Extracting Active Proteins from Native Gels: A Guide to Protocols, Applications, and Troubleshooting for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the extraction of active proteins from native polyacrylamide gels.

Extracting Active Proteins from Native Gels: A Guide to Protocols, Applications, and Troubleshooting for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the extraction of active proteins from native polyacrylamide gels. It covers the foundational principles of native electrophoresis, including Blue-Native (BN-PAGE), Clear-Native (CN-PAGE), and related techniques essential for preserving protein structure and function. Detailed, validated protocols for protein extraction, in-gel activity assays, and downstream applications are presented. The scope also addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for challenging samples, concluding with methods for validating extraction success and comparing the performance of different native gel approaches to inform experimental design in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Native PAGE: Principles for Preserving Protein Activity and Quaternary Structure

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a fundamental technique in protein science used to separate proteins in their biologically active state. Unlike its denaturing counterpart (SDS-PAGE), Native PAGE does not use denaturing agents, thereby preserving protein conformation, subunit interactions, and enzymatic activity [1] [2]. This method is indispensable for research focused on extracting and studying active proteins, as it allows for the separation of protein complexes and functional oligomers based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape [1]. The core principle hinges on the fact that, under native conditions, a protein's migration through a polyacrylamide gel matrix is influenced by both its net charge at the running buffer pH and the frictional force it encounters, which is determined by its size and three-dimensional structure [1]. This application note details the principles, protocols, and key applications of Native PAGE within the context of active protein research.

Core Separation Mechanisms

The separation mechanism in Native PAGE is a composite effect of several protein properties and gel characteristics.

Influence of Net Charge

In alkaline running buffers, most proteins carry a net negative charge, causing them to migrate towards the anode. The charge density (net charge per unit mass) is a primary driver of migration; a protein with a higher negative charge density will migrate faster through the gel [1]. Unlike SDS-PAGE, where SDS confers a uniform negative charge, the inherent charge of the protein under the specific buffer conditions dictates its electrophoretic mobility.

Influence of Size and Shape

Simultaneously, the polyacrylamide gel acts as a molecular sieve. The cross-linked polymer matrix creates pores that present a frictional force to migrating proteins [1]. Smaller and more compact proteins navigate these pores more easily and migrate faster, whereas larger proteins or complex shapes are impeded, resulting in slower migration [1]. The final position of a protein band is thus a result of its charge-to-mass ratio and its interaction with the gel matrix [1].

Table 1: Key Factors Governing Protein Migration in Native PAGE

| Factor | Effect on Separation | Contrast with SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Net Charge | Proteins with higher negative charge density migrate faster. | Protein charge is masked by uniform SDS coating. |

| Size & Mass | Larger proteins migrate slower due to increased frictional drag. | Separation is primarily by molecular mass. |

| Shape/Conformation | Compact proteins migrate faster than extended ones of the same mass. | Proteins are denatured into linear chains; shape is irrelevant. |

| Quaternary Structure | Multimeric complexes are typically preserved and separated as intact units. | Complexes are dissociated into individual subunits. |

Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Native PAGE Workflow

The following workflow outlines the key steps for performing a standard Native PAGE separation for active protein analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Gel Preparation

Native PAGE gels are typically composed of a resolving gel (pH ~8.8) overlaid by a stacking gel (pH ~6.8) with a lower acrylamide concentration [1]. The discontinuous buffer system concentrates the protein samples into sharp bands before they enter the resolving gel, enhancing resolution.

Resolving Gel (8%, 10 mL recipe):

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide solution (30%) — 2.7 mL

- 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 — 2.5 mL

- Water — 4.7 mL

- 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) — 50 µL

- TEMED — 10 µL

- Pour between glass plates and overlay with water-saturated butanol for polymerization.

Stacking Gel (4%, 5 mL recipe):

- Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide solution (30%) — 0.67 mL

- 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 — 1.25 mL

- Water — 3.0 mL

- 10% APS — 25 µL

- TEMED — 5 µL

- After resolving gel sets, pour stacking gel and insert sample comb.

Sample Preparation

Crucially, samples for Native PAGE are not boiled and are prepared in a non-denaturing buffer without SDS or reducing agents [2].

- Mix protein sample with an equal volume of 2x Native Sample Buffer (e.g., 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 0.01% Bromophenol Blue).

- Gently mix by inversion. Do not heat the sample.

- Centrifuge briefly to collect the contents at the bottom of the tube.

Electrophoresis

- Load samples and appropriate native molecular weight markers into the wells.

- Fill the electrode chambers with a native running buffer (e.g., Tris-Glycine, pH ~8.3-8.8, without SDS).

- Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 100-150 V) in a cooled apparatus (4-10°C) to minimize protein denaturation and proteolysis [1].

- Stop electrophoresis when the dye front approaches the bottom of the gel.

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis and Protein Recovery

Following separation, proteins can be visualized and recovered while maintaining activity.

- Detection: Use sensitive stains like Coomassie Blue or SYPRO Ruby. For functional analysis, perform an in-gel activity assay if applicable (e.g., zymography for enzymes) [1].

- Recovery of Active Proteins: To extract active proteins from the gel, excise the band of interest and use passive diffusion (soaking in an appropriate elution buffer) or electro-elution [1]. The resulting protein can be used for downstream functional studies.

Advanced Native PAGE Techniques

For complex samples, particularly membrane proteins, advanced Native PAGE variants offer superior resolution.

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Native PAGE Techniques

| Technique | Key Feature | Optimal Use Case | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Native (BN-PAGE) | Uses anionic Coomassie dye to confer charge and solubilize complexes [3]. | Analysis of protein-protein interactions and large membrane protein complexes (100 kDa - 10 MDa) [3]. | The dye may disrupt weak interactions and can quench fluorescence [3]. |

| Clear Native (CN-PAGE) | No charged dye; relies on protein's intrinsic charge [3]. | Studying highly sensitive complexes where dye might be disruptive; maintains supermolecular structures [3]. | Lower resolution for proteins with high pI (>7); best for acidic proteins [3]. |

| Quantitative Preparative Native Continuous (QPNC-PAGE) | High-resolution separation in a specialized continuous buffer system [3]. | Isolation of active metalloproteins or correctly folded soluble proteins bound to cofactors [3]. | Requires specialized equipment and buffers. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Native PAGE and Active Protein Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Forms the cross-linked porous gel matrix that acts as a molecular sieve [1]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer | Provides the appropriate pH for electrophoresis and protein stability [1]. |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) & TEMED | Catalyzes the free-radical polymerization of acrylamide to form the gel [1]. |

| Glycine | Key component of the discontinuous buffer system, acting as a trailing ion for stacking [4]. |

| Glycerol | Increases sample density for easy well loading in the sample buffer. |

| Tracking Dye (Bromophenol Blue) | Visual marker to monitor electrophoresis progress without interfering with separation. |

| Coomassie G-250 | The anionic dye used in BN-PAGE to solubilize proteins and confer negative charge [3]. |

| Digitonin | A mild detergent used in CN-PAGE to solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native complexes [3]. |

| (-)-Dicentrine | (-)-Dicentrine, CAS:28832-07-7, MF:C20H21NO4, MW:339.4 g/mol |

| Dichloramine-T | Dichloramine-T, CAS:473-34-7, MF:C7H7Cl2NO2S, MW:240.11 g/mol |

Experimental Design and Data Interpretation

Critical Parameters for Success

- pH Control: The pH of the running buffer is critical as it determines the net charge of the protein. A miscalculation can lead to proteins migrating in the wrong direction or not migrating at all [1].

- Temperature: Running the gel in a cooled environment is essential to prevent heat-induced denaturation and aggregation, which can distort bands or lead to loss of activity [1].

- Acrylamide Concentration: The percentage of acrylamide determines the effective separation range. Lower percentages (e.g., 6-8%) are better for large proteins and complexes, while higher percentages (e.g., 10-12%) provide better resolution for smaller proteins [1].

Logical Pathway for Method Selection

The choice of Native PAGE method depends on the research question and sample type. The following diagram outlines a decision-making workflow.

Within the field of proteomics and mitochondrial research, the analysis of native protein complexes is crucial for understanding fundamental cellular processes. The extraction of active proteins from their native gel environment allows for the functional and structural study of intricate cellular machinery. Blue Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) and Clear Native Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (CN-PAGE) are two pivotal techniques developed for this purpose [5] [6]. Originally described by Schägger and von Jagow in 1991, BN-PAGE has become an indispensable tool for resolving enzymatically active membrane protein complexes [5]. This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of these two techniques, framed within the context of extracting active proteins for downstream analysis, complete with structured protocols, quantitative comparisons, and essential methodological workflows for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Technical Principles and Comparative Analysis

Core Principles of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

BN-PAGE relies on the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250, which binds non-covalently to the surface of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic protein residues [5] [7]. This binding imposes a negative charge shift on the proteins, forcing even basic proteins to migrate towards the anode during electrophoresis at pH 7.0 [5]. The dye also prevents aggregation of hydrophobic proteins by keeping them soluble in the absence of detergent during the run [5]. The charge imposed is generally proportional to the protein's mass, aiding in separation according to size in the polyacrylamide gradient gel, with a separation range spanning from 100 kDa to 10 MDa [6].

In contrast, CN-PAGE is a variant that typically replaces the Coomassie blue dye in the cathode buffer with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents to induce the necessary charge shift for migration [5]. In CN-PAGE, the migration distance depends on both the protein's intrinsic charge and the pore size of the gradient gel, which complicates the estimation of native masses compared to BN-PAGE [8]. A key advantage is the absence of residual blue dye, which can interfere with downstream techniques like in-gel enzyme activity staining or fluorescence-based analyses [5] [8].

Direct Technical Comparison

The following table summarizes the key technical differences and applications of the two methods, providing a guide for selecting the appropriate technique.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE Techniques

| Parameter | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Charge System | Coomassie Blue G-250 dye [5] | Mixed anionic/neutral detergents or protein intrinsic charge [5] [8] |

| Resolution | High resolution of individual complexes [8] | Usually lower resolution than BN-PAGE [8] |

| Mass Estimation | Accurate, based on dye-binding proportionality [5] | Less accurate, depends on intrinsic charge and size [8] |

| Downstream Compatibility | Potential dye interference with activity assays/FRET [8] [6] | Superior for in-gel activity staining, FRET, MS [5] [8] |

| Mildness | Can dissociate some labile assemblies [8] | Milder; retains labile supramolecular assemblies [8] |

| Key Application | Standard analysis of individual OXPHOS complexes [5] [9] | Resolving labile supercomplexes, active enzyme assays [5] [8] |

| Typical Detergent for Solubilization | n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (for individual complexes) or digitonin (for supercomplexes) [5] | Often digitonin, sometimes in mixture with other mild detergents [8] [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Core BN-PAGE Protocol

The following workflow details a standardized BN-PAGE protocol adapted for the analysis of mitochondrial complexes from cultured cells or small tissue samples [5] [9].

Sample Preparation

- Isolation: Isolate mitochondria from cells or tissues. While whole tissue/cell extract can be used, mitochondrial isolation is recommended for a stronger signal [9].

- Solubilization: Resuspend 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 μL of Buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin) [9].

- Detergent Treatment: Add 7.5 μL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (for individual complexes) or digitonin (for supercomplexes) [5]. Mix and incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

- Clarification: Centrifuge at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes (a bench-top microcentrifuge at ~16,000 x g can be used, though it is not ideal) [9].

- Staining: Collect the supernatant and add 2.5 μL of a 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [9].

Gel Electrophoresis

- Gel Casting: Manually cast a native linear gradient polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 4–16% or 3–12%). A 6–13% gradient is also highly recommended for broad separation [5] [9]. Alternatively, commercial precast gels can be used (e.g., Thermo Fisher Scientific NativePAGE Bis-Tris gel system) [5].

- Buffer System: Use an anode buffer (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and a blue cathode buffer (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G, pH 7.0) [9].

- Running Conditions: Load 5–20 μL of prepared sample per well. Run the gel at 150 V for approximately 2 hours, or until the blue dye front has almost migrated off the gel, at 4°C [9].

Core CN-PAGE Protocol

The CN-PAGE protocol shares many steps with BN-PAGE, with critical modifications to preserve complex integrity and avoid dye interference [5] [8].

- Sample Preparation: Follow the BN-PAGE sample preparation steps from mitochondrial solubilization to clarification. Omit the addition of Coomassie Blue G-250 to the supernatant [5].

- Gel Casting: Identical to BN-PAGE. The same gradient gels can be used.

- Buffer System: The key difference lies in the cathode buffer. For CN-PAGE, use a "clear" cathode buffer containing mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents instead of Coomassie dye [5] [8].

- Running Conditions: Load the sample and run the gel under conditions identical to BN-PAGE.

Downstream Applications

Following the first-dimension separation, multiple downstream pathways are available for analysis.

- Western Blotting: The native gel lane can be electroblotted onto a PVDF membrane. It is recommended to use a fully submerged transfer system with Tris-Glycine buffer containing 10% methanol [9].

- In-Gel Activity Staining: For CN-PAGE or destained BN-PAGE gels, specific activity stains can be applied to visualize the enzymatic activity of complexes like ATP synthase (Complex V) or cytochrome c oxidase (Complex IV) [5].

- Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis (2D-BN/SDS-PAGE):

- Excise a lane from the first-dimension native gel.

- Soak the strip in SDS denaturing buffer (e.g., containing 2% SDS and 50 mM DTT) to denature the complexes.

- Place the strip horizontally on top of an SDS-PAGE gel (e.g., 10-20% gradient) for the second dimension separation, resolving the individual subunits of the complexes [5] [9].

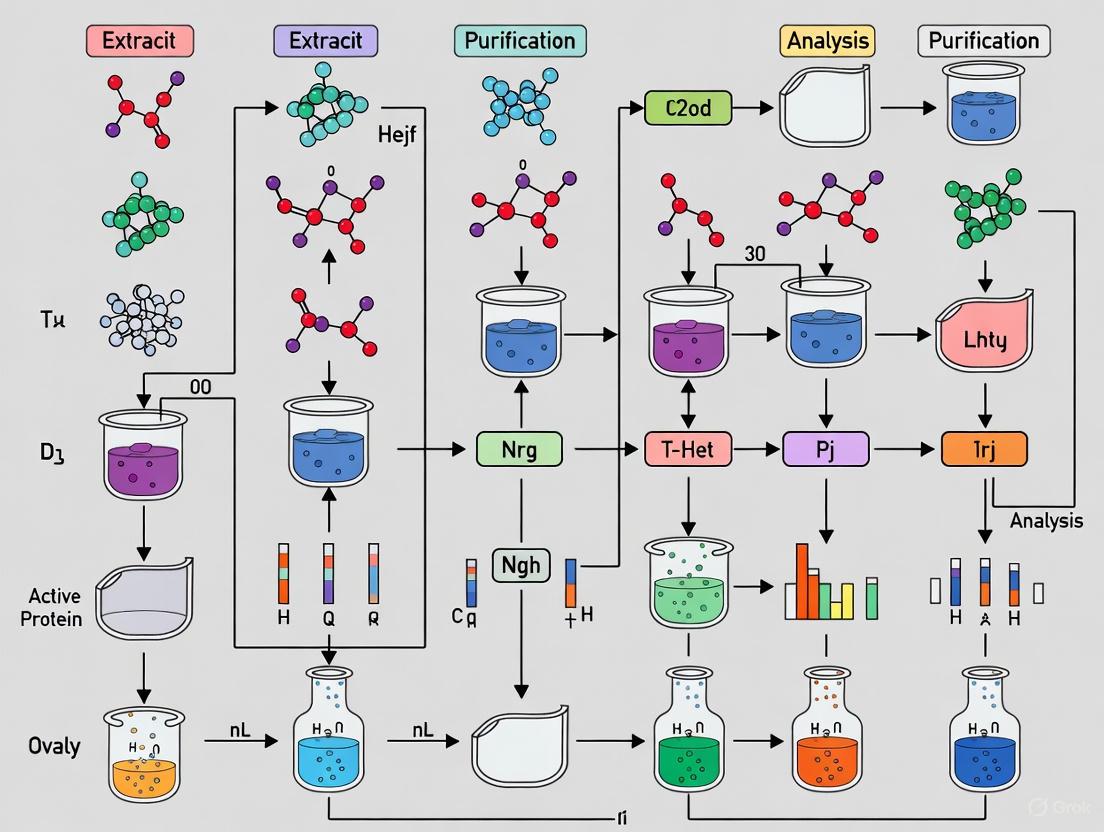

The logical workflow and the relationship between these techniques and their downstream applications are summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE and their downstream applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of native PAGE experiments relies on specific, high-quality reagents. The following table catalogs the essential solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent/Buffer | Function & Purpose | Typical Composition / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Solubilization Detergents | Mildly solubilizes membranes while preserving protein-protein interactions within complexes. | n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (for individual complexes) [5]; Digitonin (for supercomplexes) [5]; Detergent mixture (e.g., 1% β-DM + 1% digitonin for megacomplexes) [7] |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid Buffer | Provides a zwitterionic, low-conductivity environment; supports solubilization and improves resolution. | 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl, pH 7.0 [5] [9] |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 Dye | Imparts negative charge to proteins, enables migration in BN-PAGE, prevents aggregation. | 0.02% in cathode buffer; 5% solution for sample staining [5] [9] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of protein complexes during extraction. | 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL pepstatin [9] |

| BN-PAGE Cathode Buffer | Provides the anionic front and charge for BN-PAGE separation. | 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G, pH 7.0 [9] |

| CN-PAGE Cathode Buffer | Provides the charge for migration without Coomassie dye interference. | Mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents [5] [8] |

| SDS Denaturing Buffer | Denatures complexes for second-dimension SDS-PAGE. | 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris, 50 mM DTT, 0.002% Bromophenol blue, pH 6.8 [9] |

| Dicloxacillin | Dicloxacillin|Beta-lactamase Resistant Penicillin|RUO | Dicloxacillin is a penicillinase-resistant penicillin antibiotic for research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Diethylcarbamazine Citrate | Diethylcarbamazine Citrate, CAS:1642-54-2, MF:C10H21N3O.C6H8O7, MW:391.42 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Investigating Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes and Megacomplexes

The combination of gentle digitonin solubilization with CN-PAGE is particularly powerful for resolving labile respiratory chain supercomplexes (e.g., I-III2-IVn respirasomes) and photosynthetic megacomplexes in thylakoid membranes, which might be dissociated under standard BN-PAGE conditions [8] [7]. For instance, applying a detergent mixture of 1% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside plus 1% digitonin and a 4.3–8% gel gradient has been shown to effectively separate large Photosystem I (PSI) containing megacomplexes, such as PSI-NADH dehydrogenase-like complexes, providing critical insights into functional interactions in energy transduction systems [7].

Quantitative Evaluation of Complexes

For quantitative comparison of complexes across different samples or physiological conditions, densitometric analysis of BN/CN-PAGE gels can be performed. This requires careful attention to several factors [7]:

- Application of equal protein loads based on accurate quantification.

- Correct baseline determination in the densitograms.

- Use of evaluation methods to deconvolute complexes that co-migrate closely. These approaches allow for the calculation of absolute/relative amounts of complexes and their distribution among different oligomeric forms, providing stoichiometric insights essential for diagnostic and research applications [7] [6].

BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE are complementary techniques that form the cornerstone of native protein complex analysis. BN-PAGE remains the gold standard for high-resolution analysis and mass estimation of stable complexes, while CN-PAGE is the preferred method for investigating labile superassemblies and performing in-gel enzymatic assays without dye-related interference. The choice between them should be guided by the biological question, the stability of the complexes of interest, and the desired downstream application. By providing robust, semi-quantitative, and reproducible results, these techniques continue to be indispensable for advancing our understanding of cellular energy conversion mechanisms, the pathologic basis of metabolic diseases, and the functional organization of the cellular complexome.

Within functional proteomics research, the primary goal is not only to identify proteins but also to understand their biological activity, interactions, and regulation. For studies aimed at extracting active proteins, native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) is an indispensable tool. Unlike denaturing methods that use sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to disrupt non-covalent bonds, native PAGE separates proteins under conditions that preserve their delicate three-dimensional structures, subunit interactions, and bound cofactors [10]. This capability allows researchers to directly probe the functional state of macromolecular complexes as they exist in the cell. This application note details the practical advantages of native gels, supported by quantitative data, and provides validated protocols for using this technology to study enzymatically active proteins and their complexes in the context of active protein research.

Core Advantages and Key Applications

The fundamental advantage of native gel electrophoresis is its capacity to maintain proteins in their functional, native state during separation. This provides researchers with a powerful platform for functional analysis that is not possible with denaturing techniques.

Retention of Enzymatic Activity: Because the protein structure remains intact, enzymes separated by native PAGE often retain their catalytic function. This enables in-gel activity assays where the enzymatic activity can be visualized directly as a colored precipitate within the gel matrix [11]. This has been successfully applied to various mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes (MOPCs) and other enzymes.

Preservation of Bound Cofactors: Native electrophoresis preserves the association between proteins and their essential non-protein components. Research on Medium-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (MCAD), a flavoprotein, demonstrated that its bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor remains associated with the protein during high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE), which is crucial for its catalytic function [12].

Analysis of Quaternary Structure and Complexes: Native PAGE separates proteins based on their size, charge, and shape, allowing the resolution of different oligomeric states. This is critical for studying multimeric proteins. For instance, MCAD functions as a homotetramer, and native gels can distinguish this active tetramer from inactive, misfolded aggregates or fragmented subunits caused by pathogenic variants [12]. This technique is also extensively used to resolve the five oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes and their higher-order assemblies, known as supercomplexes [5].

The table below summarizes the types of functional analyses enabled by native gel electrophoresis.

Table 1: Functional Analyses Enabled by Native Gel Electrophoresis

| Analysis Type | Description | Key Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| In-Gel Enzymatic Assay | Direct visualization of enzyme activity via precipitate formation in the gel. | Activity staining for Mitochondrial Complexes IV and V [11]. |

| Protein Complex Stoichiometry | Determination of the native molecular weight and oligomeric state. | Separation of MCAD tetramers from dimers/monomers [12]. |

| Protein-Protein Interactions | Identification of stable interactions within macromolecular complexes. | Analysis of Polycomb Repressor Complex 2 (PRC2) from cellular fractions [13]. |

| Impact of Genetic Variants | Assessment of how mutations affect complex assembly and function. | Studying clinically relevant MCAD variants (e.g., p.R206C, p.K329E) [12]. |

Quantitative Data from Recent research

Recent studies have provided robust quantitative evidence supporting the use of native gels for sensitive and linear functional assays.

A 2025 study on MCAD developed a high-resolution clear native PAGE (hrCN-PAGE) colorimetric in-gel activity assay. The researchers quantified the enzymatic activity of the MCAD tetramer separately from other forms, demonstrating a linear correlation between the amount of protein loaded, its FAD content, and the resulting enzymatic activity for the physiological substrate, octanoyl-CoA [12]. This linearity was maintained with less than 1 µg of protein, highlighting the assay's high sensitivity.

Table 2: Quantitative Data from MCAD In-Gel Activity Assay [12]

| Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | Linear activity detected with <1 µg of purified recombinant MCAD. | Suitable for analyzing scarce protein samples from tissues or cell cultures. |

| Correlation Coefficient | Linear correlation between protein amount and in-gel activity (R² not provided in extract, but relationship is explicitly linear). | Enables quantitative densitometry for comparative studies of enzyme activity. |

| Variant Analysis | Pathogenic variants (p.K329E, p.R206C) showed disrupted tetramer migration and inactive lower-mass species. | Allows simultaneous assessment of structural integrity and catalytic function of mutant proteins. |

Another study emphasized the utility of continuous monitoring of in-gel kinetics, revealing complex catalytic behaviors such as a significant lag phase in Complex V (ATP synthase) activity that would be missed in single endpoint measurements [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-Gel Activity Assay for MCAD

This protocol, adapted from recent research, details the steps for visualizing MCAD activity after hrCN-PAGE [12].

Sample Preparation:

- Source: Use purified recombinant protein or mitochondrial-enriched fractions from cell homogenates.

- Solubilization: Gently solubilize membranes using a mild, non-ionic detergent like n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) to preserve protein complexes.

- Preparation: Mix the sample with NativePAGE sample buffer and the provided 5% G-250 additive [14].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Gel Type: Perform electrophoresis using a 4–16% high-resolution clear native (hrCN) polyacrylamide gel.

- Conditions: Use the appropriate anode and cathode buffers as per the commercial hrCN-PAGE or NativePAGE system instructions. Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 150 V) for approximately 1-2 hours at 4°C until the dye front migrates to the bottom.

Activity Staining:

- Incubation: Immediately after electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a reaction solution containing:

- Substrate: 0.1-1.0 mM octanoyl-CoA (physiological MCAD substrate).

- Electron Acceptor: 0.5-1.0 mM Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT).

- Buffer: A suitable buffer at pH 7-8.

- Detection: Active MCAD oxidizes the substrate, transferring electrons to NBT, which is reduced to an insoluble, purple-colored diformazan precipitate. Bands of activity typically become visible within 10–15 minutes of incubation.

- Termination: Stop the reaction by rinsing the gel with distilled water.

- Incubation: Immediately after electrophoresis, incubate the gel in a reaction solution containing:

Analysis:

- Capture an image of the gel and perform densitometric analysis of the activity bands using software such as ImageJ or ImageLab.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol 2: Monitoring In-Gel Enzyme Kinetics

This protocol describes a system for continuous monitoring of enzymatic activity within a native gel, providing comprehensive kinetic data [11].

Custom Chamber Setup:

- Assembly: Secure the native gel to the bottom of a custom reaction chamber.

- Circulation: Connect the chamber to a peristaltic pump to continuously circulate the reaction media over the surface of the gel.

- Filtration: Incorporate an in-line filter to remove turbidity caused by reaction byproducts, ensuring clear optical observation.

Image Acquisition:

- Use a high-resolution digital camera mounted above the chamber.

- Program the system to collect time-lapse images of the gel at regular intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) throughout the reaction.

Data Processing:

- Analysis: Use image processing routines to correct for background deposition and generate kinetic traces of the in-gel activity over time.

- Kinetics: Analyze the resulting time-course data to identify distinct kinetic phases, such as lag phases, initial linear rates, and saturation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful native gel electrophoresis relies on specific reagents to maintain protein solubility, confer charge, and enable activity detection.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native Gel Electrophoresis and In-Gel Assays

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Principle | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| NativePAGE Bis-Tris Gel System [14] | Provides near-neutral pH and uses Coomassie G-250 to charge proteins, preventing aggregation of membrane proteins. | Ideal for membrane proteins and hydrophobic complexes. |

| Mild Detergents (DDM, Digitonin) [5] [15] | Solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving protein-protein interactions and complex integrity. | Digitonin is milder and better for supercomplex analysis; DDM is for individual complexes. |

| Coomassie G-250 Dye [14] | Binds hydrophobically to proteins, imparting a negative charge for migration and preventing aggregation. | Used in BN-PAGE; can be removed for clearer in-gel activity assays. |

| Nitro Blue Tetrazolium (NBT) [12] | A colorimetric electron acceptor that forms a purple precipitate upon reduction in oxidoreductase assays. | Used in assays for dehydrogenases like MCAD. |

| Diaminobenzidine (DAB) [11] | A chromogen that forms an insoluble brown polymer when oxidized by cytochrome c in Complex IV assays. | Essential for in-gel histochemical staining of cytochrome c oxidase. |

| Diflomotecan | Diflomotecan|Topoisomerase I Inhibitor|For Research | Diflomotecan is a novel homocamptothecin and potent topoisomerase I inhibitor with enhanced lactone stability. This product is for research use only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Diflunisal | Diflunisal|COX Inhibitor|Research Chemical | Diflunisal is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and COX inhibitor for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

Workflow Integration and Data Interpretation

Integrating native gel electrophoresis into a broader research workflow maximizes its potential. A typical functional proteomics pipeline is illustrated below.

When interpreting results, researchers should be aware of the following:

- Migration Shifts: Altered migration can indicate changes in complex size, shape, or stability, as seen with the pathogenic MCAD variant R206C, where the tetramer migrated at an apparently lower molecular mass [12].

- Multiple Active Bands: The presence of several active bands may represent different oligomeric states or supercomplex assemblies, all of which can be catalytically competent.

- Quantitative Kinetics: Continuous monitoring can reveal complex kinetics, such as lag phases, which provide deeper insight into the enzyme's catalytic mechanism under the constraints of the gel matrix [11].

Within the framework of research dedicated to extracting active proteins from native gels, the precise selection of electrophoretic components is paramount. Unlike denaturing techniques, native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) preserves the higher-order structure, enzymatic activity, and non-covalent cofactors of proteins, enabling functional analysis post-separation. This application note details the critical roles of detergents, dyes, and buffers in successful native electrophoresis. We provide a comparative analysis of Blue Native (BN)-PAGE, Clear Native (CN)-PAGE, and the emerging Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), alongside structured protocols and workflows. The methodologies outlined are designed to guide researchers in selecting the optimal conditions for extracting and analyzing functionally intact proteins, particularly for applications in drug discovery and fundamental proteomic research.

The recovery of active, native proteins from an electrophoretic gel is a cornerstone technique for biochemical characterization, functional studies, and drug target validation. The foundation of this process is native PAGE, a technique that separates protein complexes based on their size, charge, and shape without disrupting their tertiary or quaternary structure [16] [17]. The success of this method—and the subsequent activity of the extracted protein—hinges on the specific chemical environment created by detergents, dyes, and buffers during electrophoresis.

Standard SDS-PAGE employs the anionic detergent sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) to denature proteins, linearize them, and impart a uniform negative charge, effectively separating polypeptides by molecular weight alone [18] [17]. However, this process obliterates enzymatic activity, dissociates non-covalently bound subunits, and strips away essential metal ions [19]. In contrast, native PAGE techniques use milder reagents to maintain proteins in their functional state. This allows for the separation of intact metalloproteins and active enzymes, making it an indispensable tool for researchers focused on protein function rather than mere composition [19]. This note delineates the components and protocols that make such analyses possible.

Core Components of Native Electrophoresis Systems

The integrity of isolated protein complexes is governed by the specific reagents used in the electrophoresis system. Their functions extend beyond mere solute transport to active roles in protein solubilization, charge modification, and complex stabilization.

Detergents: Solubilization and Selectivity

Detergents are amphipathic molecules essential for extracting membrane proteins from lipid bilayers and keeping them soluble in aqueous solutions during electrophoresis [18]. The choice of detergent is critical and determines which protein complexes remain intact.

- Ionic Detergents (e.g., SDS): In standard SDS-PAGE, SDS denatures proteins by binding to the polypeptide backbone and imparting a strong negative charge. In native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE), however, the SDS concentration is drastically reduced (e.g., to 0.0375% in the running buffer and omitted from the sample buffer) [19]. This minimal SDS concentration aids in separation and prevents aggregation but is insufficient to cause full denaturation, thereby allowing many enzymes to retain their activity.

- Non-Ionic Detergents (e.g., n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, DDM): These are the detergents of choice for BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE. They effectively solubilize membrane proteins by forming micelles around hydrophobic domains while leaving the native structure and protein-protein interactions intact [5] [9]. Digitonin, another non-ionic detergent, is even milder and is specifically used to preserve the integrity of fragile supercomplexes, such as mitochondrial respirasomes [5].

Table 1: Common Detergents in Native Electrophoresis and Their Properties

| Detergent | Type | Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) | Primary Use in Native PAGE | Impact on Protein Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Non-ionic | ~0.15 mM | BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE; general membrane protein solubilization | Preserves native structure and protein-protein interactions |

| Digitonin | Non-ionic | ~0.2-0.5 mM | BN-PAGE; stabilization of labile supercomplexes (e.g., respiratory chain) | Very mild; maintains weak interactions within supercomplexes |

| SDS | Anionic (Ionic) | ~1.4-2.1 mM (~0.1%) | NSDS-PAGE (at low conc.); standard SDS-PAGE (at high conc.) | Minimal denaturation in NSDS-PAGE; complete denaturation in SDS-PAGE |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic | ~0.2-0.3 mM | Alternative for some CN-PAGE protocols | Preserves native structure, but can disrupt some protein interactions |

Dyes and Charge Shift Agents

In native electrophoresis, a key challenge is to ensure that all proteins, including very hydrophobic ones, migrate towards the anode with high resolution. This is achieved through charge-shift agents.

- Coomassie Blue G-250 (Serva Blue G): This is the defining component of BN-PAGE. The dye binds non-covalently to the surface of hydrophobic proteins, imparting a strong negative charge that facilitates migration into the gel at neutral pH [5] [9]. It also prevents protein aggregation during electrophoresis, leading to sharper bands. A significant drawback is that the dye can inhibit enzymatic activity and interfere with in-gel fluorescence detection [20].

- Mixed Micelles in CN-PAGE: To overcome the limitations of Coomassie dye, high-resolution CN-PAGE replaces it with non-colored mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer [20]. These mixed micelles induce a similar charge shift, enhancing protein solubility and migration without the inhibitory effects of the blue dye. This makes CN-PAGE the preferred method for subsequent in-gel catalytic activity assays and fluorescence studies [5] [20].

Buffers: Creating the Native Environment

The buffer systems in native PAGE are carefully formulated to maintain a non-denaturing pH and provide the ionic environment necessary for stable protein complexes.

- Bis-Tris/Tricine Systems: These are the most common buffering compounds. Bis-Tris, with a pKa of ~6.5, provides excellent buffering capacity at the neutral pH (pH 7.0-7.5) required to preserve native protein structure [19] [9].

- Aminocaproic Acid: This zwitterionic salt is a key additive in BN-PAGE buffers. It acts as a "shielding agent," presumably by competing with proteins for binding to detergent micelles, thereby preventing excessive protein dissociation and aggregation during the solubilization and electrophoresis processes [5] [9].

Table 2: Key Buffer Components and Their Functions in Native PAGE

| Buffer Component | Typical Concentration | Function | Example Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bis-Tris | 50-100 mM | Primary buffering agent; maintains neutral pH to preserve native structure | BN-PAGE, NSDS-PAGE [19] [9] |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | 0.5-1.0 M | Shielding agent; improves solubilization of membrane complexes and prevents aggregation | BN-PAGE Sample Buffer [5] [9] |

| Tricine | 50 mM | Counter-ion in cathode buffer; facilitates protein migration | BN-PAGE Cathode Buffer [9] |

| MOPS/Tris | 50 mM each | Running buffer system for NSDS-PAGE; milder alternative to standard SDS-PAGE buffers | NSDS-PAGE Running Buffer [19] |

| Glycerol | 5-10% | Sample buffer additive; increases density for gel loading and stabilizes proteins | Common in various sample buffers [19] |

Comparative Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Choosing the appropriate native electrophoresis technique is critical and depends on the balance required between resolution and functional preservation.

Technique Comparison: BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE, and NSDS-PAGE

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the optimal native electrophoresis method based on research goals.

Figure 1: A workflow to guide the selection of native PAGE methods. CN-PAGE is optimal for functional assays, NSDS-PAGE offers the highest resolution, and BN-PAGE is a robust default for complex analysis.

- Blue Native (BN)-PAGE: This method provides a robust balance between resolution and complex integrity, making it ideal for analyzing the subunit composition and assembly of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes [5] [9]. However, the Coomassie dye can be problematic for downstream activity assays.

- Clear Native (CN-PAGE): As a variant of BN-PAGE, CN-PAGE omits the Coomassie dye from the sample and cathode buffer, often replacing it with non-colored detergents [20]. This preserves the catalytic activity of enzymes, enabling high-sensitivity in-gel activity staining for complexes like ATP synthase and, for the first time, respiratory Complex III [5] [20]. The resolution can be slightly lower than BN-PAGE.

- Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE): This hybrid technique uses drastically reduced SDS concentrations (e.g., 0.0375% in running buffer) and omits the heating denaturation step [19]. It achieves a resolution of complex proteomic mixtures comparable to denaturing SDS-PAGE while allowing a significant portion of enzymes to retain activity. One study demonstrated Zn²⺠retention increased from 26% to 98% compared to standard SDS-PAGE, with seven out of nine model enzymes remaining active [19].

Detailed Protocol: BN-PAGE for Functional Complex Analysis

The following protocol is adapted from established methods [5] [9] and is designed for the analysis of mitochondrial complexes, with a focus on downstream protein extraction and activity assays.

Stage 1: Sample Preparation (Mitochondrial Extract)

- Solubilization: Resuspend 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 µL of ice-cold buffer A (0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0, supplemented with protease inhibitors: 1 mM PMSF, 1 µg/mL leupeptin, 1 µg/mL pepstatin) [9].

- Detergent Addition: Add 7.5 µL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM). Mix gently and incubate on ice for 30 minutes.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized mixture at 72,000 x g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material.

- Dye Addition: Collect the supernatant and add 2.5 µL of a 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid. The sample is now ready for loading.

Stage 2: First-Dimension BN-PAGE

- Gel Casting: Prepare a linear gradient gel (e.g., 4-16% or 6-13% acrylamide) using a gradient maker. The gel solution contains acrylamide/bis-acrylamide, 1 M aminocaproic acid, 1 M Bis-Tris (pH 7.0), and is polymerized with APS and TEMED [5] [9].

- Electrophoresis:

- Anode Buffer (Lower Chamber): 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0.

- Cathode Buffer (Upper Chamber): 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G-250, pH 7.0.

- Load the prepared samples (5-20 µL).

- Run the gel at 150 V for approximately 2 hours at 4°C until the blue dye front migrates to the bottom of the gel.

Stage 3: Downstream Processing for Active Protein Extraction

- In-Gel Activity Staining: For enzymatic validation, immediately after electrophoresis, incubate the gel in specific substrate mixtures to visualize active complexes [5] [21]. For example, Complex V (ATP synthase) activity can be detected by a lead phosphate precipitation method in the presence of ATP.

- Electroelution for Protein Recovery: To extract active proteins, carefully excise the band of interest. Place the gel slice in an electroelution device with a suitable native buffer (e.g., 50 mM Bis-Tris, 50 mM Tricine, pH 7.0). Apply a mild electric field (e.g., 100 V for 2 hours) to migrate the native protein out of the gel slice into the recovery chamber. The resulting protein solution can be concentrated and buffer-exchanged for further functional studies.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Native Electrophoresis and Protein Recovery

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Composition |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild, non-ionic detergent for solubilizing membrane protein complexes in BN-PAGE | 10% solution in water [9] |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Charge-shift agent for BN-PAGE; provides negative charge and prevents aggregation | 5% solution in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [9] |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Shielding agent in buffers to prevent protein aggregation and improve resolution | 1 M stock solution, pH 7.0 [5] |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Protects protein samples from degradation during extraction and electrophoresis | PMSF, Leupeptin, Pepstatin in ethanol/water [9] |

| NativeMark Unstained Standards | Unstained protein molecular weight standards for native PAGE | Thermo Fisher Scientific [19] |

| Linear Gradient Gel (e.g., 4-16%) | Provides optimal separation of protein complexes across a wide molecular weight range | Hand-cast or commercial pre-cast gels [5] |

| Electroelution Device | Apparatus for extracting native proteins from excised gel bands post-electrophoresis | Various commercial systems available |

The strategic application of specialized detergents, dyes, and buffers is the bedrock of successful native electrophoresis and the subsequent recovery of active proteins. BN-PAGE remains a powerful tool for robust complex separation, CN-PAGE is superior for direct in-gel functional assays, and NSDS-PAGE offers a unique combination of high resolution and functional preservation. The protocols and comparisons provided here equip researchers with the knowledge to rationally design their experimental approach. Mastering these components is essential for any research program aimed at extracting and characterizing functionally intact proteins from biological systems, thereby providing a direct path from gel separation to biochemical and pharmacological analysis.

Within the framework of research focused on extracting active proteins, selecting the appropriate electrophoretic separation technique is a critical foundational step. The core objective of this application note is to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear rationale for choosing native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE or BN-PAGE) over denaturing methods. This choice is paramount when the experimental goal extends beyond simple molecular weight determination to the preservation of a protein's native, biologically active state. The integrity of higher-order structure—quaternary interactions, enzymatic function, and cofactor binding—is the defining factor in this decision, enabling the study of protein complexes, functional enzymes, and metabolic pathways in their physiologically relevant forms [22] [23].

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

The fundamental distinction between native and denaturing gel electrophoresis lies in the treatment of the protein's structure. Denaturing gels, such as SDS-PAGE, employ strong ionic detergents (e.g., Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate, SDS) and reducing agents (e.g., DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) combined with heat to fully unfold proteins into linear chains. This process obliterates the protein's secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures, resulting in separation based almost exclusively on molecular mass [24] [22] [25]. In contrast, native gel electrophoresis is performed in the absence of denaturing agents. This approach preserves the protein's intricate three-dimensional conformation, allowing separation to be governed by a combination of the protein's intrinsic charge, molecular mass, and shape [22] [26] [23].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Native vs. Denaturing Gel Electrophoresis

| Characteristic | Native-PAGE | Denaturing (SDS)-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Treatment | No SDS or reducing agents; no heating [25] [23] | Heated with SDS and a reducing agent [22] [25] |

| Protein State | Native, folded structure [26] | Denatured, linearized polypeptide [26] |

| Separation Basis | Mass, intrinsic charge, and 3D shape [22] [23] | Primarily molecular mass of the polypeptide chain [22] |

| Quaternary Structure | Preserved; multimeric complexes remain intact [22] [23] | Disrupted; complexes are dissociated into subunits [25] |

| Biological Activity | Often retained post-electrophoresis [22] | Lost [22] |

| Molecular Weight Determination | Not accurate, as charge and shape influence migration [23] | Accurate, based on comparison to linear standards [22] |

The following decision pathway provides a visual guide for selecting the appropriate electrophoretic method based on research objectives:

Ideal Applications for Native Gel Electrophoresis

The unique ability of native gels to maintain proteins in their functional state makes them the indispensable technique for several advanced research applications.

Analysis of Protein Quaternary Structure and Complexes

Native-PAGE is the premier method for investigating the subunit composition and stoichiometry of multimeric proteins. Unlike SDS-PAGE, which dissociates complexes into individual subunits, native gels maintain the non-covalent interactions between subunits, allowing the intact complex to be separated and analyzed [22] [23]. This is crucial for studying oligomerization states, such as dimers, trimers, or higher-order assemblies. A prominent example is the use of Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) to resolve the individual complexes of the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system and, when solubilized with mild detergents like digitonin, to analyze their organization into even larger functional units known as respirasomes or supercomplexes [5].

Isolation of Enzymes with Preserved Activity

When the experimental endpoint requires a functional protein, native electrophoresis is the only suitable choice. By avoiding denaturants that destroy the active site, the native conformation and thus the catalytic function of enzymes are maintained throughout the separation process [24] [22]. This enables researchers to isolate active enzymes directly from complex mixtures. Following electrophoresis, functional enzymes can be detected through in-gel activity assays, where the gel is incubated with specific substrates to produce a localized colorimetric or fluorescent signal, directly linking a protein band to its biochemical function [5].

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

Native gels provide a powerful, though often underutilized, tool for probing protein-protein interactions. The migration of a protein complex through the gel matrix will differ from that of its individual components. By analyzing shifts in band mobility or the appearance of new, higher molecular weight bands under different conditions (e.g., with/without a binding partner), researchers can gather evidence of interaction and study binding events in a native-like environment [24].

Table 2: Application-Based Selection Guide for Native Gel Electrophoresis

| Research Objective | Recommended Method | Key Rationale | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Determine Aggregation State | Native-PAGE | Preserves non-covalent subunit interactions, revealing native oligomeric state [25] [23] | Studying dimerization of transcription factors; analyzing oligomeric states of membrane receptors [23] |

| Isolate Active Enzyme | Native-PAGE | Maintains 3D conformation of the active site, preserving catalytic function [22] [25] | Purification of active proteases, kinases, or metabolic enzymes for functional assays [24] [23] |

| Study Protein Complexes | BN-PAGE / Native-PAGE | Resolves intact macromolecular assemblies without dissociating them [5] | Analysis of respiratory chain supercomplexes [5], RNA-protein complexes, or viral capsids |

| Characterize Charge Isoforms | Native-PAGE / CN-PAGE | Separation depends on intrinsic charge, revealing different post-translationally modified forms [5] | Resolving glycoprotein variants or phosphoprotein isoforms |

| Determine Polypeptide Molecular Weight | SDS-PAGE | Denatures and linearizes proteins, making migration dependent on chain length [22] [23] | Confirming recombinant protein size; assessing sample purity and integrity [24] [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: BN-PAGE for Complex Analysis

This protocol, adapted from validated methodologies, is designed for the analysis of protein complexes from cell cultures, such as mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for BN-PAGE Analysis of Protein Complexes

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild, non-ionic detergent for solubilizing membrane proteins without disrupting protein-protein interactions [5] | Critical for extracting individual OXPHOS complexes. Concentration must be optimized. |

| Digitonin | Very mild, non-ionic detergent used for solubilizing supercomplexes [5] | Used instead of DDM when the goal is to preserve higher-order supercomplexes. |

| 6-Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; stabilizes proteins during extraction and improves resolution by regulating buffer conductivity [5] | Helps prevent protein aggregation and maintains native pH. |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Anionic dye that binds hydrophobic protein surfaces, imparting a uniform negative charge shift and enhancing protein solubility during electrophoresis [5] | The "Blue" in BN-PAGE. Use in cathode buffer and sample. |

| Bis-Tris Buffer System | Buffering agent for gel and running buffers at neutral pH (e.g., pH 7.0-7.5) [5] | Avoids pH extremes that could denature labile complexes. |

| Gradient Gel (e.g., 3-12%) | Polyacrylamide gel with increasing concentration; pores are larger at the top for high-MW complexes and smaller at the bottom for resolution [5] | Essential for separating a broad range of complex sizes simultaneously. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Sample Preparation (Cell Lysis and Complex Solubilization)

- Harvest cells and wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Pellet cells by centrifugation.

- Resuspend the cell pellet in an appropriate ice-cold hypotonic buffer or mitochondrial isolation buffer.

- For total membrane protein extraction, add the mild detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) to a final concentration of 1-2% (w/v) from the cell pellet wet weight. To preserve supercomplexes, use digitonin at 2-4 g/g protein.

- Incubate on ice for 10-30 minutes with gentle agitation to solubilize membranes and release protein complexes.

- Clarify the lysate by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 x g for 15-20 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant contains the solubilized protein complexes.

Step 2: Sample Preparation for Loading

- Mix the solubilized protein supernatant with a loading buffer containing 5% Coomassie Blue G-250 and 50 mM 6-aminocaproic acid.

- Do not heat the samples. Keep them on ice until loading.

Step 3: Gel Electrophoresis (BN-PAGE)

- Use a pre-cast or hand-cast linear gradient polyacrylamide gel (e.g., 3-12%).

- Prepare the anode (lower chamber) and cathode (upper chamber) running buffers as specified for BN-PAGE. The cathode buffer typically contains a low concentration (e.g., 0.02%) of Coomassie Blue G-250.

- Load the prepared samples and molecular weight markers for native complexes.

- Run the gel at a constant voltage (e.g., 80-150 V) or constant current (e.g., 15-20 mA) for 2-4 hours, preferably at 4°C to prevent heat-induced denaturation. Start with a lower voltage until the samples enter the resolving gel, then increase the voltage for the remainder of the run.

Step 4: Post-Electrophoresis Analysis

- For in-gel activity staining: Immediately after electrophoresis, incubate the gel in specific substrate solutions to visualize the activity of complexes like Complex I, IV, or V [5].

- For western blotting: Transfer proteins to a membrane for immunodetection with specific antibodies.

- For two-dimensional analysis (2D BN/SDS-PAGE): Excise a lane from the BN-PAGE gel, incubate it in SDS-PAGE sample buffer to denature the complexes, and place it horizontally on top of an SDS-PAGE gel for separation in the second dimension by subunit molecular weight [5].

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Native Gels

Successful native-PAGE requires careful attention to detail to preserve protein activity and integrity.

- Problem: Smearing or Poor Band Resolution

- Problem: Distorted Bands ("Smiling" or "Frowning")

- Problem: Loss of Enzymatic Activity

- Problem: Protein Aggregation and Failure to Enter the Gel

- Cause: Insufficient detergent for solubilization or precipitation.

- Solution: Optimize the detergent-to-protein ratio. The addition of Coomassie G-250 in BN-PAGE helps prevent aggregation by coating proteins [5].

The strategic selection of native gel electrophoresis is a cornerstone of research aimed at understanding protein function within the context of their native structure. When the scientific question involves protein complexes, quaternary architecture, or enzymatic activity, native-PAGE and its advanced variant, BN-PAGE, provide unparalleled insights that denaturing methods cannot offer. By adhering to the optimized protocols and troubleshooting guidance outlined in this document, researchers can reliably extract and analyze active proteins, thereby driving forward discoveries in structural biology, enzymology, and therapeutic development.

Step-by-Step Protocols for Extraction and Functional Analysis of Active Proteins

The success of any proteomics study, particularly those aimed at analyzing active proteins or complexes from native systems, is fundamentally dependent on the initial steps of sample preparation. Efficient and reproducible protein extraction from tissues and cultured cell lines forms the critical foundation for downstream analyses, including native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), mass spectrometry, and functional studies. Variations in extraction efficiency can significantly impact protein yield, proteome coverage, and the integrity of protein complexes, ultimately determining the reliability and biological relevance of the data. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to optimized sample preparation protocols, comparing various methods for protein extraction and digestion to support research on extracting active proteins from native polyacrylamide gels.

Comparative Analysis of Sample Preparation Methods

Performance Evaluation of Digestion Methods for Cell Lines

A systematic comparison of three common digestion methods for bottom-up proteomics of a macrophage cell line (THP-1) revealed that all methods can yield robust results across a wide range of starting materials, with careful standardization [29]. The Filter-Aided Sample Preparation (FASP) method using passivated filter units demonstrated superior performance in terms of identified peptides and proteins, though all methods showed good reproducibility [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Digestion Methods for Cell Line Proteomics

| Method | Key Features | Identified Proteins | Reproducibility (CV) | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FASP | Detergent removal via filtration, on-membrane digestion | Highest number | Median CV: 8-9% [29] | Compatible with detergent-containing buffers; high efficiency | Requires specialized devices; multiple steps |

| In-Solution Digestion | Direct digestion in solution | Intermediate | Median CV: 9-10% [29] | Simple protocol; low cost | Sensitive to detergents; requires desalting |

| In-Gel Digestion | Separation before digestion, in-gel proteolysis | Lower than FASP | Median CV: 8% [29] | Effective contaminant removal; compatible with various buffers | Time-consuming; potential incomplete extraction |

Protein Extraction Efficiency from Different Tissues

The optimal protein extraction protocol varies significantly depending on the sample origin, particularly when comparing cultured cells to complex tissues. For challenging plant tissues like olive leaves, an SDS-based denaturing protocol (Method A) demonstrated superior performance, providing the highest protein yields and uniquely identifying 77 proteins compared to CHAPS-based (Method B) and TCA/acetone (Method C) methods [30]. Similarly, for human skin samples, an optimized protocol combining chemical and mechanical lysis with a buffer containing 2% SDS, 50 mM TEAB, and protease/phosphatase inhibitors enabled identification of approximately 6,000 proteins, significantly enhancing coverage of the cutaneous proteome [31].

Table 2: Tissue-Specific Protein Extraction Protocols and Performance

| Tissue Type | Optimal Method | Lysis Buffer Composition | Homogenization | Protein Identifications | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olive Leaf [30] | Denaturing SDS (Method A) | SDS-based denaturing buffer | Not specified | 77 unique proteins | Plant proteomics; hydrophobic protein analysis |

| Human Skin [31] | Chemical/Mechanical | 2% SDS, 50 mM TEAB, protease/phosphatase inhibitors | Matrix A beads + FastPrep-24 5G homogenizer | ~6,000 proteins | Skin biology; biomarker discovery |

| Liver Tissue [29] | Manual Lysis | RIPA buffer (SDC + SDS + NP-40) | Manual homogenization | High coverage | Metabolic studies; tissue proteomics |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimized Protein Extraction from Cell Lines

For comprehensive proteomic profiling of cancer cell lines, including preparation for native PAGE applications, the following protocol has been validated for 54 widely used cancer cell lines derived from various tissues [32]:

Cell Culture and Lysis:

- Grow cells to 80-90% confluence under appropriate conditions.

- Wash cells twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Harvest cells using trypsinization or scraping as appropriate.

- For lysis, use RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Incubate on ice for 30 minutes with occasional vortexing.

- Centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Collect supernatant for protein quantification and downstream applications.

Protein Digestion Options:

- For FASP digestion: Process 100 μg of protein extract using 30 kDa molecular weight cutoff filters [29].

- For in-solution digestion: Dilute protein extract to reduce detergent concentration below critical micelle concentration [29].

- For in-gel digestion: Separate proteins by SDS-PAGE, excise bands, and perform standard in-gel digestion [29].

Blue Native PAGE for Active Protein Complexes

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) preserves protein complexes in their native state, making it ideal for studying mitochondrial complexes, respiratory chain supercomplexes, and other multisubunit assemblies [5] [9]. The following protocol has been validated for >20 years and optimized for small patient samples [5]:

Mitochondrial Isolation and Solubilization:

- Isolate mitochondria from cells or tissues by differential centrifugation.

- Resuspend 0.4 mg of sedimented mitochondria in 40 μL of 0.75 M aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [9].

- Add 7.5 μL of 10% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) for complex solubilization [9].

- Mix and incubate for 30 minutes on ice.

- Centrifuge at 72,000 × g for 30 minutes (or 16,000 × g for small volumes) [9].

- Collect supernatant and add 2.5 μL of 5% Coomassie blue G in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid [9].

BN-PAGE Electrophoresis:

- Prepare a linear gradient native gel (6-13% acrylamide) using a gradient former [9].

- Use a stacking gel containing 4.2% acrylamide, 0.25 M aminocaproic acid, and 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 [9].

- Load samples (5-20 μL) and run at 150 V for approximately 2 hours using anode (50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) and cathode (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie blue G, pH 7.0) buffers [9].

- For second-dimension analysis, excise BN-PAGE lanes and soak in SDS denaturing buffer before loading onto SDS-PAGE gels [9].

Tube-Gel Sample Preparation Protocol

The tube-gel (TG) method offers a versatile alternative for sample preparation, particularly compatible with various extraction buffers and suitable for large-scale quantitative proteomics [33]:

Tube-Gel Preparation:

- Extract proteins using preferred buffer (Laemmli buffer recommended for reference protocol).

- Mix protein extract with acrylamide solution and polymerization agents.

- For chemical polymerization: Use ammonium persulfate (APS) and TEMED.

- For photopolymerization: Use riboflavin and UV exposure for polymerization, especially for pH-sensitive applications.

- Allow complete polymerization (approximately 30 minutes).

- Wash polymerized tube-gels extensively with washing buffer (e.g., 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate in 20% ethanol) to remove detergents and contaminants.

- Digest proteins in-gel using trypsin (enzyme-to-protein ratio 1:50) overnight at 37°C.

- Extract peptides and desalt before LC-MS/MS analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Extraction and Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detergents | SDS, n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside, CHAPS, NP-40 | Protein solubilization; membrane protein extraction | Compatibility with downstream applications; removal requirements |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF, leupeptin, pepstatin, commercial cocktails | Prevent protein degradation during extraction | Broad-spectrum vs. specific inhibitors; compatibility with assays |

| Lysis Buffers | RIPA, SDC-based, Laemmli, TEAB | Protein extraction and stabilization | Denaturing vs. native conditions; MS-compatibility |

| Chromatography Media | EVtrap beads, exoEasy membranes, ÄKTA columns | EV isolation; protein complex purification | Yield vs. specificity; automation compatibility |

| Electrophoresis Consumables | Precast gels, gradient gels, BN-PAGE reagents | Protein separation; complex analysis | Resolution needs; native vs. denaturing conditions |

| Digallic Acid | Digallic Acid - XOD/URAT1 Dual Inhibitor|CAS 536-08-3 | Bench Chemicals | |

| Dihydrocurcumin | Dihydrocurcumin (DHC) | Dihydrocurcumin is a major bioactive metabolite of curcumin. This product is for research use only (RUO). Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Visualization

Technical Considerations and Applications

Method Selection Criteria

Choosing the appropriate sample preparation method depends on several factors, including sample type, protein properties, and analytical goals. For tissues with high lipid content or inhibitory compounds (e.g., olive leaves), denaturing SDS-based protocols provide superior extraction efficiency [30]. For membrane protein complexes, BN-PAGE offers unique advantages for preserving native interactions [5] [9]. When working with limited sample amounts, the tube-gel method demonstrates excellent performance even with 1 μg of starting material [33].

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Comprehensive proteomic profiling using optimized sample preparation methods enables critical applications in drug development, including target identification, mechanism of action studies, and biomarker discovery. The integration of phosphoproteomic and glycoproteomic data, as demonstrated in the multi-level analysis of 54 cancer cell lines, provides insights into kinase activation patterns and therapeutic vulnerabilities [32]. Similarly, optimized EV isolation methods coupled with proteomic and glycomic analysis reveal molecular alterations in cancer-derived EVs with potential diagnostic and therapeutic implications [34].

Optimized sample preparation is the cornerstone of successful proteomics research, particularly for studies aiming to extract and analyze active proteins from native systems. The protocols and comparisons presented in this application note provide researchers with evidence-based guidance for selecting and implementing appropriate methods for their specific experimental needs. As proteomic technologies continue to advance, further refinements in sample preparation will undoubtedly enhance our ability to characterize complex proteomes and extract biologically relevant information from both tissues and cell lines.

Guidelines for Manual Casting and Running High-Resolution Native Mini-Gels

Within the context of a broader thesis on extracting active proteins from native polyacrylamide gels, the ability to isolate and study proteins in their native, functional state is paramount. Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (native-PAGE) is a fundamental technique that enables the separation of protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions, thereby preserving their biological activity, subunit interactions, and three-dimensional structure [35] [36]. This protocol details the manual casting and execution of high-resolution native mini-gels, specifically focusing on Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Clear Native (CN)-PAGE. These variants are indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals analyzing intricate protein assemblies, such as those in the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system [5] [37], or for conducting subsequent in-gel activity assays to link structure directly to function [38].

Principles of Native Electrophoresis

Unlike denaturing SDS-PAGE, which separates proteins primarily by molecular weight, native-PAGE separates proteins based on a combination of their intrinsic charge, size, and shape under conditions that maintain their native conformation [35]. The charge of the protein is determined by its primary amino acid sequence (isoelectric point) and the pH of the electrophoresis buffer [35].

BN-PAGE, first described by Schägger and von Jagow, uses the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250. This dye binds hydrophobically to proteins, imparting a uniform negative charge shift that facilitates their migration towards the anode and prevents aggregation during electrophoresis [5] [37] [9]. CN-PAGE is a closely related technique where the Coomassie blue dye is replaced by mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer to induce the necessary charge shift [5] [37]. A key advantage of CN-PAGE is the absence of residual blue dye, which can interfere with downstream applications like in-gel enzyme activity staining or intrinsic fluorescence detection [38] [37]. The choice between these methods depends on the experimental goal: BN-PAGE generally offers superior resolution and complex stability, while CN-PAGE is preferred for direct in-gel activity assays or other sensitive downstream detection methods [5] [37].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of BN-PAGE and CN-PAGE

| Feature | BN-PAGE | CN-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Charge-Shift Agent | Coomassie Blue G-250 dye [37] [9] | Mixed anionic/neutral detergent micelles [5] [37] |

| Key Advantage | Excellent resolution and stability of high-MW complexes; robust for 2D analysis [37] [9] | No dye interference; ideal for in-gel activity assays and sensitive detection [38] [37] |

| Key Limitation | Dye can interfere with activity assays and some detection methods [38] [37] | Can be less effective for very hydrophobic protein complexes [5] |

| Ideal Application | Analysis of complex assembly, subunit composition, and supercomplex formation [5] [9] | Functional studies requiring direct enzymatic activity measurement post-separation [38] |

Reagent and Buffer Formulations

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful native gel electrophoresis relies on a specific set of reagents designed to solubilize and stabilize protein complexes without disrupting their native state.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Native-PAGE

| Reagent/Buffer | Function | Composition Example |

|---|---|---|

| Aminocaproic Acid | Zwitterionic salt; provides ionic strength and assists in protein solubilization during extraction [5] [9]. | 0.75 M in Buffer A [9] |

| Bis-Tris | Inert buffering agent; maintains stable pH (~7.0) during electrophoresis [5] [9]. | 50 mM in Anode Buffer [9] |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside (DDM) | Mild, non-ionic detergent; solubilizes membrane proteins while preserving complex integrity [5] [9]. | 10% solution for sample preparation [9] |

| Digitonin | Very mild, non-ionic detergent; used for solubilizing membranes to preserve supercomplexes (e.g., respirasomes) [5] [37]. | Varying concentrations (e.g., 4-8 g/g protein) [37] |

| Coomassie Blue G-250 | Imparts negative charge to proteins for BN-PAGE; prevents aggregation [37] [9]. | 0.02% in Cathode Buffer [9] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents proteolytic degradation of samples during preparation [9]. | PMSF, leupeptin, pepstatin [9] |

Buffer Recipes

Accurate preparation of these buffers is critical for success.

Table 3: Buffer Recipes for Native-PAGE

| Buffer | Composition | pH |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer A (Sample Preparation) | 0.75 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris/HCl [9] | 7.0 |

| BN-PAGE Anode Buffer | 50 mM Bis-Tris [9] | 7.0 |

| BN-PAGE Cathode Buffer | 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, 0.02% Coomassie Blue G [9] | 7.0 |

| CN-PAGE Cathode Buffer | 50 mM Tricine, 15 mM Bis-Tris, plus mixed detergents (e.g., 0.05% sodium deoxycholate, 0.02% DDM) [5] [37] | 7.0 |

| Native Transfer Buffer | 48 mM Tris, 39 mM Glycine, 0.04% (w/v) SDS [36] | ~9.2 |

| SDS Denaturing Buffer | 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 50 mM Tris, 0.002% Bromophenol blue, 50 mM DTT [9] | 6.8 |

Step-by-Step Protocol

Experimental Workflow

Sample Preparation

Isolation and Solubilization: Begin with sedimented mitochondria (e.g., 0.4 mg). Resuspend the pellet in 40 µL of ice-cold Buffer A (0.75 M aminocaproic acid, 50 mM Bis-Tris, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitors (e.g., 1 mM PMSF) [9]. Add 7.5 µL of a 10% solution of the detergent n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) to solubilize the membrane protein complexes. Mix gently and incubate on ice for 30 minutes [9].

Clarification: Centrifuge the solubilized sample at high speed (72,000 x g recommended, or ~16,000 x g in a microcentrifuge as a minimum) for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet insoluble material [9].

Add Charge-Shift Agent: Carefully collect the supernatant. For BN-PAGE, add 2.5 µL of a 5% Coomassie Blue G solution (in 0.5 M aminocaproic acid) to the supernatant [9]. For CN-PAGE, this step is omitted, and the sample is loaded without added dye.

Manual Casting of High-Resolution Linear Gradient Gels

Manual casting of gradient gels provides flexibility and is more economical, improving resolution across a broad molecular weight range [5] [9].

Gel Casting Setup: Thoroughly clean the short and spacer plates with 70% ethanol and assemble them tightly in the casting module to prevent leaks [39].

Gel Solution Preparation: Prepare the low- and high-percentage acrylamide solutions for a linear gradient (e.g., 6–13%) in separate beakers. Use the recipes below, adding TEMED last to catalyze polymerization [9] [39]. Vortex the solutions gently but thoroughly after adding TEMED.

Table 4: Recipes for Manual Casting of a 6-13% Linear Gradient Native Gel (for ~10 gels)

Reagent 6% Acrylamide Solution 13% Acrylamide Solution 30% Acrylamide/Bis (37.5:1) 7.6 mL 14 mL ddH₂O 9 mL 0.2 mL 1 M Aminocaproic Acid, pH 7.0 19 mL 16 mL 1 M Bis-Tris, pH 7.0 1.9 mL 1.6 mL 10% Ammonium Persulfate (APS) 200 µL 200 µL TEMED 20 µL 20 µL - Critical: The APS solution should be freshly prepared daily for optimal polymerization [39].

Pouring the Gradient: Using a two-chamber gradient former connected to a peristaltic pump, create the linear gradient by simultaneously mixing the low-percentage (light) and high-percentage (dense) solutions. Transfer the solution between the glass plates until it reaches the appropriate level [5] [9].

Overlay and Polymerization: Gently overlay the gel solution with a 50% isopropanol solution to ensure a flat interface and prevent drying [9] [39]. Allow the gel to polymerize completely (approximately 30-60 minutes).

Pour Stacking Gel: Once polymerized, pour off the isopropanol and rinse with deionized water. Prepare and cast a native stacking gel (e.g., 4.5%) [36]. Insert the comb without introducing bubbles and allow it to polymerize for 20-30 minutes.

First-Dimension Electrophoresis

Assembly and Loading: Assemble the gel in the electrophoresis tank. Fill the anode and cathode chambers with the appropriate buffers (see Table 3). Load clarified samples (5–20 µL) into the wells [9].

Electrophoresis Conditions: Run the gel at a constant voltage of 100-150 V, keeping the apparatus on ice or in a cold room. Continue the run until the blue dye front (for BN-PAGE) has almost migrated off the bottom of the gel (approximately 1.5-2 hours for mini-gels) [36] [9].

Downstream Applications

In-Gel Enzyme Activity Assay