Mastering SDS-PAGE for Western Blotting: A Complete Guide to Optimal Sample Preparation and Separation

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of SDS-PAGE in Western blotting sample preparation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Mastering SDS-PAGE for Western Blotting: A Complete Guide to Optimal Sample Preparation and Separation

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the critical role of SDS-PAGE in Western blotting sample preparation for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles of protein separation by molecular weight, step-by-step methodological protocols for gel electrophoresis, systematic troubleshooting for common issues like smearing and poor transfer, and essential validation techniques using controls and markers. The article synthesizes established knowledge with practical optimization strategies to ensure reproducible, high-quality results in protein analysis for biomedical research.

SDS-PAGE Fundamentals: The Science Behind Protein Separation

In western blotting and other protein analysis techniques, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) plays an indispensable role by fundamentally modifying the physical properties of proteins to enable separation based on molecular weight. This anionic detergent performs two critical functions: it denatures complex protein structures into linear polypeptides and imparts a uniform negative charge to all proteins, effectively masking their intrinsic electrical charges [1] [2] [3]. This transformation is fundamental to SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), ensuring that proteins migrate through the gel matrix at rates determined solely by their molecular size rather than their native charge or three-dimensional conformation [4]. Within the context of western blotting sample preparation, this principle guarantees that the electrophoretic separation accurately reflects protein size, which is crucial for subsequent identification and analysis using specific antibodies.

The Molecular Mechanism of SDS Action

Charge Uniformization Through SDS Binding

SDS molecules interact with protein structures in a highly consistent and predictable manner. The detergent binds to the protein backbone at an approximate ratio of 1.4 grams of SDS per 1 gram of protein, creating a negatively charged micelle-like structure around the polypeptide chain [2] [4]. Each SDS molecule contributes a sulfate group with a strong negative charge, effectively overwhelming any positively or negatively charged amino acid residues that constitute the native protein [3]. This extensive SDS coating ensures that all proteins in a mixture carry a uniform negative charge density, meaning the charge-to-mass ratio becomes essentially identical across different protein species [1] [4]. Consequently, when subjected to an electric field during electrophoresis, all proteins migrate toward the positive anode at rates determined exclusively by their ability to navigate the gel matrix pores, which correlates directly with molecular size [2].

Protein Denaturation and Linearization

The denaturing capability of SDS arises from its amphipathic molecular structure, featuring both a hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail and a hydrophilic sulfate head group [3]. The hydrophobic regions of SDS molecules interact strongly with nonpolar segments of proteins, while the ionic components disrupt hydrogen bonds and other non-covalent interactions that maintain secondary and tertiary structures [2] [3]. This combined action effectively unfolds native protein conformations into random coil structures, eliminating variations in molecular shape that would otherwise influence migration through the gel matrix [4]. For complete linearization, especially in proteins with disulfide bridges, reducing agents such as Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (BME) are added to break covalent bonds between cysteine residues, ensuring all proteins assume similar linear configurations [3] [5]. The resulting polypeptide-SDS complexes are linear molecules approximately 18 Angstroms wide with lengths proportional to their molecular weights, creating ideal conditions for molecular weight-based separation [4].

Diagram 1: Molecular mechanism of SDS action on proteins, showing transformation from native folded state to linear SDS-protein complex with uniform charge.

Quantitative Data on SDS-PAGE Separation

Gel Composition and Molecular Weight Separation Ranges

The polyacrylamide gel matrix serves as a molecular sieve, with its pore size determining the effective separation range for proteins of different sizes. The table below summarizes the relationship between acrylamide concentration and separable molecular weight ranges:

Table 1: Acrylamide Concentrations and Optimal Protein Separation Ranges [4]

| Acrylamide Percentage (%) | Effective Separation Range (kDa) |

|---|---|

| 7% | 50 - 500 kDa |

| 8 - 15% | 10 - 250 kDa |

| 10% | 20 - 300 kDa |

| 12% | 10 - 200 kDa |

| 12.5% | For Rab GTPases |

| 15% | 3 - 100 kDa |

| Gradient (5-20%) | Proteins with subtle MW differences |

For specific applications, gel composition can be optimized further. For instance, 7.5% acrylamide gels are recommended for analyzing large proteins like LRRK1 and LRRK2, while 12.5% gels provide better resolution for smaller proteins such as Rab GTPases [6]. The bis-acrylamide to acrylamide crosslinking ratio is typically maintained at approximately 1:35 to create the three-dimensional network that forms the molecular sieve [3].

Critical Buffer Components and Recipes

The discontinuous buffer system developed by Laemmli is essential for achieving sharp protein bands during SDS-PAGE. The following table outlines key buffer compositions and their functions:

Table 2: Essential Buffer Systems and Components in SDS-PAGE [7] [5] [8]

| Buffer/Component | Composition | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer | 4% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 0.125 M Tris HCl, pH 6.8 | Denatures proteins, provides density for loading, visual tracking |

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40 or Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0 | Efficiently extracts proteins from cells and tissues |

| Stacking Gel | ~4% acrylamide, Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | Concentrates proteins into sharp bands before separation |

| Separating Gel | 8-15% acrylamide, Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | Separates proteins based on molecular weight |

| Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine-SDS, pH 8.3 | Conducts current and maintains SDS coating on proteins |

The pH transition between stacking gel (pH 6.8) and separating gel (pH 8.8) is crucial for the discontinuous buffer system to function properly [4]. At pH 6.8, glycine molecules in the running buffer exist predominantly in zwitterionic form with minimal net charge, migrating slowly until they reach the higher pH of the separating gel where they become fully negatively charged and migrate faster, leaving the proteins to separate by size [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting [7] [6] [9]

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents/Lysis Buffers | RIPA, NP-40, Tris-HCl, Triton X-100 | Solubilize and extract proteins from cellular or tissue samples |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-mercaptoethanol (BME) | Break disulfide bonds to completely linearize proteins |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF (1 mM), Aprotinin (2 µg/mL), Leupeptin (1-10 µg/mL) | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Sodium fluoride (5-10 mM), Orthovanadate (1 mM) | Preserve phosphorylation states for phospho-protein analysis |

| Gel Polymerization Agents | Ammonium persulfate (APS), TEMED | Catalyze acrylamide polymerization to form the gel matrix |

| Protein Assays | BCA, Bradford | Quantify protein concentration for equal loading across gels |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Prestained protein ladders (10-180 kDa, 10-250 kDa) | Provide reference for estimating protein molecular weights |

Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation

Sample Lysis and Protein Extraction

Proper sample preparation begins with efficient cell lysis and protein extraction. For adherent cells cultured in a 100mm dish, aspirate the culture medium and wash cells with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [7] [9]. Add 1 mL of appropriate ice-cold lysis buffer (such as RIPA buffer for total protein extraction) containing freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors [7] [5]. Scrape adherent cells using a cell scraper and transfer the suspension to a microcentrifuge tube. For suspension cells, pellet by centrifugation at 2,500 × g for 10 minutes, wash with PBS, and resuspend the pellet in lysis buffer [7]. Incubate the cell suspension on ice for 10-30 minutes with occasional agitation to ensure complete lysis [9] [5]. Clarify the lysate by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C and transfer the supernatant to a new tube [7].

Protein Quantification and Denaturation

Determine protein concentration using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay or Bradford assay according to manufacturer protocols [7] [9]. The BCA assay is particularly advantageous as it is compatible with samples containing up to 5% detergents and demonstrates less protein-to-protein variation compared to Bradford assays [7]. Normalize samples to the lowest protein concentration by adding additional lysis buffer. For denaturation, mix normalized lysate with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli sample buffer [5]. For reduced conditions, include DTT or β-mercaptoethanol at final concentrations of 50-100 mM [3] [5]. Heat samples at 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes to complete denaturation [7] [9]. Avoid heating at 100°C for extended periods as this may promote proteolysis [7]. Load 10-50 μg of total protein per lane for optimal separation and detection [9] [8].

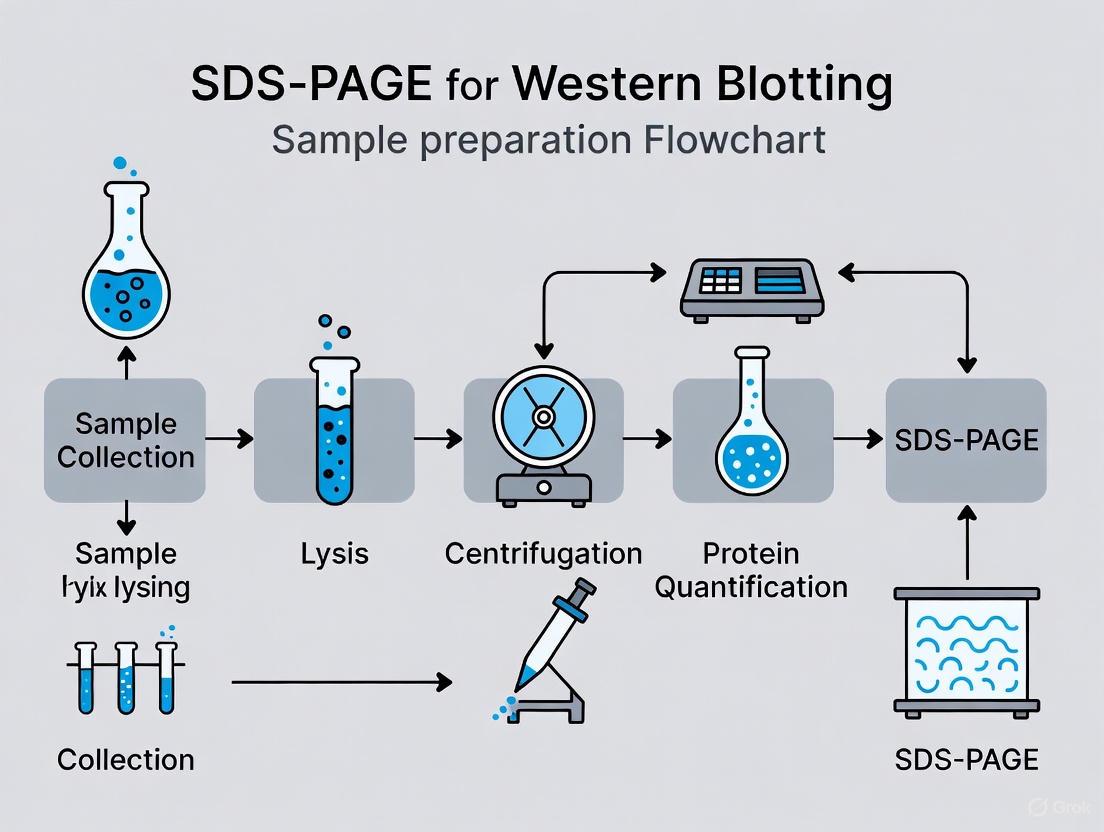

Diagram 2: Complete workflow for SDS-PAGE sample preparation, highlighting critical steps that ensure protein integrity and quantification accuracy.

Troubleshooting Common SDS-PAGE Issues

Protein Degradation and Poor Resolution

Protein degradation during sample preparation manifests as smeared bands across the gel. To prevent degradation, always prepare samples on ice or at 4°C and add fresh protease and phosphatase inhibitors to lysis buffers immediately before use [7] [5]. Aprotinin (targeting trypsin, chymotrypsin, and plasmin) should be used at 2 µg/mL, leupeptin (targeting lysosomal proteases) at 1-10 µg/mL, and PMSF (targeting serine proteases) at 1 mM concentration [5]. Incomplete denaturation appears as multiple bands for a single protein or vertical smearing. Ensure samples are properly heated (70-95°C for 5-10 minutes) in Laemmli buffer containing adequate SDS and reducing agents [7] [5]. Overheating samples (e.g., extended periods at 100°C) can promote proteolysis and should be avoided [7].

Irregular Band Patterns and Migration Artifacts

Uneven or distorted protein bands often result from improper sample loading or gel polymerization issues. To avoid distorted bands, be careful not to touch the bottom of wells with pipette tips during sample loading [9] [8]. Ensure complete polymerization of both stacking and resolving gels by allowing 30-60 minutes for polymerization at room temperature [6]. Poor stacking of proteins with insufficient concentration at the stacking-resolving gel interface can be addressed by verifying the pH of both stacking (pH 6.8) and resolving (pH 8.8) gels [4]. The discontinuous buffer system relies on the differential mobility of chloride and glycine ions at different pH levels to concentrate proteins into sharp bands before they enter the resolving gel [4].

The fundamental principle of SDS imparting uniform charge and denaturing proteins forms the cornerstone of reliable SDS-PAGE and western blotting. Through its dual mechanism of charge masking and protein linearization, SDS enables true molecular weight-based separation that is critical for accurate protein analysis. The experimental protocols outlined, when followed with attention to critical parameters such as buffer composition, protein quantification, and complete denaturation, ensure reproducible and interpretable results. Understanding these core principles allows researchers to effectively troubleshoot experimental challenges and optimize conditions for specific protein targets, ultimately enhancing the reliability of western blotting data in biomedical research and drug development.

Within the framework of investigating western blotting sample preparation, the polyacrylamide gel matrix stands as the fundamental component that enables the precise size-based separation of proteins. This application note details the core principles and methodologies of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), a technique that leverages this matrix to separate denatured proteins exclusively by their molecular weight [10] [11]. The reliability of SDS-PAGE makes it an indispensable first step in western blotting, forming the basis for accurate protein detection and analysis in research and drug development [12].

The principle of SDS-PAGE relies on a two-step process. First, proteins are denatured and uniformly coated with the negatively charged SDS detergent, which masks the proteins' intrinsic charges and confers a uniform charge-to-mass ratio [10] [13]. Second, these SDS-bound proteins are electrophoretically driven through a cross-linked polyacrylamide gel. This gel acts as a molecular sieve, where smaller proteins navigate the porous network more easily and migrate faster, while larger proteins are hindered and migrate more slowly [11]. This process results in the separation of a complex protein mixture into discrete bands based on molecular size [10].

Table 1: Key Reagents for SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation and Their Functions

| Reagent Category | Example Reagents | Function in Sample Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA Buffer, NP-40 Buffer, T-PER [12] [7] | Solubilizes proteins from cells or tissues; choice depends on protein subcellular location and need for denaturing conditions [12]. |

| Detergent | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [10] | Denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, negating the influence of native protein charge on migration [10] [13]. |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-Mercaptoethanol [10] [7] | Breaks disulfide bonds in proteins to fully unfold the polypeptide chains for accurate size-based separation [10]. |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitors | PMSF, Aprotinin, Sodium Fluoride, Sodium Orthovanadate [12] [7] | Added to lysis buffers to prevent protein degradation and dephosphorylation by endogenous enzymes released during cell disruption [12]. |

| Sample Buffer | Laemmli Buffer [12] [10] | Contains SDS, reducing agent, glycerol to density-load samples, and a tracking dye (e.g., bromophenol blue) to monitor electrophoresis progress [12]. |

Theoretical Foundation of the Molecular Sieve

The Polyacrylamide Gel Matrix

The polyacrylamide gel is created through the co-polymerization of acrylamide monomers and a cross-linking agent, most commonly methylenebisacrylamide [10]. The porosity of the resulting gel network, and thus its sieving properties, is determined by the concentration of acrylamide. A higher percentage of acrylamide creates a denser matrix with smaller pores, which is more effective at separating smaller proteins. Conversely, a lower percentage gel has larger pores and is better suited for resolving larger proteins [10] [13].

The standard SDS-PAGE setup employs a discontinuous gel system, which incorporates two distinct gel layers stacked vertically: a stacking gel and a separating gel (also called the resolving gel) [10]. The stacking gel, with a lower acrylamide concentration (typically 4-5%) and neutral pH, serves to concentrate all protein samples into a sharp, unified band before they enter the separating gel. The separating gel, with a higher acrylamide concentration (typically 8-15%) and basic pH (pH ~8.8), is where the actual size-based separation of proteins occurs [10]. This discontinuous system is critical for achieving high-resolution bands.

The Role of SDS in Protein Denaturation and Charge Uniformity

The key to separating proteins purely by size lies in the action of Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS). This anionic detergent binds to the hydrophobic regions of proteins in a constant ratio, approximately 1.4 g of SDS per 1.0 g of protein [10]. This extensive SDS coating accomplishes two critical goals: it disrupts nearly all the secondary and tertiary structure of the protein, linearizing the polypeptide chain, and it imparts a large, uniform negative charge that overwhelms the protein's inherent charge [10] [13]. Consequently, when an electric field is applied, all SDS-bound proteins migrate towards the anode with a mobility dependent solely on their molecular size, as the charge-to-mass ratio is nearly identical for all species [11].

Diagram 1: Protein denaturation and SDS-binding workflow. This process ensures proteins are linearized and uniformly charged, allowing separation by molecular weight alone.

Experimental Protocol for SDS-PAGE

Sample Preparation for Western Blotting

Proper sample preparation is the most critical factor for a successful western blot, as it directly impacts the quality of separation on the polyacrylamide gel [14] [7]. The overarching goal is to extract, denature, and reduce proteins without degradation or modification.

Cell Culture Lysate Preparation (Adherent Cells) [7]:

- Lysis: Place the cell culture dish on ice, wash cells with ice-cold PBS, and aspirate. Add ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (~1 mL per 10â· cells). Gently shake on ice for 5 minutes [7].

- Clarification: Scrape the lysate and transfer it to a microcentrifuge tube. Centrifuge at ~14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris [7].

- Protein Quantification: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube. Determine protein concentration using a compatible assay, such as the BCA assay, which is tolerant of many detergents and denaturing agents found in lysis buffers [12] [7].

- Sample Denaturation: Dilute the protein lysate with an appropriate volume of sample buffer (e.g., 2X Laemmli buffer) containing SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., DTT). A common final volume is 10-20 µL. Heat the samples at 70°C for 10 minutes (or 95°C for 5 minutes) to fully denature the proteins [10] [7].

Tissue Lysate Preparation [7]:

- Homogenization: Dissect the tissue of interest and weigh it. Add ice-cold lysis buffer (e.g., T-PER or RIPA) at a ratio of ~50 mg tissue to 1,000 µL of buffer. Homogenize the tissue thoroughly on ice using a Dounce homogenizer, sonicator, or mechanical homogenizer [14] [7].

- Clarification and Quantification: Centrifuge the homogenate at 10,000 x g for 5 minutes to pellet debris. Transfer the supernatant and determine protein concentration as described for cell lysates [7].

Table 2: Lysis Buffer Selection Guide Based on Protein Localization [12] [7]

| Target Protein Location | Recommended Buffer Type | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Cell (Mild Lysis) | NP-40 or Triton X-100 Buffer | Non-denaturing detergents that preserve protein-protein interactions and native epitopes [12]. |

| Whole Cell (Strong Lysis) | RIPA Buffer | Contains ionic detergents (SDS, deoxycholate) effective for membrane-bound, nuclear, and mitochondrial proteins [12] [7]. |

| Cytoplasmic | Tris-HCl or NP-40-based Buffer | Mild buffers designed to lyse the plasma membrane while leaving nuclei intact [12]. |

| Membrane-Bound Proteins | RIPA Buffer | The combination of detergents helps solubilize hydrophobic membrane proteins [12]. |

| Nuclear | RIPA Buffer | Effective at disrupting the nuclear envelope; sample may require sonication or nuclease treatment to reduce viscosity from DNA [12]. |

Gel Electrophoresis and Protein Separation

The prepared samples are then loaded into the wells of the polyacrylamide gel for separation.

Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis [10]:

- Assemble the Gel Cast: Secure clean glass plates with spacers in a casting stand. The protocol below is for a discontinuous Tris-Glycine gel.

- Prepare and Cast the Separating Gel: Mix components for the separating gel (e.g., 1.5 M Tris-HCl pH 8.8, acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, 10% SDS, APS, and TEMED). Pour the solution between the glass plates, leaving space for the stacking gel. Overlay with a water-saturated alcohol (e.g., isopropanol) to create a flat interface. Allow the gel to polymerize completely [10].

- Prepare and Cast the Stacking Gel: After discarding the alcohol overlay, prepare the stacking gel solution (e.g., 0.5 M Tris-HCl pH 6.8, a lower percentage of acrylamide, SDS, APS, and TEMED). Pour it on top of the polymerized separating gel and immediately insert a sample comb. Allow to polymerize [10].

- Load Samples and Run Electrophoresis: Once set, remove the comb and place the gel into the electrophoresis chamber filled with running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine-SDS). Load equal amounts of total protein (e.g., 10-40 µg) from your prepared samples and a molecular weight marker (protein ladder) into the wells. Apply a constant voltage (e.g., 80-150 V) until the dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel [10] [7].

Diagram 2: SDS-PAGE workflow showing sample stacking and separation. Proteins are first focused into a sharp band in the stacking gel before being separated by size in the resolving gel.

Applications in Protein Analysis and Quality Control

The primary application of SDS-PAGE in the context of western blotting sample preparation is to separate proteins by molecular weight prior to transfer to a membrane. However, its utility extends far beyond this single step.

- Protein Purity and Integrity Assessment: SDS-PAGE is routinely used to analyze the purity of protein samples during purification and to check for protein degradation, which is visible as smearing or unexpected lower molecular weight bands on the gel [13].

- Molecular Weight Estimation: By comparing the migration distance of an unknown protein to that of standard proteins in a molecular weight marker, researchers can estimate the apparent molecular weight of the protein of interest [10].

- Analysis of Protein Complexes: Comparing samples run under reducing (with DTT/β-ME) and non-reducing (without reducing agent) conditions allows researchers to infer the presence of disulfide-bonded subunits within a protein complex [10] [13].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Common SDS-PAGE Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smearing Bands | Protein degradation; Overloaded sample. | Keep samples on ice; use fresh protease inhibitors. Load less protein [12] [7]. |

| Atypical Band Migration | Improper sample denaturation; Incomplete reduction. | Ensure samples are heated adequately (70-95°C). Use fresh reducing agent (DTT/β-ME) [10]. |

| Poor Resolution | Incorrect acrylamide percentage; Air bubbles in gel. | Choose gel % appropriate for target protein size. Pour gels carefully to avoid bubbles [10]. |

| No Bands | Insensitive staining; Low protein abundance. | Use more sensitive stain (e.g., silver stain) or load more protein. For western blotting, optimize antibody detection [10]. |

| Wavy Bands | Excess salt in sample; Uneven cooling. | Desalt samples or use sample clean-up. Ensure even heat dissipation during run [12]. |

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a cornerstone technique for protein separation based on molecular weight, and its efficacy in western blotting sample preparation hinges on a discontinuous buffer system utilizing two distinct gel layers [15] [16]. This system is ingeniously designed to overcome the key challenge of achieving high-resolution separation: if protein samples entered the resolving gel spread out over their entire loading volume, the result would be a smeared, uninterpretable band [15]. The discontinuous system solves this by leveraging differences in gel composition, pH, and buffer chemistry to concentrate the protein samples into a sharp, unified line before they begin the actual separation, thereby ensuring the sharply defined bands critical for accurate analysis in research and drug development [15] [17].

The foundation of this process is the detergent SDS, which plays two critical roles. First, it unfolds proteins by disrupting non-covalent bonds, causing them to lose their higher-order structures and become linear polypeptides [15] [16]. Second, SDS binds to the proteins with high affinity, effectively coating them with a uniform negative charge [15] [16]. This negates the proteins' intrinsic electrical charges, ensuring that their migration through the gel is determined solely by molecular weight, not by charge [16].

The Distinct Roles of Stacking and Resolving Gels

The discontinuous gel system comprises two layers with unique chemical and physical properties that work in concert. The table below summarizes the core differences between these two layers.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Stacking and Resolving Gels

| Parameter | Stacking Gel | Resolving Gel |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | To concentrate and align all protein samples into a sharp band before they enter the resolving gel [15] [17] | To separate the focused proteins based on their molecular weight [15] [17] |

| Typical Acrylamide Percentage | Low (around 4-5%) [17] [16] | Higher (ranging from 8% to 20%, depending on target protein size) [18] [19] |

| pH Environment | Lower pH (6.8) [15] [17] | Higher pH (8.8) [15] [17] |

| Pore Size | Larger pores for freer protein movement [15] | Smaller pores, creating a molecular sieve that retards larger proteins more than smaller ones [15] [16] |

The Crucial Role of Glycine and the Stacking Mechanism

The mechanism of stacking is driven by the unique chemistry of glycine, an amino acid in the running buffer, and its interaction with the different pH environments of the two gels [15].

In the running buffer (pH 8.3), glycine exists predominantly as a negatively charged glycinate anion [15]. When the electric current is applied, these anions enter the stacking gel (pH 6.8). At this lower pH, a significant proportion of glycine molecules become zwitterions—neutral molecules with both positive and negative charges [15]. As a result, their electrophoretic mobility drops dramatically.

This sets up a critical dynamic with the highly mobile chloride ions (Clâ») from the Tris-HCl in the stacking gel. The chloride ions race ahead as a "leading ion" front, while the slow-moving glycine zwitterions form a "trailing ion" front [15]. The protein-SDS complexes, whose electrophoretic mobility is intermediate, are squeezed into a narrow, sharply defined zone between these two fronts. This process effectively "stacks" all proteins into a thin line, which is then ushered into the resolving gel [15].

Upon reaching the resolving gel (pH 8.8), the glycine zwitterions are rapidly deprotonated, regaining their negative charge and high mobility as glycinate anions. These anions then speed past the protein layer, depositing the now-concentrated proteins as a tight band at the top of the resolving gel, where the actual separation based on size begins [15].

Diagram: Ion Dynamics in Discontinuous SDS-PAGE

Experimental Protocol for Gel Casting and Electrophoresis

Reagent Preparation

The following table lists the essential reagents and their functions for preparing discontinuous SDS-PAGE gels.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Reagent / Component | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide (30%) | Forms the polyacrylamide polymer matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [18] [16]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Provides the buffering environment at specific pH levels (1.5 M, pH 8.8 for resolving gel; 0.5 M, pH 6.8 for stacking gel) [15] [18]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge [15] [16]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | Initiator of the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide [18] [16]. |

| TEMED | Catalyst that acts with APS to accelerate acrylamide polymerization [18] [16]. |

| Glycine | Key amino acid in running buffer whose charge-state changes drive the stacking mechanism [15]. |

| Isopropanol | Layered on unpolymerized resolving gel to create a flat, oxygen-free interface [16]. |

Step-by-Step Gel Casting and Running Protocol

Part A: Casting the Discontinuous Gel This protocol is adapted for casting a standard 1.0 mm thick mini-gel system [18].

- Assemble Gel Cassette: Clean and assemble glass plates and spacers in the casting stand [16].

- Prepare Resolving Gel: Mix components for the resolving gel (see Table 3 for volumes). Add 10% APS and TEMED last, as they immediately initiate polymerization. Mix gently [18] [16].

- Pour Resolving Gel: Using a pipette, immediately transfer the resolving gel solution into the cassette. Leave space for the stacking gel (approx. 2.5 cm from the top) [18].

- Layer with Isopropanol: Carefully overlay the resolving gel with isopropanol to exclude air and ensure a flat surface [16]. Allow 30-45 minutes for complete polymerization [18].

- Prepare and Pour Stacking Gel: After polymerization, pour off the isopropanol and rinse with water. Mix the stacking gel components (Table 3), add APS and TEMED, and pour directly onto the polymerized resolving gel [18] [16].

- Insert Comb: Immediately insert a clean comb into the stacking gel, avoiding bubbles. Allow 20-30 minutes to polymerize fully [18].

Table 3: SDS-PAGE Gel Recipe for a 10% Resolving Gel (Volumes for 2 gels)

| Component | Resolving Gel (10%) | Stacking Gel (4-5%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O | 4.0 mL | 3.78 mL |

| 30% Acrylamide Mix | 3.3 mL | 0.99 mL |

| 1.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.8) | 2.5 mL | - |

| 0.5 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) | - | 1.9 mL |

| 10% SDS | 100 µL | 75 µL |

| 10% APS | 50 µL | 37.5 µL |

| TEMED | 5 µL | 7.5 µL |

| Total Volume | ~10 mL | ~6.75 mL |

Part B: Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis

- Prepare Protein Samples: Mix protein lysate with Laemmli buffer (containing SDS, reducing agents like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol, glycerol, and tracking dye) [15] [12]. Heat samples at 95°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [16].

- Load Gel: Place the polymerized gel into the electrophoresis chamber and fill with running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [19]. Carefully load equal amounts of protein (20-50 µg for cell lysates) and a molecular weight marker into the wells [19].

- Run Electrophoresis: Connect the power supply (cathode at the top, anode at the bottom) and run at a constant voltage. A standard setting is 100-150 V until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel (approx. 1-2 hours) [19]. Bubbles will form at the electrodes due to the electrolysis of water, confirming the circuit is complete [15].

- Downstream Processing: Following electrophoresis, the gel can be stained for direct protein visualization or used for western blotting, where proteins are transferred to a membrane for antibody-based detection [12] [20].

Optimization and Technical Considerations

Choosing the Correct Acrylamide Percentage

The resolution of proteins is critically dependent on the acrylamide percentage of the resolving gel. The appropriate percentage should be selected based on the molecular weight of the target protein(s) to achieve optimal separation [18] [19].

Table 4: Gel Percentage Selection Guide Based on Protein Size

| Target Protein Size (kDa) | Recommended Gel Percentage |

|---|---|

| 4 - 40 | 15 - 20% [18] [19] |

| 12 - 45 | 15% [18] [19] |

| 10 - 70 | 12.5% [18] [19] |

| 15 - 100 | 10% [18] [19] |

| 25 - 200 | 8% [18] |

| > 200 | 4 - 6% [19] |

For samples containing proteins of widely varying sizes, gradient gels (e.g., 4-20% acrylamide) are recommended as they provide a broad separation range and sharper bands across the entire gel [19].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Smearing or Poor Resolution: This can result from incomplete denaturation of proteins. Ensure samples are heated sufficiently with SDS and reducing agents [16]. Overloading protein can also cause smearing.

- Atypical Migration: If a protein runs at a molecular weight different from expected, consider post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) which can alter SDS binding and mobility [15].

- Wavy Bands: This is often due to excess heat during the run. Running the gel at a lower voltage or in a cold room can improve band straightness [12].

The discontinuous SDS-PAGE system, with its strategic use of stacking and resolving gels, remains an indispensable tool for protein analysis. A deep understanding of the underlying principles—the pH-induced changes in glycine charge and the creation of a mobility gradient—enables researchers to reliably produce the sharp, well-separated protein bands essential for accurate western blotting. Proper execution of the gel casting protocol, combined with informed optimization of parameters like acrylamide percentage, ensures robust and reproducible results, forming a critical foundation for successful research and diagnostic applications.

Within the framework of advanced research on SDS-PAGE for western blotting sample preparation, a meticulous understanding of the core chemical components is paramount for success. This application note provides an in-depth analysis of the three fundamental reagent classes—SDS, reducing agents, and buffer systems—that govern protein denaturation, stability, and electrophoretic mobility. For researchers and drug development professionals, optimizing these components is not a mere preliminary step but a critical process that directly impacts the resolution, specificity, and reproducibility of protein analysis, thereby influencing downstream conclusions in biomarker discovery and therapeutic development.

The Core Chemical Trio: Functions and Mechanisms

The integrity of an SDS-PAGE experiment hinges on the synergistic action of SDS, reducing agents, and buffering systems. Each component addresses a specific challenge in preparing a complex protein mixture for size-based separation.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS): The Denaturing Charge Conferrer

SDS is a strong anionic detergent that serves two primary, interdependent functions in sample preparation [21]. First, it binds to the hydrophobic regions of proteins, disrupting hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces. This action effectively unfolds or denatures proteins, dismantling their secondary and tertiary structures to produce linear polypeptide chains [22]. Second, SDS coats the protein backbone at a relatively constant ratio of about 1.4 g SDS per 1.0 g protein [21]. Given its negatively charged sulfate head group, this uniform coating imparts a uniform negative charge to all proteins [22]. Consequently, the intrinsic charge of a protein is masked, and all proteins gain a similar charge-to-mass ratio. This allows separation by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to proceed primarily on the basis of molecular weight rather than native charge or shape [23] [22].

Reducing Agents: The Disulfide Bond Disruptors

While SDS unfolds most of a protein's structure, it cannot break covalent disulfide bonds that stabilize tertiary and quaternary structures. Reducing agents, such as β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) or Dithiothreitol (DTT), are incorporated into the sample buffer for this purpose [24]. These compounds reduce disulfide bridges between cysteine residues, converting cystine into two cysteine molecules [24]. This action ensures that multimeric protein complexes are dissociated into individual subunits and that all proteins are converted to their fully linear, monomeric forms. This is a prerequisite for accurate molecular weight determination, as a protein's migration distance will otherwise reflect its oligomeric state rather than the mass of its polypeptide chain(s).

Buffer Systems: The pH and Environment Regulators

Buffers are essential for maintaining a stable pH throughout the sample preparation and electrophoresis process, which is critical for controlling protein charge and migration. The sample buffer, typically Laemmli buffer, contains Tris-HCl to maintain a stable pH during denaturation [24]. The entire system operates within a specific pH range to ensure that SDS remains negatively charged and proteins are fully denatured. The correct ionic strength, provided by components like NaCl, is also vital for minimizing protein aggregation and unwanted ionic interactions [25].

Table 1: Key Components of SDS-PAGE Sample Buffer and Their Functions

| Component | Primary Function | Mechanism of Action | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Denature proteins and impart negative charge [21] [22] | Binds protein backbone, masking intrinsic charge; unfolds 2° and 3° structure [24] | Binding can vary slightly with hydrophobicity or PTMs (e.g., glycosylation) [21] |

| Reducing Agent (e.g., DTT, β-ME) | Reduce disulfide bonds [24] | Breaks S-S bonds, dissociating multimers and linearizing subunits [24] | Essential for accurate MW determination of disulfide-linked proteins; can be omitted for "non-reduced" analysis |

| Glycerol | Increase sample density [21] [24] | Allows sample to sink to bottom of gel well during loading [24] | Prevents sample diffusion and ensures even loading across wells |

| Tracking Dye (e.g., Bromophenol Blue) | Visualize migration [21] [24] | Provides a visible front to monitor electrophoresis progress [24] | Small size migrates faster than proteins, signaling when to stop run |

Experimental Protocol for Sample Preparation

The following detailed protocol is designed for the preparation of protein lysates from mammalian cell culture, a common starting point for western blotting in research and drug development pipelines.

Reagent Preparation

- Lysis Buffer Selection: Choose an appropriate lysis buffer based on the subcellular localization of your target protein [7] [24]. RIPA buffer is suitable for membrane-bound, nuclear, or mitochondrial proteins, while NP-40 Lysis Buffer is milder and recommended for whole-cell or cytoplasmic extracts [7] [24].

- Inhibitor Cocktail: Freshly add protease and phosphatase inhibitors to the lysis buffer to prevent protein degradation and post-translational modification loss [7] [24]. A typical cocktail includes PMSF (1 mM for serine proteases), EDTA (1-5 mM for metalloproteases), Sodium Fluoride (5-10 mM), and Orthovanadate (1 mM) [24].

- 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer: Prepare a standard 2X reducing sample buffer containing 4% SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.125 M Tris HCl (pH 6.8), 0.004% Bromophenol Blue, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol or 100 mM DTT [24].

Cell Lysis and Protein Extraction

- Wash and Aspirate: For adherent cells, place the culture dish on ice, carefully aspirate the media, and wash the cell monolayer with ice-cold Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) [7] [24].

- Add Lysis Buffer: Aspirate the PBS and add ice-cold lysis buffer (~1 mL per 10â· cells or a 100 mm plate) [7].

- Scrape and Recover: Using a cell scraper, dislodge the cells from the plate and transfer the suspension to a pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube.

- Incubate and Centrifuge: Agitate the lysate gently for 30 minutes at 4°C to complete lysis. Centrifuge at approximately 14,000 x g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble debris [7] [8].

- Collect Supernatant: Transfer the clarified supernatant (the protein lysate) to a new tube placed on ice. Discard the pellet.

Protein Quantification and Sample Denaturation

- Determine Concentration: Quantify the protein concentration of the lysate using a compatible protein assay, such as the BCA assay or Bradford assay [7] [8]. The BCA assay is particularly advantageous as it is compatible with samples containing up to 5% detergents and shows less protein-to-protein variability [7].

- Dilute and Mix: Dilute the lysate to the desired concentration and mix an equal volume of lysate with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer [24]. A typical total protein load is 10-50 μg per lane [8] [24].

- Denature and Reduce: Heat the mixture at 95-100°C for 5 minutes in a heat block or water bath to fully denature and reduce the proteins [8] [24].

- Brief Spin: Centrifuge the denatured samples at high speed for 1 minute to collect any condensation before loading onto the gel [23].

The Discontinuous Buffer System in SDS-PAGE

The standard SDS-PAGE setup employs a sophisticated discontinuous buffer system that utilizes different pH values and gel densities to concentrate proteins into a sharp stack before they enter the resolving gel, leading to superior band resolution [21].

Diagram 1: Discontinuous SDS-PAGE Buffer Mechanism

In the stacking gel (pH ~6.8), glycine from the running buffer exists primarily as a zwitterion with minimal net charge, causing it to migrate slowly [21]. Chloride ions (Clâ») from the Tris-HCl in the gel are highly mobile. This creates a steep voltage gradient between the fast Clâ» front (leading ion) and the slow glycine front (trailing ion). Proteins, with their intermediate mobility, are compressed into a razor-thin zone between these two fronts [21]. Upon reaching the resolving gel (pH ~8.8), glycine gains a strong negative charge and ionizes into glycinate anions, allowing it to migrate rapidly [21]. The proteins, now deposited at the top of the dense resolving gel and no longer compressed, begin to separate based solely on their molecular weight as they are sieved through the polyacrylamide matrix.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guide

Even with a sound understanding of the principles, optimization is often required for challenging protein targets.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Sample Preparation Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared Bands | Incomplete denaturation or reduction; high salt concentration [25] | Add fresh reducing agent; ensure boiling for 5 min at 95-100°C; reduce salt concentration to <500 mM [25] |

| Multiple/Unexpected Bands | Protein degradation, oxidation, or dephosphorylation [25] | Use fresh protease/phosphatase inhibitors; include fresh reducing agents in buffer [25] |

| Weak or No Signal | Over- or under-loading of protein; incomplete transfer | Quantify protein concentration accurately before loading (e.g., BCA assay) [7] [25] |

| Protein Running at Incorrect MW | Post-translational modifications (e.g., glycosylation, phosphorylation) affecting SDS binding [21] | Consider if PTMs are expected; use bioinformatics tools to predict protein behavior [25] |

Advanced Optimization Strategies

- Gel Percentage Selection: The optimal acrylamide concentration depends on the molecular weight of your target protein. Use lower percentages (e.g., 8-10%) for high molecular weight proteins (>100 kDa) and higher percentages (e.g., 12-15%) for low molecular weight proteins (<50 kDa) [25] [8]. Gradient gels (e.g., 4-20%) can resolve a broad size range simultaneously.

- Alternative Conditions: Some antibodies recognize conformational epitopes that are destroyed by denaturation. For such targets, native PAGE (omitting SDS and reducing agents) or non-reducing SDS-PAGE (omitting the reducing agent only) may be necessary [7] [24].

- Heating Temperature: While 95-100°C is standard, excessive heat can promote protein aggregation or proteolysis for some sensitive proteins. A lower denaturation temperature of 70°C for 10 minutes can be a effective alternative [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful western blot begins with high-quality, specific reagents. The following toolkit is essential for the sample preparation workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE Sample Preparation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA Buffer, NP-40 Lysis Buffer, T-PER [7] [8] [24] | Solubilize proteins from cells/tissues; choice depends on protein localization and solubility [7] [24] |

| Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitors | PMSF, Aprotinin, Leupeptin, Sodium Fluoride, Sodium Orthovanadate [7] [24] | Preserve protein integrity and phosphorylation states by inhibiting endogenous enzymes [7] [24] |

| Sample (Loading) Buffer | Laemmli Buffer (2X, 4X, 6X), Reducing or Non-Reducing formulations [8] [24] | Denature, reduce, and color-tag proteins for electrophoresis; density agent ensures proper gel loading [21] [24] |

| Reducing Agents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), β-Mercaptoethanol (β-ME), Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) [24] | Linearize proteins by breaking disulfide bonds for accurate molecular weight analysis [24] |

| Protein Assay Kits | BCA Assay, Bradford Assay [7] [8] | Accurately determine protein concentration for equal loading across gel lanes, essential for quantification [7] [25] |

Choosing the Right Gel Percentage for Your Target Protein Size

Within the framework of optimizing western blotting sample preparation, the selection of an appropriate polyacrylamide gel concentration for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is a critical foundational step. SDS-PAGE separates proteins based solely on their molecular weight, a process enabled by the denaturing action of SDS, which confers a uniform negative charge and linearizes the proteins [26]. The polyacrylamide gel acts as a molecular sieve, where the pore size, determined by the gel percentage, dictates the resolution of proteins within specific molecular weight ranges [27]. Selecting an incorrect gel percentage is a prevalent source of poor band separation, leading to inaccurate molecular weight determination and compromised detection in subsequent western blotting. This guide provides detailed protocols and data to enable researchers and drug development professionals to make informed decisions for optimal protein separation.

The Principle of Protein Separation by SDS-PAGE

The core principle of SDS-PAGE is the separation of denatured proteins according to their molecular weight as they migrate through a polyacrylamide gel matrix under an electric field [26]. The anionic detergent SDS plays a dual role: it denatures proteins by breaking non-covalent interactions, unfolding them into linear chains, and it coats the polypeptides with a uniform negative charge [26]. This process negates the influence of a protein's inherent charge or complex three-dimensional structure, ensuring that migration is dependent primarily on size [27].

The polyacrylamide gel, formed through the polymerization of acrylamide and a cross-linker, creates a porous mesh. The size of these pores is inversely related to the percentage of acrylamide; a higher percentage gel creates a tighter mesh with smaller pores, while a lower percentage gel creates a more open matrix with larger pores [27]. Consequently, smaller proteins migrate more rapidly through the gel matrix, while larger proteins are impeded and migrate more slowly [26]. The following diagram illustrates the workflow and the logical relationship between protein size and gel percentage.

Gel Percentage Selection Guide

Choosing the correct acrylamide concentration is paramount for achieving high-resolution separation. As a general rule, low molecular weight proteins are best resolved on high-percentage gels, whereas large proteins require lower-percentage gels for sufficient resolution [28]. Using a gel with a pore size that is too small for a large protein will result in the protein being trapped near the top of the gel, while a small protein run on a low-percentage gel may migrate too quickly and poorly separate from other small proteins [27]. The tables below provide specific recommendations for single-concentration gels based on the molecular weight of your target protein.

Table 1: Recommended Gel Percentages for Protein Separation

| Protein Size (kDa) | Recommended Gel Percentage (%) | Protein Size (kDa) | Recommended Gel Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 - 40 | 20% [29] | 10 - 70 | 12.5% [28] |

| 12 - 45 | 15% [28] [29] | 15 - 100 | 10% [28] [29] |

| 25 - 200 | 7.5% [29] | 50 - 200 | 8% [28] |

| >200 | 4-6% [28] | >200 | 5% [29] |

For experiments targeting a single protein or proteins of similar size, a single-concentration gel is sufficient and recommended. However, when analyzing multiple proteins with significantly differing molecular weights, gradient gels are necessary [28] [29]. Gradient gels contain an increasing concentration of acrylamide from top to bottom, creating a pore size gradient that provides optimal separation for a very wide range of protein sizes on a single gel [28] [26]. The following decision chart provides a visual guide for selecting the appropriate gel type and percentage.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Casting a Single-Percentage Resolving Gel

This protocol details the preparation of a polyacrylamide resolving gel, adapted from general laboratory methods [29]. The recipe table below is formatted for a 10 mL gel, sufficient for a standard mini-gel format.

Table 2: Resolving Gel Recipes for Different Acrylamide Percentages

| Reagent | Order | 5% | 7.5% | 10% | 12% | 15% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dHâ‚‚O | 1 | 5.61 mL | 4.78 mL | 3.98 mL | 3.28 mL | 2.34 mL |

| 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 | 2 | 2.5 mL | 2.5 mL | 2.5 mL | 2.5 mL | 2.5 mL |

| 10% (w/v) SDS | 3 | 100 µL | 100 µL | 100 µL | 100 µL | 100 µL |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis (29.2:0.8) | 4 | 1.67 mL | 2.5 mL | 3.3 mL | 4.0 mL | 5.0 mL |

| 10% (w/v) Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 5 | 50 µL | 50 µL | 50 µL | 50 µL | 50 µL |

| TEMED | 6 | 5 µL | 5 µL | 5 µL | 5 µL | 5 µL |

Procedure:

- Clean and Assemble: Clean the glass plates and spacers thoroughly and assemble the gel cassette according to the manufacturer's instructions [29].

- Mix Resolving Gel: In a beaker or conical flask, combine dHâ‚‚O, Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), SDS, and Acrylamide/Bis solution in the volumes specified in Table 2 for your desired gel percentage. Caution: Acrylamide is a potent neurotoxin; wear gloves and appropriate personal protective equipment.

- Initiate Polymerization: Immediately before pouring, add 10% APS and TEMED. Swirl gently to mix. Do not vortex. TEMED catalyzes polymerization, so work quickly from this point.

- Pour the Gel: Using a pipette, immediately transfer the gel solution into the gap between the glass plates. Leave sufficient space for the stacking gel (comb height plus ~1 cm).

- Overlay: Carefully overlay the gel solution with water-saturated butan-1-ol or deionized water to expel air and create a flat, even interface.

- Polymerize: Allow the gel to polymerize completely for 15-60 minutes at room temperature. A distinct schlieren line will appear between the gel and the overlay once polymerization is complete.

Protocol: Preparing and Loading Samples for SDS-PAGE

Proper sample preparation is critical for clear and accurate results. Common issues like smearing, distortion, and poor resolution often originate at this stage [30] [31] [27].

Sample Preparation:

- Denature Protein: Mix the protein sample with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli sample buffer (containing SDS and a reducing agent like DTT or β-mercaptoethanol). The final concentration of reducing agent should be less than 50 mM for DTT or less than 2.5% for β-mercaptoethanol to prevent artifacts [30].

- Heat Denature: Heat the samples at 98°C for 5 minutes to fully denature the proteins [27]. Critical step: After heating, immediately place the samples on ice to prevent gradual cooling and protein renaturation [27].

- Brief Centrifuge: Centrifuge the samples briefly to collect condensation.

Gel Loading:

- Prepare Gel: Once the resolving gel has polymerized, pour off the overlay. Rinse the gel surface with deionized water and remove any residual liquid with a tissue wick.

- Pour Stacking Gel: Prepare and pour the stacking gel (see Table 3 for recipe), insert the comb, and allow it to polymerize for ~30 minutes [29].

- Load Samples: Install the gel in the electrophoresis apparatus and fill the tank with 1X running buffer (25 mM Tris base, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) [28].

- Rinse Wells: Before loading, rinse the wells with a small amount of running buffer to remove unpolymerized acrylamide and air bubbles, which can cause sample leakage and distorted bands [31].

- Load Carefully: Load 10-50 µg of cell lysate or 10-100 ng of purified protein per lane [28]. Do not overfill wells; a maximum of 3/4 of the well's capacity is a general rule [31]. Include a prestained protein ladder in one lane for molecular weight reference.

- Run Gel: Connect the power supply and run the gel at a constant voltage of 100-150 V for 40-60 minutes, or until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [26].

Table 3: Stacking Gel Recipe (5 mL)

| Reagent | Order | Volume |

|---|---|---|

| dHâ‚‚O | 1 | 3.05 mL |

| 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 | 2 | 1.25 mL |

| 10% (w/v) SDS | 3 | 50 µL |

| 30% Acrylamide/Bis (29.2:0.8) | 4 | 650 µL |

| 10% (w/v) APS | 5 | 25 µL |

| TEMED | 6 | 10 µL |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SDS-PAGE

| Item | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis Solution (30%) | Pre-mixed monomer and cross-linker for forming the polyacrylamide gel matrix. Handle with extreme care as it is a neurotoxin. [29] |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (1.5 M, pH 8.8) | Provides the appropriate alkaline pH for the resolving gel, crucial for the stacking and separation principles of discontinuous SDS-PAGE. [29] |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (0.5 M, pH 6.8) | Provides the lower pH environment required for the stacking gel to concentrate proteins before they enter the resolving gel. [29] |

| 10% SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent used to denature proteins and confer a uniform negative charge. Added to both gels and running buffer. [28] [26] |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalysts for the polymerization reaction of acrylamide. APS is the initiator, and TEMED is the accelerator. Must be fresh for efficient polymerization. [29] [27] |

| Protein Molecular Weight Marker | A set of proteins of known size run alongside samples to estimate the molecular weight of unknown proteins. Available prestained (to monitor run and transfer) or unstained (for accurate size determination). [28] [32] |

| Electrophoresis Running Buffer | Typically 1X Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS). Conducts current and maintains pH and SDS concentration during the run. Should be fresh for optimal results. [28] [27] |

| 2X Laemmli Sample Buffer | Contains SDS, glycerol (for density), a reducing agent (DTT/BME), and bromophenol blue (tracking dye). Prepares the protein sample for denaturing gel electrophoresis. [30] |

| Dcpib | Dcpib, CAS:82749-70-0, MF:C22H28Cl2O4, MW:427.4 g/mol |

| DC-S239 | DC-S239, MF:C15H15N3O5S, MW:349.4 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Poor band separation and distortion can stem from various issues in sample preparation, gel formulation, and electrophoresis conditions. The table below summarizes common problems and their solutions.

Table 5: Troubleshooting Poor Band Separation and Other Common Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Band Separation/ Smearing | Incorrect gel percentage for protein size [27]. | Refer to Table 1 and select an appropriate gel percentage. Use a gradient gel for wide size ranges [28]. |

| Incomplete protein denaturation [27]. | Ensure proper heating (5 min, 98°C) and immediate cooling on ice. Check SDS and reducing agent concentrations [27]. | |

| Too much protein loaded per lane [30] [27]. | Reduce the sample load. For mini-gels, a maximum of 0.5 µg per band or 10–15 µg of cell lysate per lane is recommended [30]. | |

| Vertical Smiling/ Frowning Bands | Gel running too hot (smiling) or uneven current [26]. | Run the gel at a lower voltage for a longer duration or use a cooling apparatus [27]. |

| Bands Not Straight/ Lane Widening | High salt concentration in sample (>100 mM) [30]. | Dialyze samples or use a concentrator to desalt and reduce salt concentration below 100 mM [30]. |

| DNA contamination [30]. | Shear genomic DNA by sonication or pass samples through a fine-gauge needle to reduce viscosity [30]. | |

| No Bands or Weak Bands | Insufficient protein transfer or low protein [30]. | Check transfer efficiency by staining the gel post-transfer. Increase the amount of protein loaded [30]. |

| Protein Aggregation in Well | Protein precipitation or aggregation [31]. | Ensure sample solubility by adequate homogenization. Add 4-8M urea for hydrophobic proteins. Add DTT/BME to lysis solution [31]. |

| Sample Leaking from Well | Air bubbles in well or overfilling [31]. | Rinse wells with running buffer before loading. Do not load a well more than 3/4 of its capacity [31]. |

| Insufficient glycerol in loading buffer [31]. | Check that the sample buffer contains enough glycerol (or sucrose) to make the sample denser than the running buffer. |

Proven SDS-PAGE Protocol: From Sample Prep to Electrophoresis

Optimal Protein Extraction and Quantification Methods (Bradford, BCA)

Within the framework of SDS-PAGE and western blotting research, the accuracy of experimental results is fundamentally dependent on two critical upstream processes: effective protein extraction and precise protein quantification. Protein extraction involves the liberation of proteins from their biological matrix (cells or tissues) into a soluble form, while maintaining their integrity and preventing degradation [7]. Protein quantification is the subsequent precise measurement of protein concentration, which is essential for loading equal amounts of protein across gel lanes, thereby ensuring valid comparisons and reliable downstream analysis [33]. The failure to optimize these initial steps can introduce significant variability, compromise detection sensitivity, and lead to erroneous interpretations in western blotting.

The Bradford and Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) assays represent two of the most prevalent colorimetric methods for determining protein concentration. Despite sharing a common purpose, their underlying chemical principles differ substantially, informing their specific applications and limitations. The Bradford assay operates on a single-step mechanism where the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye binds primarily to basic amino acids (arginine, lysine) in proteins under acidic conditions [34] [35]. This binding induces a shift in the dye's absorbance maximum from 465 nm (reddish-brown) to 595 nm (blue), with the intensity of the blue color being proportional to the protein concentration [35].

In contrast, the BCA assay is a two-step process that occurs under alkaline conditions. First, proteins reduce Cu²⺠to Cu¹⺠in a reaction known as the biuret reaction. Second, the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagent chelates the cuprous ion (Cu¹âº), forming a stable, water-soluble purple-colored complex that exhibits a strong absorbance peak at 562 nm [36] [37] [38]. The extent of this color formation is dependent not only on specific amino acids (cysteine, cystine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) but also on the peptide backbone itself, which contributes to greater uniformity across different proteins compared to the Bradford method [36] [38].

Comparative Analysis: Bradford vs. BCA Assays

Selecting the appropriate quantification assay is a critical decision that depends on the nature of the protein sample, the buffer composition, and the required precision. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the key characteristics of the Bradford and BCA assays to guide this selection.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of the Bradford and BCA protein quantification assays.

| Parameter | Bradford Assay | BCA Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Dye-binding to basic amino acids; color shift from brown (465 nm) to blue (595 nm) [34] [35] | Protein-mediated reduction of Cu²⺠to Cu¹âº; chelation by BCA to form purple complex (562 nm) [36] [37] |

| Key Chemical Basis | Ionic/hydrophobic interactions with Arg, Lys, His, Tyr [34] | Biuret reaction; reduction by peptide bonds and specific amino acids (Cys, Cys, Tyr, Trp) [36] [38] |

| Detection Range | 1–200 μg/mL (microplate) [34] | 20–2,000 μg/mL (standard protocol) [36] [37] |

| Sensitivity | High (detects as low as 1–20 μg/mL) [35] | Moderate (detects as low as 5–25 μg/mL) [36] [35] |

| Dynamic Range | Narrower [35] | Broader [35] |

| Assay Time | Rapid (~5–10 minutes) [35] | Longer (30 min at 37°C to 2 hours at RT) [36] [37] [35] |

| Compatibility with Detergents | Low tolerance; high concentrations interfere significantly [35] | High tolerance; compatible with most ionic and non-ionic detergents (e.g., up to 5%) [36] [7] |

| Protein-to-Protein Variation | High variability; response depends on amino acid composition [36] [35] | More consistent; less affected by protein compositional differences [36] [35] |

| Interfering Substances | Detergents (SDS, Triton X-100), strong bases [34] | Reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol), copper chelators (EDTA, EGTA) [36] |

The choice between these two assays can be streamlined into a logical decision-making process. The following workflow diagram outlines the key questions to ask when selecting the optimal method for your samples.

Diagram 1: Protein assay selection workflow.

Protein Extraction for Western Blotting

Effective protein extraction is the foundational step that dictates the success of all subsequent procedures. The primary goal is to solubilize proteins completely while preserving their native state or ensuring proper denaturation for SDS-PAGE, and most critically, preventing proteolytic degradation.

Lysis Buffer Selection

The choice of lysis buffer is dictated by the subcellular localization of the target protein and the required protein state (native or denatured) for downstream analysis. The table below summarizes recommended buffers for different scenarios.

Table 2: Recommended lysis buffers for protein extraction from mammalian cells and tissues.

| Target Protein Location | Recommended Buffer | Buffer Description & Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Cell (Total Protein) | M-PER or T-PER Reagent [7] | Mild, non-denaturing detergent in a bicine buffer. Preserves protein-protein interactions and enzymatic activity. |

| Membrane-Bound, Nuclear, or Mitochondrial | RIPA Lysis Buffer [7] | Harsh, iconic detergent buffer (contains NaCl, NP-40/Triton X-100, sodium deoxycholate, and SDS). Effective for solubilizing difficult proteins. |

| Cytoplasmic | NP-40 Lysis Buffer [7] | Moderate, non-ionic detergent buffer (Tris, NaCl, EDTA, NP-40). Ideal for extracting cytoplasmic proteins while leaving nuclei intact. |

Standardized Extraction Protocol

The following protocol is optimized for the extraction of total protein from adherent mammalian cell cultures for western blotting [7].

Materials Required:

- Ice-cold Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Appropriate ice-cold lysis buffer (see Table 2)

- Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (e.g., Halt Cocktail, Pierce Tablets)

- Cell scraper

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Refrigerated microcentrifuge

Procedure:

- Inhibit Proteolysis: Add protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail to the lysis buffer immediately before use (e.g., 10 µL of 100X cocktail per 1 mL of buffer) [7].

- Wash Cells: Place the culture dish on ice. Aspirate the culture medium and gently wash the cell monolayer with ice-cold PBS to remove serum proteins.

- Lyse Cells: Aspirate the PBS completely. Add ice-cold lysis buffer (~100–200 µL per 10ⶠcells or for a 6-well plate) to the cells. Tilt the plate to ensure complete coverage [7].

- Harvest Lysate: Using a cell scraper, dislodge the cells and transfer the lysate to a pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube. Incubate on ice for 5–15 minutes with occasional vortexing.

- Clarify Lysate: Centrifuge the lysate at approximately 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble cell debris and genomic DNA [7].

- Collect Soluble Protein: Carefully transfer the supernatant (the soluble protein extract) to a new pre-chilled microcentrifuge tube. Discard the pellet.

- Store: The protein extract can be aliquoted and stored at -80°C for long-term preservation. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

Protein Quantification Protocols

Following extraction, precise quantification of the protein concentration in the clarified lysate is mandatory for loading consistent amounts of protein onto SDS-PAGE gels.

BCA Assay Protocol (Microplate Format)

The BCA assay is highly recommended for general-purpose protein quantification, especially when using detergent-containing lysis buffers like RIPA [7].

Materials Required:

- Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Reagents A and B) [36]

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) standards (e.g., 2 mg/mL stock)

- 1X PBS or the same buffer used for sample preparation

- Clear 96-well microplate

- Microplate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 562 nm

Procedure:

- Prepare Standard Curve: Serially dilute the BSA stock in the same buffer as your unknown samples to create a standard curve covering the range of 0 to 2000 µg/mL. A typical 8-point curve includes 0, 25, 125, 250, 500, 750, 1000, and 1500 µg/mL standards [38].

- Prepare Working Reagent (WR): Mix 50 parts of BCA Reagent A with 1 part of BCA Reagent B (50:1, A:B ratio). Prepare sufficient volume for 200 µL per well [7] [38].

- Pipette Samples: Add 25 µL of each standard and unknown sample replicate into the wells of the microplate.

- Add Working Reagent: Add 200 µL of the WR to each well. Mix the plate thoroughly on a plate shaker for 30 seconds to ensure homogeneity [7].

- Incubate: Cover the plate and incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes. Alternatively, incubation can be performed at room temperature for 2 hours for higher sensitivity [36] [37].

- Measure Absorbance: Cool the plate to room temperature. Measure the absorbance of each well at 562 nm using a microplate reader [7] [38].

- Calculate Concentration: Generate a standard curve by plotting the average absorbance of each BSA standard against its known concentration. Use the linear regression equation of the standard curve to calculate the protein concentration of the unknown samples, factoring in any dilutions made.

Bradford Assay Protocol (Microplate Format)

The Bradford assay is ideal for quick, sensitive quantification of samples in compatible, detergent-free buffers.

Materials Required:

- Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 dye reagent (Bradford Reagent)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) standards

- 1X PBS or compatible buffer

- Clear 96-well microplate

- Microplate reader capable of measuring absorbance at 595 nm

Procedure:

- Prepare Standard Curve: Prepare BSA standards in the range of 0 to 200 µg/mL (e.g., 0, 10, 20, 40, 80, 120, 160, 200 µg/mL) using a buffer compatible with the dye [34].

- Pipette Samples: Add 5–10 µL of each standard and unknown sample into the microplate wells.

- Add Dye Reagent: Add 250 µL of Bradford dye reagent to each well. Mix thoroughly immediately after addition.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate at room temperature for at least 5 minutes. The color is stable but may begin to fade after approximately 1 hour [37] [34].

- Measure Absorbance: Read the absorbance at or near 595 nm using a microplate reader [34].

- Calculate Concentration: Generate a standard curve and calculate the unknown sample concentrations as described for the BCA assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

A successful western blotting experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents. The following table catalogs the essential materials required for the protein extraction and quantification workflows described in this document.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for protein extraction and quantification.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product (Supplier) |

|---|---|---|

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents co-purifying proteases and phosphatases from degrading target proteins and altering phosphorylation states during extraction. | Halt Cocktail (Thermo Fisher) [7] |

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | A robust, denaturing lysis buffer for efficient extraction of total protein, particularly effective for membrane-bound and nuclear proteins. | RIPA Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) [7] |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | A detergent-compatible kit for accurate colorimetric quantification of total protein concentration based on bicinchoninic acid. | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher) [36] [7] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) Standards | A highly pure, stable protein used to generate a standard curve for relative protein quantification in colorimetric assays. | Albumin Standard (Thermo Fisher) [38] |

| SDS Sample Buffer (Loading Buffer) | Denatures proteins and imparts a negative charge for separation by SDS-PAGE. Contains SDS, a buffer, and a tracking dye. | Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad) [39] |

| SDS-PAGE Gel | A polyacrylamide gel matrix used to separate denatured proteins based on their molecular weight under an electric field. | Precast Protein Gels (Various suppliers) |

| Nitrocellulose or PVDF Membrane | A porous membrane to which separated proteins are transferred from the gel for subsequent antibody probing. | Nitrocellulose Membrane (Cell Signaling Technology) [39] |

| Degrasyn | Degrasyn, CAS:856243-80-6, MF:C19H18BrN3O, MW:384.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dehydrocholic Acid | Dehydrocholic Acid, CAS:81-23-2, MF:C24H34O5, MW:402.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Even with optimized protocols, researchers may encounter challenges. Adhering to best practices can prevent common issues and ensure data integrity.

- Addressing Interference in BCA Assays: The BCA assay is susceptible to interference from reducing agents and copper chelators. If your sample contains DTT, β-mercaptoethanol, or EDTA, consider [36]:

- Dilution: Diluting the sample to a point where the interfering substance no longer affects the assay.

- Reagent Adjustment: Increasing the amount of Reagent B (Cu²âº) in the working reagent to compensate for chelators (e.g., 4 mL Reagent B per 100 mL Reagent A instead of 2 mL).

- Protein Precipitation: Precipitating proteins using cold acetone or TCA to remove interfering substances, then redissolving the pellet in a compatible buffer.

- Ensuring Accurate Pipetting: Viscous or foamy samples, particularly those containing SDS, can lead to significant pipetting errors. To mitigate this, use a single pipette tip per sample and withdraw the sample only once, avoiding repeated aspirations with the same tip [38].

- Validating the Standard Curve: The accuracy of quantification hinges on a high-quality standard curve. Always use a fresh serial dilution of the standard protein (typically BSA) and ensure the correlation coefficient (R²) of the curve is greater than 0.95 [34]. For precise quantification of an unknown protein, select a standard protein that is similar in composition to your sample (e.g., use bovine gamma globulin for antibody samples) [38].

- Sample Preparation for Electrophoresis: After quantification, prepare samples for SDS-PAGE by mixing the protein lysate with SDS sample buffer and a reducing agent (e.g., DTT). Heat the samples at 70–100°C for 5–10 minutes to ensure complete denaturation [7] [39]. It is critical to load equal masses of protein (e.g., 20–40 µg) per lane, not equal volumes, to enable direct comparison.

The journey to a successful and publication-quality western blot begins long before the electrophoresis power supply is turned on. It is rooted in the rigorous optimization of protein extraction and quantification. The BCA assay emerges as the more robust and versatile choice for most western blotting applications, particularly due to its superior tolerance for the detergents essential for effective protein solubilization and its reduced protein-to-protein variability [36] [35]. Conversely, the Bradford assay offers a valuable tool for rapid, sensitive quantification of samples in simple, detergent-free buffers [35]. By understanding the principles, advantages, and limitations of each method, and by adhering to the detailed protocols and best practices outlined in this document, researchers can establish a solid foundation for their SDS-PAGE and western blotting experiments, ensuring the generation of reliable, reproducible, and meaningful scientific data.

Within the framework of SDS-PAGE for western blotting sample preparation, proper protein denaturation is a critical prerequisite for obtaining reliable and interpretable results. The processes of boiling and the use of reducing agents work in concert to dismantle the native structure of proteins, ensuring they are linearized and uniformly coated with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). This is essential for achieving separation based primarily on molecular weight during electrophoresis [40] [26]. Failure to optimize these steps can lead to protein aggregation, degradation, or incomplete denaturation, which subsequently compromises band resolution, antibody recognition in western blotting, and the accuracy of molecular weight estimation [40] [41]. This application note provides detailed protocols and data-driven guidelines to standardize sample denaturation for research and drug development applications.

The Role of Denaturation in SDS-PAGE

The fundamental goal of sample preparation for SDS-PAGE is to convert complex, three-dimensional protein structures into linear, negatively charged polypeptides. This transformation is achieved through a combination of chemical and physical treatments.

The anionic detergent SDS plays a dual role: it disrupts hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, effectively unfolding the protein, and it binds to the polypeptide backbone at a relatively constant ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1 g of protein [42]. This binding confers a uniform negative charge density, masking the protein's intrinsic charge and allowing migration through the polyacrylamide gel to be determined almost solely by molecular size [26] [43]. The rate of migration is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the molecular weight, enabling size estimation [42].

However, SDS alone is insufficient to break down all structural elements. Disulfide bonds, which covalently link cysteine residues, can maintain tertiary or quaternary structure. The addition of reducing agents, such as Dithiothreitol (DTT) or β-mercaptoethanol (BME), is necessary to reduce these disulfide bonds, separating polypeptide chains and enabling complete linearization [40] [41]. The final step, heat denaturation (boiling), provides the kinetic energy required to overcome stabilizing interactions and ensures that proteins are fully denatured before entering the gel [41]. The synergy of SDS, reducing agents, and heat is what makes SDS-PAGE a powerful tool for protein analysis.

Optimized Boiling Protocols

While a standard boiling condition of 95–100°C for 5 minutes is effective for many proteins, a one-size-fits-all approach can be detrimental to specific protein classes [40]. The following protocols and table summarize optimized conditions tailored to different protein characteristics.

Standard Boiling Protocol

This protocol is suitable for most routine proteins, particularly small to medium-sized soluble proteins.

- Materials: Protein lysate, Laemmli sample buffer (1X final concentration; containing 2% SDS, glycerol, bromophenol blue, and 62.5 mM Tris-HCl at pH 6.8) [42], reducing agent (e.g., 100 mM DTT or 5% β-mercaptoethanol), heating block or water bath.

- Method:

- Mix the protein lysate with an equal volume of 2X Laemmli sample buffer. For a final volume of 25 µL, combine 12.5 µL of lysate with 12.5 µL of 2X buffer [43].

- Add a reducing agent if not already present in the buffer. For example, add DTT to a final concentration of 10-100 mM or β-mercaptoethanol to 1-5% [43].

- Vortex the mixture briefly and centrifuge to collect the contents at the bottom of the tube.

- Heat the samples at 95–100°C for 5 minutes in a heating block or boiling water bath [40].

- Briefly centrifuge the boiled samples (e.g., 3 minutes) to pellet any insoluble debris and remove condensation [40] [43].

- The samples are now ready to be loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel or stored at -20°C for later use.

Specialized Boiling Conditions

Table 1: Optimized Denaturation Conditions for Specific Protein Types

| Protein Type | Temperature | Duration | Key Rationale | Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Proteins | 95–100 °C | 5 min | Ensures complete denaturation for accurate molecular weight separation. | [40] |

| Large Proteins (>150 kDa) | 70 °C | 5–10 min | Prevents aggregation that can hinder gel entry and migration. | [40] |

| Heat-Sensitive Proteins | 70 °C | 5–10 min | Reduces risk of degradation or loss of antigenicity for sensitive epitopes. | [40] |