Protein Purity Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide to SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for assessing protein purity, quality, and functionality through electrophoretic techniques.

Protein Purity Assessment: A Comprehensive Guide to SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for assessing protein purity, quality, and functionality through electrophoretic techniques. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting protocols, and validation strategies, we compare SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE to help professionals select the optimal approach for their specific research goals—whether determining molecular weight, studying native protein complexes, or ensuring sample integrity for downstream applications.

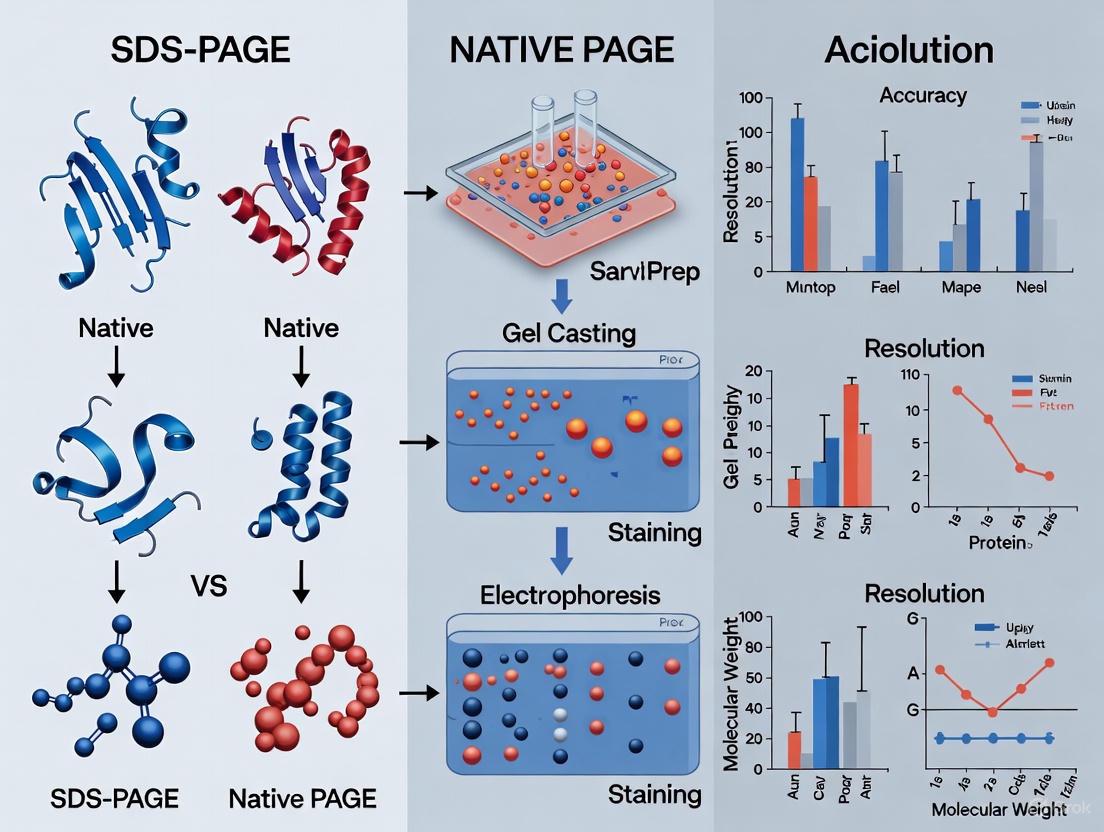

Understanding PAGE Fundamentals: How SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE Work

Core Principles of Protein Separation by Electrophoresis

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) is a foundational technique in biochemistry and molecular biology laboratories for separating protein mixtures based on their physical properties [1]. The method utilizes a gel matrix created from polymerized acrylamide, which acts as a molecular sieve [2]. Under the influence of an electric field, charged protein molecules migrate through this porous network at different rates, enabling their separation [3]. The polyacrylamide gel's pore size can be precisely controlled by adjusting the concentrations of acrylamide and bisacrylamide, allowing researchers to tailor the separation for specific protein size ranges [2] [3].

Two principal variants of this technique—SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE—have become standard tools for protein analysis, each with distinct mechanisms and applications [1] [4]. While SDS-PAGE denatures proteins to separate them primarily by molecular weight, Native PAGE maintains proteins in their native, folded state, preserving their biological activity and enabling separation based on charge, size, and shape [5]. The choice between these methods is crucial and depends directly on the research objectives, particularly in the context of assessing protein purity, structure, and function [1].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

SDS-PAGE: Separation by Molecular Weight

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) operates on the principle of denaturing proteins to separate them exclusively by their molecular mass [6] [2]. The anionic detergent SDS plays a pivotal role by binding to hydrophobic regions of proteins at a nearly constant ratio of 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein [2]. This binding achieves two critical functions: it linearizes the proteins by disrupting hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonds, and it coats them with a uniform negative charge [6] [2]. This process masks the proteins' intrinsic charges, resulting in a consistent charge-to-mass ratio across all polypeptides [1] [3]. Consequently, when an electric field is applied, all SDS-bound proteins migrate toward the anode, with smaller proteins moving faster through the gel matrix than larger ones [6] [3].

The gel structure in SDS-PAGE is typically discontinuous, consisting of two distinct parts: a stacking gel and a separating gel [2]. The stacking gel, with a lower acrylamide concentration (4-5%) and pH (~6.8), concentrates the protein samples into sharp, thin bands before they enter the separating gel [2]. The separating gel has a higher acrylamide concentration (often 7.5%-20%) and pH (~8.8), which provides the resolving power to separate proteins based on size [2]. Sample preparation is a key denaturing step; proteins are heated to 70-100°C in a buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol (DTT), which breaks disulfide bonds to ensure complete denaturation into polypeptide subunits [6] [2] [3].

Native PAGE: Separation by Charge, Size, and Shape

In contrast to the denaturing approach of SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE (also known as non-denaturing PAGE) separates proteins in their native, folded conformation without the use of denaturing agents [1] [4]. This technique preserves the protein's higher-order structure, including secondary, tertiary, and quaternary architectures, as well as any bound cofactors [1] [3]. Since SDS is absent, proteins are not uniformly charged; instead, they retain their intrinsic charge, which is determined by their amino acid composition and the pH of the running buffer [4] [5].

In Native PAGE, separation depends on a combination of the protein's net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [1] [3]. Proteins with higher negative charge density migrate faster toward the anode, while the gel matrix creates a sieving effect that retards larger or more structurally complex proteins more than smaller, compact ones [3]. This multi-parameter separation means that a protein's migration rate is not directly proportional to its molecular weight, making Native PAGE unsuitable for precise molecular weight determination [1]. However, it is exceptionally valuable for studying functional properties, as proteins frequently retain their enzymatic activity and protein-protein interactions throughout the electrophoresis process and can be recovered in an active state for downstream applications [1] [4].

Table 1: Core Principles of SDS-PAGE versus Native PAGE

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight (mass) of polypeptide subunits [4] [2] | Native size, net charge, and 3D shape [1] [3] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [6] [2] | Native, folded conformation [1] [4] |

| Key Reagent | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate), an anionic detergent [6] [2] | No denaturing agents; may use Coomassie dye (BN-PAGE) [7] [4] |

| Charge | Uniform negative charge from SDS binding [6] [3] | Intrinsic charge of the protein [4] [5] |

| Sample Prep | Heating with SDS and reducing agents [4] [2] | No heating; no denaturing/reducing agents [4] |

| Functional Activity | Destroyed [1] [7] | Preserved [1] [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol outlines a standard denaturing SDS-PAGE procedure for analyzing protein samples based on molecular weight [6] [2].

Sample Preparation:

- Dilution: Dilute the protein sample in an appropriate buffer.

- Mixing with Loading Buffer: Mix the protein solution with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli sample buffer. A standard 1X final concentration contains: 1% (w/v) SDS, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.02% (w/v) bromophenol blue, and 50 mM DTT or 5% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol as a reducing agent in Tris buffer at pH ~6.8 [6] [2].

- Denaturation: Heat the mixture at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and reduction of disulfide bonds [2] [3].

- Centrifugation: Briefly centrifuge the samples to collect condensation.

Gel Preparation:

- Resolving Gel: First, prepare and cast the resolving gel. For a 10% gel, a typical formulation includes: 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), acrylamide/bis-acrylamide solution (30% acrylamide, 0.8% bis), 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 0.1% (w/v) ammonium persulfate (APS), and 0.05% (v/v) TEMED [3]. Pour the solution between glass plates, leaving space for the stacking gel. Carefully overlay with isopropanol or water to ensure a flat interface.

- Polymerization: Allow the resolving gel to polymerize completely (approximately 15-30 minutes).

- Stacking Gel: After polymerization of the resolving gel, prepare the stacking gel solution containing: 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), a lower percentage of acrylamide (e.g., 4-5%), 0.1% SDS, 0.1% APS, and TEMED. Pour off the overlay, add the stacking gel solution, and immediately insert a well-forming comb [2] [3].

- Final Setup: Once polymerized, remove the comb and place the gel cassette into the electrophoresis chamber.

Electrophoresis:

- Buffer Preparation: Fill the inner and outer chambers with running buffer, typically Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, pH ~8.3) [2].

- Loading: Load the prepared protein samples and molecular weight markers into the wells.

- Running Conditions: Apply a constant voltage of 100-150 V for a mini-gel. Run until the bromophenol blue tracking dye reaches the bottom of the gel (typically 40-60 minutes) [6].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Visualization: After electrophoresis, proteins are visualized using stains like Coomassie Brilliant Blue (detection limit ~100 ng) or more sensitive silver stain (detection limit ~1 ng) [6] [2].

- Western Blotting: For immunodetection, proteins can be transferred from the gel onto a membrane for western blotting [1] [6].

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

This protocol describes a basic Native PAGE procedure for separating proteins while maintaining their native structure and function [4] [3].

Sample Preparation:

- Non-Denaturing Buffer: Dilute the protein sample in a non-denaturing buffer compatible with protein stability, such as 20-50 mM Tris-Cl or Bis-Tris at a neutral pH [7].

- No Denaturants: Crucially, the sample buffer must not contain SDS, reducing agents, or other denaturants.

- No Heating: The sample is not heated prior to loading [4].

- Additives: Glycerol (5-10%) may be added to increase sample density for easier loading, and a tracking dye like bromophenol blue can be included [7].

Gel Preparation:

- Gel Composition: Cast a polyacrylamide gel without SDS or other denaturants. The acrylamide concentration is chosen based on the target protein size, similar to SDS-PAGE.

- Buffer System: The gel and running buffers are typically at a neutral or slightly basic pH (e.g., 7.2-8.0) to maintain protein stability and native charge [7] [3]. Tris-Glycine or Tris-Borate are common choices.

- Blue Native (BN)-PAGE Variant: For difficult-to-separate complexes like membrane proteins, Coomassie G-250 dye can be added to the cathode buffer and sample. The dye binds to proteins, imparting a negative charge and improving solubility and resolution without full denaturation [7].

Electrophoresis:

- Running Conditions: Load the native samples and run the gel. To minimize heat-induced denaturation, electrophoresis is often performed at 4°C [4].

- Buffer Polarity: Verify the polarity of the electrodes based on the net charge of your proteins at the running buffer's pH. For most proteins at basic pH, the net charge is negative, so they will migrate toward the anode [3].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Visualization: Standard protein stains (Coomassie, Silver) are used.

- Functional Assays: Since functionality is retained, proteins can be eluted from the gel for activity assays, or activity stains can be performed directly on the gel [1] [3].

Comparative Analysis for Protein Purity Assessment

Performance in Purity Evaluation

Assessing protein purity is a critical step in protein research and biopharmaceutical development. SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE offer complementary perspectives, each with distinct strengths and limitations for this application [1].

SDS-PAGE for Purity Analysis: SDS-PAGE is the most commonly used method for assessing the purity of a protein sample [2]. By denaturing the protein into its constituent polypeptides, it reveals the number and size of different polypeptide chains present. A pure, single-subunit protein will appear as a single, sharp band on the gel, while the presence of additional bands indicates contaminating proteins or protein fragments [2]. This technique is highly effective at identifying non-covalently bound impurities, as the denaturing conditions will dissociate them. However, SDS-PAGE cannot distinguish between a pure sample of a single protein and a mixture of different proteins that happen to have identical molecular weights. Furthermore, it provides no information about whether the protein is properly folded or functionally active [1].

Native PAGE for Purity Analysis: Native PAGE provides a different kind of purity assessment by separating proteins based on their native charge and size [1]. It is particularly valuable for detecting inactive or misfolded protein variants that may have a different surface charge or conformation than the active protein, even if their molecular weight is identical. This makes it ideal for assessing the homogeneity of a protein preparation in its functional form [3]. For multi-subunit complexes, Native PAGE can analyze the integrity and stoichiometry of the complex, which is destroyed in SDS-PAGE [3]. A single band in Native PAGE suggests a homogeneous population of proteins with identical charge and conformation. The key advantage is that the protein can often be recovered in an active state from the gel for further functional studies [1] [4].

Supporting Experimental Data and Applications

The practical differences between these techniques are underscored by experimental data. A study focusing on metalloproteins demonstrated that while standard SDS-PAGE resulted in a near-total loss (only 26% retention) of bound zinc ions, a modified Native SDS-PAGE protocol preserved 98% of the metal ions [7]. Furthermore, enzymatic activity assays showed that all nine model enzymes were inactive after standard SDS-PAGE, but seven of the nine retained their activity when subjected to Native SDS-PAGE, with all nine remaining active in BN-PAGE [7].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis for Protein Purity and Characterization

| Aspect | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Purity Indicator | Single band suggests a single polypeptide species [2]. | Single band suggests a homogeneous native conformation [1]. |

| Detects Contaminants | Effective for contaminants of different molecular weight [2]. | Effective for contaminants with different charge or conformation [1]. |

| Multi-Subunit Complexes | Dissociates complexes; shows individual subunits [2] [3]. | Preserves intact complexes; assesses quaternary structure [3]. |

| Functional Correlation | Poor; denatured proteins are inactive [1] [7]. | High; proteins often retain function [1] [3]. |

| Key Applications | - Molecular weight determination [6] [2]- Assessing polypeptide purity [2]- Western blotting [1] [6] | - Studying oligomerization state [1]- Analyzing protein-protein interactions [1]- Purification of active proteins [3] |

| Quantitative Data (from [7]) | - Zn²⺠retention: ~26% [7]- Enzyme activity: Denatured/Destroyed [7] | - Zn²⺠retention: Up to 98% [7]- Enzyme activity: Preserved in 7/9 model enzymes [7] |

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful electrophoresis relies on a set of essential reagents, each serving a specific function in the separation process.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide / Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polymer matrix of the gel, creating a porous sieve for separation [2] [3]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | (SDS-PAGE only) Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [6] [2]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Provides the buffering system for maintaining the correct pH during gel polymerization and electrophoresis [2] [3]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalysts for the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide into a gel [2] [3]. |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | (SDS-PAGE only) Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds to ensure complete protein denaturation [6] [2]. |

| Glycine | Component of the running buffer; its ion mobility creates the discontinuous buffer system for effective stacking [2]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue / Silver Stain | Dyes used to visualize separated protein bands after electrophoresis [6] [2]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A mixture of proteins of known sizes run alongside samples to estimate molecular weights [2] [3]. |

| Coomassie G-250 | (BN-PAGE only) Binds to proteins superficially, providing charge for electrophoresis without full denaturation [7]. |

SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE are indispensable yet complementary tools in the protein scientist's arsenal. SDS-PAGE excels in providing high-resolution separation based purely on molecular weight, making it ideal for determining subunit size, assessing polypeptide purity, and preparing samples for western blotting [1] [2]. In contrast, Native PAGE separates proteins based on a combination of their native charge, size, and shape, thereby preserving protein complexes, enzymatic activity, and functional states [1] [3].

The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but is dictated by the specific research question. For a broad assessment of polypeptide composition and molecular weight, SDS-PAGE is the standard workhorse. When the goal is to probe functional integrity, study protein-protein interactions, or characterize native complexes, Native PAGE is the unequivocal method of choice [1]. A comprehensive strategy for assessing protein purity often involves employing both techniques to gain a complete picture of both compositional homogeneity (via SDS-PAGE) and conformational/functional integrity (via Native PAGE).

In the field of protein analysis, the assessment of protein purity is a fundamental task. Two primary electrophoretic techniques, SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE, serve as cornerstone methods for this purpose, yet they operate on opposing principles. SDS-PAGE employs denaturing conditions to dismantle protein structures, providing a precise measure of molecular weight and subunit composition. In contrast, Native PAGE preserves the protein's native, functional state to study activity and complex formation. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, framing them within the context of protein purity assessment for researchers and drug development professionals.

Principles of Protein Separation: A Tale of Two Techniques

SDS-PAGE: Denaturation for Molecular Weight Determination

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is an analytical technique designed to separate proteins based almost exclusively on their molecular weight. [2] This is achieved through a deliberate denaturation process. The anionic detergent SDS binds uniformly to polypeptide chains at a ratio of approximately 1.4 grams of SDS per gram of protein, linearizing the proteins by disrupting hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and ionic bonds. [2] This binding confers a uniform negative charge density, masking the protein's intrinsic charge and ensuring that migration through the polyacrylamide gel matrix is determined solely by polypeptide chain length. [1] [4] The process typically includes a reducing agent, such as dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol, to break disulfide bonds, ensuring complete denaturation into individual subunits. [2] The gel itself consists of two distinct regions: a stacking gel (pH ~6.8) that concentrates proteins into sharp bands, and a separating gel (pH ~8.8) where size-based separation occurs, with smaller proteins migrating faster than larger ones. [2]

Native PAGE: Preserving Native Structure and Function

Native PAGE (Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis) separates proteins under non-denaturing conditions, maintaining their folded conformation, biological activity, and interactions with cofactors. [1] [4] In this method, SDS is absent, and samples are not heated. [4] Consequently, separation depends on a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and shape. [4] This technique is ideal for studying functional properties, such as enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and oligomeric state composition. [1] [7] Because it preserves functionality, proteins separated via Native PAGE can often be recovered in an active form for downstream assays. [1] [4] Variants like Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) use Coomassie dye to impart charge for separation, while Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) relies on the protein's inherent charge in a gradient gel. [4]

Comparative Analysis: Technique Selection for Research Goals

The choice between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE is dictated by the specific research objectives. The table below summarizes the core differences to guide method selection.

Table 1: Key Technical and Application Differences Between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight (size) only [4] [2] | Molecular size, intrinsic charge, and shape [4] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [1] [2] | Native, folded conformation [1] [4] |

| SDS Presence | Present in sample and running buffers [4] | Absent [4] |

| Reducing Agent | Present (e.g., DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) [4] [2] | Absent [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated (typically 85-100°C) [4] [8] | Not heated [4] [8] |

| Net Protein Charge | Uniformly negative [1] [2] | Positive, negative, or neutral (based on native charge) [4] |

| Functional Recovery | Proteins lose function; cannot be recovered post-separation [1] [4] | Proteins retain function; can be recovered post-separation [1] [4] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight estimation, purity assessment, subunit composition, western blotting [1] [4] [2] | Studying protein structure, oligomerization, enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions [1] [4] [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Protein Purity Assessment

Denaturing SDS-PAGE Protocol

The following protocol is adapted from standard procedures for pre-cast Tris-Glycine gels. [8]

Sample Preparation:

- Mix protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Tris-Glycine SDS Sample Buffer. This buffer contains SDS for denaturation and glycerol to increase sample density. [8]

- For reduced conditions, add a reducing agent like DTT to a final concentration of 1X. [8]

- Heat the sample at 85°C for 2 minutes to ensure complete denaturation. [8]

Electrophoresis:

- Load prepared samples and molecular weight standards into the wells of a pre-cast polyacrylamide gel. [8]

- Assemble the gel apparatus filled with 1X Tris-Glycine SDS Running Buffer. This buffer provides the ions necessary for the discontinuous buffer system and contains SDS to maintain protein denaturation. [8] [2]

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 125 V until the tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue) front reaches the bottom of the gel. [8]

Post-Electrophoresis:

- Proteins are visualized using stains like Coomassie Brilliant Blue or silver stain. [2]

- For western blotting, proteins are transferred to a membrane after gel separation. [1]

Non-Denaturing (Native) PAGE Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Mix protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer. This buffer lacks SDS and reducing agents. [8]

- Do not heat the sample. [4] [8]

Electrophoresis:

- Load the prepared native sample into the gel.

- Use 1X Tris-Glycine Native Running Buffer in the electrophoresis apparatus. This buffer does not contain SDS or other denaturants. [8]

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 125 V. The run time may be longer than for SDS-PAGE. [8]

Post-Electrophoresis:

- Proteins can be visualized with stains compatible with activity assays.

- For functional analysis, the gel can be used in an activity stain or specific assay to detect enzymatic function. [1] [7]

Supporting Experimental Data and Hybrid Approaches

Experimental data underscores the functional consequences of each method. A key study demonstrated that subjecting nine model enzymes to standard SDS-PAGE conditions resulted in the denaturation and complete loss of activity for all nine. [7] In contrast, all nine enzymes retained their activity when separated via BN-PAGE. [7] This starkly highlights the trade-off between resolution and functionality.

To bridge this gap, modified protocols like Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) have been developed. This method reduces the SDS concentration in the running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375%, removes EDTA from the buffers, and omits the sample heating step. [7] The results are promising: under these modified conditions, seven of the nine model enzymes, including four zinc-binding proteins, retained their activity after electrophoresis. [7] Furthermore, the retention of bound zinc ions in proteomic samples increased dramatically from 26% with standard SDS-PAGE to 98% with NSDS-PAGE, confirming the preservation of native metalloprotein structure. [7] This hybrid approach offers a path to high-resolution separation while retaining certain functional properties.

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes: Metal Retention and Enzyme Activity

| Electrophoresis Method | Zn²⺠Retention in Proteomic Samples | Enzymatic Activity Retention (Model Systems) |

|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE | 26% [7] | 0 out of 9 enzymes active [7] |

| BN-PAGE | Not explicitly stated, but method preserves native state | 9 out of 9 enzymes active [7] |

| NSDS-PAGE | 98% [7] | 7 out of 9 enzymes active [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful electrophoresis relies on a suite of specialized reagents, each with a critical function in the separation process.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins, imparts uniform negative charge. [2] | Critical for SDS-PAGE; absent in Native PAGE. [4] |

| Reducing Agent (DTT, BME) | Breaks disulfide bonds for complete denaturation. [2] | Used in reducing SDS-PAGE; omitted for non-reduced SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE. [8] |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Sieving matrix that separates proteins based on size. [2] | Pore size is adjusted via acrylamide concentration. [2] |

| Tris-Glycine Running Buffer | Provides ions for conductivity and establishes pH for separation. [8] [2] | SDS-containing vs. Native formulations are not interchangeable. [8] |

| Coomassie Blue / Silver Stain | Binds to proteins for visual detection post-electrophoresis. [2] | Silver staining is more sensitive than Coomassie Blue. [2] |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Proteins of known size for molecular weight calibration. [2] | Essential for accurate molecular weight estimation in SDS-PAGE. [2] |

| Ptp1B-IN-25 | PTP1B Inhibitor | Ptp1B-IN-25 is a potent PTP1B inhibitor for research into type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cancer. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| (Rac)-PDE4-IN-4 | (Rac)-PDE4-IN-4|Potent PDE4 Inhibitor|RUO |

Workflow and Logical Pathway for Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making pathway for selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method based on research goals, leading to the corresponding experimental workflow.

SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE are complementary, not competing, techniques in the protein scientist's arsenal. SDS-PAGE is the unequivocal method for determining molecular weight, assessing purity, and analyzing subunit composition under denaturing conditions. Native PAGE is indispensable for probing the functional, native state of proteins, including their interactions and enzymatic activity. The emergence of modified techniques like NSDS-PAGE demonstrates ongoing innovation, offering potential pathways to reconcile high resolution with the preservation of biological function. A deep understanding of the principles and applications of both methods, as detailed in this guide, is fundamental to designing robust experimental strategies for protein purity assessment and characterization in research and drug development.

In the field of protein research, the analytical technique chosen can fundamentally shape the experimental outcomes. Within the context of assessing protein purity, the choice between Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Native PAGE represents a critical methodological crossroad. SDS-PAGE, a denaturing technique, has long been a workhorse for determining molecular weight and assessing sample homogeneity [1] [6]. In contrast, Native PAGE serves a different, equally vital purpose: it preserves the native, three-dimensional structure of proteins throughout the separation process [1] [3]. This preservation is paramount when the research objective extends beyond mere protein size to encompass the understanding of biological function, protein-protein interactions, and enzymatic activity. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate technique is not a trivial matter; it is a decisive factor that determines whether proteins are analyzed as inert chains or as dynamic, functional biological entities. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these two foundational techniques, with a focused examination of how Native PAGE enables the study of proteins in their biologically active state.

Core Principles: A Tale of Two Techniques

The fundamental difference between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE lies in their treatment of the protein's native structure. SDS-PAGE employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which denatures proteins by binding to the polypeptide backbone and masking intrinsic charges. This process unfolds proteins into linear chains, imparting a uniform negative charge that causes separation to occur almost exclusively on the basis of molecular weight [1] [6] [3]. Consequently, quaternary structures are disrupted, subunits dissociate, and biological activity is invariably lost.

Native PAGE, conversely, is a non-denaturing technique. It forgoes denaturing agents like SDS, allowing proteins to retain their folded conformation, multimeric state, and cofactors. Under these conditions, separation depends on a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and shape as it migrates through the gel matrix [1] [3] [5]. The higher the negative charge density and the smaller the size, the faster a protein will migrate. This preservation of native state is the very feature that enables the recovery of functional proteins from the gel for downstream activity assays or interaction studies [1].

Comparative Analysis: Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

The choice between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE has profound implications for the type of information that can be obtained from an experiment. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their characteristics, applications, and outcomes.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Analysis Criteria | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principle | Based on protein's intrinsic charge, size, and 3D shape [1] [3] | Based primarily on molecular weight [1] [6] |

| Gel Condition | Non-denaturing [5] [4] | Denaturing [5] [4] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation; multimeric complexes intact [1] [3] | Denatured, linearized polypeptide chains [1] [6] |

| Biological Activity | Retained post-separation [1] [7] | Destroyed [1] [7] |

| Key Reagents | Coomassie G-250 (in BN-PAGE), no SDS [7] | SDS, reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) [9] [6] |

| Sample Preparation | No heating; mild buffers [7] [4] | Often includes heating (70-100°C) in SDS-containing buffer [7] [6] |

| Typical Applications | Study of protein complexes, enzymatic activity, oligomerization [1] [3] | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment, western blotting [1] [9] |

| Protein Recovery | Functional proteins can be recovered [1] [5] | Proteins are denatured and inactive [1] |

The functional consequences of these technical differences are significant. For instance, experimental data shows that seven out of nine model enzymes, including four zinc-binding proteins, retained their activity after separation via a modified Native SDS-PAGE protocol. In contrast, all nine enzymes were denatured and inactivated during standard SDS-PAGE [7]. Furthermore, the retention of bound metal ions—critical for the function of many metalloproteins—increased from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% under native conditions [7]. This quantitative data underscores the superior capability of Native PAGE in preserving functional protein properties.

Experimental Data and Protocol

The quantitative superiority of Native PAGE for functional analysis is demonstrated in studies comparing metal retention and enzymatic activity post-electrophoresis. The following protocol and resulting data highlight the practical application of Native PAGE for researchers requiring preservation of biological activity.

Detailed Native (N)SDS-PAGE Protocol

This protocol, adapted from PMC4517606, outlines a modified approach that balances good protein resolution with the retention of native properties [7]:

- Sample Preparation: Mix 7.5 μL of protein sample (5-25 μg) with 2.5 μL of 4X NSDS sample buffer. The buffer composition is critical: 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 0.0185% (w/v) Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% (w/v) Phenol Red, pH 8.5 [7].

- Key Difference: Do not heat the samples. This is a fundamental distinction from denaturing SDS-PAGE, where heating at 70-100°C is standard practice to ensure complete denaturation [7] [6].

- Gel Preparation: Use standard precast NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris 1.0 mm mini-gels (or equivalent). Prior to sample loading, pre-run the gel at 200V for 30 minutes in double-distilled Hâ‚‚O to remove the storage buffer and any unpolymerized acrylamide [7].

- Running Buffer: Prepare the NSDS-PAGE running buffer: 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7. Note the significantly reduced SDS concentration compared to standard SDS-PAGE running buffer (0.1% SDS) [7].

- Electrophoresis: Load the prepared samples and run the gel at a constant voltage of 200V for approximately 45 minutes, or until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [7].

Quantitative Outcomes

The efficacy of this native approach is confirmed by direct comparison with standard techniques, as summarized in the table below.

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of protein function and metal retention post-electrophoresis (Data sourced from PMC4517606) [7]

| Analysis Parameter | Standard SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | Native (N)SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn²âº) Retention | 26% | Not Specified | 98% |

| Enzymatic Activity Retention | 0 out of 9 enzymes | 9 out of 9 enzymes | 7 out of 9 enzymes |

| Protein Resolution | High | Lower than SDS-PAGE | High, comparable to SDS-PAGE |

This data demonstrates that Native PAGE, and particularly the NSDS-PAGE variant, offers a compelling compromise, providing high-resolution separation while retaining a high degree of biological function and cofactor integrity. Confirmation of metal retention can be further performed using techniques like laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) or in-gel staining with metal-specific fluorophores such as TSQ [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of Native PAGE requires specific reagents designed to maintain protein structure and function. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the protocol.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for Native PAGE experimentation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Composition / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NSDS Sample Buffer | Maintains protein in native state; provides density for gel loading [7] | 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, 0.0185% Coomassie G-250, pH 8.5 [7] |

| Native Running Buffer | Conducts current while preserving weak protein interactions [7] | 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7 [7] |

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts mild negative charge for electrophoresis (in BN-PAGE); does not denature proteins [7] | Used in place of SDS in Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) |

| Pre-cast Bis-Tris Gels | Provides consistent polyacrylamide matrix for separation; Bis-Tris gels are stable over a wide pH range [7] | e.g., NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris Gels; preferred for native techniques |

| Protease Inhibitors (e.g., PMSF) | Prevents proteolytic degradation during sample prep, crucial for preserving intact protein complexes [7] | Added to cell lysis buffers |

| Glycerol | Increases density of sample for well loading; can help stabilize protein structure [7] [5] | Standard component of native sample buffers (e.g., 10% v/v) |

| Mcl-1 inhibitor 12 | Mcl-1 inhibitor 12 is a potent and selective MCL-1 blocker that induces apoptosis in cancer cells. For research use only. Not for human use. | |

| Antileishmanial agent-26 | Antileishmanial agent-26, MF:C23H27FN4O2, MW:410.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Within the broader thesis of protein purity analysis, Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE are not competing techniques but rather complementary tools that answer fundamentally different questions. SDS-PAGE excels at answering the question, "What is the size and purity of the polypeptide chains in my sample?" In contrast, Native PAGE addresses the more complex question, "What is the functional state, oligomeric composition, and interactive capacity of the native proteins in my sample?" For drug development professionals, this distinction is critical. The assessment of a therapeutic protein's activity, the characterization of a target protein complex, or the study of a metalloenzyme's function all necessitate the use of Native PAGE to obtain biologically relevant data. While SDS-PAGE remains an indispensable first step for routine purity checks and molecular weight estimation, Native PAGE provides a unique window into the dynamic, functional world of proteins as they exist in their physiological context. The choice between them should be guided by a clear understanding of the scientific question at hand, ensuring that the methodology aligns with the ultimate goal of the research.

Key Differences in Buffer Composition and Sample Preparation

In the assessment of protein purity for research and drug development, the choice of electrophoresis method is a critical decision that directly impacts experimental outcomes. SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE represent two fundamental approaches with divergent methodologies for protein separation, primarily distinguished by their buffer composition and sample preparation techniques. While SDS-PAGE denatures proteins to separate them purely by molecular weight, Native PAGE preserves protein structure and function by maintaining native conditions throughout the electrophoretic process. This comparison guide examines the key technical differences between these methods, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data necessary to select the appropriate technique for specific protein purity assessment applications.

Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

The fundamental divergence between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE begins with their underlying separation mechanisms, which dictate their respective applications in protein analysis.

In SDS-PAGE, the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) plays a pivotal role by denaturing proteins and imparting a uniform negative charge density. When proteins are heated with SDS and reducing agents, they unfold into linear polypeptides that bind SDS in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g protein) [10] [3]. This process masks the proteins' intrinsic charges and eliminates structural differences, resulting in separation based almost exclusively on molecular mass as proteins migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix [11] [3]. This denaturing approach makes SDS-PAGE particularly effective for determining molecular weight, analyzing subunit composition, and assessing protein purity in pharmaceutical development.

Conversely, Native PAGE maintains proteins in their native, folded conformation throughout the separation process [1]. Without denaturing agents, proteins retain their higher-order structure, enzymatic activity, and interactions with cofactors [4] [3]. Separation occurs based on a combination of factors including the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional structure [1] [11]. This preservation of native properties makes Native PAGE invaluable for studying functional protein complexes, oligomerization states, and protein-protein interactions in their physiological conformations [1].

Comprehensive Buffer Composition Comparison

The buffer systems for SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE differ significantly in their components and functions, reflecting their distinct approaches to protein separation.

Table 1: Comparative Buffer Compositions for SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE

| Component | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE | Functional Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergent | SDS (0.1-1%) [7] [10] | None or mild non-ionic detergents [4] | Denatures proteins & imparts uniform charge (SDS) [3] |

| Reducing Agent | DTT (40-160 mM) or β-mercaptoethanol [10] | None [4] | Reduces disulfide bonds [10] |

| Buffering Agent | Tris-HCl (50-200 mM, pH 6.8-8.7) [10] [3] | Tris-HCl/Bis-Tris (50-375 mM, pH ~7.0-8.8) [12] [13] | Maintains appropriate pH [10] |

| Chelating Agent | EDTA (1-2 mM) [10] | None [4] | Chelates divalent cations to inhibit proteases [10] |

| Tracking Dye | Bromophenol Blue [10] | Bromophenol Blue or Coomassie Blue [12] [13] | Visualizes migration progress [10] |

| Glycerol | 10-20% [10] | 10-25% [12] | Increases density for well loading [10] |

| Additional Components | - | 6-aminocaproic acid (BN-PAGE) [13] | Stabilizes protein complexes & improves resolution [13] |

SDS-PAGE buffer systems are designed for complete protein denaturation. The standard sample buffer contains SDS (0.1-1%), a reducing agent (DTT or β-mercaptoethanol), Tris-HCl buffer, EDTA, glycerol, and tracking dye [10]. The running buffer typically includes Tris, glycine, and 0.1% SDS [3]. The discontinuous buffer system creates stacking and separating phases that initially concentrate proteins before separation by size [3].

Native PAGE buffer systems avoid denaturing components. The sample buffer typically contains Tris buffer, glycerol, and tracking dye without SDS or reducing agents [12]. The running buffer consists of Tris-glycine at pH 8.3-8.8 [12]. Specialized variants like Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) incorporate Coomassie dye in the cathode buffer, which binds proteins and imparts negative charge without denaturation [13]. BN-PAGE buffers also include 6-aminocaproic acid to stabilize protein complexes and improve resolution [13].

Sample Preparation Protocols

Sample preparation methods for these techniques differ dramatically in their treatment of proteins before electrophoresis.

SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation Protocol

- Dilution: Dilute protein sample to 2 mg/mL final concentration in appropriate solvent [10]

- Buffer Addition: Mix 1:1 with 2X concentrated sample buffer (containing 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 20 mM Tris-Cl pH 6.8, 2 mM EDTA, 160 mM DTT, 0.1 mg/mL bromophenol blue) [10]

- Denaturation: Heat samples at 70-100°C for 10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [10] [3]

- Centrifugation: Briefly centrifuge at high speed (16,000 x g) to pellet any insoluble material [10]

- Loading: Load 10-20 μL per well (corresponding to 10-40 μg total protein) [10]

The heating step is critical for membrane proteins or those with extensive hydrophobic regions, as it increases molecular motion to allow SDS penetration [10]. DTT or β-mercaptoethanol reduces disulfide bonds that might resist denaturation by SDS alone [10].

Native PAGE Sample Preparation Protocol

- Preparation: Keep samples and buffers at 4°C throughout preparation to maintain protein stability [4] [12]

- Buffer Addition: Mix sample with non-denaturing sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 25% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) [12]

- No Heating: Avoid any heating of samples to prevent denaturation [4] [12]

- Loading: Load 5-20 μL immediately onto pre-cooled gel [13]

For BN-PAGE, additional steps include:

- Solubilizing mitochondrial or membrane samples with n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (2% final concentration) [13]

- Incubating on ice for 30 minutes followed by centrifugation at 72,000 x g to remove insoluble material [13]

- Adding Coomassie blue G to the supernatant before loading [13]

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Recent studies have quantified the functional outcomes of these different preparation methods, particularly regarding protein activity retention and metal cofactor preservation.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Between Electrophoresis Methods

| Performance Metric | SDS-PAGE | Native SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn²⺠Retention | 26% [7] | 98% [7] | >98% [7] |

| Enzyme Activity Retention | 0/9 model enzymes [7] | 7/9 model enzymes [7] | 9/9 model enzymes [7] |

| Protein Recovery Post-Separation | Not feasible [4] | Possible with partial function [7] | Fully functional recovery [4] |

| Resolution of Complex Mixtures | High resolution [7] [3] | High resolution [7] | Moderate resolution [7] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Accurate for polypeptides [3] | Accurate for native proteins [7] | Affected by shape & charge [1] |

A modified approach called Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) demonstrates how buffer adjustments can bridge these techniques. By reducing SDS in the running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375%, removing EDTA, and eliminating the heating step, researchers achieved 98% Zn²⺠retention compared to 26% with standard SDS-PAGE [7]. Furthermore, seven of nine model enzymes retained activity after NSDS-PAGE, while all were denatured in standard SDS-PAGE [7]. This hybrid approach maintains high resolution while preserving some native protein properties.

Electrophoresis Workflow and Experimental Design

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the key procedural differences between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE methodologies:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of either electrophoretic method requires specific reagent systems optimized for each technique's requirements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PAGE Techniques

| Reagent | Function | SDS-PAGE Specific | Native PAGE Specific |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS | Denatures proteins & imparts charge | Required [10] [3] | Not used [4] |

| DTT/β-mercaptoethanol | Reduces disulfide bonds | Required [10] | Not used [4] |

| Coomassie Blue G | Stains proteins & imparts charge (BN-PAGE) | Not used in buffers | BN-PAGE essential [13] |

| n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside | Solubilizes membrane proteins | Sometimes used | BN-PAGE essential [13] |

| 6-aminocaproic acid | Stabilizes protein complexes | Not used | BN-PAGE buffer component [13] |

| Protease inhibitors | Prevents protein degradation | Optional | Recommended [13] |

| Acrylamide/bis-acrylamide | Forms gel matrix | Standard (e.g., 12%) [7] | Gradient recommended (6-13%) [13] |

| Molecular weight markers | Size calibration | Denatured standards [3] | Native standards [13] |

Technical Considerations for Protein Purity Assessment

When assessing protein purity within research and development contexts, several technical factors must be considered:

Temperature Control: Native PAGE requires maintenance at 4°C throughout the procedure to preserve protein stability, while SDS-PAGE is typically performed at room temperature [4] [12]. For Native PAGE, placing the entire electrophoresis system on ice is recommended to prevent protein degradation during separation [12].

Gel Composition: While both techniques use polyacrylamide gels, Native PAGE often employs gradient gels (e.g., 6-13%) to resolve protein complexes of varying sizes, whereas SDS-PAGE frequently uses single-percentage gels appropriate for the target protein size range [13] [3].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Proteins separated by Native PAGE can be recovered in functional form for activity assays or interaction studies, while SDS-PAGE separated proteins are typically used for western blotting, mass spectrometry, or immunodetection after denaturation [1].

The selection between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE for protein purity assessment hinges on the specific research objectives and the nature of the information required. SDS-PAGE provides superior resolution for molecular weight determination and subunit analysis under denaturing conditions, making it ideal for routine protein characterization and purity assessment. Conversely, Native PAGE preserves native protein structure and function, enabling studies of protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional interactions. The recently developed Native SDS-PAGE offers a promising intermediate approach, maintaining high resolution while preserving some functional properties. Understanding these fundamental differences in buffer composition and sample preparation allows researchers to strategically select the most appropriate methodology for their specific protein analysis requirements in drug development and basic research applications.

In the field of protein research, the assessment of protein purity, structure, and function is a fundamental requirement, particularly for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in biopharmaceutical characterization. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a cornerstone technique for these analyses, primarily through two divergent methodological approaches: denaturing SDS-PAGE and native PAGE. These techniques operate on fundamentally different separation principles—mass versus charge-to-mass ratio—each offering distinct advantages and limitations for specific research applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform appropriate technique selection within the context of protein purity analysis and broader thesis research.

Core Principles of Separation

Separation by Mass: SDS-PAGE

Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) separates proteins primarily by molecular mass [14] [3]. This is achieved through a denaturing process where proteins are unfolded and complexed with the anionic detergent SDS. The SDS binds to the polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio (approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein), conferring a uniform negative charge density across all proteins [3]. Consequently, the intrinsic charge of any protein becomes negligible compared to the overwhelming negative charge provided by SDS, resulting in a relatively consistent charge-to-mass ratio for all protein-SDS complexes [15].

The separation mechanism relies on the sieving properties of the polyacrylamide gel matrix. When an electric field is applied, all proteins migrate toward the anode. Smaller proteins navigate the porous network more easily and migrate faster, while larger proteins are hindered and migrate more slowly [14] [3]. The gel pore size, controlled by the polyacrylamide concentration, can be optimized to resolve different molecular weight ranges [3].

Separation by Charge-to-Mass Ratio: Native PAGE

In contrast, native PAGE (or non-denaturing PAGE) separates proteins based on their intrinsic properties in the absence of denaturants [3]. Separation depends on the combined influence of the protein's net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [3]. In alkaline running buffers, most proteins carry a net negative charge and migrate toward the anode, with the migration rate proportional to their charge density (net charge per unit mass) [3]. Simultaneously, the gel matrix exerts a frictional, sieving effect that regulates movement according to the protein's size and shape [3]. Therefore, a small, highly charged protein will migrate fastest, while a large, minimally charged protein will migrate slowest.

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

| Feature | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Separation Principle | Molecular mass [14] [3] | Net charge, size, and shape (charge-to-mass ratio) [3] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [14] | Native, folded structure preserved [3] |

| Detergent | SDS present [14] | No denaturing detergents [3] |

| Charge Profile | Uniform negative charge from SDS [3] | Intrinsic net charge of the protein [3] |

| Impact on Function | Functional properties and non-covalently bound cofactors are destroyed [7] | Enzymatic activity and functional properties are often retained [7] [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Proteins are diluted in a sample buffer containing SDS (an ionic detergent) and a reducing agent (e.g., β-mercaptoethanol or dithiothreitol) [14].

- The sample is heated to 95°C for 5 minutes to denature the proteins, disrupt hydrogen bonds, and cleave disulfide bonds, fully dissociating the protein into its subunits [14] [3].

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis:

- A discontinuous gel system is typically used, comprising a stacking gel (lower % acrylamide, pH ~6.8) and a resolving gel (higher % acrylamide, pH ~8.8) [14].

- The running buffer and gel contain SDS to maintain protein denaturation and charging [14].

- Electrophoresis is performed at constant voltage (e.g., 100-200V) until the dye front reaches the gel bottom [7] [14].

Standard Native PAGE Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Proteins are prepared in a non-denaturing sample buffer that lacks SDS, reducing agents, and does not involve a heating step [7] [3].

- The buffer often contains glycerol to facilitate gel loading and a pH indicator [7].

Gel Composition and Electrophoresis:

- Gels are cast in the absence of SDS [3].

- The running buffer is a mild, non-denaturing solution (e.g., Tris-Glycine, Tris-Borate) that maintains a pH (typically alkaline) where most proteins carry a net negative charge, driving electrophoresis without denaturation [3].

- To preserve native protein structure and function, the electrophoresis apparatus is often kept cool, and pH extremes are avoided [3].

Advanced Hybrid Protocol: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

A modified technique, NSDS-PAGE, has been developed to bridge the gap between the high resolution of SDS-PAGE and the native-state preservation of BN-PAGE (Blue-Native PAGE) [7]. The protocol involves key modifications to standard SDS-PAGE:

Sample Preparation:

- SDS and EDTA are removed from the sample buffer, and the heating step is omitted [7].

- The sample buffer includes Coomassie G-250 and glycerol [7].

Electrophoresis Conditions:

- The SDS concentration in the running buffer is significantly reduced (e.g., from 0.1% to 0.0375%), and EDTA is deleted [7].

- This method demonstrated a dramatic increase in the retention of bound Zn²⺠in proteomic samples from 26% (standard SDS-PAGE) to 98%, with seven out of nine model enzymes retaining activity post-electrophoresis [7].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The choice between SDS-PAGE and native PAGE significantly impacts the outcome of an experiment and the type of information that can be obtained.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of PAGE Techniques

| Performance Characteristic | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | High resolution separation of complex protein mixtures by mass [7] | Lower resolution as a one-dimensional method compared to SDS-PAGE [7] | High resolution, similar to SDS-PAGE [7] |

| Mass Determination | Excellent, with minimal effect from protein composition [3] | Poor, due to influence of native charge and shape [7] | Not explicitly stated |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | Very low (e.g., 26% Zn²⺠retention) [7] | High (inherently preserves non-covalent interactions) [7] | Very High (e.g., 98% Zn²⺠retention) [7] |

| Enzymatic Activity Retention | Destroyed (0 out of 9 model enzymes active) [7] | Preserved (9 out of 9 model enzymes active) [7] | Largely Preserved (7 out of 9 model enzymes active) [7] |

| Quaternary Structure Analysis | No (dissociates complexes) [14] | Yes (generally retains multimeric proteins) [3] | Likely limited |

| Applications | Purity assessment, immunoblotting, mass estimation [7] [3] | Protein-protein interactions, enzyme activity assays, purification of active proteins [7] [3] | Metalloprotein analysis, functional proteomics where high resolution and activity are needed [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of electrophoretic methods requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge; essential for SDS-PAGE [14] [3]. | Monomers bind to proteins; micelles do not. A concentration > 1mM is sufficient for denaturation [14]. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked porous gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [3]. | The ratio and total concentration determine gel pore size and rigidity [3]. |

| APS & TEMED | Ammonium persulfate (APS) is a radical initiator and TEMED is a catalyst; together they trigger polymerization of the gel [14] [3]. | Freshness impacts polymerization efficiency and gel quality. |

| Reducing Agents (β-ME, DTT) | β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) or Dithiothreitol (DTT) cleave disulfide bonds to fully dissociate protein subunits [14]. | Critical for analyzing proteins with quaternary structure stabilized by disulfide bridges. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A set of proteins of known mass run alongside samples to enable estimation of protein molecular weights [3]. | Available in various size ranges; pre-stained markers allow tracking during electrophoresis. |

| Coomassie Blue | A dye used for staining proteins post-electrophoresis to visualize separated bands [14]. | Can be used in the sample buffer of NSDS-PAGE [7]. |

| Tris-based Buffers | Provide the conductive medium and maintain the pH required for electrophoresis and protein stability [14] [3]. | Different buffers (e.g., Tris-Glycine, Bis-Tris) are used for different gel chemistries and pH requirements. |

| Tegeprotafib | Tegeprotafib, MF:C13H11FN2O5S, MW:326.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AChE-IN-44 | AChE-IN-44, MF:C31H38ClN3OS2, MW:568.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Workflows and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting the appropriate electrophoresis method based on research goals, particularly in the context of assessing protein purity and quality.

Electrophoresis Method Selection Workflow. This chart guides the selection of SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE, or NSDS-PAGE based on research objectives such as mass determination, complex analysis, and functional retention.

The comparative analysis of SDS-PAGE and native PAGE reveals a fundamental trade-off in protein separation science: the high resolution and mass-based separation of SDS-PAGE comes at the cost of native protein structure and function, while native PAGE preserves activity but offers lower resolution and more complex separation parameters. The development of hybrid techniques like NSDS-PAGE demonstrates the ongoing innovation in the field to overcome these limitations. For researchers assessing protein purity, the choice is clear-cut: SDS-PAGE is the definitive tool. However, for a comprehensive thesis that extends beyond purity to encompass functional characterization, protein-protein interactions, and the analysis of metalloproteins, a combination of these techniques, selected via a logical workflow, is essential for building a complete and defensible scientific narrative.

Method Selection and Practical Applications: Choosing the Right PAGE Approach

In the realm of protein analysis, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) remains a foundational technique for determining molecular weight and assessing sample purity. This guide objectively compares its performance against a key alternative—Native PAGE—within research and biopharmaceutical contexts. While SDS-PAGE excels in denaturing separation by molecular weight, Native PAGE preserves native protein structure and function, making the choice between them application-dependent [4] [1]. Understanding their distinct capabilities, supported by experimental data, enables researchers and drug development professionals to select the optimal method for their specific purity assessment goals.

Core Principles and Comparative Workflows

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in sample treatment. SDS-PAGE uses the anionic detergent SDS to denature proteins, mask their intrinsic charge, and impart a uniform negative charge-to-mass ratio. This simplifies separation to primarily molecular weight [4] [16]. In contrast, Native PAGE employs non-denaturing conditions, separating proteins based on their combined native charge, size, and shape [4] [5].

The following diagrams illustrate the key procedural differences and logical decision-making pathway for selecting the appropriate method.

Direct Performance Comparison: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

The choice between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE involves trade-offs between resolution, structural preservation, and application suitability. The table below summarizes their core differentiating characteristics.

| Criteria | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight (mass) only [4] [16] | Native size, overall charge, and 3D shape [4] [5] |

| Gel Condition | Denaturing [4] | Non-denaturing [4] |

| Sample Preparation | Heated with SDS and reducing agents (e.g., DTT) [4] | Not heated; no denaturing/reducing agents [4] |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized [1] | Native, folded, and functional [1] |

| Protein Recovery/Function | Proteins lose function; cannot be recovered [4] | Proteins retain function; can be recovered post-separation [4] [1] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity analysis, protein expression checking [4] [9] | Studying protein complexes, oligomerization state, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions [4] [1] |

| Typical Running Temperature | Room Temperature [4] | 4°C [4] |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

Case Study 1: Analysis of PEGylated Proteins

Protein PEGylation creates a mixture of modified proteins, unmodified proteins, and free PEG, making characterization challenging. A comparative study used RP-HPLC, SE-HPLC, SDS-PAGE, and Native PAGE to analyze HSA PEGylated with different PEG sizes (5k, 10k, 20k) [17].

- SDS-PAGE Results: While capable of running all PEGylation samples, SDS-PAGE produced smeared or broadened bands, attributed to undesirable interactions between PEG and SDS. This compromised resolution and clarity [17].

- Native PAGE Results: This method eliminated the PEG-SDS interaction problem and provided better resolution for all samples. Various PEGylated products and unmodified protein migrated differentially under native conditions, making it a robust alternative for characterizing the PEGylation reaction mixture [17].

Case Study 2: Purity Analysis of Therapeutic Antibodies

Antibody purity analysis is critical in biopharmaceutical development. A direct comparison of SDS-PAGE and Capillary Electrophoresis-SDS (CE-SDS) for analyzing a normal and heat-stressed IgG sample revealed limitations of the traditional gel method [16].

Table: Quantitative Comparison of SDS-PAGE vs. CE-SDS for Antibody Purity Analysis

| Analysis Feature | SDS-PAGE | CE-SDS |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Lower resolution separation of impurities [16] | High-resolution separation, easy quantitation of degradation species [16] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Lower, making autointegration of impurity bands difficult [16] | Significantly higher [16] |

| Detection of Nonglycosylated IgG | Not resolved or detected [16] | Easily detected and quantified [16] |

| Reproducibility | Subject to staining/destaining variability and manual interpretation [16] | Excellent overall reproducibility (data from 4 consecutive runs) [16] |

| Quantitation | Semi-quantitative via band intensity [16] | Fully quantitative via UV detection [16] |

This data shows that while SDS-PAGE is useful for initial assessments, higher-resolution techniques like CE-SDS are superior for critical purity assessments in quality control, especially for detecting species like nonglycosylated antibodies which are functionally important [16].

Case Study 3: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) – A Hybrid Approach

A modified method termed NSDS-PAGE demonstrates the ongoing innovation in electrophoresis. It reduces SDS in the running buffer (to 0.0375%) and removes EDTA and the heating step from sample preparation [7].

Table: Retention of Native Properties in PAGE Methods

| Method | Protein Resolution | Enzyme Activity Retention | Metal Cofactor Retention (Zn²âº) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard SDS-PAGE | High | 0 out of 9 model enzymes [7] | 26% [7] |

| BN-PAGE | Lower than SDS-PAGE [7] | 9 out of 9 model enzymes [7] | Not Specified |

| NSDS-PAGE | High (comparable to SDS-PAGE) [7] | 7 out of 9 model enzymes [7] | 98% [7] |

This hybrid technique offers a powerful compromise, providing the high resolution of traditional SDS-PAGE while preserving most functional properties, which is particularly valuable for metalloprotein analysis [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of these techniques relies on specific reagent solutions. The following table details key materials and their functions.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling separation by mass [4] [18]. | Critical for SDS-PAGE; omitted in Native PAGE. Purity is essential for consistent results. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol) | Breaks disulfide bonds in proteins, ensuring complete unfolding and accurate molecular weight determination in reducing SDS-PAGE [4] [9]. | Omitted in non-reducing SDS-PAGE to study disulfide bridges, and in Native PAGE to preserve structure. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | Forms a porous matrix that acts as a molecular sieve. The acrylamide concentration determines pore size and resolution range [4] [9]. | Can be hand-cast or purchased as precast gels for convenience and reproducibility. Gradient gels can resolve a wider MW range. |

| Coomassie Blue Stain | A dye that binds nonspecifically to proteins, allowing visualization of separated bands after electrophoresis [9]. | Common for general protein detection. More sensitive fluorescent or silver stains are available. |

| Tris-based Running Buffer | Provides the conductive ionic medium necessary for electrophoresis and maintains a stable pH during the run [4]. | Buffer composition varies between SDS-PAGE (contains SDS) and Native PAGE (no SDS) [7]. |

| Molecular Weight Standards | A mixture of proteins of known sizes run alongside samples to estimate the molecular weight of unknown proteins [9]. | Essential for molecular weight calibration. |

| Ret-IN-25 | Ret-IN-25, MF:C22H17N3O5S, MW:435.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GLS1 Inhibitor-7 | GLS1 Inhibitor-7, MF:C20H17F3N4O3S2, MW:482.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

SDS-PAGE is an indispensable, robust tool for routine molecular weight determination and initial purity assessment, particularly when protein denaturation is acceptable or desired. However, the experimental data clearly shows that for applications requiring the preservation of native structure, activity, or complex composition—such as characterizing PEGylated proteins, active enzymes, or protein-protein interactions—Native PAGE is the superior choice [17] [1] [7]. Furthermore, for critical biopharmaceutical purity analysis, advanced capillary electrophoresis methods are increasingly outperforming traditional SDS-PAGE in resolution and quantitation [16]. A sophisticated approach to protein purity analysis involves selecting the method whose strengths are best aligned with the specific analytical question.

In the field of protein research, selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method is crucial for obtaining accurate and biologically relevant data. While SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) has become a standard workhorse in molecular biology laboratories for determining molecular weight and assessing purity, Native PAGE serves distinct purposes that are equally vital for comprehensive protein characterization. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing specifically on the applications where Native PAGE offers unique advantages, particularly in the analysis of protein complexes and functional studies.

The fundamental distinction lies in how proteins are prepared and separated. SDS-PAGE denatures proteins into linear polypeptides, masking intrinsic charges and enabling separation primarily by molecular weight [1] [2]. In contrast, Native PAGE maintains proteins in their folded, native state, allowing separation based on a combination of size, charge, and shape [1] [4]. This critical difference in approach dictates their respective applications in research and drug development.

Key Differences Between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

Table 1: Fundamental differences between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Parameter | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded structure preserved | Denatured, linearized polypeptides |

| Separation Basis | Size, intrinsic charge, and shape | Molecular weight primarily |

| Detergent Usage | No SDS or other denaturing detergents | SDS required for denaturation |

| Sample Preparation | No heating; may include protease inhibitors | Heating at 70-100°C with reducing agents |

| Protein Function Post-Separation | Retained (enzymatic activity, binding capability) | Lost due to denaturation |

| Protein Recovery | Functional proteins can be recovered | Proteins cannot be recovered in functional form |

| Primary Applications | Studying protein complexes, oligomerization, functional assays | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment, subunit analysis |

Native PAGE Methodologies and Protocols

Core Native PAGE Protocol

The fundamental Native PAGE protocol maintains proteins in their native state throughout the process. Protein samples are typically prepared in non-denaturing buffers without SDS or reducing agents [4]. The gel system lacks SDS, and samples are not heated before loading [1] [5]. Separation occurs under mild conditions, often at 4°C to further preserve protein stability [4]. The running buffer composition varies but typically includes Tris-glycine or Bis-Tris systems at neutral pH without denaturing agents [7].

Specialized Native PAGE Variants

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

BN-PAGE represents a powerful refinement of native electrophoresis for analyzing membrane protein complexes and supercomplexes. This method utilizes Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which binds to proteins and confers additional negative charge while maintaining native structure [7] [4]. The dye-protein interaction allows for improved resolution of complex mixtures while preserving protein-protein interactions. BN-PAGE has been particularly valuable in mitochondrial research and respiratory chain analysis [19].

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE)

CN-PAGE employs a charge-shift method without Coomassie blue, relying on the intrinsic charge of protein complexes for separation [4]. This approach minimizes potential interference from the dye while still maintaining native conditions, though it may offer slightly lower resolution for some protein complexes compared to BN-PAGE.

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

A hybrid approach called NSDS-PAGE demonstrates how modified conditions can preserve certain functional properties while maintaining high resolution. By reducing SDS concentration in running buffers from 0.1% to 0.0375%, eliminating EDTA, and omitting the heating step, researchers achieved 98% retention of bound Zn²⺠compared to only 26% with standard SDS-PAGE [7]. Under these conditions, seven of nine model enzymes retained activity after electrophoresis, whereas all were denatured during standard SDS-PAGE [7].

Experimental Data Supporting Native PAGE Applications

Quantitative Comparison of Complex Analysis Capabilities

Table 2: Performance comparison in protein complex analysis based on experimental data

| Analysis Parameter | Native PAGE Approaches | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Complex Preservation | Maintains quaternary structure and interactions [1] | Disassembles complexes into subunits [1] |

| Metalloprotein Metal Retention | 98% Zn²⺠retention with NSDS-PAGE [7] | 26% Zn²⺠retention [7] |

| Enzyme Activity Post-Electrophoresis | 7/9 model enzymes active with NSDS-PAGE; all active with BN-PAGE [7] | 0/9 enzymes active [7] |

| Proteomic Coverage (HBSMC) | 4,323 proteins assigned [20] | 2,552 proteins assigned [20] |

| Membrane Protein Analysis | Effective for membrane protein complexes [19] | Requires solubilization; loses native interactions |

Case Study: Complexome Profiling with CN-PAGE

Recent research demonstrates the power of Native PAGE in comprehensive complexome analysis. In a study of Arabidopsis thaliana proteins, CN-PAGE coupled with mass spectrometry enabled the identification and quantification of 2,338-2,469 proteins across biological replicates [19]. The approach showed high reproducibility with Pearson's correlation coefficients exceeding 0.9 between replicates. Notably, 89% of identified proteins peaked in fractions corresponding to size ranges larger than their monomeric masses, indicating successful preservation of protein complexes [19]. This methodology allowed researchers to track changes in protein complex abundance between different diurnal time points, revealing metabolic adaptations in plants.

Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for Native PAGE experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bis-Tris or Tris-Glycine Buffers | Maintain neutral pH for native conditions | Standard Native PAGE running buffer [7] |

| Coomassie G-250 | Imparts charge for BN-PAGE without denaturation | BN-PAGE for membrane protein complexes [7] [4] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent protein degradation during extraction | Cell lysate preparation for native analysis [21] |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for loading | Sample preparation buffer component [7] |

| Nonionic Detergents (Digitonin, DDM) | Solubilize membrane proteins gently | Membrane protein complex isolation [21] |

| Molecular Weight Standards | Native protein markers for size estimation | Calibration for native molecular weight [7] |

Workflow Comparison: Native PAGE versus SDS-PAGE

Native PAGE serves as an indispensable technique in scenarios where protein function, complex formation, or native structure are paramount. The experimental data clearly demonstrates its superiority for studying metalloprotein metal retention, enzymatic activity preservation, and protein-protein interactions. While SDS-PAGE remains the method of choice for molecular weight determination and purity assessment, Native PAGE provides complementary information that is crucial for comprehensive protein characterization.

For researchers and drug development professionals, integrating Native PAGE into analytical workflows enables the identification of native protein complexes, assessment of functional integrity, and detection of biologically relevant oligomeric states. The technique's ability to preserve protein function after separation makes it particularly valuable for downstream applications, including activity assays and complex purification. When used strategically alongside SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE provides a more complete understanding of protein systems, ultimately strengthening research outcomes and therapeutic development.

While SDS-PAGE has long been the workhorse for protein analysis in molecular weight determination and purity assessment, its denaturing nature destroys native protein structure and function [7] [1]. For researchers studying functional protein complexes, enzymatic activity, or protein-protein interactions, native electrophoresis techniques are essential. Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Clear Native (CN)-PAGE have emerged as powerful alternatives that preserve proteins in their native state, enabling the study of intact protein complexes, enzymatic function, and sophisticated structural analyses that are impossible with standard denaturing methods [22] [23].

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

Blue Native PAGE utilizes the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds to hydrophobic protein surfaces and imposes a uniform negative charge shift [22]. This charge shift forces even basic proteins to migrate toward the anode while preventing aggregation of membrane proteins during electrophoresis. The result is separation primarily based on molecular mass under native conditions [22] [24].

Clear Native PAGE represents a refinement where non-colored mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents replace Coomassie dye in the cathode buffer [25]. These mixed micelles similarly induce a charge shift to enhance protein solubility and migration while eliminating dye interference [25] [23]. High-resolution CN-PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) offers resolution comparable to BN-PAGE while being milder and better retaining labile supramolecular assemblies [25] [23].

Comparative Technical Specifications