Preserving Protein Truth: A Strategic Guide to Preventing Denaturation in Native PAGE for Functional Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on preventing protein denaturation during Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE).

Preserving Protein Truth: A Strategic Guide to Preventing Denaturation in Native PAGE for Functional Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on preventing protein denaturation during Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE). Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details methodological strategies for preserving native protein structure, quaternary complexes, and biological activity. The content explores optimized protocols for Blue-Native (BN-PAGE) and Clear-Native (CN-PAGE) electrophoresis, troubleshooting common pitfalls, and validation techniques through in-gel activity assays and comparative analyses. By synthesizing current best practices, this guide empowers scientists to obtain reliable, functionally relevant data for studying protein complexes, interactions, and metabolic diseases, ultimately enhancing the translational impact of their research.

The Native State Imperative: Understanding Protein Structure and Denaturation Threats in PAGE

Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental technique for analyzing proteins in their biologically active states. Unlike denaturing methods, Native PAGE allows researchers to separate protein complexes based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape while preserving their higher-order structures [1]. This preservation is crucial for studying protein-protein interactions, enzymatic activity, and multiprotein complexes in drug development and basic research. This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance on the principles, methodologies, and troubleshooting of Native PAGE within the critical context of preventing artificial protein denaturation during analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE?

The core difference lies in the preservation of protein structure. SDS-PAGE uses the denaturing detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and heat to unfold proteins into linear chains, destroying tertiary and quaternary structures and separating subunits based almost solely on molecular weight [1]. In contrast, Native PAGE is run in the absence of denaturing agents, allowing proteins to maintain their native conformation, charge, and subunit interactions [1]. This makes Native PAGE the preferred method for studying functional protein complexes.

2. How does Native PAGE preserve a protein's tertiary and quaternary structure?

Native PAGE preserves structure by omitting harsh reagents. The key is the use of non-denaturing, non-reducing sample buffers that do not contain SDS, urea, or reducing agents like beta-mercaptoethanol or DTT [1]. By avoiding these chemicals, the non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces) and disulfide bonds that hold a protein's three-dimensional shape and multi-subunit assemblies remain intact during the electrophoretic process.

3. Why is my protein band smeared or poorly resolved?

Band smearing in Native PAGE is a common challenge and often relates to protein denaturation or aggregation. Potential causes include:

- Denaturation at Air-Water Interfaces: Simply pipetting or vortexing a protein sample can introduce air bubbles, creating air-water interfaces where proteins can adsorb and partially unfold [2].

- Protein Instability: The protein complex may be inherently unstable in the electrophoresis buffer conditions (e.g., incorrect pH, salt concentration).

- Overloading: Loading too much protein can overwhelm the gel matrix, leading to poor separation and smearing.

- Incorrect Gel Percentage: Using a gel pore size that is not optimal for the size of the native protein complex can result in poor resolution.

4. Can I determine molecular weight accurately with Native PAGE?

No, accurate molecular weight determination is a key limitation of Native PAGE. A protein's migration depends on its size, its inherent charge, and its shape [1]. Since different proteins have different charge densities and shapes, they will migrate at different rates even if they are the same size. For molecular weight determination, SDS-PAGE is the appropriate technique [1].

Troubleshooting Guide

The following table outlines common issues, their probable causes, and solutions focused on preventing denaturation.

| Problem | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared Bands | Protein denaturation/aggregation at air-water interfaces [2]. | Avoid foaming during sample preparation. Use additives like 5-10% glycerol or sucrose to stabilize proteins. |

| Protein instability in buffer. | Optimize buffer pH and salt composition. Include stabilizing cofactors (e.g., Mg²âº, Ca²âº). | |

| No Bands or Faint Bands | Loss of protein activity/structure. | Ensure the running buffer and gel are kept cold (4°C) during electrophoresis to maintain stability. |

| Protein has migrated in the wrong direction. | Check the native charge (pI) of your protein versus the buffer pH; a positively charged protein will migrate towards the cathode. | |

| Poor Separation Resolution | Inappropriate gel pore size. | Use gradient gels or optimize the acrylamide percentage for your target protein complex size. |

| Incomplete entry into the gel. | Use a low-percentage stacking gel to pre-concentrate the proteins before separation. |

Experimental Protocol: Standard Native PAGE

This protocol is designed to minimize the risk of protein denaturation during analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Native PAGE |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the porous gel matrix for size-based separation. |

| Non-denaturing Detergent (e.g., Digitonin) | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving some protein-protein interactions. |

| Glycerol/Sucrose | Increases sample density for gel loading and can help stabilize protein structure. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye used in "Blue Native PAGE" to impart charge and color to proteins for visualization. |

| Pluronic F-127 Thermal Gel | A temperature-responsive polymer used as a matrix to control separation viscosity and improve resolution [3]. |

| Tris-Glycine or Tris-Bicine Buffer | Provides the pH and ion environment for electrophoresis and protein stability. |

Methodology

- Gel Casting: Prepare a non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-20% gradient). Do not add SDS to any gel or buffer solutions.

- Sample Preparation: Mix the protein sample with a non-denaturing loading buffer. Crucially, do not boil the sample. Simply mix and centrifuge briefly. Avoid vigorous pipetting to prevent introducing air bubbles [2].

- Electrophoresis: Load the samples and run the gel in a cold room (4°C) or using a cooling apparatus. Use a constant voltage as recommended for your specific setup. The running buffer must also be free of SDS and reducing agents.

- Detection: After electrophoresis, proteins can be visualized using Coomassie staining, or if fluorescently labeled, imaged directly.

Native PAGE Workflow and Separation Mechanism

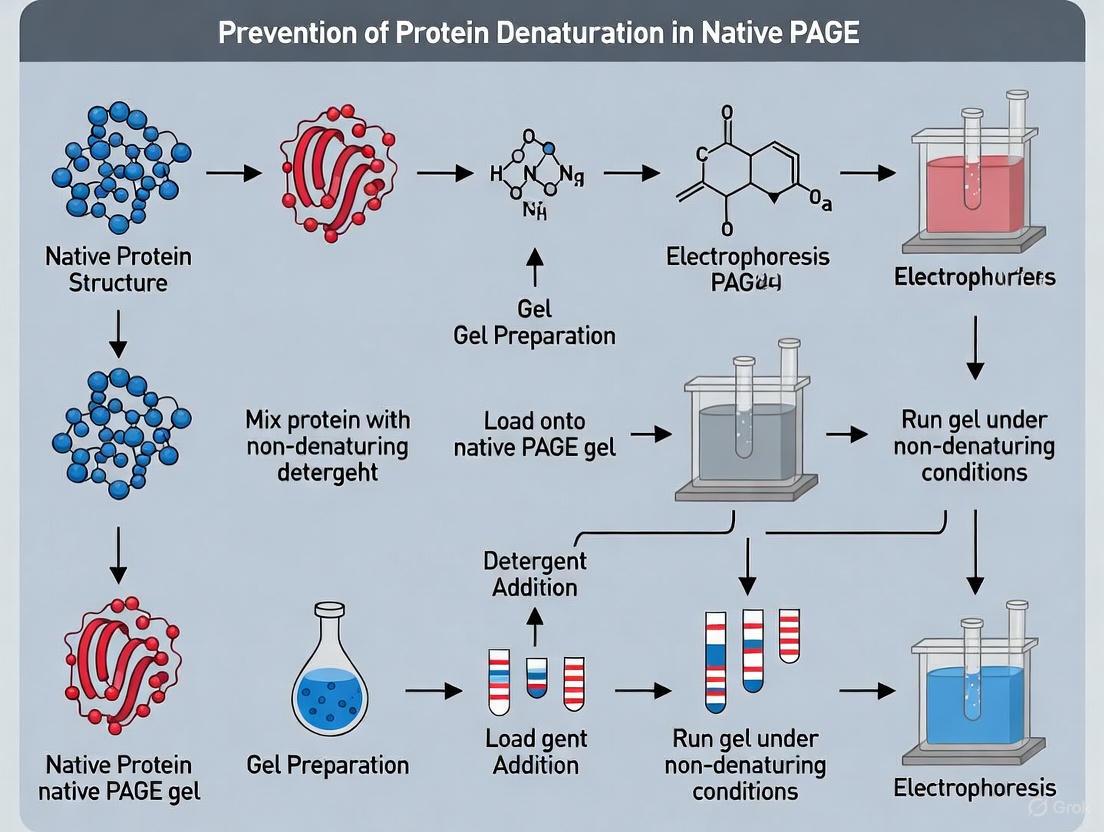

The following diagram illustrates the critical steps where protein structure is preserved, from sample preparation to separation.

Mechanism of Native PAGE Separation

This diagram contrasts the principles of Native PAGE with denaturing SDS-PAGE to highlight how structure is preserved.

In native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE), the ultimate goal is to separate protein complexes while preserving their delicate higher-order structures, functional activities, and intricate interactions. This stands in direct contrast to denaturing SDS-PAGE, where proteins are deliberately unfolded into uniform linear chains. The success of your native PAGE research hinges on a single, critical factor: preventing unintended denaturation throughout your experimental workflow. Unwanted denaturation sabotages your results, leading to loss of enzymatic activity, disrupted protein-protein interactions, and erroneous conclusions about a protein's true state within the cell. This guide identifies the common adversaries of protein integrity in the lab and provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to ensure your research remains uncompromised.

Common Culprits of Denaturation in Native PAGE

The enemies of protein integrity can be introduced at nearly every stage of sample preparation and analysis. The table below summarizes the most frequent offenders and their consequences.

Table 1: Common Sources of Denaturation and Their Effects in Native PAGE

| Source of Denaturation | Mechanism of Action | Observed Effect in Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents (SDS) | Binds to polypeptide chains, masking intrinsic charge and unfolding the protein [4] [5] [6] | Altered migration, loss of activity, smeared or anomalous bands [7] |

| Reducing Agents (β-mercaptoethanol, DTT) | Cleaves disulfide bonds essential for tertiary and quaternary structure [6] | Dissociation of multi-subunit complexes, loss of native conformation [6] |

| Heat Treatment | Disrupts weak forces (e.g., hydrogen bonds) stabilizing the 3D structure [6] | Protein aggregation, incomplete entry into gel, or smeared bands [7] |

| Extreme pH Conditions | Alters the ionization state of amino acids, disrupting electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding [5] [7] | Protein precipitation, unfolding, or loss of native charge, leading to poor separation [5] |

| Proteolytic Enzymes | Cleaves peptide bonds, leading to protein fragmentation [7] | Multiple unexpected bands, disappearance of full-length protein, smearing [7] |

Troubleshooting FAQs: Identifying and Solving Common Problems

Why are my protein bands smeared?

Smeared bands are a common indicator of protein degradation or incomplete focusing.

- Primary Cause: Proteolytic degradation is a leading cause. Proteases present in the sample can cleave proteins during extraction or while the sample is on ice.

- Solution: Always include a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail in your lysis and storage buffers. Keep samples on ice at all times to slow enzymatic activity [7].

- Secondary Cause: The ionic strength of your sample may be too high due to high salt concentrations.

- Solution: Keep salt concentrations in your sample below 500 mM, and ensure your sample buffer is compatible with your running buffer system [7].

Why are my bands at unexpected molecular weights?

When proteins migrate to positions that do not align with their predicted size, it often points to issues with protein state or complex composition.

- Cause: In native PAGE, proteins separate based on their native charge, size, and shape, not purely on molecular weight. A large, tightly folded protein might migrate faster than a smaller, less compact one [5] [7]. Furthermore, multimeric complexes will be much larger than their individual subunits.

- Solution: This is not necessarily a problem but a feature of the technique. Compare your sample to native molecular weight markers, not denatured ones. Confirm the identity of the bands using an activity assay or a specific antibody.

Why is there little to no protein activity after elution from the gel?

Recovering active protein is a key advantage of native PAGE, but failure can occur if denaturants are present.

- Cause: Contamination of your gel system or buffers with SDS or reducing agents. Even trace amounts can be sufficient to denature proteins. This can occur from improperly rinsed equipment [6].

- Solution: Dedicate a set of gel-casting and running apparatus exclusively for native PAGE. Clean all equipment thoroughly before use to remove any residual SDS [6]. Also, avoid pH extremes during the elution process, as these can cause irreversible denaturation [5].

Why are my bands "smiling" or bulging?

Artifacts in band shape are often related to the conditions during the electrophoresis run itself.

- Cause ("Smiling" Bands): The buffer was made incorrectly, or the voltage is too high, causing the gel to overheat. This changes the buffer pH and impedes the migration of proteins at the warmer edges of the gel [7].

- Solution: Check the composition and pH of your running buffer. Run the gel at a lower voltage to reduce heating [7].

- Cause (Bulging Bands): The protein concentration loaded into the well is too high [7].

- Solution: Before electrophoresis, determine the total protein concentration using an assay like Bradford or BCA, and load an optimal, pre-determined amount of protein per well [7].

Proactive Protocols for Preserving Integrity

Sample Preparation Workflow for Native PAGE

Adhering to a disciplined, cold-based protocol is essential for maintaining proteins in their native state.

Critical Buffer Compositions

Using the correct buffers is non-negotiable. The table below outlines the key components for native PAGE systems.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function in Native PAGE | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Non-denaturing Detergents(e.g., n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside) | Solubilizes membrane proteins without disrupting protein-protein interactions [8]. | Must avoid ionic detergents like SDS. Use mild, non-ionic, or zwitterionic detergents. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents proteolytic degradation by inhibiting a broad spectrum of proteases [7]. | Essential for all steps before electrophoresis. Must be added fresh to buffers. |

| Native Loading Dye | Provides color to visualize loading and glycerol to weigh down the sample [6]. | Must not contain SDS or reducing agents. Often contains Coomassie G-250 [9]. |

| Tris-Based Running Buffers(e.g., Tris-Glycine, Tris-Borate) | Conducts current and maintains a stable pH above the protein's pI to ensure a net negative charge [5] [6]. | pH is critical; it must be above the protein's isoelectric point to drive migration toward the anode [7]. |

| Glycerol | Increases the density of the sample, allowing it to sink to the bottom of the well during loading [6] [10]. | A standard component of native sample buffer. |

| Coomassie Dye (in BN-PAGE) | Binds to proteins, imparting a negative charge proportional to mass for separation by size in Blue Native PAGE [8] [9]. | Used in the cathode buffer and sample buffer for first-dimension BN-PAGE. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

- NativePAGE Novex Bis-Tris Gels (Invitrogen): Pre-cast gels optimized for a wide range of native proteins and complexes, providing excellent resolution and reproducibility.

- Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (EDTA-Free) (Thermo Scientific): A versatile, concentrated cocktail that inhibits a wide range of serine, cysteine, aspartic, and metalloproteases. The EDTA-free formula is ideal for metal-dependent proteins.

- NativeMark Unstained Protein Standard (Invitrogen): A set of seven native proteins for estimating the molecular weight of soluble non-denatured proteins and complexes in the range of 20 to 1236 kDa.

- n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM): A high-purity, non-ionic detergent effective for solubilizing membrane protein complexes while maintaining their stability and native interactions.

- Coomassie G-250: The key dye used in Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) to impart charge to proteins without denaturation, enabling separation based on size and shape [8] [9].

By understanding these enemies of protein integrity and implementing the recommended defensive strategies, you can significantly enhance the reliability and biological relevance of your Native PAGE research.

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental technique for separating proteins based on their intrinsic physical properties while maintaining their native conformation. Unlike denaturing methods such as SDS-PAGE, which dismantles protein structure and imparts a uniform charge, Native PAGE preserves the protein's higher-order structure, enzymatic activity, and interaction capabilities [1]. This technical support center focuses on the core principles of how a protein's net charge, size, and shape collectively govern its migration in native gels, all within the critical context of preventing artifactual denaturation. Mastering these principles is essential for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on accurate analysis of protein complexes, oligomeric states, and functional isoforms.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Native PAGE Issues

Diagnosing and resolving issues in Native PAGE requires a systematic understanding of how native protein properties interact with electrophoretic conditions. The following guide addresses common problems, their root causes, and proven solutions to ensure data integrity.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Band Distortion and Migration Issues

| Problem Observed | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smiling or Frowning Bands (curved bands) | Uneven heat distribution across the gel (Joule heating) [11] [12]. | Run the gel at a lower voltage; use a constant current power supply; perform electrophoresis in a cold room or with ice packs [11] [12]. |

| Smeared Bands | Sample degradation by proteases; excessive voltage causing local heating; protein aggregation [11] [7]. | Keep samples on ice; use fresh, sterile buffers; include protease inhibitors; run the gel at a lower voltage; ensure buffer composition is correct [11] [7]. |

| Poor Band Resolution | Suboptimal gel concentration for the target protein size; overloading of wells; insufficient run time [11]. | Optimize the acrylamide percentage for your protein size range; load a smaller amount of sample; adjust the run time for sufficient separation [11]. |

| Edge Effect (distorted bands in peripheral lanes) | Empty wells at the periphery of the gel, leading to an uneven electric field [12]. | Load a control protein or sample buffer into any unused wells to ensure a uniform electric field across the gel [12]. |

| Unexpected Migration (e.g., larger protein migrates faster) | Protein's native charge influences mobility more than its size [13]. | Remember separation is based on charge, size, and shape. A highly charged large protein may migrate faster than a small, low-charge protein. Analyze results considering all three factors. |

| Fmoc-Gly-OH-1-13C | Fmoc-Gly-OH-1-13C|13C-Labeled Glycine Derivative | Fmoc-Gly-OH-1-13C is a 13C-labeled Fmoc-protected glycine for peptide synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH-15N | Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH-15N, MF:C24H27NO6, MW:426.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Faint, Absent, or Aberrant Bands

| Problem Observed | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Faint or No Bands | Protein concentration too low; incomplete transfer (if blotting); sample degradation [11] [7]. | Confirm protein concentration pre-loading; use a positive control/ladder; check sample handling and storage conditions [11] [7]. |

| Protein Samples Migrated Out of Well Before Run | Significant delay between sample loading and applying electric current, allowing diffusion [12]. | Minimize the time between loading the first sample and starting the electrophoresis run [12]. |

| Yellow Sample Color | Running buffer is at an incorrect, often acidic, pH [7]. | Prepare a fresh running buffer, ensuring the correct pH according to the protocol [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE?

A1: The key difference lies in the preservation of protein structure. SDS-PAGE uses the denaturing detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and heat to unfold proteins, giving them a uniform negative charge and allowing separation based almost exclusively on molecular weight [7] [1]. Native PAGE uses non-denaturing conditions, allowing proteins to retain their native 3D structure, charge, and enzymatic activity. Separation depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and shape [1] [13].

Q2: Why does my protein not enter the resolving gel or migrate in the wrong direction?

A2: In Native PAGE, a protein's migration is determined by its net charge at the running buffer's pH. A protein will not enter the gel if it has a net charge of zero (it is at its isoelectric point, or pI). If it migrates towards the cathode (the negative electrode), it means the protein has a net positive charge at the operating pH, which occurs when the buffer pH is below the protein's pI [13]. Check the pI of your protein and the pH of the running buffer.

Q3: How can I prevent protein denaturation during Native PAGE?

A3: To prevent denaturation:

- Avoid Denaturants: Do not use SDS, urea, or reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol in your buffers unless specifically required for a modified protocol [1].

- Control Temperature: Run the gel at lower voltages or in a cold room to minimize heat generation, which can cause denaturation and aggregation [11] [12].

- Use Compatible Buffers: Ensure your sample and running buffers are at an appropriate pH and ionic strength to maintain protein stability and solubility.

- Consider Charge-Shift Reagents: For basic proteins or membrane proteins prone to aggregation, using a system like NativePAGE Bis-Tris with Coomassie G-250 can help maintain solubility and confer negative charge without denaturation [14].

Q4: My protein is active after Native PAGE, but the band pattern is complex. Why?

A4: This is a common and advantageous outcome of native electrophoresis. The complex banding pattern likely reflects the native state of your protein sample, showing different oligomeric states (e.g., dimers, tetramers), functional isoforms with different post-translational modifications, or complexes with other proteins or ligands [14] [1]. Each of these states has a unique combination of size, charge, and shape, leading to distinct migration positions.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Determining Protein Charge via Native Gel Electrophoresis

This protocol is adapted from studies on cytochrome c, which demonstrated that measured charge in solution can differ significantly from theoretical calculations due to ion binding [15].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Dialyze the purified protein into a desired low-concentration buffer (e.g., 10 mM BIS-TRIS propane, pH 7.0) to standardize ionic conditions.

- Adjust the ionic strength of the sample and running buffer to a defined level (e.g., 100 mM) using salts like KCl. Avoid sulfates if studying cation-binding proteins, as they can neutralize charge [15].

- Do not heat or add denaturants to the sample.

2. Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use a pre-cast native gel system (e.g., Tris-Glycine, Bis-Tris) appropriate for your protein's size and pI [14].

- Load the dialyzed protein sample alongside a native marker.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 150V) at 4°C to minimize heat-induced artifacts. Stop the run when the dye front approaches the bottom.

3. Analysis:

- After staining, measure the migration distance of your protein and the markers.

- The relative mobility can be used to assess the protein's effective charge under the experimental conditions. A protein with a higher negative charge density will migrate faster towards the anode than a similar-sized protein with a lower charge [14] [13].

Protocol: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) for Metalloprotein Analysis

This modified protocol allows for high-resolution separation while retaining bound metal ions and, for many enzymes, biological activity [9].

1. Modified Buffer Preparation:

- Sample Buffer: Omit SDS and EDTA from the standard Laemmli buffer. A suggested formulation is 100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris Base, 10% glycerol, 0.01875% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% Phenol Red, pH 8.5 [9].

- Running Buffer: Reduce SDS concentration to 0.0375% and omit EDTA. A suggested formulation is 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7 [9].

- Crucially, do not heat the samples.

2. Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use standard pre-cast polyacrylamide gels (e.g., 12% Bis-Tris).

- Pre-run the gel in ddHâ‚‚O for 20-30 minutes to remove storage buffers and unpolymerized acrylamide.

- Load samples mixed with the NSDS sample buffer.

- Run the gel at constant voltage (e.g., 200V) at room temperature.

3. Post-Electrophoresis Analysis:

- Proteins can be visualized with standard stains like Coomassie.

- Retained metal ions can be detected using techniques like LA-ICP-MS (Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry) or specific in-gel fluorescent stains (e.g., TSQ for Zn²âº) [9].

- Enzymatic activity can be assayed via in-gel zymography techniques.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials

Selecting the correct reagents is critical for successful Native PAGE and preventing undesired denaturation. The table below summarizes key solutions and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE

| Reagent / Material | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine Native Gels | Traditional system for separating smaller proteins (20-500 kDa) in a high pH range (8.3-9.5), ideal for proteins stable at alkaline pH [14]. |

| Tris-Acetate Native Gels | Provides better resolution for larger molecular weight proteins (>150 kDa) in a slightly lower pH range (7.2-8.5) [14]. |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels | A versatile system using Coomassie G-250 dye in the cathode buffer to confer a net negative charge on all proteins, including those with basic pIs. Crucial for studying membrane proteins and preventing aggregation [14]. |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | A charge-shift molecule that binds non-specifically to hydrophobic protein patches, imparting a negative charge without denaturation. This allows all proteins to migrate toward the anode regardless of their native pI [14]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to sample preparation buffers to prevent proteolytic degradation during isolation and electrophoresis, which can cause smearing or loss of signal [7]. |

| Glycerol | A common component of sample buffers to increase density, allowing samples to sink neatly into the wells without diffusing [9]. |

Visualization: Workflow and Decision Pathway

Native PAGE Separation Workflow

Native PAGE Gel Selection Guide

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, and why does it matter for function? Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) separates proteins under non-denaturing conditions, preserving their higher-order structure (quaternary and tertiary), post-translational modifications, and biological activity. In contrast, SDS-PAGE denatures proteins into their primary structure, coating them with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to impart a uniform negative charge, separating them primarily by molecular weight. For functional studies, native PAGE is critical because a protein's biological function depends entirely on its intact three-dimensional conformation [7].

Q2: My protein is not migrating as expected in native PAGE. What could be wrong? Protein mobility in native PAGE depends on both the protein's intrinsic charge and its hydrodynamic size, which is dictated by its folded shape. Unlike SDS-PAGE, where migration is proportional to molecular weight, a small but loosely folded protein could migrate slower than a larger, tightly folded one in native PAGE [7]. Ensure your buffer pH is appropriate to maintain the protein's native charge, and consider that multimeric complexes will be preserved, affecting their migration [7].

Q3: How can I verify that my protein's native structure and function are intact after separation? A powerful emerging technique is in-gel refolding and fluorescence detection. For fluorescent proteins like GFP, fully denatured samples can be refolded within the gel by cyclodextrin-mediated removal of SDS in the presence of 20% methanol, enabling direct fluorescence detection of the properly folded protein [16]. This confirms the protein has regained its functional conformation.

Q4: What are the key considerations for buffer selection in native PAGE?

- pH: The running buffer pH must be above the isoelectric points (pI) of the proteins being separated to maintain a net negative charge, ensuring migration towards the anode [7].

- Composition: A Tris-glycine buffer is typically used. For specialized applications, Tricine buffers are ideal for separating very low molecular weight proteins or peptides [7].

- Additives: To maintain reducing conditions and prevent disulfide bond formation, adding a reducing agent to the buffer is recommended [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Native PAGE Issues and Solutions

The following table outlines common problems, their potential causes, and solutions to help you maintain native protein structure during your experiments.

| Problem Observed | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smiling or bulging bands | Buffer composition error or incorrect running voltage causing overheating [7]. | Check running buffer composition and run at a lower voltage to prevent heating [7]. |

| Smeared bands | Sample insufficiently prepared; may contain aggregates or be partially denatured [7]. | Ensure sample is not overly concentrated. Keep salt concentrations below 500 mM where possible [7]. |

| Multiple or unexpected bands | Protein degradation, oxidation, or dephosphorylation [7]. | Use protease and phosphatase inhibitors in buffers. Include sodium azide to prevent microbial growth [7]. |

| Poor or no separation | Gel density is inappropriate for the target protein size [7]. | Use a gradient gel to resolve a wider range of protein sizes or adjust the acrylamide percentage (e.g., 10% for >70kDa proteins) [7]. |

| Loss of protein function | Protein denaturation during sample preparation or electrophoresis. | Avoid heating and denaturing detergents like SDS. Use mild, non-denaturing detergents if necessary for solubility. |

Research Reagent Solutions for Native Structure Analysis

This table details essential reagents and materials for successful native PAGE experiments aimed at preserving biological function.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Native PAGE |

|---|---|

| Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix | A strong, hydrophilic, and inert matrix that separates proteins based on charge, size, and shape without denaturing them [7]. |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | A common discontinuous buffering system that stacks and then resolves proteins, maintaining a pH that keeps proteins charged and native [7]. |

| Cyclodextrin | Used in post-electrophoresis refolding protocols to remove SDS from gels, enabling denatured proteins like GFP to regain their native, fluorescent structure [16]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Proteins of known molecular weight and native state used to calibrate size separation; prestained markers can monitor migration in real-time [7]. |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitors | Added to buffers to prevent protein degradation or modification (e.g., truncation, dephosphorylation) that can alter native structure and create artifactual bands [7]. |

Experimental Workflow for Maintaining Native Structure

The diagram below outlines a general workflow for a native PAGE experiment, highlighting key decision points for preventing denaturation.

Advanced Techniques: Linking Structure to Function

Modern structural biology leverages advanced visualization and analysis tools to directly link a protein's native structure to its function. The following diagram illustrates an integrative workflow.

Native Top-Down Mass Spectrometry (nTDMS) is a breakthrough for characterizing intact proteoforms and their complexes. It preserves the critical link between protein modifications and their biological interactions [17]. The precisION software package enables the detection of "hidden" post-translational modifications (PTMs) like phosphorylation and glycosylation that are essential for function but can be missed by standard methods [17]. This allows researchers to connect specific proteoforms directly to their functional states in a way that denaturing methods cannot.

Essential Controls for Valid Experimental Results

- Negative Tissue Controls: Use a cell or tissue sample known not to express your target protein. A signal in this control indicates non-specific detection by your primary antibody [7].

- No-Primary Antibody Control: Omit the primary antibody during detection. A positive signal shows direct binding of the secondary antibody to proteins in your sample [7].

- Loading Controls: Use housekeeping proteins (e.g., β-actin) expressed in your sample to confirm consistent loading across wells and normalize quantification [7].

Practical Protocols for Pristine Proteins: BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and Activity Staining

In the study of proteins, function is dictated by structure, and often, by the intricate quaternary structures of protein complexes. For researchers investigating vital systems like the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) machinery or photosynthetic supercomplexes, preserving these native structures during analysis is paramount. Blue-Native and Clear-Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE) are two powerful techniques that fulfill this need, allowing for the separation of intact protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions. BN-PAGE, originally developed by Schägger and Von Jagow in the 1990s, has become an indispensable tool for gaining insights into the structure and function of multi-protein complexes [18] [19]. The core challenge in native electrophoresis is to solubilize and separate complexes while minimizing denaturation, thereby maintaining enzymatic activity and native protein-protein interactions. This guide provides a strategic comparison of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE, empowering you to select the optimal technique for your experimental goals, whether they involve assembly pathway analysis, supercomplex composition, or pathological mechanism investigation in genetic disorders [18].

Core Principles and Historical Development

Both BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE are designed to separate native protein complexes based on their size and shape, but they employ different strategies to achieve this.

BN-PAGE relies on the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250. This dye binds non-covalently to the hydrophobic surfaces of proteins, imparting a uniform negative charge shift. This charge shift forces even basic proteins to migrate towards the anode at neutral pH and, crucially, prevents the aggregation of hydrophobic proteins by keeping them soluble in the absence of detergent during electrophoresis [18] [19]. The characteristic blue color of the complexes during separation gives the technique its name.

CN-PAGE, a more recent variant, replaces the Coomassie dye with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer. These mixed micelles similarly induce a charge shift on membrane proteins, enhancing their solubility and migration. A key distinction is the absence of the blue dye, hence "clear-native," which eliminates potential interference with downstream applications like in-gel enzyme activity staining [20] [19].

BN-PAGE vs. CN-PAGE: A Direct Technical Comparison

The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE is not a matter of one being superior to the other, but rather which is better suited for a specific application. The following table summarizes their core characteristics to guide your decision.

Table 1: Strategic comparison between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Feature | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Agent | Coomassie Blue G-250 dye [19] | Mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents [19] |

| Key Advantage | Robust separation of individual OXPHOS complexes; widely used and validated [18] | No dye interference, superior for in-gel activity assays [20] [19] |

| Ideal For | Western blot analysis, studying assembly pathways, resolving individual complexes [18] | In-gel enzyme activity staining (Complexes I, II, IV, V), analyzing labile supercomplexes [18] [19] |

| Limitations | Dye can interfere with activity staining and mass spectrometry [19] | Can be less robust for some complexes; may not resolve all complexes as well as BN-PAGE [18] |

| Visual Output | Blue bands during electrophoresis [8] | Clear/colorless bands during electrophoresis [19] |

Decision Framework: Selecting the Right Technique

To make an informed choice, align the fundamental strengths of each technique with your primary experimental objective. The following workflow diagram provides a visual guide for this decision-making process.

Guidance for Specific Research Scenarios

- Studying Mitochondrial Respiratory Complexes: For initial characterization and assembly studies of OXPHOS complexes from mitochondria, BN-PAGE is the robust and standard choice [18]. If your focus shifts to quantifying the enzymatic activity of specific complexes like Complex V (ATP synthase), switching to CN-PAGE is highly recommended, especially as recent protocols include enhancement steps that markedly improve the sensitivity of in-gel Complex V activity staining [18] [19].

- Analyzing Photosynthetic Supercomplexes: Research on thylakoid membrane complexes, such as Photosystem I and II supercomplexes in plants, benefits from the mild conditions of CN-PAGE or optimized BN-PAGE protocols. Using detergent mixtures like n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside with digitonin for solubilization in BN-PAGE can help preserve fragile mega- and supercomplexes for analysis [21].

- Troubleshooting Poor Resolution: If you encounter smearing or poor band resolution in BN-PAGE, consider the following. First, optimize the detergent-to-protein ratio during solubilization [8]. Second, ensure the use of a linear gradient gel (e.g., 4-16%) instead of a single-concentration gel to better resolve complexes of vastly different sizes [8] [21]. For CN-PAGE, the composition and concentration of the detergent charge mix are critical parameters to optimize.

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Core Sample Preparation Workflow

A critical first step in both techniques is the proper isolation and solubilization of protein complexes to preserve their native state. The workflow below outlines the key steps, highlighting points of divergence between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Sample Isolation: It is highly recommended to isolate mitochondria or chloroplasts from cells or tissues before analysis. While whole-cell extracts can be used, they may result in a weaker signal and lower resolution due to the high abundance of cytosolic proteins [8].

- Membrane Solubilization: Resuspend the isolated membrane fraction in a buffer containing 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid and 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0, supplemented with protease inhibitors [8]. Add a mild, non-ionic detergent.

- For individual complexes, use n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (e.g., 1-2% w/v) [18] [8].

- For supercomplexes, use the milder detergent digitonin (e.g., 1-4% w/v) [19] [21]. A mixture of 1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside and 1% digitonin has also been successfully used for resolving large photosystem I megacomplexes [21].

- Incubation and Clarification: Mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes to allow for complete solubilization. Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 72,000 x g for 30 minutes, though 16,000 x g in a microcentrifuge can suffice for small volumes) to pellet insoluble material [8].

- Sample Preparation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Successful native PAGE requires specific reagents to maintain protein complexes in their functional, folded state.

Table 2: Essential reagents for BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Reagent | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside | Mild, non-ionic detergent for solubilizing individual protein complexes [18] [8]. | Optimal for resolving Complexes I-V; harsher than digitonin. |

| Digitonin | Very mild, non-ionic detergent for preserving supercomplexes [19]. | Use for studying respirasomes or photosynthetic supercomplexes. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye providing charge for electrophoresis in BN-PAGE [18] [19]. | Can interfere with in-gel activity assays and MS; handle accordingly. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; supports solubilization and prevents aggregation [18] [19]. | Zero net charge at pH 7.0; does not interfere with electrophoresis. |

| Bis-Tris Buffer | Primary buffer component for native gels and running buffers [8] [19]. | Provides stable pH (~7.0) crucial for native conditions. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents protein degradation during sample preparation [8]. | Essential for preserving labile subunits and assembly factors. |

| Pde IV-IN-1 | Pde IV-IN-1, MF:C20H23ClN4O2, MW:386.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pemetrexed-d5 | Pemetrexed-d5|Isotope-Labeled Antineoplastic Standard | Pemetrexed-d5 is a deuterated isotope-labeled internal standard for LC-MS/MS research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Advanced Applications and Downstream Analyses

The true power of native PAGE is unlocked by coupling it with various downstream techniques.

- In-Gel Enzyme Activity Staining: This is a major application where CN-PAGE excels. After CN-PAGE, the resolved complexes in the gel remain active and can be assayed for function. Established histochemical methods can detect the activities of Complexes I, II, IV, and V directly in the gel [18] [19]. A limitation is the comparative insensitivity for Complex IV and the lack of a reliable assay for Complex III activity [18].

- Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis (2D-PAGE): Both BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE can be followed by a second dimension of denaturing SDS-PAGE. In this 2D setup, the first dimension separates the native complexes by size, and the second dimension denatures and separates the individual subunits of each complex by molecular weight. This powerful combination, known as BN/SDS-PAGE or CN/SDS-PAGE, is invaluable for determining the subunit composition of complexes and identifying assembly intermediates [18] [8].

- Western Blotting and Mass Spectrometry: Bands from one-dimensional native gels can be transferred to membranes for immunodetection with specific antibodies, or excised and analyzed by mass spectrometry to identify component proteins [19] [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can I use commercial pre-cast gels for BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE? Yes, for greater convenience, pre-cast native linear gradient polyacrylamide gels (e.g., 3–12% or 4–16%) and buffers for BN-PAGE are commercially available. For CN-PAGE, these commercial native gels can be combined with the cathode and anode buffers recommended in specific CN-PAGE protocols [19].

Q2: Why is there no in-gel activity stain for Complex III? The lack of a reliable in-gel activity stain for Complex III (cytochrome bc1 complex) is a recognized limitation of the technique [18]. The specific reagents and electron transfer pathways required for its activity are difficult to implement in the gel matrix post-electrophoresis.

Q3: My protein complexes are not resolving clearly and appear smeared. What could be the cause? Smearing is often a sign of protein degradation or suboptimal solubilization. Ensure your samples are kept on ice, use fresh protease inhibitors, and check the viability of your isolated organelles. Additionally, titrate the detergent-to-protein ratio, as too little detergent causes incomplete solubilization and aggregation, while too much can dissociate complexes [8].

Q4: How does the choice of detergent impact the analysis of supercomplexes? The choice of detergent is critical. Dodecyl maltoside is effective for solubilizing individual OXPHOS complexes but can disrupt the weaker interactions in supercomplexes. Digitonin, being milder, is the detergent of choice for studying supercomplexes (e.g., respirasomes containing Complexes I, III, and IV) as it preserves these higher-order structures [19] [21].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is maintaining the native state of membrane protein complexes crucial for my research, and what are the primary challenges?

Maintaining the native state is essential for studying the true structure, function, and interactions of membrane protein complexes, which are often disrupted by traditional denaturing methods. The primary challenges include their inherent hydrophobicity, which makes them prone to aggregation and loss of activity when removed from their lipid environment, and their sensitivity to harsh detergents and physical conditions that can dismantle complex subunits and post-translational modifications [22]. Success in native analysis hinges on preserving these delicate non-covalent interactions throughout the entire sample preparation workflow.

FAQ 2: How do I choose the correct native PAGE system for my specific membrane protein complex?

The choice of native PAGE system depends on the protein's isoelectric point (pI), size, and hydrophobicity. There is no universal system, and selection is critical for maintaining protein stability and achieving high-resolution separation. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of common native gel chemistries:

Table: Guide to Native PAGE Gel System Selection

| Gel System | Operating pH Range | Key Features | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-Glycine | 8.3 - 9.5 | Traditional Laemmle system; proteins separate based on native charge and size. | Keeping the native net charge; studying smaller proteins (20-500 kDa) [14]. |

| Tris-Acetate | 7.2 - 8.5 | Provides better resolution for larger proteins. | Keeping the native net charge; studying larger molecular weight proteins (>150 kDa) [14]. |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris | ~7.5 | Uses Coomassie G-250 dye to confer a uniform negative charge. | Membrane/hydrophobic proteins; separating by molecular weight regardless of pI; analyzing oligomeric states [14]. |

FAQ 3: What are the most critical steps in sample preparation to prevent denaturation of my membrane protein complex?

The most critical steps involve using the correct lysis buffer, avoiding denaturing agents, and carefully controlling temperature.

- Lysis Buffer Selection: Use mild, non-ionic detergents like NP-40 or Triton X-100 to solubilize membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions. For highly hydrophobic membrane proteins, zwitterionic detergents like CHAPS are more effective [23]. Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer can be used but may disrupt some protein complexes due to its SDS content [23].

- Inhibitors: Always include a fresh protease inhibitor cocktail to prevent protein degradation and phosphatase inhibitors if studying phosphorylated proteins [23] [24].

- Temperature: Perform all lysis and preparation steps on ice or at 4°C to minimize enzymatic activity and denaturation [23].

- Sonication: For nuclear and membrane-bound proteins, sonication is a crucial step to break up cellular components and enrich the target protein. Keep samples on ice during the process to avoid heat denaturation [24].

FAQ 4: I am observing poor transfer efficiency or high background in my western blot after native PAGE. What could be the cause?

Poor transfer and high background are common issues that can often be traced to the membrane, buffer conditions, or detection steps.

- Membrane Choice for NativePAGE: When using NativePAGE Bis-Tris gels, you must use a PVDF membrane. Nitrocellulose is incompatible as it tightly binds the necessary Coomassie G-250 dye [14].

- Transfer Buffer Optimization: The composition of your transfer buffer significantly impacts efficiency. For large proteins (>100 kDa), adding a small amount of SDS (0.01-0.02%) to the transfer buffer can facilitate elution from the gel. However, too much SDS can prevent binding to the membrane. Methanol concentration (typically 10-20%) helps bind proteins to the membrane but can reduce pore size and transfer efficiency; it must be balanced carefully [25].

- High Background: This can result from insufficient blocking, antibody concentrations that are too high, or inadequate washing. Optimize your blocking buffer (avoid milk if cross-reactivity is an issue) and ensure antibodies are diluted in buffer containing detergent (e.g., 0.1-0.2% Tween 20). Always handle membranes with clean forceps to avoid contamination [26].

Optimized Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Preparation of Membrane Protein Complexes for Native PAGE and Western Blotting

This protocol is designed for the extraction of membrane-bound proteins from cultured cells under native conditions.

Solutions and Reagents:

- Extraction Buffer: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgClâ‚‚.

- Protease Inhibitor Cocktail: Add fresh to all buffers.

- Phosphatase Inhibitors: Add if studying protein phosphorylation.

- RIPA Buffer: For final solubilization of the membrane fraction.

- Native Sample Buffer: Compatible with your chosen native PAGE system (e.g., Tris-Glycine Native Sample Buffer or NativePAGE Sample Buffer) [14].

Procedure:

Cell Lysis and Homogenization:

- Harvest cells and wash twice with cold PBS by centrifugation (100–500 x g, 5 min, 4°C).

- Resuspend the cell pellet in adequate cold Extraction Buffer containing inhibitors.

- Gently homogenize the suspension 20-30 times with a Dounce homogenizer. Avoid generating bubbles to prevent sample loss and potential denaturation [24].

Isolation of Membrane Fraction:

- Centrifuge the homogenized suspension at 2,000 x g for 5 min at 4°C. This pellets nuclei and cell debris.

- Carefully transfer the supernatant (S1) to a new tube. Centrifuge S1 again at a high speed of 17,000 x g for 20 min at 4°C.

- The resulting pellet contains the membrane fraction [24].

Solubilization of Membrane Proteins:

- Add RIPA buffer (or another suitable mild detergent buffer) to the membrane pellet to solubilize the proteins. Gently pipette or vortex to mix.

- Incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes to allow for complete solubilization [24].

Sonication (Critical Step):

- To fully disrupt membranes and release proteins, sonicate the lysate on ice. Use short pulses to avoid heating (e.g., 3 seconds on, 10 seconds off, for 5-15 cycles at 40 kW). Optimization of time and intensity for your specific instrument is required [24].

Clarification and Concentration Measurement:

Sample Preparation for Native PAGE:

- Dilute the lysate with the appropriate 2X Native Sample Buffer. Do not boil the samples.

- For multi-pass transmembrane proteins, heating can cause aggregation. Instead, incubate samples at room temperature for 15-20 minutes or on ice for 30 minutes to prepare for loading [24].

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and critical decision points for preparing membrane protein complexes, highlighting steps essential for preventing denaturation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Native Membrane Protein Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Detergents (NP-40, Triton X-100, CHAPS) | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving native protein-protein interactions and complex integrity. | NP-40/Triton for whole cell extracts; CHAPS for hydrophobic membrane proteins; avoid SDS for native complexes [23]. |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents co-purified proteases and phosphatases from degrading the target protein or altering its modification state. | Must be added fresh to all lysis and extraction buffers to maintain efficacy [23] [24]. |

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gels & Coomassie G-250 | Native gel system that uses dye to confer uniform negative charge, allowing separation by size and shape regardless of pI. | Essential for membrane proteins and analyzing oligomeric states; requires PVDF membrane for blotting [14]. |

| PVDF Membrane | Microporous membrane used to immobilize proteins after electrophoresis for western blotting. | Required for use with NativePAGE systems; pre-wet in 100% methanol before use [14] [26]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) & PBST | Isotonic buffer for washing cells and sample preparation. PBST (with Tween-20) is used for washing blots to reduce background. | Maintains isotonicity and pH; PBST is crucial for effective immunoassay washing [27]. |

| RIPA Buffer | Effective lysis buffer for total cellular extracts, including membrane and nuclear fractions. | Contains ionic detergents and may disrupt some weak protein complexes; use with caution for native work [23] [24]. |

| 3-Cyclopropoxy-5-methylbenzoic acid | 3-Cyclopropoxy-5-methylbenzoic Acid|Research Chemical | High-purity 3-Cyclopropoxy-5-methylbenzoic acid for research use. A versatile benzoic acid derivative for medicinal chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle-p-nitro-Phe-Gln-Arg-NH2 | Abz-Thr-Ile-Nle-p-nitro-Phe-Gln-Arg-NH2, MF:C43H65N13O11, MW:940.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Solubilization Issues in BN-PAGE

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| No or poor separation of complexes on BN-PAGE gel | Incorrect detergent choice for target complex; Insufficient detergent concentration; Overly harsh solubilization damaging complexes; Low abundance of target complex masked by abundant proteins. | Perform a detergent screening assay (see Experimental Protocol 1); Increase detergent-to-protein ratio empirically [28]; Include low ionic strength salts (e.g., aminocaproic acid) to support solubilization [28]; Pre-fractionate sample or use affinity chromatography to enrich low-abundance complexes [28]. |

| Unexpected band patterns or absence of expected bands | Detergent choice influencing complex stability (e.g., disruption of supercomplexes); Coomassie dye disrupting some protein-protein interactions [29]; Partial denaturation of complexes. | Use digitonin to preserve supercomplexes instead of dodecylmaltoside [28]; Consider Colorless Native-PAGE (CN-PAGE) if dye is suspected of disrupting interactions [29]; Verify complex integrity and activity via enzymatic assays or other native techniques post-solubilization. |

| Protein smearing on the gel | Presence of interfering salts or solutes; Incomplete solubilization; Protein aggregation. | Desalt sample or change buffer using dialysis or ultrafiltration [28]; Optimize solubilization time and temperature; Ensure mild, non-ionic detergents are used and that harsh ionic detergents like SDS are avoided [28] [29]. |

| Weak or no signal for immunodetection | Antibody raised against denatured epitopes may not recognize native protein [29]; Target abundance too low. | Use antibodies validated for native protein detection [29]; Combine BN-PAGE with a second dimension SDS-PAGE (2D-BN/SDS-PAGE) for immunodetection of subunits [30]; Increase sample loading and employ more sensitive detection methods (e.g., silver stain). |

Troubleshooting Detergent-Related Issues in Structural Biology

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Protein denaturation during Cryo-EM grid preparation | Denaturation at the air-water interface [31]; Destabilization of protein by detergent micelles. | Use supports like hydrophilized graphene to prevent contact with the air-water interface [31]; Screen alternative detergents (e.g., GDN, LMNG) or non-detergent amphiphiles (amphipols, nanodiscs) [32]. |

| Protein compaction or deformation in Cryo-EM | Vacuum-induced dehydration during cryo-landing for native MS-Cryo-EM hybrid methods [33]. | Employ laser-induced rehydration techniques to restore native structure post-landing [33]. |

| Heterogeneity and poor resolution in Cryo-EM | Detergent micelle size and heterogeneity interfering with image processing [32]; Protein instability in detergent. | Use detergents with small, uniform micelles like LMNG [32]; Transfer protein into a more native environment like nanodiscs or SMALPs for grid preparation [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between using dodecylmaltoside and digitonin for solubilization?

The key difference lies in their mildness and the type of information they can reveal. Dodecylmaltoside is effective for solubilizing individual, stable protein complexes [28]. In contrast, digitonin is even milder and is the detergent of choice for preserving larger, more delicate assemblies known as supercomplexes, where several individual complexes associate stably [28]. Using dodecylmaltoside might lead you to conclude that only individual complexes exist, while digitonin can uncover a more native, higher-order organization.

Q2: How do I determine the optimal detergent concentration for my membrane protein sample?

The optimal concentration is both protein and complex-specific. A standard approach is to perform a detergent titration, testing a range of detergent-to-protein ratios (w/w or v/w) while keeping other conditions constant [28]. The functionality and integrity of the solubilized complex should then be assessed, for example, through an enzymatic activity assay or by analyzing the band pattern on a BN-PAGE gel. The goal is to find the lowest concentration that achieves complete solubilization without dissociating the complex of interest.

Q3: My protein is prone to denaturation. What alternatives exist beyond traditional detergents?

Several innovative alternatives can maintain protein stability:

- Nanodiscs: Use a membrane scaffold protein (MSP) to encase your membrane protein within a small patch of lipid bilayer, providing a near-native environment [32].

- Amphipols: These are amphiphilic polymers that adsorb onto the hydrophobic surfaces of membrane proteins, keeping them soluble without forming large micelles [32].

- SMALPs (Styrene Maleic Acid Lipid Particles): These polymers directly solubilize membranes, forming nanodiscs that contain your protein surrounded by its native lipids, hence "native nanodiscs" [32].

Q4: Why might my antibody fail to detect a protein on a BN-PAGE gel, and how can I address this?

This is a common issue. BN-PAGE separates proteins in their native state. If your antibody was generated using a denatured antigen (common with SDS-PAGE), it may recognize linear epitopes that are buried or folded in the native complex. The solution is to use an antibody validated for native applications. If such an antibody is unavailable, a powerful workaround is to perform two-dimensional electrophoresis (2D-BN/SDS-PAGE), where the native complexes from the BN-PAGE gel are denatured and separated in a second dimension by SDS-PAGE. You can then perform immunodetection on this second gel, where the subunits are denatured [30] [29].

Experimental Protocols

Experimental Protocol 1: Detergent Screening for Optimal Complex Solubilization

Purpose: To identify the most suitable detergent and conditions for solubilizing a native membrane protein complex without disrupting its integrity.

Background: The choice of detergent is critical for the success of BN-PAGE and downstream structural studies. This protocol outlines a systematic approach for detergent optimization [28] [34].

Materials:

- Membrane sample (e.g., isolated mitochondria, chloroplasts, or cellular membranes)

- Selection of mild, non-ionic detergents (e.g., Dodecylmaltoside, Digitonin, Triton X-100)

- Solubilization buffer (e.g., containing 50 mM NaCl, 10% Glycerol, and 20-50 mM Bis-Tris or Imidazole buffer, pH 7.0)

- BN-PAGE gel equipment

Method:

- Prepare Detergent Stocks: Create stock solutions of each detergent to be tested. Ensure digitonin is fully dissolved by warming to 90-100°C and then keeping it on ice [35].

- Aliquot Membrane Sample: Dispense equal amounts of membrane protein (e.g., 50-100 µg) into separate microcentrifuge tubes.

- Solubilization: Add solubilization buffer to each aliquot. Then, add different detergents at various detergent-to-protein ratios (e.g., for digitonin, test 1-10 g/g protein; for dodecylmaltoside, test 0.5-2.0% (w/v)) [28]. Include a low ionic strength salt like 500 mM aminocaproic acid to support the process.

- Incubate: Mix gently and incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

- Clarify: Centrifuge the samples at high speed (e.g., 100,000 x g for 30 min at 4°C) to pellet unsolubilized material.

- Analyze: Collect the supernatant and analyze by BN-PAGE. Assess the solubilization efficiency and integrity of the complexes by the banding pattern, followed by activity assays or immunoblotting.

Experimental Protocol 2: Two-Dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE for Subunit Analysis

Purpose: To separate native protein complexes in the first dimension and their denatured constituent subunits in the second dimension.

Background: This powerful technique combines the complex-level separation of BN-PAGE with the high-resolution subunit separation of SDS-PAGE, ideal for immunodetection of low-abundance proteins [30].

Materials:

- Solubilized protein sample (from Protocol 1)

- Equipment for BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE

- Equilibration buffer (1% SDS, 1% β-mercaptoethanol)

Method:

- First Dimension (BN-PAGE): Perform BN-PAGE according to standard protocols [28] [29].

- Gel Strip Excison: After electrophoresis, carefully excise the lane of interest from the BN-PAGE gel.

- Equilibration: Incubate the gel strip in equilibration buffer for 30-60 minutes with gentle agitation. This denatures the proteins and coats them with SDS.

- Second Dimension (SDS-PAGE): Place the equilibrated gel strip horizontally on top of a standard SDS-polyacrylamide gel. Seal it with agarose.

- Electrophoresis: Run the SDS-PAGE gel.

- Analysis: Visualize the separated subunits using Coomassie or silver staining, or proceed to immunoblotting [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Detergents and Amphiphiles for Native Protein Studies

| Reagent | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Dodecylmaltoside (DDM) | Mild, non-ionic detergent for solubilizing individual membrane protein complexes [28] [32]. | Considered a standard "mild" detergent; effective for solubilizing many complexes but can disrupt weaker supercomplexes [28]. |

| Digitonin | Very mild, non-ionic detergent purified from natural sources; ideal for preserving supercomplexes [28] [35]. | Complex mixture; requires heating to 90-100°C for solubilization before use [35]; key for revealing supercomplex organization in respiratory chains [28]. |

| Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) | Synthetic detergent widely used in Cryo-EM for enhanced stability [32] [34]. | Has smaller, more uniform micelles than DDM; low critical micelle concentration (CMC) improves image quality [32]. |

| Glycodiosgenin (GDN) | Synthetic detergent increasingly popular for Cryo-EM studies of challenging targets [32] [34]. | Known for its efficacy in stabilizing a variety of membrane proteins, including GPCRs [32] [34]. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye used in BN-PAGE to provide charge for electrophoresis [28] [29]. | Binds to protein surfaces, imparting negative charge; can potentially disrupt some labile protein interactions [29]. |

Workflow Visualizations

Detergent Selection and Troubleshooting Logic

BN-PAGE and Downstream Analysis Workflow

In the analysis of protein complexes, Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and related native techniques serve as a critical bridge between protein separation and functional validation. These methods separate intact protein complexes according to their size, charge, and shape while preserving their native state, thereby maintaining enzymatic activity, subunit interactions, and essential cofactors [36] [14]. This preservation enables researchers to perform in-gel enzymatic assays, a powerful approach for directly linking a separated protein band to its biological function. This technical support center is designed to help you overcome common challenges in these assays, with a consistent focus on the overarching thesis of preventing protein denaturation to obtain biologically relevant functional data.

Core Principles: Why Enzymes Remain Active in the Gel

The Foundation of Native Electrophoresis

Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which uses anionic detergents to linearize proteins and mask their intrinsic charge, native PAGE separates proteins based on a combination of their net negative charge, inherent size, and three-dimensional shape in alkaline running buffers [14] [7]. The key to maintaining activity lies in the omission of denaturing agents. This allows multimeric proteins to retain their quaternary structure and cofactors, such as metal ions, to remain bound [9] [36].

Charge-Shift Molecules: Coomassie vs. SDS

A pivotal distinction lies in the charge-shift molecule used. In standard SDS-PAGE, SDS denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge. In BN-PAGE, the dye Coomassie G-250 binds non-specifically to hydrophobic patches on the protein surface [14]. This binding provides two critical advantages for functional studies:

- It confers a net negative charge even to basic proteins (with high isoelectric points), allowing them to migrate toward the anode.

- It does so while maintaining the protein in its native, folded state, which is a prerequisite for enzymatic function [14].

The following workflow illustrates the critical path for successfully conducting an in-gel activity assay, highlighting steps essential for preventing denaturation.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for In-Gel Activity Assays

FAQ 1: My in-gel activity assay shows no signal. What could be the cause?

Answer: A lack of signal can stem from issues at multiple stages of the experiment.

Protein Denaturation During Preparation:

Loss of Essential Cofactors:

- Cause: Standard electrophoresis buffers may contain EDTA, a chelating agent that can strip essential metal ions from metalloenzymes (e.g., Zn²âº, Cu²âº), rendering them inactive [9].

- Solution: Utilize modified protocols like NSDS-PAGE, which omits EDTA from buffers. Research shows this can increase zinc retention in the proteome from 26% to 98% compared to standard methods [9].

Incompatible Assay Conditions:

- Cause: The reaction buffer components (pH, salt concentration, substrate) may be unsuitable for the specific enzyme after electrophoresis.

- Solution: Optimize the assay buffer composition post-electrophoresis. Ensure the substrate can penetrate the gel matrix and that the product (e.g., a precipitate) is efficiently trapped at the site of activity [36].

FAQ 2: I see high background precipitation throughout my gel, obscuring specific bands. How can I fix this?

Answer: Background precipitation is often related to the assay conditions and can be managed.

- Cause: Non-enzymatic, spontaneous oxidation of the substrate (e.g., diaminobenzidine for Complex IV) can occur throughout the gel [36].

- Solutions:

- Filter and Circulate: Use a custom reaction chamber that continuously circulates and filters the assay medium to remove soluble precipitates and reduce turbidity [36].

- Optimize Substrate Concentration: Increase the dilution or reduce the concentration of the substrate to lower the rate of non-specific background reaction.

- Include Inhibitor Controls: Always run control lanes where a specific enzyme inhibitor (e.g., cyanide for Complex IV, oligomycin for Complex V) is added to the assay buffer. The absence of a band in the inhibited lane confirms the specificity of the activity signal [36].

FAQ 3: My protein complexes appear smeared or show poor resolution on the native gel. What steps can I take?

Answer: Poor resolution typically indicates aggregation or suboptimal electrophoresis conditions.

- Cause: Membrane proteins and hydrophobic complexes are prone to aggregation when not properly solubilized.

- Solution: Ensure adequate solubilization with a compatible non-ionic detergent. The Coomassie G-250 dye in BN-PAGE helps by binding to hydrophobic sites, converting them to negatively charged sites and reducing aggregation [14].

- Cause: Incorrect buffer or gel system.

- Solution: Use the recommended buffer and gel system. For example, NativePAGE Bis-Tris gels are specifically designed for this application and are not interchangeable with buffers for Tris-Glycine or Tris-Acetate gels [38] [14]. The near-neutral pH (~7.5) of the Bis-Tris system is crucial for preserving a wide range of enzymatic activities.

FAQ 4: How can I obtain kinetic data from my in-gel assay instead of just an endpoint measurement?

Answer: Traditional endpoint measurements after gel fixation lack temporal resolution. For kinetics, a continuous monitoring system is required.

- Solution: Implement a system with a reaction chamber that allows for media recirculation and filtering, coupled with time-lapse high-resolution digital imaging [36]. This setup permits the continuous collection of data, enabling the analysis of complex kinetic behaviors such as initial linear rates and lag phases, as demonstrated for mitochondrial Complex V [36].

Quantitative Data and Protocols

Protocol: Standard In-Gel Activity Assay for Mitochondrial Complex IV

This protocol is adapted from studies on mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes (MOPCs) [36].

- Sample Preparation: Solubilize mitochondrial pellets (10-50 µg protein) in a native-compatible buffer containing 50 mM BisTris (pH 7.2), 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 1% dodecyl maltoside. Do not heat. Centrifuge to remove insolubles.

- BN-PAGE: Mix the supernatant with NativePAGE Sample Buffer and 5% G-250 Additive. Load onto a NativePAGE Novex 4-16% Bis-Tris gel. Run with Anode (clear) and Cathode (blue) buffers at 150V for about 90-95 minutes at 4°C [36] [14].

- In-Gel Incubation: Immediately after electrophoresis, incubate the gel in the dark in a solution of 0.05% DAB (diaminobenzidine), 1 mg/mL cytochrome c, and 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0.

- Kinetic Imaging (Optional): Place the gel in a custom chamber with recirculating and filtered assay medium. Capture images at regular intervals using a time-lapse system [36].

- Analysis: Use image processing software to quantify the intensity of the brownish indamine precipitate formed in the Complex IV band over time.

The table below summarizes key quantitative data comparing different electrophoretic methods, highlighting the superiority of native protocols for functional studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Electrophoretic Methods for Functional Analysis

| Method | Key Characteristic | Retention of Zn²⺠in Proteome | Enzymes Retaining Activity (from a 9-enzyme model) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDS-PAGE [9] [7] | Denaturing; uses SDS and heat | ~26% | 0 out of 9 | Analysis of protein size and purity; western blotting |

| BN-PAGE [9] [36] [14] | Native; uses Coomassie G-250 | N/A | 9 out of 9 | Separation of intact complexes; in-gel activity assays |

| NSDS-PAGE [9] | Native; modified SDS-PAGE (no heat, low SDS) | ~98% | 7 out of 9 | High-resolution separation with retained metal cofactors/activity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful in-gel activity assays depend on using the correct reagents and materials designed for native electrophoresis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for In-Gel Activity Assays

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Product / Composition |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Ionic Detergent | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions and activity. | Dodecyl maltoside [36] |

| Coomassie G-250 Additive | Binds proteins, imparting negative charge for electrophoresis without denaturation. Essential for BN-PAGE. | NativePAGE 5% G-250 Sample Additive [36] [14] |

| Specialized Running Buffers | Maintain a pH (~7.5) that is compatible with a wide range of protein stabilities and activities. | NativePAGE Running Buffer & Cathode Buffer Additive [14] |

| Compatible Gel System | Provides the correct matrix and pH environment for native separation. | NativePAGE Novex 4-16% Bis-Tris Gels [38] [14] |

| Activity Assay Substrates | Enzymatic substrates that yield an insoluble, colored precipitate upon reaction. | Diaminobenzidine (DAB) for Complex IV [36]; Lead nitrate/ATP for Complex V ATPase [36] |

| PVDF Membrane | Required for western blotting after NativePAGE. Nitrocellulose binds Coomassie dye too tightly. | PVDF Membrane [14] |

| 1-(4-Ethylphenyl)ethane-1,2-diamine | 1-(4-Ethylphenyl)ethane-1,2-diamine for Research | High-purity 1-(4-Ethylphenyl)ethane-1,2-diamine for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

| C31H26ClN3O3 | C31H26ClN3O3, MF:C31H26ClN3O3, MW:524.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The relationships between the core components in the toolkit and the quality of your experimental output are summarized below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical steps to prevent protein denaturation when preparing samples for Native PAGE?

Protein denaturation during sample preparation can be mitigated by paying close attention to the following:

- Avoid Detergents and Denaturing Agents: Do not use SDS, DTT, or other reducing agents in your sample buffer or gel system, as they disrupt non-covalent interactions and unfold the protein.

- Control Sample Ionic Strength: The ionic strength of your sample should not be higher than 0.1 mmol/L to prevent band deformation and disruption of the electrophoretic field [39].

- Maintain Low Temperature: Keep samples on ice at all times prior to loading to preserve complex integrity and prevent thermal aggregation.

- Pre-run the Gel: A pre-run of the gel (30-60 minutes) under running conditions is preferred to establish a stable pH gradient and remove residual ammonium persulfate (APS) that could oxidize and inactivate proteins [39].

FAQ 2: How does the air-water interface contribute to protein denaturation, and how can I avoid it?

Research has shown that the air-water interface is a hostile environment where proteins can adsorb and partially or completely denature within milliseconds of contact [2]. During plunge-freezing for techniques like cryo-EM, up to 90% of complexes can be damaged at this interface, with unfolded regions facing the air [2].

- Solution: The use of a stable substrate like hydrophilized graphene on EM grids has been shown to completely avoid denaturation by preventing protein contact with the air-water interface [2]. For Native PAGE, while not directly transferable, this underscores the importance of minimizing bubble formation and surface agitation during gel casting and sample loading.

FAQ 3: My protein bands are smeared or show poor resolution. What could be the cause?

Poor band separation, or smearing, is a common issue with several potential causes, which are summarized in the table below.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Sample Overloading | Load less protein into each lane. Validate the optimal amount for each protein-antibody pair [40] [41]. |

| Incorrect Gel Percentage | Use a lower percentage polyacrylamide gel for high molecular weight complexes and a higher percentage for low molecular weight proteins [41]. |

| Protein Aggregation | Ensure proper sample preparation without boiling. Centrifuge samples before loading to pellet any insoluble material [39]. |

| Incomplete Gel Polymerization | Confirm all gel ingredients are fresh and added in correct concentrations, especially TEMED. Use pre-made gels to avoid this issue [41]. |

| Incorrect Buffer System | For Native PAGE, use a high-pH system for acidic proteins and a low-pH system for basic proteins, inverting the cathode and anode for the latter [39]. |

FAQ 4: I observe unexpected or multiple bands in my Native PAGE gel. What does this indicate?

Unlike SDS-PAGE, which separates denatured polypeptides by mass, Native PAGE separates proteins by their native charge, size, and shape. Multiple bands can indicate:

- The Presence of Different Oligomeric States: Your protein complex may exist as a monomer, dimer, trimer, etc.

- Isoforms or Post-Translational Modifications: Different glycosylation or phosphorylation states can alter the protein's migration.

- Stable Protein-Protein Interactions: The bands may represent distinct, native supercomplexes, such as the respirasome (CI, CIIIâ‚‚, CIV) or other assemblies [42] [43]. This is a common and informative finding when studying respiratory complexes.

The following table consolidates key quantitative parameters from experimental protocols to assist in troubleshooting and experimental design.

| Parameter | Optimal Condition / Value | Protocol Context / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Boiling Time | 5 minutes at 98°C | For denaturing SDS-PAGE sample preparation; boiling too long can degrade proteins [41]. |

| Voltage for Gel Running | 100-200 V | For Native PAGE; running outside this range can cause poor separation [39]. |

| Gel Pre-run Time | 30-60 minutes | For Native PAGE; establishes stable pH and removes residual APS [39]. |

| Sample Ionic Strength | ≤ 0.1 mmol/L | For Native PAGE; prevents band deformation [39]. |