have soft, attractive interactions with your target molecules, which can either stabilize or destabilize them [29]. Try a different type of crowder (e.g., switch from PEG to dextran or Ficoll) to see if the effect is consistent.

FAQ 2: My ligand and protein are aggregating or precipitating in the presence of crowders. What is happening? This indicates that the crowding environment is promoting non-specific aggregation rather than the desired specific binding. This is particularly common for weakly interacting pairs or proteins with flexible, exposed surfaces.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Monitor for Aggregation: Use techniques like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to confirm and characterize aggregation [28].

- Optimize Crowder Concentration: Start with lower concentrations of the crowding agent and gradually increase while monitoring the reaction. High concentrations can strongly favor any associative process, including undesirable ones.

- Investigate Flexible Binding Sites: Research shows that crowding can destabilize main binding sites on protein surfaces, leading ligands to disperse to alternative, minor binding sites [21]. If your ligand binds to a flexible region, crowding may be altering the binding pathway.

FAQ 3: Why do different crowding agents (PEG vs. Dextran) produce different results in my assay? The excluded volume effect is a primary driver, but it is not the only factor. Crowders can engage in weak chemical interactions (electrostatic, hydrophobic) with your proteins, and these interactions are polymer-specific.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Acknowledge Polymer Chemistry: Do not assume all crowders are equivalent. For example, dextran and PEG have been shown to have opposite effects on the folding of ubiquitin [30].

- Systematic Comparison: Design experiments to compare multiple crowding agents (e.g., PEG, dextran, Ficoll) at the same mass/volume concentration. Consistent results across different chemistries strengthen the case for a pure excluded volume effect. Divergent results highlight the role of chemical interactions [30].

- Consider the In Vivo Reality: The cellular interior contains a heterogeneous mix of crowders. Using a single agent like PEG may not recapitulate the full complexity. Supplementing with biologically relevant crowders like cell extracts can provide deeper insight [29].

Core Experimental Concepts and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the key competing forces that determine the net effect of a crowding agent on a binding reaction.

Validating Crowding Effects: A Methodology for Binding Assays This protocol outlines a systematic approach using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and stopped-flow kinetics to dissect crowding effects, based on established methodologies [28].

Objective: To determine the effect of macromolecular crowding on the association rate ((k{on})), dissociation rate ((k{off})), and equilibrium binding affinity ((K_D)) of a protein-ligand pair.

Materials:

- Purified protein and ligand.

- Crowding agents: High molecular weight PEG (e.g., PEG8000) and dextran (e.g., Dextran70000).

- Low molecular weight controls: Ethylene Glycol (EG) and Glucose.

- SPR instrument (e.g., BioRad ProteOn) or stopped-flow fluorometer.

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) instrument.

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of assay buffers containing your crowding agents (PEG, dextran) and control viscogens (EG, glucose) across a range of concentrations (e.g., 0%, 5%, 10%, 15% w/v). Measure the viscosity of each solution.

- Equilibrium Binding via SPR:

- Immobilize the ligand on an SPR chip.

- Flow protein at different concentrations over the surface in each crowding condition.

- Analyze the sensorgrams to determine the equilibrium response. Plot response vs. concentration to obtain the (K_D) under each condition.

- Kinetic Analysis via SPR or Stopped-Flow:

- SPR: From the same sensorgrams, extract the association and dissociation rate constants ((k{on}), (k{off})) by fitting to a suitable binding model.

- Stopped-Flow: Rapidly mix protein and ligand in the crowder solution and monitor a signal change (e.g., fluorescence). Fit the resulting kinetic trace to determine (k_{on}).

- Viscosity Control Analysis: Compare the measured (k{on}) in crowded solutions to the values in low MW viscogen solutions of the same viscosity. If the reduction in (k{on}) is similar, it is likely a simple viscosity effect. If the reduction is smaller, a genuine crowding effect (depletion attraction) may be counteracting the viscosity [28].

- Aggregation Check (DLS): Perform DLS measurements on protein and ligand alone in the crowding conditions to rule out non-specific aggregation as a confounding factor [28].

Key Technical Takeaways

- No Universal Rule: Crowding does not always enhance binding affinity; it can have minimal, negative, or complex effects depending on the system [28].

- Agents Are Not Inert: Choose your crowder wisely. PEG and dextran can produce different results due to weak, chemistry-specific interactions beyond excluded volume [29] [30].

- Always Use Viscosity Controls: Low molecular weight analogues like ethylene glycol and glucose are essential for deconvoluting the effects of slowed diffusion from true crowding [28].

- Monitor for Aggregation: Crowding can promote non-specific aggregation, especially for flexible proteins or weak binders. Use DLS to confirm the system's integrity [28].

FAQs: Understanding and Implementing Crowded Assays

Q1: What is molecular crowding and why is it critical to account for in binding assays?

Molecular crowding refers to the highly concentrated environment inside cells, where macromolecules like proteins and nucleic acids can occupy up to 40% of the total volume, equivalent to concentrations of 80–400 mg/mL [31] [11]. This creates a crowded milieu with severely restricted amounts of free water and space. In this environment, the presence of countless other molecules excludes access to a significant volume, a phenomenon known as the excluded volume effect [11]. This effect increases the thermodynamic activity of solutes and can significantly influence biochemical processes by favoring compact states and association reactions. In binding assays, failing to account for this can lead to data that does not reflect true in vivo behavior, as crowding can stabilize protein-ligand complexes, enhance pathological aggregation, and alter binding affinities and kinetics [31] [11] [32].

Q2: My Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) data in complex biofluids like blood is unreliable due to high background noise and fouling. What solutions exist?

This is a common challenge, as biosensors are hampered by nonspecific adsorption of proteins and interference from cells in crude blood [33]. A proven solution is to integrate a microdialysis chamber with your SPR sensor.

- Principle: A microporous membrane is placed between the blood sample and the sensor surface, creating a diffusion gate. Small, fast-diffusing molecules (like many therapeutic drugs or peptides) migrate rapidly through the membrane to the sensor, while larger proteins and blood cells are significantly retarded [33].

- Implementation: As described by Breault-Turcot and Masson, a custom PDMS fluidic chamber is assembled with a spacer on the SPR prism. The chamber is filled with buffer, and the microporous membrane is placed on top before latching the fluidic cell. This setup allows for the affinity measurement of a small peptide directly in whole blood without any pre-treatment [33].

Q3: How does macromolecular crowding specifically affect the measured binding affinity in assays?

Crowding agents exert a modest but significant stabilization on binary protein-protein interactions. Direct quantitative measurements on the E. coli polymerase III subunits showed that crowding agents like dextran and Ficoll at 100 g/l lower the binding free energy by approximately 1 kcal/mol, which corresponds to about a fivefold increase in the binding constant [32]. This stabilization is largely attributed to excluded-volume interactions. When two proteins form a specific complex, their total effective volume is reduced, thereby minimizing the unfavorable excluded-volume interactions with the surrounding crowders [32]. It is crucial to note that while this effect on a single binding step may seem modest, it is cumulative in the formation of higher oligomers (like fibrils or replication complexes), leading to substantial stabilization and dramatic biological consequences [32].

Q4: When using Equilibrium Dialysis, what are the best practices to ensure accurate determination of the free fraction?

Equilibrium dialysis is considered a gold standard for measuring free drug concentrations or binding constants [34] [35]. Key practices include:

- Membrane Selection: Select a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) that is at least half the size of the species to be retained and/or twice the size of the species intended to pass through [36].

- Preventing Contamination: Use sterile buffers for membrane preparation and store hydrated membranes in a preservative like 0.1% sodium azide or 20% ethanol to prevent microbial degradation of the membrane [36].

- Achieving Equilibrium: Equilibration typically takes less than 6 hours at 37°C with shaking at 80-100 rpm. We recommend performing a kinetic experiment to determine the required time for your specific compound [36].

- Preventing Leakage: Ensure a proper seal and avoid creating micro-striations on the Teflon blocks by cleaning with non-abrasive detergents and no brushes [36].

- Data Correction: Correct for dilution factors during sample analysis. The fraction unbound (fu) is calculated as the concentration in the buffer chamber divided by the concentration in the sample (e.g., plasma) chamber [36] [34].

Q5: How can I achieve High-Throughput Screening (HTS) with Equilibrium Dialysis for early drug development?

Traditional equilibrium dialysis is not amenable to HTS, but 96-well format equilibrium dialysis plates have been successfully developed to meet this need [35]. These systems reduce assay sample volumes (e.g., 25-75 µL) to minimize reagent costs and are compatible with robotic workstations. Validation studies with drugs of varying binding properties (e.g., propranolol, paroxetine, losartan) have shown that the apparent free fraction obtained by this high-throughput method correlates well with values from traditional techniques [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubles Guide 1: Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) in Crowded Media

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background signal in serum/blood | Nonspecific adsorption of proteins and cells to sensor surface [33]. | Implement a microdialysis chamber with a microporous membrane to filter cells and slow large proteins [33]. |

| Use an ultralow fouling surface coating (e.g., polyethylene glycol (PEG) or zwitterionic molecules) [33]. | ||

| Unexpected binding kinetics/affinity | Macromolecular crowding altering the thermodynamic activity of your analyte [31] [32]. | Mimic the in vivo environment by adding inert crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll, dextran) to your running buffer and compare results with dilute conditions [11] [32]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | The target analyte is too small or the refractive index change is minimal. | Ensure the sensor is calibrated. For small molecules, a diffusion-gated setup can help by enriching their concentration at the sensor surface relative to larger interferents [33]. |

Diagram 1: A logical flowchart for troubleshooting common SPR issues in crowded assays.

Troubles Guide 2: Equilibrium Dialysis / Microdialysis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Long equilibration times | System not shaken; temperature not optimized. | Shake the dialysis block at 80-100 rpm and incubate at 37°C to accelerate equilibrium [36]. |

| Membrane leakage (protein in buffer chamber) | Loss of membrane integrity [36]. | Ensure correct membrane preparation and storage. Sterilize Teflon blocks by autoclaving to eliminate microbial contamination [36]. |

| Inadvertent use of a double membrane [36]. | Carefully separate membranes after hydration before assembly. | |

| Poor data reproducibility | Volume shifts due to osmotic pressure; non-specific adsorption. | Use precise pipetting and consider the potential for adsorption. For charged molecules, be aware of potential artifacts [34]. |

| Low throughput is a bottleneck | Using a standard, low-volume dialysis device. | Transition to a validated 96-well equilibrium dialysis plate format designed for high-throughput applications [35]. |

Diagram 2: A flowchart for resolving common problems in equilibrium dialysis and microdialysis.

Research Reagent Solutions for Crowded Assays

The following table lists commonly used crowding agents and other essential reagents for mimicking intracellular conditions and performing key experiments.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Macromolecular Crowding and Binding Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll 70 | Inert, highly branched polymer used to mimic crowded intracellular environment [11] [32]. | Hydrodynamic radius ~40 Å. Effective at concentrations of 37.5 mg/mL (≈17% fractional occupancy) [11]. |

| Dextran | Linear glucose polymer used as a crowding agent [32]. | Available in various molecular weights. Can have varying levels of non-specific interactions compared to Ficoll [32]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Flexible polymer chain used for crowding and to create ultralow fouling surfaces on sensors [33] [11]. | Efficiency depends on molecular weight. PEG 35000 has a hydrodynamic radius of ~57 Å [11]. Can sometimes induce aggregation beyond excluded volume effects. |

| Microporous Membrane | Size-based filtration in microdialysis-SPR and equilibrium dialysis; creates a diffusion gate [33] [36]. | Select MWCO carefully. For dialysis, MWCO should be at least half the size of the species to be retained [36]. |

| HTD96 Equilibrium Dialysis Plate | High-throughput 96-well format Teflon block for parallel determination of free fraction [36] [35]. | Compatible with robotic workstations. Reduces sample volumes to 25-75 µL, minimizing reagent costs [35]. |

Empirical data is essential for validating the impact of crowding in your experimental systems.

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Effects of Macromolecular Crowding on Biomolecular Interactions

| System / Interaction Studied | Crowding Agent & Concentration | Observed Effect | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Pol III ɛ- and θ-subunits binding [32] | Dextran or Ficoll 70 (100 g/L) | ~1 kcal/mol stabilization of binding free energy (≈5x increase in binding constant) | Modest stabilization of elemental binding steps is cumulative, leading to dramatic stabilization of large complexes [32]. |

| α-synuclein aggregation (linked to Parkinson's) [32] | PEG, Dextran, or Ficoll | Lag time shortened from months (in dilute buffer) to days | Increased cellular crowding with aging may promote susceptibility to aggregation-related diseases [32]. |

| Sickle hemoglobin polymerization [32] | Intrinsic crowding from high hemoglobin conc. in red cells (~300 g/L) | Significant impact on polymerization lag time and therapy effectiveness | Crowding must be accounted for in the design of therapies for diseases involving protein polymerization [32]. |

| Small peptide (DBG178) binding to CD36 [33] | N/A (measured directly in whole blood) | Successful affinity monitoring at µM concentrations in blood using microdialysis-SPR | Diffusion-gated sensing enables accurate measurement in biologically relevant, crowded environments without sample pre-treatment [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Challenges with Co-Folding Models

Q1: My co-folding model places the ligand in the original binding site even after I've mutated key binding residues. Is the model ignoring my changes?

A: This is a recognized limitation where co-folding models can overfit to statistical patterns in their training data rather than strictly adhering to physical principles. A 2025 study investigating the physics of protein-ligand interactions created adversarial examples by mutating all binding site residues to glycine (removing side-chain interactions) or phenylalanine (occupying the original pocket space). The models, including AlphaFold3 and RoseTTAFold All-Atom, often continued to place the ligand in the original site despite the biologically implausible context, sometimes even resulting in unphysical steric clashes [37].

- Recommended Action: Do not rely solely on co-folding predictions. Validate the predicted pose using physics-based docking tools like AutoDock Vina, which calculate binding affinity based on force fields. If the mutated residues should logically prevent binding, trust the physical reasoning over the deep learning output [37].

Q2: How can I account for molecular crowding in my protein-ligand binding predictions?