Comprehensive 2D-PAGE Guide: Integrating Native and SDS-PAGE for Advanced Protein Characterization

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) that sequentially combines Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE.

Comprehensive 2D-PAGE Guide: Integrating Native and SDS-PAGE for Advanced Protein Characterization

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for implementing two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) that sequentially combines Native PAGE and SDS-PAGE. This powerful orthogonal approach enables detailed analysis of protein complexes in their native state followed by resolution of individual subunits by molecular weight. Covering foundational principles, step-by-step methodologies, troubleshooting strategies, and validation techniques, this guide addresses critical applications in studying protein-protein interactions, complex composition, and structural alterations relevant to disease mechanisms and drug target validation. The integrated protocol preserves the strengths of both techniques—maintaining native conformation and function while enabling high-resolution subunit separation—for enhanced proteomic analysis in biomedical research.

Understanding Native and SDS-PAGE: Fundamental Principles for Effective 2D Integration

Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Native PAGE) is a powerful analytical technique used to separate proteins in their native, folded state, preserving their biological activity and higher-order structure. Unlike denaturing electrophoresis methods, Native PAGE maintains protein complexes in their intact form, allowing researchers to study functional protein properties, oligomeric states, and protein-protein interactions under conditions that mimic physiological environments. This technique is particularly valuable in the context of two-dimensional PAGE research, where it serves as an essential first-dimension separation method that can be coupled with subsequent denaturing separations to provide comprehensive protein characterization.

The fundamental principle of Native PAGE relies on the fact that proteins carry a net charge at any pH other than their isoelectric point (pI), causing them to migrate through a polyacrylamide gel matrix under the influence of an electric field [1]. During this migration, separation occurs based on three key properties: the protein's intrinsic charge, its molecular size, and its three-dimensional shape [2] [3]. This multi-parameter separation mechanism makes Native PAGE uniquely suited for analyzing complex protein mixtures while maintaining structural integrity and biological function.

Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

The Tripartite Basis of Separation

The core principle of Native PAGE involves the simultaneous separation of proteins based on their size, charge, and shape, creating a sophisticated separation system that preserves native protein characteristics:

Charge-based separation: In Native PAGE, proteins migrate according to their intrinsic charge density (net charge per mass unit) [1]. The electrophoretic mobility is proportional to the protein's net charge at the running buffer pH, with higher charge density resulting in faster migration toward the oppositely charged electrode. This charge-dependent migration means that acidic proteins (with low pI) will be negatively charged in alkaline running buffers and migrate toward the anode, while basic proteins (with high pI) may require specialized buffer systems and sometimes even reversed electrode polarity [4].

Size-based separation: The polyacrylamide gel matrix acts as a molecular sieve, creating a frictional force that regulates protein movement according to size [1]. Smaller proteins encounter less resistance and migrate more quickly through the gel pores, while larger proteins face greater frictional resistance and migrate more slowly. This size-dependent separation is governed by the gel pore size, which can be optimized by adjusting the acrylamide concentration [1].

Shape-based separation: Since proteins remain in their native, folded state during Native PAGE, their three-dimensional structure significantly influences migration [5]. A compact, globular protein will migrate differently than an elongated protein of the same molecular weight due to differences in hydrodynamic drag and interaction with the gel matrix. This shape sensitivity allows Native PAGE to resolve conformational variants of the same protein.

Comparative Analysis with SDS-PAGE

Understanding Native PAGE requires comparison with its denaturing counterpart, SDS-PAGE, as these techniques serve complementary roles in protein analysis:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Native PAGE versus SDS-PAGE

| Parameter | Native PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Protein State | Native, folded structure maintained [2] [3] | Denatured, linearized polypeptides [2] [6] |

| Separation Basis | Size, charge, and shape [2] [3] | Primarily molecular weight [2] [1] |

| Detergent Usage | No SDS or other denaturing detergents [3] | SDS present to denature and uniformly charge proteins [6] |

| Sample Preparation | No heating; non-reducing conditions [3] [4] | Heating with reducing agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) [3] [6] |

| Protein Function | Biological activity retained [1] [3] | Biological activity lost [2] |

| Quaternary Structure | Maintained; multimeric complexes intact [1] | Disrupted; separates into subunits [2] |

| Temperature Conditions | Typically run at 4°C to preserve native state [3] | Typically run at room temperature [3] |

| Applications | Study of protein complexes, enzymatic activity, protein-protein interactions [2] [1] | Molecular weight determination, purity assessment, subunit composition [2] [6] |

The separation mechanism of Native PAGE can be visualized as a multi-parameter sorting process, where proteins are simultaneously discriminated by their charge properties, hydrodynamic size, and conformational characteristics.

Native PAGE Methodologies and Variations

Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

Blue Native PAGE represents a specialized variant of Native PAGE that has become instrumental for analyzing membrane protein complexes and oxidative phosphorylation systems [7]. Developed by Hermann Schägger in the 1990s, BN-PAGE employs the anionic dye Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, which binds to hydrophobic protein surfaces and imposes a negative charge shift [7]. This binding forces even basic proteins with hydrophobic domains to migrate toward the anode at neutral pH and prevents aggregation of hydrophobic proteins during electrophoresis [7]. The technique is particularly valuable for studying protein assembly pathways, composition of higher-order complexes, and pathological mechanisms in genetic disorders [7].

Key characteristics of BN-PAGE include:

- Use of mild, nonionic detergents like n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside for membrane protein solubilization without dissociating complexes [7]

- Addition of zwitterionic salts such as 6-aminocaproic acid to support extraction without affecting electrophoresis [7]

- Maintenance of enzymatic activity following separation, enabling downstream activity assays [7]

- Compatibility with second-dimension SDS-PAGE for comprehensive complex analysis [7] [8]

Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE)

Clear Native PAGE is a related technique that replaces the Coomassie blue dye with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents in the cathode buffer [7] [9]. These mixed micelles induce a charge shift to enhance membrane protein solubility and migration toward the anode, similar to the Coomassie dye in BN-PAGE [7]. A key advantage of CN-PAGE is the absence of residual blue dye interference during downstream in-gel enzyme activity staining, allowing more sensitive detection of enzymatic activities [7]. However, CN-PAGE generally offers lower resolution compared to BN-PAGE but can detect enzymatically active oligomeric states that might be missed by BN-PAGE [9].

Technical Considerations for Method Selection

The choice between Native PAGE variants depends on specific research goals and sample characteristics:

Table 2: Native PAGE Method Selection Guide

| Method | Optimal Applications | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Native PAGE | Separation of soluble proteins; charge and size heterogeneity analysis [1] [4] | Preserves native function; no dye interference | Limited for membrane proteins; potential aggregation |

| Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) | Membrane protein complexes; OXPHOS systems; protein assembly studies [7] | High resolution; prevents aggregation; maintains activity | Coomassie dye may interfere with some activity assays |

| Clear Native PAGE (CN-PAGE) | Enzyme activity studies; detection of labile complexes [7] [9] | No dye interference; sensitive activity detection | Generally lower resolution than BN-PAGE |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Reagent Preparation and Gel Formulation

Successful Native PAGE requires careful preparation of specific reagents and optimization of gel compositions:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Native PAGE

| Reagent | Composition/Preparation | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-Bis Solution | 40% Acr-Bis (Acr:Bis=19:1) [4] | Gel matrix formation; pore size determination |

| Separating Gel Buffer | 1.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8 [4] | Creates high-pH environment for separation |

| Stacking Gel Buffer | 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8 [4] | Creates neutral pH for sample stacking |

| Electrophoresis Buffer | 25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, pH 8.3 [4] | Conducting medium for electrophoresis |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 10% solution in water [4] | Free radical initiator for polymerization |

| TEMED | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine [4] | Polymerization catalyst |

| Sample Buffer | 50% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue [4] | Increases density for well loading; tracking dye |

Gel Casting and Electrophoresis Procedure

The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for Native PAGE analysis of acidic proteins:

Gel Preparation:

- Assemble glass plates in casting stand, ensuring tight seal to prevent leakage [4].

- Prepare separating gel mixture according to Table 4, adding APS and TEMED last to initiate polymerization [4].

- Pour separating gel immediately after adding catalysts, leaving space for stacking gel [4].

- Overlay with isopropanol or water to create a flat interface and exclude oxygen [4].

- After polymerization (∼30 minutes), remove overlay, rinse with distilled water, and remove excess moisture [4].

- Prepare stacking gel mixture (Table 4), add catalysts, and pour over polymerized separating gel [4].

- Insert sample comb carefully, avoiding bubble formation, and allow to polymerize completely [4].

Table 4: Native PAGE Gel Compositions for Acidic Protein Separation

| Component | Separating Gel (17%) | Stacking Gel (4%) |

|---|---|---|

| 40% Acr-Bis Solution | 4.25 mL [4] | 0.5 mL [4] |

| 4× Separating Gel Buffer | 2.5 mL [4] | - |

| 4× Stacking Gel Buffer | - | 1.25 mL [4] |

| Deionized Water | 3.2 mL [4] | 3.2 mL [4] |

| 10% APS | 35 μL [4] | 35 μL [4] |

| TEMED | 15 μL [4] | 15 μL [4] |

| Total Volume | 10 mL | 5 mL |

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis:

- Prepare protein samples by mixing with native sample buffer (avoiding denaturing agents) [4]. For BN-PAGE, add Coomassie blue G-250 to samples prior to loading [7].

- Load samples into wells using micropipette, avoiding cross-contamination between lanes [4].

- Assemble electrophoresis apparatus and fill chambers with appropriate running buffer [4]. For BN-PAGE, include Coomassie dye in the cathode buffer [7].

- Run electrophoresis at constant voltage: 100 V until samples enter separating gel, then increase to 160 V until tracking dye approaches gel bottom [4]. Maintain temperature at 4°C throughout to preserve native protein structure [3].

- Terminate electrophoresis when bromophenol blue tracking dye is approximately 1 cm from gel bottom [4].

Post-Electrophoresis Analysis

Following separation, multiple detection and analysis methods can be employed:

- Activity staining: For enzymatic proteins, specific substrate-based staining can detect functional proteins in the gel [7].

- Western blotting: Proteins can be transferred to membranes for immunodetection with specific antibodies [7].

- Protein recovery: Native proteins can be recovered from gels by passive diffusion or electroelution for further studies [1].

- Coomassie or silver staining: Standard protein staining techniques visualize total protein patterns [4].

Integration in Two-Dimensional PAGE Research

Two-Dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE Methodology

The combination of Native PAGE with SDS-PAGE in a two-dimensional approach provides powerful comprehensive protein characterization. In this technique, Native PAGE (typically BN-PAGE) serves as the first dimension to separate protein complexes according to their native size and charge, followed by denaturing SDS-PAGE in the second dimension to resolve individual subunits [7] [8].

The workflow for two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE involves:

- First-dimension separation using BN-PAGE to resolve native protein complexes [7] [8].

- Excise individual lanes from the BN-PAGE gel and incubate in SDS-containing buffer to denature proteins [7].

- Place lane horizontally on top of an SDS-PAGE gel for second-dimension separation [8].

- Perform SDS-PAGE to separate subunits by molecular weight [7] [8].

- Visualize results using staining, western blotting, or mass spectrometry analysis [7].

This approach has been successfully applied to analyze snake venom proteins, revealing native complexes of metalloproteinases and serine proteinases that maintain enzymatic activity after separation [8].

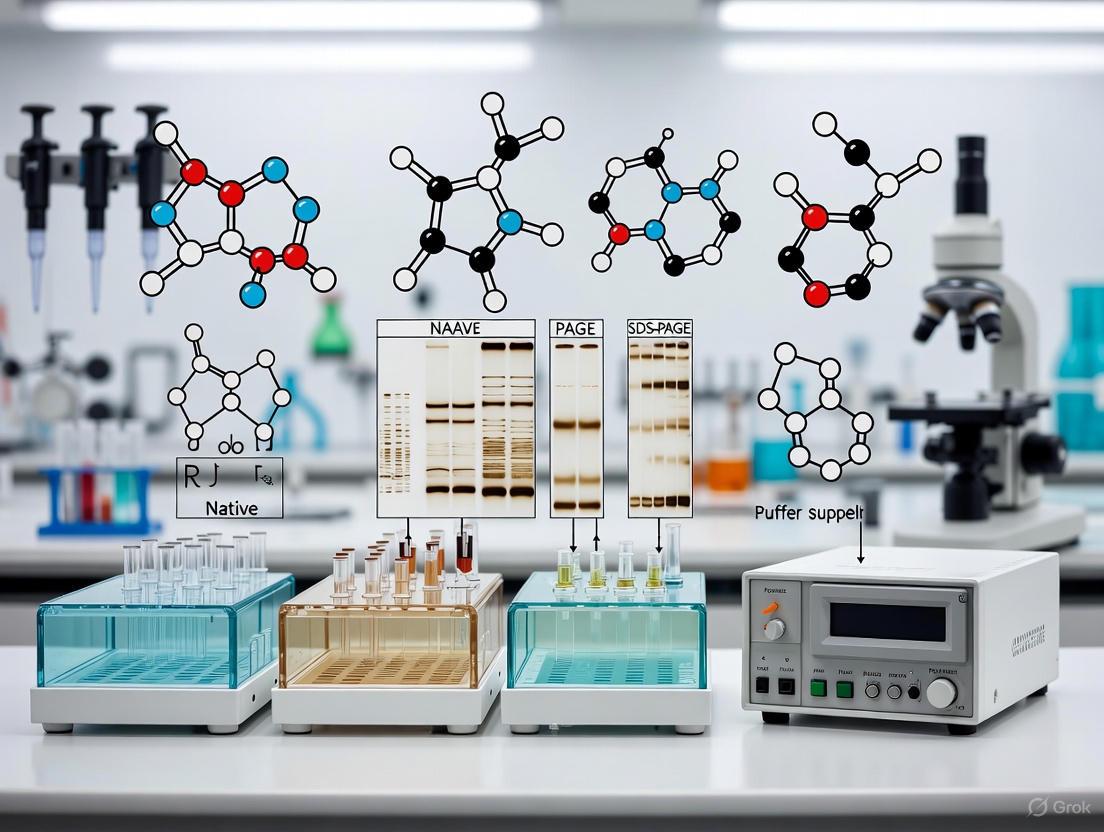

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for two-dimensional PAGE analysis integrating native and denaturing separation methods:

Critical Technical Considerations and Troubleshooting

Optimization Strategies

Successful implementation of Native PAGE requires attention to several critical parameters:

Buffer System Selection:

- For acidic proteins (pI < 7): Use high-pH buffer systems (e.g., Tris-glycine, pH 8.8) where proteins carry net negative charge and migrate toward anode [4].

- For basic proteins (pI > 7): Use low-pH buffer systems where proteins carry net positive charge; may require cathode-anode reversal [4].

- Consider alternative buffering systems like bis-tris or imidazole for specific applications [7].

Temperature Control:

- Maintain electrophoresis apparatus at 4°C to minimize protein denaturation and proteolysis [3] [4].

- Pre-cool buffers before use to ensure consistent temperature throughout separation [4].

Gel Composition Optimization:

- Lower percentage gels (4-10%) for high molecular weight complexes [1].

- Higher percentage gels (12-20%) for lower molecular weight proteins [1].

- Gradient gels (e.g., 4-16%) to resolve broad molecular weight ranges [1] [7].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Table 5: Native PAGE Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Resolution | Incorrect gel percentage; inappropriate buffer pH; excessive heating | Optimize gel density for target protein size; verify buffer pH; improve cooling [4] |

| Protein Aggregation | Insufficient solubilization; inappropriate detergent | Add compatible detergents (e.g., n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside); use BN-PAGE format [7] |

| Loss of Activity | Denaturation during separation; proteolysis | Maintain temperature at 4°C; include protease inhibitors; shorten run time [4] |

| Abnormal Migration | Incorrect buffer system for protein pI; electrode polarity issues | Verify protein pI and buffer compatibility; reverse polarity for basic proteins [4] |

| Weak Staining | Insufficient protein loading; inappropriate detection method | Increase sample amount; use sensitive detection (silver staining, fluorescence) [4] |

Research Applications and Case Studies

Application in Mitochondrial Research

Native PAGE, particularly BN-PAGE, has become indispensable in mitochondrial research for analyzing the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system [7]. This system comprises five multi-subunit complexes located in the mitochondrial inner membrane, and BN-PAGE enables researchers to:

- Resolve individual OXPHOS complexes in their native state [7]

- Study assembly pathways of these complexes [7]

- Analyze composition of respiratory chain supercomplexes (respirasomes) [7]

- Investigate pathological mechanisms in patients with monogenetic OXPHOS disorders [7]

Recent research has demonstrated the detection of dynamic alterations in OXPHOS complexes in various disease states, including neurodegenerative disorders and mitochondrial encephalomyopathies [7] [9].

Venom Protein Complex Analysis

The application of two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE has proven valuable in toxin research, particularly in analyzing snake venom compositions [8]. Research on Bothrops snake venoms has revealed:

- Presence of native protein complexes containing snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs) and snake venom serine proteinases (SVSPs) [8]

- Maintenance of enzymatic activity following BN/SDS-PAGE separation [8]

- Identification of C-type lectin-like proteins via western blotting [8]

- Preservation of biological activities enabling functional studies of venom components [8]

This application demonstrates how Native PAGE facilitates the study of protein interactions in complex biological mixtures while maintaining functional properties.

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

Native PAGE serves as a crucial tool for investigating protein-protein interactions and quaternary structure by:

- Preserving non-covalent interactions between protein subunits [1]

- Enabling determination of native molecular weights and oligomeric states [8]

- Providing insights into assembly pathways of multi-subunit complexes [7]

- Allowing identification of interacting partners in protein networks [8]

These applications highlight the unique capability of Native PAGE to maintain structural integrity while providing analytical separation of complex protein mixtures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 6: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Native PAGE

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Concentration | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide-Bis Solution | 30-40% stock (19:1 to 37.5:1 ratio) [4] | Forms porous gel matrix for molecular sieving |

| Tris-HCl Buffers | 0.5-1.5 M, pH 6.8 (stacking) and 8.8 (separating) [4] | Creates pH discontinuities for efficient stacking and separation |

| Glycine | Electrode buffer component (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine) [4] | Leading ion in discontinuous buffer system |

| TEMED | N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine [4] | Catalyzes free-radical polymerization of acrylamide |

| Ammonium Persulfate (APS) | 10% (w/v) fresh aqueous solution [4] | Free radical initiator for gel polymerization |

| Coomassie G-250 | 0.02-0.1% in cathode buffer (BN-PAGE) [7] | Imparts charge shift and prevents protein aggregation |

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltoside | 1-2% for membrane protein solubilization [7] | Mild nonionic detergent for extracting membrane complexes |

| Glycerol | 10-50% in sample buffer [4] | Increases sample density for well loading |

| Protease Inhibitors | Cocktail tablets or solutions [4] | Prevents protein degradation during separation |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Native protein standards [1] | Calibrates molecular size estimation under native conditions |

| Dehydrocrenatidine | `Dehydrocrenatidine|Research Compound` | Dehydrocrenatidine is a beta-carboline alkaloid for cancer research. It induces apoptosis in studied cell lines. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Delavirdine Mesylate | Delavirdine Mesylate, CAS:147221-93-0, MF:C23H32N6O6S2, MW:552.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) represents a foundational methodology in biochemical research for separating proteins based on their molecular weight. First developed in the 1970s with key contributions from Ulrich Laemmli, this technique has become an indispensable tool for protein analysis due to its simplicity, reliability, and requirement for only microgram quantities of protein [10]. The method fundamentally relies on the denaturing action of SDS, an anionic detergent that masks proteins' intrinsic charges and unfolds their native structures, creating linear polypeptides with uniform charge-to-mass ratios [10] [1]. When subjected to an electric field within a polyacrylamide gel matrix, these SDS-protein complexes migrate strictly according to polypeptide chain length, with smaller proteins moving more rapidly through the porous network [11]. This robust separation principle makes SDS-PAGE invaluable for numerous applications including protein purity assessment, molecular weight determination, and sample preparation for downstream techniques like western blotting and mass spectrometry [12] [10].

In the context of two-dimensional electrophoresis, SDS-PAGE serves as a powerful second-dimension separation method when combined with first-dimension techniques that separate by native charge, such as blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) or isoelectric focusing [13] [8]. This integrated approach allows researchers to gain comprehensive information about complex protein samples, preserving native protein interactions in the first dimension while achieving high-resolution separation by molecular weight in the second [8] [14]. The following sections detail the core principles, standardized protocols, and practical applications of SDS-PAGE within this multidimensional analytical framework.

Core Principles of SDS-PAGE

The Role of SDS in Protein Denaturation and Linearization

The resolving power of SDS-PAGE stems primarily from the action of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), which systematically dismantles protein higher-order structure. SDS molecules possess a hydrophobic hydrocarbon chain and a hydrophilic sulfate group, enabling them to interact with both nonpolar and polar protein regions [10]. When proteins are heated to 70-100°C in buffer containing excess SDS and reducing agents like dithiothreitol (DTT) or beta-mercaptoethanol, several transformative events occur simultaneously: disulfide bonds are reduced, secondary and tertiary structures unfold, and SDS molecules bind to the polypeptide backbone in a constant weight ratio of approximately 1.4 g SDS per 1.0 g of protein [10] [1] [15].

This uniform SDS coating confers two critical properties essential for molecular weight-based separation. First, the intrinsic charge of individual amino acid residues becomes insignificant compared to the substantial negative charge provided by the bound detergent molecules. Second, the proteins adopt an extended rod-like conformation as SDS molecules associate along the polypeptide chain, effectively eliminating the influence of native protein shape on electrophoretic mobility [10] [15]. Consequently, all SDS-polypeptide complexes assume similar charge densities and geometries, creating the fundamental condition for separation based primarily on molecular size rather than charge or structural features.

Polyacrylamide Gel as a Molecular Sieve

The polyacrylamide gel matrix serves as a molecular sieve that regulates protein migration during electrophoresis. Formed through the copolymerization of acrylamide and bisacrylamide (N,N'-methylenediacrylamide) cross-linker, this network creates pores whose sizes are inversely related to the total acrylamide concentration [11] [1]. The polymerization reaction is catalyzed by ammonium persulfate (APS) and tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), with the bisacrylamide-to-acrylamide ratio and total concentration determining the gel's mechanical properties and sieving characteristics [1].

Table 1: Recommended Polyacrylamide Concentrations for Protein Separation

| Gel Percentage | Effective Separation Range | Pore Size | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-8% | 50-200 kDa | Large | High molecular weight proteins |

| 10% | 15-100 kDa | Medium | Standard protein mixtures |

| 12-15% | 5-60 kDa | Small | Low molecular weight proteins |

| 4-20% gradient | 10-300 kDa | Variable | Broad range separation |

Lower percentage gels (e.g., 6-8%) feature larger pores that facilitate the migration of high molecular weight proteins, while higher percentage gels (e.g., 12-15%) with smaller pores provide better resolution for lower molecular weight species [10] [1]. Gradient gels, which contain an increasing acrylamide concentration from top to bottom, offer extended separation ranges by creating a pore size gradient that progressively restricts the movement of proteins as they migrate [10]. This configuration allows proteins to encounter increasingly restrictive pores, sharpening bands and improving resolution across a broad molecular weight spectrum.

Discontinuous Buffer System and Stacking Effect

Standard SDS-PAGE employs a discontinuous buffer system that significantly enhances separation resolution through a stacking mechanism. This system incorporates two distinct gel regions with different compositions and pH values: a stacking gel (typically 4-5% acrylamide, pH ~6.8) layered above a resolving gel (varying percentages, pH ~8.8) [11] [1]. When current is applied, the differing mobilities of chloride ions (from the gel buffers) and glycine ions (from the running buffer) create a sharp boundary that concentrates protein samples into extremely narrow zones before they enter the resolving gel [11]. This stacking effect ensures proteins simultaneously reach the resolving region, dramatically improving band sharpness and resolution compared to continuous buffer systems.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and separation mechanism of SDS-PAGE:

SDS-PAGE in Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

Integration with Native Separation Techniques

Two-dimensional electrophoresis combining native PAGE with subsequent SDS-PAGE provides a powerful platform for analyzing protein interactions within complex mixtures. In this approach, the first dimension (native PAGE) separates protein complexes based on their intrinsic charge, size, and shape under non-denaturing conditions, preserving functional properties and protein-protein interactions [13] [1]. The second dimension (SDS-PAGE) then resolves these complexes into their constituent subunits under denaturing conditions, providing molecular weight information while maintaining the separation achieved in the first dimension [13] [8].

This native/SDS 2D system enables researchers to detect protein interactions by observing mobility shifts on the resulting 2D maps. Proteins involved in complexes will migrate at abnormal positions compared to their unbound states, allowing identification of interacting partners even in complicated protein extracts [13]. For example, this methodology has been successfully employed to study the interaction between interleukin-2 and its receptor α chain within E. coli protein extract, demonstrating its utility for characterizing specific protein-protein interactions amid numerous contaminating proteins [13].

Blue Native/SDS-PAGE for Protein Complex Analysis

Blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE) has emerged as a particularly effective first-dimension separation method for analyzing membrane protein complexes and oxidative phosphorylation systems [8] [16]. In BN-PAGE, the anionic dye Coomassie Blue G-250 binds to protein surfaces, imparting negative charge without causing significant denaturation [8] [16]. This charge shift enables protein complexes to migrate toward the anode while maintaining their native oligomeric states and enzymatic activities [12] [8].

When combined with second-dimension SDS-PAGE, this 2D BN/SDS-PAGE approach provides exceptional resolution of multiprotein complexes. The technique has been successfully applied to characterize protein interactions in Bothrops snake venoms, identifying functional complexes of snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs) and serine proteinases that retain enzymatic activity after electrophoresis [8]. Similarly, 2D BN/SDS-PAGE has revealed distinct heat shock protein complexes in HepG2.2.15 cells that support hepatitis B virus replication, highlighting the method's utility for investigating host-virus interactions [14].

The workflow below illustrates the typical procedure for two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE analysis:

Table 2: Comparison of Electrophoresis Techniques for Proteomic Analysis

| Parameter | SDS-PAGE | BN-PAGE | Native-PAGE | 2D BN/SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Molecular weight | Size and shape of complexes | Charge, size, and shape | Native state (1D) + MW (2D) |

| Protein State | Denatured and linearized | Native, functional complexes | Native conformation | Native then denatured |

| Resolution | High for polypeptides | High for protein complexes | Moderate for native proteins | Very high for complex mixtures |

| Functional Assays | Not possible | Enzymatic activity retained | Enzymatic activity retained | Activity after 1D, MW after 2D |

| Metal Retention | Minimal (26% Zn²⺠retained) | High metal retention | High metal retention | Dependent on first dimension |

| Typical Applications | MW determination, purity check | Protein interaction studies | Native charge analysis | Comprehensive complex analysis |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard SDS-PAGE Protocol

Sample Preparation

- Denaturation: Mix protein samples with SDS-PAGE sample buffer (typically containing 2% SDS, 50-100 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) with or without reducing agents [11] [10]. For reduced conditions, add 1-5% beta-mercaptoethanol or 50-100 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) to break disulfide bonds [15].

- Heating: Heat samples at 70-100°C for 3-10 minutes in a heat block to ensure complete denaturation [11] [10]. Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 1 minute to collect condensate before loading [11].

- Protein Load: Recommended protein amounts range from 0.5-25 μg per lane for Coomassie staining and 0.1-1 μg for silver staining, depending on gel thickness and complexity of the protein mixture [12] [11].

Gel Preparation and Electrophoresis

- Gel Casting: Assemble clean glass plates with spacers (typically 1.0-1.5 mm thick). Prepare resolving gel solution with desired acrylamide percentage (see Table 1), 0.1% SDS, 375 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), and polymerization catalysts (0.05% APS and 0.1% TEMED) [11] [1]. Pour the solution, overlay with water-saturated butanol or water to ensure even polymerization, and allow to set for 20-30 minutes.

- Stacking Gel: After removing the overlay, pour stacking gel solution (4-5% acrylamide, 0.1% SDS, 125 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, APS, and TEMED) and insert combs to create wells. Allow to polymerize for 15-20 minutes [11] [1].

- Electrophoresis: Mount gel cassette in electrophoresis apparatus filled with running buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3). Load samples and molecular weight markers in wells. Run at constant voltage (100-150 V for mini-gels) until dye front reaches bottom (~45-60 minutes) [11] [10].

Protein Detection and Analysis

- Staining: Following electrophoresis, carefully separate glass plates and remove gel. Stain with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (0.1% Coomassie R-250 or G-250 in 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid) for 30-60 minutes with gentle agitation [10]. Destain with multiple changes of 40% methanol, 10% acetic acid until background is clear and bands are visible.

- Alternative Stains: For higher sensitivity, use silver staining (detection limit 0.1-1 ng) or fluorescent stains compatible with mass spectrometry [10].

- Molecular Weight Determination: Compare migration distances of unknown proteins to a standard curve generated from molecular weight markers run on the same gel [10] [1].

Two-Dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE Protocol

First Dimension: BN-PAGE

- Sample Preparation: Solubilize protein complexes in native extraction buffer (25 mM BisTris-HCl pH 7.0, 20% glycerol, 0.5-2% mild detergent such as dodecyl maltoside or digitonin) supplemented with protease inhibitors [8] [16]. Incubate on ice for 30-60 minutes, then clarify by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C [14].

- BN-PAGE Conditions: Prepare native gradient gels (4-13% acrylamide) with 4% stacking gel. Add Coomassie Blue G-250 (0.01-0.02%) to both samples and cathode buffer [8] [16]. Load 50-100 μg protein per lane and run at constant voltage (100 V for 1-2 hours, then 200-250 V for 3-4 hours) at 4°C until dye front migrates to bottom [8] [14].

Second Dimension: SDS-PAGE

- Lane Excision and Equilibration: Carefully excise entire lanes from BN-PAGE gel and equilibrate in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (1% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 1% beta-mercaptoethanol) for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle agitation [8] [14].

- Second Dimension Setup: Place equilibrated gel strips horizontally on top of SDS-polyacrylamide gels (typically 10-12%) and secure with 0.5-1% agarose in SDS running buffer [8] [14].

- Electrophoresis and Analysis: Run second dimension at standard SDS-PAGE conditions. Process gels for protein detection using preferred staining method or western blotting for specific protein identification [8] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for SDS-PAGE and Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | SDS, Dodecyl Maltoside, Digitonin | Denature proteins (SDS) or gently solubilize complexes (native PAGE) |

| Reducing Agents | DTT, Beta-mercaptoethanol | Break disulfide bonds to ensure complete unfolding |

| Gel Components | Acrylamide, Bis-acrylamide | Form porous polyacrylamide matrix for molecular sieving |

| Polymerization Catalysts | APS, TEMED | Initiate and catalyze acrylamide polymerization |

| Buffer Systems | Tris-Glycine, BisTris, Tricine | Maintain pH and provide conducting ions during electrophoresis |

| Tracking Dyes | Bromophenol Blue, Phenol Red | Visualize migration progress during electrophoresis |

| Staining Reagents | Coomassie Blue, Silver Nitrate, SYPRO Ruby | Visualize separated protein bands with varying sensitivity |

| Molecular Weight Markers | Prestained/Unstained Standards | Provide reference for molecular weight determination |

| Specialized Dyes | Coomassie Blue G-250 (BN-PAGE) | Impart charge shift while maintaining native state (BN-PAGE) |

| Deltazinone 1 | Deltazinone 1, MF:C27H31N5O2, MW:457.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Demethoxyviridiol | Demethoxyviridiol, CAS:56617-66-4, MF:C19H16O5, MW:324.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Considerations and Advanced Applications

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Resolution

Successful SDS-PAGE separation requires careful optimization of multiple parameters. Gel percentage should be matched to the molecular weight range of target proteins, with gradient gels offering the broadest separation spectrum [10]. Voltage and run time must be balanced to prevent band distortion and overheating; standard conditions for mini-gels range from 100-150 V for 40-60 minutes [10]. Incomplete protein separation often results from insufficient run time, incorrect acrylamide concentration, or improper buffer preparation, while smiling or frowning bands typically indicate uneven heating or current distribution [10].

For two-dimensional applications, the choice of detergent in first-dimension BN-PAGE critically determines which complexes remain intact. Digitonin preserves weaker protein interactions and supercomplexes, while dodecyl maltoside provides more complete solubilization of individual complexes [16]. The inclusion of 6-aminocaproic acid in extraction buffers helps maintain protein solubility without interfering with electrophoresis [16].

Limitations and Alternative Approaches

While SDS-PAGE provides exceptional resolution for denatured proteins, its fundamental limitation lies in the destruction of native protein structure and function. The method strips away non-covalently bound cofactors, with one study demonstrating only 26% retention of Zn²⺠ions under standard conditions compared to 98% with modified native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) that omits EDTA and reduces SDS concentration [12]. Similarly, enzymatic activity is typically abolished, with only 2 of 9 model enzymes remaining active after standard SDS-PAGE compared to 7 of 9 with NSDS-PAGE and all 9 with BN-PAGE [12].

These limitations have spurred the development of complementary techniques. Clear native PAGE (CN-PAGE) replaces Coomassie dye with mixtures of anionic and neutral detergents, eliminating dye interference during downstream in-gel enzyme activity staining [16]. For extremely complex protein mixtures, two-dimensional electrophoresis combining isoelectric focusing (IEF) with SDS-PAGE provides the highest resolution, separating thousands of proteins based on both isoelectric point and molecular weight [1] [17]. Advanced mass spectrometry-compatible staining methods further enhance the utility of SDS-PAGE in proteomic workflows, enabling precise protein identification and characterization [17] [15].

SDS-PAGE remains an indispensable tool in modern biochemical research, providing robust molecular weight-based separation of proteins under denaturing conditions. Its integration into two-dimensional electrophoretic platforms, particularly with native separation techniques like BN-PAGE, dramatically expands analytical capabilities for studying protein complexes and interactions. The standardized protocols, well-characterized reagents, and extensive literature support make these methods accessible to researchers across diverse disciplines. As proteomic research continues to advance, the fundamental principles of SDS-PAGE will undoubtedly continue to support new developments in protein analysis, from basic characterization to sophisticated studies of complex biological systems.

The strategic choice between preserving a protein's native structure or completely denaturing it is fundamental to the success of any separation experiment. This decision dictates the type of information that can be obtained, from basic molecular weight determination to the analysis of functional complexes and biological activity [1] [5]. Denaturing methods, primarily Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), are invaluable for determining protein purity, expression levels, and covalent structural features like polypeptide molecular mass [12] [1]. However, they destroy higher-order structure and function by disrupting non-covalent interactions and disulfide bonds [12].

In contrast, native electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) separates proteins based on their intrinsic charge, size, and three-dimensional shape, maintaining quaternary structure, enzymatic activity, and bound cofactors, including metal ions [12] [1]. A significant advancement is the development of two-dimensional (2D) methods that combine these techniques, such as native PAGE in the first dimension followed by SDS-PAGE in the second, allowing for the sophisticated analysis of protein complexes and interactions within intricate biological mixtures [13] [14] [8].

This application note provides a comparative analysis of these separation philosophies, supported by quantitative data and detailed protocols for their application in modern proteomic research.

Comparative Methodologies: Principles and Outcomes

The core distinction between denaturing and native separation lies in the treatment of the protein sample prior to and during electrophoresis. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each major method.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Protein Separation Methods

| Feature | SDS-PAGE (Denaturing) | Native-PAGE | Blue Native (BN)-PAGE | NSDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separation Basis | Polypeptide molecular mass [1] | Net charge, size, & shape of native structure [1] | Size and oligomeric state of native complexes [8] | Molecular mass, with partial structural retention [12] |

| Sample Treatment | Heated with SDS and reducing agent (e.g., DTT) [1] [5] | No denaturants; non-denaturing buffer [1] | Solubilized with mild detergents; Coomassie G-250 dye [14] [8] | No heating; reduced SDS and no EDTA [12] |

| Structural Impact | Denatures; destroys quaternary structure & function [12] [1] | Preserves quaternary structure & oligomeric state [1] | Preserves native protein complexes [14] [8] | Retains some metal ions and enzymatic activity [12] |

| Functional Outcome | Loss of enzymatic activity [12] | Retention of enzymatic activity [1] | Retention of enzymatic activity [8] | Retention of enzymatic activity for most enzymes [12] |

| Primary Applications | Molecular weight estimation, purity assessment, western blotting [12] [1] | Analysis of native charge, oligomeric state, functional assays [1] | Analysis of protein-protein interactions and multiprotein complexes [12] [14] | High-resolution separation with retention of metal cofactors [12] |

The quantitative impact of the chosen method on functional preservation is stark, as demonstrated by a study on metalloproteins. The modified Native SDS-PAGE (NSDS-PAGE) method showed a dramatic increase in the retention of bound Zn²⺠compared to standard SDS-PAGE, alongside the preservation of enzymatic activity [12].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Metal Retention and Enzyme Activity

| Electrophoretic Method | Zn²⺠Retention in Proteomic Samples | Enzyme Activity Retention (Model Zn²⺠Proteins) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard SDS-PAGE | 26% | 0 out of 4 active [12] |

| BN-PAGE | Not Reported | 9 out of 9 active [12] |

| NSDS-PAGE | 98% | 7 out of 9 active [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Denaturing SDS-PAGE

This protocol is adapted for a precast NuPAGE Novex 12% Bis-Tris 1.0 mm mini-gel system [12].

Sample Preparation:

- Mix 7.5 µL of protein sample (5-25 µg protein) with 2.5 µL of 4X LDS sample loading buffer (e.g., Invitrogen).

- Heat the mixture at 70°C for 10 minutes to denature the proteins [12].

Gel Electrophoresis:

- Load the denatured samples into the wells of the precast gel. Include an appropriate molecular weight marker in one well.

- Fill the electrophoresis tank with 1X MOPS SDS running buffer (e.g., 50 mM MOPS, 50 mM Tris Base, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.7) [12].

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 200V for approximately 45 minutes, or until the dye front reaches the bottom of the gel [12].

Protocol 2: Two-Dimensional Blue Native/SDS-PAGE

This protocol is used for the analysis of intact protein complexes and their subunits, as applied in the study of snake venoms and mitochondrial complexes [14] [8] [18].

First Dimension: Blue Native PAGE (BN-PAGE)

- Sample Preparation: Solubilize proteins (e.g., 80 µg of mitochondrial or whole cell lysate) in a native buffer such as 25BTH20G (25 mM BisTris-HCl, 20% glycerol, pH 7.0) supplemented with 2% dodecyl maltoside and protease inhibitors. Incubate on ice for 40 minutes, then centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C to remove insoluble material [14].

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a native gradient gel (e.g., 4-16% or 5-13.5% acrylamide) with a 4% stacking gel [14] [8].

- Loading and Running: Combine the supernatant with BN sample buffer (e.g., 1× BisTrisACA, 30% glycerol, 5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250) and load onto the gel. Use a chilled cathode buffer (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM BisTris, 0.01% Coomassie G-250) and anode buffer (50 mM BisTris-HCl, pH 7.0). Perform electrophoresis overnight at 10°C and constant voltage (e.g., 150V) [14].

Second Dimension: Denaturing SDS-PAGE

- Gel Strip Equilibration: After the first dimension run, excise the lane of interest from the BN-PAGE gel. Equilibrate the gel strip for 30 minutes in 1X SDS loading buffer (e.g., containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, and 10% glycerol) to denature the proteins [14] [18].

- Second Dimension Run: Rinse the strip with deionized water and place it horizontally on top of a standard SDS-PAGE gel (e.g., 12% Laemmli gel). Seal the strip in place with 1% hot agarose solution. Perform the second dimension electrophoresis according to standard SDS-PAGE protocols [14].

The workflow for this powerful technique is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of these electrophoretic methods relies on a set of key reagents, each with a specific function.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Electrophoresis

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers a uniform negative charge, enabling separation by mass in SDS-PAGE [1] [19]. |

| Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 | Dye used in BN-PAGE to bind protein surfaces, imparting a negative charge for migration while maintaining native state [14] [8]. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) or 2-Mercaptoethanol | Reducing agents that break disulfide bonds within and between polypeptide chains, ensuring complete denaturation in SDS-PAGE [5]. |

| NuPAGE Precast Gels & Buffers | Pre-formulated, consistent gels and optimized buffers (e.g., MOPS SDS Running Buffer) for reproducible SDS-PAGE and related techniques [12]. |

| Molecular Weight Markers | A set of proteins of known molecular masses run alongside samples to calibrate and estimate the size of unknown proteins [1] [5]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to samples during extraction and solubilization to prevent protein degradation by endogenous proteases, preserving the sample's integrity [14]. |

| Dodecyl Maltoside | A mild, non-ionic detergent used to solubilize membrane protein complexes for BN-PAGE without disrupting protein-protein interactions [14] [18]. |

| Deoxynybomycin | Deoxynybomycin, CAS:27259-98-9, MF:C16H14N2O3, MW:282.29 g/mol |

| Deoxypheganomycin D | Deoxypheganomycin D, CAS:69280-94-0, MF:C30H47N9O11, MW:709.7 g/mol |

Method Selection and Concluding Workflow

The choice of separation method must be guided by the primary research question. The following decision pathway aids in selecting the most appropriate technique.

In conclusion, the landscape of protein separation offers a spectrum of techniques from fully denaturing to fully native. Traditional SDS-PAGE remains the cornerstone for analytical separation based on mass, while BN-PAGE and other native techniques are indispensable for functional interactome studies. The development of hybrid methods like NSDS-PAGE demonstrates the ongoing innovation in the field, providing researchers with powerful tools to balance high-resolution separation with the crucial preservation of biological function. The choice of method, therefore, is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with experimental objectives.

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D PAGE) is a powerful technique that provides a orthogonal view of the proteome by separating proteins based on two independent physical properties: isoelectric point (pI) and molecular weight. Unlike one-dimensional SDS-PAGE, which separates proteins primarily by mass, 2D PAGE resolves intact proteins with similar molecular weights but different pI values, and vice versa, enabling the detection of post-translational modifications (PTMs) and protein isoforms that are indistinguishable in single-dimension systems [20] [21]. This orthogonal separation principle is particularly valuable in clinical research settings for obtaining global disease information and monitoring disease progression through comprehensive protein expression profiling [21].

The fundamental advantage of 2D PAGE lies in its high resolution capacity to resolve complex protein mixtures. Where SDS-PAGE might display a single band, 2D PAGE can reveal multiple distinct protein spots, each representing a different isoform or PTM state [20]. This capability makes it an indispensable tool in proteomics research, especially for studying autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, where changes in acute-phase protein levels can be correlated with clinical improvement and conventional clinical chemistry measurements [21].

Comparative Data: 2D PAGE vs. SDS-PAGE

Table 1: Key characteristics and applications of 2D PAGE versus SDS-PAGE

| Parameter | 2D PAGE | SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| Separation Principles | First dimension: Isoelectric point (pI); Second dimension: Molecular weight | Single dimension: Molecular weight |

| Resolution Capacity | Can resolve thousands of proteins from complex mixtures [21] | Limited to tens to hundreds of protein bands |

| Detection of PTMs | Excellent for detecting charge-changing modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation) [20] | Limited capability; may show smearing or shifts in molecular weight |

| Sample Throughput | Lower throughput, more complex protocol [20] | Higher throughput, simpler protocol [22] |

| Required Sample Amount | 50 μg total protein or more for silver staining [21] | Can work with smaller amounts (e.g., 3-5 μg/μl) [22] |

| Detection Sensitivity | Approximately 0.2 ng per protein spot with silver staining [21] | High sensitivity with Western blotting (detection of specific proteins) [22] |

| Key Applications | Comprehensive proteomic profiling, PTM analysis, biomarker discovery [20] [21] | Protein size determination, abundance estimation, immunoblotting [22] |

Table 2: Quantitative protein detection limits of 2D PAGE with different staining methods

| Staining Method | Detection Limit | Linear Dynamic Range | Compatibility with Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver Staining | ~0.2 ng per protein spot [21] | Limited | Moderate (requires specific protocols for MS compatibility) [21] |

| Coomassie Blue | ~10-100 ng | Moderate | Excellent |

| Fluorescent Dyes | ~1-10 ng | Wide | Excellent |

| Sypro Ruby | ~1-10 ng | Wide | Excellent |

Experimental Protocol: Optimized 2D PAGE Methodology

Sample Preparation

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful 2D PAGE separation. For tissue samples such as mosquito or synovial fluid, homogenization or sonication is necessary to ensure complete cell lysis [22] [20]. Lysis should be performed on ice in the presence of protease inhibitors (e.g., 1-10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF) and phosphatase inhibitors (e.g., 1-2 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate) to prevent protein degradation and dephosphorylation [22].

Key considerations for sample preparation:

- Use chaotropic agents like 8M urea and 4% CHAPS for effective protein solubilization [21]

- Avoid heating samples containing urea to prevent protein carbamylation

- For difficult-to-solubilize proteins, use zwitterionic detergents like CHAPS [22]

- Remove insoluble debris by centrifugation at 10,000-15,000 × g for 15 minutes

- Determine protein concentration using compatible assays (BCA or Bradford) [22]

First Dimension: Isoelectric Focusing (IEF)

The isoelectric focusing dimension separates proteins according to their isoelectric points using immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips.

Protocol:

- Dilute protein samples (50 μg total protein) in 500 μl of IEF buffer containing 8M urea, 4% CHAPS, 40 mM Tris base, 65 mM DTT, and trace bromophenol blue [21]

- Load samples in sample cups at the cathodal end of 18-cm immobilized nonlinear pH 3-10 gradient strips

- Perform isoelectric focusing for a total of 99.9 kVh at 20°C [21]

- After focusing, equilibrate strips for 15 minutes at 37°C in equilibration buffer (0.375 M Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 6M urea, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol) containing 2% DTT, followed by 15 minutes in the same buffer with 2% iodoacetamide instead of DTT [21]

Second Dimension: SDS-PAGE

The second dimension separates proteins based on molecular weight under denaturing conditions.

Protocol:

- Cut approximately 2 cm from the cathodal end of the IPG strip and create a pointed tip at the anode end

- Transfer strips to the top of 18×16-cm, 1.5-mm thick 9-16% polyacrylamide gradient gels

- Secure strips with molten 0.5% agarose in cathode buffer containing trace bromophenol blue [21]

- Run gels at 10 mA/gel for the first hour followed by 40 mA/gel at constant 10°C until the bromophenol blue front reaches the bottom of the gel [21]

- Run samples in triplicate for statistical analysis

Protein Detection and Visualization

Silver Staining Protocol:

- Fix gels in 50% methanol, 5% acetic acid for at least 30 minutes

- Sensitize with 0.02% sodium thiosulfate for 2 minutes

- Wash with deionized water (3 × 5 minutes)

- Impregnate with 0.2% silver nitrate, 0.03% formaldehyde for 20 minutes

- Develop with 3% sodium carbonate, 0.05% formaldehyde

- Stop development with 5% acetic acid [21]

For mass spectrometry compatibility, use modified silver staining protocols that omit glutaraldehyde and use minimal formaldehyde [21].

Data Analysis and Protein Identification

Image Acquisition and Analysis

- Scan stained gels using a flatbed scanner at 200 dpi resolution or higher [21]

- Analyze spot patterns using specialized software (e.g., Phoretix, ImageMaster)

- Perform spot detection, background subtraction, and normalization

- Compare protein spot patterns across different experimental conditions

- Quantify changes in protein expression by densitometry of stained spots [21]

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

Protocol for in-gel tryptic digestion:

- Excise protein spots of interest from the gel

- Destain, reduce with DTT, and alkylate with iodoacetamide

- Digest in situ with trypsin overnight at 37°C [21]

- Extract peptides with 50% acetonitrile, 5% formic acid

- Analyze by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry or nanoelectrospray MS [21]

- Identify proteins by peptide mass fingerprinting using database search algorithms with mass accuracy of 0.1 Da [21]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for 2D PAGE experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| IPG Strips | First dimension separation by isoelectric point | 18-cm immobilized pH gradient strips, nonlinear pH 3-10 [21] |

| Urea | Chaotropic agent for protein denaturation and solubilization | 8M concentration in IEF buffer [21] |

| CHAPS | Zwitterionic detergent for protein solubilization | 4% concentration in IEF buffer [21] |

| DTT | Reducing agent for disulfide bond disruption | 65 mM in IEF buffer, 2% in equilibration buffer [21] |

| Iodoacetamide | Alkylating agent for cysteine modification | 2% in equilibration buffer [21] |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent protein degradation during sample preparation | 1-10 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM PMSF [22] |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | Prevent protein dephosphorylation | 1-2 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate [22] |

| Acrylamide/Bis-acrylamide | Matrix for second dimension SDS-PAGE | 9-16% gradient gels for optimal resolution [21] |

Workflow Visualization

2D PAGE Experimental Workflow

Orthogonal Data Integration

Orthogonal Separation Advantage

Applications in Biomedical Research

The orthogonal data provided by 2D PAGE has proven particularly valuable in clinical research settings. In rheumatoid arthritis studies, synovial fluid proteins from microliter volumes could be resolved into several hundred distinct spots, enabling quantification of acute-phase protein changes in response to anti-CD4 antibody treatment [21]. The sensitivity of this method (approximately 0.2 ng from a total of 50 μg of protein loaded) allows monitoring of protein expression changes that correlate with clinical improvement and conventional clinical chemistry measurements [21].

In mosquito proteomic profiling, optimized 2D PAGE protocols have improved protein solubility, resolution, and visualization, enabling the resolution of complex proteomic data that is difficult to analyze through shotgun proteomic approaches alone [20]. This is particularly important for identifying immunogenic proteins to combat vector-borne diseases, as 2D PAGE can separate post-translationally modified proteins that are not distinguished through standard proteomic analysis [20].

The orthogonal advantage of 2D PAGE thus provides complementary data that enhances our understanding of proteome complexity, enabling researchers to detect protein modifications, quantify expression changes, and discover biomarkers that would remain hidden with single-dimension separation techniques.

Two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) that combines native and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) separation is a powerful analytical technique for studying protein complexes under non-denaturing conditions. Unlike conventional 2D electrophoresis that uses isoelectric focusing in the first dimension, this method utilizes blue native (BN)-PAGE to separate intact protein complexes based on their size and shape, followed by SDS-PAGE to denature and separate the individual subunits by molecular weight [14]. This approach preserves protein-protein interactions that are crucial for understanding biological systems, making it invaluable for both basic research and drug development pipelines.

The fundamental principle of this technique lies in its ability to resolve protein mixtures in their native state during the first dimension separation. The Coomassie Blue G-250 dye used in BN-PAGE binds to protein surfaces, conferring a negative charge that facilitates migration toward the anode while maintaining complex integrity [8]. Subsequent second-dimension separation under denaturing conditions dissociates these complexes into their constituent polypeptides, creating a 2D map where protein interactions can be visualized and analyzed.

Theoretical Foundation and Methodological Principles

Fundamental Separation Mechanisms

The resolving power of 2D native/SDS-PAGE stems from its exploitation of different protein properties in each dimension:

First Dimension (BN-PAGE): Separation occurs based on the size and native charge of protein complexes. The Coomassie dye provides the necessary negative charge for electrophoretic mobility while maintaining physiological interactions [14] [8]. The migration distance is inversely proportional to the logarithm of the complex mass, allowing for size estimation.

Second Dimension (SDS-PAGE): Separation is based strictly on molecular weight under denaturing conditions. SDS binds to polypeptides at a constant ratio, masking native charge and creating uniform charge density [22]. This dissociates complexes into subunits while providing molecular weight information.

This orthogonal separation strategy enables researchers to distinguish between stable protein complexes and transient interactions, information that is lost in fully denaturing electrophoretic techniques.

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional 2D-PAGE

When compared to the standard IEF/SDS-PAGE system, the native/SDS approach offers several distinct advantages for studying protein interactions:

Table: Comparison of 2D Electrophoresis Techniques

| Parameter | IEF/SDS-PAGE | Native/SDS-PAGE |

|---|---|---|

| First Dimension Basis | Isoelectric point | Native size and shape |

| Protein Complex Preservation | No | Yes |

| Throughput | Lower | Higher |

| Cost | Higher (specialized strips, reagents) | Lower |

| Compatibility with Activity Assays | Limited | Excellent |

| Resolution of Hydrophobic Proteins | Challenging | Enhanced |

The native/SDS-PAGE system serves as a "useful complement to the standard 2D gel electrophoresis system for analyzing complicated protein mixture, especially for the study of protein interactions" [13]. Its ability to maintain biological activity post-separation enables direct functional analyses that are not possible with denaturing techniques.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for 2D BN/SDS-PAGE

Sample Preparation

- Cell Lysis: Suspend 10ⷠcells in 500 μL of BN lysis buffer (25 mM BisTris-HCl, 20% glycerol, pH 7.0) supplemented with 2% dodecyl maltoside and protease inhibitor mixture [14].

- Extraction: Incubate on ice for 40 minutes, then centrifuge at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 30 minutes.

- Protein Quantification: Determine protein concentration using compatible assays (e.g., RC DC assay). Adjust concentration to >0.5 μg/μL [22].

First Dimension (BN-PAGE)

- Gel Preparation: Prepare a 5-13.5% gradient separating gel with a 4% stacking gel [14].

- Sample Loading: Mix 80 μg protein with BN sample buffer (1× BisTris-ACA, 30% glycerol, 5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250).

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Run at 4°C overnight using cathode buffer (50 mM Tricine, 15 mM BisTris, 0.01% Coomassie Blue) and anode buffer (50 mM BisTris-HCl, pH 7.0).

Second Dimension (SDS-PAGE)

- Gel Excison: Excise differentiated protein complex bands from BN-PAGE.

- Equilibration: Equilibrate gel strips for 30 minutes in 1× SDS loading buffer at room temperature [14].

- Second Dimension Run: Place strips on 12% Laemmli SDS gel, seal with 1% hot agarose, and run according to standard protocols.

Activity Staining and Western Blotting

To leverage the functional preservation offered by this technique:

- Zymography: After electrophoresis, incubate gels in appropriate buffers to detect enzymatic activities (e.g., proteolytic, esterase) without fixation [8].

- Western Blotting: Transfer proteins to membranes for immunodetection using specific antibodies [23].

- Supershift Assays: Pre-incubate samples with antibodies before BN-PAGE to verify protein identities through mobility shifts [14].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for two-dimensional native/SDS-PAGE analysis

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Reagents for 2D Native/SDS-PAGE

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Detergents | Dodecyl maltoside, Triton X-100, CHAPS | Solubilize membrane proteins while preserving native interactions [14] [22] |

| Protease Inhibitors | PMSF (1 mM), Aprotinin (2 μg/mL), Leupeptin (1-10 μg/mL) | Prevent protein degradation during extraction [22] |

| Phosphatase Inhibitors | β-glycerophosphate (1-2 mM), Sodium orthovanadate (1 mM) | Preserve phosphorylation states [22] |

| Electrophoresis Buffers | BisTris-ACA, Tricine, Coomassie Blue G-250 | Maintain native conditions while providing charge for migration [14] |

| Specialized Lysis Buffers | NP-40 buffer, RIPA buffer, Tris-HCl | Extract proteins from specific subcellular compartments [22] |

Applications in Basic Research

Elucidating Host-Virus Protein Interactions

The 2D BN/SDS-PAGE technique has proven invaluable for studying viral infection mechanisms. In hepatitis B virus (HBV) research, comparative analysis of HepG2 and HepG2.2.15 cells revealed unique protein complexes in HBV-expressing cells [14]. Mass spectrometry identification showed that nearly 20% of these proteins were heat shock proteins (HSP60, HSP70, HSP90), which were found to physically interact specifically in HBV-infected cells.

Functional validation through RNA interference demonstrated that downregulation of HSP70 or HSP90 significantly inhibited HBV viral production without affecting cellular proliferation or apoptosis [14]. This application highlights how the technique can identify critical host factors required for viral replication, revealing potential therapeutic targets.

Analysis of Snake Venom Proteomics

In toxinology research, 2D BN/SDS-PAGE has been applied to characterize protein complexes in Brazilian Bothrops snake venoms [8]. This approach revealed that snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs) and serine proteinases (SVSPs) maintain enzymatic activity after electrophoresis, enabling functional characterization alongside compositional analysis.

The technique successfully identified C-type lectin-like proteins (CTLPs) through Western blotting and demonstrated the presence of native protein complexes that may enhance venom toxicity [8]. This application showcases the method's utility in analyzing complex biological mixtures with direct implications for antivenom development.

Applications in Drug Development

Target Identification and Validation

The 2D native/SDS-PAGE approach facilitates drug target discovery by:

- Identifying multiprotein complexes that serve as functional units in disease pathways [14]

- Revealing disease-specific protein interactions not present in normal cells

- Validating target engagement through supershift assays with therapeutic antibodies [14]

In the HBV study, the technique confirmed that HSP90 inhibition with 17-AAG significantly reduced viral secretion, validating this chaperone machinery as a therapeutic target for HBV-associated diseases [14].

Mechanism of Action Studies

For drug development, understanding how therapeutic agents affect protein complexes is crucial:

- Compound Screening: Assess how small molecules disrupt or stabilize specific protein interactions

- Biomarker Identification: Discover complex formation or dissociation events that correlate with treatment response

- Off-Target Effects: Identify unintended interactions with non-target protein complexes

Figure 2: Drug development pipeline leveraging 2D native/SDS-PAGE findings

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Quantitative Analysis of Protein Complexes

Effective interpretation of 2D native/SDS-PAGE data requires careful analysis:

- Spot Pattern Recognition: Identify vertical alignments indicating proteins originating from the same native complex

- Molecular Weight Determination: Compare subunit masses from SDS-PAGE with complex sizes from BN-PAGE to determine stoichiometry

- Comparative Analysis: Use software tools (e.g., PD Quest Advanced 2-D Analysis) to detect differences between experimental conditions [23]

Troubleshooting Common Technical Challenges

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for 2D Native/SDS-PAGE

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Streaking in Second Dimension | Protein diffusion during native PAGE [13] | Optimize incubation time in SDS buffer; use sharper gel excision |

| Poor Complex Resolution | Inappropriate detergent concentration | Titrate detergent concentration; switch detergent type based on protein characteristics [22] |

| Loss of Enzyme Activity | Over-denaturation during transfer | Shorten equilibration time; avoid reducing agents in first dimension [8] |

| Low Protein Yield | Insufficient solubilization | Optimize lysis buffer composition; include chaotropic agents for difficult proteins [22] |

Two-dimensional native/SDS-PAGE represents a powerful methodology that bridges basic biological discovery and therapeutic development. Its unique capacity to preserve protein interactions while providing high-resolution separation makes it indispensable for studying complex biological systems. As demonstrated in both virology and toxinology research, this technique can reveal critical protein complexes that serve as functional units in disease processes, thereby identifying new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Future developments will likely enhance the technique's throughput and sensitivity through integration with advanced mass spectrometry methods and label-free quantification approaches. The continued application of 2D native/SDS-PAGE in drug discovery pipelines promises to accelerate the identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets, particularly for diseases involving multiprotein complexes that have historically been challenging to target with conventional approaches.

Implementing 2D Native-SDS PAGE: Step-by-Step Protocols and Research Applications

Sample Preparation Strategies for Preserving Native Complexes and Ensuring Complete Denaturation

Within structural biology and proteomics, the integrity of a protein sample—whether meticulously preserved in its native state or completely denatured—is a foundational determinant for the success of subsequent analytical techniques. This application note details standardized protocols for preparing protein samples for two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) utilizing native PAGE in the first dimension and SDS-PAGE in the second. The objective is to provide researchers with clear methodologies to either maintain native protein complexes for interaction studies or achieve complete denaturation for mass-based separation, thereby supporting a wide range of research from basic protein characterization to drug development.

Core Principles: Native vs. Denaturing Conditions

The choice between native and denaturing conditions dictates the type of information obtained from an experiment. Table 1 summarizes the key differences in the resulting protein properties and the primary analytical separation mechanisms under these two fundamental conditions.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Native vs. Denaturing Sample Preparation

| Parameter | Native Conditions | Denaturing Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure | Folded, tertiary/quaternary structure preserved [24] | Unfolded, primary structure only [1] |

| Non-covalent Interactions | Preserved (protein-protein, ligand-binding) [13] [24] | Disrupted [25] |

| Typical Buffer | Near-neutral pH, non-denaturing salts (e.g., Ammonium Acetate) [25] [26] | Organic solvents, acidic pH, SDS [25] [1] |

| Charge in ESI-MS | Lower, narrower distribution [25] | Higher, wider distribution [25] |

| Primary Separation Mechanism | Mass/charge ratio and shape [1] | Molecular mass [1] |

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting the appropriate sample preparation strategy based on research objectives.

Protocol 1: Preserving Native Complexes for Analysis

Background and Applications

Preserving native complexes allows for the analysis of proteins in their functional, folded states, maintaining their quaternary structure and non-covalent interactions with binding partners. This is essential for techniques like native-PAGE, which separates proteins based on their mass-to-charge ratio and shape [1], and native mass spectrometry (native MS), which directly characterizes intact protein complexes [25] [24]. A key application is a native/SDS 2D-PAGE system, where the first dimension (native PAGE) preserves protein interactions, and the second dimension (SDS-PAGE) denatures and separates the constituent polypeptides, allowing the identification of interacting proteins through mobility shifts on the 2D map [13].

Detailed Methodology: Buffer Exchange for Native MS

The following protocol for buffer exchange into volatile ammonium acetate is critical for successful native MS analysis and can also be utilized for other native analyses [26].

Materials:

- Micro Bio-Spin 6 chromatography columns (Bio-Rad, cat. no. 732-6221) or similar centrifugal concentrators.

- Ammonium acetate solution (50-200 mM, pH ~7).

- Clean 2 mL Eppendorf tubes.

- Microcentrifuge.

Procedure:

- Resuspend Gel: Invert the Bio-Spin column sharply several times to resuspend the settled gel and remove any bubbles.

- Remove Packing Buffer: Snap off the tip and place the column in a provided 2 mL waste tube. Remove the cap and allow the excess packing buffer to drain by gravity to the top of the gel bed. Discard the drained buffer.

- Initial Centrifugation: Place the column back into the waste tube and centrifuge for 2 minutes at 1,000 × g in a swinging-bucket centrifuge. Discard the flow-through.

- Equilibrate Column: Apply 500 µL of ammonium acetate buffer to the column. Centrifuge for 1 minute at 1,000 × g. Discard the flow-through. Repeat this equilibration step 3-5 times. On the final wash, using 450 µL of buffer can help avoid excessive sample dilution.

- Apply Sample: Place the column in a clean 2.0 mL Eppendorf tube. Carefully apply your protein sample (25–80 µL) directly to the center of the gel bed.

- Elute Sample: Centrifuge the column for 4 minutes at 1,000 × g. The purified protein, now in ammonium acetate buffer, will be collected in the bottom of the Eppendorf tube and is ready for immediate analysis.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Speed and Cold: For proteins prone of dissociation, keep the procedure cool and work swiftly.

- Sample Concentration: The initial protein concentration should be higher than the final desired concentration (typically 1-25 µM for native MS [26]) to account for dilution during the buffer exchange.

- Glycerol and Salts: Avoid glycerol in protein stocks, as it causes peak broadening in MS [26]. Ensure salt concentrations are at or below the molar concentration of the protein.

Protocol 2: Ensuring Complete Denaturation for Analysis

Background and Applications

Complete denaturation is required for techniques that rely on separating proteins by their molecular weight alone, such as SDS-PAGE [1], or for accessing the full sequence in bottom-up proteomics. Denaturation unfolds the protein, disrupts non-covalent interactions, and, with reducing agents, cleaves disulfide bonds. A recent advancement, denaturing Mass Photometry (dMP), offers a rapid and sensitive alternative to SDS-PAGE for optimizing cross-linking reactions, providing accurate mass identification and quantification of denatured species from 30 kDa to 5 MDa [27].

Detailed Methodology: Denaturation for Mass Photometry

This robust 2-step protocol ensures >95% irreversible denaturation within 5 minutes [27].

Materials:

- Denaturant Stock: 6 M Guanidine Hydrochloride (GdnHCl) or 5.4 M Urea.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS).

- Mass Photometer and calibrated sample slides.

Procedure:

- Denaturation Reaction: Incubate the protein sample with an equal volume of 6 M GdnHCl (or 5.4 M Urea) at room temperature for 5 minutes. This achieves a final denaturant concentration of 3 M GdnHCl or 2.7 M Urea in the reaction.

- Dilution for Measurement: Dilute the denatured sample approximately 10-fold in PBS to lower the denaturant concentration below 0.8 M, which is compatible with stable Mass Photometry droplet formation. For example, add 2 µL of the denaturation reaction to 18 µL of PBS.

- Immediate Measurement: Load 10-20 µL of the diluted sample onto a Mass Photometry slide and acquire data immediately. The entire process from start to data acquisition can be completed in under 10 minutes.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Denaturant Choice: GdnHCl is a stronger denaturant than Urea, but Urea achieved >95% denaturation for all tested complexes (ADH, GLDH, 20S proteasome) in just 5 minutes [27].

- Irreversibility: This protocol produces irreversibly denatured proteins, ideal for snapshot analysis.

- Throughput: This dMP protocol is significantly faster than SDS-PAGE, requires 20-100 times less material, and provides single-molecule sensitivity and direct quantification [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful sample preparation relies on the appropriate selection of reagents. Table 2 lists key solutions and their specific functions in either native or denaturing protocols.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Native and Denaturing Protein Preparation

| Reagent Solution | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Acetate (50-200 mM, pH ~7) | Volatile buffer for native MS and native-PAGE; preserves non-covalent interactions [25] [26]. | Maintains proteins in a folded state; compatible with ESI-MS [26]. |

| n-Dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (β-DM) & Digitonin | Non-ionic detergents for solubilizing membrane protein complexes in native state for BN-PAGE [28]. | A 1% (w/V) mixture of each provides gentle solubilization while preserving mega-complexes [28]. |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Ionic detergent for denaturing PAGE; binds proteins and confers uniform negative charge [1]. | Unfolds proteins; separation is primarily by molecular mass [1]. |

| Guanidine Hydrochloride (GdnHCl) | Strong chaotropic denaturant for complete protein unfolding [27]. | More effective than Urea for rapid denaturation; use at 3-6 M concentration [27]. |

| Urea | Chaotropic denaturant; disrupts hydrogen bonding to unfold proteins [27]. | Effective at 2.7-5.4 M; achieved >95% denaturation in 5 min in dMP protocol [27]. |

| Micro Bio-Spin 6 Columns | Size-exclusion chromatography columns for rapid buffer exchange (≤30 min) [26]. | MW exclusion limit 6 kDa; ideal for removing non-volatile salts and small molecules [26]. |

| Deoxyshikonin | Deoxyshikonin, CAS:43043-74-9, MF:C16H16O4, MW:272.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Desvenlafaxine hydrochloride | Desvenlafaxine hydrochloride, CAS:300827-87-6, MF:C16H26ClNO2, MW:299.83 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Outcomes

The choice of sample preparation directly impacts the quantitative and qualitative results of an analysis. Table 3 compares key performance metrics for native and denaturing conditions as revealed by mass spectrometry and mass photometry.