Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE: A Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Activity and Functional Recovery for Biomedical Research

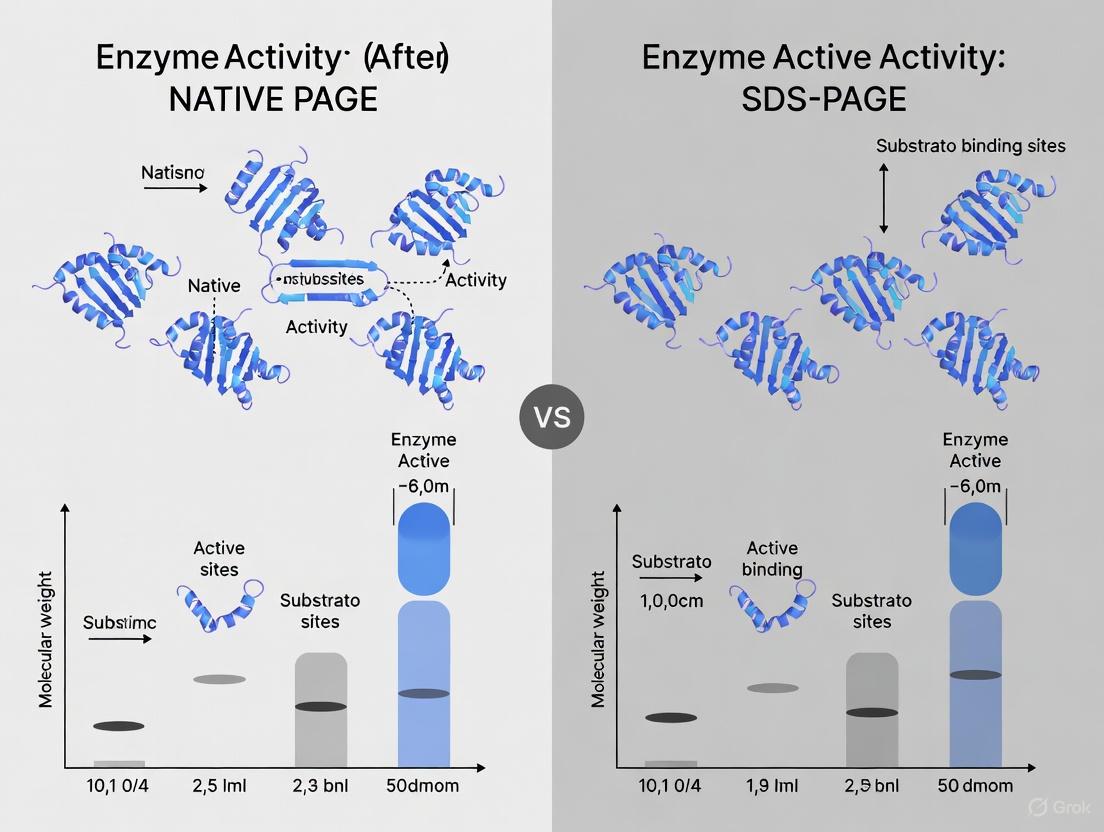

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, focusing on their profound differences in preserving enzyme activity and native protein structure.

Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE: A Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Activity and Functional Recovery for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, focusing on their profound differences in preserving enzyme activity and native protein structure. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the fundamental principles of these techniques, detailing their specific methodologies for applications ranging from basic enzyme characterization to complex functional studies. The content delivers practical troubleshooting guidance and synthesizes experimental data, including insights into hybrid techniques like NSDS-PAGE, to validate the suitability of each method for downstream analyses such as activity assays, metal cofactor retention, and protein-protein interaction studies. The objective is to equip scientists with the knowledge to select the optimal electrophoretic strategy for their specific research goals in enzymology and therapeutic development.

Core Principles: How Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE Differ at a Fundamental Level

Core Principles of Electrophoretic Separation

In the fields of biochemistry and molecular biology, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental technique for protein analysis. Two principal methodologies—Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE—offer divergent approaches for separating proteins based on their distinct physicochemical properties. Native PAGE separates proteins according to their intrinsic size, charge, and shape, preserving their native conformation and biological activity. In contrast, SDS-PAGE employs the denaturing detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate to mask intrinsic protein charges and unfold the protein structure, resulting in separation based almost exclusively on molecular weight [1] [2] [3].

The critical distinction lies in their treatment of protein structure. Native PAGE maintains proteins in their folded, functional state by using non-denaturing conditions without SDS [4]. This allows researchers to study proteins as they exist biologically. Conversely, SDS-PAGE deliberately denatures proteins through a combination of SDS and often heat, linearizing polypeptide chains and obliterating higher-order structures [1] [5]. This fundamental difference in approach dictates their respective applications in research, particularly when analyzing enzyme activity.

Comparative Analysis: Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

Table 1: Fundamental differences between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Criteria | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Size, charge, and shape of native protein [4] [2] | Molecular weight alone [4] [2] |

| Gel Conditions | Non-denaturing [4] [3] | Denaturing [4] [3] |

| SDS Presence | Absent [4] | Present [4] [5] |

| Sample Preparation | Not heated [4] | Heated (typically 70-100°C) [4] [2] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation [1] [4] | Denatured, linearized [1] [5] |

| Biological Activity | Retained post-separation [1] [4] | Lost post-separation [1] [4] |

| Protein Recovery | Possible in functional form [4] [3] | Not recoverable in functional form [4] [3] |

| Primary Applications | Studying protein complexes, oligomerization, and enzymatic function [1] [6] | Determining molecular weight, subunit composition, and purity [1] [7] |

Experimental Evidence: Enzyme Activity Post-Electrophoresis

The defining difference between these techniques becomes most apparent when assessing enzymatic activity after separation. Research consistently demonstrates that the denaturing conditions of SDS-PAGE irrevocably destroy enzyme function, while Native PAGE preserves it, enabling unique downstream analyses.

In-Gel Activity Assays for Functional Analysis

A key application of Native PAGE is the direct detection of enzyme activity within the gel itself. A 2025 study on medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) adapted a high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) method coupled with a colorimetric assay [6]. Following electrophoretic separation, the gel was incubated with the physiological substrate octanoyl-CoA and nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT). Active MCAD oxidizes the substrate, reducing NBT to an insoluble purple formazan precipitate, forming visible bands at the enzyme's location [6]. This method allowed researchers to quantitatively distinguish the activity of functional tetramers from inactive aggregated or fragmented forms of clinically relevant MCAD variants, providing insights impossible to obtain with denaturing methods.

Table 2: Experimental data on metal retention and enzyme activity from comparative PAGE methods

| Experimental Parameter | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zn²⺠Retention in Proteomic Samples | 26% [8] | Not Specified | 98% [8] |

| Active Model Enzymes (from nine tested) | 0 [8] | 9 [8] | 7 [8] |

| Key Functional Takeaway | Denatures proteins, destroying activity and stripping non-covalent cofactors [8] | Preserves native structure and function in most cases [8] [9] | Offers a compromise with high resolution and retained function for many enzymes [8] |

A Modified Compromise: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

Bridging the gap between high-resolution separation and functional preservation, researchers have developed Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE). This method modifies standard SDS-PAGE conditions by omitting EDTA and reducing SDS concentration in the running buffer from 0.1% to 0.0375%, while also eliminating the sample heating step [8]. This approach aims to maintain excellent protein resolution while significantly improving the retention of functional properties. Experimental results demonstrate its effectiveness: Zn²⺠retention in proteomic samples increased from 26% (standard SDS-PAGE) to 98% (NSDS-PAGE), and seven out of nine model enzymes retained their activity post-electrophoresis [8].

Methodology for In-Gel Enzyme Activity Detection

- Electrophoresis: Separate protein samples (e.g., recombinant enzymes or mitochondrial-enriched fractions) using high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE). Clear native conditions are chosen to avoid interference from Coomassie dye in subsequent staining.

- Staining Solution Preparation: Prepare a reaction mixture containing the physiological substrate, 50-100 µM octanoyl-CoA, and 500 µM nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) in an appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0).

- Incubation: Incubate the gel in the staining solution in the dark at room temperature. Purple-colored bands indicating enzymatic activity typically become visible within 10-15 minutes.

- Quantification: Stop the reaction by rinsing the gel with distilled water. Activity bands can be quantified using densitometry, which shows a linear correlation with the amount of loaded protein, enabling quantitative comparisons.

This specialized method allows for the simultaneous determination of molecular weight and activity, even after a denaturing separation.

- SDS-PAGE Separation: Perform standard SDS-PAGE with the protein samples.

- SDS Removal: After electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a renaturing buffer to remove SDS. This step is crucial for the recovery of enzyme activity.

- Two-Step Staining:

- Step 1: Incubate the gel with 2.45 mM NBT in 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) for 20 minutes.

- Step 2: Transfer the gel to a solution containing the previous components plus 28 µM riboflavin and 28 mM TEMED. Incubate for 1 hour in the dark.

- Development: Place the gel in distilled water and expose it to intense light. Active SOD enzymes appear as white (achromatic) bands on a uniform purple background. SOD catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide radicals generated by the light-driven reaction, preventing the reduction of NBT in its vicinity.

Research Reagent Solutions for Native Electrophoresis

Table 3: Essential reagents for native gel electrophoresis and activity assays

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Coomassie Blue G-250 (for BN-PAGE) | Imparts negative charge to proteins, prevents aggregation, enables migration [9] | Can interfere with downstream in-gel activity assays; use Clear Native PAGE for such applications [9] |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside / Digitonin | Mild non-ionic detergents for solubilizing membrane proteins while preserving complexes [9] | Digitonin is milder, ideal for preserving supercomplexes (e.g., respirasomes) [9] |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) | Electron acceptor; reduces to purple formazan precipitate upon enzyme activity [6] [10] | Standard chromogen for in-gel oxidoreductase activity assays |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; provides ionic strength for extraction without disrupting native structure [9] | Helps maintain protein stability during the extraction process |

| Octanoyl-CoA / Specific Substrate | Physiological substrate for the enzyme of interest (e.g., for MCAD) [6] | Using a physiological substrate increases the biological relevance of the activity assay |

| High-Resolution Clear Native Gels | Polyacrylamide matrix for separating native proteins based on charge, size, and shape [6] | Absence of dye prevents interference with colorimetric activity stains |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the critical decision points and corresponding outcomes in the process of selecting and executing a protein electrophoresis method for functional enzyme studies.

Electrophoresis Method Decision Pathway This workflow guides the selection of an electrophoresis method based on research goals, highlighting the divergent functional outcomes for enzyme analysis.

Concluding Synthesis

The choice between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE is not merely technical but fundamental to the biological question being addressed. SDS-PAGE remains the gold standard for determining molecular weight and assessing sample purity, sacrificing all native structure and function in the process [1] [7]. In contrast, Native PAGE and its variants (BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE) are indispensable for probing the functional state of enzymes, analyzing protein-protein interactions within complexes, and identifying structural anomalies in pathogenic variants [1] [6]. The development of hybrid techniques like NSDS-PAGE [8] demonstrates an active effort to overcome the traditional trade-off between resolution and activity, providing researchers with an expanded toolkit for comprehensive protein characterization. For any study where enzymatic function is a primary endpoint, Native PAGE is the unequivocal method of choice, enabling insights into biological mechanisms that denaturing methods cannot provide.

In the comparative analysis of enzyme activity after Native PAGE versus SDS-PAGE, the role of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in protein separation strategy. SDS-PAGE, first developed by Ulrich Laemmli in 1970 and now one of the most cited methods in scientific literature, operates on principles diametrically opposed to native electrophoresis techniques [11] [12]. This detergent-based separation method fundamentally alters protein structure through two synergistic mechanisms: complete denaturation of higher-order structures and masking of intrinsic charge characteristics. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for researchers and drug development professionals selecting appropriate separation techniques for enzyme studies, functional assays, and structural analysis.

Principles of SDS-PAGE

SDS-PAGE separates proteins based almost exclusively on molecular weight by systematically eliminating other variables that influence electrophoretic mobility. The technique achieves this through a carefully orchestrated process that unfolds complex protein structures and standardizes their charge properties [13] [14].

At the molecular level, SDS interacts with proteins through multiple mechanisms. The detergent contains both hydrophobic tails that associate with nonpolar protein regions and ionic head groups that impart negative charge [14]. This amphipathic nature enables SDS to disrupt hydrophobic interactions within protein cores while simultaneously coating the polypeptide chain with negative charges. Approximately 1.4 grams of SDS bind per gram of protein, corresponding to roughly one SDS molecule per two amino acids, creating a uniform charge-to-mass ratio across different proteins [11] [15].

The resulting protein-SDS complexes adopt an elongated, rod-like conformation with similar charge densities but lengths proportional to molecular weight [13] [16]. This structural transformation is essential for accurate molecular weight determination, as the proteins now migrate through the polyacrylamide gel matrix based primarily on size rather than intrinsic charge or three-dimensional structure [14].

SDS Denaturation Mechanisms

Protein Unfolding Pathways

The denaturation process initiated by SDS follows specific molecular pathways that have been elucidated through all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Research indicates that SDS-induced unfolding occurs through two distinct mechanisms where specific interactions of individual SDS molecules disrupt protein secondary structure [16]. The final unfolded state typically features proteins wrapped around SDS micelles in a dynamic "necklace-and-beads" configuration, where the number and location of bound micelles change continuously [16].

Sample Preparation for Denaturation

Standard SDS-PAGE protocols employ multiple denaturation strategies to ensure complete unfolding of protein structures:

SDS Application: Samples are mixed with SDS-containing buffer, typically at concentrations of 0.1-1% SDS, which exceeds the critical micelle concentration of 7-10 mM [11] [17]. At these concentrations, SDS effectively disrupts hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding that maintain secondary and tertiary structures [14].

Reducing Agents: Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol, or other reducing agents are added at concentrations of 10-160 mM to break covalent disulfide bonds between cysteine residues that would otherwise maintain structural integrity [11] [17]. This step is crucial for complete unfolding of proteins with multiple subunits or disulfide-stabilized domains.

Heat Treatment: Samples are heated to 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes to provide thermal energy that disrupts hydrogen bonds and accelerates the denaturation process [11] [12]. The combination of chemical and thermal denaturation ensures proteins are fully linearized before electrophoresis.

Table 1: Standard Protein Denaturation Protocol for SDS-PAGE

| Step | Reagent/Condition | Typical Concentration | Primary Function | Effect on Protein Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | 1-2% (wt/vol) | Charge masking & initial unfolding | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions & hydrogen bonds; confers negative charge |

| 2 | DTT or β-mercaptoethanol | 10-160 mM | Reduction of disulfide bonds | Breaks covalent -S-S- linkages between cysteine residues |

| 3 | Heat treatment | 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes | Acceleration of denaturation | Disrupts hydrogen bonds with thermal energy |

| 4 | EDTA | 1-2 mM | Chelation of metal ions | Inactivates metalloenzymes and prevents proteolysis |

Charge Masking by SDS

Principle of Charge Uniformization

The second critical function of SDS in electrophoresis is to mask the inherent charge differences between proteins. Native proteins carry net charges determined by their amino acid composition and isoelectric points, which vary significantly between different proteins [13] [14]. SDS binding standardizes this variable by imparting a nearly uniform negative charge density along the entire polypeptide backbone [18] [12].

The anionic sulfate groups of SDS create a delocalized negative charge that overwhelms any intrinsic charge characteristics of the protein [14]. This results in a consistent charge-to-mass ratio across different proteins, ensuring that electrophoretic mobility depends primarily on molecular size rather than charge [13]. The extensive SDS coating (approximately one SDS molecule per two amino acid residues) creates a negatively charged "shell" around the denatured polypeptide [11].

Electrophoretic Separation Mechanism

During electrophoresis, the uniformly charged protein-SDS complexes migrate toward the anode when an electric field is applied [18] [14]. The polyacrylamide gel matrix acts as a molecular sieve, retarding larger molecules while allowing smaller polypeptides to migrate more rapidly [12]. This results in separation strictly by molecular size rather than the combined influence of size, shape, and charge that would occur in native conditions.

Comparative Analysis: SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

The fundamental differences in sample preparation between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE directly impact the preservation of enzyme activity and structural integrity. These differences can be quantitatively measured through enzyme activity assays and metal retention studies.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Enzyme Activity and Structural Features After SDS-PAGE vs. Native PAGE

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | Native PAGE | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activity Retention | 0-22% (most enzymes completely inactivated) | 85-100% | Only 2 of 9 model enzymes showed activity after SDS-PAGE vs. 9 of 9 after BN-PAGE [8] |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | 26% Zn²⺠retention | 98% Zn²⺠retention | Metalloenzymes largely lose metal cofactors in SDS-PAGE [8] |

| Quaternary Structure | Dissociated into subunits | Maintains native oligomeric state | Multi-subunit proteins dissociate; separation by subunit weight [1] |

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight only | Size, charge, and shape | SDS masks intrinsic charge and denatures structure [1] [13] |

| Protein Detection | Compatible with staining, western blotting | Compatible with activity staining, functional assays | Enzymes can be detected directly via activity in Native PAGE [1] |

| Typical Applications | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment | Enzyme activity assays, protein-protein interactions | Native PAGE preserves functional properties [1] [8] |

Modified SDS-PAGE Methods

Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE)

Recent methodological developments have sought to bridge the gap between the high resolution of SDS-PAGE and the functional preservation of Native PAGE. A technique called Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) modifies traditional protocols by reducing SDS concentration in running buffers from 0.1% to 0.0375%, eliminating EDTA from sample buffers, and omitting the heating step [8]. This approach maintains excellent protein resolution while significantly improving the retention of enzymatic activity and metal cofactors. Experimental data demonstrates that Zn²⺠retention increases from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% in NSDS-PAGE, with seven of nine model enzymes retaining activity under these modified conditions [8].

Buffer System Variations

Alternative buffer systems have been developed to address specific research needs. The Tris-tricine buffer system provides improved separation of low molecular weight proteins and peptides (0.5-50 kDa) compared to the traditional Tris-glycine system [11]. Continuous buffer systems using Bis-tris at nearly neutral pH (6.4-7.2) offer enhanced gel stability and reduced cysteine modification, though they lack the stacking effect of discontinuous systems [11].

Experimental Protocols

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol for Enzyme Analysis

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with 2× SDS sample buffer (4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 120 mM Tris-Cl pH 6.8, 0.02% bromophenol blue) containing 100 mM DTT [17]. Heat at 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes to denature proteins [11].

Gel Casting: Prepare resolving gel (typically 10-12% acrylamide for most enzymes) with Tris buffer pH 8.8. Layer with isopropanol to create a flat interface. After polymerization, pour stacking gel (4% acrylamide) with Tris buffer pH 6.8 and insert sample comb [11] [14].

Electrophoresis: Load denatured samples and molecular weight markers. Run at constant voltage (100-150 V) using Tris-glycine-SDS running buffer until dye front reaches bottom [12].

Activity Staining (for residual activity): Immediately after electrophoresis, incubate gel in appropriate substrate buffer to detect any remaining enzymatic activity. Compare with identical sample run on Native PAGE [8].

NSDS-PAGE Protocol for Partial Activity Retention

Sample Preparation: Mix protein samples with NSDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% glycerol, 0.0185% Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% Phenol Red, pH 8.5) without heating [8].

Gel Pre-equilibration: Pre-run NuPAGE Novex Bis-Tris gels in ddHâ‚‚O for 30 minutes at 200V to remove storage buffer and unpolymerized acrylamide [8].

Electrophoresis: Run at 200V for 30-45 minutes using NSDS running buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.0375% SDS, pH 7.7) without EDTA [8].

Activity Assay: Transfer proteins to native conditions or assay directly in gel for enzymatic activity [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for SDS-PAGE and Enzyme Activity Studies

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentration | Considerations for Enzyme Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Protein denaturation & charge masking | 1-2% in sample buffer | Complete denaturation destroys most enzyme activity [11] [14] |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | Reduction of disulfide bonds | 10-100 mM | Essential for complete unfolding; prevents refolding [11] [17] |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Gel matrix formation | 4-20% total concentration | Pore size determines separation range [11] [12] |

| TEMED/Ammonium Persulfate | Polymerization catalysts | 0.1% TEMED, 0.1% APS | Initiate free radical polymerization [11] [14] |

| Tris-Glycine Buffer | Electrophoresis running buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine | Most common discontinuous buffer system [11] [15] |

| Coomassie Blue/Silver Stain | Protein visualization | 0.1% Coomassie | Standard detection; does not require enzyme activity [11] [12] |

| Activity Stain Substrates | Enzyme activity detection | Varies by enzyme | Only applicable to Native PAGE or partially denatured enzymes [8] |

Visualization of SDS Mechanisms

The role of SDS in protein denaturation and charge masking establishes SDS-PAGE as an indispensable but functionally destructive separation method. For researchers investigating enzyme activity, the choice between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE represents a fundamental trade-off between resolution and functional preservation. While SDS-PAGE provides unparalleled accuracy in molecular weight determination and high-resolution separation, it achieves this at the cost of enzymatic activity and native structure. Native PAGE maintains functional integrity but offers reduced resolution. The emergence of modified techniques like NSDS-PAGE demonstrates that hybrid approaches can provide intermediate solutions, but the core compromise remains: the very mechanisms that make SDS-PAGE effective for size-based separation—complete denaturation and charge uniformization—are diametrically opposed to the preservation of enzyme activity. Researchers must therefore align their methodological choices with their primary experimental objectives, whether that be structural characterization or functional analysis.

For researchers in drug development and life sciences, the choice of an electrophoretic method is more than a technical decision—it is a strategic one that dictates the type of biological information one can extract. Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a fundamental tool for protein analysis, yet its variants, Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, answer fundamentally different biological questions. The core distinction lies in their treatment of the protein's native state: Native PAGE meticulously preserves the intricate three-dimensional structure, quaternary assemblies, and essential cofactors of proteins, while SDS-PAGE deliberately dismantles these features to focus on molecular weight [1] [4]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of how these techniques impact the study of enzyme activity, offering objective data and methodologies to inform experimental design.

Core Principle: A Tale of Two Techniques

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE and their direct consequences on protein structure and function.

Direct Experimental Comparison: Activity and Cofactor Retention

Theoretical distinctions are borne out by experimental data. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from key studies that directly compare the outcomes of SDS-PAGE, Native PAGE, and modified techniques.

Table 1: Experimental Comparison of Enzyme Activity and Cofactor Retention Across PAGE Methods

| Analysis Method | Key Experimental Findings | Experimental Model | Reference / Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activity Post-Electrophoresis | 7 out of 9 model enzymes retained activity after NSDS-PAGE; all 9 were active after BN-PAGE (a type of Native PAGE); all 9 were denatured and inactive after standard SDS-PAGE. [8] | Model Zn²âº-metalloproteins (e.g., Alcohol Dehydrogenase, Alkaline Phosphatase) | In-gel activity assays |

| Metalloprotein Cofactor Retention | Zn²⺠retention in proteomic samples increased from 26% (Standard SDS-PAGE) to 98% (NSDS-PAGE). [8] | Pig kidney (LLC-PK1) cell proteome | Laser Ablation-Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS) |

| Protein Quaternary Structure Analysis | A protein runs as a 60 kDa band on non-reducing SDS-PAGE but as a 120 kDa band on Native-PAGE, correctly inferring a non-covalent dimer. [19] | Protein isolated from a natural source | Migration comparison against molecular weight standards |

| Post-SDS-PAGE Renaturation | Some monomeric enzymes can be renatured after SDS-PAGE by removing SDS, but oligomeric enzymes composed of identical subunits renature poorly. [20] | Amylases, Dehydrogenases, Proteases | In-situ activity detection in gel after SDS diffusion |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear technical roadmap, here are the detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol 1: Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) for Retaining Functional Properties

This protocol, adapted from PMC4517606, modifies standard SDS-PAGE to preserve certain native features while maintaining high resolution [8].

- Sample Preparation: Mix 7.5 μL of protein sample (5-25 μg) with 2.5 μL of 4X NSDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM Tris base, 10% v/v glycerol, 0.0185% w/v Coomassie G-250, 0.00625% w/v Phenol Red, pH 8.5). Do not heat the sample.

- Gel Pre-run: Pre-run a commercial precast NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris 1.0 mm mini-gel at 200V for 30 minutes in double-distilled Hâ‚‚O to remove storage buffer and unpolymerized acrylamide.

- Electrophoresis: Load the samples and run the gel at a constant 200V for approximately 45 minutes, using a running buffer containing 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, and a reduced SDS concentration of 0.0375% (pH 7.7). Omit EDTA from the running buffer.

- Post-Electrophoresis Analysis: Proteins separated via this method can be analyzed for metal content (e.g., via LA-ICP-MS) or enzymatic activity through in-gel assays.

Protocol 2: In-Gel Enzyme Renaturation After Standard SDS-PAGE

This classic protocol demonstrates that some, but not all, enzymatic activity can be recovered post-denaturation [20].

- Electrophoresis: Perform standard SDS-PAGE as required for your protein of interest.

- SDS Removal: After electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a suitable buffer without SDS to allow the detergent to diffuse out of the gel matrix. This step is critical for renaturation.

- In-Situ Activity Assay: Detect enzyme activity by incubating the gel in a reaction buffer containing the enzyme's specific substrate. The detection is achieved by staining for the resulting product or the remaining substrate.

- Critical Note: The success of renaturation is highly variable. Monomeric enzymes without disulfide bonds are the best candidates, while oligomeric enzymes and some proteases (like trypsin) renature poorly or not at all.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for PAGE-Based Activity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Consideration for Native State |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Strong anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge. | Omitted in Native PAGE; used in reduced concentration (0.0375%) in NSDS-PAGE to partially preserve activity. [8] |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, BME) | Breaks disulfide bonds to fully linearize polypeptides. | Omitted in non-reducing SDS-PAGE and Native PAGE to preserve native disulfide bonds and quaternary structures. [4] [19] |

| Coomassie G-250 | Anionic dye used in Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE). | Imparts a negative charge to proteins for electrophoresis without causing significant denaturation, unlike SDS. [8] |

| Apo-Enzyme | Enzyme without its essential cofactor. | Used in cofactor-directed immobilization studies to demonstrate the critical role of cofactors in enzymatic activity and stability. [21] |

| Functionalized Montmorillonite (FMt) | A nanostructured clay mineral support for enzyme immobilization. | Serves as a model support for co-immobilizing enzymes in their active conformations, highlighting the importance of native state in biocatalysis. [21] |

| (1,5E,11E)-tridecatriene-7,9-diyne-3,4-diacetate | (1,5E,11E)-tridecatriene-7,9-diyne-3,4-diacetate, MF:C17H16O5, MW:300.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (Rac)-Lisaftoclax | (Rac)-Lisaftoclax, MF:C45H48ClN7O8S, MW:882.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Critical Role of Cofactors and Conformation

The preservation of enzymatic activity is intrinsically linked to the integrity of its native structure, which includes not just the polypeptide chain but also non-polypeptide components.

Protein-Derived Cofactors: Many enzymes possess "built-in" or "homemade" cofactors formed via post-translational modifications of their own amino acid residues (e.g., crosslinked Tyr-His pairs, glycine radicals, cysteine-derived pyruvoyl groups) [22]. These intricate structures are integral to the enzyme's architecture and catalytic power. SDS-PAGE disrupts the protein folding essential for maintaining these cofactors, irrevocably destroying activity.

Conformational Equilibrium: Some enzymes, like certain lipases, exist in an equilibrium between a closed (inactive) and an open (active) conformation [23]. The local environment within biomolecular condensates or on solid supports can shift this equilibrium toward the active state by providing a less polar environment or promoting beneficial interactions. This subtle conformational control is lost upon denaturation in SDS-PAGE.

The choice between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE is a choice between studying a protein's identity and its function. SDS-PAGE is an unparalleled tool for determining molecular weight, assessing purity, and analyzing subunit composition. However, if the experimental goal is to understand a protein's biological activity, interrogate its quaternary structure, or investigate its metal cofactor dependency, then Native PAGE is the unequivocal method of choice. The experimental data is clear: the native state—with its folded domains, assembled subunits, and intact cofactors—is not a mere detail but the very essence of enzymatic function. For researchers driving innovation in drug discovery and biocatalysis, designing experiments that preserve this state is paramount.

Functional Enzymes vs. Denatured Polypeptides

In biochemical research, the choice between native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and sodium dodecyl sulfate-PAGE (SDS-PAGE) dictates whether proteins survive analysis as functional biomolecules or become simplified polypeptide chains. This distinction is fundamental for studies requiring functional enzyme activity versus those focused solely on subunit composition or molecular weight. Within a comparative analysis of enzyme activity post-electrophoresis, native PAGE serves as the definitive method for recovering catalytically active enzymes, while SDS-PAGE provides a denaturing environment that yields inactive polypeptides separated by molecular mass [24] [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these techniques, supported by experimental data, to inform strategic methodological choices in research and drug development.

Core Principle Comparison: Preservation vs. Denaturation

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in their treatment of protein structure. Native PAGE employs non-denaturing conditions, preserving the protein's higher-order structure (secondary, tertiary, and quaternary), its bound cofactors, and thus, its biological activity [8] [4]. Separation depends on the protein's intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [24]. In contrast, SDS-PAGE is a denaturing technique. The anionic detergent SDS denatures proteins and binds uniformly along the polypeptide backbone, masking the protein's intrinsic charge and imparting a uniform negative charge-to-mass ratio. A reducing agent like β-mercaptoethanol or DTT is often added to break disulfide bonds, fully unraveling the protein into a random coil. Separation occurs primarily by molecular weight as all proteins migrate toward the anode through a sieving gel matrix [24] [25].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Criteria | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Gel Conditions | Non-denaturing | Denaturing |

| Key Reagents | No SDS or reducing agents [25] | SDS and often reducing agents (DTT, BME) [25] |

| Sample Preparation | Not heated [4] | Heated (typically 70-100°C) [24] [4] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation [4] | Denatured, linearized polypeptides [4] |

| Separation Basis | Combined effect of size, charge, and shape [24] [4] | Molecular mass/weight [24] [4] |

| Functional Recovery | Enzymes retain activity; proteins can be recovered functional [24] [8] [4] | Activity is destroyed; proteins cannot be recovered functional [8] [4] |

| Primary Applications | Studying native structure, subunit composition, and function [24] [4] | Determining molecular weight, checking purity/expression [4] [7] |

Experimental Workflow Comparison

The following diagram contrasts the procedural steps and outcomes of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE.

Key Experimental Data and Quantitative Comparison

Empirical studies directly demonstrate the functional consequences of choosing one method over the other. Research comparing standard SDS-PAGE, Blue-Native (BN)-PAGE, and a modified "Native SDS-PAGE" (NSDS-PAGE) provided clear quantitative data on metal retention and enzyme activity.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Electrophoresis Methods on Enzyme Functionality

| Method | Key Condition Modifications | Zn²⺠Retention in Proteomic Samples | Enzyme Activity Retention (Model Enzymes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard SDS-PAGE | Heated sample with SDS and EDTA [8] | 26% | 0 out of 9 enzymes active [8] |

| BN-PAGE | No SDS or heating; Coomassie dye in cathode buffer [8] | Not Specified | 9 out of 9 enzymes active [8] |

| NSDS-PAGE | No heating, no EDTA; greatly reduced SDS [8] | 98% | 7 out of 9 enzymes active [8] |

The NSDS-PAGE protocol demonstrates that subtle modifications, such as removing EDTA and the heating step while minimizing SDS concentration, can dramatically preserve metalloprotein structure and function while maintaining high-resolution separation [8]. In a separate 2025 study, a high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) in-gel activity assay was used to study Medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD) variants. This method successfully separated active tetramers from other forms and showed a linear correlation between the amount of protein loaded and the resulting enzymatic activity, enabling functional analysis of pathogenic variants [6].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Standard SDS-PAGE (Denaturing)

This protocol is adapted from common commercial systems (e.g., Invitrogen NuPAGE) [8].

- Sample Preparation: Mix 7.5 μL of protein sample with 2.5 μL of 4X LDS sample loading buffer (containing SDS). Heat the mixture at 70°C for 10 minutes [8].

- Gel & Buffer: Use a precast Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 12%). The running buffer is 1X MOPS SDS Buffer (50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7) [8].

- Electrophoresis: Load samples and molecular weight standards. Run at a constant voltage of 200V for approximately 45 minutes at room temperature until the dye front migrates to the gel bottom [8].

Protocol: In-Gel Enzyme Activity Assay (Native)

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study investigating MCAD enzyme activity [6].

- Electrophoresis: First, separate the protein sample using a high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) system, such as a 4-16% gradient gel. This step resolves different oligomeric states of the enzyme without denaturation.

- Activity Staining: After electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a reaction solution containing the enzyme's physiological substrate (e.g., octanoyl-CoA for MCAD) and a colorimetric electron acceptor like nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT).

- Detection: NBT reduction by the active enzyme produces an insoluble, purple-colored diformazan precipitate at the location of the enzyme band. Band intensity can be quantified via densitometry and correlates linearly with enzymatic activity [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of electrophoresis and functional analysis requires specific reagents, each with a critical role.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Electrophoresis Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling separation by mass in SDS-PAGE [24]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) | Cleave disulfide bonds in proteins, ensuring complete denaturation and subunit dissociation in reducing SDS-PAGE [7]. |

| Polyacrylamide Gel | A cross-linked polymer matrix that acts as a molecular sieve. Pore size is determined by the concentration of acrylamide/bis-acrylamide [24]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue Dye | Used in Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) to confer negative charge to proteins without full denaturation, allowing separation of native complexes by mass [8]. |

| TEMED & Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Catalyze the polymerization reaction of acrylamide and bisacrylamide to form the polyacrylamide gel matrix [24]. |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) | A colorimetric electron acceptor used in in-gel activity assays; reduction produces a purple precipitate, visualizing active enzyme bands [6]. |

| Mefenamic Acid-d3 | Mefenamic Acid-d3, MF:C15H15NO2, MW:244.30 g/mol |

| Pyrazinamide-d3 | Pyrazinamide-d3, MF:C5H5N3O, MW:126.13 g/mol |

The choice between native PAGE and SDS-PAGE is not a matter of one technique being superior but of selecting the correct tool for the research question. SDS-PAGE is an unparalleled, high-resolution workhorse for determining molecular weight, assessing sample purity, and analyzing polypeptide composition. Its power lies in its ability to simplify complex protein mixtures into constituent denatured chains. Native PAGE, in its various forms (including BN-PAGE and hrCN-PAGE), is the definitive method for any study where biological function is the endpoint. It is essential for investigating enzyme kinetics, protein-protein interactions, cofactor binding, and the functional impact of genetic variants on multimeric enzymes, providing insights that are completely lost under denaturing conditions [8] [6]. For researchers, particularly in drug development where understanding functional protein mechanisms is paramount, integrating both techniques offers a comprehensive strategy—using SDS-PAGE for analytical characterization and native PAGE for functional validation.

Practical Protocols: When to Use Each Method for Enzyme Analysis

The recovery of functional, active enzymes following polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is a critical consideration in biochemical research and drug development, directly influencing the interpretation of enzymatic activity data. The choice between native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, dictated primarily by research objectives, hinges on their dramatically different sample preparation protocols. These protocols—specifically the use of heating, reducing agents, and detergents—determine whether an enzyme's tertiary and quaternary structures are preserved or denatured. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these sample preparation methods, contextualized within the broader thesis of analyzing post-electrophoresis enzyme activity. The fundamental trade-off is clear: while SDS-PAGE offers high-resolution separation by molecular mass, it typically destroys enzyme activity; native PAGE preserves activity and complex structure but provides lower resolution and separation based on multiple intrinsic protein properties [1] [2] [26].

Core Principles and the Impact of Sample Treatment

Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

The core principle of SDS-PAGE is the complete denaturation of proteins to achieve separation based almost exclusively on molecular weight. This is accomplished through a sample buffer containing Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS), a strong anionic detergent, and reducing agents like Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol. SDS binds to hydrophobic regions of proteins in a constant weight ratio, masking their intrinsic charge and imparting a uniform negative charge [12] [11]. Simultaneously, reducing agents cleave disulfide bonds, disrupting covalent structural linkages. The subsequent heating step (typically 70-100°C) ensures complete unfolding by breaking hydrogen bonds, resulting in linearized polypeptide chains. Consequently, migration through the gel correlates directly with polypeptide chain length [2] [12] [26].

In contrast, native PAGE employs a sample buffer devoid of SDS and reducing agents, and omits the heating step. This non-denaturing approach allows proteins to retain their native conformation, including secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures. Separation occurs based on a combination of the protein's intrinsic net charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [1] [4] [2]. This preservation of structure is a prerequisite for detecting enzymatic activity after electrophoresis.

Visualizing the Divergent Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the critical differences in the sample preparation workflows for Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE, and their direct consequences for enzyme structure and function.

Comparative Experimental Data and Methodologies

Quantitative Comparison of Sample Preparation and Outcomes

The table below summarizes the direct comparison of key sample preparation variables and their functional consequences, supported by experimental data.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Sample Preparation Components and Outcomes

| Component | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Heating | Not applied [4] [26] | Applied (typically 70-100°C for 5-10 min) [12] [11] |

| Reducing Agents | Absent [4] [26] | Present (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) to break disulfide bonds [12] [11] |

| Detergents | Absent (or mild, non-ionic) [4] [26] | Present (SDS, anionic) for uniform charge and denaturation [12] [11] |

| Protein State | Native, folded conformation [1] [2] | Denatured, linearized polypeptides [2] [12] |

| Enzyme Activity Post-Electrophoresis | Retained for functional assays [8] [6] | Destroyed [8] [26] |

| Key Experimental Evidence | 7 of 9 model Zn²⺠enzymes retained activity after NSDS-PAGE (modified native method) [8] | All 9 model enzymes were denatured and inactive after standard SDS-PAGE [8] |

| Metal Cofactor Retention | High (98% Zn²⺠retention in NSDS-PAGE) [8] | Low (26% Zn²⺠retention in standard SDS-PAGE) [8] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate how these principles are applied in practice, detailed methodologies for key experiments are provided below.

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol (Denaturing)

- Sample Buffer Composition: Tris-HCl or Tris-Glycine buffer, 1-2% SDS (w/v), 5% β-mercaptoethanol or 10-100 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue) [12] [11].

- Sample Preparation: Protein sample is mixed with the SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The mixture is heated at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [12] [11].

- Electrophoresis: Samples are loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-20% gradient) and run at constant voltage (100-150V) until the dye front reaches the bottom [12].

High-Resolution Clear Native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) Protocol for In-Gel Activity

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study on medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), highlights the preservation of quaternary structure and activity [6].

- Sample Buffer Composition: 50 mM BisTris, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.001% Ponceau S, pH 7.2. No SDS or reducing agents are used [8] [6].

- Sample Preparation: Protein sample is mixed with native sample buffer without heating. For membrane proteins, mild non-ionic detergents like n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside or digitonin may be used for solubilization while preserving complexes [6] [9].

- Electrophoresis: Samples are loaded onto a high-resolution clear native gel (e.g., 4-16% gradient). Electrophoresis is performed at a constant voltage (e.g., 150V) at 4°C to maintain protein stability [4] [6].

- In-Gel Activity Assay: Following electrophoresis, the gel is incubated in a reaction mixture containing the enzyme's physiological substrate (e.g., octanoyl-CoA for MCAD) and a colorimetric electron acceptor like nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT). Active enzymes produce an insoluble purple formazan precipitate at their migration position [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogues key reagents used in these electrophoretic techniques, explaining their critical functions in sample preparation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function in SDS-PAGE | Function in Native PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins; confers uniform negative charge [12] [11] | Typically omitted to preserve native structure [26] |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) / β-Mercaptoethanol | Reduces disulfide bonds; disrupts quaternary structure [12] [11] | Typically omitted to preserve native disulfide bonds [26] |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye | Not used in sample buffer | Used in BN-PAGE to impart charge shift and improve protein solubility [9] |

| Glycerol | Adds density to sample for easy well loading [12] | Adds density to sample for easy well loading [8] |

| Tracking Dye (e.g., Bromophenol Blue) | Visualizes migration front during electrophoresis [11] | Visualizes migration front (e.g., Phenol Red) [8] |

| Mild Detergents (e.g., Dodecyl Maltoside) | Not used for sample denaturation | Solubilizes membrane proteins without dissociating complexes [6] [9] |

| Z-Vdvad-afc | Z-Vdvad-afc, MF:C39H45F3N6O13, MW:862.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ddATP trisodium | ddATP trisodium, MF:C10H13N5Na3O11P3, MW:541.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Concepts: The Emergence of NSDS-PAGE

Recent methodological advancements seek to bridge the gap between the high resolution of SDS-PAGE and the functional preservation of native PAGE. Research has led to the development of Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), a hybrid approach that modifies standard denaturing conditions. In NSDS-PAGE, SDS is not fully removed but its concentration in the running buffer is drastically reduced (e.g., from 0.1% to 0.0375%), and EDTA is deleted. Crucially, the sample is prepared without heating and without EDTA in the sample buffer [8].

This modified approach had a profound effect on metalloenzyme integrity: Zn²⺠retention in proteomic samples increased from 26% (standard SDS-PAGE) to 98% (NSDS-PAGE). Furthermore, seven out of nine model enzymes, including four Zn²âº-proteins, retained their activity after NSDS-PAGE separation, whereas all nine were denatured during standard SDS-PAGE [8]. This demonstrates that strategic adjustments to heating, detergent concentration, and chelating agents can significantly alter experimental outcomes, enabling high-resolution separation without complete functional loss.

The contrast in sample preparation between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE is not merely a technical choice but a fundamental decision that dictates the biological relevance of the data obtained. The use of heating, reducing agents, and the anionic detergent SDS is deliberately designed to dismantle protein structure for molecular weight analysis, irrevocably destroying enzyme activity. Conversely, their omission in native PAGE is essential for studying native conformation, protein-protein interactions, and, most critically, enzymatic function.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this comparison underscores that any thesis on post-electrophoresis enzyme activity must be framed by these initial sample preparation steps. The selection of the method should be driven by the primary research question: SDS-PAGE for protein size, purity, and subunit composition; Native PAGE for function, activity, and complex analysis. The emergence of modified techniques like NSDS-PAGE offers a promising avenue for achieving a balance, allowing for more nuanced experimental designs in functional proteomics and biomarker discovery.

Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) is a foundational technique in biochemistry for separating protein mixtures. The choice between its two primary forms—Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE—fundamentally shapes experimental outcomes, influencing everything from separation resolution to the preservation of biological function. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of the gel composition and running conditions for these two techniques, contextualized within research aimed at analyzing and comparing enzyme activity post-electrophoresis.

Core Principles and Separation Mechanisms

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in the state of the protein during separation.

- Native PAGE separates proteins in their natural, folded conformation. The gel matrix acts as a sieve, meaning migration is influenced by the protein's size, intrinsic charge, and three-dimensional shape [1] [2]. This allows for the analysis of functional, active proteins and their complexes [1].

- SDS-PAGE employs the ionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to denature proteins. SDS binds uniformly to the polypeptide backbone, masking the protein's intrinsic charge and conferring a uniform negative charge. It also unfolds the proteins into linear chains. Consequently, separation occurs almost exclusively based on polypeptide molecular weight [1] [2] [11].

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences in sample preparation and separation mechanics between the two methods.

Gel Composition: A Detailed Comparison

The gel composition is critical for achieving optimal separation. Both techniques typically use a discontinuous system with a stacking gel and a resolving gel, but their chemical compositions differ.

Table 1: Comparative Gel Composition for Native PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

| Component | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide Concentration (Resolving Gel) | Varies by target protein size (e.g., 8-12%) [2] | Varies by target protein size (e.g., 10-20%) [2] | Determines pore size. Higher % for better resolution of smaller proteins. |

| Stacking Gel | Often used, lower % acrylamide (e.g., 4%) [11] | Standard, lower % acrylamide (e.g., 4-6%) [11] | Concentrates proteins into a sharp band before entering the resolving gel. |

| Resolving Gel Buffer | Varied, often Tris-based, pH ~8.8 [11] | Tris-HCl, pH ~8.8 [11] | Creates the basic pH environment for separation. |

| Stacking Gel Buffer | Varied, often Tris-based, pH ~6.8 [11] | Tris-HCl, pH ~6.8 [11] | Creates a pH discontinuity for the stacking effect. |

| Denaturing Agent (SDS) | Absent [1] | Present (0.1% in gels and buffers) [11] | SDS denatures proteins and provides uniform negative charge. Its absence is key to Native PAGE. |

| Reducing Agents (e.g., DTT) | Absent [7] | Often present in sample buffer (e.g., 10-100 mM DTT) [7] [11] | Breaks disulfide bonds to fully denature proteins into subunits. |

Running Conditions and Buffer Systems

The electrophoresis conditions are tailored to maintain the desired protein state and ensure proper migration.

Table 2: Comparative Running Conditions and Buffers

| Parameter | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE | Function and Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine, pH ~8.3-8.8, without SDS [2] [11] | Tris-Glycine, pH ~8.3-8.8, with SDS (0.1%) [2] [11] | Conducts current. SDS in the buffer maintains protein denaturation in SDS-PAGE. |

| Sample Buffer | Non-denaturing, often with glycerol and a tracking dye [19] | Laemmli buffer: contains SDS, glycerol, tracking dye, and often a reducing agent [11] | Prepares sample for loading. Denaturation is critical for SDS-PAGE but avoided in Native PAGE. |

| Sample Preparation | Mixed with buffer, not heated (or heated mildly) [2] | Heated to 95°C for 5 minutes [11] | Heating ensures complete denaturation and SDS binding in SDS-PAGE. |

| Voltage / Current | Lower voltages; often run in cold room or with cooling [2] [27] | Standard voltage (e.g., 100-150V for mini-gels) [11] [27] | Native PAGE is more sensitive to heat to prevent denaturation. High heat can cause band distortion ('smiling') in both [27]. |

| Key Consideration | Maintain native state; pH extremes can denature proteins [2] | Ensure complete denaturation; improper SDS binding leads to poor resolution [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Activity Studies

The following protocols are generalized for comparing enzyme activity after electrophoresis.

Protocol for Native PAGE Followed by In-Gel Activity Assay

This protocol is designed to preserve enzymatic function throughout the process.

- Step 1: Gel Casting. Prepare a native polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 8% resolving gel, 4% stacking gel) using buffers without SDS or reducing agents [1].

- Step 2: Sample Preparation. Dialyze protein samples into a non-denaturing buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl). Mix with native sample buffer without heating [2].

- Step 3: Electrophoresis. Load samples and run the gel in native running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine, no SDS) at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-125V) in a cold room (4°C) or with active cooling to minimize heat-induced denaturation [2] [27].

- Step 4: In-Gel Activity Staining. After electrophoresis, carefully remove the gel from its plates.

- Incubate the gel in an appropriate substrate solution for the target enzyme (e.g., a chromogenic or fluorogenic substrate) under optimal pH and temperature conditions.

- A positive enzymatic reaction will produce a colored or fluorescent band at the location of the active enzyme [1].

- Step 5: Analysis. Document results and compare band intensities and migration positions between samples.

Protocol for SDS-PAGE and Post-Electrophoresis Analysis

This protocol denatures proteins for molecular weight analysis but is incompatible with in-gel activity assays.

- Step 1: Gel Casting. Prepare an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (e.g., a 12% resolving gel, 4% stacking gel) containing 0.1% SDS in both gels and the running buffer [11].

- Step 2: Sample Preparation. Mix protein samples with 2X Laemmli sample buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., DTT). Heat the samples at 95°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [11].

- Step 3: Electrophoresis. Load samples and a molecular weight marker. Run the gel in SDS-running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS) at a constant voltage (e.g., 150V for a mini-gel) until the dye front reaches the bottom [11] [27].

- Step 4: Protein Detection.

- Western Blotting: For specific detection, transfer proteins to a membrane and probe with an enzyme-specific antibody. While this detects the presence of the protein, it does not confirm activity, as the protein is denatured [1].

- Gel Staining: Use Coomassie Blue or silver stain to visualize the total protein profile and assess subunit molecular weight and purity [11].

- Step 5: Analysis. Compare banding patterns and molecular weights. Note that enzyme activity is lost due to denaturation [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked polyacrylamide gel matrix. | Yes | Yes |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Ionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge. | No | Yes [1] [2] |

| APS & TEMED | Catalyst (APS) and stabilizer (TEMED) for free-radical polymerization of the gel. | Yes | Yes [11] |

| DTT or β-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds. | No (typically) | Yes (for reducing conditions) [7] [11] |

| Tris-based Buffers | Maintain pH during gel polymerization and electrophoresis. | Yes | Yes [11] |

| Coomassie Blue/Silver Stain | Dyes for visualizing proteins in the gel after electrophoresis. | Yes | Yes [11] |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Standard proteins of known size for estimating molecular weight. | Limited utility | Essential [2] |

| Sphingolactone-24 | Sphingolactone-24, MF:C18H29NO4, MW:323.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Stambp-IN-1 | Stambp-IN-1, MF:C27H28N4O4S, MW:504.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The choice between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE is dictated by the research objective. For studies focused on enzyme activity, protein-protein interactions, or native conformation, Native PAGE is the indispensable tool, as it preserves the protein's biological function. Conversely, for determining subunit molecular weight, assessing sample purity, or analyzing denatured proteins for western blotting, SDS-PAGE provides superior resolution and simplicity. Understanding their distinct gel compositions and running conditions enables researchers to select the optimal technique and accurately interpret the resulting data for their specific application in drug development and life science research.

Activity Staining with Native PAGE vs. Purity/Weight Check with SDS-PAGE

In the realm of protein biochemistry, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) serves as a foundational technique, with Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE representing two fundamental approaches with distinct applications. Within the context of enzyme research, the choice between these methods dictates whether the outcome will be functional insights or structural characterization. Native PAGE separates proteins in their folded, native state, preserving enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions, and cofactor binding capabilities. Conversely, SDS-PAGE denatures proteins into uniform linear chains, enabling precise molecular weight determination and assessment of sample purity but at the cost of biological function [1] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these techniques, focusing on their application for in-gel activity staining versus purity and molecular weight checks, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols.

Core Principle and Application Comparison

The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in their treatment of protein structure. Native PAGE employs non-denaturing conditions, allowing proteins to migrate based on a combination of their intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape [2]. This preservation of native conformation is precisely what enables the retention of enzymatic function for subsequent activity assays directly within the gel matrix [6].

SDS-PAGE, however, relies on the powerful anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which comprehensively denatures proteins and masks their intrinsic charge. By binding to the polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio, SDS confers a uniform negative charge, ensuring that separation occurs almost exclusively based on polypeptide molecular weight [1] [2]. This makes it the premier technique for assessing protein purity and subunit molecular weight.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE

| Feature | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded structure preserved [1] | Denatured, linearized subunits [1] |

| Separation Basis | Net charge, size, and 3D shape [2] | Primarily molecular mass of polypeptides [2] |

| Key Reagents | Coomassie G-250 (in BN-PAGE), no SDS [8] | SDS, reducing agents (e.g., DTT) [7] |

| Enzymatic Activity | Preserved; suitable for in-gel activity staining [6] | Destroyed by denaturation [8] |

| Quaternary Structure | Maintained (oligomers, complexes) [19] | Disrupted into constituent subunits [1] |

| Primary Application | Studying functional protein complexes, enzyme activity, protein-protein interactions [1] [6] | Determining molecular weight, assessing sample purity, subunit composition [2] [29] |

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Data

The functional and structural trade-offs between these methods are quantifiable. Research has demonstrated that Native PAGE protocols can retain the enzymatic activity of most model enzymes. A study on a modified Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) method showed that seven out of nine model enzymes, including four zinc-binding proteins, retained activity after separation, whereas all nine were denatured and inactivated during standard SDS-PAGE [8]. Furthermore, the retention of bound metal ions—critical for the function of many metalloenzymes—increased from 26% in standard SDS-PAGE to 98% under the milder NSDS-PAGE conditions [8].

From an analytical resolution perspective, SDS-PAGE excels in comparative quantitation. In a comparative study of human bronchial smooth muscle cell proteins, SDS-PAGE coupled with LC-MS/MS enabled the assignment and quantitation of 2,552 proteins from a supernatant fraction, proving highly effective for visualizing quantity differences between samples [30]. While not directly quantifiable as purity, the presence of a single, sharp band on an SDS-PAGE gel is a standard indicator of a homogeneous protein sample [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Experimental Outcomes from Comparative Studies

| Experimental Metric | Native PAGE Performance | SDS-PAGE Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activity Retention | 7 out of 9 model enzymes remained active [8] | 0 out of 9 model enzymes remained active [8] |

| Metalloprotein Cofactor (Zn²âº) Retention | Up to 98% metal ion retention [8] | ~26% metal ion retention [8] |

| Number of Proteins Assigned in Proteomic Study | 4,323 proteins from supernatant fraction [30] | 2,552 proteins from supernatant fraction [30] |

| Effect on Protein Complexes | Maintains homo-oligomeric states (e.g., tetramers) [6] | Disassembles complexes into monomeric subunits [1] |

Experimental Protocol: In-Gel Enzyme Activity Staining after Native PAGE

The following protocol, adapted from a study on medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), details how to perform an in-gel activity assay [6].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the protein sample (recombinant protein or mitochondrial-enriched fraction) in a non-denaturing buffer without SDS or reducing agents. A typical buffer may contain 50 mM BisTris (pH 7.2) and 50 mM NaCl [8].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load the sample onto a high-resolution clear native or blue native polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4-16% gradient). Conduct electrophoresis at a constant voltage (e.g., 150V) with appropriate anode and cathode buffers, keeping the apparatus cool to prevent denaturation [2] [6].

- Activity Staining Incubation: Following electrophoresis, gently incubate the gel in a reaction mixture containing:

- Physiological Substrate: e.g., Octanoyl-CoA for MCAD.

- Electron Acceptor: Nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), which upon reduction forms an insoluble purple formazan precipitate.

- Coupling Agent: Phenazine methosulfate (PMS) or similar to facilitate electron transfer.

- Detection: Monitor the gel for the development of purple bands indicating enzymatic activity. The reaction can be stopped by transferring the gel to a fixing solution like 10% acetic acid. Activity can be quantified by densitometric analysis of the band intensity [6].

Experimental Protocol: Protein Purity and Molecular Weight Check with SDS-PAGE

This standard protocol is used to validate protein purity and estimate molecular weight [2] [29].

- Sample Denaturation: Mix the protein sample with an SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent like dithiothreitol (DTT). A common buffer is Laemmli buffer. Heat the mixture at 70-100°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation and reduction of disulfide bonds [2] [7].

- Gel Preparation and Loading: Cast or use a pre-cast polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 12% Bis-Tris) with a stacking gel. Load the denatured samples into the wells alongside a molecular weight marker (protein ladder) [29].

- Electrophoresis: Assemble the gel apparatus and submerge it in a running buffer containing SDS (e.g., MOPS-SDS buffer). Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 200V) until the dye front reaches the bottom.

- Staining and Visualization: After electrophoresis, stain the gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, SYPRO Ruby, or silver stain to visualize the protein bands. Coomassie is common for general purposes, while silver staining offers higher sensitivity [29].

- Analysis: A pure protein sample will appear as a single, sharp band at the expected molecular weight. Multiple bands indicate the presence of contaminants, proteolytic fragments, or other isoforms. Purity can be quantified using densitometry software to compare the intensity of the target band to the total intensity of all bands in the lane [29].

Workflow and Logical Decision Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for choosing between Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE based on research objectives, and outlines their respective workflows leading to distinct analytical endpoints.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE experiments relies on a set of key reagents, each with a specific function.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for PAGE Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denatures proteins and confers uniform negative charge for separation by size in SDS-PAGE [2]. | Critical for accurate molecular weight determination. |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked porous gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [2]. | Pore size is determined by the concentration; affects resolution range. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) | Breaks disulfide bonds in reducing SDS-PAGE, ensuring complete unfolding [7]. | Omitted in non-reducing SDS-PAGE to study disulfide-linked complexes. |

| Coomassie Blue Stains | Binds non-specifically to proteins for visualization after electrophoresis [29]. | Common for general detection; offers good balance of sensitivity and ease. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A mixture of proteins of known sizes for estimating the molecular weight of unknown proteins [2]. | Essential for calibrating the gel and interpreting results. |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) | A tetrazolium salt that acts as an electron acceptor in activity stains, forming a colored precipitate [6]. | Enables visualization of enzymatic activity in native gels. |

In the study of protein complexes, the choice of electrophoretic technique dictates the type of information that can be obtained. While SDS-PAGE denatures proteins into their constituent polypeptides for molecular weight separation, it obliterates higher-order structure and function [4]. Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (Native PAGE) encompasses techniques designed to separate proteins under non-denaturing conditions, preserving their native conformation, enzymatic activity, and protein-protein interactions [4] [31]. Among these, Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) and Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) have emerged as pivotal tools for the analysis of large, multi-subunit complexes, particularly those embedded in membranes [32] [33]. Within the context of comparative analysis of enzyme activity after native PAGE versus SDS-PAGE, these techniques are indispensable. SDS-PAGE inevitably destroys enzymatic function, whereas BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE provide a platform for isolating intact, catalytically active complexes, enabling direct functional studies immediately following separation [31] [8]. This guide provides a detailed objective comparison of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE, focusing on their performance in separating protein complexes and analyzing their activity.

Fundamental Principles and Separation Mechanisms

The core principle of both BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE is to separate protein complexes based on their native size, charge, and shape, rather than the molecular weight of denatured subunits [4]. This is achieved by using mild, non-ionic detergents for solubilization and alternative methods to impart charge for electrophoresis.

- BN-PAGE relies on the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250 to confer a negative charge onto the surface of protein complexes. This dye binds to hydrophobic protein patches, provides a uniform charge shift for electrophoretic mobility toward the anode, and suppresses aggregation during the run [33] [34]. The result is a high-resolution separation where the migration distance is inversely proportional to the complex's native mass.

- CN-PAGE represents a variation where Coomassie Blue is omitted from the sample and is present only at a lower concentration in the cathode buffer, or is replaced entirely by mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents to impose the necessary charge shift [31] [32] [35]. This "clearer" environment is beneficial for downstream applications sensitive to the presence of the blue dye.

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences and common applications between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE.

Comparative Performance Analysis: BN-PAGE vs. CN-PAGE

The choice between BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE involves trade-offs between resolution, enzymatic activity compatibility, and suitability for specific complexes. The following table summarizes the core operational differences and performance characteristics of the two techniques, providing a basis for experimental selection.

Table 1: Direct comparison of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE techniques

| Feature | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Key Principle | Coomassie Blue dye binds proteins, providing negative charge and preventing aggregation [33] [34]. | Mixed anionic/neutral detergent micelles impose charge; milder dye use or none [31] [32]. |

| Resolution | High. Provides sharp bands and reliable mass determination due to uniform charge-shift [8] [34]. | Lower. Separation depends on both mass and intrinsic charge, can cause band broadening [32]. |

| In-Gel Activity Assays | Good, but Coomassie can inhibit some enzymes (e.g., Complex IV) [32] [35]. | Excellent. Lack of dye interference allows for more sensitive and reliable activity detection [31] [35]. |

| Supercomplex Analysis | Excellent with mild detergents like digitonin [33] [34]. | Suitable, but lower resolution can be a limitation [32]. |

| Visualization | Blue bands during separation [36]. | Colorless/transparent bands during separation [31]. |

| Best For | High-resolution separation, complex stability, mass analysis, and western blotting [37] [33]. | Sensitive in-gel activity assays where dye interference is a concern [31] [32]. |

Quantitative data from direct comparisons further illuminates the performance differences. A study evaluating the retention of enzymatic activity and metal cofactors after electrophoresis demonstrated the clear advantage of native techniques over denaturing methods.

Table 2: Quantitative comparison of enzymatic activity and metal retention across PAGE methods

| Performance Metric | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Activity Retention | 0/9 model enzymes active [8]. | 9/9 model enzymes active [8]. | Comparable to BN-PAGE for many complexes [31]. | 7/9 model enzymes active [8]. |

| Zinc Metalloprotein (Zn²âº) Retention | ~26% [8]. | Data not explicitly quantified in results. | Data not explicitly quantified in results. | ~98% [8]. |

| Complex IV In-Gel Activity Staining | Not applicable. | Less sensitive due to dye interference [32]. | More sensitive, no dye interference [32]. | Not applicable. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Core Protocol for BN-PAGE

The following step-by-step protocol, adapted from established methodologies, is used for the high-resolution separation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes and other protein assemblies [33] [36].

Sample Preparation (Mitochondrial Extract):

- Sediment mitochondria (e.g., 0.4 mg) and resuspend in 40 µL of ice-cold extraction buffer (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors [36].

- Add 7.5 µL of 10% n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (or digitonin for supercomplex analysis) to solubilize membranes. Mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [34] [36].

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 72,000 x g) for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material [36].

- Collect the supernatant and add 2.5 µL of 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [36].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Use a gradient gel (e.g., 4–16% or 6–13% acrylamide) to resolve a broad range of complex sizes [38] [36].

- Load the prepared samples. The cathode buffer contains 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250, while the anode buffer contains none.

- Run electrophoresis at 4°C to maintain complex stability. Start with a low voltage (e.g., 100 V) until samples enter the stacking gel, then increase to 150–500 V for the separation, continuing until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel [38] [36].

In-Gel Enzyme Activity Assay for Complex V (ATP Synthase)

This protocol, validated with enhancements for improved sensitivity, allows direct visualization of ATP hydrolysis activity in BN-PAGE or CN-PAGE gels [32] [35].

- Post-Electrophoresis Incubation: After BN-/CN-PAGE, quickly rinse the gel with distilled water.

- Reaction Mixture: Incubate the gel in the dark at room temperature in a solution containing: 35 mM Tris-HCl, 270 mM glycine, 14 mM MgSO₄, 0.2% Pb(NO₃)₂, and 8 mM ATP [31] [35].

- Reaction Monitoring: Complex V activity hydrolyzes ATP, releasing phosphate that precipitates with lead to form a white lead phosphate precipitate at the location of the Complex V band [31].

- Termination and Enhancement: Once bands are visible, stop the reaction by rinsing with water. An enhancement step using 1% ammonium sulfide can be applied to convert the precipitate to brown lead sulfide for markedly improved sensitivity and contrast [32].

- Quantification: Document the gel with digital imaging. Kinetic analysis can be performed by continuous monitoring with time-lapse photography if a specialized chamber with media circulation and filtering is available [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE relies on a specific set of reagents, each serving a critical function in the separation process.

Table 3: Essential reagents for BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Mild Non-Ionic Detergents | n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, Digitonin, Triton X-100 [33] [34]. | Solubilize membrane lipid bilayers to release protein complexes without disrupting protein-protein interactions. |

| Charge-Shift Agents | Coomassie Blue G-250 (BN-PAGE), Mixed anionic/neutral detergents (CN-PAGE) [31] [33]. | Impart a negative charge to the solubilized complexes, enabling their migration toward the anode during electrophoresis. |

| Solubilization Buffer Components | 6-Aminocaproic acid, Bis-Tris, Protease inhibitors (PMSF, leupeptin, pepstatin) [33] [36]. | Provide a suitable ionic environment (low conductivity), pH control, and prevent proteolytic degradation during sample preparation. |

| In-Gel Activity Assay Reagents | ATP, Pb(NO₃)₂, 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) [31] [32]. | Serve as substrates and detection agents for visualizing enzymatic activity directly within the native gel. |

| 6,7-Dimethylquinoxaline-2,3-dione | 6,7-Dimethylquinoxaline-2,3-dione|RUO|Research Chemical |

BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE are complementary techniques that form a cornerstone in the functional analysis of protein complexes. The experimental data and protocols presented in this guide provide a framework for making an informed choice.