Analyzing Variance in Pharmaceutical Analysis: A Practical Guide to Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Method Comparison

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, investigate, and troubleshoot variance between spectrophotometric and chromatographic analytical results.

Analyzing Variance in Pharmaceutical Analysis: A Practical Guide to Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Method Comparison

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, investigate, and troubleshoot variance between spectrophotometric and chromatographic analytical results. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, optimization strategies, and formal validation protocols, it synthesizes current best practices and regulatory guidelines. The content is designed to aid in the selection of appropriate analytical techniques, enhance data reliability, and ensure robust method performance for quality control and pharmaceutical development.

Core Principles: Understanding Spectrophotometry and Chromatography in Pharmaceutical Analysis

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring drug quality, safety, and efficacy hinges on robust analytical methods. Spectrophotometry and chromatography represent two foundational pillars of analytical technique, yet they operate on fundamentally different principles. Spectrophotometry primarily involves the interaction of light with molecules to obtain quantitative data, while chromatography relies on the physical separation of mixture components before detection. Within the context of analytical research, understanding the variance between their results is not merely an academic exercise but a critical practice for validating methods, interpreting data correctly, and ensuring regulatory compliance. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these techniques, supported by experimental data and protocols, to aid researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and validating the appropriate analytical tool for their specific applications.

Core Principles and Instrumentation

Spectrophotometry: Probing Molecules with Light

Spectrophotometry is a technique that measures how much a chemical substance absorbs or transmits light. When a molecule is exposed to a beam of light, it can absorb specific wavelengths that correspond to the energy required to promote electrons to higher energy states. The fundamental relationship is described by the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to its concentration and the path length of the light through it. A typical UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of a light source, a monochromator to select specific wavelengths, a sample holder, and a photodetector to measure the intensity of the transmitted light. The resulting spectrum provides information on the sample's concentration and, to some extent, its structural properties.

Chromatography: Separating to Clarify

Chromatography, in contrast, is a separation technique. It involves passing a mixture dissolved in a mobile phase through a stationary phase. Components in the mixture separate based on their differential partitioning between the two phases. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), a widely used form, utilizes a high-pressure pump to move the mobile phase and sample through a column packed with the stationary phase. The separated components then elute from the column at different times, known as retention times, and are directed to a detector. The detector, which can be a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, generates a signal proportional to the concentration of each component, producing a chromatogram. Thus, while chromatography often uses light interaction for detection, its primary analytical power comes from the initial physical separation [1].

Comparative Experimental Analysis: Repaglinide Assay

A direct comparison can be drawn from a study that developed and validated both UV-Spectrophotometric and Reversed-Phase HPLC (RP-HPLC) methods for the determination of Repaglinide, an antidiabetic drug, in tablet dosage forms [1]. The following sections detail the protocols and results, highlighting the operational and performance differences.

Experimental Protocols

- Instrumentation: Double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu 1700) with 1.0 cm quartz cells.

- Standard Solution Preparation: A stock solution of Repaglinide (1000 µg/mL) was prepared in methanol. Working standard solutions were prepared by diluting the stock with methanol to a concentration range of 5–30 µg/mL.

- Sample Preparation: Twenty tablets were weighed and finely powdered. A portion equivalent to 10 mg of Repaglinide was dissolved in methanol, sonicated for 15 minutes, and diluted to volume. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was further diluted with methanol to a concentration within the linearity range.

- Analysis: The absorbance of the standard and sample solutions was measured at a wavelength of 241 nm against a methanol blank.

- Instrumentation: HPLC system (e.g., Agilent 1120 Compact LC) with a UV detector and a C18 column (Agilent TC-C18, 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm).

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Mobile Phase: Methanol and water in a ratio of 80:20 v/v, with pH adjusted to 3.5 using orthophosphoric acid.

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection Wavelength: 241 nm.

- Injection Volume: 20 µL.

- Standard & Sample Preparation: Stock and sample solutions were prepared similarly to the spectrophotometric method, but final dilutions were made using the mobile phase. The concentration range for the calibration curve was 5–50 µg/mL.

Workflow and Logical Relationship

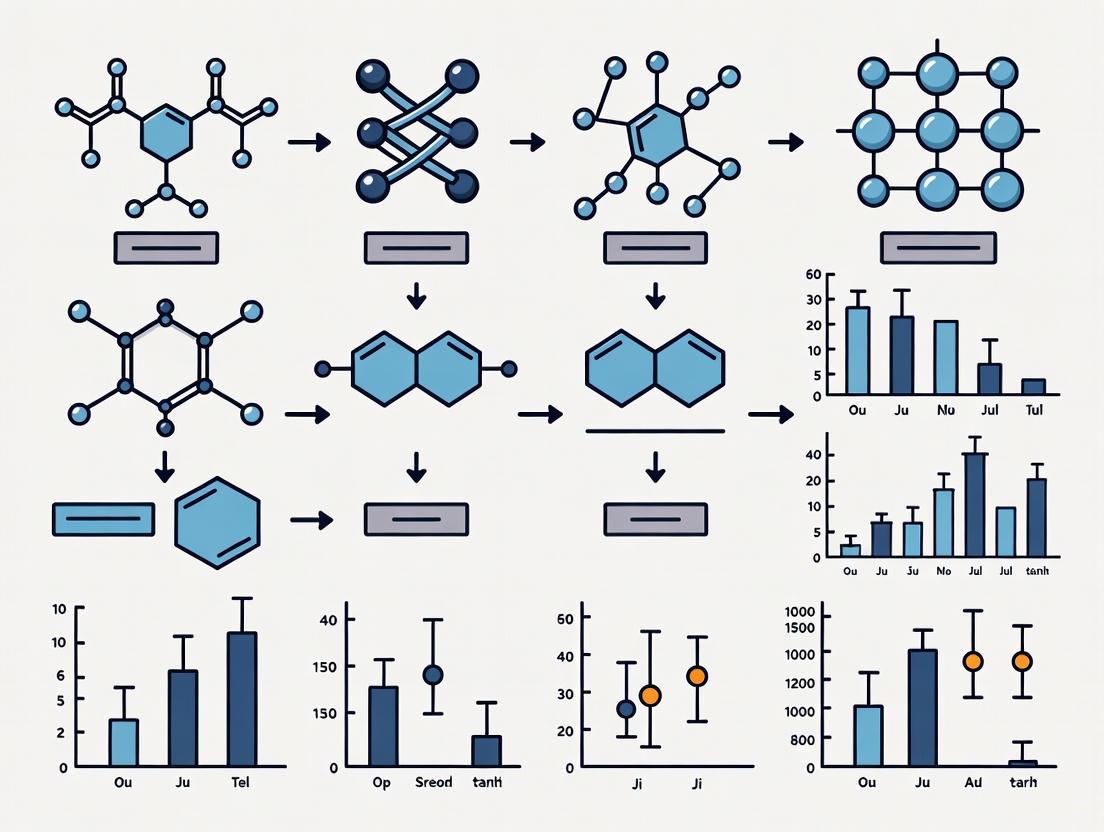

The diagram below illustrates the logical pathways and key decision points for selecting and applying spectrophotometric versus chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis.

Performance Data Comparison

The methods were validated as per International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, and the following performance characteristics were documented [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Validation Parameters for Repaglinide Assay

| Validation Parameter | UV-Spectrophotometry | RP-HPLC |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range | 5–30 µg/mL | 5–50 µg/mL |

| Regression Coefficient (r²) | >0.999 | >0.999 |

| Precision (% R.S.D.) | <1.50% | <1.50% (but generally higher than UV) |

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | 99.63–100.45% | 99.71–100.25% |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) & Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Calculated via standard formulae, but generally higher than HPLC | Calculated via standard formulae, offering lower LOD/LOQ |

Table 2: Practical and Operational Characteristics

| Characteristic | UV-Spectrophotometry | RP-HPLC |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Principle | Light absorption | Physical separation + detection |

| Key Instrumentation | Spectrophotometer, cuvettes | Pump, column, detector (e.g., UV) |

| Sample Throughput | High (fast analysis) | Lower (longer run times per sample) |

| Specificity | Low (measures total absorbance) | High (separates components) |

| Cost & Complexity | Lower cost, simpler operation | Higher cost, requires skilled operation |

| Ideal Application | Quantitative analysis of pure compounds or simple mixtures | Quantitative analysis of complex mixtures; impurity profiling |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful method development relies on high-quality materials and reagents. The following table lists key items used in the featured experiments and their general functions in analytical chemistry.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectrophotometry and HPLC

| Item | Function / Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Reference Standard | Highly purified analyte used to prepare calibration solutions and validate the method's accuracy. |

| HPLC-Grade Methanol | Common solvent and mobile phase component; its high purity prevents UV absorption interference and column damage. |

| HPLC-Grade Water | Essential mobile phase component; purified to remove ions and organics that could cause baseline noise or contamination. |

| Orthophosphoric Acid | Used to adjust the pH of the mobile phase, which can critically alter the retention time, selectivity, and peak shape in HPLC. |

| C18 Chromatography Column | The stationary phase for RP-HPLC; separates components based on their hydrophobicity. |

| Ultrasonic Bath | Used to dissolve samples and degas solvents to prevent air bubbles that interfere with spectrophotometric readings or HPLC pressure. |

| Syringe Filters | Used to clarify sample solutions by removing particulate matter that could damage the HPLC column or scatter light in the spectrophotometer. |

Advanced Techniques and Future Directions

Handling Complex Mixtures with Advanced Spectrophotometry

For complex mixtures where components have overlapping spectra, simple univariate spectrophotometry is insufficient. Advanced chemometric techniques like Partial Least Squares (PLS) and Principal Component Regression (PCR) can be employed. These multivariate models deconvolute the spectral data from a mixture to quantify individual analytes, even in the presence of a toxic impurity, as demonstrated in a study analyzing Oxytetracycline, Lidocaine, and its carcinogenic impurity, 2,6-dimethylaniline [2]. While powerful, these methods require complex calibration and validation.

The Push for Green and Quality-by-Design (QbD) Methods

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly integrating Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles with a Quality-by-Design (QbD) framework for method development [3]. QbD is a systematic approach that emphasizes building quality into the analytical method from the start by defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and using risk assessment and Design of Experiments (DoE) to understand the method's robustness. This aligns with GAC's goal of reducing hazardous waste, energy consumption, and the use of toxic reagents. The synergy of QbD and GAC leads to the development of analytical methods that are not only reliable and robust but also environmentally sustainable [3].

Both spectrophotometry and chromatography are indispensable in the analytical scientist's arsenal, but they serve different purposes. As the experimental data shows, UV-spectrophotometry is a rapid, cost-effective tool for quantifying analytes in simple matrices. In contrast, HPLC provides superior specificity and resolution for complex mixtures, making it the gold standard for impurity profiling and assays in drug development. The choice between them hinges on the sample's complexity and the required specificity. The ongoing integration of QbD and GAC principles is shaping the future of both techniques, driving the development of methods that are not only scientifically sound but also environmentally responsible and economically viable.

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical development and environmental monitoring, the reliability of analytical data is paramount. Accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity are fundamental performance characteristics that validate an analytical method, ensuring it is fit for its intended purpose [4] [5]. These Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) form the backbone of method validation, providing objective evidence that a procedure consistently produces results that are reliable, reproducible, and meaningful [6].

The comparison between spectrophotometric and chromatographic techniques provides a compelling framework for understanding these KPIs. While UV-Vis spectrophotometry is often praised for its operational simplicity and cost-effectiveness, chromatographic methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are recognized for their superior resolving power [7] [8]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these techniques within the context of a broader thesis on analyzing variance between spectrophotometric and chromatographic results, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data necessary to make informed methodological choices.

Defining the Core Performance Indicators

Accuracy

Accuracy is defined as the closeness of agreement between a measured value and a value accepted as either a conventional true value or an established reference value [5]. It is typically reported as a percentage recovery of a known amount of analyte or as the difference between the mean and the accepted true value along with confidence intervals [5]. In practice, accuracy demonstrates that a method correctly measures the analyte it claims to measure.

Precision

Precision expresses the closeness of agreement (degree of scatter) between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions [5]. It is usually evaluated at three levels:

- Repeatability: Precision under the same operating conditions over a short time interval [5].

- Intermediate Precision: Variations within the same laboratory (different days, analysts, equipment) [5].

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories, crucial for method standardization [5].

Specificity

Specificity is the ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradation products, and matrix components [4]. A specific method can distinguish and quantify the analyte from interferences, which is particularly critical for stability-indicating methods. The term is often used interchangeably with selectivity, though a subtle distinction exists: a 'specific' method responds only to a single analyte, while a 'selective' method provides responses for a number of chemical entities that can be distinguished from each other [4].

Linearity

Linearity of an analytical method is its ability to elicit test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample within a given range [5]. It is demonstrated by the capacity of the method to obtain a signal that is directly proportional to the analyte's concentration. The relationship is typically evaluated using statistical methods, with the calculation of a regression line by the method of least squares, and is foundational for establishing the method's quantitative capacity [5].

Comparative Experimental Data: Spectrophotometry vs. Chromatography

The following table summarizes quantitative performance data for spectrophotometric and chromatographic methods from controlled studies, particularly in the analysis of emerging contaminants and pharmaceutical compounds.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Emerging Contaminant Analysis

| Analyte | Technique | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Performance Findings | Reference Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caffeine (CAF) | Electroanalytic (BDD sensor) | 0.69 mg L⁻¹ | Strong resolving power; excellent precision and accuracy; low reagent consumption [7] | Synthetic effluents, environmental water [7] |

| Caffeine (CAF) | HPLC (Reference method) | - | Reliable but expensive instrumentation and maintenance [7] | |

| Paracetamol (PAR) | Electroanalytic (BDD sensor) | 0.84 mg L⁻¹ | Effective for complex matrices (tap, ground, lagoon water) [7] | Synthetic effluents, environmental water [7] |

| Methyl Orange (MO) | Electroanalytic (BDD sensor) | 0.46 mg L⁻¹ | Time-efficient analysis compared to reference methods [7] | Synthetic effluents, environmental water [7] |

| Sucralose | Chromatographic Methods | Micro/Nanomolar levels | Considered dominant for accurate determination in food/environmental samples [8] | Food, environmental objects [8] |

| Sucralose | Spectrophotometric Methods | Frequently higher | Often used as complementary to chromatographic methods to sensitize them [8] | |

| Atorvastatin & Ezetimibe | Dual Wavelength Spectrophotometry | - | Accurate, precise, and economic; successful for combined dosage forms [9] | Pharmaceutical dosage form [9] |

Table 2: KPI Performance Profile by Technique

| Performance Indicator | Spectrophotometric Methods | Chromatographic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Can be compromised by spectral interferences from transformation intermediates or matrix components [7] | High accuracy due to superior separation, reducing matrix interference [7] [8] |

| Precision | Satisfactory for standard solutions; susceptible to variation in complex matrices [9] | High precision and reproducibility, validated through rigorous intra- and inter-laboratory studies [4] |

| Specificity | Lower; severe spectral overlap in mixtures requires sophisticated processing (e.g., mean centering) [9] | High; core strength lies in physically separating analytes from interferents before detection [7] [8] |

| Linearity | Demonstrable over a defined range, but may require mathematical processing for mixtures [9] | Wide dynamic range, with linearity easily demonstrated and validated for single analytes [4] [5] |

| Applicability | Ideal for simple, binary mixtures and routine quality control where cost and speed are critical [9] | Preferred for complex mixtures (e.g., drug purity, environmental tracers), impurity profiling, and regulatory submission [10] [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Simultaneous Spectrophotometric Assay

A study on the simultaneous determination of Atorvastatin calcium (ATR) and Ezetimibe (EZ) in a combined tablet dosage form provides a robust protocol for a spectrophotometric method [9].

- Methodology: Two spectrophotometric methods were employed: Dual Wavelength Analysis and Mean Centering of Ratio Spectra (MCR) [9].

- Sample Preparation: Standard stock solutions of ATR and EZ (1 mg/mL) were prepared in methanol. Working solutions (0.1 mg/mL) were then diluted to concentrations within the linearity range (60–260 μg/mL for ATR and 4–40 μg/mL for EZ) [9].

- Dual Wavelength Analysis: Wavelengths were selected where the difference in absorbance was zero for the interfering drug. For ATR, wavelengths 226.6 nm and 244 nm (where EZ has equal absorbance) were used. For EZ, wavelengths 228.6 nm and 262.8 nm (where ATR has equal absorbance) were used. The difference in absorbance at the selected pair of wavelengths was plotted against concentration for quantification [9].

- MCR Method: The absorption spectra of different concentrations were recorded (200–350 nm), divided by the spectrum of a suitable divisor of the other drug, and the resulting ratio spectra were mean-centered. The concentrations were determined from the calibration graphs obtained by measuring the amplitudes at 215–260 nm [9].

- Validation: The methods were tested for accuracy and precision, with recovery studies confirming accuracy. Selectivity was confirmed using synthetic mixtures of the drugs in different ratios [9].

Protocol: Chromatographic Analysis of Emerging Contaminants

A comparative study of operational approaches for quantifying emerging contaminants (ECs) like caffeine, paracetamol, and methyl orange outlines a standard chromatographic protocol [7].

- Methodology: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) was used as a reference method against which electroanalytic techniques were compared [7].

- Sample Preparation: Stock solutions of ECs (100 mg L⁻¹ for CAF and PAR, 50 mg L⁻¹ for MO) were prepared in an acidic and neutral medium (0.5 mol L⁻¹ H₂SO₄ and 0.5 mol L⁻¹ Na₂SO₄). Model EC waste solutions (20 mg L⁻¹ for CAF and PAR, 10 mg L⁻¹ for MO) were used in treatment experiments [7].

- Analysis and Validation: The concentration of ECs was monitored during electrochemical oxidation tests. The performance of HPLC was benchmarked in terms of its reliability and the confidence it provides, albeit with higher operational costs and more complex sample pretreatment compared to electroanalytic methods [7].

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting and validating an analytical technique based on the four key performance indicators.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting the validated experiments discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Analytical Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Sensor | Electroanalytic sensor with strong resolving power for voltammetric analysis of contaminants [7] | Quantifying caffeine, paracetamol, and methyl orange in environmental water samples [7] |

| Reference Standards (e.g., Caffeine, Paracetamol) | Pure substances of known identity and purity used to prepare calibration curves and assess accuracy [5] | Method development and validation for drug substance/drug product assays [5] |

| HPLC-Grade Methanol | High-purity solvent used for preparing mobile phases, standard solutions, and sample extracts to minimize background interference [9] | Solvent for dissolving Atorvastatin and Ezetimibe in spectrophotometric analysis [9] |

| Synthetic Matrix | A mixture of all drug product components except the analyte, used for spiking studies to demonstrate accuracy in complex formulations [5] | Accuracy testing for drug product assays where the complete sample matrix is difficult to obtain [5] |

| Stationary Phases (C18, etc.) | The solid phase in chromatography columns that separates analytes based on their chemical properties [4] | Achieving resolution (Rs > 2) between target analytes and potential interferents in HPLC [4] |

The comparative analysis of spectrophotometry and chromatography through the lens of accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity reveals a clear paradigm: the choice of an analytical technique is a strategic trade-off. Spectrophotometry offers a cost-effective and rapid solution for well-defined, simple matrices. In contrast, chromatography provides superior specificity and reliability for complex samples, which is indispensable in regulated environments and for challenging applications like impurity profiling or environmental tracer studies [7] [8] [9].

The experimental data and protocols presented provide a framework for researchers to make evidence-based decisions. Ultimately, validating a method against these four core KPIs is not merely a regulatory hurdle but a fundamental scientific practice that ensures the integrity of data and the safety and efficacy of final products, from pharmaceuticals to our shared environment.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the reliability of analytical data is paramount, ensured through a rigorous process known as method validation. Method validation is the documented process of proving that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended use, consistently producing reliable, accurate, and reproducible results that safeguard pharmaceutical integrity and patient safety [11]. This process is mandated by global regulatory agencies for all submissions (NDAs/ANDAs/BLAs) to ensure product quality, identity, purity, and potency [12].

Three major regulatory bodies provide the primary frameworks for these activities: the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the United States Pharmacopeia (USP), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The ICH Q2(R1) guideline, "Validation of Analytical Procedures," serves as the international benchmark, defining key validation parameters and scientific approaches [12] [11]. The USP provides legally recognized standards in the United States, detailing requirements in general chapters like <1225> "Validation of Compendial Procedures" [12]. The FDA enforces application requirements, emphasizing a systematic, risk-based approach that aligns with ICH principles [12]. Understanding the similarities and variances between these guidelines is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to ensure global compliance and data integrity.

Comparative Analysis of ICH, USP, and FDA Guidelines

While the ICH, USP, and FDA guidelines share the common goal of ensuring analytical data quality, they differ in focus, global applicability, and specific requirements. The following table provides a structured comparison of these key guidelines.

| Feature/Aspect | ICH Q2(R1) | USP General Chapter <1225> | FDA Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus & Scope | Provides a harmonized, scientific framework for validating analytical procedures; defines core validation characteristics [12]. | Categorizes analytical procedures and specifies validation requirements based on the test type (e.g., assay, impurity test) [12]. | Emphasizes a systematic, risk-based development and validation process to ensure product quality [12]. |

| Global Applicability | International (adopted across ICH regions: EU, Japan, USA, etc.) [11]. | Primarily for users of the United States Pharmacopeia, though influential globally [11]. | United States; however, its principles are often referenced internationally [11]. |

| Core Validation Parameters | Specificity, Linearity, Range, Accuracy, Precision (Repeatability, Intermediate Precision), LOD, LOQ [13]. | Aligns with ICH but structures requirements by procedure category (I-IV). Includes Robustness and Ruggedness explicitly [13]. | Aligns with ICH Q2(R1), stressing specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, LOD, LOQ, and robustness [12]. |

| Categorization of Methods | Does not formally categorize methods. | Category I: Assays (quantitative for API)Category II: Impurity tests (quantitative and limit tests)Category III: Performance tests (e.g., dissolution)Category IV: Identification tests [12]. | Does not formally categorize methods but acknowledges compendial categories (USP) [12]. |

| Robustness & Ruggedness | Robustness is considered part of method development and is encouraged but is not a mandatory validation parameter [13]. | Explicitly lists Robustness (capacity to remain unaffected by small parameter variations) and Ruggedness (reproducibility under varied conditions) as validation parameters [13]. | Strongly emphasizes robustness testing as part of a risk-based assessment, often via Design of Experiments (DoE) [12]. |

| System Suitability | Considered an integral part of chromatographic methods but is addressed separately from the validation parameters list [13]. | Dealt with in a separate general chapter (e.g., USP <621>) and is a required test before and during analytical runs [13]. | Requires system suitability testing to ensure the validity of the analytical system at the time of testing [14]. |

A critical conceptual relationship exists between these guidelines. The following diagram illustrates how ICH Q2(R1) serves as the foundational scientific framework, which is then operationalized for specific compendial tests by USP and enforced with a risk-management focus by the FDA.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

The practical application of these guidelines is demonstrated through experimental validation of analytical methods. The following workflow outlines the typical stages from development through validation, incorporating elements from ICH, USP, and FDA expectations.

Case Study: UV and HPLC Methods for Repaglinide

A 2012 study provides a direct comparison of a UV-Spectrophotometric method and a Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) method for determining repaglinide in tablets, validating both as per ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [1]. This case study is particularly relevant for analyzing variance between spectrophotometric and chromatographic results.

Methodology and Experimental Protocols:

- Instrumentation and Materials: The study used a Shimadzu 1700 UV-Vis spectrophotometer and an Agilent 1120 Compact LC system with a C18 column. The solvent and mobile phase for both methods was methanol and water [1].

- UV-Spectrophotometric Method:

- Protocol: A standard stock solution of repaglinide (1000 µg/ml) was prepared in methanol. Aliquots were diluted with methanol to concentrations of 5-30 µg/ml. The absorbance of these solutions was measured at 241 nm against a methanol blank, and a calibration curve of concentration versus absorbance was plotted [1].

- RP-HPLC Method:

- Protocol: The mobile phase was methanol and water (80:20 v/v, pH adjusted to 3.5 with orthophosphoric acid) at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Detection was at 241 nm. Standard solutions (5-50 µg/ml) were prepared in the mobile phase, and 20 µl was injected. The peak area was plotted against concentration to construct the calibration curve [1].

- Validation Procedure: Both methods were validated for the following parameters as per ICH Q2(R1) [1]:

- Linearity: Six standard solutions were analyzed in triplicate.

- Precision: Repeatability (six analyses at 100% concentration) and intra- & inter-day precision were evaluated.

- Accuracy: Determined by standard addition recovery experiments at three concentration levels.

- LOD and LOQ: Calculated based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve.

- Specificity: Assessed by evaluating possible interference from tablet excipients.

- Ruggedness: Determined by analyzing samples under varied conditions (different time intervals, days, analysts).

Results and Comparative Data: The quantitative results from the validation of both methods are summarized in the table below, offering a clear comparison of their performance against key validation parameters [1].

| Validation Parameter | UV-Spectrophotometric Method | RP-HPLC Method |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range | 5 - 30 µg/ml | 5 - 50 µg/ml |

| Regression Coefficient (r²) | > 0.999 | > 0.999 |

| Precision (% R.S.D.) | < 1.50% | < 1.50% (more precise than UV) |

| Accuracy (% Mean Recovery) | 99.63 - 100.45% | 99.71 - 100.25% |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) & Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Determined via calibration curve | Determined via calibration curve |

| Remarks | Reliable, simple, fast, economical | Highly precise, specific, and reliable |

The study concluded that while both methods were successful for quality control, the HPLC method demonstrated higher precision and a broader linear range, making it more suitable for specific quantitative applications. The UV method, however, was noted as a simple, fast, and economical alternative [1]. This variance in performance highlights the importance of selecting the analytical technique based on the intended use of the method, a core principle of all validation guidelines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The execution of validated methods requires high-quality materials and reagents. The following table details key items essential for analytical method development and validation, particularly for chromatographic and spectrophotometric techniques.

| Item / Reagent Solution | Critical Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Reference Standards | High-purity analyte used to prepare calibration standards; essential for establishing method accuracy, linearity, and for system suitability tests [1]. |

| HPLC/GC Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile) used for mobile phase and sample preparation; minimize background noise and prevent system damage [1]. |

| Chromatographic Columns | The stationary phase (e.g., C18) where chemical separation occurs; column selection is a primary variable affecting resolution, selectivity, and peak shape [1] [12]. |

| Buffer Salts | Used to control the pH of the mobile phase; critical for achieving consistent retention times and separation, especially for ionizable compounds [1] [12]. |

| Filters (Membrane/Syringe) | Used to remove particulate matter from samples and mobile phases; prevents column blockage and ensures data accuracy, particularly in dissolution testing [15]. |

The guidelines provided by ICH, USP, and FDA form a cohesive yet multi-faceted foundation for analytical method validation. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides the universal scientific and technical framework. The USP translates this framework into actionable, test-specific standards for the United States, formally categorizing methods and their requirements. The FDA reinforces these principles with a strong emphasis on risk management and product quality throughout the method's lifecycle.

The experimental case study on repaglinide underscores that while different analytical techniques (like UV and HPLC) can be successfully validated per these guidelines, their performance characteristics will vary. Chromatographic methods generally offer superior precision and specificity, while spectrophotometric methods can provide a simpler, more economical solution where fit-for-purpose. Therefore, the choice of technique and the application of validation parameters must always be guided by the method's intended use, in strict adherence to the relevant regulatory foundations.

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, spectrophotometric and chromatographic techniques are foundational for drug quantification and quality control. Despite being used for similar purposes, these methods possess distinct analytical characteristics that lead to inherent variances in their results. Understanding the sources of these discrepancies is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the appropriate method, interpret data accurately, and ensure reliable outcomes. This guide objectively compares the performance of these techniques, supported by experimental data, to elucidate the fundamental reasons behind their variances, framed within the broader context of analytical results research.

Core Principles and Mechanisms of Variance

The fundamental differences in how spectrophotometry and chromatography separate and detect analytes are the primary source of inherent variance.

Spectrophotometry operates on the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species [16]. It measures the interaction of electromagnetic radiation (typically UV or Visible light) with molecules in a sample, providing a composite signal if multiple absorbing compounds are present.

Chromatography, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), separates the components of a mixture based on their differential partitioning between a mobile phase and a stationary phase [17]. Each component elutes at a different time, and a detector (often UV-based) then quantifies the isolated analytes.

The key distinction lies in specificity: chromatography physically separates analytes before detection, while spectrophotometry measures the cumulative absorbance of the entire sample without separation. This core mechanistic difference is the origin of most variances in their performance, especially when analyzing complex mixtures like pharmaceutical formulations containing excipients or degradation products.

Comparative Experimental Data: A Case Study

A direct comparison study on the antidiabetic drug repaglinide effectively illustrates the performance variances between the two techniques. The methods were developed and validated according to International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, providing a standardized framework for comparison [1].

Table 1: Validation Parameters for Spectrophotometric and HPLC Methods for Repaglinide Analysis

| Validation Parameter | UV Spectrophotometric Method | RP-HPLC Method |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Wavelength | 241 nm | 241 nm |

| Linearity Range | 5–30 μg/mL | 5–50 μg/mL |

| Regression Coefficient (r²) | > 0.999 | > 0.999 |

| Precision (% R.S.D.) | < 1.50 | Highly precise (better than UV) |

| Mean Recovery | 99.63 – 100.45% | 99.71 – 100.25% |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Determined from calibration curve | Determined from calibration curve |

This data shows that while both methods demonstrated excellent linearity and accuracy in the recovery experiments, the HPLC method exhibited superior precision and a wider linear range. The broader linear range in HPLC is often attributable to its separation step, which minimizes detector saturation or non-specific interactions that can affect spectrophotometric signals at higher concentrations [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To understand how the data in the case study was generated, the following outlines the key methodological steps for each technique.

UV Spectrophotometric Protocol for Repaglinide

- Instrumentation: A double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer with 1.0 cm quartz cells was used [1].

- Solvent and Wavelength: Methanol was used as the solvent. The wavelength of 241 nm was selected based on the maximum absorption of repaglinide [1].

- Standard Solution Preparation: A stock solution of 1000 μg/mL of repaglinide was prepared in methanol. Appropriate dilutions were made to prepare standard solutions in the concentration range of 5–30 μg/mL [1].

- Sample Preparation: Twenty tablets were weighed and powdered. A portion equivalent to 10 mg of repaglinide was dissolved in methanol, sonicated for 15 minutes, and diluted to volume. The solution was filtered, and the filtrate was diluted to a concentration within the linearity range [1].

- Measurement: The absorbance of the standard and sample solutions was measured against methanol as a blank. The concentration was determined from the calibration curve [1].

RP-HPLC Protocol for Repaglinide

- Instrumentation: An HPLC system with a UV detector and a C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size) was used [1].

- Mobile Phase: A mixture of methanol and water in a 80:20 ratio was used. The pH was adjusted to 3.5 with orthophosphoric acid. The flow rate was maintained at 1.0 mL/min [1].

- Detection: The eluent was monitored at 241 nm [1].

- Standard Solution Preparation: The stock solution was diluted with the mobile phase to reach a concentration range of 5–50 μg/mL [1].

- Sample Preparation: The tablet filtrate was diluted with the mobile phase to a concentration within the linearity range [1].

- Injection and Analysis: 20 μL of the standard or sample solution was injected into the chromatograph. The peak area was used for quantification [1].

The experimental protocols and data highlight several specific sources of variance between the two techniques.

Specificity and Interference

This is the most significant source of variance. Spectrophotometry lacks a separation step, making the signal vulnerable to interference from other UV-absorbing substances, such as formulation excipients or degradation products [1] [18]. In contrast, HPLC's core strength is its ability to separate the analyte from potential interferents, resulting in a more specific and reliable measurement [1] [19].

Precision

As seen in Table 1, HPLC consistently demonstrates higher precision. Spectrophotometric measurements can be influenced by factors like cell positioning, path length variations, and stray light, leading to higher relative standard deviations [20]. HPLC's automated injection and detection under controlled flow conditions contribute to its superior reproducibility [19].

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection

While not directly shown in the repaglinide data, chromatographic methods are often more sensitive. This is because they measure the analyte in an isolated form, free from the background "noise" of the sample matrix, which can obscure the signal in spectrophotometry, particularly at low concentrations [8].

Spectrophotometers are susceptible to errors related to wavelength accuracy, bandwidth, and stray light, which can significantly impact absorbance measurements if not properly calibrated [20]. HPLC systems, while generally robust, introduce variance sources related to the chromatographic process itself, including pump flow rate stability, column temperature fluctuations, and column-to-column performance variability [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials used in the development and application of these analytical methods, based on the cited experimental work.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Methanol / Acetonitrile | Common organic solvents used to dissolve analytes and as components of the mobile phase in HPLC. | Used as solvent for repaglinide in UV analysis and in mobile phase for HPLC [1]. |

| C18 Column | A reversed-phase chromatographic column; the most common stationary phase for separating non-polar to moderately polar compounds. | Agilent TC-C18 column used for separation of repaglinide [1]. |

| Buffer Salts / pH Adjusters | Used to control the pH of the mobile phase, which critically affects the separation efficiency and peak shape in HPLC. | Orthophosphoric acid used to adjust mobile phase pH to 3.5 for repaglinide analysis [1]. |

| Standard Reference Compound | A highly pure form of the analyte used to prepare calibration standards, essential for accurate quantification. | Repaglinide reference standard obtained for method development and validation [1]. |

| Picric Acid / Bromophenol Blue | Reagents used in derivatization or complex formation to enable or enhance spectrophotometric detection of certain drugs. | Used for spectrophotometric determination of drugs like bisoprolol and repaglinide via complex formation [18]. |

The inherent variances between spectrophotometric and chromatographic techniques are not a matter of one being universally superior to the other, but rather a reflection of their fundamentally different operational principles. Spectrophotometry offers simplicity, speed, and cost-effectiveness but is more susceptible to interference from complex matrices. Chromatography provides high specificity, superior precision, and robust quantification in the presence of interferents, at the cost of greater operational complexity and time per analysis.

The choice between techniques should be guided by the analytical requirements of the specific application. For rapid, routine analysis of pure substances, spectrophotometry may be sufficient and more efficient. However, for method development, stability-indicating assays, or analysis of complex mixtures like pharmaceutical formulations and biological samples, chromatography is the unequivocal choice due to its superior ability to isolate and quantify the analyte of interest, thereby minimizing variance and ensuring result reliability.

The selection of an appropriate analytical technique is a critical step in method development, directly influencing the accuracy, reliability, and efficiency of chemical analysis. For researchers and drug development professionals, the fundamental properties of target analytes—specifically their volatility, polarity, and presence of chromophores—serve as primary determinants in choosing between spectrophotometric and chromatographic methods [21] [22]. Within chromatography, these properties further dictate the choice between gas (GC) and liquid (HPLC) techniques, as well as the selection of specific stationary phases and detection systems [21] [23] [24].

Understanding these relationships is essential within broader research on variance between spectrophotometric and chromatographic results. This guide objectively compares technique performance based on analyte properties, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform analytical decision-making.

Core Analyte Properties and Technical Implications

Volatility and Thermal Stability

Volatility determines whether an analyte can be efficiently vaporized without decomposition, making it the principal factor in GC applicability [21].

- GC-Suitable Analytes: Volatile and thermally stable compounds (e.g., hydrocarbons, solvents, aroma compounds) are ideal for GC, where separation occurs in a heated column using an inert gas mobile phase [21].

- HPLC for Non-Volatile/Unstable Analytes: Non-volatile, thermally unstable, or high-molecular-weight compounds (e.g., biologics, pharmaceuticals, sugars) require HPLC, which uses a liquid mobile phase at ambient or low temperatures [21] [23].

Polarity

Polarity influences analyte interaction with stationary phases in both GC and HPLC [21] [25].

- GC Stationary Phase Selection: In GC, the "like dissolves like" principle generally applies. Polar stationary phases (e.g., polyethylene glycol) retain polar analytes through hydrogen bonding and dipole interactions, while non-polar phases (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane) retain non-polar analytes via dispersive forces [25]. However, McReynolds constants and polarity scales should be used cautiously, as high polarity numbers do not always correlate with greater retention or selectivity [25].

- HPLC Mode Selection: Analyte polarity dictates the HPLC mode:

- Reversed-Phase (RP-HPLC): Uses a non-polar stationary phase (e.g., C18) and polar mobile phase. It struggles with highly polar analytes, which may elute near the void volume [23].

- Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC): Employs a polar stationary phase and acetonitrile-rich mobile phase to retain and separate highly polar compounds [23] [26].

- Mixed-Mode Chromatography: Combines reversed-phase and ion-exchange mechanisms to simultaneously retain polar and non-polar compounds [23] [27].

- Aqueous Normal Phase (ANP) Chromatography: A specific type of separation on silicon-hydride-based stationary phases that can retain both polar and non-polar compounds in a single isocratic run, with retention for polar compounds increasing with organic solvent content [27].

Chromophores

Chromophores are light-absorbing functional groups in molecules (e.g., carbonyls, nitro groups, conjugated systems) that enable detection by UV-Vis spectrophotometry and HPLC with UV-Vis detectors [22] [24].

- Compounds with Strong Chromophores can be directly analyzed using UV-Vis spectrophotometry or HPLC-UV [22].

- Compounds with Weak or No Chromophores (e.g., sugars, alcohols, many pharmaceuticals) present detection challenges for UV-based methods and require alternative techniques [24]. Solutions include:

- Derivatization: Chemically modifying analytes to attach chromophores or fluorophores [28] [22].

- Alternative Detectors: Using mass spectrometry (MS), charged aerosol detection (CAD), evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD), or refractive index detection (RID) in HPLC [24].

- Specialized HPLC Methods: Employing techniques like HILIC-MS for polar compounds without strong chromophores [29].

The following table summarizes the primary technique selection guidance based on these core properties.

Table 1: Analytical Technique Selection Based on Core Analyte Properties

| Analyte Property | Recommended Technique | Key Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile & Thermally Stable | Gas Chromatography (GC) [21] | Petrochemicals, aroma compounds, environmental VOCs [21] | Fast analysis, high resolution, requires volatility [21] |

| Non-Volatile or Thermally Unstable | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [21] | Pharmaceuticals, biologics, sugars [21] [23] | Broad applicability, uses liquid mobile phase [21] |

| Highly Polar | HILIC or Mixed-Mode HPLC [23] | Sugars, amino acids, metabolites, polar pesticides [23] [29] | Uses polar stationary phase and organic-rich mobile phase [23] |

| Contains Strong Chromophore | UV-Vis Spectrophotometry or HPLC-UV [22] [24] | Drug assays in formulations, dissolution testing [22] | Simple, cost-effective; limited to absorbing compounds [22] |

| Lacks Chromophore | HPLC with Alternative Detection (MS, CAD, ELSD, RID) [24] | Impurity profiling, weak-chromophore drug analysis [24] | May require derivatization or specialized detectors [28] [24] |

Comparative Experimental Data and Method Performance

Experimental studies directly comparing techniques for specific analyte classes provide critical performance data. The following table summarizes key findings from validation research, illustrating the precision and accuracy of different methodological approaches.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Method Performance

| Analyte Class | Methodology | Accuracy (%) | Precision (% RSD) | Linear Range | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs) in Fermentation | Modified Spectrophotometric Method [30] | 94.68 – 106.50 | 2.35 – 9.26 | 250 – 5000 mg/L for C2-C6 VFAs | Offers rapid, inexpensive analysis suitable for routine monitoring [30] |

| Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs) in Fermentation | Gas Chromatography (GC) [30] | 94.42 – 99.13 | 0.17 – 1.93 | Not Specified | Higher precision and robust accuracy; requires skilled operator and higher cost [30] |

| Polar Pesticides in Chicken Eggs | UPLC-MS with Hypercarb Column [29] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Effective for polar pesticides; column choice is critical for retention and peak shape in complex matrices [29] |

| Polar Pesticides in Chicken Eggs | UPLC-MS with Raptor Polar X Column [29] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Suitable for polar pesticide analysis; performance varies by stationary phase [29] |

| Polar Pesticides in Chicken Eggs | UPLC-MS with Anionic Polar Pesticide Column [29] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Designed for high-polarity pesticides; provides necessary retention and selectivity [29] |

| Drugs with Weak Chromophores | HPLC with UV/Vis Detection [24] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Limited for compounds lacking chromophores [24] |

| Drugs with Weak Chromophores | HPLC with CAD/ELSD/RID [24] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Universal detectors suitable for non-UV-absorbing compounds [24] |

| Drugs with Weak Chromophores | HPLC-MS [24] | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Provides high sensitivity and selectivity; higher cost and operational complexity [24] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Spectrophotometric Protocol for Volatile Fatty Acid Determination

This protocol, adapted from a study on fermentation samples, details a spectrophotometric method for quantifying high-range VFA concentrations [30].

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Spectrophotometric VFA Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethylene Glycol | Reaction solvent for ester formation | Serves as both solvent and reactant [30] |

| Hydroxylamine Hydrochloride (NH₂OH·HCl) | Forms hydroxamic acids with esters | Critical for color complex development [30] |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Provides alkaline catalysis | Catalyzes ester formation [30] |

| Ferric Chloride (FeCl₃) | Forms colored complex with hydroxamates | Produces measurable chromophore [30] |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Acidifies reaction mixture | Stops reaction and develops color [30] |

| VFA Standards | Calibration (e.g., Acetic, Propionic, Butyric acids) | ≥99% purity for accurate standard curves [30] |

4.1.2 Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Centrifuge fermentation samples at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes to remove particulate matter [30].

- Ester Formation: Mix 1.0 mL of sample or standard with 2.0 mL of ethylene glycol and 0.5 mL of 3M H₂SO₄. Heat the mixture at 100°C for 60 minutes to form VFA esters, then cool to room temperature [30].

- Hydroxamic Acid Formation: Add 1.0 mL of 2M NH₂OH·HCl (prepared in 3.5M NaOH) to the cooled mixture. Allow the reaction to proceed for 10 minutes at room temperature [30].

- Color Development: Add 1.0 mL of 2M HCl and 1.0 mL of 0.37M FeCl₃ solution. Mix thoroughly to form the ferric-hydroxamate complex [30].

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance of the solution at 505 nm against a reagent blank [30].

- Quantification: Calculate VFA concentrations using a calibration curve prepared from standard solutions of known concentrations (e.g., 250–5000 mg/L) [30].

Chromatographic Protocol for Polar Compound Analysis

This protocol outlines HILIC-based separation for polar analytes, such as pesticides or metabolites, using conditions derived from column comparison studies [29] [26].

4.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for HILIC Analysis of Polar Compounds

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HILIC Column | Stationary phase for polar analyte retention | Options: Zwitterionic, amide, or amino-functionalized silica [26] |

| Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Organic mobile phase component | High purity to minimize background noise [28] [23] |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | Aqueous mobile phase component | Provides ionic strength; typical concentration 5-20 mM, pH 4.7-5.8 [26] |

| Polar Analytic Standards | Calibration and identification | E.g., glyphosate, amino acids, sugars [29] [26] |

4.2.2 Procedure

- Column Selection and Equilibration: Select an appropriate HILIC column (e.g., zwitterionic or amide). Equilibrate the column with initial mobile phase (typically >80% acetonitrile with 5-20 mM ammonium acetate buffer) for sufficient time to ensure reproducible retention (may require more time than reversed-phase methods) [23] [26].

- Sample Preparation: For complex matrices like chicken eggs, perform extraction and purification steps (e.g., freeze-out, centrifugation, filtration). Dissolve the sample in a diluent matching the initial mobile phase composition (e.g., 75/25 acetonitrile-methanol mix) to maintain peak shape [23] [29].

- Chromatographic Separation:

- Use a UPLC or HPLC system coupled with a mass spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF) or other suitable detector [29].

- Employ a mobile phase of acetonitrile and ammonium acetate buffer (e.g., 5-20 mM, pH 5.8).

- Apply a gradient elution, typically starting with high organic content (e.g., 90% acetonitrile) and decreasing to increase elution strength for more polar analytes [29] [26].

- Maintain column temperature at 25-40°C for stability [29].

- Detection and Quantification: Use mass spectrometry in appropriate ionization mode for detection. Identify analytes by retention time and mass-to-charge ratio. Quantify using external calibration curves from standard solutions [29].

Analytical Technique Decision Workflow

The following diagram maps the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate analytical technique based on analyte properties, integrating the principles discussed throughout this guide.

Diagram 1: Analytical Technique Decision Workflow

The selection between spectrophotometric and chromatographic techniques, and the specific variant within each category, is fundamentally guided by the volatility, polarity, and chromophore presence of the target analytes. GC remains the superior choice for volatile, thermally stable compounds, while HPLC and its specialized modes (e.g., HILIC, Mixed-Mode) are indispensable for non-volatile and polar substances. Spectrophotometry offers a straightforward and cost-effective solution for compounds with strong chromophores, whereas analytes lacking chromophores necessitate advanced HPLC detectors or derivatization.

Experimental data demonstrates that while chromatographic methods often provide superior precision, well-developed spectrophotometric techniques can yield highly accurate and practically useful results, particularly for routine monitoring. The observed variance between these techniques underscores the importance of aligning method selection with analyte characteristics and analytical objectives. For researchers in drug development and related fields, a rigorous assessment of these core analyte properties provides a reliable framework for selecting the optimal analytical technique, thereby ensuring data quality and supporting robust scientific conclusions.

From Theory to Bench: Developing and Applying UV and HPLC Methods for Drug Analysis

Step-by-Step Development of a UV-Spectrophotometric Method for API Assay

In the pharmaceutical industry, the accurate quantification of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is a cornerstone of quality control and drug development. Analytical techniques range from simple, cost-effective methods to complex, high-tech instrumentation. UV-Spectrophotometry stands as a fundamental tool in this landscape, prized for its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and rapid analysis time. This guide provides a systematic, step-by-step framework for developing and validating a UV-spectrophotometric method for API assay. Furthermore, it objectively compares this technique with the more sophisticated chromatographic methods, situating the discussion within a broader thesis on analyzing variance between spectrophotometric and chromatographic results. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of each method is crucial for method selection, results interpretation, and ensuring the reliability of analytical data in drug development.

Performance Comparison: Spectrophotometry vs. Chromatography

The choice between spectrophotometric and chromatographic methods often involves a trade-off between simplicity and selectivity. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of the two techniques based on recent research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of UV-Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Methods for API Assay

| Analytical Feature | UV-Spectrophotometry | Chromatography (e.g., UFLC-DAD, HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Operational Simplicity | High; simplified procedures and operation [31] | Lower; requires complex instrumentation and expertise [31] |

| Cost & Solvent Consumption | Lower cost; reduced solvent consumption [31] | Higher cost and solvent usage [32] |

| Analysis Speed | High; rapid analysis [31] | Shorter analysis time than HPLC, but generally slower than UV [31] |

| Selectivity & Specificity | Can struggle with spectral overlaps in mixtures [31] | High selectivity; can separate complex mixtures effectively [31] |

| Handling Complex Mixtures | Requires advanced techniques (e.g., chemometrics, derivative spectroscopy) for resolution [32] [2] | Inherently designed for multi-component analysis [31] |

| Sample Concentration Limits | Limited dynamic range; struggles with very high concentrations [31] | Wider dynamic range; suitable for a broad concentration spectrum [31] |

| Greenness (AGREE Metric) | Generally higher greenness score [31] | Lower greenness score due to higher solvent consumption [31] |

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | Glibenclamide: 98.47-101.21% [33]; Citicoline: 98.41% [34] | OFL/TZ in Hydrotropic Solution: ~100.4% [32] |

| Precision (%RSD) | Typically <2% [33] [34] | Comparable high precision [32] |

Statistical analysis of variance (ANOVA) is a key tool for comparing results from these different methods. Studies have shown that when comparing the determined concentrations of an API like metoprolol tartrate from commercial tablets, no significant difference was found between the results obtained from validated UV-spectrophotometric and UFLC-DAD methods at a 95% confidence level [31]. This indicates that for many routine analyses, a well-developed spectrophotometric method can provide results statistically equivalent to those from more complex chromatographic systems.

Step-by-Step Method Development Protocol

Step 1: Standard Stock Solution Preparation

Accurately weigh approximately 10 mg of the API standard. Transfer it to a 100 mL volumetric flask and dissolve in a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol, distilled water, or 0.1N HCl). Make up to volume with the solvent to obtain a primary stock solution with a concentration of about 100 µg/mL [33] [35] [36]. For APIs with poor solubility, an initial dissolution in a small volume of a stronger solvent (e.g., methanol) followed by dilution with the primary solvent is effective [33].

Step 2: Determination of Wavelength of Maximum Absorbance (λmax)

Dilute an aliquot of the standard stock solution to a concentration within the expected linear range (e.g., 5-10 µg/mL). Scan the diluted solution over the UV range (e.g., 200-400 nm) against a solvent blank. The wavelength at which maximum absorbance occurs is identified as the λmax for the analysis. Examples from research include:

- Glibenclamide: 324 nm in distilled water [33]

- Rosuvastatin Calcium: 240 nm in phosphate buffer [35]

- Citicoline: 280 nm in 0.1N HCl [34]

- Atovaquone: 251 nm in methanol [36]

Step 3: Construction of the Calibration Curve

Prepare a series of standard solutions from the stock solution to cover a defined concentration range. For instance:

- Prazosin: 5-80 µg/mL [37]

- Rosuvastatin Calcium: 2-20 µg/mL [35]

- Glibenclamide: 2-10 µg/mL [33]

- Citicoline: 10-80 µg/mL [34] Measure the absorbance of each standard solution at the determined λmax and plot absorbance versus concentration. The plot should yield a linear relationship conforming to Beer-Lambert's law, with a high correlation coefficient (R²) typically >0.999 [33] [35] [34].

Step 4: Analysis of the Dosage Form

Weigh and finely powder not less than 20 tablets. Accurately weigh a portion of the powder equivalent to the API weight in a single tablet. Dissolve it in the chosen solvent, dilute to an appropriate volume, and filter if necessary. Further dilute the solution to bring its concentration within the linear range of the calibration curve. Measure the absorbance and use the regression equation from the calibration curve to calculate the API concentration in the sample [35] [36].

Figure 1: UV-Spectrophotometric Method Development and Validation Workflow

Advanced Spectrophotometric Techniques for Complex Assays

For simple formulations, the basic protocol suffices. However, quantifying an API in a multi-component dosage form or in the presence of interfering impurities presents a challenge due to spectral overlap. Advanced techniques have been developed to resolve these issues.

- Derivative and Ratio Spectrophotometry: These methods enhance selectivity by resolving overlapping spectra. For instance, the first derivative of ratio spectra was used to determine Lidocaine in a ternary mixture with Oxytetracycline and a carcinogenic impurity, effectively resolving the analyte's signal from interferents [2].

- Chemometrics-Assisted Spectrophotometry: Multivariate calibration methods like Principal Component Regression (PCR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) are powerful tools. These computational techniques can deconvolute severe spectral overlaps without the need for physical separation. A study on the antimicrobial combination of Ofloxacin and Tinidazole demonstrated that PLS and PCR models yielded mean recoveries of 102.3-102.6%, showing excellent agreement with chromatographic methods when validated with ANOVA [32].

Method Validation as per ICH Guidelines

A method is only useful if it is validated. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guideline Q2(R1) defines the key parameters to be assessed [33] [35].

Table 2: Key Validation Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria

| Validation Parameter | Description & Protocol | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity & Range | Measure absorbance of a series of standard solutions. Plot concentration vs. absorbance and perform linear regression. | Correlation coefficient (R²) ≥ 0.999 [33] [34] |

| Accuracy (Recovery) | Spike a pre-analyzed sample with known amounts of standard API (e.g., at 80%, 100%, 120% levels). Calculate % recovery. | Recovery between 98-102% [33] [34] |

| Precision | Repeatability (Intra-day): Analyze multiple replicates (n=3-6) at different concentrations within the same day.Intermediate Precision (Inter-day): Perform analysis on different days or by different analysts. | Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) < 2% [33] [35] |

| LOD & LOQ | LOD = 3.3 × σ/S; LOQ = 10 × σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve. | Glibenclamide: LOD=0.35 µg/mL, LOQ=1.06 µg/mL [33] |

| Specificity | Demonstrate that the absorbance measured is due to the API alone and not from excipients, impurities, or degradation products. | No interference from blank or other components at the λmax [2] [31] |

| Robustness | Deliberately introduce small changes in method parameters (e.g., wavelength ±1 nm, pH of buffer) and observe the impact on results. | Method should remain unaffected by small variations (%RSD remains <2%) [33] |

Figure 2: Basic Components of a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for UV-Spectrophotometric API Assay

| Item | Function & Importance | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity API Standard | Serves as the reference material for calibration; purity is critical for accuracy. | Metoprolol Tartrate (≥98%, Sigma-Aldrich) [31] |

| Appropriate Solvent | Dissolves the API and forms a transparent solution for analysis; should not absorb at the λmax. | Methanol for Atovaquone [36]; Distilled water for Glibenclamide [33]; 0.1N HCl for Citicoline [34] |

| Buffer Salts | Maintains a constant pH, which is crucial for APIs whose absorbance is pH-dependent. | Phosphate buffers (pH 6.8 & 7.4) for Rosuvastatin Calcium [35] |

| Volumetric Glassware | Ensures precise and accurate dilution and volume measurements (Class A recommended). | Used in all standard and sample preparation steps [35] [36] |

| UV-Transparent Cuvettes | Holds the sample solution in the light path; must be transparent in the UV range. | Quartz cells with 1 cm path length are standard [35] [2] |

The development of a UV-spectrophotometric method for API assay is a structured process involving solution preparation, wavelength determination, calibration, and rigorous validation. While its limitations in analyzing complex mixtures are evident, its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness make it an invaluable technique for many routine analytical applications. The emergence of advanced chemometric models has further expanded its capability to handle more challenging analyses, often providing results that show no significant variance from those obtained by chromatographic methods. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this technique provides a powerful, reliable, and green tool for quality control and in-process testing, ensuring that therapeutic products meet their stringent quality specifications.

Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) stands as the most widely used chromatographic technique in pharmaceutical analysis due to its exceptional versatility, reproducibility, and compatibility with mass spectrometry [38] [39]. The development of robust RP-HPLC methods requires systematic optimization of three critical components: the chromatographic column, mobile phase composition, and detection parameters. When framed within research investigating variances between spectrophotometric and chromatographic results, the superior selectivity of HPLC becomes particularly evident. While spectrophotometric methods provide rapid screening, they often lack the specificity to resolve complex mixtures, leading to potential inaccuracies in quantification that are effectively addressed by properly developed chromatographic methods [40] [32]. This guide examines the key factors in RP-HPLC method development, supported by experimental data and comparative analysis of approaches.

Critical Component I: Column Selection Strategies

Stationary Phase Chemistry and Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate HPLC column is fundamental to successful method development, as the stationary phase directly governs selectivity, retention, and resolution [41]. Reverse-phase columns dominate approximately 70-80% of pharmaceutical applications, with C18 (ODS) being the most widely used stationary phase due to its extensive hydrophobicity and broad applicability [38] [39].

Table 1: Common Reverse-Phase HPLC Column Types and Properties

| Stationary Phase | Alkyl Chain Length | Retention Characteristics | Best Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C18 (ODS) | 18 carbon | Strongest hydrophobic retention | Wide range of small molecules, pharmaceuticals | Default choice; may show phase collapse with high aqueous mobile phases |

| C8 | 8 carbon | Moderate retention | Peptides, proteins | Shorter chain length provides less retention than C18 |

| Phenyl | Phenyl ring | π-π interactions with aromatic compounds | Compounds with aromatic rings | Offers different selectivity for positional isomers |

| C4 | 4 carbon | Weak retention | Proteins, peptides | Suitable for large biomolecules |

| CN (Cyano) | Cyano group | Dual-mode (RP and NP) | Moderate polarity compounds | Useful for scouting methods |

The fundamental parameter for column selection is analyte polarity. RP-HPLC is ideal for non-polar to moderately polar compounds, while normal-phase chromatography (NPC) may be preferable for highly polar substances [38]. The chemical structure, functional groups, and molecular size of analytes should guide stationary phase selection, with C18 serving as the default starting point for method development.

Column Physical Parameters and Performance Characteristics

Beyond stationary phase chemistry, physical parameters significantly impact method performance. Particle size directly affects efficiency and backpressure, with modern trends favoring smaller particles for improved resolution [39].

Table 2: Column Physical Parameters and Their Method Development Implications

| Parameter | Typical Options | Impact on Separation | Instrument Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | 5 µm (conventional), 3-3.5 µm (improved efficiency), 1.7-2 µm (UHPLC) | Smaller particles increase efficiency (theoretical plates) but raise backpressure | UHPLC particles require high-pressure capable systems |

| Pore Size | 120Å (small molecules), 300Å (proteins, peptides) | Must accommodate analyte molecular size | Large biomolecules require wider pores to access stationary phase |

| Column Dimensions | 150×4.6 mm (standard), 50-100×2.1 mm (fast analysis, UHPLC) | Shorter columns reduce runtime; narrower diameters increase sensitivity | Smaller diameters reduce solvent consumption but may require flow splitting |

The selection process should also consider column characterization parameters, including theoretical plate number (efficiency), asymmetry factor (peak shape), and reproducibility of retention time [41]. Modern advancements include extended pH-stable hybrid silica phases (pH 1-12), core-shell technology for high efficiency at lower back pressures, and polar-embedded phases for improved peak shape of basic drugs [39].

Critical Component II: Mobile Phase Optimization

Composition and Modifier Effects

Mobile phase optimization represents perhaps the most powerful approach for manipulating selectivity and retention in RP-HPLC. The typical RP-HPLC mobile phase consists of water (aqueous component) mixed with a water-miscible organic solvent (organic modifier) [38]. The most common organic modifiers are acetonitrile and methanol, with acetonitrile generally preferred for its low viscosity and UV transparency.

Experimental studies demonstrate how mobile phase composition directly impacts critical method parameters. In the determination of repaglinide, researchers achieved optimal separation using a mobile phase of methanol and water (80:20 v/v, pH adjusted to 3.5 with orthophosphoric acid) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min [40]. Similarly, for remogliflozin etabonate, method development trials revealed that acetonitrile:water (75:25 v/v) provided significantly better peak symmetry and shorter retention time compared to methanol-based systems [42].

The pH of the mobile phase profoundly impacts the ionization state of ionizable analytes, thereby influencing retention and peak shape. For compounds containing acidic or basic functional groups, controlling mobile phase pH is essential for achieving acceptable chromatography. Buffer systems such as phosphate, acetate, or ammonium salts are typically employed to maintain consistent pH, with concentrations commonly ranging from 10-50 mM [43] [44].

Systematic Optimization Using Design of Experiments

Modern method development increasingly employs Quality by Design (QbD) principles and Design of Experiments (DoE) for systematic optimization. A study on rosuvastatin and bempedoic acid utilized a Plackett-Burman design to screen seven method parameters, identifying % aqueous content, buffer pH, and flow rate as critical method parameters [44]. Subsequent optimization using a Box-Behnken design established the final conditions: 15 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.0) and acetonitrile (40:60% v/v) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min [44].

This AQbD approach represents a significant advancement over traditional one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) optimization, as it efficiently identifies interactions between variables and establishes a design space where the method remains robust despite minor variations [44]. The greenness of the developed method was evaluated using AGREE software, yielding a score of 0.72, indicating compliance with Green Analytical Chemistry principles [44].

Critical Component III: Detection Strategy Selection

Wavelength Selection and Method Specificity

Proper detection wavelength selection is crucial for achieving optimal sensitivity and specificity in RP-HPLC methods. The process should begin with analyzing standard solutions using a photodiode array (PDA) or diode array detector (DAD) in full scan mode (typically 200-400 nm) to identify the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) for each analyte [45].

Research on eptifibatide acetate illustrates this principle well. While the compound showed maximum absorbance at 219 nm, the wavelength of 275 nm was selected for the final method because it provided a clearer baseline and prevented interference from trifluoroacetic acid in the mobile phase [43]. Similarly, in the simultaneous estimation of metformin and sesamol, researchers selected 230 nm as a common isosbestic point for both compounds, enabling simultaneous detection despite their individual λmax values being 266 nm and 307 nm, respectively [46].

When developing methods for multiple components, the use of a scanning DAD detector is strongly recommended over single-wavelength detectors, as it enables peak purity assessment and identification of co-eluting impurities that might be missed at a single wavelength [45]. This capability is particularly valuable when investigating discrepancies between spectrophotometric and chromatographic results, as it provides spectral confirmation of peak identity and purity.

Advanced Detection Strategies

For methods requiring higher sensitivity or specificity, especially in complex matrices, several advanced detection strategies are available. Many modern HPLC methods couple UV detection with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for definitive compound identification, though this approach involves higher instrumentation costs [39]. When developing stability-indicating methods, the use of DAD detectors to obtain spectral data across the entire elution profile enables peak homogeneity assessment and detection of potential degradants that may co-elute with the main peak [44].

The selection of detection parameters should also consider the analytical goal—quantitative assays typically prioritize sensitivity, while purity methods require comprehensive profiling across multiple wavelengths to detect potential impurities with different chromophores [45].

Comparative Experimental Data and Case Studies

Method Performance Across Drug Classes

Experimental data from multiple studies demonstrates how robust RP-HPLC methods perform across different pharmaceutical compounds. The following table summarizes key validation parameters from published methods:

Table 3: Comparative RP-HPLC Method Performance Across Drug Classes

| Analyte | Column | Mobile Phase | Linearity (r²) | Retention Time (min) | LOD/LOQ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eptifibatide acetate | C18 (150×4.6 mm, 5µm) | 0.1% TFA in ACN:Water (32:68) | 0.997 | <3.0 | 0.15 mg/mL (LOD) | [43] |

| Repaglinide | TC-C18 (250×4.6 mm, 5µm) | MeOH:Water (80:20, pH 3.5) | >0.999 | Not specified | 5-50 µg/mL (range) | [40] |

| Remogliflozin etabonate | Inertsil ODS-3V (150×4.6 mm, 5µm) | ACN:Water (75:25) | 0.999 | 2.55 | 0.22/0.68 µg/mL | [42] |

| Rosuvastatin & Bempedoic acid | Spursil C18 (150×4.6 mm, 5µm) | Ammonium acetate (pH 6):ACN (40:60) | >0.999 | 2.474/3.396 | Not specified | [44] |

| Metformin & Sesamol | Purospher STAR RP-18 (250×4.6 mm, 5µm) | ACN:Water (30:70) | 0.9947/0.9908 | Not specified | 0.89/2.71 (Met), 1.27/3.86 (Ses) µg/mL | [46] |

These case studies reveal several important patterns. First, C18 columns serve as the default choice across diverse drug molecules. Second, acetonitrile generally provides better peak symmetry compared to methanol, though both organic modifiers are widely used. Third, the isocratic elution mode is sufficient for many pharmaceutical applications, particularly for quality control of single active ingredients.

Resolution of Spectrophotometric-Chromatographic Discrepancies