Decoding the STAT SH2 Domain: From Phosphotyrosine Binding Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting

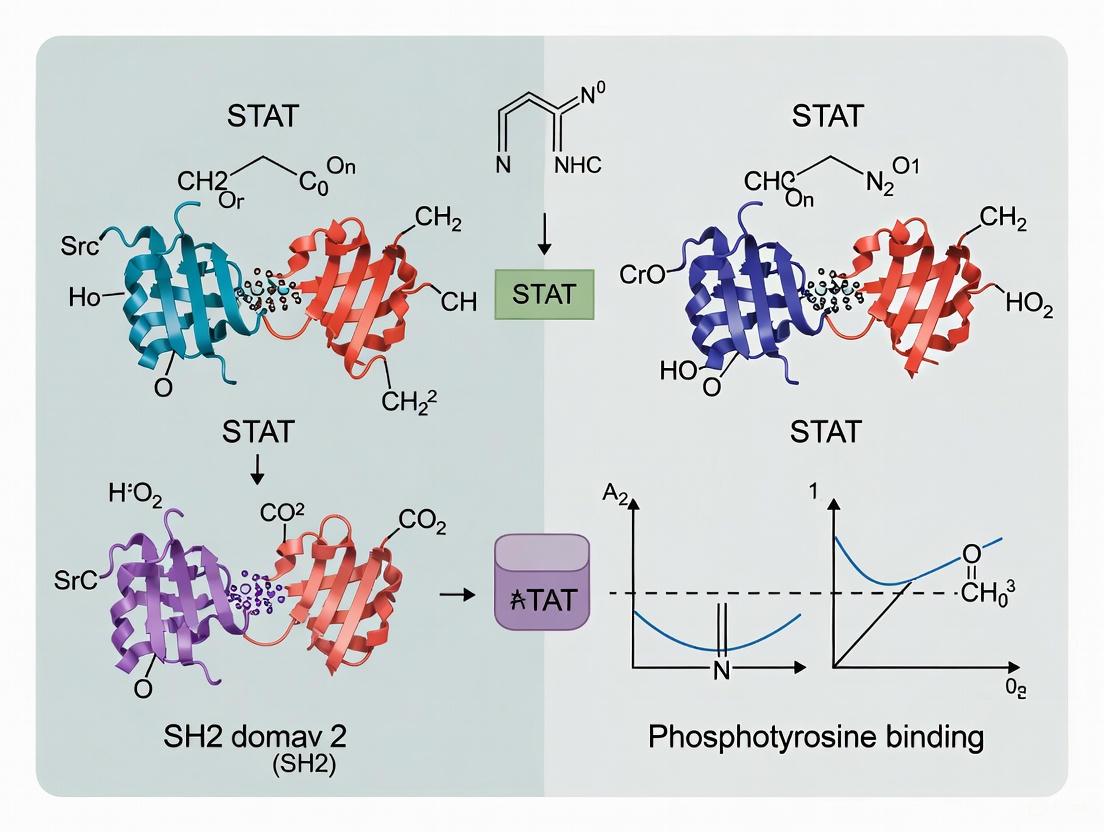

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the STAT SH2 domain, a critical module for phosphotyrosine recognition in cellular signaling.

Decoding the STAT SH2 Domain: From Phosphotyrosine Binding Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the STAT SH2 domain, a critical module for phosphotyrosine recognition in cellular signaling. We explore the unique structural features that distinguish STAT-type from Src-type SH2 domains and detail the molecular mechanisms governing phosphopeptide binding specificity. For researchers and drug development professionals, the content covers emerging methodologies for investigating SH2 domain dynamics, analyzes disease-associated mutations and their mechanistic impacts, and evaluates current strategies for therapeutic targeting. The review also discusses non-canonical functions, including roles in liquid-liquid phase separation and lipid interactions, offering a holistic perspective on STAT SH2 domains as targets for novel clinical interventions in cancer and immune disorders.

The Architectural Blueprint of STAT SH2 Domains and Their Phosphotyrosine Recognition Code

Evolutionary Origins and Metazoan Specificity of SH2 Domains

Src homology 2 (SH2) domains serve as essential phosphotyrosine recognition modules in eukaryotic cell signaling, with their evolutionary expansion closely linked to increasing metazoan complexity. This technical analysis examines the provenance of SH2 domains from early unicellular eukaryotes through metazoan diversification, emphasizing the co-evolution of phosphotyrosine signaling networks. We document the correlation between SH2 domain expansion and tyrosine kinase elaboration, highlighting key adaptations in domain architecture and binding specificity that underpin sophisticated signaling capabilities in complex organisms. The analysis further details experimental methodologies for investigating SH2 domain function and provides strategic considerations for therapeutic targeting of SH2-mediated interactions in disease contexts, particularly focusing on implications for STAT SH2 domain research.

The Src homology 2 (SH2) domain represents a fundamental architectural component in metazoan signal transduction systems, functioning as a specialized "reader" module that recognizes phosphorylated tyrosine residues within specific sequence contexts. With 111 human proteins containing at least one SH2 domain (for a total of 121 domains across the proteome), this domain family facilitates the assembly of precise protein-protein interaction networks in response to tyrosine phosphorylation [1] [2]. SH2 domains operate within an integrated signaling triad comprising "writer" protein-tyrosine kinases (PTKs) that establish phosphorylation marks, "reader" SH2 domains that interpret these marks, and "eraser" protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) that remove phosphorylation [3] [2]. This review examines the evolutionary emergence of SH2 domains and their subsequent functional specialization, with particular emphasis on implications for understanding STAT family SH2 domains and their phosphotyrosine recognition mechanisms.

Evolutionary Provenance of SH2 Domains

Deep Evolutionary Origins

SH2 domains first emerged in early unicellular eukaryotes, with recent genomic analyses revealing their presence in the last eukaryotic common ancestor [3] [4]. The most ancient SH2 domains identified to date reside in the SPT6 transcription elongation factor, which contains tandem SH2 domains that pack against one another and recognize extended phosphorylated serine and threonine peptides of RNA polymerase II [5]. Structural analysis reveals that the N-terminal SH2 domain of SPT6 possesses a near-canonical phospho-binding pocket that recognizes phosphothreonine but can also bind tyrosine, representing a potential evolutionary stepping-stone to dedicated pTyr recognition [5]. This ancestral mechanism demonstrates the evolutionary repurposing of the SH2 fold from phospho-serine/threonine recognition to the specialized phosphotyrosine binding characteristic of metazoan domains.

Expansion Alongside Tyrosine Kinases

Comprehensive genomic surveys across 21 eukaryotic species reveal that SH2 domains co-evolved and expanded alongside protein tyrosine kinases, with a striking correlation coefficient of 0.95 between the percentage of PTKs and SH2 domains in their respective genomes [4]. This coordinated expansion is particularly evident along the unikont branch of eukaryotes, which includes metazoans, choanoflagellates, and amoebozoa [3]. The emergence of the complete complement of pTyr signaling components approximately 900 million years ago at the pre-metazoan boundary suggests that SH2 domain-mediated signaling facilitated the transition to multicellularity [4].

Table 1: Evolutionary Expansion of SH2 Domains and Tyrosine Kinases Across Selected Species

| Organism | SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins | Protein Tyrosine Kinases (PTKs) | Lineage |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae (yeast) | 1 | 0 | Unikont (Fungus) |

| M. brevicollis (choanoflagellate) | 37 | 128 | Unikont (Choanozoa) |

| C. elegans (roundworm) | 70 | 90 | Unikont (Metazoa) |

| D. melanogaster (fruit fly) | 43 | 32 | Unikont (Metazoa) |

| H. sapiens (human) | 111 | ~90 | Unikont (Metazoa) |

Pre-Metazoan CRK Ancestors and Functional Conservation

Investigations of CRK family adapter proteins provide compelling evidence for functional conservation of SH2 domain specificity from pre-metazoan ancestors. Studies of the choanoflagellate Monosiga brevicollis, a unicellular relative of metazoans, identified two CRK/CRKL ancestral (crka) genes [6]. Despite approximately 600 million years of evolutionary divergence, the SH2 domain of M. brevicollis crka1 maintains the ability to bind the mammalian CRK/CRKL SH2 binding consensus phospho-YxxP and recognizes the SRC substrate/focal adhesion protein BCAR1 (p130CAS) in the presence of activated SRC [6]. This remarkable conservation demonstrates the early establishment of specific SH2 recognition codes that persisted throughout metazoan evolution.

Structural and Functional Diversification in Metazoans

Domain Architecture and Functional Specialization

The expansion of SH2 domains in metazoans occurred primarily through gene duplication followed by domain shuffling, creating novel protein architectures that integrated SH2 domains with diverse functional modules [3] [4]. This evolutionary process generated several distinct functional classes of SH2-containing proteins:

Table 2: Major Functional Classes of SH2 Domain-Containing Proteins in Humans

| Functional Class | Representative Proteins | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes | ABL1, SRC, JAK2, PIK3R2, PTPN11 | Kinase, phosphatase, lipid kinase activity |

| Adaptor proteins | CRK, CRKL, GRB2, NCK1, NCK2 | Scaffolding, complex assembly |

| Regulatory proteins | RASA1, VAV1, CHN1 | GTPase activation, signaling regulation |

| Docking proteins | SHC1, BRDG1 | Signal integration, amplification |

| Transcription factors | STAT1, STAT3, STAT5, STAT6 | Gene expression regulation |

| Cytoskeletal proteins | TNS1, TNS3, TENS2 | Cytoskeleton organization, mechanotransduction |

Structural Conservation and Binding Mechanism

Despite sequence diversity, SH2 domains maintain a highly conserved structural fold characterized by a central β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, forming a compact domain of approximately 100 amino acids [7] [2]. The phosphotyrosine recognition mechanism centers on a deeply conserved arginine residue at position βB5 within the characteristic FLVR motif, which forms bidentate hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety of pTyr and provides specificity for phosphotyrosine over phosphoserine/threonine [5] [2]. SH2 domains employ a "two-pronged plug two-holed socket" binding model where the phosphorylated tyrosine inserts into a conserved basic pocket while residues C-terminal to the pTyr (typically positions +1 to +5) engage a specificity pocket that determines sequence selectivity [8] [5].

Atypical SH2 Domains and Functional Diversity

While most SH2 domains adhere to the canonical binding mechanism, several atypical SH2 domains exhibit unusual features that expand their functional repertoire. These include:

- Multiple pTyr recognition sites: Some SH2 domains possess additional basic residues that create secondary phosphopeptide binding sites [5].

- Recognition of unphosphorylated peptides: A subset of SH2 domains can bind specific unphosphorylated sequences under certain conditions [5].

- Dimerization and oligomerization capabilities: Some SH2 domains mediate higher-order assembly through self-association [7].

- Membrane lipid interactions: Approximately 75% of SH2 domains interact with membrane lipids, particularly phosphoinositides, which can modulate their protein interaction capabilities [7].

Experimental Approaches for SH2 Domain Investigation

Deep Mutational Scanning of Regulatory Mechanisms

Recent advances in deep mutational scanning enable comprehensive functional characterization of SH2 domains within multi-domain proteins. A recent study applied this approach to SHP2, a phosphatase containing two SH2 domains that autoinhibit its catalytic domain [9]. The experimental workflow involved:

Library Construction: Saturation mutagenesis libraries for full-length SHP2 (SHP2FL) and isolated phosphatase domain (SHP2PTP) were created using mutagenesis by integrated tiles (MITE), divided into 15 and 7 sub-libraries respectively.

Functional Selection: Libraries were expressed in yeast alongside active Src kinase variants (v-SrcFL or c-SrcKD). SHP2 phosphatase activity rescued yeast from tyrosine kinase-induced growth arrest.

Deep Sequencing: Variant enrichment before and after selection was quantified by deep sequencing to calculate activity scores.

Biochemical Validation: Selected mutants were purified for in vitro phosphatase activity measurements, confirming strong correlation between enrichment scores and catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) [9].

This approach identified hundreds of clinically relevant mutations that disrupt autoinhibitory interfaces and provided insights into allosteric regulation of SH2-containing proteins.

SH2 Domain-Peptide Interaction Analysis

Multiple biophysical and biochemical methods enable detailed characterization of SH2 domain binding properties:

Fluorescence Polarization: Measures changes in fluorescence anisotropy upon peptide binding to determine binding affinities (KD values typically 0.1-10 μM) [2].

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry: Monitors thermal stability shifts upon ligand binding to assess interactions.

SATURATION Transfer Difference NMR: Provides atomic-level information on binding interfaces and conformational changes.

Computational Docking: Rosetta FlexPepDock enables high-resolution modeling of peptide-protein complexes, accounting for peptide conformational flexibility [8].

GST Pulldown Competition Assays: Characterize protein-protein binding interactions in complex biological contexts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Investigations

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta FlexPepDock | Computational peptide-protein docking | Accounts for peptide flexibility, high-resolution modeling |

| Phosphotyrosine peptide libraries | Binding specificity profiling | Covers diverse sequence space, identifies consensus motifs |

| SH2 domain superbinder mutants | Affinity enhancement | Engineered for increased pTyr binding, useful as tools |

| Deep mutational scanning platforms | Functional characterization | High-throughput assessment of mutation effects |

| Yeast viability assays | Functional selection | Links SH2 function to growth phenotype |

| Lipid binding assays | Membrane interaction studies | Measures PIP2/PIP3 interactions |

| Ac-WVAD-AMC | Ac-WVAD-AMC, MF:C35H40N6O9, MW:688.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Cbl-b-IN-9 | Cbl-b-IN-9, MF:C30H33F3N6O2, MW:566.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Therapeutic Targeting and Research Perspectives

SH2 Domains as Therapeutic Targets

The central role of SH2 domains in signal transduction makes them attractive therapeutic targets, particularly in oncology. Several strategies have emerged for targeting SH2-mediated interactions:

Peptide and Peptidomimetic Antagonists: Development of optimized peptide inhibitors based on native binding sequences, such as those targeting the CRK/CrkL-p130Cas axis in tumor cell migration and invasion [8].

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Non-lipidic small molecules that target lipid-protein interactions in SH2 domain-containing kinases like Syk [7].

Allosteric Modulators: Compounds that target regulatory interfaces rather than direct binding pockets, such as those disrupting autoinhibitory interactions in SHP2 [9].

Druggability Assessment: Peptide inhibitors serve as valuable tools for validating targets and assessing druggability even when not developed as therapeutics themselves [8].

Implications for STAT SH2 Domain Research

Research on SH2 domain evolution and function provides critical insights for STAT family studies:

Dimerization Mechanisms: STAT proteins utilize SH2 domain-mediated dimerization for activation, a mechanism that evolved early in metazoan history.

Specificity Determinants: Understanding how SH2 domains achieve specificity for +3 residues informs STAT DNA binding and dimerization specificity.

Therapeutic Targeting: STAT3 SH2 domain inhibitors exemplify the translation of basic SH2 domain knowledge to therapeutic development [8].

Network Evolution: STAT proteins represent one evolutionary trajectory of SH2 domain utilization in transcription factor regulation.

SH2 domains exemplify the evolutionary innovation of modular interaction domains that enabled metazoan cellular complexity. From ancestral origins in pre-metazoan eukaryotes to functional diversification in complex organisms, SH2 domains expanded alongside tyrosine kinases to establish sophisticated phosphotyrosine signaling networks. Their structural conservation coupled with strategic variations in specificity determinants created a versatile recognition system that coordinates diverse signaling pathways. Contemporary research approaches, including deep mutational scanning and structural analysis, continue to reveal new dimensions of SH2 domain function and regulation. The evolutionary insights and experimental methodologies discussed provide a foundation for advancing STAT SH2 domain research and developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting phosphotyrosine signaling networks in human disease.

The Src homology 2 (SH2) domain represents a fundamental architectural unit in eukaryotic cellular signaling, serving as a primary reader of phosphotyrosine (pTyr) post-translational modifications. This approximately 100-amino-acid protein module adopts a characteristic αβββα fold that has been remarkably conserved throughout evolution, from unicellular organisms to humans [4] [10] [11]. The SH2 domain's structural conservation underscores its fundamental role in phosphotyrosine signaling, which co-evolved with protein tyrosine kinases and phosphatases to facilitate the complex cell-cell communication required for metazoan development [4]. Within the broad family of SH2 domains, the STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) subgroup exhibits distinctive structural adaptations that enable its unique function in transcriptional regulation. This technical guide examines the core structural motifs, conserved elements, and functional mechanisms of the characteristic αβββα fold, with specific emphasis on the STAT SH2 domain within the context of ongoing research into phosphotyrosine binding mechanisms.

The Canonical SH2 Domain Architecture

Fundamental Structural Organization

The SH2 domain maintains a conserved structural scaffold organized around a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, forming the signature αβββα topology. The central β-sheet typically consists of three strands (βB, βC, βD) arranged in antiparallel fashion, though many SH2 domains contain additional strands (βA, βE, βF, βG) that augment structural complexity and functional versatility [11]. This core "sandwich" structure positions the β-sheet between two protective α-helices (αA and αB), creating a stable platform for phosphopeptide recognition while protecting the hydrophobic core from solvent exposure.

The N-terminal region of the SH2 domain exhibits higher conservation compared to the C-terminal region, reflecting the critical phosphotyrosine-binding function housed within this segment. The deep phosphate-binding pocket located within the βB strand contains an invariant arginine residue at position βB5 (part of the conserved FLVR sequence motif) that forms essential electrostatic interactions with the phosphorylated tyrosine moiety [10] [11]. The C-terminal region, while more variable, contributes importantly to binding specificity through the formation of hydrophobic pockets that accommodate residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine.

Table 1: Core Secondary Structural Elements of the Canonical SH2 Domain

| Element | Position | Structural Role | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| βB strand | Central | Forms phosphate-binding pocket with invariant ArgβB5 | High |

| βC strand | Central | Part of central antiparallel β-sheet | High |

| βD strand | Central | Part of central antiparallel β-sheet | High |

| αA helix | N-flanking | Stabilizes N-terminal region | Medium-High |

| αB helix | C-flanking | Stabilizes C-terminal region | Medium |

| βE, βF, βG strands | Variable | Present in Src-type, absent in STAT-type SH2 domains | Low |

STAT-Type Versus Src-Type SH2 Domain Structural Variations

SH2 domains are broadly categorized into two major subgroups based on distinct structural features: STAT-type and Src-type domains. This classification reflects evolutionary divergence and functional specialization within the SH2 domain family [12] [11].

STAT-type SH2 domains lack the βE and βF strands present in their Src-type counterparts and feature a split αB helix. This structural simplification may represent an evolutionary adaptation that facilitates SH2 domain-mediated dimerization, a critical step in STAT activation and nuclear translocation [11]. The STAT-type architecture is considered evolutionarily ancient, with primitive forms present in organisms like Dictyostelium that employ phosphotyrosine signaling for transcriptional regulation prior to the emergence of metazoans [12].

Src-type SH2 domains contain the complete complement of secondary structural elements, including the additional βE and βF strands and a continuous αB helix. The presence of these extra elements expands the potential for structural diversity and binding specificity among Src-type domains, which constitute the majority of SH2 domains in the human proteome [11].

Conserved Molecular Interactions in Phosphotyrosine Recognition

The Phosphotyrosine-Binding Pocket

The molecular mechanism of phosphotyrosine recognition represents a masterpiece of evolutionary conservation, centered around a deeply buried invariant arginine residue (ArgβB5) that forms a bidentate salt bridge with two oxygen atoms of the phosphate moiety [10] [11]. This essential interaction is supplemented by additional electrostatic contacts from conserved basic residues including ArgαA2 and LysβD6 in various SH2 domains, though the exact composition varies between families. The remarkable conservation of this phosphate recognition mechanism across diverse SH2 domains highlights its fundamental importance to the domain's function.

Structural analyses reveal that the phosphotyrosine-binding groove is lined by elements from βB, βC, βD, αA, and the BC loop, creating a precisely contoured surface that accommodates the phosphorylated tyrosine side chain while excluding non-phosphorylated residues [10]. The aromatic ring of the phosphotyrosine is further stabilized through cation-π interactions with adjacent basic residues in many SH2 domains, particularly those of the Src family [10].

Specificity-Determining Regions

While the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket provides the essential anchor interaction, specificity for distinct peptide sequences is determined primarily through interactions with residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine. A largely hydrophobic "specificity pocket" delineated by the CD, DE, EF, and BG loops accommodates the pY+1, pY+2, and pY+3 residues of the phosphopeptide, with the exact steric and chemical constraints varying among different SH2 domains [10] [11].

The structural plasticity of these loop regions enables different SH2 domains to recognize distinct optimal peptide sequences, thereby allowing precise discrimination between various phosphorylation sites in the proteome. This modular recognition system—universal phosphotyrosine anchoring coupled with variable specificity determinants—enables the approximately 120 human SH2 domains to collectively recognize and interpret the complex landscape of tyrosine phosphorylation events in cellular signaling [10].

Table 2: Key Conserved Residues and Structural Elements in SH2 Domains

| Element/Residue | Location | Function | Conservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ArgβB5 | βB strand | Bidentate salt bridge with pY phosphate | Invariant (exceptions rare) |

| FLVR motif | βB strand | Phosphate binding and structural integrity | High |

| ArgαA2 | αA helix | pY ring stabilization (Src-family) | Variable |

| BC loop | Between βB-βC | pY binding groove formation | Medium |

| CD loop | Between βC-βD | Specificity pocket formation | Low |

| BG loop | Between αB-βG | Specificity pocket access control | Low |

Experimental Methodologies for SH2 Domain Structural and Functional Analysis

Structural Biology Approaches

X-ray crystallography has been instrumental in elucidating the atomic-level details of SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interactions. The methodology involves expressing and purifying recombinant SH2 domains, co-crystallizing them with phosphopeptide ligands, and solving the three-dimensional structure through diffraction analysis. High-resolution structures have revealed the conserved fold and specific molecular contacts governing phosphopeptide recognition, including the landmark structure of the Src SH2 domain in complex with a phosphopeptide that established the "two-pronged" binding model [10].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides complementary insights into SH2 domain structure and dynamics, particularly the internal motions and conformational fluctuations that contribute to binding specificity and affinity. NMR studies have revealed that regions distant from the binding pocket can influence specificity through allosteric mechanisms, expanding our understanding of SH2 domain function beyond static structural models [10]. Solution NMR also enables investigation of transient interactions and binding kinetics under physiological conditions.

Biophysical and Biochemical Characterization

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) provides quantitative measurements of binding affinity (Kd) and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS, n), enabling detailed characterization of the enthalpic and entropic contributions to phosphopeptide recognition. Typical SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interactions exhibit moderate affinities in the 0.1-10 μM range, balancing specificity with the reversibility required for dynamic signaling [10] [11].

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) enables real-time monitoring of binding events, providing information about association and dissociation kinetics (kon, koff). The kinetic parameters derived from SPR analysis are particularly relevant for understanding how SH2 domains achieve rapid exchange between binding partners in response to changing cellular conditions [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Resources for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Method | Application | Key Features | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 domains | Structural & biophysical studies | High-purity, isotopically labeled (NMR) | Protein expression and purification systems [13] |

| Phosphopeptide libraries | Specificity profiling | Positional scanning, diversity-oriented | SPR, ITC, crystallography screening [10] |

| Phosphospecific antibodies | Cellular localization & expression | Anti-pY (e.g., 4G10), domain-specific | Western blot, immunoprecipitation [14] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing | Functional validation in cellular context | Knockout, knockin, targeted mutation | Jurkat T cell models, phosphoproteomics [14] |

| LC-MS/MS platforms | Quantitative phosphoproteomics | TMT labeling, phosphopeptide enrichment | Pathway analysis, pY signaling networks [14] |

| Z-Phe-Arg-PNA | Z-Phe-Arg-PNA, MF:C29H33N7O6, MW:575.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Hsd17B13-IN-26 | Hsd17B13-IN-26|Potent HSD17B13 Inhibitor|RUO | Hsd17B13-IN-26 is a potent, small-molecule inhibitor of the HSD17B13 enzyme for NAFLD/NASH research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Research Directions and Therapeutic Targeting

Non-Canonical Functions and Signaling Mechanisms

Recent research has expanded our understanding of SH2 domain functions beyond traditional phosphopeptide recognition. Emerging evidence indicates that many SH2 domains interact with membrane phospholipids, particularly phosphoinositides such as PIP2 and PIP3 [11]. These interactions often involve cationic regions adjacent to the phosphotyrosine-binding pocket and play important roles in membrane recruitment and regulation of catalytic activity. For example, the PIP3-binding activity of the TNS2 SH2 domain regulates insulin receptor substrate-1 phosphorylation in insulin signaling pathways [11].

Liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) represents another frontier in SH2 domain research, with multivalent SH2 domain-mediated interactions driving the formation of intracellular condensates that enhance signaling specificity and efficiency. In T-cells, interactions between GRB2, Gads, and the LAT receptor contribute to phase-separated condensate formation that amplifies T-cell receptor signaling [11]. Similarly, in kidney podocytes, phase separation increases the membrane dwell time of N-WASP and Arp2/3 complexes, promoting actin polymerization [11].

SH2 Domains as Therapeutic Targets

The central role of SH2 domains in numerous disease-relevant signaling pathways has motivated extensive efforts to develop targeted inhibitors. Traditional approaches have focused on designing phosphopeptide mimetics that compete with natural ligands for binding to the SH2 domain, though these compounds often face challenges with cell permeability and metabolic stability [11].

Recent strategies have explored alternative targeting approaches, including:

- Allosteric inhibition targeting structurally diverse regions outside the conserved binding pocket

- Lipid-binding disruption through non-lipidic small molecules that interfere with membrane recruitment

- Protein-protein interaction inhibitors that target interfaces involved in higher-order assemblies

Notably, nonlipidic inhibitors of Syk kinase have demonstrated specific and potent inhibition of lipid-protein interactions, suggesting this approach could yield selective inhibitors for various SH2 domain-containing kinases [11]. The expanding understanding of SH2 domain structure and function continues to reveal new opportunities for therapeutic intervention in cancer, autoimmune disorders, and other diseases driven by aberrant phosphotyrosine signaling.

The characteristic αβββα fold of the SH2 domain represents a remarkable example of structural conservation coupled with functional diversification in eukaryotic evolution. The STAT SH2 domain exemplifies how variations on this conserved architectural theme enable specialized functions in transcriptional regulation through distinctive structural features including the absence of βE/βF strands and a split αB helix. The conserved molecular mechanisms of phosphotyrosine recognition—centered around the invariant ArgβB5—provide universal binding principles, while plasticity in specificity-determining regions enables diverse target selection. Ongoing research continues to reveal unexpected complexities in SH2 domain function, including roles in lipid binding, phase separation, and allosteric regulation. These emerging insights not only deepen our understanding of cellular signaling fundamentals but also open new avenues for therapeutic intervention in human diseases driven by phosphotyrosine signaling dysregulation.

Src Homology 2 (SH2) domains represent a critical class of protein interaction modules that specifically recognize and bind to phosphotyrosine (pY)-containing peptide motifs, thereby facilitating numerous signal transduction pathways in metazoan organisms [15] [11]. These domains arose approximately 600 million years ago alongside multicellular life, highlighting their fundamental importance in coordinating complex cellular communication systems [15]. Within the human proteome, approximately 110 proteins contain SH2 domains, which are broadly classifiable into two major structural and evolutionary subgroups: STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains [11]. Despite sharing a conserved core function in pY recognition, these subgroups exhibit distinct structural features that dictate their specialized biological roles, with STAT-type SH2 domains functioning primarily in signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins for nuclear signaling and gene transcription, while Src-type SH2 domains are typically found in cytoplasmic kinases and adaptor proteins that regulate membrane-proximal signaling events [15] [11] [16]. Understanding the key structural distinctions between these SH2 domain subtypes and their consequent functional implications provides crucial insights for developing targeted therapeutic interventions in diseases characterized by aberrant tyrosine kinase signaling, including cancer and immunological disorders [15] [17].

Structural Architecture: Comparative Analysis of SH2 Domain Subtypes

Conserved Core Structure and Phosphopeptide Binding Motifs

All SH2 domains share a conserved structural framework centered around a central anti-parallel β-sheet consisting of three primary strands (βB, βC, βD) flanked by two α-helices (αA and αB) in an αβββα configuration [15] [11]. This conserved architecture forms two functionally critical subpockets: the phosphate-binding (pY) pocket that recognizes and anchors the phosphotyrosine residue, and the specificity (pY+3) pocket that engages residues C-terminal to the pY, conferring selectivity for particular peptide motifs [15]. The pY pocket is formed by the αA helix, BC loop, and one face of the central β-sheet, while the pY+3 pocket is created by the opposite face of the β-sheet along with residues from the αB helix and CD and BC* loops [15]. A highly conserved arginine residue (located at position βB5) within the FLVR motif serves as a critical structural feature that directly coordinates the phosphate moiety of phosphotyrosine through salt bridge interactions in nearly all SH2 domains [11].

Distinguishing Structural Features Between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 Domains

Despite their shared core architecture, STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains diverge significantly in their C-terminal structural elements, which has profound implications for their functional specialization (Table 1).

Table 1: Key Structural Distinctions Between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 Domains

| Structural Feature | STAT-type SH2 Domains | Src-type SH2 Domains |

|---|---|---|

| C-terminal Structure | Contains additional α-helix (αB') in the evolutionary active region (EAR) [15] | Harbors β-sheets (βE and βF strands) in the C-terminal region [15] |

| β-strand Composition | Lacks βE and βF strands [11] | Contains additional βE and βF strands [11] |

| αB Helix Configuration | Split into two helices (αB and αB') [11] | Single continuous αB helix [11] |

| Loop Characteristics | Generally shorter loops, particularly in STAT proteins [11] | Typically longer loops, especially in enzymatic proteins [11] |

| Primary Functional Context | STAT protein dimerization and nuclear translocation [15] [18] | Intramolecular regulation and substrate recognition in kinases [17] [16] |

The evolutionary active region (EAR) at the C-terminus of the pY+3 pocket represents a key distinguishing structural element between these SH2 domain subtypes [15]. STAT-type SH2 domains contain an additional α-helix (αB') in this region, while Src-type domains instead feature β-sheets (βE and βF, though each strand is not always observed) [15]. Furthermore, in STAT-type SH2 domains, the αB helix is characteristically split into two separate helices, an adaptation believed to facilitate the dimerization function critical for STAT-mediated transcriptional regulation [11]. This structural disparity likely reflects the ancestral function of SH2 domain-containing proteins that predate animal multicellularity, as organisms like Dictyostelium already employed SH2 domain/phosphotyrosine signaling for transcriptional regulation [11].

Functional Implications: Signaling Mechanisms and Biological Roles

STAT-type SH2 Domains in Transcriptional Regulation

STAT-type SH2 domains play indispensable roles in the canonical JAK-STAT signaling pathway, wherein they mediate both receptor recruitment and STAT dimerization essential for nuclear translocation and gene transcription [18] [19]. In the classical activation mechanism, extracellular cytokines or growth factors bind to their cognate receptors, activating associated Janus kinases (JAKs) or intrinsic receptor tyrosine kinases that phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on receptor cytoplasmic domains [18]. Unphosphorylated STAT proteins (uSTATs) residing in the cytoplasm are then recruited to these receptor phosphotyrosine motifs via their SH2 domains [18] [19]. Once docked, STAT proteins become tyrosine-phosphorylated by JAKs on a conserved C-terminal tyrosine residue, enabling reciprocal SH2-phosphotyrosine interactions between two STAT monomers that facilitate their dimerization [18] [19]. The resultant parallel STAT dimers then translocate to the nucleus, bind specific DNA sequences (typically TTCN₃₋₄GAA motifs) in promoter regions of target genes, and activate transcription of proteins involved in proliferation, differentiation, survival, and immune responses [18].

The unique structural features of STAT-type SH2 domains are particularly adapted for this dimerization function. The split αB helix and distinctive EAR configuration create interaction surfaces that stabilize the parallel dimer configuration necessary for DNA binding [15] [11]. This specialization underscores how STAT-type SH2 domains have evolved specifically for their role as inducible transcription factors, with their structural attributes optimized for nuclear signaling rather than the membrane-proximal functions characteristic of Src-type SH2 domains.

Src-type SH2 Domains in Kinase Regulation and Substrate Recognition

Src-type SH2 domains, typified by those in Src family kinases, function primarily in intramolecular regulation and substrate recruitment within cytoplasmic signaling cascades [17] [16]. In Src kinases, the SH2 domain interacts with a phosphotyrosine motif in the C-terminal regulatory region, maintaining the kinase in an autoinhibited state through intramolecular binding that constrains the catalytic domain [16]. Upon activation, the SH2 domain engages phosphotyrosine sites on activated receptors or scaffolding proteins, recruiting the kinase to appropriate cellular locations and potentially contributing to substrate recognition [17] [16].

Recent structural studies using paramagnetic relaxation enhancement NMR combined with molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that Src tyrosine kinase can bind substrate peptides positioning residues C-terminal to the phosphoacceptor tyrosine in an orientation similar to serine/threonine kinases, unlike other tyrosine kinases that typically position substrates along the C-lobe [17]. This alternative binding mode suggests greater functional diversity in tyrosine kinase substrate recognition than previously appreciated and may have implications for developing more selective kinase inhibitors [17].

Diagram: Src Kinase Regulation Mechanism

Experimental Approaches: Methodologies for Studying SH2 Domain Structure and Function

Structural Characterization Techniques

Multiple biophysical and biochemical approaches have been employed to elucidate the structural distinctions and binding mechanisms of STAT-type versus Src-type SH2 domains (Table 2). X-ray crystallography has provided high-resolution structures of numerous SH2 domains in both free and ligand-bound states, revealing the conserved core fold and variations in auxiliary structural elements between subtypes [15] [11]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has been particularly valuable for characterizing conformational dynamics and mapping binding interfaces, with paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) measurements enabling the determination of peptide substrate orientations in solution [17]. For instance, PRE NMR combined with molecular dynamics simulations revealed that Src tyrosine kinase binds substrate peptides in an orientation similar to serine/threonine kinases, contrary to previously characterized tyrosine kinases [17].

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for SH2 Domain Characterization

| Method | Application | Key Insights | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | High-resolution structure determination of SH2 domains in free and bound states | Revealed conserved αβββα fold and structural variations between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains | [15] [11] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Analysis of dynamics, binding interfaces, and transient interactions | Identified alternative substrate binding modes in Src kinase; revealed conformational flexibility | [17] |

| Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE) | Mapping spatial relationships and binding orientations | Demonstrated Src kinase substrate binding differs from other tyrosine kinases | [17] |

| Site-directed Mutagenesis | Functional assessment of specific residues | Validated substrate recognition mechanisms; identified critical binding residues | [17] |

| Photo-crosslinking & Proteomics | Identification of transient interaction partners in living cells | Spatially resolved identification of tyrosine kinase substrates in subcellular compartments | [20] |

Advanced Methodologies for Mapping SH2 Domain Interactions in Cellular Contexts

Innovative techniques have been developed to capture the transient nature of SH2 domain-mediated interactions within living cells. A notable approach involves the genetic incorporation of the photo-cross-linking amino acid p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine (pBpa) at specific sites within SH2 domains, enabling covalent trapping of interacting proteins upon UV exposure [20]. This methodology was demonstrated using the c-Abl SH2 domain, where pBpa incorporation at position R175 (creating SH2amb2) enabled efficient photo-cross-linking to cellular phosphoproteins in a UV-dependent manner [20]. The modified SH2 domain retained phosphotyrosine-dependent binding specificity while gaining covalent trapping capability, allowing identification of transient interaction partners by mass spectrometry [20].

This approach was extended to map spatially restricted interactions by targeting modified SH2 domains to specific subcellular compartments including F-actin, mitochondria, and cellular membranes [20]. Each targeted SH2 variant captured unique sets of phosphoproteins characteristic of their subcellular localization, demonstrating the spatial organization of tyrosine phosphoproteomes and identifying compartment-specific signaling networks [20]. Such methodologies provide powerful tools for understanding how structural variations between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains contribute to their distinct functional specializations within different cellular contexts.

Diagram: SH2 Domain Phototrapping Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for SH2 Domain Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | Structural and biophysical studies; in vitro binding assays | Purified STAT3 and STAT5B SH2 domains for crystallography and binding affinity measurements [15] |

| Phosphopeptide Libraries | Mapping binding specificity and selectivity | Determination of sequence preferences for different SH2 domains [11] |

| pBpa (p-benzoyl-l-phenylalanine) | Photo-cross-linking amino acid for covalent trapping of interactions | Incorporation into c-Abl SH2 domain for in vivo phototrapping of phosphoproteins [20] |

| Orthogonal tRNA/aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase Pairs | Genetic incorporation of unnatural amino acids | Site-specific incorporation of pBpa into SH2 domains in mammalian cells [20] |

| Subcellular Targeting Sequences | Compartment-specific expression of modified SH2 domains | Targeting SH2 domains to actin cytoskeleton, membranes, or mitochondria [20] |

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins (¹âµN, ¹³C) | NMR spectroscopy studies | Backbone assignment and chemical shift perturbation mapping of SH2 domains [17] |

| Paramagnetic Probes (PROXYL) | NMR paramagnetic relaxation enhancement studies | Mapping peptide binding orientations and protein dynamics [17] |

| Mao-B-IN-32 | Mao-B-IN-32|MAO-B Inhibitor|Research Chemical | Mao-B-IN-32 is a potent and selective MAO-B inhibitor for neurodegenerative disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| BRD4 Inhibitor-30 | BRD4 Inhibitor-30, MF:C28H38N6O4, MW:522.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Pathological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Disease-Associated Mutations in SH2 Domains

Sequencing analyses of patient samples have identified SH2 domains as mutational hotspots in various diseases, with distinct pathological mechanisms between STAT-type and Src-type SH2 domains [15]. In STAT proteins, particularly STAT3 and STAT5B, SH2 domain mutations can result in either gain-of-function or loss-of-function phenotypes, depending on the specific residue affected and its structural role [15]. For instance, mutations at position S614 in the STAT3 SH2 domain have been associated with both autosomal-dominant hyper IgE syndrome (AD-HIES) when mutated to arginine (loss-of-function) and with various leukemias and lymphomas when mutated to other residues (gain-of-function), underscoring the delicate structural balance in SH2 domain function [15].

The functional impact of SH2 domain mutations stems from their effects on critical processes such as phosphopeptide binding specificity, dimerization stability, and conformational dynamics [15]. In STAT proteins, mutations frequently disrupt the precise geometry required for reciprocal SH2-phosphotyrosine interactions during dimerization, thereby altering nuclear translocation and DNA binding capabilities [15] [18]. In Src-type SH2 domains, pathological mutations often affect intramolecular interactions that maintain kinase autoinhibition or interfere with proper subcellular localization [16].

Emerging Targeting Strategies for SH2 Domain-Mediated Interactions

The central role of SH2 domains in pathological signaling has made them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention, with several strategies emerging to disrupt their function [15] [11]. Traditional approaches have focused on developing high-affinity phosphopeptide mimetics that competitively inhibit SH2 domain binding to phosphotyrosine sites on receptors or signaling partners [15]. However, the shallow, charged nature of pY-binding pockets has presented challenges for developing drug-like small molecules with sufficient affinity and bioavailability [15].

Recent strategies have expanded to target alternative sites, including the hydrophobic regions adjacent to the pY pocket and allosteric regulatory sites [11]. Additionally, the discovery that many SH2 domains interact with membrane phospholipids such as PIP₂ and PIP₃ has opened new avenues for therapeutic modulation [11]. For example, nonlipidic small molecules that inhibit Syk kinase by disrupting its membrane association through the SH2 domain have demonstrated the feasibility of targeting lipid-protein interactions for therapeutic benefit [11]. The emerging role of SH2 domain-containing proteins in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and biomolecular condensate formation also presents novel opportunities for modulating signaling pathway organization and output [11].

Understanding the distinct structural features of STAT-type versus Src-type SH2 domains will continue to inform the development of selective inhibitors that can precisely modulate specific signaling pathways while minimizing off-target effects in therapeutic applications.

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a critical modular domain that mediates protein-protein interactions in cellular signaling networks by specifically recognizing phosphorylated tyrosine residues. As a cornerstone of phosphotyrosine signaling, its function is indispensable for propagating signals downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases and other tyrosine kinases, influencing processes such as cell differentiation, proliferation, and survival. Central to this recognition is the FLVR motif, a highly conserved sequence element that houses a critical arginine residue responsible for coordinating the phosphotyrosine moiety. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of the FLVR motif and its conserved arginine, framing this discussion within the context of a broader investigation into STAT SH2 domain structure and phosphotyrosine binding mechanisms. Understanding the precise molecular details of this interaction is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to therapeutically target SH2 domain-mediated signaling pathways in diseases such as cancer.

Canonical SH2 Domain Architecture and the FLVR Motif

The SH2 domain comprises approximately 100 amino acids and adopts a conserved fold consisting of a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices [21] [2]. This structure creates two primary ligand-binding sites: a deep, positively charged pocket that binds the phosphotyrosine (pTyr) and a more shallow, variable pocket that recognizes specific amino acids C-terminal to the pTyr, typically at the +3 position [21] [22]. This "two-pronged plug" interaction ensures both high-affinity and sequence-specific binding to target peptides [21] [5].

The FLVR motif (sometimes extended as "FLVRES"), located on the βB strand, is the most characteristic and conserved feature of the pTyr-binding pocket [21] [23]. The arginine residue at the βB5 position within this motif is invariant in 117 of the 120+ human SH2 domains, underlining its fundamental role [21] [23]. In canonical SH2 domains, this arginine side chain extends into the pTyr-binding pocket, forming a direct salt bridge with the phosphate group of the bound pTyr residue [21] [2]. This interaction contributes a significant portion of the binding free energy, with point mutation of this arginine leading to a 1,000-fold reduction in binding affinity [21] [23]. Consequently, mutation of this residue is a standard experimental strategy to generate a "dead" SH2 domain and disrupt pTyr-dependent signaling [23].

Table 1: Key Structural Elements of the Canonical SH2 Domain Phosphotyrosine Binding Pocket

| Structural Element | Description | Role in pTyr Binding |

|---|---|---|

| FLVR Motif (βB strand) | Highly conserved sequence containing the βB5 arginine. | Provides the primary arginine residue for phosphate coordination; major contributor to binding energy. |

| Arg βB5 | Invariant arginine within the FLVR motif. | Forms a direct, bidentate salt bridge with the phosphate moiety of pTyr. |

| pTyrosine Pocket | Deep, basic pocket formed by αA, βB, βC, βD, and the BC loop. | Binds the phosphorylated tyrosine residue via electrostatic interactions. |

| Specificity Pocket | Shallow cleft formed by αB, βG, and the BG/EF loops. | Recognizes residues C-terminal to pTyr (e.g., +3 position), conferring binding specificity. |

| Residues αA2 & βD6 | Often basic residues (Arg/Lys) adjacent to the pocket. | Assist in pTyr coordination; define Src-like (αA2) vs. SAP-like (βD6) SH2 classes. |

Figure 1: Canonical SH2-pTyr Binding Mechanism. The SH2 domain uses two distinct pockets to engage its ligand. The phosphotyrosine is anchored via a direct salt bridge with the conserved Arg βB5 of the FLVR motif, while residues C-terminal to the pTyr (e.g., +3) bind the specificity pocket.

Diversity and Exceptions in FLVR-Mediated Binding

Despite the well-established canonical model, recent structural studies have revealed surprising diversity in FLVR motif function, illustrating that the SH2 fold is more versatile than previously appreciated.

The "FLVR-Unique" SH2 Domain of p120RasGAP

A landmark discovery challenging the canonical model is the C-terminal SH2 domain of p120RasGAP. Structural and biophysical analyses demonstrated that its FLVR arginine (R377) does not contact the bound phosphotyrosine (pTyr1087 of a p190RhoGAP peptide) [23] [24]. Instead, R377 forms an intramolecular salt bridge with a separate aspartic acid residue (D380) [23]. Strikingly, an R377A mutation did not significantly impair phosphopeptide binding. Instead, pTyr coordination is achieved through an alternative set of residues, including an unusual arginine at the βD4 position (R398) and a lysine at βD6 (K400) [23]. This novel architecture classifies the p120RasGAP C-SH2 domain as "FLVR-unique," revealing a hitherto unrecognized diversity in SH2 domain interactions.

Ancestral and Non-Metazoan SH2 Domains

Further diversity is found in evolutionarily ancient SH2 domains. The transcription elongation factor SPT6 in yeast contains tandem SH2 domains considered evolutionary precursors to metazoan SH2 domains [21] [5]. Its N-terminal SH2 domain uses the FLVR arginine to coordinate a phosphothreonine (pThr) within a pT-X-Y motif, where a tyrosine residue also occupies part of the canonical pTyr pocket [21]. This suggests an evolutionary stepping stone toward dedicated pTyr recognition. Additionally, SH2 domains in Legionella pneumophila bacteria, likely acquired via horizontal gene transfer, bind pTyr using the conserved FLVR arginine but exhibit low sequence selectivity due to the lack of a well-defined specificity pocket, instead using a large insert to "clamp" the peptide [21].

Table 2: Non-Canonical FLVR Motif Functions in Diverse SH2 Domains

| SH2 Domain | Organism / Context | FLVR Arginine Role | Key Binding Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| p120RasGAP C-SH2 | Homo sapiens ("FLVR-unique") | No pTyr contact; forms intramolecular salt bridge. | pTyr coordinated by Arg βD4 and Lys βD6. Low nanomolar affinity for pYXXP motifs. |

| SPT6 N-SH2 | Yeast (Ancestral) | Binds phosphothreonine (pThr) phosphate. | Recognizes pT-X-Y motif; Tyr occupies aromatic pocket. Evolutionary precursor to pTyr binding. |

| LeSH2 | Legionella pneumophila (Bacterial) | Canonical pTyr coordination. | Low sequence selectivity; large EF loop insert "clamps" peptide for high-affinity binding. |

| SHIP1 | Homo sapiens (Disease mutation) | Critical for domain stability, not just binding. | Aromatic F28 mutation (F28L) causes protein destabilization and proteasomal degradation. |

FLVR Motif in STAT SH2 Domains and Therapeutic Targeting

STAT SH2 Domain Specificity

STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) proteins are a key family of transcription factors activated by SH2 domain-mediated recruitment to cytokine and growth factor receptors. Following phosphorylation by JAK kinases or receptor tyrosine kinases, two STAT monomers dimerize via reciprocal SH2-pTyr interactions to form an active transcription complex [22] [11]. STAT SH2 domains belong to a distinct structural subclass that lacks the βE and βF strands and possesses a split αB helix, an adaptation believed to facilitate the specific dimerization interface [11]. The FLVR arginine in STATs is essential for this process, as it directly engages the pTyr of the opposing STAT monomer. The specificity of each STAT family member is determined by the sequence surrounding the pTyr in the receptor and the complementary specificity pocket of its SH2 domain, ensuring the appropriate cellular response to specific extracellular signals.

FLVR Motif as a Therapeutic Target

Given the pivotal role of SH2 domains in oncogenic signaling, they represent attractive therapeutic targets. Strategies often focus on developing high-affinity phosphopeptide mimetics or small molecules that occupy the pTyr-binding pocket, thereby disrupting pathogenic protein-protein interactions [11] [1]. The conserved FLVR arginine is a central feature of this pocket. However, the discovery of "FLVR-unique" domains and the critical role of the FLVR motif in maintaining overall protein stability, as seen with SHIP1 mutations, reveal additional layers of complexity for therapeutic intervention [25]. Furthermore, emerging roles for SH2 domains in binding phospholipids and participating in liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) suggest that targeting these non-canonical functions could offer novel therapeutic avenues [11].

Figure 2: STAT Activation Pathway. Cytokine signaling leads to JAK-mediated phosphorylation of STATs. Phosphorylated STATs dimerize through reciprocal interactions between one monomer's FLVR arginine (in the SH2 domain) and the other's phosphotyrosine, enabling nuclear translocation and gene regulation.

Experimental Analysis of the FLVR Motif

Key Methodologies and Protocols

Investigating the structure and function of the FLVR motif relies on a suite of biophysical and structural biology techniques.

- X-ray Crystallography: This is the primary method for determining the atomic-level structure of SH2 domains in their apo state or in complex with phosphopeptide ligands. The protocol involves recombinant expression and purification of the SH2 domain, crystallization, and structure solution. For example, the structure of the p120RasGAP C-SH2 domain (PDB: 6WAY) was solved at 1.5 Ã… resolution, revealing the unexpected "FLVR-unique" binding mechanism [23] [24].

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): ITC is used to quantitatively characterize binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS). In the p120RasGAP study, ITC was crucial for demonstrating that the R377A FLVR mutation did not abolish binding, whereas the tandem R398A/K400A mutation did [23].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: This is a fundamental approach for probing the functional contribution of specific residues. The conserved FLVR arginine is frequently mutated to alanine (R→A) to assess its necessity for pTyr binding and downstream signaling in cellular assays [21] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating the FLWR Motif and SH2 Domain Function

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | Purified protein fragments for in vitro binding assays, crystallization, and ITC. | p120RasGAP C-SH2 domain (residues 330-440) used for structural and ITC studies [23]. |

| Phosphotyrosine Peptides | Synthetic peptides corresponding to known binding motifs for affinity and specificity measurements. | p190RhoGAP phosphopeptide (DpYAEPMD) used in co-crystallization with p120RasGAP C-SH2 [23] [24]. |

| "Dead" SH2 Mutants (R→A) | Negative control to confirm phosphotyrosine-dependent interactions are mediated by the SH2 domain. | Mutation of the FLVR arginine (e.g., R377A in p120RasGAP) to generate binding-deficient domains [23]. |

| SH2 Domain Superbinder | Engineered SH2 domain with dramatically increased pTyr-binding affinity; can disrupt signaling. | A mutant SH2 used to study the consequences of sequestering pTyr motifs, demonstrating the importance of transient interactions [2]. |

| Non-lipidic Small Molecule Inhibitors | Compounds targeting lipid-binding sites or pTyr pockets on SH2 domains for therapeutic development. | Nonlipidic inhibitors of Syk kinase's SH2 domain show potential for targeted therapy [11]. |

| Flgfvgqalnallgkl-NH2 | Flgfvgqalnallgkl-NH2, MF:C80H130N20O18, MW:1660.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ac-LETD-CHO | Ac-LETD-CHO|Caspase-6/8 Inhibitor|For Research |

The Src Homology 2 (SH2) domain is a modular protein interaction domain that specifically recognizes phosphorylated tyrosine (pTyr) residues, serving as a critical component in intracellular signal transduction. While the binding of the phosphorylated tyrosine itself provides a fundamental anchor, the specificity of SH2 domain interactions is largely governed by the molecular recognition of amino acid residues located C-terminal to the pTyr. This recognition determines the precise pairing between SH2 domain-containing proteins and their targets, enabling the orchestration of complex cellular pathways. Within the context of STAT (Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription) proteins, the SH2 domain is particularly critical, mediating both receptor recruitment and the dimerization required for transcriptional activity. Understanding the structural and biophysical principles underlying this C-terminal recognition is therefore essential for elucidating normal physiology and developing targeted therapies for diseases driven by aberrant tyrosine kinase signaling, such as cancer and immunodeficiencies [15] [11].

Structural Architecture of the SH2 Domain

The SH2 domain adopts a conserved fold consisting of a central anti-parallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, forming a characteristic αβββα structure. This architecture creates two adjacent binding pockets that engage the phosphopeptide in an extended conformation [15] [26].

- pTyr-Binding Pocket: The pocket that engages the phosphotyrosine is located in the N-terminal half of the domain and is highly conserved. It features a key, invariant arginine residue at position βB5 (often within a "FLVR" motif) that forms bidentate hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety of the pTyr. This interaction contributes approximately half of the total binding free energy [11] [27] [5].

- Specificity Pocket (pY+3 Pocket): The pocket that confers binding specificity is formed by the C-terminal half of the SH2 domain, primarily by the αB helix, βG strand, and the EF and BG loops. This pocket engages residues C-terminal to the pTyr, with a particularly strong preference for the amino acid at the pY+3 position [15] [26] [28].

The following Dot language code defines the structural organization of a canonical SH2 domain and its peptide-binding mechanism.

Figure 1: SH2 Domain Structural Architecture and Phosphopeptide Binding. The canonical SH2 domain fold consists of a central β-sheet flanked by two α-helices. This structure forms two primary binding pockets: a conserved pTyr-binding pocket that engages the phosphate group via a critical arginine residue, and a variable specificity pocket that recognizes residues C-terminal to the pTyr, determining binding specificity.

Key Determinants of C-Terminal Specificity

The Primacy of the pY+3 Position

Recognition of the residue at the pY+3 position is the principal determinant of specificity for most SH2 domains. The hydrophobic nature and precise geometry of the pY+3 pocket select for specific amino acid side chains. For example, the SH2 domain of Src kinase possesses a deep hydrophobic pocket that optimally accommodates an isoleucine at the pY+3 position, as in the classic pYEEI motif [28] [27]. This interaction is so critical that single point mutations in the EF loop of the SH2 domain can radically alter specificity. A seminal study demonstrated that mutating ThrEF1 to tryptophan in the Src SH2 domain physically occluded the canonical pY+3 pocket and created a new binding surface, thereby switching its specificity to recognize an asparagine at the pY+2 position, mimicking the specificity of the Grb2 SH2 domain [28].

Contributions of pY+1 and pY+2 Positions

While the pY+3 residue is dominant, the residues at the pY+1 and pY+2 positions also contribute to binding affinity and specificity, albeit to a lesser degree. Their side chains often form hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions with residues in the BC loop and the surface of the β-sheet. The SH2 domain of SH2-B, for instance, specifically recognizes a glutamate at the pY+1 position in addition to the hydrophobic residue at pY+3 when bound to its target on Jak2 [29]. The cumulative effect of these interactions refines the selectivity beyond what is possible from the pY+3 interaction alone.

The Role of Variable Loops

The loops connecting secondary structures, particularly the EF and BG loops, are highly variable in length and composition across different SH2 domains. They act as "gates" or "filters" that control access to the specificity pocket. The conformation and chemical properties of these loops determine which peptide sequences can be accommodated and effectively engaged, thereby playing a crucial role in defining the unique binding signature of each SH2 domain [11].

STAT-Type SH2 Domains: A Case Study in Dimerization Specificity

STAT proteins feature a distinct subclass of SH2 domains that are critical for their function and exhibit unique structural adaptations. Unlike Src-type SH2 domains, STAT-type SH2 domains lack the βE and βF strands and have a split αB helix. This unique architecture is an adaptation that facilitates STAT dimerization, a critical step in their activation and nuclear translocation [15] [11].

In STAT proteins, the SH2 domain mediates a specific and reciprocal interaction: the phosphopeptide containing the pTyr from one STAT molecule is bound by the SH2 domain of another STAT partner. The specificity of this homodimerization (or, in some cases, heterodimerization) is directly controlled by the recognition of C-terminal residues in the partner's tail. This precise molecular recognition ensures that only the correct STAT isoforms dimerize, which is essential for the specific transcriptional programs they activate [15].

Mutations within the SH2 domain of STAT3 and STAT5, frequently identified in cancer and immunodeficiencies, often disrupt this delicate recognition. These mutations can be either loss-of-function or gain-of-function, sometimes even at the same residue, underscoring the evolutionary precision of the wild-type structure. For example, various somatic mutations at Ser614 and Glu616 in STAT3 are linked to lymphomas and leukemias, highlighting how altered recognition of C-terminal residues can drive pathogenesis [15].

Quantitative Analysis of Binding Energetics

The binding of SH2 domains to their cognate phosphopeptides is characterized by moderate affinity, with dissociation constants (K~d~) typically ranging from 0.1 to 10 μM. This moderate affinity is crucial for allowing transient yet specific interactions in dynamic signaling networks [26] [11]. The table below summarizes the energetic contributions of key interactions, primarily derived from alanine-scanning mutagenesis and thermodynamic studies.

Table 1: Energetic Contributions of Key Residues to SH2 Domain-Peptide Binding

| Interaction / Residue | Energetic Contribution (ΔΔG) | Functional Role | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate - Arg βB5 | ~ +3.2 kcal/mol (upon mutation) [27] | Contributes ~50% of total binding free energy; essential for pTyr docking. | Src SH2 domain alanine mutagenesis [27]. |

| pY+3 Residue (e.g., Ile) | ~ +1.0 to +2.0 kcal/mol (upon mutation) [27] | Major determinant of binding specificity; inserts into hydrophobic pocket. | Src SH2 binding to pYEEI peptide [27]. |

| pY+1 / pY+2 Residues | Generally < +1.0 kcal/mol each (upon mutation) [27] | Fine-tunes binding affinity and specificity through peripheral contacts. | Energetic analysis of Src SH2 ligands [27]. |

| Conserved His (C-SH2) | Significant (pH-dependent binding) [30] | Participates in coordinating pTyr phosphate; affects binding kinetics. | Folding and binding studies of SHP2 C-SH2 [30]. |

The table below provides examples of specific SH2 domains and their characteristic ligand preferences, illustrating how the molecular recognition of C-terminal residues translates into distinct biological functions.

Table 2: Specificity Profiles of Selected SH2 Domains

| SH2 Domain Protein | Characteristic Ligand Motif | Key C-Terminal Specificity Determinant | Biological Function / Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Src Tyrosine Kinase | pYEEI | Isoleucine at pY+3 [28] [27] | Integrin signaling, cell proliferation. |

| Grb2 Adaptor | pYVNV | Asparagine at pY+2 [28] [31] | Ras-MAPK pathway activation. |

| PLCγ C-SH2 | pYIIP | Isoleucine at pY+1, Proline at pY+3 [31] | Phosphoinositide hydrolysis, calcium signaling. |

| STAT3 | pYXXQ | Glutamine at pY+3 (in dimerization interface) [15] | STAT dimerization, nuclear translocation, gene transcription. |

| SH2-B | pY(E/D)XV | Glutamate at pY+1, hydrophobic at pY+3 [29] | Recruitment to activated Jak2 kinase. |

Experimental Methods for Profiling Specificity

Core Methodologies

Elucidating the rules of C-terminal recognition has relied on a suite of biochemical and biophysical techniques.

- Phosphopeptide Library Screening: This high-throughput approach involves screening SH2 domains against vast libraries of degenerate phosphopeptides. The bound peptides are then sequenced to derive a consensus binding motif, revealing preferences at each position C-terminal to the pTyr [26].

- Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC): ITC directly measures the heat change during binding, providing a full thermodynamic profile, including dissociation constant (K~d~), stoichiometry (n), enthalpy (ΔH), and entropy (ΔS). It is the gold standard for quantifying binding affinity and has been instrumental in mapping energetic contributions, such as the dominant role of the Arg βB5-pTyr interaction [27].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Energetic Mapping: By systematically mutating residues in either the SH2 domain or the peptide ligand to alanine and measuring the change in binding affinity (ΔΔG), researchers can create an energetic map of the interface. This "alanine-scanning" has been critical for defining the contribution of individual C-terminal residues to the overall binding energy [27].

- X-Ray Crystallography & NMR Spectroscopy: These structural techniques provide atomic-resolution snapshots of SH2 domains in complex with their phosphopeptide ligands. They visually reveal how the pockets are formed, how the peptide is oriented, and the specific atomic contacts (e.g., hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces) that define specificity [29] [28].

The following Dot language code visualizes the workflow of a comprehensive experiment to characterize SH2 domain specificity.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Profiling SH2 Domain Specificity. A multi-technique approach is used to define the molecular recognition of C-terminal residues. The process typically begins with high-throughput library screening to identify consensus motifs, followed by quantitative measurements of binding affinity and thermodynamics. Energetic mapping through mutagenesis pinpoints critical residues, while structural analysis provides atomic-level detail. These data are integrated to build a comprehensive specificity model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SH2 Domain Specificity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant SH2 Domains | Purified protein for in vitro binding and structural studies. | Expressed in E. coli or other systems for ITC, crystallography, and peptide library screens [30] [27]. |

| Synthetic Phosphopeptides | Defined ligands for binding assays and structural biology. | Peptides mimicking known or putative binding sites (e.g., from Gab2 for SHP2 studies) [30]. |

| Phosphopeptide Libraries | High-throughput profiling of binding motif preferences. | Screening with immobilized or soluble libraries to determine consensus sequences for a given SH2 domain [26]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Generation of SH2 domain mutants to probe function. | Used to create point mutants (e.g., Arg βB5 to Ala) to dissect energetic contributions [27]. |

| Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | Label-free measurement of binding affinity and thermodynamics. | Directly measuring the K~d~ of an SH2 domain for a phosphopeptide ligand in solution [27]. |

| Magl-IN-14 | Magl-IN-14, MF:C17H17F6N3O3, MW:425.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (D-Arg8)-Inotocin | (D-Arg8)-Inotocin, MF:C39H68N14O11S2, MW:973.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Therapeutic Intervention and Drug Discovery

The critical role of SH2 domains in signaling, particularly in pathologies like cancer, makes them attractive therapeutic targets. The shallow, charged nature of the pTyr-binding pocket has historically posed a challenge for small-molecule drug development. Consequently, strategies have evolved to target the adjacent specificity pocket or allosteric sites [15] [11].

- Targeting the Specificity Pocket: The pY+3 pocket, being more variable and often hydrophobic, presents a more druggable surface. Designing molecules that mimic the C-terminal residues and occupy this pocket can achieve greater specificity, potentially inhibiting pathogenic protein-protein interactions without affecting other SH2-mediated pathways [15].

- Exploiting Unique Structural Features: STAT-type SH2 domains possess unique structural elements, such as the αB' helix and distinct loop conformations, which are not found in other SH2 domains. These features represent potential targets for developing inhibitors specific to STAT3 or STAT5, aiming to disrupt their pathological dimerization in cancer [15].

- Considering Dynamics and Allostery: SH2 domains are not static; they exhibit conformational dynamics on microsecond timescales. Future drug discovery efforts must account for this flexibility. Furthermore, targeting sites distal to the binding pocket that allosterically regulate phosphopeptide binding is an emerging and promising strategy [15] [11].

The molecular recognition of residues C-terminal to phosphotyrosine is the linchpin of specificity in SH2 domain-mediated signaling. The structural and biophysical principles governing this recognition—centered on the engagement of the pY+3 residue within a variable hydrophobic pocket—enable the precise assembly of signaling complexes that drive cellular responses. STAT SH2 domains exemplify how this canonical mechanism has been specialized for the critical function of transcription factor dimerization. Continued technological advances in structural biology, biophysics, and chemical biology are steadily overcoming the historical challenges of targeting these interfaces. A deep and nuanced understanding of C-terminal recognition determinants is therefore foundational to the future development of targeted therapeutics aimed at modulating SH2 domain function in human disease.

The Two-Pronged Plug Two-Holed Socket Binding Model

The "two-pronged plug two-holed socket" model represents a foundational concept in molecular signaling for understanding how Src homology 2 (SH2) domains achieve specific recognition of phosphotyrosine (pTyr) motifs [32] [33]. This model has been instrumental in deciphering the mechanisms of intracellular communication downstream of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and has particular relevance for understanding the structure and function of STAT (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) proteins, which utilize SH2 domains for both receptor recruitment and dimerization [22] [33]. The precision of this binding mechanism enables the orchestration of diverse cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, survival, and migration [22]. This review examines the structural basis, experimental validation, and evolution of this canonical model within the broader context of STAT SH2 domain research and phosphotyrosine recognition.

The Structural Basis of the Model

Canonical SH2 Domain Architecture

SH2 domains are modular protein components of approximately 100 amino acids that adopt a conserved fold consisting of a central antiparallel β-sheet flanked by two α-helices, described as a βαββββαβ structure [2] [33]. The central β-sheet is typically composed of several strands (βA through βG) surrounded by two α-helices (αA and αB) [11] [2]. The N-terminal region of the SH2 domain, which provides the pTyr-binding pocket, is more conserved than the C-terminal half, which exhibits greater structural variability and is primarily responsible for binding specificity [2].

The "Two-Pronged Plug Two-Holed Socket" Mechanism

The binding mechanism is elegantly simple: a phosphorylated peptide ligand binds perpendicularly to the central β-strands of the SH2 domain and docks into two adjacent recognition sites [5] [33]. This creates a bidentate interaction resembling a two-pronged plug (the peptide) inserting into a two-holed socket (the SH2 domain) [32] [5].

Phosphotyrosine Binding Pocket: The first "hole" in the socket is a deep, positively charged pocket that coordinates the phosphotyrosine residue. This pocket is formed by residues from the αA helix, βB, βC, βD strands, and the BC "phosphate binding loop" [5]. A critical, highly conserved arginine residue at position βB5 (part of the FLVR motif) serves as the floor of this pocket and forms bidentate hydrogen bonds with the phosphate moiety of pTyr [22] [5] [2]. This interaction provides approximately half of the total binding free energy, with mutation of this arginine resulting in a 1,000-fold reduction in binding affinity [5].

Specificity Pocket: The second "hole" is a hydrophobic pocket that engages residues C-terminal to the phosphotyrosine, typically recognizing an amino acid at the +3 position (three residues C-terminal to pTyr) [22] [5] [33]. This pocket is formed by residues from the αB helix, βG strand, and the BG and EF loops [5]. The composition and configuration of these loops determine whether an SH2 domain has specificity for a residue at the +2, +3, or +4 position [2].

Diagram 1: Two-Pronged Plug Model of SH2-pTyr Peptide Binding

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

Key Experimental Evidence

The "two-pronged plug two-holed socket" model was initially derived from X-ray crystallographic studies of the Src SH2 domain in complex with phosphotyrosyl peptides [32] [33]. Subsequent research has utilized various biophysical techniques to validate and refine this model.

A seminal thermodynamic study by Bradshaw et al. (1998) used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to probe the binding mechanism of the Src SH2 domain to phosphotyrosyl peptides [32]. This investigation provided quantitative evidence regarding the hydrophobic basis for high-affinity binding and the role of the +3 residue insertion into the hydrophobic pocket.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: ITC Binding Assay

Objective: To determine the thermodynamic parameters of SH2 domain binding to phosphotyrosine peptides and validate the two-pronged plug model.

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation: Recombinant SH2 domain (e.g., Src SH2) is expressed in E. coli and purified using affinity chromatography (e.g., GST-tag) and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Peptide Synthesis: Phosphotyrosine-containing peptides corresponding to known binding motifs (e.g., pYEEI for Src) and control peptides with varying +3 residues (I, L, V, A) are synthesized using solid-phase peptide synthesis.

- ITC Measurements:

- The SH2 domain solution is loaded into the sample cell.

- The phosphopeptide solution is loaded into the syringe.

- A series of injections of peptide into the protein solution is performed while monitoring heat changes.

- Experiments are conducted at constant temperature with thorough stirring.

- Data Analysis:

- Integrated heat data is fitted to a single-site binding model.

- Thermodynamic parameters (ΔG°, ΔH°, ΔS°, ΔCp°) are calculated.

- Binding affinities (Kd values) are determined for different peptide sequences.

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Purified SH2 domain protein (0.1-0.5 mM in ITC buffer)

- Phosphotyrosine peptides (1-2 mM in same buffer)

- ITC Buffer: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP

- Control: Non-phosphorylated peptide to confirm phosphorylation dependence

Quantitative Binding Data

The table below summarizes typical binding affinities and thermodynamic parameters for SH2 domain-phosphopeptide interactions, demonstrating the significance of both pTyr and +3 residue interactions:

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters of SH2 Domain Binding to Phosphopeptides

| SH2 Domain | Peptide Sequence | Kd (μM) | ΔG° (kcal/mol) | ΔH° (kcal/mol) | -TΔS° (kcal/mol) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Src | pYEEI | 0.2-0.5 | -8.8 to -9.2 | -5.5 to -7.0 | -2.5 to -3.0 | [32] [2] |

| Src | pYAEI | ~1.0 | ~-8.2 | ~-4.5 | ~-3.7 | [32] |

| Grb2 | pYXNX | 0.1-1.0 | -8.1 to -8.9 | -4.0 to -5.5 | -3.2 to -3.8 | [22] [33] |

| PLC-γ | pYφXφ* | 0.5-2.0 | -7.8 to -8.4 | -5.0 to -6.5 | -2.2 to -2.7 | [22] |

*φ represents hydrophobic residues

Table 2: Effect of +3 Residue Mutations on Src SH2 Binding Affinity