Avoiding PCR Hairpins: A Comprehensive Guide to Primer Design Best Practices for Reliable Results

This article provides a complete guide for researchers and drug development professionals on preventing hairpin structures in PCR primer design.

Avoiding PCR Hairpins: A Comprehensive Guide to Primer Design Best Practices for Reliable Results

Abstract

This article provides a complete guide for researchers and drug development professionals on preventing hairpin structures in PCR primer design. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, it details how intra-primer complementarity can lead to failed experiments through non-specific amplification or reduced yield. Readers will learn to identify hairpin risks, apply design rules and software tools to avoid them, troubleshoot problematic primers, and implement validation workflows to ensure assay specificity and efficiency, ultimately saving time and resources in molecular biology and clinical diagnostics.

Understanding Hairpin Structures: The What and Why of Primer Secondary Structures

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) experiments, the specificity and yield of amplification are fundamentally determined by the effective design of oligonucleotide primers. Among the various structural pitfalls in primer design, the formation of hairpin loops represents a critical failure point that can compromise experimental outcomes. Hairpin loops, or intra-primer complementarity, occur when a single primer folds back on itself, creating a stable secondary structure that prevents the primer from annealing to its target DNA template [1]. This self-complementarity is not merely a theoretical concern but a practical problem that manifests in failed amplifications, nonspecific products, and ultimately, wasted resources and time in molecular biology workflows.

The formation of these secondary structures is governed by basic thermodynamic principles. Regions within a primer sequence that are inverted complements can hybridize, forming a stem-loop structure consisting of a double-stranded stem and a single-stranded loop [2]. When such structures form, the primer becomes preoccupied with its own internal configuration rather than binding to the intended template. For researchers, drug development professionals, and scientists working with PCR-based diagnostics and assays, understanding and preventing hairpin formation is not optional—it is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data. This application note details the mechanisms of hairpin-mediated PCR disruption and provides validated protocols for identifying and eliminating problematic primers before they reach the laboratory bench.

Structural Mechanisms of PCR Disruption

Thermodynamic Principles and Hairpin Formation

Hairpin structures form through intramolecular hybridization when two regions within a single primer sequence are complementary and can base-pair with each other. The stability of these structures is quantified by their Gibbs free energy (ΔG), where more negative values indicate stronger, more stable structures [3]. A primer with a strong propensity to form a hairpin (typically with a ΔG more negative than -9.0 kcal/mol) is likely to be unavailable for template binding during the critical annealing phase of PCR [3].

The formation of a hairpin typically requires a complementary region of at least three to four bases to form a stable stem, with a loop region that can vary in size [2]. The physical consequence is twofold. First, the sequestered primer cannot participate in the annealing process, effectively reducing the concentration of functional primers in the reaction. Second, if the 3' end of the primer is involved in the hairpin structure, DNA polymerase is unable to initiate extension, as the enzyme requires a free 3' hydroxyl group to begin synthesis [1]. This combination of reduced annealing efficiency and blocked extension frequently results in PCR failure or significantly reduced amplicon yield.

Experimental Consequences in Research Settings

The practical manifestations of hairpin formation in PCR are varied but consistently problematic. In qualitative PCR, researchers may observe complete amplification failure or significantly reduced yield on gels. In quantitative applications (qPCR), hairpin formation can cause increased cycle threshold (Ct) values, reduced amplification efficiency, and inaccurate quantification [1]. These issues are particularly problematic in diagnostic and drug development contexts, where false negatives or inaccurate quantification can have significant downstream consequences.

Hairpin issues are exacerbated in specialized PCR applications. For GC-rich amplification targets, where secondary structures are inherently more stable, the risk of hairpin formation increases substantially [4]. Similarly, in techniques like reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) or digital PCR, where template may be limited, any reduction in primer efficiency directly compromises assay sensitivity. The confounding nature of these problems often leads researchers on time-consuming troubleshooting odyssees, when the root cause lies in the initial primer design.

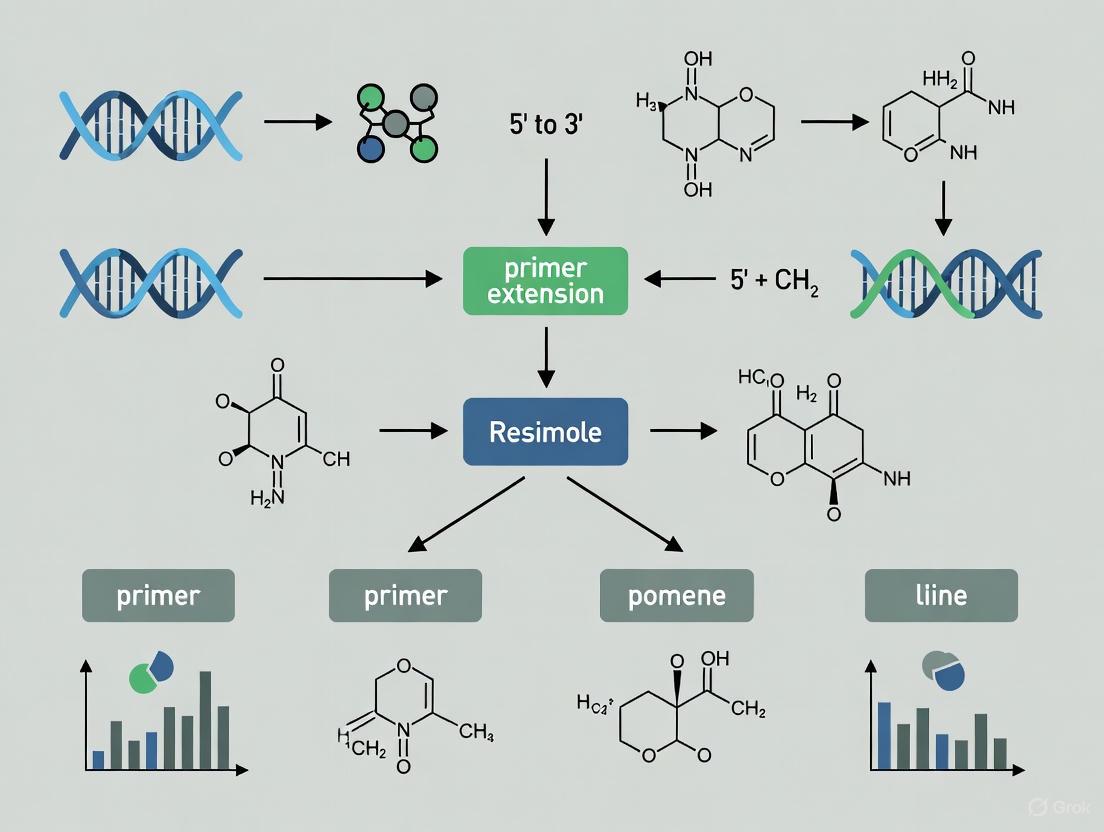

Diagram Title: Mechanism of Hairpin-Induced PCR Disruption

Quantitative Parameters for Hairpin Assessment

Thermodynamic Stability Thresholds

The propensity for hairpin formation can be quantified and predicted using thermodynamic parameters, allowing researchers to screen primers before synthesis. The most critical metric is the Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of the potential hairpin structure. Primers with hairpin ΔG values more negative than -9.0 kcal/mol should be rejected, as these structures are sufficiently stable to interfere with PCR [3]. For high-stringency applications, such as qPCR or multiplex assays, maintaining a less negative ΔG (closer to zero) provides an additional safety margin.

Melting temperature (Tm) also plays a role in hairpin stability. While the Tm of primer-template binding is typically optimized between 60-64°C [3], the Tm of any potential hairpin structure should be considered relative to the assay's annealing temperature. If the hairpin Tm approaches or exceeds the annealing temperature, the structure is likely to remain stable during the PCR cycling, effectively sequestering the primer. This is particularly problematic when the annealing temperature is low (below 55°C), as more permissive conditions allow weaker hairpins to persist.

Structural Parameters and Sequence Composition

The physical dimensions of potential hairpins provide additional screening criteria. The stem length is a critical factor, with stable structures requiring at least 3-4 complementary base pairs. The loop region typically consists of 4 or more nucleotides, with smaller loops generally forming more stable structures due to reduced entropy [2]. When screening primers, special attention should be paid to the 3' end, as complementarity in this region is particularly detrimental due to the polymerase's requirement for a free 3' hydroxyl group for extension.

Sequence composition significantly influences hairpin stability. GC-rich stems form more stable structures due to the three hydrogen bonds between G and C bases, compared to the two hydrogen bonds in A-T base pairs [1]. This means that a primer with a GC-rich self-complementary region poses a greater risk than one with AT-rich complementarity. Additionally, runs of identical nucleotides or palindromic sequences dramatically increase the risk of hairpin formation and should be avoided during design [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Hairpin Risk Assessment

| Parameter | Low Risk Range | Moderate Risk Range | High Risk Range | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG (kcal/mol) | > -3.0 | -3.0 to -9.0 | < -9.0 | Thermodynamic calculation [3] |

| Stem Length (bp) | 0-2 | 3-4 | ≥5 | Sequence complementarity analysis |

| Loop Size (nt) | >7 | 4-7 | <4 | Structural prediction |

| 3' End Involvement | No complementarity | Complementarity in middle | 3' end in stem | Sequence inspection |

| GC Content in Stem | <40% | 40-70% | >70% | Sequence composition analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Detection and Validation

In Silico Prediction and Analysis Workflow

Computational prediction represents the most efficient first line of defense against hairpin-related PCR failure. The following protocol provides a systematic approach for in silico hairpin screening:

Sequence Input and Parameter Setup: Begin by obtaining your primer sequences in FASTA format. Access a reliable oligonucleotide analysis tool such as the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool, Eurofins Genomics tools, or the Primer3 suite [1] [3] [5].

Secondary Structure Analysis: Submit each primer sequence for secondary structure prediction. Specify the reaction conditions that match your intended PCR protocol, including monovalent ion concentration (typically 50 mM), magnesium concentration (commonly 3 mM), and oligonucleotide concentration (usually 0.2-0.5 μM) [3]. These parameters affect hairpin stability and must be accurately represented.

Results Interpretation: Examine the output for predicted hairpin structures. Note the ΔG value, stem length, and whether the 3' end is involved. Compare these values against the thresholds established in Table 1. Any primer with a hairpin ΔG more negative than -9.0 kcal/mol should be eliminated from consideration [3].

Comparative Analysis: If possible, run the same analysis across multiple tools to confirm predictions. Small variations in algorithms and thermodynamic parameters can lead to different predictions. Consistent results across platforms increase confidence in the assessment.

Iterative Redesign: For primers failing the hairpin screen, implement minor sequence adjustments. Lengthening or shortening the primer by a few bases, or shifting the binding site slightly, can often eliminate self-complementarity while maintaining target specificity. Re-analyze modified sequences until all hairpin risks are mitigated.

Empirical Validation Using Melt Curve Analysis

While computational prediction is valuable, empirical validation provides definitive evidence of hairpin formation. The following protocol uses SYBR Green-based melt curve analysis to detect secondary structures:

Materials Required:

- Purified primer stocks (100 μM storage concentration, 10 μM working concentration)

- SYBR Green I nucleic acid stain (diluted according to manufacturer's recommendations)

- Real-time PCR instrument with melt curve capability (e.g., ABI PRISM 7700, Cepheid SmartCycler, or equivalent)

- Standard PCR buffer (typically containing 50 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl₂, 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.4)

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a reaction mixture containing 1× PCR buffer, appropriate dilution of SYBR Green I, and 0.2 μM of the test primer. Omit template DNA and the second primer to prevent interference. Include a no-template control with nuclease-free water.

Thermal Denaturation and Annealing: Program the thermal cycler with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by a slow cooling ramp to 25°C at 0.1°C per second to allow optimal secondary structure formation.

Melt Curve Analysis: After the annealing step, initiate a slow melt curve from 25°C to 95°C with continuous fluorescence monitoring. Use a temperature ramp rate of 0.1-0.2°C per second for high-resolution data.

Data Interpretation: Analyze the resulting melt curve for transitions occurring at temperatures below the expected primer-template melting temperature. A distinct melting transition in the absence of template indicates stable secondary structure. The temperature of this transition corresponds to the hairpin Tm, with higher values indicating more stable structures.

This protocol can be adapted for conventional PCR instruments by using non-fluorescent intercalating dyes and gel-based detection, though with reduced sensitivity and quantification capability compared to real-time instrumentation.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hairpin Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | Predicts ΔG of hairpin structures | In silico primer screening and design phase |

| Primer3 Software Suite | Incorporates hairpin prediction in primer design | Initial primer selection and optimization |

| SYBR Green I Nucleic Acid Stain | Fluorescent detection of secondary structures | Empirical validation via melt curve analysis |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Reduced extension of misfolded primers | PCR amplification with problematic templates |

| DMSO or Betaine Additives | Destabilization of secondary structures | Amplification of primers with moderate hairpin risk |

Integrated Prevention Strategies in Primer Design

Proactive Design Principles

Preventing hairpin formation begins with incorporating specific design principles during the initial primer conception phase. The most effective approach involves maintaining a balanced GC content between 40-60% while avoiding clusters of G or C bases, particularly at the 3' end [4] [1]. This composition reduces the likelihood of stable GC-rich stems forming within the primer. Additionally, designers should consciously avoid palindromic sequences and runs of identical nucleotides (e.g., "AAAA" or "GGGG"), as these significantly increase self-complementarity potential [2].

The placement of G and C residues throughout the primer sequence deserves special attention. While a balanced GC distribution is important, many guidelines recommend including one or two G or C bases within the last five nucleotides at the 3' end—a design feature known as a GC clamp [1]. This promotes specific binding at the extension point while avoiding the instability of an AT-rich 3' end. However, this must be balanced against the risk of creating a stable hairpin stem, particularly when more than three G/C residues are concentrated at the 3' end [1].

Computational Tools and Specificity Verification

Modern primer design leverages sophisticated software tools that automatically incorporate hairpin screening alongside other critical parameters. Primer-BLAST represents a particularly valuable resource as it combines the primer design capabilities of Primer3 with comprehensive specificity checking against genomic databases [6] [7]. This integrated approach ensures that selected primers are not only free of secondary structures but also specific to the intended target sequence.

The implementation of these tools follows a logical workflow: after defining the target region, researchers can set specific constraints for hairpin formation within the design parameters. Most tools allow users to adjust the stringency of secondary structure rejection, with recommended settings excluding primers with potential hairpins having ΔG values below -9.0 kcal/mol [3]. Following automated design, manual verification using tools like OligoAnalyzer provides an additional layer of security, allowing researchers to visually confirm the absence of problematic structures before proceeding to synthesis.

Diagram Title: Primer Design Workflow with Integrated Hairpin Screening

Hairpin loops represent a significant yet preventable obstacle in PCR-based research and diagnostic applications. Through understanding the structural mechanisms of hairpin formation, implementing rigorous quantitative assessment protocols, and adhering to proactive design principles, researchers can systematically eliminate this source of PCR failure. The integration of computational prediction tools early in the design process, followed by appropriate empirical validation, creates a robust framework for ensuring primer efficacy. For the scientific community engaged in drug development, diagnostic design, and basic research, mastery of these principles translates directly to improved experimental reproducibility, reduced resource waste, and accelerated research timelines. As PCR technologies continue to evolve toward higher sensitivity and multiplexing capabilities, vigilance against fundamental pitfalls like hairpin formation becomes increasingly critical to success.

Hairpin structures, also known as stem-loop structures, form when a single-stranded nucleic acid sequence contains two complementary regions that base-pair with each other, creating a double-stranded "stem" and an unpaired "loop" region. These secondary structures are particularly prevalent in GC-rich sequences, where the stronger triple hydrogen bonds between guanine and cytosine nucleotides create exceptionally stable structures that resist denaturation. In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other amplification methods, such hairpin formations represent a significant thermodynamic barrier to successful amplification, often leading to reaction failure or non-specific products that compromise experimental results and data integrity.

The formation of intramolecular hairpins is governed by fundamental thermodynamic principles, primarily the Gibbs free energy (ΔG), where more negative values indicate greater stability of the secondary structure. When the ΔG of hairpin formation is more favorable than the ΔG of primer-template binding, the equilibrium shifts toward hairpin formation, effectively sequestering primers from their intended targets. This molecular competition underlies most amplification failures attributed to secondary structures and necessitates careful primer design and reaction optimization, particularly for applications requiring high precision such as diagnostic assay development, mutational analysis in cancer research, and quantification of gene expression in therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Amplification Failure

Primer Sequestration and Reduced Effective Concentration

When primers form stable hairpin structures, they become thermodynamically unavailable for binding to the target DNA template. This auto-annealing effectively reduces the functional primer concentration in the reaction, despite the correct physical amount being present. The polymerase enzyme cannot initiate DNA synthesis from a self-folded primer, leading to failed amplification or dramatically reduced yield due to insufficient primer-template complexes. The stability of these hairpins is directly related to their ΔG values, with structures having ΔG < -3 kcal/mol being particularly problematic as they remain stable at standard annealing temperatures [8].

The molecular consequence of this sequestration is particularly pronounced at the critical 3' end of the primer. If the 3' terminus is involved in hairpin formation, the 3'-OH group required for polymerase-mediated extension becomes sterically blocked, preventing the addition of nucleotides even if partial binding occurs. This effect explains why otherwise well-designed primers sometimes fail completely in amplification reactions, as the polymerase is fundamentally unable to access the initiation site for DNA synthesis [2].

Polymerase Stalling and Incomplete Extension

GC-rich regions that form hairpins in the template DNA itself present a physical barrier to polymerase progression during the extension phase of PCR. DNA polymerases frequently stall at these stable secondary structures, resulting in truncated amplification products that are non-functional for downstream applications. The stronger triple hydrogen bonds in GC-rich regions require more energy to denature, and standard polymerase enzymes often lack the processivity to completely unwind these structures during replication [9].

This stalling phenomenon creates a mixture of full-length and shortened products that manifest as smearing on agarose gels rather than distinct bands. The consequences extend beyond failed amplification to include reduced sensitivity in detection methods and inaccurate quantification in quantitative PCR applications. Furthermore, these truncated products can themselves act as primers in subsequent cycles through a process called primer-dimer formation, amplifying non-specific background and further reducing the reaction efficiency [9] [2].

Non-Specific Amplification and Off-Target Binding

When intended priming sites are occluded by hairpin structures, primers may bind to alternative, partially complementary sites on the template DNA with lower thermodynamic stability. This off-target binding becomes favorable when the optimal binding site is inaccessible, leading to amplification of unintended sequences that consume reaction components without producing the desired product. The result is often multiple bands on an electrophoresis gel or complete absence of the target band amid non-specific amplification [2] [10].

The temperature dependence of this phenomenon is particularly significant. If the annealing temperature is set too low to compensate for suspected hairpin structures, it further promotes non-specific binding by reducing the stringency required for primer-template hybridization. This creates a challenging optimization balance where increasing temperature might overcome hairpin stability but reduce specific binding, while decreasing temperature improves general binding but exacerbates off-target effects [10].

Detection and Analysis Methods

In Silico Prediction Tools and Parameters

Modern oligonucleotide design relies on sophisticated bioinformatic tools that predict secondary structure formation using thermodynamic parameters. These tools calculate the minimum free energy (MFE) of potential hairpin structures, allowing researchers to identify problematic primers before synthesis. The most accurate algorithms utilize nearest-neighbor thermodynamics based on SantaLucia's unified parameters (1998), which account for sequence context and provide ±1-2°C accuracy in melting temperature prediction compared to ±5-10°C for simple GC% methods [8].

Table 1: Critical Parameters for Hairpin Prediction

| Parameter | Threshold Value | Consequence of Deviation | Tool/Method for Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin ΔG | > -3 kcal/mol | Stable structures that interfere with binding | OligoAnalyzer, mFold |

| 3' End Complementarity | < 3 contiguous bases | Polymerase extension blockage | Self-Complementarity Analysis |

| GC Content | 40-60% | Increased hairpin stability | GC Content Calculator |

| Run of Identical Bases | < 4 | Promotes mispriming and slippage | Sequence Scanner |

When evaluating potential hairpins, particular attention must be paid to the 3' terminus stability, as this region is critical for polymerization initiation. Most prediction tools provide detailed thermodynamic calculations for local structures, enabling targeted redesign of problematic sequences. Additionally, the temperature of hairpin dissociation should be compared to the planned annealing temperature, as structures that remain stable above the annealing temperature will persistently interfere with amplification [2] [10].

Experimental Validation Techniques

While in silico prediction provides valuable guidance, experimental validation remains essential for confirming hairpin interference in amplification reactions. Gradient PCR serves as a first-line diagnostic approach, testing a range of annealing temperatures to determine if amplification failure persists across conditions. A consistent lack of specific product despite temperature optimization strongly suggests structural rather than parametric issues [10].

For more detailed analysis, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) can resolve individual hairpin species and their relative abundances when primers are incubated under reaction conditions without template. This method provides direct visual evidence of secondary structure formation and can help quantify the proportion of primers involved in stable structures. Additionally, melting curve analysis with intercalating dyes can detect structural transitions in primer solutions, confirming the stability predictions obtained from computational tools and informing redesign strategies [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Hairpin Challenges

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Overcoming Hairpin-Related Amplification Issues

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Mechanism of Action | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerases | OneTaq DNA Polymerase, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enhanced processivity to unwind secondary structures | GC-rich templates (>60% GC) |

| GC Enhancers | OneTaq GC Enhancer, Q5 High GC Enhancer | Additive mixtures that reduce secondary structure formation | Templates with pronounced hairpin tendency |

| Denaturing Additives | DMSO (5-10%), Betaine (1-1.5 M), Formamide | Lower melting temperature of secondary structures | Standard polymerases with problematic templates |

| Modified Nucleotides | 7-deaza-2'-deoxyguanosine | Reduces hydrogen bonding without affecting base pairing | Extremely GC-rich regions |

| Salt Optimization | MgCl₂ (1.0-4.0 mM gradient) | Stabilizes DNA duplex while affecting polymerase activity | Fine-tuning specific reactions |

The strategic application of these reagents must be tailored to the specific hairpin challenge. For instance, DMSO works by reducing secondary structure formation through destabilization of base pairing, effectively lowering the melting temperature of hairpins by approximately 0.5-0.7°C per 1% concentration. Similarly, betaine (also known as trimethylglycine) equalizes the thermal stability of AT and GC base pairs, preventing the formation of stable GC-rich hairpins without adversely affecting polymerase activity at recommended concentrations [9].

For particularly challenging templates, specialized polymerases with enhanced strand-displacement activity provide the most reliable solution. These enzymes contain modifications that allow them to unwind secondary structures during extension, effectively bypassing the hairpin barriers that stall conventional polymerases. When using these systems, it is often beneficial to employ extended elongation times and higher extension temperatures to further facilitate complete amplification through structured regions [9].

Experimental Protocols for Hairpin Resolution

Protocol 1: PCR Optimization for GC-Rich Templates

This protocol provides a systematic approach to amplify templates with significant secondary structure formation, particularly those with GC content exceeding 60%. The procedure combines specialized reagents and cycling parameters to overcome hairpin-related amplification failure.

Materials Required:

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase with GC enhancer (e.g., Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase with Q5 High GC Enhancer)

- Template DNA (10-100 ng genomic DNA or 1-10 ng plasmid DNA)

- Forward and reverse primers (10 μM working concentration)

- Additional DMSO (molecular biology grade)

- Thermocycler with gradient capability

Procedure:

- Prepare the master mix according to the following composition:

- 10 μL 5X GC Buffer

- 10 μL Q5 High GC Enhancer

- 1 μL 10 mM dNTPs

- 1.5 μL Forward Primer (10 μM)

- 1.5 μL Reverse Primer (10 μM)

- 0.5 μL Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase

- 1 μL Template DNA

- 2.5 μL DMSO

- Nuclease-free water to 50 μL final volume

Set up a thermocycling protocol with the following parameters:

- Initial Denaturation: 98°C for 30 seconds

- 35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 98°C for 10 seconds

- Annealing: Gradient from 55°C to 72°C for 20 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 30 seconds per kb

- Final Extension: 72°C for 2 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

Analyze 5 μL of the reaction products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

For successful reactions, optimize further by adjusting the Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.5 mM increments between 1.0 and 4.0 mM to determine the ideal conditions [9].

Protocol 2: Hairpin Disruption by Thermal Denaturation

This protocol employs strategic thermal conditioning to disrupt stable secondary structures before amplification begins, particularly effective for templates with pronounced hairpin formation tendencies.

Materials Required:

- Standard or high-fidelity DNA polymerase

- Template DNA

- Primers (validated for specificity)

- Standard PCR reagents

Procedure:

- Prepare the PCR reaction mixture according to standard protocols for your selected polymerase, excluding the enzyme.

Subject the complete reaction mixture (without polymerase) to a pre-PCR heat treatment:

- 95°C for 3-5 minutes

- Immediately transfer to 80°C and hold

During the 80°C hold step, add the DNA polymerase (hot start format recommended) to the reaction mixture.

Immediately commence standard thermocycling with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 30 seconds.

For templates with extreme secondary structure, incorporate a prolonged denaturation step (98°C for 2-3 minutes) in the first cycle only, followed by standard denaturation times (5-10 seconds) in subsequent cycles [12].

Protocol 3: Primer Redesign and Validation Workflow

When reagent-based and condition-based optimizations fail, systematic primer redesign provides the most reliable solution to hairpin-related amplification failure.

Procedure:

- Identify problematic sequences using in silico tools:

- Input candidate primer sequences into prediction software (e.g., OligoAnalyzer)

- Flag primers with hairpin ΔG < -3 kcal/mol

- Specifically identify 3' terminal complementarity (>3 bases)

Implement redesign strategies:

- Shift binding position 20-50 bases upstream or downstream

- Adjust length to 18-24 nucleotides while maintaining Tm

- Modify GC content toward 40-60% range

- Eliminate runs of identical bases (>4) or dinucleotide repeats

Validate redesigned primers:

- Calculate new Tm values ensuring pair matching within 2°C

- Verify specificity using BLAST against appropriate genome databases

- Check for cross-homology with related sequences

- Confirm absence of stable secondary structures (ΔG > -3 kcal/mol)

Experimental validation:

Visualizing Hairpin Formation and Consequences

The diagram below illustrates the molecular pathways through which hairpin structures lead to amplification failure and non-specific products, highlighting critical intervention points for experimental resolution.

Figure 1: Molecular pathways of hairpin-induced amplification failure and intervention strategies.

Hairpin structures represent a fundamental challenge in molecular biology applications, particularly as research increasingly focuses on GC-rich genomic regions such as promoter sequences of therapeutic targets. The molecular consequences of these secondary structures—including primer sequestration, polymerase stalling, and subsequent non-specific amplification—can severely compromise experimental outcomes in drug development and diagnostic applications. However, through systematic implementation of the detection methods, specialized reagents, and optimized protocols outlined in this article, researchers can successfully overcome these challenges.

The integration of computational prediction tools early in experimental design, coupled with strategic application of GC-enhancement strategies and specialized enzyme systems, provides a robust framework for addressing hairpin-related amplification failures. As molecular techniques continue to evolve toward more multiplexed and precise applications, the principles of thoughtful primer design and reaction optimization covered in these application notes will remain essential components of successful experimental outcomes in scientific research and therapeutic development.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, with its success critically dependent on the effective design of oligonucleotide primers. Poorly designed primers can lead to issues such as non-specific amplification, primer-dimer formation, and failed reactions, ultimately compromising experimental results. This application note examines three fundamental factors in primer design—primer length, GC content, and sequence composition—within the context of a broader research thesis on avoiding hairpin structures. We provide quantitative guidelines, detailed protocols, and practical strategies to enable researchers to design primers that maximize amplification efficiency and specificity, particularly for challenging applications in drug development and diagnostic assay design.

Core Principles of Primer Design

Quantitative Design Parameters

The table below summarizes the universally recommended quantitative parameters for optimal primer design, synthesized from current molecular biology practices.

Table 1: Optimal Values for Key Primer Design Parameters

| Design Parameter | Recommended Value | Rationale and Additional Context |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides [13] [1] [14] | Shorter primers (~18-24 bp) bind more efficiently, while longer primers (up to 30 bp) offer higher specificity for complex templates [1]. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [13] [1] [15] | Balances primer stability and specificity. Content outside this range can lead to weak binding (>60%) or non-specific binding (<40%) [1]. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 65–75°C; within 5°C for a primer pair [13] [15] | Critical for setting the annealing temperature. Can be calculated as Tm = 4(G + C) + 2(A + T) [1]. |

| GC Clamp | G or C at the 3'-end; 2 G/C bases in the last 5 bases [13] [16] | The stronger hydrogen bonding of G/C bases stabilizes the primer-template complex at the critical point of polymerase binding [1] [16]. |

Sequence Composition and Hairpin Avoidance

Sequence composition directly influences the formation of detrimental secondary structures. Intra-primer homology (complementarity within the same primer) can lead to hairpin loops, while inter-primer homology (complementarity between forward and reverse primers) can lead to primer-dimer formation [13] [14]. These structures compete with the desired primer-template binding, reducing PCR efficiency and yield.

To minimize secondary structures:

- Avoid Repeats: Runs of four or more identical bases (e.g., AAAA) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATAT) can cause mispriming and should be avoided [13] [16].

- Check Complementarity: Use analyzer tools to ensure low "self-complementarity" and "self 3′-complementarity" scores [1].

- Ensure 3'- End Stability: The Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) of the five bases at the 3' end should not be overly negative (e.g., > -3 kcal/mol for internal hairpins), as this indicates a stable, difficult-to-disrupt secondary structure [16].

Advanced Considerations and Problem-Solving

Amplification of GC-Rich Templates

GC-rich sequences (≥60% GC content) present unique challenges due to their high thermodynamic stability, which promotes secondary structure formation and increases melting temperatures [17]. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach to amplify these difficult targets.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GC-Rich PCR

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Specialized Polymerase (e.g., OneTaq or Q5 High-Fidelity) | Polymerases optimized for GC-rich templates are less likely to stall at stable secondary structures [17]. |

| GC Enhancer / Buffer | Proprietary mixes containing additives (e.g., betaine, DMSO, glycerol) that help denature secondary structures and increase primer stringency [17]. |

| MgCl2 Solution | A cofactor for polymerase activity. Its concentration can be optimized (typically 1.0-4.0 mM) to improve yield and specificity in GC-rich PCR [17]. |

| Thermocycler with Gradient Function | Essential for empirically determining the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) by testing a range of temperatures simultaneously [14] [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Amplification of GC-Rich Sequences

1. Initial Setup - Primer Design: Design primers according to standard guidelines. If the target region has extreme GC content, consider codon optimization at the wobble position for cloning applications to reduce local GC content without altering the amino acid sequence [18]. - Reaction Assembly: Use a master mix formulated for GC-rich targets or a standalone polymerase. For a 25 µL reaction, combine: - Template DNA (75 ng genomic DNA or equivalent) - 1X Polymerase Buffer (often supplied with MgCl2) - 0.2 mM dNTPs each - 0.4 µM each forward and reverse primer - 1 U/µL DNA polymerase - 5% DMSO (v/v) or the supplier's recommended volume of GC Enhancer [18] [17].

2. Thermocycling Conditions - Initial Denaturation: 94°C for 4 minutes [18]. - Amplification (30-35 cycles): - Denaturation: 94°C for 30-50 seconds. - Annealing: Use a gradient starting from 5°C above the calculated Ta down to the calculated Ta (e.g., 63.3°C to 68°C) for 40-50 seconds [18] [17]. - Extension: 72°C for 1-2 minutes per kb. - Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes [18]. - Hold: 4°C.

3. Post-Amplification Analysis - Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis. - If non-specific products are observed, increase the annealing temperature in subsequent runs. - If no product is observed, lower the annealing temperature, increase the concentration of GC Enhancer, or optimize MgCl2 concentration in 0.5 mM increments [17].

In Silico Design and Specificity Validation

Computational tools are indispensable for modern primer design. Always validate primer specificity by performing an in silico PCR against a relevant genome database.

- Primer-BLAST: The NCBI Primer-BLAST tool is the gold standard for designing target-specific primers and checking for off-target amplification [6]. It combines Primer3's design capabilities with BLAST search to ensure primers are unique to the intended template.

- Local Analysis Tools: Software and online platforms (e.g., OligoPerfect Designer, Eurofins Genomics tools, Benchling) can calculate Tm, check for secondary structures, and analyze potential primer-dimer formation [1] [15] [16]. These tools help enforce the parameters listed in Table 1 during the design phase.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process of primer design, from initial parameterization to experimental validation.

The reliable performance of PCR hinges on meticulous primer design. Adherence to the quantitative guidelines for primer length, GC content, and Tm, coupled with diligent avoidance of problematic sequence compositions that lead to hairpins and primer-dimers, forms the foundation of success. For particularly challenging templates, such as GC-rich regions, a methodical approach involving specialized reagents and empirical optimization of reaction conditions is required. By integrating robust in silico design tools with systematic experimental validation, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure high-quality, reproducible results in their molecular assays.

Distinguishing Hairpins from Primer-Dimers and Other Secondary Structures

In molecular biology, the success of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) critically depends on the specific and efficient binding of primers to their target DNA sequences. Secondary structures such as hairpins and primer-dimers represent a frequent cause of experimental failure, leading to reduced amplification efficiency, nonspecific products, and inaccurate quantification. For researchers and drug development professionals, the ability to distinguish between these different structural anomalies is a fundamental diagnostic skill. This guide provides a detailed framework for identifying, understanding, and troubleshooting hairpins and primer-dimers within the broader context of robust primer design, ensuring the reliability of genetic analysis, diagnostic assay development, and therapeutic discovery.

Defining the Structures: Hairpins vs. Primer-Dimers

Understanding the fundamental differences in the origin and structure of hairpins and primer-dimers is the first step toward effective troubleshooting. The table below summarizes their key characteristics.

Table 1: Characteristics of Hairpins and Primer-Dimers

| Feature | Hairpin (or Self-Dimer) | Primer-Dimer |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | An intramolecular structure where a single primer folds back on itself [1]. | An intermolecular structure formed between two primers [1]. |

| Participants | One primer molecule [2]. | Two primer molecules (can be two of the same, "Self-Dimer," or Forward and Reverse, "Cross-Dimer") [1] [2]. |

| Primary Cause | Self-complementarity within the primer sequence, where two regions (e.g., of three or more nucleotides) are complementary [1]. | Complementarity between primers, especially at their 3' ends [19] [20]. |

| Impact on PCR | Prevents the primer from binding to the DNA template, leading to no or reduced amplification [21] [1]. | Consumes primers and generates short, unintended amplification products, competing with the target amplicon [1] [19]. |

Figure 1: Schematic of Secondary Structure Formation. This diagram illustrates the pathways through which a single primer or primer pair can form undesirable secondary structures, differentiating between intramolecular (hairpin) and intermolecular (primer-dimer) events.

Detection and Diagnostic Methodologies

A multi-faceted approach combining in silico prediction with experimental observation is required to definitively diagnose secondary structure issues.

In Silico Prediction and Analysis

Before ordering primers, always analyze their sequences computationally. Several free, powerful tools are available for this purpose [15] [3].

Key Tools and Their Functions:

- IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool: Critically used for calculating melting temperature (Tm) under specific reaction conditions, and for analyzing hairpins, self-dimers, and cross-dimers, providing a ΔG value for stability [19] [3].

- NCBI Primer-BLAST: Integrates primer design with specificity checking against genomic databases to ensure primers are unique to the intended target [2] [3].

- UNAFold Tool: (Also from IDT) Used for more detailed analysis of oligonucleotide secondary structure [3].

Interpretation of Thermodynamic Parameters (ΔG): The ΔG (Gibbs Free Energy) value indicates the stability of a secondary structure. A more negative ΔG value signifies a more stable, and therefore more problematic, structure [3].

- Acceptable ΔG: Values weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol are generally acceptable, though weaker is always better [3].

- Hairpin Tm: Also check the predicted Tm of any hairpin structure. If this Tm is close to or higher than your PCR annealing temperature, the hairpin will be stable and likely disrupt the reaction [19].

Table 2: In Silico Diagnostic Workflow for Secondary Structures

| Step | Action | Key Parameters to Check | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Input | Enter primer sequence(s) into analysis tool (e.g., OligoAnalyzer). | N/A | N/A |

| 2. Hairpin Analysis | Run secondary structure analysis. | ΔG of hairpin, Tm of hairpin. | ΔG > -9 kcal/mol; Hairpin Tm << PCR Annealing Temp [19] [3]. |

| 3. Dimer Analysis | Run self-dimer and cross-dimer analysis. | ΔG of dimer formation. | ΔG > -9 kcal/mol for all dimer types [3]. |

| 4. Specificity Check | Run BLAST analysis on each primer. | Number of off-target matches in the genome. | Unique binding to the intended target region [2] [3]. |

Experimental Detection and Validation

When experimental results are suboptimal, gel electrophoresis and melt curve analysis are key diagnostic techniques.

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Primer-Dimer Manifestation: Appears as a low molecular weight band, typically smeared or discrete, below the expected amplicon size. A common size range is 20-50 bp [19].

- Hairpin Manifestation: Results in a complete lack of product or a significant reduction in product yield, as the primers are unavailable for binding [1].

qPCR Melt Curve Analysis:

- In qPCR, following amplification, a melt curve analysis can be performed. A single, sharp peak at the temperature corresponding to your amplicon's Tm indicates a specific product. The presence of primer-dimers is often revealed by an additional peak at a lower temperature [22].

Figure 2: Experimental Diagnostic Workflow. A decision tree to guide the interpretation of common experimental outcomes in PCR and qPCR to diagnose hairpins and primer-dimers.

Proactive Primer Design to Avoid Secondary Structures

The most efficient strategy is to prevent these structures through careful primer design.

Foundational Design Parameters

Adhering to established design rules minimizes the risk of secondary structures.

Table 3: Optimal Primer Design Parameters to Avoid Secondary Structures

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale & Practical Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–30 nucleotides [21] [15] [23] (18–24 is common [1] [20]). | Shorter primers anneal faster but may lack specificity; longer primers increase specificity but risk secondary structures. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [8] [21] [1]. | GC bonds are stronger than AT bonds. A balanced GC content provides stability without promoting overly stable mis-priming. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 55–65°C [23] [2]; 60–64°C [3]. | Provides a sufficient thermal window for optimization. Both primers in a pair should have Tm values within 2°C of each other [3]. |

| 3' End (GC Clamp) | 1–2 G or C bases in the last 5 nucleotides [15] [23]. | Stabilizes binding at the critical point of polymerase extension. Avoid >3 G/Cs at the 3' end, as this promotes non-specific binding [1] [20]. |

| Self-Complementarity | Keep to a minimum. | Avoid repeats of a single base (e.g., AAAA) or di-nucleotides (e.g., ATATAT), and palindromic sequences [15] [2] [20]. |

Advanced Design Considerations

- Salt Concentration Adjustments: Tm calculations must account for buffer composition. The presence of monovalent (Na⁺, K⁺) and divalent (Mg²⁺) cations significantly stabilizes DNA duplexes. For example, increasing Mg²⁺ from 1.5 mM to 3.0 mM can raise Tm by +1.5 to +2.5°C [8]. Always input your exact buffer conditions into Tm calculators for accurate predictions [8] [3].

- Thermodynamic Calculation Methods: Use tools that employ nearest-neighbor thermodynamics (SantaLucia, 1998) rather than the simpler Wallace rule (4°C for G/C + 2°C for A/T). The nearest-neighbor method accounts for sequence context and salt effects, achieving ±1–2°C accuracy versus ±5–10°C for the GC% method [8].

- Additives for Problematic Templates: For GC-rich templates that are prone to secondary structures, additives like DMSO can be included. DMSO lowers the overall Tm by approximately 0.5–0.7°C per 1% concentration and helps disrupt secondary structures in both the primer and the template [8].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Secondary Structure Management

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool | Free online tool for analyzing Tm, hairpins, and dimers using nearest-neighbor thermodynamics and user-defined buffer conditions [3]. | First-line check for any new primer design before synthesis. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | Tool that combines primer design with specificity checking via BLAST to ensure primers are unique to the intended target [2]. | Verifying primer specificity for genomic DNA PCR. |

| DMSO (Dimethyl Sulfoxide) | A common PCR additive that reduces secondary structure formation by interfering with hydrogen bonding [8]. | Rescuing amplification of a GC-rich target where primers or template form stable structures. |

| HPLC Purified Primers | High-purity oligo synthesis method that removes truncated sequences and manufacturing byproducts [21] [15]. | Essential for applications like cloning, NGS, or qPCR where high efficiency and accuracy are critical. |

| Touchdown PCR Protocol | A PCR technique where the annealing temperature starts high (above estimated Tm) and is gradually reduced. This enriches specific products by favoring binding at the highest possible temperature [21]. | Improving specificity when minor primer-dimer or off-target binding is suspected. |

Distinguishing between hairpins and primer-dimers is a critical skill that hinges on understanding their distinct structural bases and manifestations. Hairpins are intramolecular folds that sequester the primer, while primer-dimers are intermolecular hybrids that consume reagents. A rigorous practice of in silico prediction using modern thermodynamic tools, coupled with adherence to proven primer design parameters, provides a powerful proactive strategy. When problems arise, a systematic diagnostic approach using gel electrophoresis and melt curve analysis allows for accurate identification and effective troubleshooting. By integrating these principles and protocols, researchers can significantly enhance the robustness and reproducibility of their PCR-based assays, thereby accelerating discovery and development in the life sciences.

Proactive Primer Design: Strategies and Tools to Prevent Hairpin Formation

In molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique, and its success critically depends on the design of oligonucleotide primers. Poorly designed primers can lead to experimental failure through non-specific amplification, primer-dimer formation, or the generation of secondary structures that inhibit replication. This application note details the core design rules—focusing on primer length, melting temperature (Tm), and GC content—that researchers must follow to minimize these risks. Adherence to these guidelines ensures robust, specific, and efficient amplification, which is paramount in sensitive downstream applications including gene expression analysis, cloning, and diagnostic assay development.

Core Parameter Optimization

The three most critical parameters for functional primer design are length, melting temperature, and GC content. Optimizing these factors in concert is essential for ensuring that primers bind specifically and efficiently to the target sequence.

Primer Length

Primer length directly governs its specificity and hybridization efficiency. Excessively long primers hybridize slowly and can reduce amplicon yield, whereas overly short primers may lack specificity, leading to off-target binding [1].

- Optimal Range: A length of 18 to 30 nucleotides is widely recommended for standard PCR [13] [3] [20]. For maximum specificity and annealing efficiency, a narrower range of 18–24 bases is often ideal [1].

- Rationale: Longer primers (>30 bases) exhibit slower hybridization rates and decreased annealing efficiency. Shorter primers (<18 bases) may fail to provide sufficient sequence complexity for unique binding, increasing the potential for amplification of non-target sequences [1].

Melting Temperature (T~m~)

The melting temperature is the temperature at which 50% of the primer-DNA duplex dissociates into single strands. It is a critical factor for determining the PCR annealing temperature.

- Optimal T~m~ Range: Aim for a T~m~ between 60°C and 75°C [13]. For optimal enzyme function and specificity, a T~m~ of 60–64°C is a common target, with 62°C being ideal [3].

- Primer Pair Compatibility: The T~m~ values for the forward and reverse primers should be within 5°C of each other, with a more stringent goal of within 2°C to ensure both primers bind to the target simultaneously and with similar efficiency [13] [3] [20].

- T~m~ Calculation: The T~m~ can be estimated using the nearest-neighbor method, which is incorporated into modern oligonucleotide analysis software. A rough calculation for shorter primers can be done with the formula: T~m~ = 4°C × (G + C) + 2°C × (A + T) [1] [20].

GC Content

GC content refers to the percentage of guanine (G) and cytosine (C) bases in the primer sequence. GC bases form three hydrogen bonds, compared to the two formed by AT bases, thus significantly influencing primer stability and T~m~ [1].

- Optimal Range: Maintain a GC content between 40% and 60%, with a target of 50% being ideal for most applications [13] [3] [1].

- GC Clamp: The 3' end of the primer should be stabilized by a GC clamp—the presence of one or two G or C bases in the last five nucleotides. This promotes specific binding at the site where the polymerase initiates extension. However, avoid stretches of more than three consecutive G or C bases at the 3' end, as this can promote non-specific binding [13] [1] [20].

Table 1: Summary of Core PCR Primer Design Rules

| Design Parameter | Optimal Range | Key Rationale | Risk of Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 nucleotides (18–24 ideal) [13] [3] [1] | Balances specificity with efficient hybridization and amplicon yield. | Short: Non-specific binding; Long: Reduced efficiency, secondary annealing. |

| Melting Temperature (T~m~) | 60–75°C [13] | Determines the optimal annealing temperature (T~a~). | Low T~m~: Non-specific amplification; High T~m~: Secondary annealing, no amplification. |

| Primer Pair T~m~ | Within 5°C (2°C ideal) [13] [3] | Ensures synchronous binding of both primers to the target. | Mismatched T~m~: One primer mispriming or failing to bind, reducing yield. |

| GC Content | 40–60% (50% ideal) [13] [3] [1] | Provides sufficient duplex stability without promoting mispriming. | Low: Weak binding; High: Mismatches, primer-dimer formation. |

| GC Clamp (3' end) | 1-2 G/C bases in last 5 nucleotides [13] [1] | Stabilizes the polymerase binding site for efficient extension. | >3 consecutive G/C: Non-specific binding and false positives. |

Risk Mitigation: Avoiding Secondary Structures

A primary risk in primer design is the formation of secondary structures, such as hairpins and primer-dimers, which compete with target binding and drastically reduce PCR efficiency. The core design parameters are the first line of defense against these structures.

Hairpins

Hairpins (or self-dimers) form when two regions within a single primer are complementary, causing the primer to fold onto itself [1].

- Cause: Regions of three or more complementary nucleotides within a primer [13].

- Mitigation:

- Design Tools: Use software to screen for self-complementarity. The Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of any predicted hairpin should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [3].

- Parameter Adjustment: Avoid runs of identical bases (e.g., ACCCC) or dinucleotide repeats (e.g., ATATATAT), as these increase the potential for intra-primer homology [13] [20].

Primer-Dimers

Primer-dimers occur when forward and reverse primers anneal to each other via complementary sequences, rather than to the template DNA. This results in the amplification of the primers themselves [1].

- Types:

- Self-dimer: Hybridization between two identical primers.

- Cross-dimer: Hybridization between the forward and reverse primer.

- Mitigation:

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing primers that minimize the risk of secondary structure formation.

Diagram: A logical workflow for designing primers with minimized risk of secondary structures. The process involves iterative checks of core parameters and structural compatibility.

Experimental Protocol: Primer Design and Validation

This section provides a detailed methodology for designing, validating, and implementing primers in a PCR assay, based on established best practices [24].

In Silico Design and Validation

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the target DNA sequence from a reliable database (e.g., NCBI, KEGG). For highly variable targets, use a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) of related sequences to identify conserved regions for pan-specific primer design [25] [24].

- Primer Design:

- Use dedicated software (e.g., Primer3, Geneious, IDT PrimerQuest) to generate candidate primer pairs.

- Input the core parameters from Table 1: length (18-30 nt), T~m~ (60-64°C), and GC content (40-60%).

- Specify the target amplicon size. For standard PCR, 70–150 bp is ideal for qPCR, while amplicons up to 500 bp can be used with adjusted cycling conditions [3].

- Specificity Check: Perform an in silico specificity validation using a tool like NCBI BLAST. This ensures the primers are unique to the intended target sequence and will not produce off-target amplicons [3] [20].

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Use oligonucleotide analysis tools (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer) to screen for hairpins and self-/cross-dimers. Reject any primers with a ΔG value stronger than -9.0 kcal/mol for these structures [3].

Laboratory Validation and Optimization

- Primer Reconstruction: Resusynthesized lyophilized primers in a suitable buffer (e.g., TE) to a stock concentration of 100 µM. Store at -20°C.

- PCR Setup:

- Reaction Mix: Assemble a standard 25 µL reaction containing:

- 1X PCR buffer (with Mg²⁺)

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- 0.2–0.5 µM of each primer

- 0.5–1.0 U of DNA polymerase

- Template DNA (e.g., 10–100 ng genomic DNA)

- Positive Control: Use a template known to contain the target sequence.

- Negative Control: Use nuclease-free water instead of template.

- Reaction Mix: Assemble a standard 25 µL reaction containing:

- Thermocycling with Gradient Annealing:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–5 minutes.

- Amplification (35–40 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15–30 seconds.

- Anneal: Use a temperature gradient (e.g., 55°C to 65°C) for 15–30 seconds. The optimal annealing temperature (T~a~) is typically 5°C below the primer T~m~ [3].

- Extend: 72°C for 15–60 seconds per 500 bp.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Analysis:

- Analyze PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- The optimal T~a~ is the highest temperature that yields a single, bright amplicon of the expected size with no primer-dimer bands.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Primer Design and Validation

| Tool or Reagent | Function / Description | Example Products / Software |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Software | Generates candidate primer sequences based on user-defined parameters. | Primer3 [25], Geneious [24], IDT PrimerQuest Tool [3] |

| Oligo Analysis Suite | Analyzes T~m~, secondary structures (hairpins, dimers), and specificity. | IDT OligoAnalyzer [3], UNAFold Tool [3] |

| Sequence Alignment Tool | Align multiple sequences to find conserved regions for degenerate primer design. | MAFFT [24], varVAMP (for viral pathogens) [25] |

| Specificity Check Tool | Verifies primer uniqueness against genomic databases to prevent off-target binding. | NCBI BLAST [3] [20] |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by requiring heat activation. | DreamTaq Hot Start Polymerase [24] |

| Gradient Thermocycler | Empirically determines the optimal annealing temperature in a single run. | Various manufacturers (e.g., Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher) |

Meticulous primer design is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of PCR success. By systematically applying the core rules of length, T~m~, and GC content, researchers can significantly minimize the risks of secondary structures and non-specific amplification. The experimental protocols and tools outlined here provide a robust framework for developing highly specific and efficient PCR assays, thereby ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of results in both research and diagnostic applications.

In polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays, primers are the linchpin of success. Among the numerous design considerations, the sequence and structural integrity of the primer's 3' end stand apart as non-negotiable factors for achieving specific and efficient amplification. Self-complementarity at the 3' end, which can lead to the formation of hairpin structures or primer-dimers, directly compromises the primer's ability to faithfully anneal to the intended template sequence. This application note, framed within our broader thesis on robust primer design, details the critical reasons behind this principle and provides validated protocols to ensure your primers meet this essential criterion. The presence of a stable hairpin at the 3' end can sequester the very region where DNA polymerase must bind and initiate synthesis, leading to failed reactions, reduced sensitivity, and false results [26] [27]. We will demonstrate that rigorous computational screening and thermodynamic validation of the 3' end are not mere suggestions but fundamental requirements for reliable assay development.

The Core Principle: Thermodynamic and Biochemical Imperatives

The Polymerase Starting Gate

The biochemical rationale for protecting the 3' end is straightforward and critical. The DNA polymerase enzyme binds at the 3'-OH end of the primer to initiate the synthesis of a new DNA strand [16]. Any secondary structure that involves the 3' end, even a few bases, can physically block the polymerase from binding or extending. This is particularly detrimental because these structures form intra-molecularly, effectively competing with the primer's intended intermolecular binding to the template DNA. A self-complementary 3' end creates a "selfish" primer that is more likely to fold back on itself than to hybridize with the target sequence.

Quantifying the Risk: Thermodynamic Stability of Secondary Structures

The stability of a hairpin structure is quantitatively described by its change in Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG). A more negative ΔG value indicates a more stable and spontaneously forming structure [16]. While some internal hairpins may be tolerated if their ΔG is more positive than -3 kcal/mol, the rules are far stricter for the 3' end.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Tolerance for Primer Secondary Structures

| Structure Type | Description | Maximum Tolerated Stability (ΔG) | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3' End Hairpin | Hairpin involving the terminal 3' bases [16] | > -2 kcal/mol | Prevents polymerase binding and initiation. Most critical to avoid. |

| Internal Hairpin | Hairpin located away from the 3' terminus [16] | > -3 kcal/mol | Can slow hybridization but may be tolerated if less stable. |

| Self-Dimer | Dimer between two identical primers [3] | > -9 kcal/mol | Reduces free primer concentration, can lead to spurious amplification. |

| Cross-Dimer | Dimer between forward and reverse primers [3] | > -9 kcal/mol | Can deplete both primers and generate primer-dimer artifacts. |

Research indicates that if the calculated ΔG of a 3' hairpin is more negative than -2 kcal/mol, it is highly likely to impede hybridization and PCR efficiency [16]. Furthermore, a hairpin with a melting temperature (Tm) at or above your assay's annealing temperature is particularly problematic, as it will not "melt out" under reaction conditions, permanently sequestering the primer [27].

Impact on Assay Performance and Data Fidelity

The consequences of 3' end self-complementarity extend beyond failed amplification. In qPCR and reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP), these structures cause a slowly rising baseline fluorescence due to non-specific amplification and the generation of double-stranded primer extension products [26]. This depletes reaction components, reduces amplification efficiency for the true target, and compromises the accuracy of quantification, leading to both false positives and false negatives.

Experimental Protocol: Detection and Validation

In silico Analysis of Primer Secondary Structures

Purpose: To bioinformatically screen designed primer sequences for stable secondary structures, particularly at the 3' end, prior to synthesis.

Materials:

- Computer with internet access

- Primer sequences in FASTA or plain text format

Method:

- Sequence Input: Navigate to the IDT OligoAnalyzer Tool. Enter a single primer sequence into the input box.

- Hairpin Analysis: Select the "Hairpin" analysis tab. Set the reaction parameters to match your intended PCR conditions as closely as possible, including Na+ (e.g., 50 mM) and Mg++ (e.g., 1.5-3 mM) concentrations [28]. The annealing temperature is a critical parameter.

- Data Interpretation: The tool will generate a list of possible hairpin structures.

- Identify any structure where the 3' terminal bases are involved in the hybridized stem.

- Note the ΔG value for this structure. If ΔG ≤ -2 kcal/mol, the primer carries a high risk of failure [16].

- Compare the hairpin's Tm to your planned annealing temperature. If the hairpin Tm ≥ Ta, the structure will not denature and will likely cause failure [27].

- Self-Dimer Check: Return to the "Analyze" tab and select "Self-Dimer." Examine the output for stable dimers (ΔG < -9 kcal/mol), paying special attention to interactions involving the 3' ends.

Troubleshooting: If a stable 3' hairpin is identified, proceed to Section 4.0 (Troubleshooting and Primer Correction) to re-design the primer.

Empirical Validation by Melt Curve and Gel Electrophoresis

Purpose: To experimentally confirm the specificity of primers and the absence of primer-dimer artifacts after in silico screening.

Materials:

- Synthesized, desalted primers

- Standard PCR or qPCR master mix (e.g., containing SYBR Green dye for qPCR)

- Thermal cycler or real-time PCR instrument

- Equipment for agarose gel electrophoresis

Method:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a standard PCR or qPCR reaction mix according to your protocol. Include a non-template control (NTC) containing water instead of DNA/cRNA template [29].

- Amplification: Run the PCR/qPCR protocol. For qPCR, ensure the instrument is set to acquire a melt curve after amplification.

- Melt Curve Analysis: Analyze the melt curve of the NTC. A single, sharp peak at a low temperature (e.g., 75-80°C) often indicates primer-dimer formation. A clean NTC with no peak, or a very small, late-appearing peak, suggests specific primers [29].

- Gel Electrophoresis: If using standard PCR, analyze the NTC and test samples on a 1.5–2.5% agarose gel. A single, discrete band of the expected size in the sample lane and a clean NTC lane confirm primer specificity [29]. A smeared or extra band in the NTC lane indicates significant non-specific amplification due to primer secondary structures.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Design Software (e.g., Primer-Blast, PrimerQuest) [29] [3] | Generates candidate primer sequences from a template with customizable parameters (Tm, GC%, length). | Ensures initial candidates meet basic design rules before deep secondary structure analysis. |

| Oligo Analysis Tool (e.g., IDT OligoAnalyzer) [3] [27] | Calculates Tm, ΔG of hairpins and self-dimers for a given sequence under specific salt conditions. | Critical for evaluating 3' end stability. Use your exact reaction buffer conditions for accuracy. |

| SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and a fluorescent dye that intercalates into dsDNA. | The dye will fluoresce upon binding any dsDNA, including primer-dimer products, revealing non-specificity. |

| Bst DNA Polymerase | Recombinant enzyme for isothermal amplification (e.g., LAMP) [26]. | Often used in point-of-care assays; also susceptible to inhibition by primer secondary structures. |

Troubleshooting and Primer Correction

When screening identifies a problematic primer, follow this logical workflow to correct the issue.

Specific Actions:

- Shift the Primer Sequence: The most effective solution is often to shift the primer binding site 1-3 bases upstream or downstream on the template sequence. This minor shift can completely disrupt the self-complementary region while maintaining the primer's specificity and desired Tm [28].

- Modify the 3' End: If shifting is not possible, consider substituting one of the 3' terminal bases. A single base change can be sufficient to break a stable hairpin. When doing this, ensure the new 3' end does not create a mismatch with the template and maintains a G or C residue for strong anchoring (a "GC clamp") if possible, but avoid creating a run of more than 3 G/C bases [30] [20].

- Re-run Analysis: After any modification, the new sequence must be put through the same in silico analysis (Section 3.1) to confirm the problem has been resolved.

The imperative to avoid self-complementarity at the primer's 3' end is rooted in the fundamental biochemistry of DNA synthesis. Allowing this single flaw to persist can invalidate the painstaking work of assay development and compromise scientific conclusions. By integrating the computational screening and empirical validation protocols outlined in this document into your standard primer design workflow, you can systematically eliminate this source of error. Ensuring your primers have a clean, linear 3' end is a non-negotiable step toward achieving robust, reproducible, and accurate molecular results.

Within the framework of a thesis on best practices for designing primers to avoid hairpins, the strategic use of specialized software is a critical step toward ensuring assay specificity and efficiency. Hairpin structures, formed by intramolecular base-pairing within a single primer, can severely hinder the primer's ability to bind to its target template, leading to PCR failure or reduced yield [31] [13]. While in silico predictions are not a complete substitute for empirical optimization, they provide a powerful first line of defense against these detrimental secondary structures. This application note details protocols for leveraging three key tools—Geneious Prime, NCBI's Primer-BLAST, and IDT's resources—to integrate automated checks for hairpins and other common pitfalls directly into the primer design and validation workflow.

Tool-Specific Primers and Protocols

Geneious Prime for Integrated Design and Validation

Geneious Prime offers a unified environment for designing primers and automatically evaluating their characteristics, including hairpin formation, self-dimerization, and melting temperature (Tm).

Experimental Protocol: Designing and Checking Primers in Geneious

1. Design New Primers: Select your target sequence and navigate to Primers → Design New Primers. In the design dialog, configure the parameters for your assay, such as the product size range and the target region [32] [33].

2. Set Hairpin and Dimer Checks: Within the Characteristics panel, the software automatically calculates and applies penalties to primers based on their potential to form hairpins and self-dimers. The algorithm considers the stability (ΔG) and melting temperature of these secondary structures [33]. Users can adjust the Primer Picking Weights to increase the stringency of these checks, thereby assigning a higher penalty to primers with unfavorable characteristics [33].

3. Validate with Saved Primers: To test pre-existing primers against a new template, use Primers → Test with Saved Primers. This function annotates the primer binding sites on the target sequence and allows you to inspect for mismatches, particularly near the 3' end, which is critical for amplification [32].

4. Interpret Results: Primers are annotated on the sequence in green. Hovering over a primer annotation displays a tooltip with key characteristics. Examine the calculated hairpin and dimer scores, and prioritize primers with minimal secondary structure formation [32].

Table: Key Primer Design Parameters and Recommendations in Geneious Prime

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18-27 bases [32] | Balances specificity and binding efficiency. |

| Melting Temp (Tm) | 50-65°C [32] | Ensures efficient annealing during PCR cycles. |

| Tm Difference (Pair) | ≤ 4°C [32] | Ensures both primers anneal at the same temperature. |

| GC Content | 40-60% [32] | Provides stable binding; avoids rich AT/GC regions. |

| Hairpin Formation | Minimize (Software calculated) | Prevents self-hybridization that blocks binding. |

NCBI Primer-BLAST for Specificity Checking

NCBI's Primer-BLAST is uniquely powerful because it combines primer design with a specificity check using the BLAST algorithm, ensuring your primers amplify only the intended target.

Experimental Protocol: Designing Specific Primers with Primer-BLAST

1. Input Template: Go to the Primer-BLAST submission form. Enter your template sequence as an accession number or in FASTA format [6] [34].

2. Set Specificity Parameters: In the Primer Pair Specificity Checking Parameters section, select the organism and the database against which to check specificity (e.g., Refseq mRNA). This restricts the BLAST search to ensure primers are unique to your target of interest [6] [34].

3. Adjust Algorithm Parameters (if checking pre-designed primers): When using the tool to check the specificity of existing primers, you can adjust BLAST parameters for short sequences. As per IDT's tips, decrease the word size to 7, increase the expect threshold to 1000, and turn off the low complexity filter to ensure your short primers are properly detected [35].

4. Retrieve and Analyze Results: Primer-BLAST returns candidate primer pairs that are predicted to amplify your specific template. The results show the location of the primers and the expected product size. Crucially, it also displays a detailed list of any other potential targets in the selected database, allowing you to verify that off-target amplification is unlikely [6] [34].

Table: Primer-BLAST Database Selection Guide

| Database | Best Use Case | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Refseq mRNA | RT-PCR from a specific organism | Contains curated, non-redundant mRNA sequences. |

| Refseq Representative Genomes | Genomic DNA amplification | High-quality, minimally redundant genome collection. |

| nr | Broadest specificity check | Comprehensive but slower; may contain redundancies. |

| core_nt | Faster broad check | Similar to 'nr' but excludes large eukaryotic chromosomes. |

IDT's Approach for Quick Specificity Analysis

Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) provides expert tips for using BLAST to check the specificity of pre-designed primer pairs and predict the resulting amplicon.

Experimental Protocol: BLAST-Based Primer Checking with IDT's Method

1. Prepare Primer Query: Concatenate your forward and reverse primer sequences into a single sequence, separating them with 5–10 N bases to represent any sequence [35].

2. Configure BLAST Search: Navigate to NCBI's standard Nucleotide BLAST (not Primer-BLAST). Paste the concatenated sequence into the query box. Before submitting, narrow the search by selecting the relevant organism or a specific database like refseq_mRNA [35].

3. Optimize for Short Sequences: In the Algorithm parameters section, make the following critical adjustments for short primer queries:

- Set Word size to 7.

- Increase Expect threshold to 1000.

- Turn off the Low complexity filter [35].

4. Execute and Interpret: Run the BLAST search. In the results, a single line connecting two boxes indicates that both primers are found on the same transcript or genomic sequence in the correct orientation. Clicking on this result reveals their precise locations and the length of the expected PCR product [35].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and digital tools used in the primer design and validation workflow.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Digital Tools for Primer Design

| Item/Tool | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Geneious Prime | Integrated bioinformatics software for primer design, sequence analysis, and annotation. | Uses Primer3 algorithm to automatically calculate Tm, GC%, hairpins, and self-dimers [32] [33]. |

| NCBI Primer-BLAST | Web tool that designs primers or checks specificity of existing primers using BLAST. | Ensures primers are specific to the intended target sequence, preventing off-target amplification [6] [34]. |

| OligoAnalyzer Tool (IDT) | Online tool for analyzing oligonucleotide properties. | Useful for checking secondary structures (hairpins, dimers) and Tm of individual primer sequences post-design [35]. |

| Template DNA Sequence | High-quality, accurately sequenced DNA of the target region. | The foundation of all design work; inaccuracies here propagate to faulty primer design. |

| DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for PCR amplification (e.g., standard Taq, high-fidelity enzymes). | Different polymerases may have optimal Tm requirements; consult manufacturer protocols for annealing temperature guidelines. |

Automated primer checking using software tools is an indispensable practice in modern molecular biology. As detailed in these protocols, Geneious Prime provides an all-in-one suite for design and initial validation, NCBI Primer-BLAST is unparalleled for ensuring target specificity, and IDT's refined BLAST technique offers a rapid method for confirming primer binding and predicting amplicons. By systematically integrating these tools into a cohesive workflow—designing with appropriate parameters, rigorously checking for hairpins and self-dimers, and finally verifying specificity against comprehensive databases—researchers can significantly de-risk the experimental process. This structured, software-assisted approach lays a robust foundation for successful PCR assays, directly supporting the overarching thesis goal of establishing best practices for designing primers free of problematic secondary structures.