Protein Staining Methods Compared: A Guide to Sensitivity, Applications, and Optimization for Research

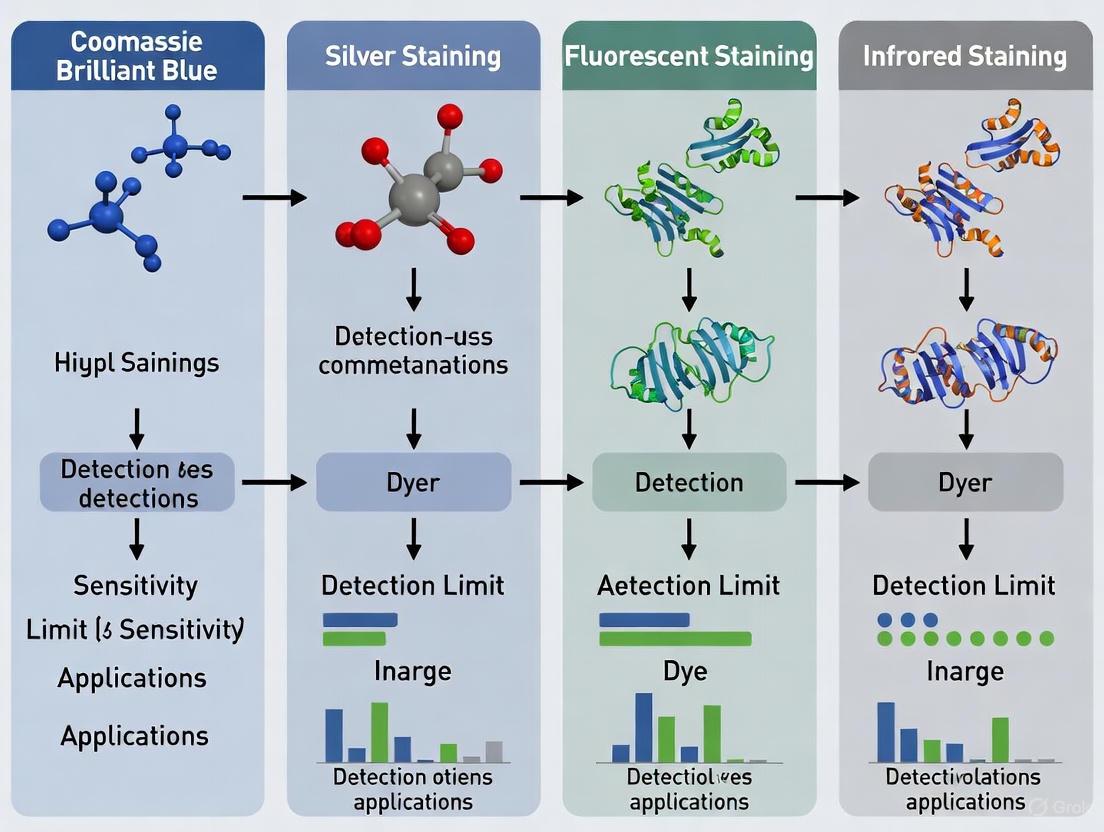

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of major protein staining methods, including Coomassie, silver, fluorescent, and zinc stains, for researchers and drug development professionals.

Protein Staining Methods Compared: A Guide to Sensitivity, Applications, and Optimization for Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of major protein staining methods, including Coomassie, silver, fluorescent, and zinc stains, for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, sensitivity ranges, and protocol times to guide method selection. The content delves into practical applications, compatibility with downstream analysis like mass spectrometry, and advanced troubleshooting for common issues such as high background and low sensitivity. Furthermore, it explores validation strategies, the growing evidence supporting total protein staining for normalization over traditional housekeeping proteins, and the impact of new technologies on quantitative accuracy and multiplexing capabilities in biomedical research.

Protein Staining Fundamentals: Principles, Types, and Detection Limits

The efficacy of biomedical research and drug development hinges on the precise visualization of proteins and cellular structures. Core staining principles—encompassing sample fixation, dye binding, and detection methodologies—form the foundational framework for reliable data interpretation. Within this context, the choice between colorimetric and fluorescent detection represents a critical decision point, each with distinct advantages for sensitivity, quantification, and multiplexing. This guide objectively compares the performance of these staining methods, grounded in a broader thesis on optimizing protein staining efficiency for heterogeneous samples. We synthesize current experimental data to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based protocols and comparative analyses to inform their methodological selections.

Core Staining Principles

Fixation

Fixation is the crucial first step to preserve cellular architecture and prevent degradation. The primary function of fixatives like 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) is to stabilize proteins and cellular components, making them insoluble while maintaining structural integrity for subsequent analysis [1]. For fresh tissue evaluation in virtual pathology, fixation steps may be bypassed entirely using rapid optical sectioning techniques, underscoring the context-dependency of fixation protocols [2].

Dye Binding Mechanisms

Dye binding encompasses various biochemical interactions that enable specific visualization of cellular components:

- Electrostatic Interactions: Basic dyes like crystal violet bind to negatively charged cellular components through ionic attraction, forming the basis for differential stains like Gram staining [3].

- Intercalation and Minor Groove Binding: Fluorescent nuclear dyes such as DRAQ5 and SYBR Gold intercalate between DNA base pairs or bind to the minor groove, providing specific nuclear labeling [2].

- Protein-Dye Interactions: Coomassie Blue binds positively charged amino acid residues through electrostatic and van der Waals forces for total protein staining [4].

- Covalent and Affinity Binding: Targeted fluorescent probes use high-affinity interactions between targeting groups (e.g., antibodies) and specific epitopes, with fluorophores serving as detection tags [3].

Detection Modalities: Fundamental Differences

The detection modality determines measurement sensitivity, dynamic range, and application suitability:

- Colorimetric Detection relies on measurement of colored compounds using absorbance of specific light wavelengths. It is generally less sensitive but technically simpler and more cost-effective [4].

- Fluorometric Detection measures fluorescent emission following light excitation at specific wavelengths. It offers higher sensitivity due to low background signals and greater dynamic range, enabling detection of low-abundance targets [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Detection Modalities

| Characteristic | Colorimetric Detection | Fluorometric Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Absorbance measurement | Fluorescence emission |

| Sensitivity | Lower | Higher |

| Dynamic Range | Narrower | Wider |

| Background Signal | Higher | Lower (especially with fluorogenic probes) |

| Multiplexing Capability | Limited | Excellent |

| Instrument Cost | Generally lower | Generally higher |

| Example Applications | Alkaline phosphatase assays, ELISA, total protein staining [4] | Confocal microscopy, flow cytometry, real-time imaging [2] |

Comparative Performance Data

Quantitative Comparison of Staining Methods

Recent diagnostic studies provide robust comparative data on staining performance metrics across multiple parameters:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Staining and Detection Methods

| Method / Dye | Accuracy vs. H&E Standard | Time Requirements | Image Quality/SNR | Photostability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy (FCM) | 95.2% (Pathologist 1) 85.7% (Pathologist 2) [5] | Mean acquisition: 7 minutes [5] | High (Acceptable quality in 96.2% of cases) [5] | Varies by dye | Rapid evaluation of IR-guided CNBs [5] |

| Digital H&E Staining (CycleGAN) | Structural similarity (SSIM ∼0.95) to chemical staining [6] | Computational (bypasses chemical staining) | High (10% chromatic discrepancy) [6] | N/A (computational) | Digital pathology from label-free images [6] |

| Total Protein Staining | Superior for heterogeneous samples [1] | Varies by protocol | N/A | N/A | Normalization for Western blotting of heterogeneous tissues [1] |

| DRAQ5 (Nuclear) | N/A | Optimal: 180s [2] | High SNR with PBS solvent [2] | High [2] | Nuclear staining for fresh tissue microscopy [2] |

| SYBR Gold (Nuclear) | N/A | Optimal: 180s [2] | High SNR with PBS solvent [2] | Moderate to High [2] | Nuclear staining for fresh tissue microscopy [2] |

| TO-PRO3 (Nuclear) | N/A | Optimal: 180s [2] | Moderate SNR [2] | Lower [2] | Nuclear staining for fresh tissue microscopy [2] |

| Eosin Y515 (Cytoplasmic) | N/A | Protocol-dependent | High for ECM [2] | Lower [2] | Cytoplasmic/ECM staining [2] |

Experimental Protocol: Fluorescence Confocal Microscopy for Core-Needle Biopsy

This protocol, adapted from a diagnostic study comparing FCM with H&E-stained sections, enables real-time bedside evaluation of biopsies [5]:

- Sample Acquisition: Procure one core-needle biopsy (CNB) specimen per patient using a semiautomatic side-cutting core gun set (e.g., Quick-Core or Mission) for 1-2 cm long specimens.

- Staining: Place specimen in a petri dish and stain with 0.6mM acridine orange for approximately 10 seconds.

- Image Acquisition: Transfer specimen to FCM platform (e.g., Vivascope 2500 RSG4) in the radiology suite. Scan using 488 nm and 785 nm lasers with a ×40 oil immersion objective (numerical aperture 0.9). Acquire images at 9 frames per second with composite image size of 2.0 cm at greatest diameter.

- Image Interpretation: Examine grayscale and digitally pseudocolorized blue images at various magnifications (×1 to ×60 equivalent). Grade image quality semiquantitatively (0=None interpretable; 3=≥50% interpretable). Categorize findings as nondiagnostic, benign, atypical, suspicious, or malignant.

- Post-Imaging Processing: After FCM imaging, fix CNB tissue in 10% formalin and process routinely to generate 5-μm formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks for H&E staining and histopathologic correlation.

Experimental Protocol: Assessment of Fluorescent Dyes for Virtual Pathology

This systematic protocol for evaluating fluorescent dyes enables optimization of staining parameters for fresh tissue microscopy [2]:

- Sample Preparation: Use fresh, non-fixed, non-optically cleared tissue specimens of consistent type.

- Dye Preparation: Prepare nuclear dyes (DRAQ5, TO-PRO3, SYBR Gold) and cytoplasmic/ECM dyes (Eosin Y515, Atto488) in various solvents (PBS, ethanol) at multiple concentrations.

- Staining Procedure: Apply dye solutions to tissue specimens with variation in staining time (e.g., 0-600 seconds). Test different rinsing solutions (PBS, deionized water, ethanol) after staining.

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Image samples using structured illumination microscopy (SIM) to achieve optical sectioning. Quantify signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast for each parameter combination. Assess temporal degradation and photobleaching effects over time.

- Data Interpretation: Identify optimal staining parameters (solvent, concentration, staining time, rinsent) that maximize SNR and contrast while maintaining acceptable photostability.

Visualization of Staining Principles

Staining and Detection Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Core staining workflow from fixation to detection.

Experimental Workflow for Staining Optimization

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for staining optimization.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Staining and Detection

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Staining Dyes | DRAQ5, SYBR Gold, TO-PRO3, RedDot1, Acridine Orange [5] [2] | Label DNA in cell nuclei for fluorescence microscopy and virtual pathology |

| Cytoplasmic/ECM Staining Dyes | Eosin Y515, Atto488, Rhodamine B, Sulforhodamine 101 [2] | Label cytoplasmic and extracellular matrix structures |

| Total Protein Stains | Coomassie Blue, Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assay reagents [1] [4] | Normalization for Western blotting; superior for heterogeneous samples |

| Fixation Agents | 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF), Ethanol [1] [2] | Preserve cellular architecture and prevent degradation |

| Solvents & Rinsing Solutions | Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS), Deionized Water, Ethanol [2] | Dissolve dyes and rinse excess stain; PBS optimal for many fluorescent dyes |

| Fluorogenic Probes | ACC-based substrates, DDAO-derivatives [3] | Activated by specific biochemical processes; reduce background fluorescence |

| Traditional Histology Stains | Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Crystal Violet, Methylene Blue [5] [3] | Standard histological staining for colorimetric detection |

| Bio-orthogonal Tags | Click chemistry reagents (e.g., azide/alkyne tags) [3] | Minimal tags for two-step detection strategies; increase bio-compatibility |

The comparative analysis of staining principles and detection methodologies reveals a nuanced landscape for research applications. Fluorescent detection methods generally offer superior sensitivity, temporal resolution, and multiplexing capabilities, particularly valuable for real-time assessment of fresh tissues and quantification of low-abundance targets [5] [2] [4]. Colorimetric methods remain robust for many applications, offering simplicity and cost-effectiveness with adequate sensitivity for numerous research contexts [4]. Critical considerations for method selection include sample heterogeneity, quantification requirements, and need for multiplexing. For heterogeneous tissue samples, total protein staining provides more reliable normalization than housekeeping proteins [1]. Emerging technologies like fluorescence confocal microscopy and computational staining approaches offer promising avenues for enhancing diagnostic speed and accuracy while preserving sample integrity [5] [6]. The optimal staining strategy ultimately depends on specific research objectives, sample characteristics, and analytical requirements, with this comparison providing a framework for evidence-based methodological decisions.

In the realm of protein analytics, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis serves as a cornerstone technique for separating complex protein mixtures. However, since separated proteins are not visible to the naked eye, staining is an indispensable step for their visualization and analysis. Among the various staining methods available, Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining maintains its status as a fundamental workhorse for routine protein visualization in laboratories worldwide [7]. Its enduring popularity stems from an effective balance of sensitivity, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness, making it an ideal choice for many applications in basic research, biotechnology, and drug development [7].

This guide provides an objective comparison of Coomassie staining's performance against other common staining alternatives. We summarize quantitative data on sensitivity and linear dynamic range, detail standardized experimental protocols, and place its utility within the broader context of protein analysis. By presenting both its capabilities and limitations, we aim to provide researchers with a clear framework for selecting the most appropriate staining method for their specific experimental needs.

Coomassie Blue: Mechanisms and Variants

Chemical Principles of Protein Binding

Coomassie Brilliant Blue is an anionic synthetic dye belonging to the triphenylmethane family. Its mechanism of action involves non-covalent binding to proteins, primarily through two types of interactions [7]. First, the dye's negatively charged sulfonic acid groups form ionic bonds with positively charged basic amino acid residues, such as arginine, lysine, and, to a lesser extent, histidine [7]. Second, van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions drive the binding of the dye to aromatic residues and the protein backbone [7].

Upon binding to proteins, the dye undergoes a spectral shift. For instance, the free Coomassie Blue G-250 dye is red in its cationic form at very low pH, turns green in its neutral form, and becomes blue as an anion at higher pH levels. When it binds to protein regions, this equilibrium shifts, and the stable blue anionic form predominates, producing distinct blue-stained protein bands against a clear background [7]. This binding is sufficiently mild to keep the protein structure intact for downstream applications [7].

Common Coomassie Blue Variants

There are two primary forms of Coomassie dye, which have distinct properties and applications [7]:

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250: The "R" denotes a reddish hue. This variant is typically dissolved in methanol-acetic acid mixtures and often requires a destaining step to reduce background [7] [8].

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250: The "G" signifies a greenish hue. This form is frequently used in colloidal staining formulations, where the dye aggregates in the presence of salts like ammonium sulfate or aluminium sulfate in acidic alcoholic media [9]. These colloidal particles are less permeable into the gel matrix, resulting in significantly lower background staining and often eliminating the need for a destaining step [9]. G-250 is also the key component in the Bradford protein assay [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Coomassie Blue Dye Variants

| Feature | Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 | Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 |

|---|---|---|

| Color Hue | Reddish ("R") [7] | Greenish ("G") [7] |

| Common Form | Soluble in methanol/acetic acid [8] | Colloidal suspensions [9] |

| Staining Speed | Generally faster [10] | May require longer incubation [10] |

| Sensitivity | Less sensitive (~200 ng/band) [9] | More sensitive (can detect <10 ng/band) [10] [9] |

| Background | Often requires destaining [8] | Low background; destaining may be optional [9] |

| Primary Use | Traditional gel staining, IEF gels [7] | Colloidal staining, Bradford protein assay [7] |

Performance Comparison of Protein Staining Methods

Quantitative Comparison of Sensitivity and Dynamic Range

When selecting a staining method, researchers must balance sensitivity, quantitative linearity, cost, and procedural complexity. The table below provides a direct comparison of Coomassie staining with other common protein visualization methods.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Common Protein Staining Methods

| Staining Method | Detection Limit (Per Band) | Linear Dynamic Range | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Blue (R-250) | ~200 ng [9] | Microgram level, wide linear range [8] | Inexpensive, simple protocol, good MS compatibility [7] [8] | Lower sensitivity, time-consuming destaining [7] |

| Colloidal Coomassie (G-250) | < 10 ng [11] to 1 ng [9] | ~5 ng to 500 ng [11] | Excellent sensitivity, low background, best CBB for quantitation [10] [9] | Slower staining process [11] |

| Silver Staining | < 0.25 ng – 1 ng [10] | Narrow | Highest sensitivity [10] | Complex protocol, low MS compatibility, non-linear quantification [9] |

| Fluorescent Stains (e.g., SYPRO Ruby) | < 1 ng – 2.5 ng [12] | Wide | High sensitivity, wide dynamic range, good MS compatibility [12] | Expensive, requires fluorescence imaging equipment [12] |

| Near-Infrared CBB Fluorescence | < 1 ng [12] | Significantly exceeds Sypro Ruby [12] | Highest CBB sensitivity, very wide dynamic range, cost-effective [12] | Not a standard application, requires NIR imaging |

A 2024 study highlighted a critical limitation of colorimetric total protein assays like Coomassie Bradford, noting they can significantly overestimate the concentration of target transmembrane proteins in heterogeneous samples compared to specific methods like ELISA [13]. This is a crucial consideration when working with complex protein mixtures or membrane preparations.

Staining Efficiency is Protein-Dependent

It is vital to recognize that staining efficiency can vary depending on the protein of interest. A study on wheat gluten proteins demonstrated that the staining efficiency varied per protein across different methods, and no single method achieved complete staining of all gluten proteins [14]. This protein-to-protein variability underscores the importance of method validation when working with specific protein systems.

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Standard Coomassie Staining and Destaining Protocol

The following workflow outlines a classic protocol for R-250 staining, which can be adapted based on specific reagent formulations.

Classic R-250 Staining Procedure [7] [8]:

- Fixation: After electrophoresis, transfer the gel to a container and immerse it in a fixing solution (e.g., 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid) for 30 minutes to overnight with gentle agitation. This step precipitates and fixes the proteins within the gel, removing interfering substances like SDS [8].

- Staining: Decant the fixation solution and submerge the gel in Coomassie R-250 staining solution (0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid). Agitate gently for at least 2 hours or overnight for maximum sensitivity [7] [8].

- Destaining: Transfer the gel to a destaining solution (40% methanol, 10% acetic acid). Agitate, changing the solution several times, until the gel background becomes clear and protein bands are sharply visible. To accelerate destaining, the solution can be heated to 50-60°C or an activated charcoal bag can be added to the container to absorb the dye [7] [8].

- Storage & Imaging: For long-term storage, place the gel in a 1% acetic acid solution. Capture an image using a gel documentation system with a white light source [8].

Improved Colloidal Coomassie G-250 Protocol

A modified colloidal Coomassie G-250 protocol with an added fixation step has been shown to significantly improve protein band resolution by preventing protein diffusion during washing [9]. The workflow below integrates this critical modification.

Improved Colloidal CBB-G Staining Procedure [9]:

- Fixation (Key Improvement): Immediately after electrophoresis, fix the gel in a solution of 40% methanol and 10% acetic acid for 30 minutes with agitation.

- Washing: Rinse the fixed gel with ultrapure water 3 times for 10 minutes each on a platform shaker to remove residual SDS and fixing solution.

- Colloidal Staining: Incubate the gel in colloidal CBB-G staining solution (e.g., 0.02% CBB G-250, 5% aluminium sulfate, 10% ethanol, 2% ortho-phosphoric acid) for 2 hours to overnight with shaking.

- Brief Destaining: Rinse the gel briefly with water, then wash in a destain solution (10% ethanol, 2% ortho-phosphoric acid) or simply in water for 3-5 minutes to remove colloidal particles from the gel surface.

- Imaging: The gel is now ready for imaging. Store in water.

Troubleshooting Common Staining Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Coomassie Staining

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Bands | Insufficient protein loading, over-destaining, dye depletion. | Increase protein load, shorten destaining time, use fresh staining solution [7]. |

| High Background | Incomplete destaining, residual SDS or contaminants. | Increase destaining time/time with fresh solution, ensure thorough washing steps post-electrophoresis [7]. |

| Uneven Staining | Incomplete gel immersion, inadequate agitation during staining. | Ensure the gel is fully submerged and use consistent, gentle agitation throughout [7]. |

| Protein Diffusion (Poor Resolution) | Lack of fixation prior to colloidal staining. | Incorporate a methanol/acetic acid fixation step before the washing and staining steps [9]. |

Essential Reagents and Equipment

A successful staining experiment requires more than just the dye. The following table lists key reagents and equipment necessary for performing Coomassie staining.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Coomassie Staining

| Item | Function/Description | Example Formulations / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Dye | The active staining agent. | CBB R-250 or CBB G-250 powder [7]. |

| Fixation Solution | Precipitates proteins in gel, removes interferents. | 40% Methanol, 10% Glacial Acetic Acid [7] [9]. |

| Staining Solution | Solution for incubating the gel to dye proteins. | R-250: 0.1% dye in 40% Methanol, 10% Acetic Acid. G-250 (Colloidal): 0.02% dye with aluminium sulfate, ethanol, phosphoric acid [7] [9]. |

| Destaining Solution | Removes unbound dye from the gel background. | 40% Methanol, 10% Acetic Acid (for R-250); 10% Ethanol, 2% Phosphoric Acid (for colloidal G-250) [7] [9]. |

| Washing Solution | Removes SDS and buffer salts after fixation. | 50% Methanol with 10% Acetic Acid or ultrapure water [7]. |

| Methanol & Acetic Acid | Key components of fixing, staining, and destaining solutions. | Handle with appropriate personal protective equipment in a well-ventilated area [7]. |

| Staining Trays | Container to hold gel and staining solutions. | Made of glass, plastic, or stainless steel; must be inert and large enough for the gel [7]. |

| Orbital Shaker | Provides gentle, consistent agitation. | Ensures even staining and destaining [7]. |

| Gel Documentation System | For capturing high-quality images of stained gels. | System with a high-resolution camera and white light transilluminator [7] [11]. |

Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining remains an indispensable tool in the protein scientist's toolkit. Its position is secured by a combination of robust performance, straightforward protocol, and excellent compatibility with downstream applications like mass spectrometry [7].

The choice between Coomassie variants and alternative stains ultimately depends on the experimental priorities. Coomassie R-250 offers a straightforward and economical solution for abundant protein. Colloidal Coomassie G-250 provides a superior balance of sensitivity and low background for most routine research needs. When ultimate sensitivity is required for detecting low-abundance proteins, silver or fluorescent stains are necessary, despite their higher cost and complexity [10] [12]. As with any analytical method, understanding the principles, capabilities, and limitations of Coomassie staining is key to leveraging its power effectively in research and development.

In the field of proteomics and biomedical research, the visualization of proteins separated by gel electrophoresis is a fundamental step. Among the various techniques available, silver staining stands out for its exceptional sensitivity, enabling the detection of low-abundance proteins that are often critical for understanding disease mechanisms and developing new therapeutics. This guide provides an objective comparison of silver staining against other common protein staining methods, focusing on performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and compatibility with downstream applications to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The need for high-sensitivity detection is driven by the vast dynamic range of protein concentrations in biological samples. For instance, blood samples can contain over 10,000 distinct proteins, with clinically significant biomarkers often present at concentrations ranging from picograms to low nanograms per milliliter [15]. In this context, silver staining provides a critical advantage by detecting proteins at concentrations 20-200 times lower than conventional Coomassie blue staining, enabling researchers to visualize proteins present at levels as low as 0.1-0.5 ng per band [16] [15].

Performance Comparison of Protein Staining Methods

The selection of an appropriate protein staining method requires careful consideration of sensitivity, dynamic range, protocol complexity, and compatibility with downstream analyses. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major staining methods:

Table 1: Comparison of major protein staining methods

| Staining Method | Detection Sensitivity | Dynamic Range | Protocol Time | MS Compatibility | Primary Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver Stain | 0.1-0.5 ng [16] [15] | Narrow [15] | 30-120 min [16] | Specialized protocols required [15] | Highest sensitivity; cost-effective [15] | Complex protocol; background staining issues [15] |

| SYPRO Ruby | Similar to silver stain [17] | Broad linear range [17] | ~60 min [16] | High compatibility [17] [16] | Excellent peptide recovery; broad dynamic range [17] | Requires fluorescence imaging equipment [16] |

| Coomassie Blue | 5-25 ng [16] | Limited [17] | 10-135 min [16] | High compatibility [16] | Simple protocol; reversible staining [16] | Low sensitivity [17] [16] |

| Zinc Stain | 0.25-0.5 ng [16] | N/A | ~15 min [16] | High compatibility [16] | Rapid; no protein modification [16] | Stains background, not proteins [16] |

| Fluorescent Stains | 0.25-0.5 ng [16] | Broad linear range [16] | ~60 min [16] | Generally compatible [16] | Broad dynamic range; low detection limits [16] | Requires specific imaging instruments [16] |

Silver Staining in Method Comparisons

Studies directly comparing staining methods have demonstrated that silver staining remains the most sensitive colorimetric method available. In proteomic research focused on discovering differentially expressed proteins, silver stain has shown superior detection capabilities for low-abundance targets compared to Coomassie blue, though it traditionally suffered from poor peptide recovery for mass spectrometry analysis unless extra destaining and washing steps were incorporated [17].

When compared with fluorescent staining options like SYPRO Ruby, silver staining offers similar sensitivity but differs significantly in other characteristics. SYPRO Ruby provides enhanced recovery of peptides from in-gel digests for mass spectrometry analysis and features a broad linear dynamic range, making it more suitable for rigorous quantification of protein differences [17]. However, silver staining maintains an advantage in laboratories without access to fluorescence imaging instrumentation.

Recent technological developments have introduced innovative approaches to enhance sensitivity beyond traditional methods. For example, combining carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) labeling with stain-free gel technology has demonstrated sensitivity similar to silver staining while maintaining mass spectrometry compatibility [18]. This method resulted in a 10–100-fold increase in sensitivity over Coomassie staining and standard stain-free methods [18].

Silver Staining Experimental Protocol

Detailed Methodology

Silver staining involves a multi-step process that requires precision in reagent preparation and timing. The following workflow outlines the key stages:

Diagram 1: Silver staining workflow

The fixation step immobilizes protein bands while removing interfering substances such as SDS, buffers, and salts that can cause background staining [15]. Sensitization with sodium thiosulfate significantly boosts the efficiency, sensitivity, and contrast of the staining results [15]. During silver impregnation, silver ions bind strongly to specific protein functional groups including carboxylic acid groups (aspartate and glutamate), imidazoles (histidine), sulfhydryls (cysteine), and amines (lysine) [15].

The development process reduces protein-bound ionic silver (Ag+) to metallic silver (Ag) by formaldehyde, creating dark brown or black bands at protein locations [15]. Color variation in the resulting bands is primarily attributable to the diffractive scattering caused by silver grains of differing sizes [15].

Mass Spectrometry Compatibility

A critical consideration for proteomic applications is the compatibility of silver staining with mass spectrometry analysis. Traditional silver staining protocols that use glutaraldehyde or formaldehyde during fixation and sensitization are incompatible with mass spectrometry because these reagents cause permanent protein modifications through cross-linking, particularly with lysine residues [15]. This alteration hampers trypsin digestion, resulting in restricted peptide mass fingerprint analysis and reduced sequence coverage [15].

For mass spectrometry compatibility, specialized silver staining protocols must be employed that:

- Omit glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde, substituting tetrathionate and thiosulfate for sensitization [15]

- Include thorough destaining of protein spots or bands before digestion protocols [15]

- Utilize commercial kits specifically designed for mass spectrometry compatibility that provide higher loading capacity without saturation [15]

Studies have demonstrated that tryptic digests of proteins visualized by modified silver stains without aldehydes afford excellent mass spectra by both matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization and tandem electrospray ionization [15].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful silver staining requires specific high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details essential components and their functions:

Table 2: Essential reagents for silver staining

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Silver Nitrate | Source of silver ions that bind to protein functional groups [15] | 0.1% concentration recommended for 0.5-3 mm gels; corrosive and causes skin staining [15] |

| Formaldehyde | Reducing agent that converts ionic silver to metallic silver during development [15] | Potential irritant and carcinogen; handle in fume hood [15] |

| Sodium Thiosulfate | Sensitizing agent that improves staining efficiency and contrast [15] | Critical for controlling background staining [15] |

| Sodium Carbonate | Creates alkaline environment for development process [15] | Concentration affects development rate and background [15] |

| Acetic Acid | Acidifying agent for fixation and stop solutions [15] | Flammable and corrosive; use in well-ventilated areas [15] |

| Methanol | Component of fixation solution to immobilize proteins [15] | Helps remove interfering substances from gel [15] |

| High-Purity Water | Solvent for all reagents and washing steps [15] | Essential for minimizing background staining; trace impurities cause artifacts [15] |

Technical Considerations and Challenges

Optimization Strategies

Several factors significantly impact silver staining results and require careful optimization:

Temperature Control: The protocol is temperature-dependent, with higher room temperatures (over 30°C) contributing to increased background staining [15]. Consistent temperature maintenance throughout the procedure is crucial for reproducible results.

Gel Thickness: Silver nitrate concentration of 0.1% is recommended for gels measuring between 0.5 and 3 mm in thickness, with higher concentrations needed for ultrathin gels to account for diffusion during the gel-formation process [15].

Timing Precision: Development time must be carefully monitored as the extent of staining is influenced by duration of exposure to the developer [15]. This is particularly important because silver staining is not an endpoint procedure, and significant inter-gel variations in spot intensities may occur with minor timing differences [15].

Equipment Cleanliness: Impeccably clean glassware and equipment are essential to avoid contamination that leads to background artifacts [15]. Silver mirrors (uniform surface staining) frequently result from unclean glassware or contaminated reagents [15].

Limitations and Alternative Approaches

Despite its superior sensitivity, silver staining presents several limitations that researchers should consider:

Quantification Challenges: Due to its narrow dynamic range, silver staining is not considered reliable for protein quantification [15]. The technique exhibits differential staining properties toward various proteins, making quantitative comparisons problematic.

Background Staining: Susceptibility to erratic background staining is a frequent challenge [15]. This can be mitigated by using high-purity water and reagents, maintaining optimal temperature conditions, and ensuring impeccable cleanliness of all equipment [15].

Protocol Complexity: Silver staining necessitates the preparation of various reagents and multiple precise steps, making it more labor-intensive and time-consuming than many alternative methods [16].

For applications requiring both high sensitivity and downstream protein identification, fluorescent stains like SYPRO Ruby offer a compelling alternative with broad linear dynamic range and enhanced recovery of peptides for mass spectrometry analysis [17]. Similarly, zinc staining provides rapid results (approximately 15 minutes) with sensitivity comparable to silver staining while maintaining full compatibility with mass spectrometry and western blotting [16].

Silver staining remains a powerful technique for detecting low-abundance proteins in electrophoretic separations, offering unmatched sensitivity among colorimetric detection methods. Its utility is particularly evident in initial screening applications where target proteins are present in very low quantities or when advanced instrumentation for fluorescence detection is unavailable.

However, the method demands meticulous technique and careful optimization to overcome challenges related to background staining, reproducibility, and compatibility with downstream analyses. Researchers must weigh the exceptional sensitivity of silver staining against its technical demands and limitations when selecting the most appropriate detection method for their specific application.

For proteomic studies involving protein identification, modified silver staining protocols that avoid aldehyde-based cross-linking or alternative high-sensitivity fluorescent stains may provide more practical solutions that balance detection sensitivity with analytical flexibility.

Fluorescent staining is a cornerstone technique in biomedical research and diagnostics, enabling the visualization and quantification of proteins and other biomolecules. The performance of these techniques is primarily governed by two critical parameters: sensitivity (the ability to detect low-abundance targets) and dynamic range (the ability to quantify targets across a wide concentration spectrum simultaneously). For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate staining method is crucial for obtaining accurate, reproducible, and biologically relevant data.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of major fluorescent staining methodologies, focusing on their sensitivity and dynamic range characteristics. It also details experimental protocols and highlights emerging technologies that are pushing the boundaries of what is detectable and quantifiable in complex biological systems. The content is framed within the broader thesis that understanding the efficiency and limitations of each method is essential for advancing research in proteomics, biomarker discovery, and diagnostic assay development.

Comparison of Fluorescent Staining Methods

The landscape of fluorescent stains is diverse, ranging from traditional fluorescent antibodies to advanced signal amplification techniques and novel nanomaterials. The table below provides a comparative overview of key methodologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fluorescent Staining Methods

| Method | Mechanism | Key Advantages | Limitations | Reported Sensitivity / Dynamic Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Immunofluorescence (IF) [19] | Fluorophore-conjugated antibodies bind directly to target antigens. | Simple protocol, suitable for multiplexing. | Limited sensitivity, prone to photobleaching. | Moderate sensitivity and dynamic range. |

| Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) [20] | Enzyme-mediated deposition of numerous fluorescent tyramide molecules at the target site. | High signal amplification, superior sensitivity, stable signals. | Requires optimization; potential for high background if not controlled. | >6x signal intensity; ~3x broader dynamic range vs. conventional IF. |

| Fluorescent Carbon Dots (CDs) [21] | Engineered nanoparticles that target specific organelles or molecules. | Excellent photostability, high biocompatibility, tunable emission. | Relatively new technology; synthesis parameters influence performance. | High photostability enables long-term, real-time monitoring. |

| Total Protein Stains [1] | Non-specific binding to proteins in gels (e.g., Coomassie, fluorescent stains). | Normalization for heterogeneous samples; detects protein integrity. | Not target-specific; used for gel-based analysis. | More reliable for normalization than single housekeeping proteins. |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors [22] | FRET-based conformational changes in response to target activity (e.g., PTEN). | Enables live-cell, real-time imaging of protein activity in vivo. | Complex development and implementation; requires genetic manipulation. | Enables dynamic activity monitoring with subcellular resolution. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) Protocol

The TSA protocol is designed to overcome the challenge of detecting low-abundance markers on single extracellular vesicles (EVs) and cells, which offer a very small surface area for staining [20]. The following workflow and protocol detail the key steps.

Figure 1: TSA Experimental Workflow

Experimental Protocol [20]:

- Sample Preparation and Fixation: Fix cells or tissue sections using appropriate methods (e.g., formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) sections).

- Antigen Retrieval: Perform heat-induced epitope retrieval using a solution like Cell Conditioning Solution 1.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Incubate the sample with a target-specific primary antibody (e.g., anti-A2B5, anti-CD11c) for 1 hour at room temperature.

- HRP-Conjugated Secondary Antibody: Incubate with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour.

- Tyramide Probe Incubation: Apply a fluorescently labeled tyramide reagent (e.g., Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 Tyramide) for 10 minutes. The HRP enzyme catalyzes the conversion of the tyramide into a highly reactive, short-lived radical that covalently binds to electron-rich tyrosine residues on and around the target protein.

- Counterstaining and Mounting: Counterstain with DAPI for nuclei visualization, then mount the slides for imaging.

Key Advantage: A single HRP molecule can activate hundreds of tyramide molecules, leading to significant signal amplification rather than a one-to-one antibody-fluorophore ratio [20].

High Dynamic Range (HDR) Fluorescence Imaging Protocol

A major limitation in fluorescence microscopy is the limited dynamic range of the detection system, which can cause signal saturation and loss of quantitative data. The HDR imaging protocol addresses this by combining multi-exposure capture with computational processing [23].

Experimental Protocol [23]:

- Staining and Sample Prep: Perform standard IF staining (e.g., for PD-L1 in NSCLC tissue) using either direct fluorophore-conjugated antibodies or the TSA method.

- Multi-Exposure Image Acquisition: Capture multiple images of the exact same field of view at different exposure times. For example, for an Alexa Fluor 555 signal, acquire images at 6.5 ms, 25 ms, and 55 ms. This ensures that dim signals are captured at long exposures without saturating bright areas in shorter exposures.

- HDR Algorithm Processing:

- Image Preprocessing: Apply erosion and Gaussian blurring to the original image set.

- Irradiance Curve Reconstruction: The HDR algorithm reconstructs the camera's response curve using pixel information from areas with significant signal (e.g., near nuclei for PD-L1).

- Image Merging and Scaling: The multiple exposures are merged into a single, high-bit-depth image that is linearly scaled.

- Post-Processing: The merged image undergoes luminance adjustment, contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization, and further contrast enhancement to produce the final HDR image.

- Validation: This method has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy to 85.7% in PD-L1 assessment and revealed a 25% change in tumor proportion score at various depths within 3D tumor models [23].

Optimizing Combined-Segments Strategy for Ultra-Wide Concentration Range

For quantitative fluorescence measurements in solution (e.g., in environmental or clinical diagnostics), maintaining sensitivity across an ultra-wide concentration range is a known challenge. The "optimizing combined-segments strategy" is a solution that moves beyond simple binary segmentation [24].

Experimental Protocol [24]:

- Spatial Intensity Modeling: Utilize a fluorescence spatial intensity distribution model that accounts for the attenuation of excitation light across the sample.

- Probe Positioning: Systematically adjust the position of the optical fiber receiving probe within the sample cuvette to define different fluorescence reception ranges.

- Generate Quantitative Curves: For each probe position, generate a quantitative relationship curve between the received fluorescence intensity and the fluorophore concentration (e.g., tryptophan from 0.02 to 250 mg/L).

- Segment Combination and Optimization: Instead of relying on a single curve, strategically combine segments from multiple curves. The combination is optimized to ensure that the measurement sensitivity on every adopted segment exceeds a predefined optimal sensitivity limit (

lmopt). - Outcome: This approach can maintain relative errors within ±5% across a concentration range 20 times broader than the conventional linear range, enabling high-sensitivity measurements without sample dilution [24].

Emerging Materials and Future Directions

Fluorescent Carbon Dots (CDs)

Fluorescent Carbon Dots (CDs) are emerging as superior nanoprobes that transcend the limitations of traditional organic dyes and semiconductor quantum dots. They are defined by their excellent photostability, which prevents photobleaching during long-term imaging; superior biocompatibility and low phototoxicity; and tunable fluorescence properties achieved through heteroatom doping (e.g., with nitrogen or sulfur) [21]. Their efficacy is influenced by core crystallinity, surface functional groups, size, and charge. CDs have been successfully applied for live-cell organelle staining and in vivo imaging, providing new opportunities for understanding dynamic cellular mechanisms [21].

Genetically Encoded FRET Biosensors

For monitoring dynamic protein activity (as opposed to static localization), genetically encoded biosensors represent a powerful approach. A recent advance is a FRET-based biosensor for the tumor suppressor PTEN, used with two-photon fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (2pFLIM) [22].

Figure 2: PTEN FRET Biosensor Mechanism

Mechanism: The biosensor is engineered by tagging the N and C termini of PTEN with donor (mEGFP) and acceptor (sREACh) fluorescent proteins. PTEN undergoes a conformational change from a closed/inactive state to an open/active state. In the closed state, the fluorophores are close, resulting in high FRET and a short fluorescence lifetime. Upon activation, the protein opens, increasing the distance between fluorophores, decreasing FRET, and resulting in a longer fluorescence lifetime [22]. This allows direct, real-time monitoring of PTEN activity in live cells and intact tissues, such as the mouse brain.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents is fundamental to the success of any fluorescent staining experiment. The following table details key solutions used in the methodologies discussed in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Advanced Fluorescent Staining

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Features & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tyramide Reagents [20] | Signal amplification for low-abundance targets. | Alexa Fluor Tyramide (e.g., AF488, AF594); activated by HRP to bind covalently to proteins. |

| Fluorescent Carbon Dots (CDs) [21] | Photostable, biocompatible nanoprobes for live-cell imaging. | Tunable emission; can be synthesized from natural precursors; target-specific via surface functionalization. |

| Total Protein Stains [1] | Loading control for heterogeneous samples in gel electrophoresis. | Superior to single housekeeping proteins (e.g., GAPDH) for normalization in Western blotting. |

| FRET/FLIM Biosensors [22] | Live-cell, dynamic imaging of protein activity and conformation. | Genetically encoded; e.g., PTEN biosensor with mEGFP donor and sREACh acceptor for 2pFLIM. |

| HDR Imaging Software [23] | Expands dynamic range of fluorescence microscopes post-acquisition. | Algorithms that merge multiple exposures to restore accurate expression patterns in saturated images. |

| Primary Antibodies | Target-specific recognition. | Clone-specific for antigens (e.g., PD-L1 clone SP263); critical for both IHC and IF. |

| HRP-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies [20] [23] | Enzyme-linked detection for amplification methods. | Enables TSA reaction; poly-HRP conjugates offer further signal enhancement. |

| 14S(15R)-EET methyl ester | 14S(15R)-EET methyl ester, MF:C21H34O3, MW:334.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 7-O-Methyl-6-Prenylnaringenin | 7-O-Methyl-6-Prenylnaringenin, MF:C21H22O5, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In the field of proteomics, protein gel staining is an indispensable technique that enables researchers to visualize proteins separated by electrophoresis, facilitating analysis of protein expression, purity, and interactions. The ideal staining method combines high sensitivity, broad dynamic range, operational simplicity, and compatibility with downstream protein analysis techniques, particularly mass spectrometry (MS). Among the various available methods, zinc staining has emerged as a powerful reverse staining technique that offers unique advantages for contemporary proteomic research. This review objectively compares the performance of zinc-based reverse staining with alternative methods, providing experimental data and detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting the most appropriate technique for their specific applications.

Performance Comparison of Protein Staining Methods

Technical Characteristics and Experimental Performance

The performance characteristics of major protein staining methods have been systematically evaluated in multiple studies, revealing significant differences in sensitivity, dynamic range, and compatibility with downstream applications.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Major Protein Staining Methods [25] [16]

| Staining Method | Sensitivity | Typical Protocol Time | Detection Mechanism | MS Compatibility | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc Reverse Stain | 0.25-1.8 ng | 15 minutes | Visual (reverse staining) | Excellent | No protein modification; rapid procedure |

| Silver Stain | 0.25-0.5 ng | 30-120 minutes | Colorimetric (chemical development) | Variable (formulation-dependent) | Highest sensitivity of colorimetric methods |

| SYPRO Ruby | 0.25-0.5 ng | 60 minutes | Fluorescent | Excellent | Broad linear dynamic range |

| Coomassie Blue | 5-25 ng | 10-135 minutes | Colorimetric (dye binding) | Excellent | Simple protocol; reversible staining |

A comprehensive evaluation of imidazole-zinc reverse stain demonstrated its capability to detect as few as 1.8 ng of protein in a gel, surpassing the sensitivity of conventional silver staining and SYPRO Ruby under specific conditions [25]. The linear dynamic range of zinc staining extends to revealing proteins up to 140 ng, with insignificant staining preference based on protein composition [25]. This uniform detection response across different protein types is particularly valuable for quantitative proteomic applications where staining bias could compromise results.

Methodological Workflows and Procedural Requirements

The operational workflows for different staining methods vary significantly in complexity, time requirement, and technical demands.

Diagram 1: Zinc reverse staining workflow for mass spectrometry compatibility.

Zinc staining employs a fundamentally different detection mechanism compared to conventional methods. Instead of staining proteins directly, this procedure uses zinc ions that complex with imidazole to form a milky-white precipitate throughout the polyacrylamide gel background except in regions containing SDS-coated proteins [16]. The result is clear protein bands against an opaque background, achievable in approximately 15 minutes without fixation steps [16]. This rapid, simple process requires minimal hands-on time and no specialized equipment beyond standard laboratory apparatus.

In contrast, silver staining involves multiple precise steps including fixation, sensitization, silver impregnation, and development, typically requiring 30-120 minutes with careful timing to prevent over-development [16]. The complexity of silver staining introduces greater inter-experimental variability, while the chemical modifications it imposes on proteins can interfere with subsequent mass spectrometric analysis [16].

Experimental Data and Validation

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Comparative studies have generated robust quantitative data regarding the performance of zinc staining relative to alternative methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Comparative Studies [25] [16]

| Performance Metric | Zinc Stain | Silver Stain | SYPRO Ruby | Coomassie Blue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Detectable Protein | 1.8 ng | 0.5 ng | 0.5 ng | 25 ng |

| Optimal Protein Detection Range | Up to 140 ng | Up to 20 ng | Up to 100 ng | Up to 500 ng |

| MS Identification Success Rate | ~67% | 30-50% (formulation-dependent) | ~60% | ~70% |

| Dynamic Range Linearity | Excellent | Moderate | Excellent | Good |

In one comprehensive evaluation, zinc staining demonstrated equivalent or better MS compatibility than silver, SYPRO Ruby, and Coomassie Blue staining methods [25]. Intense and comprehensive MS profiles were frequently observed for zinc-stained gel spots, with approximately two-thirds successfully identified for protein identities [25]. This high success rate in protein identification underscores the minimal protein modification characteristic of the zinc reverse stain process.

Method-Specific Protocols

Detailed Zinc Reverse Staining Protocol

The imidazole-zinc reverse staining protocol can be completed in three straightforward steps [16] [26]:

Post-Electrophoresis Processing: Following SDS-PAGE, immerse the gel in a solution of 100-200 mM imidazole with gentle agitation for 5-8 minutes. The optimal concentration depends on gel thickness and polyacrylamide percentage.

Zinc Development: Briefly rinse the gel with deionized water (approximately 15-20 seconds) before transferring to a 100-200 mM zinc sulfate solution. Observe the development of a milky-white background precipitate within 30-60 seconds. Continue agitation until the desired contrast between protein bands and background is achieved.

Visualization and Documentation: Place the stained gel on a dark background for optimal visualization of clear protein bands against the opaque gel matrix. For permanent documentation, use transparency scanning to capture even, high-contrast gel images [25]. For downstream MS analysis, excise protein bands of interest and destain by rinsing with chelating agents such as EDTA or Tris-glycine buffer.

Alternative Staining Protocols

Silver Staining Protocol [16]: Silver staining requires multiple precise steps: (1) gel fixation in 50% methanol/10% acetic acid for 30 minutes; (2) sensitization with sodium thiosulfate (0.02% w/v) for 1-2 minutes; (3) silver impregnation with silver nitrate (0.1-0.2% w/v) for 20-30 minutes; (4) image development with formaldehyde (2-3% v/v) in carbonate buffer until desired intensity; (5) termination with EDTA or citric acid solution. The extensive processing time and potential for protein cross-linking represent significant limitations for high-throughput proteomics.

SYPRO Ruby Staining Protocol [16]: SYPRO Ruby staining involves: (1) gel fixation in 50% methanol/10% acetic acid for 30 minutes; (2) staining with SYPRO Ruby dye for 3-4 hours; (3) destaining in 10% methanol/7% acetic acid for 30 minutes. While offering excellent sensitivity and MS compatibility, the extended staining time and specialized imaging equipment requirements increase operational complexity.

Research Reagent Solutions for Zinc Staining

Successful implementation of zinc reverse staining requires several key reagents, each serving specific functions in the staining process.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Zinc Reverse Staining [16] [26]

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imidazole | Forms complex with zinc ions | 100-200 mM | pH ~7.0, prepared in deionized water |

| Zinc Sulfate | Precipitates with imidazole in gel background | 100-200 mM | Concentration affects precipitate density |

| EDTA or Tris-Glycine Buffer | Destaining for band excision | 50-100 mM | Chelates zinc for MS compatibility |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Protein separation matrix | Varies by application | Standard SDS-PAGE gels compatible |

Applications in Proteomic Workflows

Integration with Downstream Analyses

The compatibility of zinc staining with mass spectrometry represents one of its most significant advantages. Unlike silver staining, which can cause protein cross-linking through aldehyde-based sensitizers, zinc staining involves no permanent chemical modification of proteins [16]. This preservation of protein integrity enables efficient tryptic digestion and peptide extraction for MS analysis. Research demonstrates that zinc-stained proteins consistently yield high-quality mass spectra with comprehensive peptide coverage [25].

For western blotting applications, zinc staining offers the unique advantage of reversible staining. Proteins can be visualized, documented, and subsequently completely destained before electroblotting, eliminating the potential interference associated with conventional stains [16]. This reversibility provides researchers with unprecedented flexibility in experimental design.

Data Analysis Considerations

The analysis of zinc-stained 2D gel images requires specific software considerations. Comparative studies indicate that Melanie 4 software is particularly suitable for analyzing zinc-stained 2D gels, which typically feature an apparent but even background [25]. The software's background subtraction algorithms effectively handle the characteristic reverse staining pattern, enabling accurate spot detection and quantification.

Diagram 2: Proteomic workflow integrating zinc staining with mass spectrometry.

Zinc reverse staining represents a compelling alternative to traditional protein staining methods, particularly for researchers engaged in high-throughput proteomics requiring downstream mass spectrometric analysis. Its exceptional speed (approximately 15 minutes), sensitivity (detecting as little as 0.25-1.8 ng protein), and excellent MS compatibility (~67% identification success rate) position it as a versatile tool for modern protein research [25] [16]. While silver staining retains advantages in ultimate sensitivity for detecting extremely low-abundance proteins, and Coomassie staining offers simplicity for routine applications, zinc staining provides an optimal balance of performance characteristics for most proteomic workflows. As the field continues to emphasize rapid, reproducible, and multi-modal protein analysis, zinc-based reverse staining is poised to play an increasingly important role in the researcher's toolkit.

Protein gel staining is a foundational technique in molecular biology and biochemistry, enabling the visualization of proteins after separation by electrophoresis. The fundamental principle involves a chemical reaction between a stain and proteins within the gel matrix, rendering them visible against the background. These stains are selected based on their specific binding to proteins and their ability to generate a detectable signal, such as color, fluorescence, or precipitation. The evolution of various staining methods has been driven by the continuous pursuit of improved sensitivity, compatibility with downstream applications, and operational ease. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance characteristics of major protein staining solutions, focusing on their quantitative detection limits, dynamic range, and procedural requirements to inform researchers in selecting the optimal method for their specific applications. The critical importance of sensitive detection is underscored in advanced applications like super-resolution microscopy, where quantifying binder labeling efficiency at the single-protein level is essential for accurate data interpretation [27].

Comparative Performance Data of Staining Methods

The selection of a protein staining method is often a trade-off between sensitivity, ease of use, cost, and compatibility with downstream analyses. The table below provides a structured comparison of the key performance metrics for the most common protein staining techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Protein Staining Methods

| Staining Method | Detection Limit (per band) | Dynamic Range | Compatibility with Downstream Applications | Typical Procedure Time | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Staining | 8-25 ng [28] | ~1 order of magnitude | High (MS, Sequencing, WB) [28] | 10-135 minutes [28] | Simple, affordable, reversible, non-destructive [28] | Lower sensitivity, protein composition bias [28] |

| Silver Staining | 0.25-0.5 ng [28] | ~2 orders of magnitude | Low (Protein cross-linking) [28] | Several hours [28] | Extremely high sensitivity [28] | Multiple complex steps, reagent sensitivity, potential cross-linking [28] |

| Fluorescent Staining | 0.25-0.5 ng [28] | >3 orders of magnitude [29] | High (MS, WB) [28] | ~60 minutes [28] | High sensitivity, broad linear range, multiplexing potential [28] [29] | Requires specialized imaging equipment [28] |

| Zinc Staining | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Fast, reversible [28] | Information missing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Coomassie Brilliant Blue Staining

The Coomassie staining protocol is renowned for its simplicity and reliability, providing a robust method for detecting protein bands in the nanogram range [28].

- Water Wash: Following electrophoresis, the gel is initially rinsed with deionized water to remove residual SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate), which can interfere with dye binding [28].

- Fixing: The gel is immersed in an acidic solution, typically containing methanol and acetic acid (e.g., 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid). This step precipitates the proteins within the gel matrix, preventing diffusion and preparing the gel for optimal dye binding. Fixing times vary but often last 30-60 minutes [28].

- Staining: The fixed gel is transferred to a Coomassie dye solution (e.g., 0.1% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in 40% methanol and 10% acetic acid). The gel is incubated with gentle agitation for at least one hour. During this time, the dye binds non-covalently to basic (arginine, lysine, histidine) and hydrophobic amino acid residues in the proteins, changing color from reddish-brown to intense blue [28].

- Destaining: Excess, unbound dye is removed through a destaining process. This involves multiple washes with a destaining solution (e.g., 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid) or simply water. This step is crucial for clearing the background and achieving sharp, visible protein bands. Destaining can be accelerated by including a kimwipe or other absorbent material in the container to trap the eluted dye [28].

Silver Staining

Silver staining is a multi-step, highly sensitive procedure for detecting proteins at sub-nanogram levels. Precise reagent handling and timing are critical for success [28].

- Sensitization: The gel is treated with a sensitizing agent, such as thiourea or formaldehyde, to enhance the subsequent binding of silver ions to protein functional groups. This step increases the overall sensitivity and uniformity of the stain [28].

- Staining: The sensitized gel is incubated with a silver nitrate solution (e.g., 0.1-0.2%). Silver ions bind to various protein side chains, including carboxylic acids (aspartic acid, glutamic acid), imidazoles (histidine), sulfhydryls (cysteine), and amines (lysine) [28].

- Development: The gel is transferred to a developing solution containing a reducing agent (e.g., formaldehyde in an alkaline carbonate solution). This step reduces the bound silver ions to metallic silver, forming a visible brown-black precipitate at the locations of the protein bands. Development is closely monitored and halted before the background becomes unacceptably dark [28].

- Stopping the Reaction: The development process is terminated by replacing the developer with a stopping solution, typically containing 1-5% acetic acid. This stabilizes the stained image [28].

Fluorescent Dye Staining

Fluorescent staining offers a sensitive and quantitative alternative to colorimetric methods, with a broad dynamic range [28] [29].

- Dye Selection: A fluorescent dye, such as SYPRO Ruby, is selected based on the required sensitivity, gel type, and available imaging equipment with appropriate excitation/emission filters [28].

- Staining: The gel is incubated in the fluorescent dye solution with gentle agitation, typically for 60-90 minutes. The dye binds to proteins through non-covalent interactions, such as electrostatic and hydrophobic binding [28].

- Washing: After staining, the gel is rinsed in a wash solution (often a dilute acetic acid and methanol solution or water) for 20-30 minutes to remove unbound dye and reduce background fluorescence [28].

- Imaging: The stained gel is visualized using a fluorescence scanner, UV transilluminator, or a compatible imaging system. The excitation and emission wavelengths are set according to the dye's specifications [28].

Workflow and Data Normalization

The experimental workflow for protein staining and analysis extends beyond the staining procedure itself. A critical path that includes proper sample preparation, quality control, and data normalization is essential for generating high-quality, reproducible quantitative data [29]. Total protein staining is increasingly recognized as a superior loading control for normalization, especially when working with heterogeneous samples, as it circumvents the variability often associated with single housekeeping proteins like GAPDH or β-tubulin [1].

Diagram 1: Protein staining and analysis workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful protein detection and quantification rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured staining protocols.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Protein Staining Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue Dyes (G-250/R-250) | Anionic triphenylmethane dyes that bind basic/hydrophobic protein residues, causing a color shift to blue [28]. | General protein detection in SDS-PAGE gels [28]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Source of silver ions that bind protein functional groups; reduced to metallic silver for visualization [28]. | High-sensitivity silver staining [28]. |

| SYPRO Ruby / Orange | Fluorescent dyes that bind proteins non-covalently, enabling high-sensitivity detection with broad dynamic range [28]. | Fluorescent western blotting, quantitative proteomics [28] [29]. |

| Imidazole-Zinc Solutions | Stains gel background; zinc ions form white precipitate with imidazole, making protein bands visible as clear areas [28]. | Fast, reversible protein staining [28]. |

| Methanol-Acetic Acid Solutions | Used for fixing (precipitating proteins) and destaining (removing unbound dye) in Coomassie protocols [28]. | Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining [28]. |

| Primary & Secondary Antibodies | Primary antibodies bind specific target proteins; enzyme- or fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies enable detection [29]. | Western blotting, super-resolution microscopy [27] [29]. |

| Total Protein Stain | A stain (e.g., fluorescent dye) that labels all proteins in a sample lane, used for normalization instead of single housekeeping proteins [1]. | Loading control for quantitative Western blotting of heterogeneous samples [1]. |

| Myricetin-3-O-rutinoside | Myricetin-3-O-rutinoside, CAS:41093-68-9, MF:C27H30O17, MW:626.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Desacetylxanthanol | Desacetylxanthanol, MF:C15H22O3, MW:250.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Considerations and Technological Outlook

The field of protein detection and analysis is continuously evolving. A significant challenge in advanced techniques like super-resolution microscopy is the absolute quantification of labeling efficiency, which is rarely 100% due to factors like limited binder affinity and steric hindrance [27]. Novel methods are being developed to address this, using reference tags and DNA-barcoded imaging to correlate target locations and precisely quantify efficiency at the single-protein level, which is crucial for accurate data interpretation [27].

Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence is poised to revolutionize reagent design. Computational models are now being developed to predict antibody structures and binding strength with high accuracy from amino acid sequences. These tools, such as the AbMap model, allow researchers to screen millions of potential antibody variants in silico to identify high-affinity binders early in the development process, potentially streamlining the creation of more effective detection reagents for research and therapeutics [30].

Methodology in Action: Selecting and Applying Stains for Your Research Goals

The selection of an appropriate protein detection method is a critical step in biomedical research and diagnostic development, directly impacting data reliability, reproducibility, and experimental efficiency. Within the broader context of comparing protein staining method efficiencies, this guide provides an objective analysis of contemporary techniques—from traditional stains to advanced automated immunoassays and mass spectrometry. The expanding proteomics pipeline and increasing emphasis on reproducible, quantitative data necessitate informed method selection based on rigorous performance characteristics. This guide synthesizes experimental data and comparative studies to equip researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based selection criteria tailored to specific application requirements across western blotting, mass spectrometry, and diagnostic workflows.

Quantitative Comparison of Protein Detection Methods

The performance characteristics of protein detection methods vary significantly across sensitivity, dynamic range, reproducibility, and throughput. The following tables synthesize key quantitative data to facilitate direct comparison.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Gel and Membrane Stains

| Stain/Method | Detection Sensitivity | Linear Dynamic Range | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ponceau S | ~200 ng [31] | Not specified | Fast (5-10 min), reversible, compatible with subsequent WB [31] | Lower sensitivity, not for low-abundance proteins [31] |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue | ~50 ng [31] | More linear at low pH [32] | High sensitivity for visible stain, cost-effective [31] | Destructive; fixes proteins, preventing transfer/WB [31] |

| SYPRO Ruby | Comparable to silver stain [17] | Broad linear dynamic range [17] | Excellent for MS; enhanced peptide recovery vs. silver stain [17] | Requires fluorescent imaging equipment [17] |

| Silver Stain | High (sub-nanogram) [17] | Limited dynamic range [17] | Very high sensitivity | Poor peptide recovery for MS; multiple extra steps needed [17] |

Table 2: Performance of Immunodetection and Targeted Quantification Methods

| Method | Reproducibility (CV) | Throughput & Hands-on Time | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Western Blot | High variability common [33] | 1-3 days; high hands-on time [33] | Widely accessible, provides molecular weight data [34] | Affected by antibody quality, low reproducibility [34] [33] |

| Automated WB (Jess Simple Western) | CV < 25% [35] | Faster; minimal hands-on time [33] [36] | High sensitivity (4000x > WB/MS), minimal sample [35] | High instrument cost, specialized reagents [33] [37] |

| Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) | CV < 8% [35] | Medium throughput after assay development | High specificity, multiplexing, absolute quantification [34] | Requires expensive instrumentation, expert operation [35] [34] |

Method Selection Guidelines for Specific Applications

Western Blotting and Immunodetection

For routine protein confirmation where molecular weight information is critical, traditional western blotting remains a benchmark. However, its limitations in quantification are well-documented [34]. When analyzing low-abundance proteins or working with minute sample amounts (e.g., patient biopsies), Simple-Western is the superior choice, offering up to 4,000-fold greater sensitivity than traditional western blot or mass spectrometry [35]. For laboratories prioritizing throughput and reproducibility over absolute lowest cost, semi-automated systems like the iBind Flex reduce hands-on time and reagent volumes, though they require higher antibody concentrations [33] [36].

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics

In biomarker discovery and quantitative proteomics, mass spectrometry methods are increasingly the gold standard. Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) provides exceptional reproducibility (CV < 8%), multiplexing capability, and absolute quantification using isotopically labeled standards [34]. For protein visualization prior to MS identification, SYPRO Ruby is highly recommended over silver stain due to its broad linear dynamic range and superior recovery of peptides for mass profiling [17].

Diagnostic Applications

The western blotting market for diagnostics is growing rapidly (7.48% CAGR), driven by the need to confirm protein expression in therapeutic monitoring and rare diseases [37]. In regulated diagnostic environments, reproducibility is paramount. Here, automated platforms that minimize user variability and targeted MS methods with high specificity are advantageous. The trend is toward validated, kit-based blot assays to reduce development timelines and ensure regulatory compliance [37].

Total Protein Normalization and Quality Control

For assessing protein transfer efficiency and total protein loading in western blots, Ponceau S staining is the most practical choice. It is rapid, reversible, and does not interfere with subsequent immunoblotting [31]. When higher sensitivity is required for total protein visualization in gels, Coomassie Brilliant Blue is effective, though it is incompatible with further western analysis [31].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Protocol 1: Traditional Western Blot with Ponceau S Quality Control

This standard protocol includes a critical quality control step to confirm efficient protein transfer.

- Sample Preparation and Separation: Lyse cells in RIPA buffer (e.g., 4°C, 30 min), clear debris by centrifugation (2000× g, 5 min), and quantify protein concentration using a BCA assay. Dilute 1-10 µg of total protein in Laemmli sample buffer, denature, and load onto a 4-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gel for electrophoresis [33] [36].

- Transfer and Staining: Electrophoretically transfer proteins to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. Briefly rinse the membrane in deionized water and incubate in Ponceau S staining solution for 5-10 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation [31].

- Visualization and Destaining: Wash the membrane in deionized water for 1-5 minutes until red protein bands are visible. Photograph the stained membrane for a permanent record. Destain completely by rinsing with several washes of TBST for 5 minutes before proceeding to immunoblotting [31].

- Immunoblotting: Block the membrane with 5% BSA in TBST. Incubate with primary antibody (diluted in blocking buffer) overnight at 4°C. Wash membrane 4 times in TBST, then incubate with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature. Wash again and detect using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) substrate [33] [36].

Protocol 2: Protein Staining for Mass Spectrometry Compatibility

This protocol optimizes protein detection for subsequent mass spectrometry analysis.

- Gel Electrophoresis and Staining: Separate proteins by 1D or 2D gel electrophoresis. After electrophoresis, carefully remove the gel and wash it three times with deionized water. Cover the gel with SYPRO Ruby Protein Gel Stain and incubate with gentle agitation for several hours to overnight, depending on gel thickness [17].

- Destaining and Imaging: Pour off the stain and rinse the gel briefly with deionized water. Destain by incubating the gel in a solution of 10% methanol and 7% acetic acid for 30-60 minutes. Image the gel using a UV or laser-based gel documentation system with the appropriate fluorescence emission filters [17].

- In-Gel Digestion: Excise protein spots/bands of interest from the gel. Subject the gel pieces to standard in-gel digestion protocols (e.g., reduction, alkylation, tryptic digestion). The use of SYPRO Ruby, as opposed to silver stain, minimizes the need for extra destaining steps and enhances peptide recovery for MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry [17].

Visual Workflows for Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting an appropriate protein detection method based on key experimental goals.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the protein detection methods discussed in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protein Detection Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ponceau S Stain | Rapid, reversible total protein stain for membranes. | Used for verifying transfer efficiency before immunoblotting; non-toxic and does not interfere with antibodies [31]. |

| SYPRO Ruby Stain | Fluorescent stain for proteins in gels. | Ideal for proteomics; offers high sensitivity and broad linear dynamic range with excellent MS compatibility [17]. |

| Pre-cast Gradient Gels | Matrix for protein separation by molecular weight. | Improve reproducibility and convenience in SDS-PAGE (e.g., 4-20% gels) [33]. |

| Validated Primary Antibodies | Specific recognition of target protein antigen. | Critical for Western blot specificity; batch-to-batch variability is a major reproducibility concern [34] [37]. |

| HRP-Conjugated Secondary Antibodies | Enzyme-linked detection of primary antibodies. | Used with ECL substrates for chemiluminescent detection in Western blotting [33]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Peptides | Internal standards for absolute quantification. | Essential for SRM mass spectrometry, allowing precise measurement of protein concentration [34]. |

| Microfluidic Capillaries & Cards | Miniaturized platforms for automated immunoassays. | Enable automated Western blotting (JESS) and semi-automated immunodetection (iBind), reducing reagent use and variability [33] [37]. |