A Complete Guide to Polyacrylamide Gel Preparation for Protein Electrophoresis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on preparing polyacrylamide gels for protein electrophoresis.

A Complete Guide to Polyacrylamide Gel Preparation for Protein Electrophoresis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on preparing polyacrylamide gels for protein electrophoresis. It covers the foundational principles of SDS-PAGE and native PAGE, delivers a detailed step-by-step methodological protocol for gel casting and sample preparation, offers extensive troubleshooting for common issues like poor band separation and sample leakage, and validates the methods through comparison with advanced techniques like Blue-Native PAGE. The content is designed to equip practitioners with the knowledge to achieve reproducible, high-quality results in protein analysis for biomedical research.

Understanding Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis: Principles and Core Concepts

What is Gel Electrophoresis and Why is it Indispensable for Protein Analysis?

Gel electrophoresis is a fundamental analytical technique used in molecular biology and biochemistry to separate macromolecules—including proteins, DNA, and RNA—based on their size, charge, and shape. The general principle involves applying an electric current to a gel matrix, causing charged particles to migrate towards the electrode with the opposite charge. The gel matrix acts as a molecular sieve, allowing smaller molecules to move faster and farther than larger ones, resulting in distinct bands that can be visualized and analyzed [1].

The technique's indispensability in protein analysis stems from its high resolution, sensitivity, and versatility. It enables researchers to separate complex protein mixtures, determine molecular weights, identify protein isoforms, analyze protein-protein interactions, and assess sample purity. Its role extends from basic research to clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical development, making it a cornerstone of modern biochemical analysis [1] [2].

Fundamental Principles of Gel Electrophoresis

The rate of migration and separation efficiency in gel electrophoresis are governed by several key factors [1]:

- Charge: The net charge of a protein determines its direction and rate of migration. Positively charged proteins (cations) move toward the cathode, while negatively charged proteins (anions) move toward the anode.

- Size and Shape: Larger proteins experience greater frictional drag and migrate slower through the gel matrix. Similarly, globular proteins may migrate differently than fibrous proteins of the same molecular weight.

- Gel Matrix Composition: The porosity of the gel, determined by its concentration and cross-linking, controls size-based separation. Polyacrylamide gels offer adjustable pore sizes suitable for protein separation.

- Buffer Conditions: pH determines the charge on proteins by influencing ionization of functional groups. Ionic strength affects conductivity and electroosmotic flow.

- Temperature: Increased temperature reduces buffer viscosity, potentially increasing migration rates but may also cause protein denaturation and affect separation reproducibility.

- Electric Field Strength: Higher voltages accelerate migration but can generate excessive heat, leading to band distortion and diffusion.

For proteins, which are amphoteric molecules containing both positive and negative charges, the buffer pH relative to the protein's isoelectric point (pI) is particularly crucial. When the buffer pH is below the pI, proteins carry a net positive charge and migrate toward the cathode. When the pH is above the pI, proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode [1].

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) for Protein Analysis

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) has become the standard method for protein separation due to its superior resolving power and chemical stability. The polyacrylamide gel matrix is formed through the copolymerization of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide (N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide), creating a cross-linked network with controllable pore sizes [2].

Key Variants of PAGE

- Native PAGE: Separates proteins under non-denaturing conditions, maintaining their native structure, biological activity, and complex formations. Separation depends on both the protein's intrinsic charge and size [2] [3].

- SDS-PAGE: Employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to denature proteins and impart a uniform negative charge. This eliminates the influence of native charge and shape, allowing separation based primarily on molecular weight [2].

- Two-Dimensional PAGE: Combines isoelectric focusing (separation by pI) in the first dimension with SDS-PAGE (separation by molecular weight) in the second dimension, providing extremely high resolution for complex protein mixtures [1].

- Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE): Specialized techniques for separating intact protein complexes, particularly mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes, under non-denaturing conditions. These methods provide insights into protein complex assembly, stoichiometry, and functional relationships [4].

Comparative Analysis of Electrophoresis Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Major Electrophoresis Techniques for Protein Analysis

| Technique | Resolution | Sensitivity | Speed | Throughput | Primary Protein Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slab Gel PAGE | High | Moderate | Moderate (1-4 hours) | Low to Moderate | Protein purity assessment, molecular weight determination, western blotting |

| Capillary Electrophoresis | Very High | High | Fast (minutes) | High | Pharmaceutical protein analysis, clinical diagnostics |

| Microchip Electrophoresis | High | High | Very Fast (<5 minutes) | Very High | High-throughput screening, point-of-care testing |

| Isotachophoresis | Moderate to High | High | Moderate | Moderate | Pre-concentration of dilute samples, sample preparation |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SDS-PAGE for Protein Analysis

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Composition/Preparation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide Solution | Forms the cross-linked gel matrix | Typically 29:1 or 37.5:1 ratio of acrylamide to bis-acrylamide; Neurotoxin in powder form - handle with gloves and mask [2] [3] |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Maintains stable pH during electrophoresis | Separating gel: pH 8.8; Stacking gel: pH 6.8 [2] |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge | Anionic detergent; typically 0.1% in gels and running buffer [2] |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) | Initiates polymerization reaction | Fresh aliquots recommended; store at -20°C [3] |

| TEMED | Catalyzes polymerization reaction | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine; added just before casting gels [2] |

| Running Buffer | Conducts current and maintains pH | Tris-Glycine buffer with 0.1% SDS, pH ~8.3 [2] |

| Loading Buffer | Prepares samples for application | Contains SDS, glycerol, bromophenol blue tracking dye, and β-mercaptoethanol or DTT [2] |

| Staining Solution | Visualizes separated protein bands | Coomassie Blue, Silver stain, or fluorescent dyes [2] |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Gel Preparation

Assemble Gel Casting Apparatus: Clean glass plates and spacers thoroughly, then assemble according to manufacturer's instructions to create a leak-proof seal.

Prepare Separating Gel: Mix appropriate volumes of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.8), SDS, TEMED, and APS according to the desired gel percentage and volume. The table below provides guidance on acrylamide concentrations for optimal separation of different protein size ranges [2] [3]:

Table 3: Polyacrylamide Gel Concentrations for Optimal Protein Separation

| % Acrylamide | Optimal Separation Range (kDa) | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| 8% | 30-200 | Large proteins |

| 10% | 20-100 | Standard separation |

| 12% | 10-70 | Small to medium proteins |

| 15% | 5-50 | Small proteins and peptides |

Pour Separating Gel: Transfer the solution into the gel cassette, leaving space for the stacking gel. Carefully overlay with isopropanol or water-saturated butanol to create a flat interface.

Polymerization: Allow the gel to polymerize completely (approximately 30 minutes). A distinct refractive interface will be visible when polymerization is complete.

Prepare Stacking Gel: Mix stacking gel solution containing acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 6.8), SDS, TEMED, and APS.

Pour Stacking Gel: Remove the overlay from the separating gel, rinse with deionized water, then pour the stacking gel and immediately insert a clean comb. Avoid air bubbles. Allow to polymerize for 30 minutes [2].

Sample Preparation and Loading

Prepare Protein Samples: Mix protein samples with loading buffer containing SDS and reducing agents (β-mercaptoethanol or DTT). Typical sample-to-buffer ratio is 4:1 [2].

Denature Proteins: Heat samples at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [2].

Load Samples: Place the polymerized gel into the electrophoresis chamber and fill with running buffer. Carefully remove the comb and rinse wells with running buffer. Load prepared samples into wells using a micropipette. Include appropriate molecular weight standards [2].

Electrophoresis and Visualization

Run Electrophoresis: Connect the apparatus to a power supply and run at constant voltage. Typical conditions: 80-100 V through stacking gel, 120-150 V through separating gel. Run until the tracking dye reaches the bottom of the gel [2].

Stain and Destain: After electrophoresis, carefully remove the gel from the plates and transfer to staining solution (e.g., Coomassie Blue) with gentle agitation for 30 minutes to overnight. Then destain to remove background stain and visualize protein bands [2].

Image and Analyze: Document the gel using a gel documentation system and analyze band intensities using software such as GelAnalyzer, ImageJ, or AI-powered tools like GelGenie [5] [6].

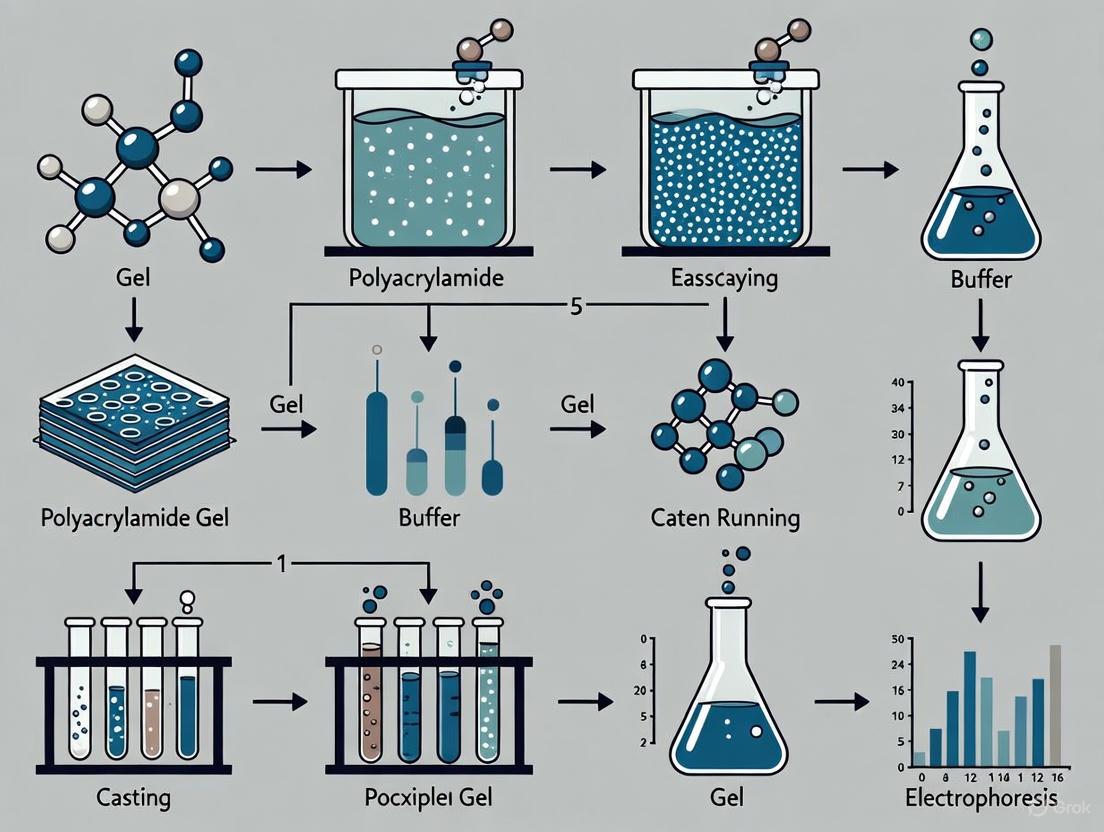

SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow

Advanced Applications in Protein Research

Protein Quantification and Detection

Traditional protein quantification based on SDS-PAGE with staining has limitations in accuracy and dynamic range. Recent advancements have addressed these challenges through innovative approaches:

Intrinsic Fluorescence Imaging: An improved gel electrophoresis tank with online intrinsic fluorescence imaging enables real-time protein detection without staining, expanding the detection window to 10 lanes. This method demonstrates a limit of detection of 14 ng, limit of quantification of 42 ng, and a dynamic range of 50-8000 ng for bovine serum albumin (BSA) in complex samples [7].

Gaussian Fitting Arithmetic: This computational approach improves quantification accuracy from low-resolution gel images by modeling band signals as a sum of Lorentzian peaks, providing a close fit to experimental conditions. Validation studies showed recoveries of 106.37% for urine samples and 94.96% for whey samples, with intra-day and inter-day RSD values of 9.17% and 10.06% respectively [7].

Analysis of Protein Complexes

Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear-Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) have become indispensable tools for studying mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes and other membrane protein complexes. These techniques [4]:

- Resolve individual OXPHOS complexes and respiratory chain supercomplexes

- Enable analysis of assembly pathways of multi-subunit complexes

- Reveal pathologic mechanisms in patients with monogenetic OXPHOS disorders

- Allow in-gel enzyme activity staining for Complexes I, II, IV, and V

Recent protocol improvements have shortened sample extraction procedures and enhanced sensitivity of in-gel Complex V activity staining, providing robust, semi-quantitative, and reproducible results for characterizing native protein complexes [4].

Emerging Trends and Technological Advancements

The field of gel electrophoresis continues to evolve with several emerging trends enhancing its capabilities for protein analysis:

AI-Powered Image Analysis

Traditional gel image analysis methods have remained largely unchanged for decades, relying on manual processes or semi-automated algorithms that often miss bands, generate false positives, or inaccurately identify band edges. Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence are revolutionizing this field [5]:

GelGenie Framework: An AI-powered system using U-Net architectures trained on 500+ manually-labelled gel images can automatically identify gel bands in seconds across wide experimental conditions. The system performs pixel-level segmentation, classifying each pixel as 'band' or 'background', enabling accurate band identification even in sub-optimal conditions with warped bands, high background, gel contaminants, or diffuse bands [5].

Performance Validation: When applied to gel electrophoresis data from external laboratories, GelGenie generates results that quantitatively match those of the original authors, demonstrating its robustness and accuracy. The models are publicly available through an open-source application that requires no expert knowledge [5] [8].

Integration with Other Analytical Techniques

Modern electrophoresis increasingly combines with other powerful analytical methods:

Mass Spectrometry Coupling: Following separation by 2D-PAGE or other electrophoretic techniques, protein spots can be excised and identified by mass spectrometry, enabling comprehensive proteomic analysis [1].

Microfluidics Integration: The combination of electrophoresis with microfluidic devices enables high-throughput analysis, reduced sample requirements, and rapid results, particularly valuable in clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical screening [1].

Modern Gel Electrophoresis Integration

Gel electrophoresis remains an indispensable technique for protein analysis due to its proven reliability, adaptability, and continuing technological evolution. From its foundational role in basic protein characterization to its advanced applications in complex system analysis and integration with cutting-edge computational methods, electrophoresis continues to provide critical insights into protein structure, function, and interactions.

The ongoing development of AI-powered analysis tools, enhanced detection methods, and integration with other analytical platforms ensures that gel electrophoresis will maintain its essential position in the researcher's toolkit. As these advancements address traditional limitations in quantification accuracy, throughput, and user accessibility, gel electrophoresis is poised to continue as a cornerstone technique supporting discoveries across biochemistry, molecular biology, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical development.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) remains a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry laboratories worldwide, providing the foundation for protein separation and analysis. The efficacy of this technique hinges on the precise chemical structure of the polyacrylamide gel, which functions as a molecular sieve to separate biomolecules based on size and charge. This application note examines the fundamental chemistry of how acrylamide and bis-acrylamide co-polymerize to form a porous matrix, details optimized protocols for gel preparation, and provides troubleshooting guidance for common issues. Understanding these chemical principles is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to optimize protein electrophoresis for their specific research needs, from basic protein characterization to complex proteomic analyses.

The Chemical Foundation of Polyacrylamide Gels

Monomer Composition and Polymerization Chemistry

The molecular sieve properties of polyacrylamide gels originate from the specific chemical interaction between two monomers: acrylamide and N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (bis-acrylamide). Acrylamide forms the primary backbone of the polymer matrix, while bis-acrylamide serves as the crosslinking agent that connects adjacent polyacrylamide chains [9]. This crosslinked structure creates a porous network through which proteins migrate during electrophoresis.

The polymerization reaction is catalyzed by a free-radical system involving ammonium persulfate (APS) as the initiator and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) as the catalyst [10]. TEMED catalyzes the formation of free radicals from APS, which then initiate the polymerization of acrylamide monomers into long linear chains. The bis-acrylamide molecules, containing two acrylamide functional groups, incorporate into these growing chains and form cross-bridges between them, creating the characteristic three-dimensional mesh structure [10]. The resulting matrix is stable, chemically inert, and provides defined pore sizes that enable size-based separation of protein molecules.

Controlling Pore Size for Optimal Separation

The porosity of the gel matrix is precisely controlled by adjusting two key parameters: the total acrylamide concentration (%T) and the crosslinker ratio (%C). The total acrylamide concentration (%T) represents the combined mass of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide per 100 mL of solution and primarily determines the average pore size [9]. Higher %T values create denser matrices with smaller pores, which are ideal for separating lower molecular weight proteins. Conversely, lower %T values produce larger pores better suited for resolving higher molecular weight proteins [11].

The crosslinker ratio (%C) represents the proportion of bis-acrylamide relative to the total acrylamide content and affects the rigidity and porosity of the final gel structure. Standard protocols typically use a crosslinker ratio of 1-5% depending on the desired separation characteristics [12]. This precise control over matrix porosity enables researchers to tailor the gel composition to their specific protein separation needs, optimizing resolution across a wide molecular weight range.

Table 1: Optimal Acrylamide Concentrations for Separating Proteins of Different Sizes

| Protein Size (kDa) | Recommended Acrylamide Percentage |

|---|---|

| 4-40 | 20% |

| 12-45 | 15% |

| 10-70 | 12.5% |

| 15-100 | 10% |

| 25-200 | 8% |

Experimental Protocols

Reagent Preparation and Standard Formulations

Proper reagent preparation is fundamental to reproducible gel polymerization and optimal electrophoretic separation. The foundational component for most PAGE applications is a 30% acrylamide-bisacrylamide stock solution, typically prepared at a ratio of 29:1 or 37.5:1 (acrylamide:bis-acrylamide) [12]. This stock solution should be stored in dark bottles at 4°C to prevent spontaneous polymerization and decomposition.

The electrophoresis running buffer for SDS-PAGE typically consists of Tris-Glycine with 0.1% SDS, maintaining a pH of approximately 8.3-8.5 to facilitate protein migration toward the anode [10]. For specialized applications such as histidine-imidazole PAGE (HI-PAGE) for lipoprotein analysis, alternative buffer systems may be employed, such as Tris-histidine at pH 8.4 [13]. Sample loading buffer should contain SDS to denature proteins, a reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to break disulfide bonds, glycerol to density-load samples into wells, and a tracking dye (bromophenol blue) to monitor migration progress [11].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Function | Standard Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-Bis Solution | Forms the porous polymer matrix | 30% (w/v) in water, 29:1 or 37.5:1 ratio |

| TEMED | Catalyzes polymerization | Neat liquid, used at 0.1-0.2% final concentration |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates free-radical polymerization | 10% (w/v) solution in water, freshly prepared |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform charge | 10% (w/v) solution in water |

| Tris Buffer | Maintains pH during electrophoresis | 1.5 M pH 8.8 (resolving gel), 0.5 M pH 6.8 (stacking gel) |

| Running Buffer | Conducts current and maintains pH | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS (w/v), pH 8.3 |

Step-by-Step Gel Casting Protocol

The following protocol details the preparation of a standard SDS-polyacrylamide gel with a stacking gel system for optimal protein separation [12] [2]:

Assemble the gel cassette: Clean glass plates with ethanol or industrial methylated spirit and assemble the casting apparatus according to manufacturer instructions, ensuring a tight seal to prevent leakage.

Prepare the resolving gel: Combine acrylamide-bis solution, Tris buffer (pH 8.8), SDS, and water in the specified volumes for the desired acrylamide percentage. Add TEMED and 10% APS last, mixing gently to avoid introducing air bubbles. Immediately pipette the solution into the gel cassette, leaving appropriate space for the stacking gel.

Overlay with isopropanol: Carefully add a layer of isopropanol or water-saturated butanol on top of the resolving gel to create a flat interface and exclude oxygen, which inhibits polymerization. Allow the gel to polymerize for 30-45 minutes at room temperature.

Prepare and add the stacking gel: After polymerization, pour off the isopropanol and rinse the gel surface with distilled water. Wick away excess liquid with lint-free tissue. Prepare the stacking gel mixture containing acrylamide, Tris buffer (pH 6.8), SDS, water, TEMED, and APS. Pour onto the resolving gel and immediately insert a clean comb, avoiding air bubbles. Allow to polymerize for 30 minutes.

Store or use the polymerized gel: Once polymerized, carefully remove the comb and rinse wells with running buffer. Gels can be used immediately or wrapped in moist tissue and plastic film for storage at 4°C for up to several weeks.

Electrophoresis Parameters and Run Conditions

For optimal protein separation, load denatured protein samples (heated at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes in loading buffer) into the wells alongside appropriate molecular weight markers [2]. Fill the electrophoresis chamber with running buffer, ensuring the upper and lower chambers are properly connected. Apply a constant voltage of 100-150V for mini-gel systems, adjusting based on gel thickness and acrylamide percentage [14] [11]. Run the gel until the dye front reaches approximately 1 cm from the bottom, typically requiring 60-90 minutes depending on the conditions. To prevent smiling effects (curved bands) and overheating, run gels at lower voltages in a cold room or using apparatus with cooling capabilities [14].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Despite the standardized protocols, researchers may encounter several common issues during polyacrylamide gel preparation and electrophoresis. The table below outlines these challenges, their potential causes, and recommended solutions based on established troubleshooting guidelines [14] [11]:

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared bands | Voltage too high; incomplete denaturation | Run gel at lower voltage (10-15 V/cm); ensure proper sample boiling with adequate SDS and DTT |

| Poor band separation | Gel percentage inappropriate for target protein size; insufficient run time | Use lower % gel for high MW proteins, higher % for low MW proteins; run until dye front reaches bottom |

| Smiling bands (curved bands) | Excessive heat generation during run | Run gel at lower voltage for longer time; use cooling apparatus or cold room |

| Distorted bands in peripheral lanes | Edge effect from empty wells | Load protein or ladder in all wells; avoid leaving wells empty |

| Protein samples migrating out of wells before run | Delay between loading and starting electrophoresis | Minimize time between loading and applying current; load samples quickly and consistently |

| Incomplete polymerization | Old or improperly prepared APS; insufficient TEMED | Use fresh APS prepared weekly; ensure adequate TEMED concentration; check reagent quality |

Additional issues may include vertical streaking, which often results from protein aggregation or precipitation, remedied by ensuring complete sample denaturation and reducing protein load [11]. If bands appear compressed or poorly resolved in specific regions of the gel, consider using gradient gels with increasing acrylamide concentration to improve resolution across a broader molecular weight range [10]. For persistent polymerization problems, systematically replace reagents to identify degraded components, as acrylamide solutions decompose over time, especially when improperly stored.

Advanced Applications and Methodological Variations

The versatility of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis extends beyond standard SDS-PAGE, with several advanced applications leveraging the molecular sieve properties of the acrylamide-bis matrix. Native PAGE separates proteins in their non-denatured state, maintaining biological activity and higher-order structure by omitting SDS from the buffer system [10]. This technique separates proteins based on both size and inherent charge, enabling studies of protein complexes and functional interactions.

Two-dimensional PAGE combines isoelectric focusing (IEF) with SDS-PAGE to provide extremely high resolution separation of complex protein mixtures [10]. In this technique, proteins are first separated based on their isoelectric point in a pH gradient, then further resolved by molecular weight in the second dimension, creating a two-dimensional protein map where each spot represents an individual protein species.

Specialized applications continue to emerge, such as fluorescence-based histidine-imidazole PAGE (fHI-PAGE) for lipoprotein analysis, which provides rapid separation and quantification of lipoprotein fractions within one hour without band distortion [13]. Such methodological innovations demonstrate the continued utility and adaptability of polyacrylamide gel systems for diverse research applications in biochemistry and clinical diagnostics.

Within the broader context of preparing polyacrylamide gels for protein electrophoresis research, selecting the appropriate electrophoretic technique is a fundamental decision that directly determines the success and validity of an experiment. The choice between SDS-PAGE (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) and Native PAGE (Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) dictates whether proteins will be analyzed in a denatured state, separated solely by molecular mass, or in their native, functional conformation, separated by a combination of size, charge, and shape [15] [16]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these two core techniques, including structured data tables, step-by-step protocols, and visualization tools to guide researchers and drug development professionals in making an informed choice aligned with their research objectives.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

SDS-PAGE is a denaturing technique where the anionic detergent SDS binds to proteins, unfolds them, and imparts a uniform negative charge. This masks the proteins' intrinsic charge and eliminates the influence of shape, resulting in separation based almost exclusively on molecular weight [15] [16]. Consequently, proteins lose their biological activity, making this method ideal for determining molecular weight, assessing purity, and analyzing subunit composition [16].

In contrast, Native PAGE is a non-denaturing technique. It is performed without SDS or reducing agents, preserving the protein's native conformation, multi-subunit structure, and biological activity [15] [17]. Separation depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape, allowing researchers to study functional protein complexes, oligomerization states, and enzymatic activity [15] [16].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight [15] | Size, overall charge, and shape [15] |

| Protein State | Denatured and unfolded [15] [16] | Native, folded, and functional [15] [16] |

| Key Reagents | SDS, reducing agent (e.g., DTT) [15] [17] | Non-denaturing buffers; no SDS [15] [17] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated (typically 85°C for 2 min) [15] [17] | Not heated [15] [17] |

| Protein Function Post-Run | Lost [15] | Retained [15] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity check, protein expression analysis [15] | Studying protein structure, subunit composition, function, and protein-protein interactions [15] [16] |

A Decision Framework for Technique Selection

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical process for choosing between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE based on the research goal.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for SDS-PAGE

This protocol is adapted for a standard mini-gel format using a pre-cast Tris-Glycine gel [17].

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute your protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer to a final 1X concentration [17].

- For reduced conditions, add a reducing agent like dithiothreitol (DTT) to a final concentration of 50 mM [17].

- Heat the samples at 85°C for 2 minutes to denature the proteins [17]. Cool briefly before loading.

Electrophoresis:

- Remove a pre-cast gel from its pouch and rinse the cassette with deionized water. Remove the comb and rinse the wells with 1X Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer [17].

- Assemble the gel in the electrophoresis chamber according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Fill the inner (upper) and outer (lower) buffer chambers with 1X Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer [17].

- Load the prepared samples and an appropriate protein molecular weight marker into the wells.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 125 V until the dye front (bromophenol blue) reaches the bottom of the gel (approximately 90 minutes) [17].

Protocol for Native PAGE

This protocol describes a Native PAGE method using a Tris-Glycine system and pre-cast gels, suitable for analyzing protein oligomers [17] [18].

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute your protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer to a final 1X concentration [17].

- Do not add SDS, reducing agents, or heat the sample [15] [17]. Keep samples on ice to maintain native structure.

Electrophoresis:

- Prepare a pre-cast non-denaturing gel or cast a Tris-Glycine polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 7.5% separation gel, 4.5% stacking gel) [18].

- Assemble the gel in the electrophoresis chamber.

- Fill the buffer chambers with 1X Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH ~8.8) [17] [18]. Note: The running buffer for native electrophoresis does not contain SDS.

- Load the prepared native samples and markers.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 125 V for 1-12 hours, depending on the protein system [17] [18]. The run time is typically longer than for SDS-PAGE due to the lack of a uniform charge from SDS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of protein electrophoresis relies on a set of key reagents, each with a specific function in sample preparation and separation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PAGE

| Reagent | Function | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [15] | Essential | Not Used |

| Reducing Agent (DTT/BME) | Breaks disulfide bonds for complete denaturation [15] [17] | Used (in reducing gels) | Not Used |

| Tris-Glycine SDS Buffer | Provides ionic environment for denatured protein separation [17] | Essential | Not Used |

| Tris-Glycine Native Buffer | Provides ionic environment for native protein separation [17] [18] | Not Used | Essential |

| Crosslinker (Bis-Acrylamide) | Forms the crosslinked network of the polyacrylamide gel matrix [19] [20] | Essential | Essential |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes the polymerization of the polyacrylamide gel [20] | Essential | Essential |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Understanding how to interpret the results from each technique is critical. A classic example involves identifying a protein's quaternary structure.

Scenario: A protein sample runs as a 60 kDa band on non-reducing SDS-PAGE but migrates at 120 kDa on Native PAGE [21].

Inference: The protein is a dimer of 60 kDa subunits that are not linked by disulfide bonds. The non-reducing SDS-PAGE conditions would have left disulfide bonds intact; the fact that it still runs as a monomer indicates the dimer is held together by non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrophobic, ionic) that are disrupted by SDS. In Native PAGE, the protein remains in its native, dimeric form, resulting in a larger apparent size [21].

Advanced Applications: Native PAGE Variants

For specialized analyses of complex protein assemblies, particularly mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes, advanced Native PAGE variants are used.

- Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE): Uses Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye, which binds to protein complexes and imparts a negative charge proportional to their mass, allowing separation in a native state. It is ideal for analyzing the size, abundance, and composition of large, multi-subunit complexes and their supercomplexes [4] [22].

- Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE): A related technique that separates protein complexes based on their intrinsic charge in a gradient gel without using Coomassie dye [15] [4]. These techniques can be coupled with a second-dimension SDS-PAGE to resolve the individual subunits of the complexes separated in the first dimension [4] [22].

SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE are complementary pillars of protein analysis. The decision between them rests squarely on the research question. SDS-PAGE is the tool of choice for determining molecular weight, analyzing purity, and characterizing denatured proteins. Native PAGE is indispensable for probing the functional state of proteins, revealing oligomeric structures, and studying interactions within protein complexes. By applying the guidelines, protocols, and interpretive frameworks outlined in this application note, researchers can confidently select and execute the optimal electrophoretic strategy for their work in biochemistry and drug development.

The Critical Role of SDS, Tris Buffers, APS, and TEMED in the Electrophoresis System

Application Note

In the preparation of polyacrylamide gels for protein electrophoresis, a precise understanding of the function and application of key reagents is fundamental to experimental success. This note details the critical roles of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), Tris buffers, Ammonium Persulfate (APS), and Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) within the SDS-PAGE system. When used in concert, these reagents create the conditions necessary for the reliable separation of proteins based on their molecular weight, a cornerstone technique in biochemical research and drug development [23] [24]. The integrity of the gel matrix and the fidelity of protein migration are directly controlled by the quality, concentration, and handling of these components.

The foundation of the gel is formed by acrylamide and bisacrylamide, which copolymerize into a porous matrix. The pore size, which dictates the resolution of protein separation, is determined by the percentage of acrylamide used; higher percentages create smaller pores for better resolution of lower molecular weight proteins [24]. Within this system, Tris buffers establish and maintain the stable pH environment required for consistent protein migration and gel polymerization. APS and TEMED, the polymerization catalysts, are the engines of gel formation, initiating and propagating the free-radical reaction that solidifies the gel solution [23]. Finally, SDS is the great equalizer, binding to proteins and conferring upon them a uniform negative charge, which allows their separation to be based almost exclusively on molecular weight [24]. Any deviation in the preparation or quality of these reagents can lead to experimental artifacts, including poor band resolution, smearing, or incomplete polymerization, underscoring their non-negotiable role in the protocol [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents for SDS-PAGE, detailing their specific functions in the electrophoresis system.

Table 1: Key Reagents for SDS-PAGE Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis

| Reagent | Function in the Electrophoresis System |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, allowing separation based primarily on molecular weight [24]. |

| Tris Buffers | Provides the necessary buffering capacity to maintain a stable pH during electrophoresis and gel polymerization (e.g., pH 8.8 for resolving gel, pH 6.8 for stacking gel) [23] [24]. |

| APS (Ammonium Persulfate) | Initiates the polymerization reaction of acrylamide and bisacrylamide by generating free radicals [23]. |

| TEMED | Catalyzes the polymerization reaction by accelerating the rate of free-radical formation from APS, leading to gel solidification [23]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the porous polyacrylamide gel matrix when polymerized; the ratio and concentration determine the gel's pore size and separation properties [24]. |

| Glycerol | Adds density to the sample buffer, ensuring samples sink to the bottom of the well during loading [23]. |

| Bromophenol Blue | A tracking dye that migrates ahead of the proteins, allowing visual monitoring of the electrophoresis progress [26]. |

| Coomassie Blue | A dye used for staining proteins after electrophoresis to visualize separated protein bands [26]. |

Quantitative Data Specifications

Precise formulation of gel components is critical for reproducibility. The following tables provide standard recipes for a 15% resolving gel and a 5% stacking gel, optimized for a 10 mL and 3 mL total volume, respectively [23].

Table 2: Formulation for a 15% Resolving Gel (10 mL total volume)

| Component | Volume | Final Concentration/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Deionized Water | 2.3 mL | Solvent |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis | 5.0 mL | 15% gel matrix |

| 1.5 M Tris, pH 8.8 | 2.5 mL | ~0.375 M Tris, resolving pH |

| 10% SDS | 0.1 mL | 0.1% SDS |

| 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 0.1 mL | Polymerization initiator |

| TEMED | 0.004 mL | Polymerization catalyst |

Table 3: Formulation for a 5% Stacking Gel (3.0 mL total volume)

| Component | Volume | Final Concentration/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Deionized Water | 2.1 mL | Solvent |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis | 0.5 mL | 5% gel matrix |

| 1.0 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | 0.38 mL | ~0.127 M Tris, stacking pH |

| 10% SDS | 0.03 mL | 0.1% SDS |

| 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 0.03 mL | Polymerization initiator |

| TEMED | 0.003 mL | Polymerization catalyst |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: SDS-PAGE Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis

I. Gel Preparation

- Assemble Casting Chamber: Clean and dry the glass plates and spacers. Assemble the casting stand according to the manufacturer's instructions to create a leak-proof chamber [24].

- Prepare Resolving Gel Solution: In a beaker or flask, combine all reagents for the resolving gel (see Table 2) except for TEMED and APS. Mix gently using a Pasteur pipette to avoid introducing air bubbles [23].

- Catalyze and Pour Resolving Gel: Add the specified volumes of 10% APS and TEMED to the solution. Swirl gently to mix. Immediately transfer the solution between the glass plates in the casting chamber, filling to about ¾ of the total height.

- Overlay and Polymerize: Carefully add a small layer of absolute ethanol or isobutyl alcohol on top of the gel solution to exclude oxygen and create a flat interface. Allow the gel to polymerize completely, which should occur within 5-30 minutes. Once polymerized, pour off the overlay, rinse with water, and absorb residual liquid with a Kimwipe or filter paper [23] [26].

- Prepare and Pour Stacking Gel: In a new container, combine all reagents for the stacking gel (see Table 3) except APS and TEMED. Add APS and TEMED, mix, and pour the solution directly onto the polymerized resolving gel. Immediately insert a clean comb into the stacking gel, avoiding air bubbles. Allow to polymerize for 20-30 minutes [23] [24].

II. Sample Preparation

- Denature Protein Samples: Mix the protein sample with an appropriate volume of Laemmli sample buffer (e.g., a 4x concentration). A typical ratio is 3 parts protein solution to 1 part 4x sample buffer [23].

- Heat Denaturation: Cap the tubes and boil the samples at 95-100°C for 5-10 minutes to fully denature the proteins [24].

- Centrifuge: Briefly centrifuge the denatured samples to collect condensation and bring the entire volume to the bottom of the tube.

III. Electrophoresis

- Set Up Apparatus: Remove the comb gently and rinse the wells with 1X electrophoresis buffer. Place the gel cassette into the electrode assembly and slide the assembly into the tank. Fill the inner and outer chambers with 1X electrophoresis buffer [23].

- Load Samples: Using a gel-loading micropipette, slowly load 20 µL of the denatured protein samples or molecular weight marker into the wells [23].

- Run Gel: Place the lid on the tank, aligning the electrodes correctly. Connect to a power supply and run the gel at a constant voltage of 80V until the dye front enters the resolving gel. Then, increase the voltage to 120V until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel. This process typically takes 1-2 hours [23].

- Stain and Destain: After electrophoresis, carefully disassemble the apparatus and remove the gel. Visualize proteins by staining with Coomassie Blue staining solution for several hours or overnight with gentle shaking. Destain with a destaining solution (e.g., 10% acetic acid, 10% methanol) until the background is clear and protein bands are visible [26].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

The following table outlines common problems, their causes, and solutions related to key reagents and the electrophoresis process [25].

Table 4: Troubleshooting Guide for SDS-PAGE

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Band Resolution | Gel concentration is incorrect for target protein size. | Use a gradient gel (e.g., 4%-20%) if protein size is unknown, or adjust acrylamide % [25]. |

| Current/voltage is too high, causing "band smiling." | Decrease the voltage by 25-50% [25]. | |

| Band Smearing | Protein concentration is too high. | Reduce the amount of protein loaded on the gel [25]. |

| Voltage is too high. | Decrease the voltage by 25-50% [25]. | |

| Gel Does Not Polymerize | TEMED and/or APS are degraded or were forgotten. | Use fresh APS and TEMED; ensure they are added to the gel mixture [25]. |

| The temperature is too low. | Cast the gel at room temperature [25]. | |

| Samples Do Not Sink | Insufficient glycerol in sample buffer. | Ensure sample buffer contains glycerol (e.g., 2-5%) [25]. |

| Skewed/Distorted Bands | Polymerization around wells was poor or uneven. | Increase the amount of APS and TEMED slightly; ensure gel solution is mixed thoroughly and poured without bubbles [25]. |

| Protein Aggregation | Insufficient reducing agent; hydrophobic proteins. | Prepare fresh sample buffer with fresh DTT or β-mercaptoethanol; for hydrophobic proteins, add 4-8 M urea to the sample [25]. |

SDS-PAGE Workflow and Reagent Roles

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow of an SDS-PAGE experiment, highlighting the critical points where the four key reagents (SDS, Tris, APS, TEMED) perform their essential functions.

SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow

How Gel Percentage and Pore Size Dictate Protein Separation by Molecular Weight

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental tool in molecular biology and proteomics for separating protein mixtures based on their molecular weights. The efficacy of this separation hinges primarily on the polyacrylamide gel matrix, which functions as a molecular sieve [10]. This application note delineates the quantitative relationship between gel percentage, resultant pore size, and protein separation range, providing researchers with detailed protocols and frameworks to optimize electrophoretic conditions for specific experimental requirements. Understanding these principles is essential for preparing gels that yield high-resolution protein separation, a cornerstone technique in protein characterization, purity assessment, and proteomic analysis [10] [27].

The polyacrylamide gel matrix is formed through the copolymerization of acrylamide and a cross-linking agent, typically N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (bis-acrylamide) [10]. The pore size of this three-dimensional network is inversely related to the total percentage of acrylamide, with higher percentages creating smaller pores that retard the migration of larger proteins [10]. This principle allows researchers to selectively tailor gel compositions to target specific molecular weight ranges of interest.

Theoretical Foundation: The Gel Matrix as a Molecular Sieve

Polyacrylamide Gel Formation and Pore Structure

The polyacrylamide gel matrix is created through a free radical polymerization reaction. Acrylamide monomers form the backbone of the polymer chains, while bis-acrylamide molecules covalently link these chains together, creating a cross-linked network [10] [28]. The polymerization is catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS), which provides the free radicals, and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), which accelerates the radical formation [10]. The resulting gel possesses a three-dimensional mesh with pores through which proteins migrate under the influence of an electric field.

The pore size within this matrix is determined by two key factors: the total concentration of acrylamide (%T) and the degree of cross-linking (%C, representing the proportion of bis-acrylamide relative to total acrylamide) [10]. Standard protocols often use a bis-acrylamide to acrylamide ratio of 1:29, but this can be adjusted to modify the gel's mechanical properties and pore size distribution [10].

The Role of SDS in Protein Separation

In SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays a crucial role in normalizing protein charge. Proteins are denatured by heating in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol), which cleaves disulfide bonds [10] [27]. SDS binds to the denatured polypeptides in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein), conferring a uniform negative charge density [10] [27]. This process neutralizes the proteins' intrinsic charges and unfolds them into linear chains, transforming molecular weight separation into the primary factor governing electrophoretic mobility [29].

The following diagram illustrates the molecular separation mechanism in SDS-PAGE:

Discontinuous Buffer System

Most SDS-PAGE systems employ a discontinuous (or disc) buffer system that enhances separation resolution. This system comprises two distinct gel layers with different pore sizes and pH values: a stacking gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide, pH 6.8) and a resolving gel (varying percentages, pH 8.8) [10] [29]. The stacking gel concentrates protein samples into sharp bands before they enter the resolving gel, where actual separation occurs based on molecular size [29]. This process is facilitated by differences in ionic composition and pH between the stacking gel, resolving gel, and running buffer, creating a transient state where proteins focus into narrow zones [29].

Quantitative Relationships: Gel Percentage vs. Protein Separation

Optimal Acrylamide Percentages for Protein Separation

The appropriate acrylamide concentration depends directly on the molecular weight range of the target proteins. Lower percentage gels (e.g., 8-10%) with larger pores are optimal for resolving high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentage gels (e.g., 12-15%) with smaller pores provide better separation of lower molecular weight proteins [10]. Gradient gels, which contain a continuous increase in acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-20%), extend the separation range across a broader spectrum of molecular weights within a single gel [10].

Table 1: Recommended Polyacrylamide Gel Percentages for Protein Separation by Molecular Weight

| Gel Percentage (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Optimal Application |

|---|---|---|

| 6-8% | 50-150 | Very high molecular weight proteins |

| 10% | 20-100 | Standard mixture of proteins |

| 12% | 10-60 | Most common range for protein analysis |

| 15% | 5-45 | Low molecular weight proteins and peptides |

Mathematical Relationship and Ferguson Analysis

The relationship between protein mobility (Rf) and gel concentration follows a logarithmic function described by the Ferguson equation: log(Rf) = log(Ro) - Kr × %T, where Rf represents the relative mobility of the protein, Ro is the free electrophoretic mobility, Kr is the retardation coefficient, and %T is the total acrylamide concentration. This mathematical relationship demonstrates that electrophoretic mobility decreases exponentially with increasing gel concentration, with larger proteins exhibiting steeper declines in mobility (higher Kr values) due to greater steric hindrance within the gel matrix.

Table 2: Separation Characteristics of Different Gel Configurations

| Gel Type | Total Acrylamide | Pore Size | Separation Principle | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturing SDS-PAGE | Variable %T | Determined by %T | Molecular weight | Most protein analyses; mass determination |

| Native PAGE | Variable %T | Determined by %T | Size, charge, shape | Active enzyme assays; protein complexes |

| Gradient Gels | Increasing %T | Decreasing pore size | Molecular weight | Broad range separation in single gel |

| Two-Dimensional PAGE | Fixed or gradient %T | Fixed or variable | pI (1D), mass (2D) | Comprehensive proteomic analysis |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Casting a Standard SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel

This protocol details the preparation of a discontinuous SDS-polyacrylamide gel with a 12% resolving gel and 5% stacking gel, suitable for separating proteins in the 10-60 kDa range [10] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Polyacrylamide Gel Preparation

| Reagent | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Gel matrix formation | Neurotoxin in monomer form; use pre-made solutions |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | pH control | Different concentrations for stacking (pH 6.8) and resolving (pH 8.8) gels |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Protein denaturation/detergent | Provides uniform negative charge to proteins |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Polymerization initiator | Freshly prepared solutions recommended |

| TEMED | Polymerization catalyst | Accelerates free radical formation from APS |

| Butanol/isopropanol | Gel surface dehydration | Creates flat interface for stacking gel |

Resolving Gel Preparation

- Gel Solution Composition: For a 12% resolving gel, combine the following components in a clean flask: 4.0 mL of 30% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution (29:1), 2.5 mL of 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 3.4 mL of distilled water, 100 μL of 10% SDS, 50 μL of 10% ammonium persulfate, and 10 μL of TEMED [10].

- Casting: Mix gently and immediately pipette the solution between assembled glass plates, leaving space for the stacking gel (approximately 2 cm from the top).

- Overlay: Carefully overlay the gel solution with saturated butanol or isopropanol to exclude oxygen and create a flat meniscus.

- Polymerization: Allow the gel to polymerize completely (approximately 20-30 minutes at room temperature). A distinct refractive interface will form between the gel and overlay solution.

Stacking Gel Preparation

- Gel Solution Composition: For a 5% stacking gel, combine: 0.67 mL of 30% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution (29:1), 0.5 mL of 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2.8 mL of distilled water, 40 μL of 10% SDS, 30 μL of 10% ammonium persulfate, and 5 μL of TEMED [10].

- Casting: After removing the overlay from the polymerized resolving gel, pipette the stacking gel solution onto the resolving gel.

- Comb Insertion: Immediately insert a clean sample comb without introducing air bubbles.

- Polymerization: Allow complete polymerization (approximately 15-20 minutes).

The complete workflow for protein separation analysis is summarized below:

Protocol 2: Sample Preparation and Electrophoretic Conditions

Protein Sample Preparation

- Sample Buffer: Combine protein sample with 2× Laemmli buffer (typically containing: 62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 25% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue, with 5% β-mercaptoethanol or 100 mM DTT added fresh for reduction) [27] [29].

- Denaturation: Heat samples at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [27].

- Loading: Centrifuge briefly to collect condensation, then load 10-20 μL per well (typically 10-30 μg total protein for complex mixtures).

Electrophoresis Conditions

- Buffer System: Fill electrophoresis chamber with Tris-glycine running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [27].

- Voltage Parameters: Apply constant voltage: 80 V during stacking phase (approximately 20-30 minutes until dye front enters resolving gel), then increase to 120-150 V for separation (1-2 hours, until dye front reaches bottom of gel) [27] [30].

- Termination: Stop electrophoresis before the bromophenol blue tracking dye migrates off the bottom of the gel.

Protocol 3: Post-Electrophoresis Analysis

Protein Staining and Visualization

- Fixation: For Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, immerse gel in fixative solution (40% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) for 30-60 minutes.

- Staining: Transfer to Coomassie staining solution (0.1% Coomassie R-250 in 40% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) for 1-2 hours with gentle agitation.

- Destaining: Remove background stain with destaining solution (40% ethanol, 10% acetic acid) until protein bands are clear against a transparent background.

- Documentation: Capture digital images using gel documentation systems with white light illumination [31].

Molecular Weight Determination

- Molecular Weight Markers: Include prestained or unstained protein standards in at least one lane [10].

- Standard Curve: Plot log(molecular weight) of standards versus relative mobility (Rf = migration distance of protein / migration distance of dye front).

- Interpolation: Determine unknown protein molecular weights by interpolation from the standard curve. Typical accuracy is ±10% [27].

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Gradient Gels for Enhanced Separation Range

Gradient gels provide a continuous increase in acrylamide concentration from top to bottom (e.g., 4-20%), creating a decreasing pore size gradient [10]. This configuration offers several advantages: (1) broader separation range within a single gel, (2) automatic stacking effect without need for a separate stacking gel, and (3) sharper protein bands as molecules slow down progressively in regions of appropriately sized pores [10]. Gradient gels are particularly valuable for analyzing complex protein mixtures with components spanning a wide molecular weight spectrum.

Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional PAGE (2D-PAGE) separates proteins by two distinct properties: isoelectric point (pI) in the first dimension using isoelectric focusing (IEF), followed by molecular weight separation in the second dimension using standard SDS-PAGE [10]. This technique provides the highest resolution for protein analysis, capable of resolving thousands of proteins from a single sample, making it indispensable for comprehensive proteomic studies [10] [32]. Specialized computational tools like MatGel have been developed to automate the quantification of protein spots in 2D-PAGE images, enhancing throughput and reducing manual errors [32].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Smearing Bands: Can result from protein overload, incomplete denaturation, too high voltage causing overheating, or gel imperfections [31] [30].

- Atypical Migration: Post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) can alter SDS binding and thus electrophoretic mobility [29].

- Poor Resolution: Optimize acrylamide percentage for target protein size range, ensure fresh electrophoresis buffers, and verify appropriate running conditions [31].

The precise control of polyacrylamide gel percentage represents a fundamental parameter in optimizing protein separation by molecular weight. The direct relationship between acrylamide concentration, pore size, and separation range enables researchers to strategically design electrophoretic conditions tailored to their specific protein targets. The protocols outlined in this application note provide a systematic approach to gel preparation, sample processing, and analysis that ensures reproducible, high-resolution protein separation. Mastery of these techniques forms an essential foundation for advanced proteomic investigations and biomarker discovery in both research and drug development contexts.

Step-by-Step Protocol: Casting and Running a Protein Gel for Optimal Results

For researchers in protein biochemistry and drug development, the integrity of polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is foundational. The process begins at the casting station, where the quality of the gel is determined. Proper setup and reagent preparation are critical for achieving high-resolution protein separation, which underpins accurate analysis in western blotting, protein purification, and quantification. This application note provides a detailed protocol for assembling a gel casting station and preparing laboratory-grade polyacrylamide gels, ensuring reproducible and reliable results for protein electrophoresis research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Equipment

A properly configured gel casting station requires specific reagents and equipment. The following table details the essential materials, their functions, and critical specifications for preparing polyacrylamide gels.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Equipment for a Gel Casting Station

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glass Plates & Spacers | Forms the mold for the gel. | Clean thoroughly before use to ensure gel polymerizes evenly and does not detach [25]. |

| Casting Frame/Stand | Holds glass plates and spacers securely to prevent leaks. | Ensure no vaseline is needed and apparatus is correctly aligned to prevent leaking [25]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the polyacrylamide matrix for size-based separation. | Typically used at a 19:1 or 29:1 ratio; potent neurotoxin—wear appropriate PPE (gloves, mask) when handling powder [3]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiates the polymerization reaction as a catalyst. | Use fresh aliquots; old or improperly stored APS will cause slow or incomplete polymerization [3] [25]. |

| TEMED | Catalyzes polymerisation by generating free radicals. | Use fresh; quantity can be adjusted to control polymerization speed [25]. |

| Tris Buffer | Provides the required pH environment for gel polymerization and electrophoresis. | Common buffers are Tris-Glycine or Tris-HCl for SDS-PAGE. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge. | Ensure SDS is added to the sample buffer; absence will prevent proteins from migrating into the gel [25]. |

| Comb | Creates wells for sample loading. | Remove carefully after polymerization to avoid damaged or distorted wells, which lead to smeared bands [33] [25]. |

| Gel Stains | For visualizing proteins post-electrophoresis. | Options include Coomassie Blue, Silver Stain, or fluorescent dyes. For DNA, SYBR-safe or GelRed are non-mutagenic alternatives to ethidium bromide [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Assembling and Casting a Polyacrylamide Gel

Safety Precautions

- Acrylamide Handling: Acrylamide in its powdered form is a potent neurotoxin and can be easily aerosolized. Always wear a mask and gloves when weighing powdered acrylamide. Consider using pre-made liquid acrylamide solutions or pre-cast gels to minimize risk [3].

- General Practice: Wear gloves and lab coats throughout the procedure. Dispose of gel waste according to institutional safety guidelines.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Table 2: Step-by-Step Gel Casting Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assembly | Clean glass plates and spacers thoroughly. Assemble the plates with spacers and secure them in the casting frame. Ensure a tight seal to prevent leakage. | A leak-proof assembly is crucial. Check for gaps and ensure plates are correctly aligned [25]. |

| 2. Gel Solution Prep | Prepare the resolving gel solution according to the desired percentage (see Table 3). Mix all components except TEMED and APS. Degas the solution for 1-2 minutes to prevent bubble formation during polymerization. | Degassing improves polymerization consistency and minimizes air bubbles in the final gel. |

| 3. Polymerization Initiation | Add the required volumes of APS and TEMED to the degassed gel solution. Swirl gently to mix. Avoid introducing air bubbles. | Use fresh APS and TEMED. Incomplete polymerization can result from old reagents [3] [25]. |

| 4. Casting Resolving Gel | Pipette the resolving gel solution into the gap between the glass plates. Leave space for the stacking gel (approx. 1-2 cm below the comb teeth). | |

| 5. Overlaying | Gently overlay the resolving gel surface with water-saturated butanol or deionized water. This ensures a flat, even gel surface by excluding oxygen. | A flat interface between the stacking and resolving gels is critical for sharp band resolution [25]. |

| 6. Polymerization | Allow the gel to polymerize completely for 20-45 minutes at room temperature. Polymerization is indicated by a distinct schlieren line at the overlay-gel interface. | Do not disturb the gel during polymerization. Insufficient polymerization time can lead to poor well formation [25]. |

| 7. Casting Stacking Gel | Pour off the overlay liquid. Prepare the stacking gel solution (typically 3-5% acrylamide), add APS and TEMED, and pour it onto the polymerized resolving gel. | |

| 8. Inserting Comb | Immediately insert a clean, dry comb into the stacking gel solution. Avoid trapping air bubbles under the teeth of the comb. | Ensure the comb is level. Pushing the comb all the way to the bottom can cause sample leakage and smearing [33]. |

| 9. Final Polymerization | Allow the stacking gel to polymerize for 20-30 minutes. Once set, the gel can be used immediately or wrapped in moist paper towels, sealed in a plastic bag, and stored at 4°C for short-term use (1-2 days). | Remove the comb carefully and steadily to prevent damage to the wells [33]. |

Gel Percentage Selection Guide

The concentration of acrylamide in the resolving gel determines the pore size and thus the effective separation range for proteins of different molecular weights.

Table 3: Polyacrylamide Gel Concentrations for Optimal Protein Separation Adapted from general principles of nucleic acid and protein electrophoresis [3]

| % Acrylamide | Effective Separation Range (kDa) |

|---|---|

| 8% | 30 - 200 |

| 10% | 20 - 100 |

| 12% | 15 - 70 |

| 15% | 10 - 50 |

Note: For samples with a broad range of molecular weights or unknown sizes, a 4%-20% gradient gel is recommended for optimal resolution across sizes [25].

Workflow and Troubleshooting

The following workflow diagram outlines the entire process from setup to electrophoresis, highlighting key decision points and quality control checkpoints.

Troubleshooting Common Casting and Early Run Issues

Even with careful preparation, issues can arise. The table below lists common problems related to gel casting, their potential causes, and solutions.

Table 4: Troubleshooting Guide for Gel Casting and Initial Electrophoresis

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Gel does not polymerize | TEMED or APS left out; reagents too old; temperature too low. | Increase APS/TEMED; use fresh aliquots; cast gel at room temperature [25]. |

| Slow or incomplete polymerization | Old APS stored above -20°C. | Use fresh APS aliquots kept frozen [3] [25]. |

| Leaking during casting | Glass plates chipped or misaligned; casting frame not sealed. | Check plate integrity; reassemble apparatus correctly; use Vaseline on spacers if needed [25]. |

| Poorly formed or damaged wells | Comb removed too early or carelessly; stacking gel too concentrated. | Allow full polymerization (30 min); remove comb steadily and carefully; use lower % acrylamide for stacking gel [33] [25]. |

| Samples do not sink into wells | Insufficient glycerol in sample buffer; comb removed too early. | Ensure sample buffer has enough glycerol; let stacking gel polymerize fully before comb removal [25]. |

| Bands are skewed or distorted | Salt concentration in sample too high; polymerization around wells is poor; gel interface uneven. | Dialyze high-salt samples; ensure well-forming gel has enough APS/TEMED; overlay resolving gel carefully [25]. |

| Smeared bands | Protein overloaded; voltage too high; well damaged during loading. | Load 0.1–0.2 µg of protein per mm well width; decrease voltage; avoid puncturing wells with pipette tip [33] [34] [25]. |

A meticulously prepared gel casting station is the first critical step in obtaining publication-quality protein separation. By adhering to the detailed protocols for reagent preparation, gel casting, and assembly outlined in this document, researchers can ensure consistency, reproducibility, and high resolution in their SDS-PAGE experiments. Attention to detail—from using fresh chemical initiators to careful handling of combs and glass plates—will minimize analytical artifacts and streamline the path to reliable protein data, thereby strengthening the foundation of any subsequent research in drug development and proteomics.

This application note provides a detailed protocol for preparing the resolving gel in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), with emphasis on optimizing the critical steps of mixing, degassing, and pouring to achieve a flat polymerization interface. A flat gel interface is crucial for uniform protein migration and high-resolution separation, which are fundamental requirements for accurate analysis in protein research and drug development. The guidelines presented herein support reproducible and reliable gel preparation, enhancing data quality in electrophoretic experiments.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is a cornerstone technique for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. The quality of the electrophoresis results is profoundly dependent on the initial preparation of the polyacrylamide gel, particularly the resolving gel, which is responsible for separating proteins by size. The processes of mixing the gel solution, degassing to remove oxygen, and pouring the gel to achieve a flat interface are critical technical steps that directly impact polymerization quality, band sharpness, and overall separation performance [35] [36]. This protocol details these key steps within the context of preparing a standard SDS-polyacrylamide resolving gel, providing researchers with a standardized method to ensure reproducibility and optimal results.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their specific functions in the preparation of the resolving gel.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Resolving Gel Preparation

| Reagent | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer matrix that acts as a molecular sieve for separating proteins [37]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (e.g., 1.5 M, pH 8.8) | Provides the appropriate pH environment for efficient polymerization and protein separation in the resolving gel [36]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | An ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, allowing separation based primarily on molecular weight [37]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | A source of free radicals that initiates the polymerization reaction of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide [36] [38]. |

| TEMED (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine) | A catalyst that accelerates the polymerization process by decomposing APS to generate free radicals [36] [38]. |

| Water-saturated n-butanol or Isopropanol | Layered on top of the poured gel solution to exclude oxygen and ensure a flat, uniform polymerization interface [36]. |

Detailed Methodology

Mixing the Gel Solution

- Recipe Formulation: Calculate the required volumes of all components based on the desired gel percentage and number of gels. A typical resolving gel solution for two gels includes water, the appropriate Tris-HCl buffer (e.g., 1.5 M, pH 8.8), acrylamide/bis-acrylamide stock solution, and a 10% SDS solution [36].

- Combining Reagents: In a clean flask, first mix the water, Tris buffer, and acrylamide solution. Swirl the flask gently to combine. It is recommended to bring the gel solution to room temperature before proceeding, as cold solutions can hold more dissolved oxygen and polymerize more slowly after degassing [35].

- Pre-degassing Consideration: Ensure the solution is well-mixed and free of large air bubbles before the degassing step.

Degassing the Gel Solution

- Purpose: Degassing is a critical step to remove dissolved oxygen from the gel solution. Oxygen inhibits the polymerization process by reacting with the free radicals generated by APS and TEMED, which can lead to slow, uneven, or incomplete polymerization, resulting in poor gel quality and irreproducible separations [35].

- Procedure: Transfer the mixed gel solution to an Ehrlenmeyer flask to prevent boil-over. Place the flask on a house vacuum or aspirator for approximately 5-10 minutes. The solution may bubble vigorously as gas is removed.

- Key Considerations:

- Duration: For polymerization systems initiated primarily by APS and TEMED, a degassing time of 5-10 minutes is typically sufficient [35]. Avoid excessive degassing (e.g., beyond 10-15 minutes), which is unnecessary and can be detrimental if riboflavin is used as a co-initiator.

- Temperature: Degassing is more effective and faster if the solution is at room temperature (23–25°C) rather than cold [35].

Initiating Polymerization and Pouring

- Adding Polymerization Initiators: After degassing, swiftly add the required volumes of 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) and TEMED to the flask. Swirl the flask gently but thoroughly to ensure homogeneous mixing. Note: The addition of TEMED and APS will begin the polymerization process immediately; work efficiently from this point.

- Pouring the Gel: Using a pipette or by carefully pouring, transfer the gel solution between the assembled glass plates. Pour the solution to a level approximately 1 cm below where the bottom of the comb will be seated [36].

- Achieving a Flat Interface: Immediately after pouring, gently layer a volume of water-saturated n-butanol or isopropanol on top of the gel solution. This step is crucial as it excludes ambient oxygen from the surface of the gel solution, which would otherwise inhibit polymerization and create a curved, uneven interface [36].

- Polymerization: Allow the gel to polymerize undisturbed at room temperature. Polymerization is typically complete within 20-30 minutes, indicated by a distinct refractive line forming between the polymerized gel and the overlaying alcohol solution. The gel is now ready for the next steps, including pouring the stacking gel.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the key steps involved in preparing the resolving gel, from mixing to the completed polymerization.

Diagram 1: Workflow for preparing the resolving gel, highlighting the critical path from mixing to polymerization.

Data Presentation: Troubleshooting Common Issues

Even with a standardized protocol, issues can arise. The following table outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Resolving Gel Preparation

| Observation | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Slow or incomplete polymerization | Insufficient degassing, leaving oxygen to inhibit the reaction [35]. | Ensure proper vacuum is applied during degassing and that the solution is at room temperature. |

| Old or inactive APS/TEMED [36]. | Prepare fresh APS solution and ensure reagents are stored properly. | |

| Curved or uneven gel interface | Failure to layer with alcohol after pouring [36]. | Always layer the gel solution with water-saturated n-butanol or isopropanol immediately after pouring. |

| Uneven sealing of the gel plates, leading to leaks. | Ensure gel plates are properly sealed with agarose or other suitable sealant before pouring [36]. | |

| Smeared protein bands | Gel polymerization at too high a temperature, causing uneven gel structure [39]. | Polymerize and run gels at a consistent, cool temperature (e.g., in a cold room or with a cooling apparatus). |

| Bubbles trapped in the polymerized gel | Failure to remove bubbles after pouring the gel solution. | Push bubbles away from the well comb or towards the edges with a pipette tip after pouring [40]. |

Discussion

The consistent preparation of a high-quality resolving gel is a foundational skill in protein biochemistry. The practice of degassing, while sometimes omitted in rushed protocols, is scientifically justified. Oxygen is a potent free radical trap that directly competes with the acrylamide polymerization reaction, leading to inconsistent pore sizes and potential gel artifacts [35]. Furthermore, achieving a flat interface via alcohol layering is a simple yet effective method to ensure that proteins in all lanes of the gel enter the resolving region simultaneously, which is a prerequisite for accurate molecular weight determination and comparative quantification.

For specialized applications, alternative polymerization methods exist. For instance, photopolymerization using riboflavin can be employed, which is compatible with a wider range of pH conditions and is non-oxidative [41]. However, it requires careful optimization of degassing time, as a small amount of oxygen is necessary for the conversion of riboflavin to its active form [35].

This application note provides a robust, step-by-step protocol for preparing a polyacrylamide resolving gel, with a focused examination of the critical steps that ensure a flat, uniform gel interface. By meticulously following the procedures for mixing, degassing, and pouring outlined herein, researchers can significantly improve the reproducibility and resolution of their protein separations, thereby enhancing the reliability of data generated in downstream analyses for research and drug development.

In the preparation of polyacrylamide gels for protein electrophoresis, achieving a uniform, flat polymerizing surface is critical for high-resolution separation. The isopropanol overlay technique is a standard laboratory practice used to create an oxygen-free and level barrier over the gel solution during the crucial polymerization period. This protocol details the application of isopropanol overlays within the context of SDS-PAGE, providing researchers with a definitive guide to improving gel quality and reproducibility for protein research and drug development.

The Principle of the Isopropanol Overlay

The Challenge of Oxygen Inhibition

The polymerization of acrylamide into a polyacrylamide gel is a free-radical chain reaction catalyzed by tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED) and initiated by ammonium persulfate (APS) [2]. Molecular oxygen (O~2~) acts as a potent inhibitor of this process by reacting with the initiating and propagating free radicals, thereby terminating the polymerization chain reaction [42] [2]. This inhibition can lead to several artifacts:

- Uneven Polymerization: A slanted or wavy gel surface that compromises lane-to-lane running consistency.

- Poor Resolution: Incomplete polymerization results in a gel with inconsistent pore size, leading to diffuse protein bands and unreliable molecular weight determination [2].

- Extended Polymerization Time: Significant oxygen exposure can delay or entirely prevent gel formation.

The Isopropanol Solution

To mitigate the effects of oxygen, an inert, water-miscible, and denser-than-air liquid is layered on top of the freshly poured gel solution. Isopropanol (IPA) is the solvent of choice for this overlay due to its ideal physicochemical properties [42]:

- Water Miscibility: Allows for easy removal and clean interface formation.

- Inert Nature: Does not interfere with the free-radical polymerization chemistry.

- Low Density and Volatility: Ensures it sits atop the aqueous gel solution and evaporates cleanly after its function is served.