SDS in PAGE: The Definitive Guide to Denaturation, Separation, and Analysis for Life Science Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the role of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) in Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE), a cornerstone technique in biochemistry and molecular biology.

SDS in PAGE: The Definitive Guide to Denaturation, Separation, and Analysis for Life Science Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the role of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) in Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE), a cornerstone technique in biochemistry and molecular biology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles to advanced applications. It covers the mechanism by which SDS denatures proteins and confers uniform charge, the standard SDS-PAGE protocol and its critical steps, common troubleshooting scenarios for poor band resolution, and a comparative analysis with alternative electrophoretic methods like Native PAGE and BN-PAGE. The article also explores innovative adaptations, such as NSDS-PAGE, that preserve protein function, highlighting the technique's evolving role in proteomics and diagnostic research.

SDS Unmasked: How a Simple Detergent Enables Pure Size-Based Protein Separation

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is an anionic detergent that serves a critical function in molecular biology by denaturing proteins and conferring upon them a uniform negative charge. This foundational process enables the separation of complex protein mixtures by molecular weight via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). This technical guide explores the chemical properties and mechanisms of SDS, detailing its indispensable role in protein analysis. Framed within the context of proteomic research and drug development, we provide detailed methodologies, quantitative data on SDS-protein interactions, and essential resource guidance for research implementation, underscoring how SDS-PAGE remains a cornerstone technique for protein characterization, purity assessment, and diagnostic applications.

In the realm of protein biochemistry, the ability to separate, visualize, and analyze proteins based on molecular weight is a fundamental requirement. SDS-PAGE fulfills this need, and its efficacy hinges almost entirely on the properties of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). This anionic surfactant is integral to the technique's name and function [1]. The primary objective of SDS-PAGE is to separate proteins solely on the basis of their molecular weight, eliminating confounding variables such as innate protein charge or three-dimensional shape [2]. SDS achieves this through a dual mechanism: it efficiently denatures protein structures, unfolding them into linear polypeptides, and simultaneously coats them with a uniform negative charge [3] [4]. This process ensures that when an electric field is applied, all proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix toward the anode at a rate inversely proportional to their size [5]. The critical role of SDS extends across basic research, clinical diagnostics, and biopharmaceutical development, making a thorough understanding of its action essential for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Chemical Identity and Core Properties of SDS

SDS is a key member of the alkyl sulfate family of anionic detergents. Its amphipathic nature is defined by a distinct hydrophobic "tail", a 12-carbon alkyl chain (dodecyl), and a hydrophilic "head", the sulfate group [1] [4]. This structure is the source of its protein-denaturing power and its effectiveness as a surfactant.

In aqueous solutions, SDS molecules exhibit critical aggregation behavior. Below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 7 to 10 millimolar, SDS exists predominantly as monomers. However, above the CMC, SDS monomers self-assemble into spherical micelles, with each micelle consisting of approximately 62 SDS molecules [6]. It is crucial to note that only the SDS monomers are responsible for binding to and denaturing proteins, while the micelles remain in solution and do not adsorb proteins [6].

Table 1: Fundamental Physicochemical Properties of SDS

| Property | Description | Significance in Protein Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Name | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate | Anionic detergent used for protein denaturation [6]. |

| Molecular Structure | Amphipathic: 12-carbon hydrophobic tail, anionic sulfate head group [1]. | Tail disrupts hydrophobic protein core; head confers charge [1]. |

| Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | 7-10 mM [6] | Monomers below CMC denature proteins; micelles form above this concentration [6]. |

| Micelle Structure | ~62 molecules per spherical micelle [6] | Micelles do not bind protein backbones but are part of the electrophoretic system [6]. |

The hydrophobic tail readily interacts with nonpolar regions of proteins, while the ionic sulfate group disrupts electrostatic interactions and provides a strong negative charge. This combination is the foundation for SDS's potent denaturing capability and its ability to mask a protein's intrinsic charge [1].

The Dual Mechanism of SDS Action

SDS exerts its effect on proteins through two synergistic mechanisms that are essential for successful electrophoretic separation.

Protein Denaturation and Unfolding

SDS fundamentally disrupts the native structure of proteins. Its hydrophobic region interacts with and embeds into the hydrophobic core of the protein, while its ionic part disrupts salt bridges and other non-covalent interactions that stabilize secondary and tertiary structures [1]. This results in the loss of a protein's higher-order structures—unfolding it into a random coil or rigid rod-like conformation [4]. For complete denaturation, SDS treatment is typically combined with heat (95°C for several minutes) to break hydrogen bonds, and reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol (BME) or dithiothreitol (DTT) to cleave disulfide bonds, thereby linearizing the polypeptide into its primary structure [1].

Charge Conferment and Masking

Following denaturation, SDS binds to the unfolded protein backbone at a nearly constant weight ratio of 1.4 grams of SDS per 1 gram of protein [6] [3]. This corresponds to approximately one SDS molecule for every two amino acid residues [6]. This saturation binding coats the entire polypeptide in a uniform layer of negative charge. The intrinsic charge of the amino acids becomes negligible compared to the overwhelming negative charge provided by the bound SDS [6] [2]. Consequently, all SDS-protein complexes possess a similar net negative charge and a nearly identical charge-to-mass ratio, ensuring that during electrophoresis, separation is based solely on molecular size and not on the protein's original charge or shape [3] [1].

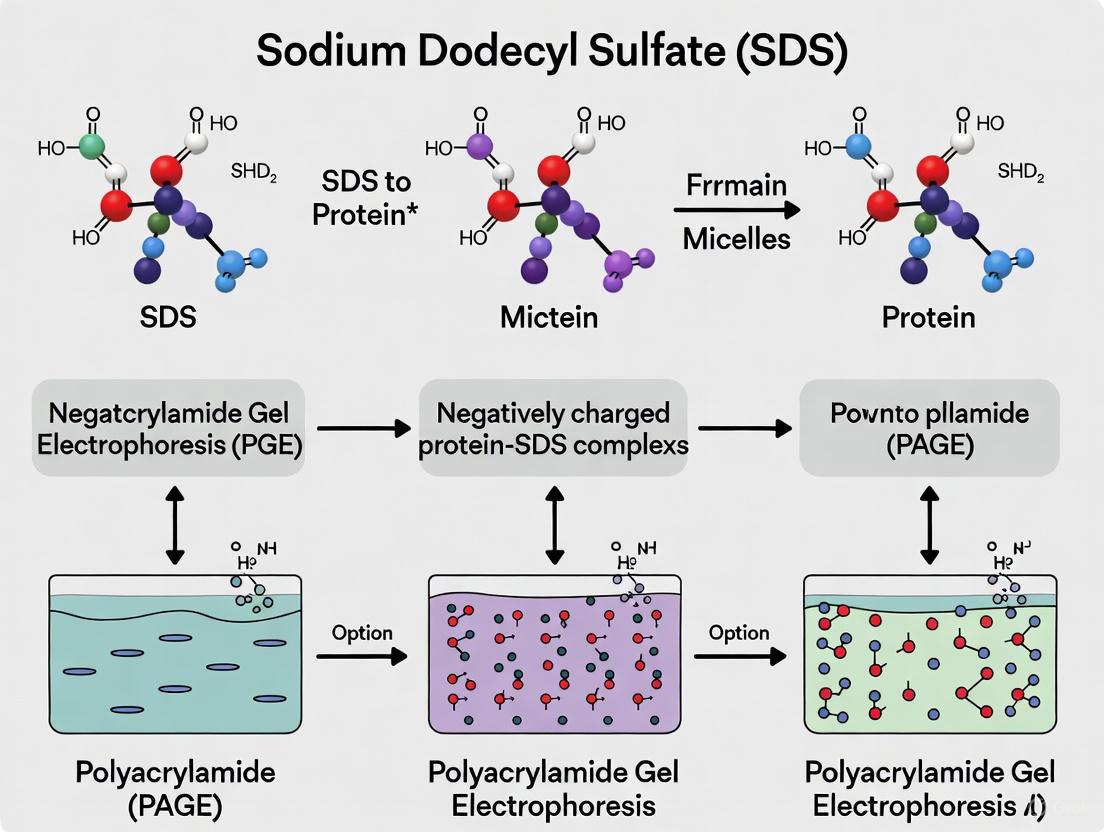

Diagram 1: SDS-Mediated Protein Denaturation and Linearization Pathway

SDS-PAGE: Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The following section outlines a standard protocol for SDS-PAGE, highlighting the critical role of SDS at each stage. This procedure is adaptable for both mini-gel (8 x 8 cm) and larger formats [2].

Sample Preparation

- Lysate Preparation: Solubilize proteins from whole tissue or cell culture using mechanical homogenization (e.g., blender, sonicator) in a lysis buffer containing detergents and protease inhibitors [7].

- Protein Quantification: Determine the protein concentration of the lysate using a standard assay (e.g., BCA, Bradford).

- Denaturation: Mix the protein sample with an SDS-based sample buffer (Laemmli buffer). A typical buffer contains:

- Heat Denaturation: Heat the sample-protein buffer mixture at 95°C for 3-5 minutes (or 70°C for 10 minutes) to complete the denaturation process [5] [7]. Cool briefly and centrifuge before loading.

Gel Casting and the Discontinuous System

SDS-PAGE employs a discontinuous buffer system using two distinct gel layers to achieve high-resolution separation [4].

- Resolving Gel (Separating Gel): This lower gel is poured first. It typically has a higher acrylamide concentration (8-15%, depending on target protein size) and a pH of 8.8. This gel is responsible for the size-based separation of proteins [5] [1].

- Stacking Gel: This upper gel is poured after the resolving gel has polymerized. It has a lower acrylamide concentration (4-5%) and a pH of 6.8. Its function is to concentrate all protein samples into a sharp, unified band before they enter the resolving gel, resulting in tighter, clearer bands [1] [4].

The polymerization of both gels is catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED, which generate free radicals to initiate the cross-linking of acrylamide and bisacrylamide monomers [1].

Electrophoresis and the Role of Buffers

- Assembly: Place the cast gel cassette into the electrophoresis chamber and fill the upper and lower chambers with running buffer.

- Running Buffer Composition: The standard running buffer contains Tris, glycine, and SDS at pH 8.3 [4]. The SDS in the running buffer helps maintain the denatured state of the proteins during their migration.

- Loading and Run: Load prepared samples and a molecular weight marker into the wells. Apply a constant voltage (100-200V). The stacking effect occurs as the glycine in the running buffer (pH 8.3) enters the stacking gel (pH 6.8), becoming a zwitterion with low mobility, creating a voltage gradient that "stacks" proteins into a sharp line [4]. Once the stacked proteins enter the resolving gel (pH 8.8), the glycine becomes fully negatively charged and migrates faster, leaving the proteins to be separated by size in the resolving gel matrix.

Table 2: Quantitative Guide to Polyacrylamide Gel Concentration

| Target Protein Size (kDa) | Recommended Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Purpose and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| < 25 | 15% | High percentage for optimal resolution of small proteins/peptides [7]. |

| 25 - 50 | 12% | Standard concentration for medium-sized proteins [7]. |

| 50 - 100 | 10% | Standard concentration for many common proteins [7]. |

| > 100 | 8% | Low percentage for large proteins to facilitate migration [7]. |

| Broad Range | 4-20% (Gradient) | A single gel that can resolve a wide spectrum of protein sizes [3]. |

Advanced Research Context: NSDS-PAGE and Functional Retention

While traditional SDS-PAGE is a powerful denaturing tool, a modified method known as Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) has been developed for applications where retaining protein function or non-covalently bound cofactors (like metal ions) is desirable [8]. This technique addresses a key shortcoming of standard SDS-PAGE, which destroys functional properties [8].

The NSDS-PAGE protocol involves significant modifications:

- Sample Buffer: Removal of SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer and omission of the heating step [8].

- Running Buffer: Reduction of SDS concentration in the running buffer from the standard 0.1% to 0.0375%, along with the deletion of EDTA [8].

These milder conditions have been shown to dramatically increase the retention of bound metal ions in proteomic samples from 26% to 98% and preserve the enzymatic activity of most model enzymes tested, while still maintaining high-resolution separation [8]. This demonstrates that the role of SDS in electrophoresis can be precisely modulated to serve broader research goals, particularly in metallomics and functional proteomics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent / Solution | Core Function | Technical Specification / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge [1] [4]. | Typically used at 1-2% in sample buffer; binds 1.4g per 1g protein [6] [3]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME) | Cleaves disulfide bonds to fully linearize proteins [1]. | DTT (10-100 mM) or BME (5% v/v) are common; DTT is less odorous [6] [1]. |

| Acrylamide / Bis-Acrylamide | Forms the porous gel matrix for molecular sieving [3]. | Total concentration (e.g., 8-15%) and crosslinker ratio determine pore size [3] [1]. |

| APS & TEMED | Catalyzes the polymerization of the polyacrylamide gel [1]. | APS provides free radicals; TEMED accelerates polymerization [1]. |

| Tris-Based Buffers | Provides controlled pH environment for gel polymerization and electrophoresis [4]. | Discontinuous system: Stacking gel (pH ~6.8), Resolving gel (pH ~8.8), Running buffer (pH ~8.3) [4]. |

| Glycine | Key ion in discontinuous buffer system for protein stacking [4]. | In running buffer (pH 8.3); charge state changes at different gel pHs to enable stacking [4]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Allows estimation of protein size from migration distance [2]. | Pre-stained or unstained protein ladders with known molecular weights [2]. |

| N-(4-bromophenyl)-4-nitroaniline | N-(4-Bromophenyl)-4-nitroaniline CAS 40932-71-6 | |

| 1-(5-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)propan-2-amine | 1-(5-methyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)propan-2-amine, CAS:1025087-55-1, MF:C7H13N3, MW:139.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate is far more than a simple detergent; it is the fundamental component that enables robust, reproducible protein separation by molecular weight. Its dual action of denaturing proteins and masking their intrinsic charge is a masterpiece of biochemical application, simplifying complex protein mixtures into a parameter that can be easily analyzed. From its foundational role in the standard SDS-PAGE protocol to more nuanced applications like NSDS-PAGE, SDS continues to be an indispensable tool. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep and mechanistic understanding of SDS is not merely academic—it is a practical necessity for designing experiments, interpreting electrophoretograms, and advancing our knowledge of the proteome in health and disease. As protein-based therapeutics and diagnostics continue to grow, the role of SDS-PAGE, and by extension SDS, remains secure as a cornerstone of modern biochemical analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as a cornerstone technique in molecular biology and biochemistry, enabling researchers to separate proteins based primarily on their molecular weight [6]. The revolutionary development of this method by Ulrich Laemmli in 1970 incorporated SDS to largely eliminate the influences of protein structure and inherent charge, allowing separation based predominantly on polypeptide chain length [5] [9]. This technique has become indispensable in modern laboratories, with applications spanning from basic protein characterization to quality control in biopharmaceutical development [10] [11].

The fundamental breakthrough of SDS-PAGE lies in its use of SDS to execute a dual-action mechanism on proteins. This mechanism ensures that proteins unfold into linear chains and acquire a uniform negative charge distribution, effectively standardizing their behavior during electrophoresis [5] [6]. By masking intrinsic charge differences and eliminating the effects of complex three-dimensional structures, SDS allows researchers to determine molecular weight with reasonable accuracy, assess sample purity, and prepare samples for downstream applications like western blotting [9]. Understanding this dual-action mechanism is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on this technique for accurate protein analysis.

The Molecular Mechanism of SDS Action

Protein Linearization and Denaturation

The first critical action of SDS involves the systematic denaturation of proteins into their linear form. SDS is a potent anionic detergent with strong protein-denaturing properties [5]. When proteins are treated with SDS, particularly at concentrations above 1 mM, the detergent disrupts nearly all non-covalent bonds that maintain the protein's secondary and tertiary structure, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions [6] [9]. This disruption occurs as the hydrophobic tail of SDS inserts into the protein core, while the hydrophilic sulfate head group remains exposed to the aqueous environment.

This denaturation process unfolds the native three-dimensional structure of proteins, converting them into random coil conformations [12]. The resulting SDS-protein complexes adopt a rod-like shape with a consistent charge-to-mass ratio, effectively eliminating differences in molecular shape as a factor in electrophoretic separation [6]. For complete denaturation, samples are typically heated to 95°C for several minutes in the presence of SDS and reducing agents like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), which cleave disulfide bonds that covalently stabilize protein structures [6] [13]. This comprehensive linearization ensures that protein migration depends solely on molecular dimensions rather than structural complexities.

Negative Charge Shielding and Charge Masking

The second crucial action of SDS involves imparting a uniform negative charge to all proteins. SDS binds to the protein backbone at an approximately constant ratio of 1.4 grams of SDS per gram of protein [6] [13]. This binding ratio corresponds to approximately one SDS molecule for every two amino acid residues, creating a nearly continuous "shield" of negative charges along the entire polypeptide chain [6].

This extensive binding masks the proteins' intrinsic charges, whether positive or negative, effectively overwhelming them with the negative charges from SDS [9] [12]. Consequently, all proteins acquire a similar net negative charge density, standardizing their charge-to-mass ratios [6]. During electrophoresis, this charge uniformity ensures that all proteins migrate toward the anode (positive electrode) at rates determined primarily by their size rather than their inherent charge characteristics [5]. This charge masking represents a fundamental aspect of the SDS-PAGE technique, enabling molecular weight estimation with an error margin typically around ±10% [6].

Figure 1: Dual-Action Mechanism of SDS in Protein Denaturation and Charge Shielding

Quantitative Aspects of SDS-Protein Interactions

The effectiveness of SDS-PAGE relies on precise quantitative relationships between SDS and proteins. Understanding these parameters is essential for optimizing experimental conditions and interpreting results accurately.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in SDS-PAGE

| Parameter | Value/Range | Functional Significance | Experimental Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS Binding Ratio | 1.4 g SDS / 1 g protein [6] [13] | Ensures complete charge masking | Critical for accurate molecular weight determination |

| SDS Monomer Concentration | > 1 mM for protein denaturation [6] | Maintains denaturing conditions | Prevents protein refolding during electrophoresis |

| Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | 7-10 mM in aqueous solutions [6] | Determines SDS monomer availability | Ensures sufficient SDS for protein binding |

| Typical SDS in Running Buffer | 0.1% (standard) [6] to 0.0375% (native SDS-PAGE) [8] | Maintains protein linearity during separation | Affects resolution and protein stability |

| Optimal Sample Heating | 95°C for 3-5 minutes [5] [6] | Ensures complete denaturation | Incomplete heating causes smearing |

The binding interaction between SDS and proteins exhibits some variability depending on protein characteristics. Hydrophobic proteins may bind more SDS, while proteins with post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and glycosylation may bind less SDS [12]. These variations, though generally minimal, can occasionally cause anomalous migration and should be considered when proteins run at unexpected molecular weights [12]. Additionally, the presence of SDS micelles in solutions above the critical micellar concentration provides a reservoir of SDS monomers for sustained protein binding throughout the electrophoresis process [6].

Experimental Protocols for SDS-PAGE

Sample Preparation Methodology

Proper sample preparation is crucial for successful SDS-PAGE separation. The following protocol ensures complete protein denaturation and linearization:

Sample Buffer Preparation: Prepare 2× Laemmli buffer containing 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), and 10% β-mercaptoethanol (added fresh) or 10-100 mM DTT as reducing agent [13] [12].

Sample Denaturation: Mix protein sample with an equal volume of 2× sample buffer. Heat the mixture at 95°C for 3-5 minutes in a heat block or boiling water bath [5] [6]. For heat-sensitive proteins, alternative denaturation at 70°C for 10 minutes may be used [6].

Centrifugation: Briefly centrifuge the denatured samples at 15,000 rpm for 1 minute to collect condensation and ensure the entire sample is at the bottom of the tube [5].

Loading: Load 20-50 μg of protein per well for Coomassie staining or 1-10 μg for silver staining [13]. Include appropriate molecular weight markers in a separate well.

This protocol ensures complete protein denaturation, reduction of disulfide bonds, and proper charge masking. The glycerol in the buffer adds density to facilitate loading, while bromophenol blue serves as a tracking dye to monitor electrophoresis progress [12].

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis Conditions

The discontinuous gel system fundamental to SDS-PAGE consists of two distinct layers with different pore sizes and pH values:

Table 2: Standard Gel Compositions for SDS-PAGE

| Component | Stacking Gel (pH 6.8) | Separating Gel (pH 8.8) | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide | 4-5% [6] [13] | 6-15% (depending on target protein size) [5] [9] | Creates porous matrix for separation |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | 0.5-1.0 M, pH 6.8 [13] | 1.5 M, pH 8.8 [13] | Maintains appropriate pH for stacking and separation |

| SDS | 0.1% [13] | 0.1% [13] | Maintains protein denaturation |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 0.05% [13] | 0.05% [13] | Polymerization initiator |

| TEMED | 0.1% [13] | 0.1% [13] | Polymerization catalyst |

| Glycerol | - | - | Adds density for loading |

Electrophoresis Protocol:

Gel Casting: Assemble glass plates with spacers. Prepare separating gel solution, pour between plates, and overlay with water-saturated isopropanol or water to prevent oxygen inhibition of polymerization. Allow to polymerize for 20-30 minutes. Pour stacking gel solution over polymerized separating gel and insert combs. Polymerize for 15-20 minutes [5] [13].

Electrophoresis Setup: Mount gel in electrophoresis apparatus filled with running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [13]. Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers into wells.

Electrophoresis Run: Apply constant voltage of 80V until dye front enters separating gel, then increase to 100-150V until dye front reaches bottom of gel [13] [9]. Cooling the apparatus with an ice bath or circulating water cooler is recommended for high-voltage runs to prevent heat-induced artifacts [13].

The discontinuous buffer system creates a stacking effect at the interface between the stacking and separating gels, concentrating protein samples into sharp bands before separation, thereby significantly enhancing resolution [6] [12].

Figure 2: SDS-PAGE Experimental Workflow from Sample Preparation to Analysis

Advanced Applications and Modifications

Native SDS-PAGE for Functional Analysis

A significant modification of the standard technique, termed Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), has been developed to address the limitation of complete protein denaturation [8]. This method reduces SDS concentration in the running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375% and eliminates both EDTA from sample buffers and the heating step [8]. These modifications result in retention of Zn²⺠bound in proteomic samples increasing from 26% to 98% compared to standard SDS-PAGE, with seven of nine model enzymes maintaining activity after separation [8].

This approach bridges the gap between the high resolution of traditional SDS-PAGE and the functional preservation of native electrophoresis methods like Blue-Native PAGE [8]. NSDS-PAGE is particularly valuable for metalloprotein analysis, enzyme activity studies, and investigations of protein complexes that maintain stability in mild detergent conditions [8].

Capillary Electrophoresis as an Advanced Alternative

Capillary electrophoresis SDS (CE-SDS) represents a technological evolution from traditional slab gel SDS-PAGE [11]. This automated approach provides several advantages, including higher resolution, superior reproducibility, quantitative precision, reduced analysis time, and elimination of manual gel casting [11]. The method uses narrow-bore capillaries filled with separation matrix, with detection via UV absorption or fluorescence, enabling accurate quantification without staining procedures [11].

CE-SDS has been widely adopted in biopharmaceutical industries for characterization of therapeutic proteins, including monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and fusion proteins, where quantitative analysis and regulatory compliance are essential [11]. The method maintains the fundamental SDS-mediated separation principles while offering enhanced precision and automation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SDS-PAGE Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technical Specifications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Protein denaturation and charge masking | >99% purity; 10-20% stock solution in water | Critical for consistent results; filter stock solutions |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Gel matrix formation | Typically 29:1 or 37.5:1 ratio of acrylamide to bis-acrylamide | Neurotoxin - handle with gloves in fume hood |

| TEMED | Gel polymerization catalyst | >99% purity; store at 4°C | Accelerates polymerization; add just before casting |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Gel polymerization initiator | 10% solution in water; prepare fresh weekly | Degrades with time; affects polymerization efficiency |

| Tris Buffer | pH maintenance | 1.0 M, pH 6.8 (stacking gel); 1.5 M, pH 8.8 (separating gel) | Essential for discontinuous buffer system |

| Glycine | Running buffer component | Electrophoresis grade; running buffer: 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS | Zwitterionic properties enable stacking effect |

| DTT or β-mercaptoethanol | Disulfide bond reduction | DTT: 10-100 mM; β-mercaptoethanol: 5% by volume | Essential for complete unfolding of proteins with disulfide bonds |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Size calibration | Pre-stained or unstained; cover expected size range | Include in every gel for accurate molecular weight determination |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | Protein staining | 0.1% in 40% ethanol, 10% acetic acid | Standard sensitivity; compatible with mass spectrometry |

| 4-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2,5-dimethylthiazole | 4-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2,5-dimethylthiazole|High Purity | Get 4-(4-Chlorophenyl)-2,5-dimethylthiazole for research. This thiazole derivative is used in medicinal chemistry and material science. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| H-Leu-Ala-Pro-OH | H-Leu-Ala-Pro-OH Tripeptide | H-Leu-Ala-Pro-OH is a synthetic tripeptide for research use. This product is For Research Use Only and not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. | Bench Chemicals |

The selection and quality of reagents directly impact the success and reproducibility of SDS-PAGE experiments. High-purity SDS is particularly critical as impurities can affect binding consistency and migration patterns. Similarly, fresh preparation of reducing agents ensures complete disruption of disulfide bonds. Commercial pre-cast gel systems provide convenience and consistency, particularly for standardized applications, while hand-cast gels offer flexibility in acrylamide concentrations and formulations for specialized separations [10].

The dual-action mechanism of SDS - protein linearization and negative charge shielding - remains fundamental to the widespread utility of SDS-PAGE in protein research. By systematically unfolding complex three-dimensional structures and masking intrinsic charge variations, SDS enables separation based primarily on molecular weight, providing researchers with a robust analytical tool. While modifications like Native SDS-PAGE and technological advancements like CE-SDS have expanded the applications and precision of SDS-based separations, the core mechanism established decades ago continues to underpin this essential methodology.

For drug development professionals and research scientists, understanding these mechanistic principles allows for proper experimental design, accurate interpretation of results, and troubleshooting when anomalies occur. As protein therapeutics and proteomics continue to advance, the principles of SDS-mediated separation maintain their relevance, ensuring this technique remains a cornerstone of biochemical analysis for the foreseeable future.

In the realm of proteomics and drug development, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as a cornerstone technique for protein analysis. The fundamental breakthrough of this method lies in its ability to separate proteins almost exclusively based on their molecular weight, a feat achieved by manipulating the inherent properties of proteins through a simple yet powerful detergent [2]. For researchers and pharmaceutical professionals tasked with characterizing complex protein mixtures, from enzyme therapeutics to monoclonal antibodies, this technique provides the reproducible, high-resolution data essential for quality control and diagnostic applications [14] [15]. This technical guide explores the core principle of achieving a uniform charge-to-mass ratio, a concept that has made SDS-PAGE an indispensable tool in life science research for over half a century [10].

The Fundamental Principle: From Native Structure to Linearized Chains

In their native state, proteins exhibit complex three-dimensional structures with charges determined by their amino acid composition, leading to variations in both net charge and molecular shape [16]. When an electric field is applied to these native proteins, their migration rate depends on a combination of charge, size, and shape, preventing separation based solely on molecular weight [2].

The key innovation of SDS-PAGE is the use of the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to eliminate these variables. The sample preparation process involves three critical steps that transform native proteins into a uniform state [16]:

- Denaturation: SDS disrupts hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds, destroying the protein's secondary and tertiary structure.

- Reduction: Adding a reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol cleaves disulfide bonds, separating protein subunits.

- Binding: SDS binds to the denatured protein backbone at a nearly constant ratio of 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein [17].

This process results in the formation of SDS-polypeptide complexes that adopt a rod-like shape with a length proportional to the protein's molecular weight [16] [17]. Most importantly, the intrinsic charge of the polypeptide becomes insignificant compared to the overwhelming negative charge provided by the bound SDS molecules, resulting in complexes that all possess a uniform negative charge density [2] [16].

Table 1: Key Steps in Protein Denaturation for SDS-PAGE

| Step | Reagents | Primary Function | Resulting Protein State |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturation | SDS, Heat (70-100°C) | Disrupts non-covalent interactions | Unfolded polypeptide chain |

| Reduction | DTT or β-mercaptoethanol | Cleaves disulfide bridges | Separate polypeptide subunits |

| Charge Masking | Excess SDS | Coats polypeptide backbone | Linear complex with uniform negative charge |

The Gel Matrix: A Molecular Sieve for Separation

The polyacrylamide gel serves as a molecular sieve that imposes a frictional force on the migrating proteins [5] [16]. This matrix consists of cross-linked acrylamide polymers whose pore size can be precisely controlled by varying the concentrations of acrylamide and bisacrylamide [2].

The separation occurs because smaller proteins navigate the porous network more easily than larger proteins, causing them to migrate faster through the gel [5]. This differential migration rate, combined with the uniform charge-to-mass ratio of all proteins, enables separation based primarily on polypeptide chain length [5] [16].

Table 2: Polyacrylamide Gel Concentrations and Optimal Separation Ranges

| Acrylamide Concentration (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| 7% | 50 - 500 | Large proteins |

| 10% | 20 - 300 | Standard protein mixture |

| 12% | 10 - 200 | Standard protein mixture |

| 15% | 3 - 100 | Small proteins and peptides |

For separating proteins of vastly different sizes or those with similar molecular weights, gradient gels with increasing acrylamide concentration (e.g., 4-20%) provide enhanced resolution across a broader molecular weight range [2].

The Discontinuous Buffer System: Focusing the Sample

A crucial innovation in standard SDS-PAGE is the use of a discontinuous buffer system (often called the Laemmli system), which incorporates both a stacking gel and a resolving gel [16]. This system ensures that all proteins enter the resolving gel simultaneously as sharp, focused bands, significantly improving resolution.

The process relies on controlling the charge states of ions in the buffer system, particularly glycine, which exists in different charge states depending on pH [16]. The diagram below illustrates this focusing mechanism and the subsequent separation.

Diagram 1: Protein stacking and separation in SDS-PAGE.

The separation of Clâ» ions from the Tris counter-ion creates a narrow zone with a steep voltage gradient that pulls the glycine ions along behind it, resulting in two narrowly separated fronts of migrating ions [16]. All proteins in the sample have an electrophoretic mobility intermediate between the extreme mobility of the glycine and Clâ», so when these fronts sweep through the sample well, the proteins are concentrated into a narrow zone between them [16]. This procession continues until it hits the running gel, where the pH switches to 8.8, causing glycine molecules to become mostly negatively charged and migrate faster than the proteins, leaving them to separate based on size in the resolving gel [16].

Experimental Protocol: Standard SDS-PAGE Methodology

Sample Preparation and Gel Casting

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for performing standard SDS-PAGE, adapted from multiple technical sources [5] [2]:

Materials Needed:

- Protein samples

- SDS-PAGE sample buffer (containing SDS, reducing agent, glycerol, and tracking dye)

- Precast or self-cast polyacrylamide gels

- Electrophoresis apparatus and power supply

- Running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer)

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

Gel Preparation:

- Use precast gels or prepare resolving gel by mixing acrylamide/bisacrylamide solution, Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.8), SDS, ammonium persulfate (APS), and TEMED [2].

- Pour resolving gel and overlay with water or alcohol to prevent oxygen inhibition of polymerization.

- After polymerization (20-30 minutes), prepare and pour stacking gel (lower acrylamide concentration, Tris-HCl pH 6.8) and insert combs [5].

Electrophoresis:

- Assemble gel cassette in electrophoresis chamber filled with running buffer.

- Load prepared samples and molecular weight markers into wells.

- Apply constant voltage (typically 150-200V) for approximately 45 minutes or until dye front reaches bottom [5].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Dismantle apparatus and carefully remove gel from plates.

- Proceed with protein detection methods such as Coomassie Blue staining, silver staining, or western blotting [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| SDS Sample Buffer | Tris-HCl, SDS, Glycerol, Bromophenol Blue, Reducing Agent | Denatures proteins, provides density for loading, and tracking dye |

| Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine with 0.1% SDS | Conducts current and maintains SDS coating during electrophoresis |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Acrylamide-Bisacrylamide matrix polymerized with APS/TEMED | Forms molecular sieve for protein separation based on size |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Pre-stained or unstained protein standards of known mass | Provides reference for estimating sample protein molecular weights |

| Stacking Gel | Low-concentration acrylamide (4-5%) at pH 6.8 | Concentrates protein samples into sharp bands before separation |

| Methanesulfonamide, N-(trimethylsilyl)- | Methanesulfonamide, N-(trimethylsilyl)-, CAS:999-96-2, MF:C4H13NO2SSi, MW:167.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Chloro-4-fluoro-3'-iodobenzophenone | 3-Chloro-4-fluoro-3'-iodobenzophenone, CAS:951890-19-0, MF:C13H7ClFIO, MW:360.55 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Recent Innovations

Native SDS-PAGE: Preserving Functional Properties

A significant innovation in electrophoretic techniques is Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), which modifies standard conditions to preserve certain functional properties of proteins while maintaining high resolution [8]. This method eliminates SDS and EDTA from the sample buffer, omits the heating step, and reduces SDS concentration in the running buffer (e.g., to 0.0375%) [8]. These modifications dramatically increase the retention of bound metal ions in metalloproteins from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% in NSDS-PAGE, with seven of nine model enzymes retaining activity after separation [8]. This advancement bridges the gap between the high resolution of denaturing SDS-PAGE and the functional preservation of native-PAGE, opening new possibilities for metalloprotein analysis [8].

Methodological Enhancements and Market Evolution

Recent technical improvements include the use of colored stacking gels containing acidic dyes (tartrazine, brilliant blue FCF, or new coccine) to facilitate well visualization and sample loading without affecting separation performance [18]. The electrophoresis market continues to evolve with trends toward automation, miniaturization, and integration of digital technologies [14] [10]. Capillary electrophoresis systems and microfluidic platforms are gaining traction for their ability to provide faster run times, reduced sample volumes, and automated data analysis, particularly in pharmaceutical quality control settings [10] [15]. Artificial intelligence is increasingly being applied to automate image analysis, band quantification, and pattern evaluation, reducing human error and enhancing reproducibility [15].

The principle of achieving a uniform charge-to-mass ratio through SDS binding remains the foundational concept that enables reliable protein separation by molecular weight. This technique continues to be indispensable in biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries, particularly for the characterization of therapeutic proteins and monoclonal antibodies [15]. While sophisticated alternatives like mass spectrometry have emerged, SDS-PAGE maintains its relevance due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and visual clarity [19]. Ongoing innovations in electrophoretic methodology ensure that this decades-old technique will continue to evolve, maintaining its critical role in proteomic research and drug development [8] [10].

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is a foundational reagent in protein biochemistry, most notably for its role in denaturing gel electrophoresis. Its functionality is governed by a critical physical property: the critical micelle concentration (CMC). This technical guide elucidates the molecular mechanism whereby SDS monomers, but not micelles, bind to and denature protein substrates. We detail the hydrophobic and electrostatic forces driving this selective interaction, summarize key quantitative data on SDS-protein binding, and provide validated experimental methodologies for investigating these interactions. Within the broader context of SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) research, understanding this monomer-centric mechanism is paramount, as it is the fundamental process that confers a uniform negative charge to polypeptides, enabling their separation by molecular mass rather than intrinsic charge.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is an anionic surfactant with a 12-carbon alkyl tail attached to a sulfate head group [20]. In aqueous solutions, its behavior is concentration-dependent. Below a specific threshold known as the critical micelle concentration (CMC), SDS exists as individual molecules, or monomers. Above the CMC, these monomers self-associate into spherical aggregates called micelles, wherein the hydrophobic tails are sequestered inward, and the negatively charged sulfate groups are exposed to the aqueous environment [21]. The CMC for SDS is typically in the range of 6–8 mM (approximately 0.17–0.23% w/v) [6] [21]. It is this monomeric form of SDS that is responsible for the initial binding and denaturation of proteins, a cornerstone of the SDS-PAGE technique [22].

The principle of SDS-PAGE relies on overcoming the inherent variations in protein charge and shape to separate them based solely on polypeptide chain length. This is achieved because SDS binds to proteins in a constant weight ratio, masking their intrinsic charge and imparting a similar charge-to-mass ratio [5] [6]. The ensuing separation through a polyacrylamide gel matrix, which acts as a molecular sieve, allows for the determination of protein molecular weight with an error of approximately ±10% [6].

The Molecular Mechanism of SDS-Protein Binding

The Primacy of Monomeric SDS

The fundamental tenet of SDS-protein interaction is that only the monomeric form of the amphiphile binds to proteins, not the micellar form [22]. This specificity arises from the structural and thermodynamic properties of the micelle. The SDS micelle is anionic on its surface and does not adsorb protein [6]. The hydrophobic core of the micelle is energetically stable, and incorporating a protein chain would be highly unfavorable. Instead, the cooperative binding process is driven by individual monomer units.

The process begins at very low SDS concentrations. At concentrations above 0.1 mM, the unfolding of proteins commences, and above 1 mM, most proteins are denatured [6]. The binding is cooperative, meaning the binding of one SDS molecule increases the probability that another will bind to the same protein chain [21]. This cooperative process saturates the protein backbone, with approximately 1.4 grams of SDS binding per gram of protein [6]. This ratio corresponds to roughly one SDS molecule per two amino acid residues, effectively coating the polypeptide chain [6].

Forces Driving Monomer Binding

The binding of SDS monomers to proteins is primarily hydrophobic in nature but is stabilized by electrostatic interactions [22].

- Hydrophobic Interactions: The aliphatic dodecyl chain of the SDS monomer interacts with non-polar regions and hydrophobic amino acid side chains on the protein. This interaction disrupts the hydrophobic core of the protein, leading to unfolding.

- Electrostatic Interactions: The negatively charged sulfate head group of SDS interacts with positively charged amino acid residues (e.g., lysine, arginine) on the protein. This interaction further destabilizes the protein's native structure by neutralizing positive charges.

Molecular dynamics simulation studies on human ubiquitin have shown that at high temperatures, SDS monomers disrupt the first hydration shell and expand the hydrophobic core, leading to complete protein unfolding [23]. The simulations also suggest that SDS can induce or stabilize α-helical structures in certain contexts, demonstrating the complex nature of the interaction [23].

Structural Evidence for Specific SDS Binding

While SDS binding is often considered non-specific, high-resolution structural studies have revealed that SDS can bind to pre-formed cavities in certain proteins. For instance, the X-ray crystal structure of the SDS complex with horse-spleen apoferritin showed that a single SDS molecule binds specifically in an internal cavity, with the alkyl tail bent into a horseshoe shape and the charged head group positioned at the cavity opening [24]. Isothermal titration calorimetry determined the dissociation constant for this specific interaction to be 24 ± 9 µM at 293 K, which is well below the CMC, confirming monomeric binding [24]. This demonstrates that beyond generalized coating, SDS can exhibit specific, high-affinity binding at discrete sites on some proteins.

Quantitative Data on SDS-Protein Interactions

The following tables summarize key quantitative data essential for understanding and experimenting with SDS-protein interactions.

Table 1: Key Properties of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

| Property | Value | Conditions / Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | 6–8 mM (0.17–0.23% w/v) | In aqueous solution | [21] |

| Molecular Weight (Monomer) | 288 Da | [21] | |

| Aggregation Number | 62 | Molecules per micelle | [6] [21] |

| Molecular Weight (Micelle) | ~18 kDa | [21] | |

| Typical SDS-PAGE Running Buffer Concentration | 0.1% (w/v) | ~3.5 mM, which is below the CMC | [6] |

| Typical SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer Concentration | 1-2% (w/v) | ~35-70 mM, well above the CMC | [20] |

| Average SDS Binding Ratio | 1.4 g SDS / 1 g protein | Corresponds to ~1 SDS molecule per 2 amino acids | [6] |

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Studying SDS-Protein Interactions

| Technique | Application | Key Measurable Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Direct measurement of binding affinity and thermodynamics. | Dissociation constant (Kd), enthalpy change (ΔH), stoichiometry (n). | [24] |

| X-ray Crystallography | High-resolution structural determination of SDS-protein complexes. | Atomic-level coordinates of SDS binding sites and protein conformational changes. | [24] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation | Theoretical study of binding pathways, kinetics, and unfolding mechanisms. | Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), residue-specific interactions. | [23] |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy | Monitoring changes in protein secondary structure upon SDS binding. | α-helical and β-sheet content, unfolding transitions. | [24] [23] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for SDS Binding

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating SDS binding to apoferritin [24].

Objective: To determine the binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS) of SDS monomer binding to a target protein.

Materials:

- Purified target protein (e.g., apoferritin)

- High-purity SDS

- ITC instrument (e.g., MicroCal VP-ITC)

- Dialysis buffer (e.g., 130 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0)

- Dialysis tubing

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Dialyze the target protein extensively against the chosen buffer to ensure precise buffer matching.

- Dissolve SDS in the same dialysate buffer used for the protein. The SDS concentration should be substantially higher than the protein concentration in the cell.

- Instrument Setup:

- Degas all solutions to prevent bubble formation during the titration.

- Load the sample cell (typically 1.4 mL) with the protein solution (e.g., 0.01 mM apoferritin).

- Load the syringe with the SDS solution (e.g., 3.47 mM).

- Titration Procedure:

- Set the reference power and stirring speed as per instrument guidelines.

- Program the titration parameters: initial delay, number of injections, injection volume (e.g., 1 µL first injection, followed by 15 µL injections), and duration between injections (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Begin the titration at a constant temperature (e.g., 293 K).

- Control Experiment:

- Perform an identical titration of SDS solution into buffer alone to measure the heat of dilution.

- Data Analysis:

- Subtract the control data from the protein titration data.

- Fit the corrected isotherm to an appropriate binding model (e.g., "single set of identical sites") using the instrument's software to extract Kd, n, and ΔH.

Protocol 2: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) for Functional Analysis

This protocol demonstrates how modifying SDS concentration can preserve protein function, underscoring the role of controlled monomer binding [8].

Objective: To separate proteins with high resolution while retaining native enzymatic activity and/or bound metal cofactors.

Materials:

- Standard SDS-PAGE equipment and precast Bis-Tris gels

- Protein sample (e.g., LLC-PK1 cell proteome fraction)

- Standard SDS-PAGE reagents (MOPS, Tris, etc.)

- NSDS-PAGE Sample Buffer: 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.01875% (w/v) Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% (w/v) Phenol Red, pH 8.5. No SDS or EDTA.

- NSDS-PAGE Running Buffer: 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7. No EDTA.

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Mix 7.5 µL of protein sample with 2.5 µL of 4X NSDS sample buffer. Do not heat the sample.

- Gel Pre-run:

- Mount the precast gel in the electrophoresis apparatus.

- Run the gel at 200V for 30 minutes in double-distilled H2O to remove storage buffer and unpolymerized acrylamide.

- Electrophoresis:

- Replace the water in the buffer chambers with NSDS-PAGE running buffer.

- Load the prepared samples and molecular weight markers.

- Run electrophoresis at a constant voltage of 200V for approximately 45 minutes until the dye front reaches the gel bottom.

- Analysis:

- Proteins can be analyzed for activity using in-gel zymography or for metal content using techniques like laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). This method has been shown to increase Zn²⺠retention in proteomic samples from 26% (standard SDS-PAGE) to 98% [8].

Visualizing the Mechanism and Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Mechanism of SDS Monomer Binding vs. Micelle Formation

Diagram 1: SDS Monomer Binding vs. Micelle Formation. This flowchart illustrates the concentration-dependent fate of SDS in solution and its consequence for protein binding. Below the CMC, monomers are available to cooperatively bind and unfold proteins. Above the CMC, stable micelles form which do not bind protein substrates.

Experimental Workflow for ITC Binding Studies

Diagram 2: ITC Workflow for SDS Binding. This workflow outlines the key steps for a successful Isothermal Titration Calorimetry experiment to quantify SDS-protein interactions, highlighting the critical need for buffer matching and control measurements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying SDS-Protein Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity SDS | Anionic detergent; core ligand for binding studies. Minimizes impurities that can interfere with assays. | All binding and electrophoresis studies. |

| Apoferritin | Model four-helix bundle protein with a defined internal cavity for specific SDS binding. | Structural and thermodynamic binding studies [24]. |

| Ubiquitin | Small, heat-stable model protein with mixed α/β structure. | Molecular dynamics and unfolding studies [23]. |

| ITC Instrument | Measures heat released or absorbed during molecular binding events. | Direct measurement of binding constants and thermodynamics [24]. |

| Precast Bis-Tris Gels | Polyacrylamide gels with near-neutral pH; stable and reduce protein modification. | Standard and Native SDS-PAGE [8] [6]. |

| MOPS Buffer | Buffer for SDS-PAGE running buffer (pH ~7.7). | Maintaining stable pH during electrophoresis [8]. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Discontinuous buffer system for standard SDS-PAGE. | Stacking and separating proteins based on size [6] [25]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent; cleaves disulfide bonds to ensure complete unfolding. | Standard SDS-PAGE sample preparation [6]. |

| CHAPS Detergent | Zwitterionic, non-denaturing detergent. Used as a milder alternative for comparison. | Membrane protein solubilization without denaturation [21]. |

| 1-(3-Chloro-4-methylphenyl)urea | 1-(3-Chloro-4-methylphenyl)urea|CAS 13142-64-8 | 1-(3-Chloro-4-methylphenyl)urea is a chemical for research use only (RUO). It is a phenylurea compound studied in environmental analysis and medicinal chemistry. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-t-Butyl-4-quinoline carboxylic acid | 2-t-Butyl-4-quinoline carboxylic acid, MF:C14H15NO2, MW:229.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of protein research, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as a fundamental analytical technique for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. The core principle of SDS-PAGE relies on the complete denaturation of proteins into their linear polypeptide forms, and this is where the essential partnership between SDS and reducing agents comes into play. While SDS is responsible for disrupting non-covalent bonds and imparting a uniform negative charge, it is incapable of breaking the strong covalent disulfide bonds that stabilize tertiary and quaternary protein structures. These disulfide bridges, formed between cysteine residues, can maintain structural domains even in the presence of detergents, potentially leading to inaccurate molecular weight determination and poor separation efficiency. The introduction of reducing agents such as Dithiothreitol (DTT) and β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) is therefore critical to achieve complete protein denaturation by specifically targeting and reducing these disulfide bonds, enabling proteins to be separated solely based on polypeptide chain length.

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the synergistic relationship between SDS and reducing agents in protein biochemistry. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the mechanisms, applications, and practical protocols essential for effective protein analysis, with a specific focus on the comparative advantages of DTT and BME in experimental workflows.

The Fundamental Principles of SDS-PAGE

The Indispensable Role of SDS

SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) is a powerful anionic detergent that serves two primary functions in protein denaturation for electrophoresis. First, it effectively disrupts nearly all non-covalent interactions—including hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic forces, and ionic bonds—that maintain a protein's secondary and tertiary structure [26]. This action "unfolds" the protein, destroying its higher-order organization. Second, SDS binds to the denatured protein backbone at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g of SDS per gram of polypeptide [27]. This uniform binding masks the protein's intrinsic charge and imparts a large, negative net charge that is roughly proportional to the protein's molecular mass [5] [28]. The result is the formation of SDS-polypeptide complexes that share a similar charge-to-mass ratio, ensuring that separation during electrophoresis is based primarily on molecular size rather than native charge or shape [26].

The Limitation of SDS and the Need for Reducing Agents

Despite its effectiveness against non-covalent bonds, SDS has a critical limitation: it is incapable of breaking covalent disulfide bonds (-S-S-). These bonds, which form between the sulfur atoms of cysteine residues, are a key feature of the three-dimensional structure of many proteins and are essential for stabilizing the quaternary structure of multimetric proteins [29]. If left intact, disulfide bonds can prevent complete protein unfolding, leading to aberrant migration during electrophoresis and inaccurate molecular weight estimates. This creates an imperative for reducing agents, which are specifically designed to reduce these disulfide bonds into free sulfhydryl groups (-SH), thereby completing the denaturation process initiated by SDS [29].

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic denaturation process involving both heat, SDS, and a reducing agent (like DTT or BME) to fully unfold a protein for SDS-PAGE.

Synergistic Protein Denaturation for SDS-PAGE

The Science of Reducing Agents

Mechanism of Disulfide Bond Reduction

Reducing agents function by participating in a thiol-disulfide exchange reaction, wherein their own free thiol (-SH) groups nucleophilically attack the sulfur-sulfur bond in a protein's disulfide bridge. This reaction reduces the protein's disulfide bond, converting it into two free thiol groups, while the reducing agent itself becomes oxidized [30]. For the reduction to be effective in a typical biochemical context, the reducing agent must possess a lower redox potential than the protein's disulfide bond, making the reaction thermodynamically favorable. The efficiency of this process is further enhanced by the application of heat (95°C), which increases molecular motion and accelerates both the denaturation by SDS and the reduction of disulfide bonds [31]. This combination of chemical reduction and thermal energy ensures that proteins are fully unfolded into linear polypeptides, ready for accurate electrophoretic separation.

Dithiothreitol (DTT) - The Reagent of Choice

Dithiothreitol (DTT), also known as Cleland's reagent, is a potent reducing agent that has become the standard in many protein biochemistry applications. Its mechanism involves two sequential thiol-disulfide exchange reactions. First, a mixed disulfide intermediate is formed between one of DTT's thiol groups and the protein's disulfide bond. Subsequently, an intramolecular cyclization of DTT occurs, resulting in a stable six-membered ring (a cyclic disulfide) and the release of the fully reduced protein with its free thiol groups [30]. This cyclic reaction is highly favorable, driving the reduction to completion.

DTT is particularly valued for its strong reducing power, lower volatility, and significantly less unpleasant odor compared to BME [30]. A typical working concentration for DTT in sample buffer is between 40-160 mM [29]. However, DTT has a key limitation: its reducing power diminishes in acidic conditions (pH < 7) due to the protonation of its thiol groups, which are necessary for the nucleophilic attack [30]. Furthermore, DTT solutions are prone to oxidation by air and must be prepared fresh or stored frozen in aliquots to maintain efficacy.

β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) - A Traditional Agent

β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) is a traditional reducing agent that has been widely used for decades, famously featured in Laemmli buffer. It operates through a mechanism similar to DTT, using its single thiol group to reduce protein disulfide bonds, resulting in the formation of oxidized BME dimers. However, BME is generally considered less effective than DTT due to its weaker reducing power. It is also highly volatile, which contributes to its characteristically strong, unpleasant odor that can permeate laboratory environments [30] [29]. This volatility can also lead to a gradual loss of reducing capacity from an opened container. Despite these drawbacks, BME remains in use due to its lower cost and established history in certain protocols.

Comparative Analysis of DTT and BME

The choice between DTT and BME can significantly impact experimental outcomes, cost, and laboratory working conditions. The following table provides a detailed, quantitative comparison to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate agent.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of DTT and β-Mercaptoethanol

| Parameter | Dithiothreitol (DTT) | β-Mercaptoethanol (BME) |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Structure | HOOC-CH(NHâ‚‚)-CHâ‚‚-SH | HO-CHâ‚‚-CHâ‚‚-SH |

| Mechanism | Two-step reaction forming a stable cyclic disulfide [30] | Simple thiol-disulfide exchange, forming oxidized dimers |

| Typical Working Concentration | 40-160 mM [29] | Often used at ~1% (v/v) or ~140 mM in sample buffer [31] |

| Reducing Power | Stronger reducing agent [30] | Weaker reducing agent [30] |

| Odor & Volatility | Lower volatility, less unpleasant odor [30] | High volatility, very strong and unpleasant odor [30] [29] |

| Stability in Solution | Prone to oxidation; prepare fresh or store at -20°C [30] | Solutions lose potency over time due to volatility and oxidation |

| Cost (Example) | $56.25 for 10 g [30] | Generally less expensive |

| Effective pH Range | Most effective at pH > 7 [30] | Effective over a broader pH range |

Advanced Applications and Methodological Considerations

Detailed Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE with Reducing Agents

A robust, reproducible protocol is essential for high-quality protein separation. The following detailed methodology incorporates the critical steps for effective protein denaturation using reducing agents.

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation

| Reagent | Composition / Purpose | Typical Concentration / Note |

|---|---|---|

| 4X Sample Loading Buffer (Laemmli Buffer) | Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), SDS, Glycerol, Bromophenol Blue, Reducing Agent [28] | Contains 2% SDS, 20% Glycerol, 160 mM DTT (or 1-5% BME) [29] |

| SDS | Anionic detergent; denatures proteins and imparts charge [26] | Final conc. 1-2% in sample [29] |

| DTT | Reducing agent; breaks disulfide bonds [30] | Final conc. 40-160 mM; preferred over BME [29] |

| BME | Alternative reducing agent [28] | Final conc. ~1-5% (v/v); strong odor [31] |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for easy well loading [29] | 10-20% final concentration |

| Bromophenol Blue | Tracking dye for monitoring electrophoresis progress [29] | ~0.05 mg/ml final concentration |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute your protein sample to a predetermined concentration in an appropriate buffer. A final concentration of 1-2 mg/mL after mixing with sample buffer is often suitable for complex mixtures, though this may require optimization [29].

- Denaturation Mix Preparation: Combine the protein sample with an equal volume of the 4X Sample Loading Buffer containing the chosen reducing agent (DTT or BME). For instance, mix 10 µL of protein sample with 2.5 µL of 4X buffer and 7.5 µL of water, ensuring the final concentration of SDS is ~1% and DTT is ~40-160 mM [29] [31].

- Heat Denaturation: Cap the tubes securely and heat the mixture at 90-100°C for 3-10 minutes in a heat block or boiling water bath [5] [31]. This critical step accelerates the denaturation by SDS and the reduction of disulfide bonds by DTT/BME. Caution: Tube caps may pop open due to pressure build-up; use tube clamps if available.

- Brief Centrifugation: Pulse-centrifuge the heated samples (e.g., 15,000 rpm for 1 minute) to collect any condensation and ensure the entire sample is at the bottom of the tube [31].

- Gel Loading and Electrophoresis: Load the denatured, reduced samples into the wells of a pre-cast polyacrylamide gel. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 120-150 V for the separating gel) until the bromophenol blue dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [26].

The workflow below summarizes the key steps in preparing and running a reducing SDS-PAGE experiment.

SDS-PAGE Sample Prep Workflow

Specialized Applications in Research and Industry

The synergy of SDS and reducing agents extends far beyond basic protein analysis, playing a vital role in advanced research and industrial quality control.

- Protein Purity and Expression Analysis: SDS-PAGE is a cornerstone for assessing the purity of recombinant protein preparations and analyzing protein expression levels in cell lysates. The complete denaturation ensured by SDS and DTT/BME allows researchers to visualize individual polypeptide chains and identify contaminants [8].

- Western Blotting: The technique is a prerequisite for western blotting, where proteins separated by SDS-PAGE are transferred to a membrane for immunodetection. Consistent and complete reduction is critical for antibody recognition of linear epitopes [8].

- Food Science and Quality Assurance: In the food industry, SDS-PAGE is used to characterize protein ingredients, verify authenticity, detect adulteration, and assess the impact of processing (e.g., heat or enzymatic hydrolysis) on protein molecular weight profiles [32].

- Metalloprotein Studies and Alternative Methods: While standard SDS-PAGE destroys native protein function, modified methods like Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) have been developed. This technique uses minimal SDS and omits reducing agents and heat, allowing for the separation of proteins while retaining bound metal ions and, for some enzymes, catalytic activity [8]. This highlights a specific use case where the omission of DTT/BME is deliberate to preserve a functional characteristic.

The powerful synergy between SDS and reducing agents like DTT and BME is a cornerstone of modern protein science. While SDS unfolds protein structures and standardizes charge, it is the specific action of DTT and BME in breaking resilient disulfide bonds that ensures complete denaturation into linear polypeptides. This partnership is fundamental to the success of SDS-PAGE, enabling the high-resolution separation of proteins based on molecular weight that underpins countless applications in research, diagnostics, and product development. The choice between reducing agents, particularly the more potent and less odorous DTT versus the traditional BME, requires careful consideration of the specific experimental needs and conditions. As protein analysis continues to evolve, the precise control of reduction states—whether for full denaturation or for the preservation of native complexes in techniques like NSDS-PAGE—will remain an essential skill for scientists driving innovation in biotechnology and drug development.

Mastering the SDS-PAGE Protocol: From Sample Prep to Precise Molecular Weight Determination

In the realm of protein research, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) stands as a cornerstone technique for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. [5] [33] This method's unparalleled effectiveness hinges on a critical preliminary step: the complete denaturation of protein samples using an SDS-based buffer and controlled heat. [34] [35] Within the broader context of understanding SDS's role in polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis research, sample preparation emerges not merely as a routine procedure but as the foundational process that determines the entire experiment's validity and resolution. The intentional and complete unfolding of proteins is what allows SDS-PAGE to separate molecules primarily by size, effectively neutralizing the influence of innate protein charge and complex three-dimensional structure. [33] [6] For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering this denaturation process is therefore not a mere technicality but a prerequisite for obtaining accurate, reproducible, and interpretable data in applications ranging from western blotting and mass spectrometry to protein purity assessment and molecular weight estimation. [34] [35]

The Chemical Basis of Denaturation

The Action of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is a powerful anionic detergent that serves as the primary denaturing agent in the sample buffer. [36] Its mechanism of action is twofold. First, the hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail of SDS interacts with and dissolves the hydrophobic regions of the protein, while the ionic sulfate group disrupts non-covalent ionic bonds that maintain secondary and tertiary structure. [34] [36] This concerted action causes the protein to lose its higher-order structures and unfold into a linear polypeptide chain. [36]

Second, SDS binds to the unfolded protein backbone at a remarkably constant weight ratio of approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per 1 gram of protein. [6] [35] This uniform coating imparts a strong negative charge to the polypeptide that is directly proportional to its chain length. Consequently, all proteins in the sample achieve a similar charge-to-mass ratio, ensuring that their electrophoretic mobility through the gel becomes a function of molecular size alone, rather than a combination of size, shape, and intrinsic charge. [5] [33] [35] It is this fundamental principle, established during sample preparation, that underpins the entire SDS-PAGE technique.

The Supporting Role of Reducing Agents and Heat

While SDS is the principal denaturant, its effect is significantly potentiated by reducing agents and heat, which target the remaining structural elements holding the protein in a native conformation.

- Reducing Agents: Compounds such as β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) or dithiothreitol (DTT) are added to the sample buffer to cleave disulfide bonds, which are covalent linkages that stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures. [34] [35] By breaking these sulfur bridges, reducing agents ensure that multimeric proteins dissociate into their individual subunits and that all proteins are fully linearized, further promoting the spaghettification of the polypeptide chain. [34]

- Heat: The application of heat, typically 95°C for 3-5 minutes or 70°C for 10 minutes, provides the kinetic energy needed to overcome hydrogen bonding and other stabilizing interactions that SDS alone may not disrupt. [5] [6] Boiling also serves a practical purpose by homogenizing the sample, particularly for cell lysates that may contain viscous DNA. The heat melts the DNA, reducing gumminess and making the sample easier to pipette into the gel wells. [34]

Table 1: Key Components of SDS Sample Denaturation Buffer and Their Functions

| Component | Typical Concentration | Primary Function | Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | 1-2% [36] | Denaturant & Charge Provider | Disrupts hydrophobic/ionic bonds; coats proteins with uniform negative charge. [34] [36] |

| Reducing Agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol or DTT) | β-ME: 1-5% [6]DTT: 10-100 mM [6] | Disulfide Bond Reduction | Cleaves covalent -S-S- bridges, ensuring full dissociation and linearization. [6] [35] |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | 50-200 mM, pH ~6.8 [36] | pH Stabilization | Maintains stable pH environment for the denaturation process. [36] |

| Glycerol | 10-20% [36] | Density Agent | Adds density to sample, allowing it to sink to bottom of loading well. [36] [35] |

| Bromophenol Blue | Trace | Tracking Dye | Visualizes sample migration during electrophoresis. [36] [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Optimal Denaturation

The following section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for the denaturation of protein samples prior to SDS-PAGE. Adherence to this protocol is critical for achieving consistent and reliable results.

Reagent Preparation

Laemmli Sample Buffer (2X Concentrate) A standard, widely used formulation is the Laemmli buffer. [36] To prepare 10 mL of a 2X stock solution:

- 4.0 mL of 1.0 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8

- 2.0 mL of 20% (w/v) SDS (Final concentration ~4%)

- 2.0 mL of Glycerol (Final concentration 20%)

- 0.5 mL of β-Mercaptoethanol (Final concentration 5%) or 0.77 g of DTT (Final concentration ~0.5 M)

- 1.5 mL of Deionized Water

- A few grains of Bromophenol Blue (approx. 0.002%)

Mix the components thoroughly. The buffer can be aliquoted and stored at -20°C for several months. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles for aliquots containing reducing agents.

Step-by-Step Denaturation Procedure

Sample and Buffer Mixing:

Heat Denaturation:

- Secure the cap of the microcentrifuge tube to prevent popping.

- Place the tube in a pre-heated heat block or water bath set to 95°C for 3-5 minutes. [5] [6]

- Critical Note: The optimal heating time can be protein-dependent. Large or complex proteins may require extended heating for complete denaturation, while prolonged boiling can degrade smaller proteins. Empirical testing is recommended for new protein systems. [34]

Brief Centrifugation:

- After heating, centrifuge the samples at high speed (e.g., 15,000 rpm) for 1 minute at room temperature or 4°C. [5]

- This step collects any condensation from the tube walls and sediments any insoluble material.

Sample Loading:

- The sample is now ready for loading onto the polyacrylamide gel. Use the supernatant for electrophoresis, being careful not to disturb any pellet. [5]

The workflow below summarizes the sample preparation process.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with a standardized protocol, researchers may encounter issues stemming from suboptimal denaturation. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Sample Denaturation in SDS-PAGE

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing Bands | Incomplete denaturation [34]; Insufficient reducing agent; Protein degradation. | Ensure fresh reducing agent is used; Increase heating time or temperature; Perform all steps on ice with protease inhibitors. |

| Atypical Band Migration | Over-heating leading to protein degradation [34]; Incomplete disaggregation. | Optimize heating time; Ensure sample is fully mixed and dissolved in buffer. |

| Poor Resolution of Similar Sized Proteins | Inefficient stacking due to improper buffer pH or ionic content. [36] | Verify pH of sample buffer and gel buffers; Use fresh running buffer. |

| No or Weak Bands | Over-heating of small, labile proteins [34]; Insufficient protein loaded. | Reduce heating time for small proteins; Concentrate protein sample prior to loading. |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation

Successful and reproducible sample denaturation requires precise formulation of reagents. The following table details the essential materials for this critical step.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation

| Item | Specifications & Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | >99% purity; Anionic detergent for protein denaturation and charge conferment. [36] | Prepare as 10-20% (w/v) stock solution in water. Filter through a 0.22 µm filter. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | High-purity; Reducing agent for cleaving disulfide bonds. [6] | Preferred over β-ME for lower odor. Prepare as 1M stock, aliquot, and store at -20°C. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | 1.0 M, pH 6.8; Provides optimal pH environment for denaturation and stacking. [36] | Confirm pH at room temperature. Sterile filter for long-term storage. |

| Glycerol | Molecular biology grade; Adds density to sample for easy gel loading. [35] | |

| Bromophenol Blue | Tracking dye for monitoring electrophoresis progress. [36] [35] | Typically added in trace amounts to the sample buffer. |

| Laemmli Buffer (2X) | Ready-to-use denaturing buffer containing all above components. [36] | Available commercially for convenience and consistency. |

| 2-(2-Chlorophenyl)acetohydrazide | 2-(2-Chlorophenyl)acetohydrazide, CAS:22631-60-3, MF:C8H9ClN2O, MW:184.62 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-(4-(Chlorosulfonyl)phenyl)propanoic acid | 3-(4-(Chlorosulfonyl)phenyl)propanoic acid, CAS:63545-54-0, MF:C9H9ClO4S, MW:248.68 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The denaturation of proteins with SDS buffer and heat is a deceptively simple yet profoundly critical step that dictates the success of subsequent SDS-PAGE analysis. This process, which intentionally dismantles native protein structures to create uniformly charged linear polypeptides, is the very foundation upon which the technique's principle of size-based separation is built. [5] [33] [35] A thorough understanding of the biochemical roles of SDS, reducing agents, and heat—coupled with meticulous execution of the preparation protocol—empowers researchers to generate high-quality, interpretable data. As SDS-PAGE continues to be an indispensable tool in proteomics, biomarker discovery, and biopharmaceutical development, the precision applied in these initial steps remains a fundamental determinant of experimental rigor and reliability.

Within the framework of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), a technique foundational to modern biochemistry and drug development, the stacking gel performs a critical, yet often overlooked, function. This in-depth technical guide elucidates the science behind this essential first step. The stacking gel leverages a discontinuous buffer system to concentrate disparate protein samples into ultrasharp bands before they enter the resolving gel, thereby ensuring the high-resolution separation that SDS-PAGE is renowned for. This article will deconstruct the underlying principles of this stacking phenomenon, provide detailed methodologies, and present quantitative data, firmly framing the discussion within the broader context of SDS's role in revolutionizing protein analysis by conferring a uniform charge-to-mass ratio and denaturing proteins to allow separation primarily by molecular weight [2] [37].