Advanced Strategies for High Molecular Weight Protein Resolution: From Western Blotting to Structural Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to overcome the significant challenges associated with analyzing high molecular weight (HMW) proteins.

Advanced Strategies for High Molecular Weight Protein Resolution: From Western Blotting to Structural Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to overcome the significant challenges associated with analyzing high molecular weight (HMW) proteins. Covering foundational principles, optimized methodologies for separation and transfer, targeted troubleshooting, and advanced validation techniques, we synthesize current best practices from gel-based analysis to cutting-edge structural biology. The protocols and insights detailed here are essential for reliable detection and characterization of large proteins and complexes, which are critical targets in signaling pathway analysis, structural biology, and therapeutic development.

Understanding the Unique Challenges of High Molecular Weight Proteins

Why HMW Proteins Behave Differently in Separation Systems

In the pursuit of improving the resolution of high molecular weight (HMW) proteins, researchers face distinct biochemical and physical challenges. Proteins with a molecular mass typically greater than 100 kDa are fundamental to processes like cytoskeleton formation, defense and immunity, transcription, and translation [1]. However, their large size and complex domain structures cause them to behave differently during standard separation protocols compared to their lower molecular weight counterparts. Their long polypeptide chains are more susceptible to proteolytic degradation during purification and they have a greater tendency to form aggregates, particularly under denaturing conditions [1]. Understanding these inherent characteristics is the first step in troubleshooting common experimental issues and developing robust methods for their analysis, which is critical for advancing research and drug development focused on these biologically significant targets.

FAQs: Fundamental Principles of HMW Protein Behavior

1. Why do HMW proteins often appear as smears or fail to transfer properly in western blotting? HMW proteins migrate with more difficulty through the dense matrix of polyacrylamide gels and can become trapped, leading to poor resolution and inefficient transfer to membranes. Their large size results in slower migration during electrophoresis and blotting. Furthermore, they are more prone to aggregation during sample preparation, which can create heterogeneous populations of protein that manifest as smears instead of sharp bands [2] [1].

2. What makes HMW proteins more difficult to purify? The primary challenges are aggregation and proteolysis. Their long polypeptide chains present more targets for endogenous proteases during purification. Additionally, hydrophobic regions on these large proteins can interact, causing them to aggregate in solution, which leads to loss of protein and clogged chromatography columns [1]. Special care must be taken to avoid high local protein concentrations during steps like buffer exchange to prevent this undesirable phase separation [3].

3. Why is standard 2D-gel electrophoresis particularly unsuitable for HMW proteins? Conventional 2D-gel methods with polyacrylamide gels for the first dimension (isoelectric focusing) struggle with proteins larger than 200 kDa. These large proteins enter the gel matrix inefficiently and may not migrate effectively, leading to their loss. A modified technique using agarose gels for the first dimension (agarose 2-DE) has been shown to significantly improve the separation of HMM proteins ranging from 150 kDa up to 500 kDa [1].

4. How does protein "supersaturation" or "marginal stability" affect HMW proteins? A large fraction of cellular proteins, including many HMW proteins, are "marginally stable," meaning they are on the verge of misfolding or aggregation. This is often a trade-off between structural flexibility for function and maximum stability. Even mild physiological fluctuations or stress conditions can trigger these metastable proteins to unfold, expose hydrophobic surfaces, and undergo phase separation or aggregation [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Transfer of HMW Proteins in Western Blotting

A common issue is the incomplete transfer of proteins >150 kDa from the gel to the membrane, resulting in weak or absent signal.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient Transfer Time | Increase transfer time. For rapid dry transfer systems, increase from a standard 7 minutes to 8-10 minutes [2]. |

| Inappropriate Gel Matrix | Switch to a gel with a more open pore structure. Tris-acetate gels (e.g., 3-8%) are superior to Bis-Tris or Tris-glycine gels for HMW proteins [2]. |

| Inefficient Elution from Gel | Add SDS (0.01-0.02%) to the transfer buffer to help elute large proteins from the gel matrix [5]. |

| Protein Aggregation | Pre-equilibrate the gel in transfer buffer containing 0.02-0.04% SDS for 10 minutes before assembling the transfer sandwich [5]. |

| Methanol Concentration | Optimize methanol in transfer buffer (typically 10-20%). Methanol helps bind protein to membrane but can shrink the gel pores, hindering HMW protein elution [5]. |

Problem 2: Low Yield and Aggregation During Protein Purification

HMW proteins are often lost during purification due to aggregation, adherence to surfaces, or proteolysis.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| High Local Protein Concentration | Avoid high local concentrations in centrifugal filter devices by using short spin times and frequent mixing of the solution [3]. |

| Non-optimal Buffer Conditions | Systematically modify buffer conditions. Temperature is a strong parameter; for some proteins, purification at room temperature instead of 4°C prevents phase separation [3]. |

| Proteolytic Degradation | Include a cocktail of protease inhibitors in all lysis and purification buffers [1]. |

| Protein Phase Separation | If the solution becomes turbid, adjust interaction parameters like ionic strength, pH, or temperature to dissolve the condensed liquid droplets [3]. |

Problem 3: Broad or Tailing Peaks in Affinity Chromatography

Broad peaks or the target protein eluting over a wide volume can indicate non-specific binding or suboptimal elution conditions.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Weak or Slow Elution | Try different elution conditions. For competitive elution, increase the concentration of the competing ligand in the elution buffer [6]. |

| Slow Binding Kinetics | Allow more time for binding by stopping the column flow for a few minutes after sample application or applying the sample in multiple aliquots with flow pauses in between [6]. |

| Non-specific Binding | Optimize the composition of the binding and wash buffers (e.g., adjust salt concentration, add mild detergents) to reduce non-specific interactions without disrupting the specific affinity binding [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Purification of a Phase-Separating HMW Protein (e.g., LAF-1)

This protocol outlines strategies to prevent phase separation and aggregation during purification [3].

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Lysis Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton-X, plus fresh lysozyme, protease inhibitors, and β-mercaptoethanol.

- Nickel Wash Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, plus β-mercaptoethanol.

- Nickel Elution Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, plus β-mercaptoethanol.

- Heparin Binding Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 50 mM NaCl, 1% glycerol, plus DTT.

- Heparin Elution Buffer: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 M NaCl, 1% glycerol, plus DTT.

Detailed Workflow:

- Cell Growth and Induction: Induce protein expression in E. coli at a relatively low OD600 (~0.4) to minimize protein loss to the insoluble fraction. Grow cultures overnight at 18°C after induction.

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend cell pellet in chilled lysis buffer. Incubate on ice for 30-60 minutes. Sonicate on ice and centrifuge at 20,000 × g for 30 minutes to obtain cleared lysate.

- Batch Purification with Nickel Resin: Perform a "batch" purification by incubating the cleared lysate with pre-washed nickel resin for 30 minutes at 4°C with gentle rocking. This avoids creating high local concentrations on a packed column.

- Wash and Elution: Distribute the lysate-bead mixture into tubes, centrifuge to collect beads, and pour off the flow-through. Wash the beads with nickel wash buffer. Elute the protein using nickel elution buffer. Perform these steps at room temperature if the protein is prone to phase separation at colder temperatures.

- Further Purification (Heparin Column): Dialyze the eluted protein into heparin binding buffer. Purify further using a heparin column with a salt gradient elution (heparin elution buffer).

Protocol 2: Optimized Western Blot Transfer for HMW Proteins (>150 kDa)

This protocol ensures efficient transfer and detection of HMW proteins [2].

Key Reagents and Solutions:

- Tris-Acetate Gels (3-8%)

- Transfer Buffer (with or without 0.01% SDS)

- 20% Ethanol in deionized water

- Nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane (0.2 µm pore size for proteins <10 kDa, 0.45 µm for larger proteins)

Detailed Workflow:

- Gel Electrophoresis: Separate proteins using a 3-8% Tris-acetate gel. This gel type provides an open matrix that allows HMW proteins to migrate effectively, enabling better transfer later.

- Gel Equilibration (Optional but Recommended): If using a Bis-Tris or Tris-glycine gel, submerge the gel in 20% ethanol for 5-10 minutes at room temperature with shaking. This step removes salts and can help shrink the gel to its final size, improving transfer efficiency. This step may not be necessary for Tris-acetate gels.

- Membrane Preparation: Pre-wet the nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane in methanol (for PVDF) then transfer buffer.

- Assemble Transfer Sandwich: Assemble the transfer stack correctly to ensure good contact between the gel and membrane. Remove all air bubbles by rolling a glass pipette over the surface.

- Transfer: Transfer using an appropriate system. For rapid dry transfer systems, use a program of 20-25 V for 8-10 minutes instead of the standard 7 minutes to allow slower-moving HMW proteins to exit the gel completely [2].

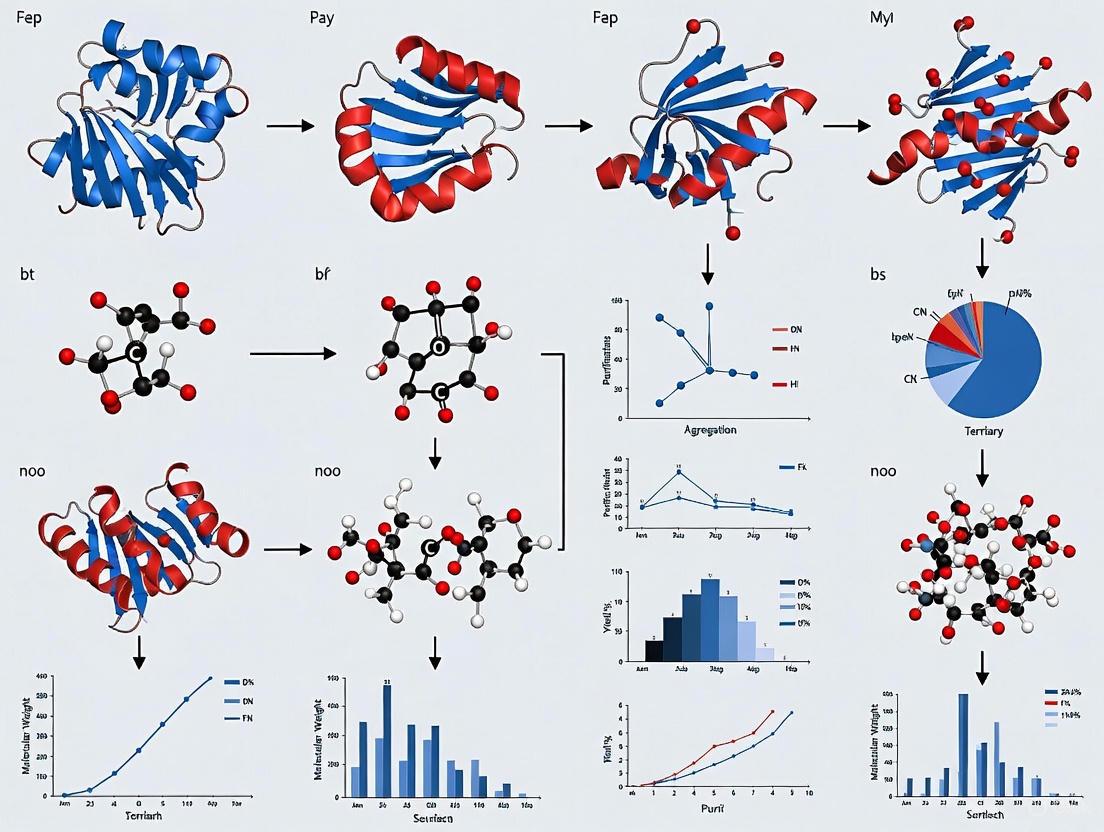

Diagram 1: The Cascade of Challenges in HMW Protein Separation. This flowchart outlines how the intrinsic properties of HMW proteins lead to common experimental problems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials crucial for successfully working with HMW proteins.

| Research Reagent | Function in HMW Protein Work |

|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate Gels (3-8%) | Polyacrylamide gels with a larger pore size that allow for better separation and migration of HMW proteins during electrophoresis [2]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Essential additives to lysis and purification buffers that prevent proteolytic degradation of the long, susceptible polypeptide chains of HMW proteins [1]. |

| Chaotropic Agents (Urea, Thiourea) | Used in extraction buffers to disrupt hydrogen bonding and help solubilize HMW proteins that tend to aggregate, though they may require subsequent refolding steps [1]. |

| Detergents (e.g., CHAPS, Triton X-100) | Crucial for solubilizing membrane-associated HMW proteins and preventing non-specific aggregation during purification [1]. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins | Resins with immobilized ligands (e.g., antibodies, DNA, metal ions) allow for highly specific, preparative isolation of target HMW proteins from complex mixtures [1]. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | A gentle technique used as a final polishing step to separate monomers of the target HMW protein from unwanted aggregates or degraded fragments [7]. |

| Reducing Agents (DTT, β-mercaptoethanol) | Added to buffers to break disulfide bonds that can form within or between large polypeptide chains, preventing improper folding and aggregation [3]. |

| Thiabendazole-13C6 | Thiabendazole-13C6, CAS:2140327-29-1, MF:C10H7N3S, MW:207.21 g/mol |

| HEPES-d18 | HEPES-d18, MF:C8H18N2O4S, MW:256.42 g/mol |

Diagram 2: A Multi-Step Purification Workflow for HMW Proteins. This diagram illustrates a sequential purification strategy, highlighting key chromatography techniques used to isolate and purify HMW proteins while minimizing aggregation and loss.

Key Bottlenecks in Gel Electrophoresis and Membrane Transfer

Troubleshooting Guides

Gel Electrophoresis Troubleshooting

Problem 1: Distorted or "Smiling" Bands Bands curve upwards at the edges, resembling a smile.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Uneven heat distribution across the gel (Joule heating) [8]. | Run the gel at a lower voltage; use a power supply with constant current mode [8]. |

| High salt concentration in samples, creating local heating [8]. | Desalt samples or dilute them to reduce salt concentration [8]. |

| Overloading wells with too much sample [8]. | Load a smaller volume or concentration of sample [8] [9]. |

| Incorrect buffer concentration or depleted buffer [8]. | Use fresh, correctly prepared running buffer [8]. |

Problem 2: Band Smearing and Poor Resolution Bands appear as diffuse, fuzzy smears instead of sharp, distinct lines.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Sample degradation by nucleases or proteases [8]. | Handle samples gently; keep on ice; use sterile, nuclease-free reagents and tubes [8] [9]. |

| Running voltage too high, causing overheating and denaturation [8] [10]. | Reduce voltage and extend run time [8] [10]. |

| Incorrect gel concentration (pore size) [8]. | Use a lower % agarose (for DNA) or acrylamide (for protein) for larger molecules; higher % for smaller molecules [8]. |

| Incomplete denaturation of protein samples [8]. | Ensure protein samples are properly denatured with SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or BME) and boiled [8] [11]. |

Problem 3: Faint or Absent Bands No bands are visible after staining, or bands are very weak.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient sample concentration loaded onto the gel [8] [9]. | Increase the amount of starting material; confirm sample concentration before loading [8]. |

| Sample degradation during preparation or storage [8]. | Re-check sample preparation protocols; use fresh protease inhibitors [8] [11]. |

| Errors in electrophoresis setup (e.g., power supply not connected correctly) [8]. | Verify all power supply connections and settings; ensure current is flowing [8]. |

| Incorrect staining protocol [8]. | Prepare fresh staining solutions; ensure staining duration is adequate [8] [9]. |

Membrane Transfer Troubleshooting (Western Blotting)

Problem 1: Inefficient Transfer of High Molecular Weight (HMW) Proteins HMW proteins fail to transfer out of the gel or do so poorly.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Proteins are too large to elute efficiently from the gel [5] [11]. | Add 0.01-0.04% SDS to the transfer buffer to help elute proteins [5] [11]. |

| Methanol concentration is too high, causing gel shrinkage and trapping HMW proteins [5] [11]. | Reduce methanol in transfer buffer to 5-10% [5] [11]. |

| Transfer time is too short for large proteins to migrate [5] [11]. | Increase transfer time (e.g., 3-4 hours for wet transfer) [11]. |

| Incomplete reduction of disulfide bonds, leaving proteins tightly folded [12]. | Use fresh reducing agent (DTT or BME) in loading buffer and boil samples thoroughly [12]. |

Problem 2: High Background or Non-Specific Signal The entire membrane is stained, obscuring specific bands.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Ineffective blocking of the membrane [12] [11]. | Optimize blocking conditions; use 5% non-fat dry milk or 3% BSA; avoid milk with anti-goat/sheep antibodies [12]. |

| Antibody concentration is too high [12]. | Titrate primary and/or secondary antibody to find optimal dilution [12]. |

| Insufficient washing after antibody incubations [12]. | Increase wash volume, time, and number of changes; ensure wash buffer contains 0.05-0.1% Tween-20 [12] [11]. |

| Gel overloaded with too much total protein [12]. | Load ≤10 μg of total protein per lane; use immunoprecipitation to enrich for your target [12]. |

Problem 3: Loss of Low Molecular Weight (LMW) Proteins ("Blow-Through") Small proteins pass through the membrane and are lost.

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Pore size of the membrane is too large [5]. | Use a membrane with a 0.2 μm pore size instead of 0.45 μm to better retain LMW proteins [5] [11]. |

| Transfer time is too long, allowing small proteins to pass through [11]. | Reduce the transfer time [11]. |

| Methanol concentration is too low, reducing protein binding to the membrane [5]. | Ensure methanol concentration is 10-20% to promote protein binding [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why are my protein bands "smiling," and how can I fix it? "Smiling" bands are typically caused by uneven heating across the gel, where the center becomes hotter than the edges. To resolve this, run your gel at a lower voltage, use a constant current power supply if available, and consider running the gel in a cold room or with a cooling apparatus to dissipate heat evenly [8] [10].

My Western blot has no signal for my high molecular weight protein, but the ladder transferred fine. What should I check? This indicates a transfer problem specific to large proteins. First, ensure your transfer buffer contains a low concentration of SDS (0.01-0.04%) to help elute the large proteins from the gel. Second, reduce the methanol concentration in the transfer buffer to 5-10% to prevent gel shrinkage that traps HMW proteins. Finally, extend the transfer time to several hours [5] [11].

How can I prevent my low molecular weight protein from being lost during transfer? To prevent "blow-through," use a membrane with a smaller pore size (0.2 μm) to physically trap smaller proteins. Additionally, avoid over-transferring by optimizing and potentially shortening the transfer time. You can also try adding a second membrane behind the first to capture any proteins that pass through [12] [5].

What is the single most important factor for improving band resolution in a gel? The gel concentration is the most critical factor. Selecting a gel matrix with a pore size optimized for the specific size range of your target molecules is essential for achieving sharp, well-resolved bands. Using a gel with pores that are too large will not separate small molecules effectively, while pores that are too small will impede the migration of large molecules [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Sieving Agarose | Ideal for separating small DNA fragments (20-800 bp), providing resolution comparable to polyacrylamide gels [9]. |

| Protease/Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails | Added to lysis buffers to prevent protein degradation and maintain post-translational modifications during sample preparation [11]. |

| Prestained Protein Marker | Allows visual tracking of electrophoresis and transfer efficiency; molecular weight standards are visible on the membrane [12]. |

| PVDF Membrane (0.2 μm) | Offers higher protein binding capacity than nitrocellulose, especially for low molecular weight proteins. Essential for capturing small proteins [5] [11]. |

| Anti-Light Chain Specific Secondary Antibody | Critical for Western blotting after immunoprecipitation; prevents detection of the IP antibody heavy chain (50 kDa), avoiding obscuration of target proteins [12]. |

| Glycosidase (e.g., PNGase F) | Enzyme used to cleive N-glycans from glycoproteins; confirms if smearing is due to heterogeneous glycosylation [11]. |

Experimental Workflow for High-Resolution Protein Analysis

The following diagram outlines a detailed protocol for optimizing the separation and transfer of high molecular weight proteins, incorporating solutions to key bottlenecks.

The Critical Role of Gel Matrix Pore Size and Chemistry

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my high molecular weight protein not separating properly and appearing smeared? Improper separation of high molecular weight (HMW) proteins, often seen as smearing, is frequently caused by using a gel matrix with pores that are too small. HMW proteins (>150 kDa) require gels with a more open structure to migrate effectively [13] [14]. Other common causes include incomplete protein denaturation, overloading the gel with too much protein, or running the gel at an excessively high voltage, which generates heat and can cause band distortion [15] [14]. Ensure your sample is properly denatured by boiling with SDS and DTT, use a low-percentage polyacrylamide or Tris-acetate gel, and run the gel at a lower voltage for a longer time [13] [14].

2. What is the best type of gel for resolving proteins over 150 kDa? For optimal resolution of HMW proteins, low-percentage polyacrylamide gels or specialized Tris-acetate gels are recommended [13]. Standard Tris-glycine gels, especially 4-20% gradients, compact HMW proteins at the top, leading to poor resolution and transfer [13]. A 3-8% Tris-acetate gel provides an open matrix structure that allows HMW proteins to migrate farther, resulting in significantly better separation and transfer efficiency [13].

3. How can I improve the transfer efficiency of my high molecular weight protein for western blotting? Successful transfer of HMW proteins requires optimizing both the gel and transfer conditions [13].

- Gel Choice: Start with a gel that offers good HMW separation, like a 3-8% Tris-acetate gel [13].

- Transfer Time: Increase the transfer time. For rapid dry transfer systems, increasing time from 7 minutes to 8-10 minutes can dramatically improve detection [13].

- Gel Pre-treatment: If not using a Tris-acetate gel, equilibrating your gel in 20% ethanol for 5-10 minutes before transfer can enhance efficiency by removing salts and adjusting the gel to its final size [13].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Band Separation

Poor band separation, or resolution, is a common issue when working with HMW proteins. The table below outlines symptoms, causes, and solutions.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Smeared bands | Gel pore size too small; Protein aggregation [14] | Use lower % polyacrylamide or Tris-acetate gel; Ensure complete protein denaturation [13] [14] |

| Poor separation/compressed bands at top of gel | Incorrect gel chemistry for HMW proteins [13] | Switch from Tris-glycine to 3–8% Tris-acetate gels [13] |

| Bands not sharp or "smiling" | Gel overheating during electrophoresis [15] | Run gel at a lower voltage for a longer time; Use a cooling apparatus or run in a cold room [15] [14] |

| No separation, single broad band | Insufficient run time; Improper buffer [15] [14] | Increase electrophoresis time; Prepare fresh running buffer [15] [14] |

| High background after transfer | Incomplete transfer of HMW protein [13] | Increase transfer time (e.g., to 8-10 min for rapid dry transfer) [13] |

Optimizing Gel Selection: A Data-Driven Approach

Selecting the correct gel matrix is the most critical step for resolving HMW proteins. The following tables provide quantitative guidance for gel selection based on your protein's molecular weight.

Table 1: Polyacrylamide Gel Selection Guide for Protein Separation

| Gel Type | % Acrylamide | Optimal Separation Range for Proteins | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate | 3-8% | High Molecular Weight (HMW) Proteins (>150 kDa) [13] | Ideal for large proteins like EGFR (~190 kDa), HER2 (185 kDa), mTOR (289 kDa) [13] [16] |

| Bis-Tris / Tris-Glycine | 4-12% | Mid to High Molecular Weight Proteins (50 - 200 kDa) | Broad-range separation; not ideal for proteins >200 kDa [13] |

| Bis-Tris / Tris-Glycine | 8-16% | Low to Mid Molecular Weight Proteins (10 - 150 kDa) | Optimal for resolving smaller proteins [14] |

Table 2: Agarose vs. Polyacrylamide Gels for Macro-Molecule Separation

| Parameter | Agarose Gels | Polyacrylamide Gels (PAGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Use | Nucleic acid separation; Very large protein complexes [17] | Protein separation (SDS-PAGE); Low MW nucleic acids [17] [18] |

| Pore Size | Large pores (controlled by % agarose) [17] | Small, tunable pores (controlled by %T, %C) [14] |

| Optimal Protein Separation Range | Less common, but high-concentration gels (6-14%) can separate proteins in the 10-200 kDa range [17] | Standard method; effective across a wide range, from <10 kDa to >500 kDa with proper gel choice [13] [14] |

| Key Advantage for HMW Proteins | Very open matrix can be useful for extremely large complexes [17] | Tunable pore size and specialized chemistries (e.g., Tris-acetate) make it the preferred choice for HMW proteins [13] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Western Blotting of HMW Proteins Using Tris-Acetate Gels

This protocol is adapted from Thermo Fisher Scientific application notes for successful transfer of HMW proteins [13].

Materials:

- NuPAGE 3-8% Tris-Acetate Protein Gels [13]

- iBlot 2 Gel Transfer Device and Nitrocellulose Membranes [13]

- Tris-Acetate SDS Running Buffer (e.g., NuPAGE) [13]

- Fluorescent Blocking Buffer (e.g., Blocker FL) [13]

- Primary and fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies [13]

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Dilute protein samples in a denaturing loading buffer containing SDS and a reducing agent (e.g., DTT). Boil samples at 98°C for 5 minutes to ensure complete denaturation, then immediately place on ice [14].

- Gel Electrophoresis: Load samples and a prestained protein ladder onto the 3-8% Tris-acetate gel. Run the gel at 150 V for approximately 90 minutes or until the dye front reaches the bottom, using fresh running buffer. For best results, use a cooling system to prevent overheating [13] [14].

- Protein Transfer (Rapid Dry):

- Prepare the gel stack as per the iBlot 2 instructions.

- Critical Step: For proteins >150 kDa, set the transfer time to 8-10 minutes using the P0 or P3 program (20-25 V). Do not use the standard 7-minute program [13].

- Post-Transfer Analysis: Block the membrane for 30 minutes at room temperature. Probe with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, wash, and then incubate with fluorescent secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature before imaging [13].

Protocol 2: Ethanol Equilibration for Enhanced HMW Protein Transfer

If a Tris-acetate gel is not available, this pre-transfer step can significantly improve transfer efficiency from Bis-Tris gels [13].

Materials:

- Post-electrophoresis gel

- 20% Ethanol (v/v) in deionized water

Method:

- Following electrophoresis, carefully remove the gel from its cassette.

- Submerge the gel in 20% ethanol solution.

- Equilibrate for 5-10 minutes at room temperature on a gentle shaker.

- Proceed with standard wet or semi-dry transfer protocols. This step helps remove contaminating salts and adjusts the gel size, improving transfer efficiency for HMW proteins like KLH (~360-400 kDa) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function in HMW Protein Research |

|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate Gels (3-8%) | Provides an open pore matrix for optimal migration and separation of HMW proteins; superior to standard Tris-glycine gels [13]. |

| Low-ADS Membranes | Nitrocellulose or PVDF membranes with low non-specific binding, crucial for reducing background in sensitive immunoassays [19]. |

| Rapid Transfer Systems | Devices (e.g., iBlot 2) that enable fast, efficient transfer of large proteins with optimized protocols for HMW targets [13]. |

| High-Sensitivity Stains & Antibodies | Fluorescent stains and highly cross-adsorbed antibodies conjugated to bright dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor Plus 800) for detecting low-abundance HMW proteins [13]. |

| Photo-Active Hydrogels | Advanced hydrogels that can be photopatterned with pore-size gradients, enabling high-resolution separation of proteins across a broad mass range for single-cell western blotting [16]. |

| Fmoc-Ala-OH-13C3 | Fmoc-Ala-OH-13C3, MF:C18H17NO4, MW:314.31 g/mol |

| Penconazole-d7 | Penconazole-d7, MF:C13H15Cl2N3, MW:291.22 g/mol |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Gel Selection for Protein Separation

HMW Protein Western Blot Optimization

Fundamental Principles of Protein Migration and Transfer Efficiency

The study of high molecular weight (HMW) proteins (>150 kDa) presents unique challenges in protein research. Their large size affects behavior in analytical techniques from electrophoresis to chromatography. Understanding the fundamental principles governing their migration and transfer is essential for researchers in drug development aiming to accurately analyze these proteins, which include many critical therapeutic targets such as membrane receptors, structural proteins, and protein complexes.

This technical support center addresses the specific obstacles professionals encounter when working with HMW proteins, providing targeted troubleshooting guidance and optimized protocols to improve experimental outcomes and research resolution.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on HMW Protein Analysis

Q: Why do my high molecular weight proteins get stuck and fail to migrate properly in SDS-PAGE?

A: Poor migration of HMW proteins is a common issue with several potential causes and solutions [20]:

- Inappropriate Gel Pore Size: Gels with too small pore sizes physically obstruct large proteins.

- Incomplete Denaturation: If the protein sample is not fully denatured and reduced, residual secondary or tertiary structure can hinder migration.

- Sample Overloading: Excessively high protein concentration can cause aggregation at the top of the gel.

- DNA Contamination: Genomic DNA in cell lysates increases viscosity, leading to protein aggregation and aberrant migration.

- Solution: Shear genomic DNA by sonication or benzonase treatment before loading [21].

Q: How can I improve the transfer efficiency of HMW proteins onto a membrane for Western blotting?

A: Efficient transfer of proteins >150 kDa from gel to membrane requires specific optimization [2]:

- Increase Transfer Time: HMW proteins migrate more slowly and require extended transfer times. For rapid dry transfer systems (e.g., iBlot 2), increase time from the standard 7 minutes to 8-10 minutes [2].

- Optimize Transfer Buffer Composition: Adding a low concentration of SDS (0.01-0.05%) to the transfer buffer helps elute large proteins from the gel. However, higher SDS concentrations can inhibit protein binding to the membrane, so optimization is key [5].

- Gel Pre-equilibration: For gels other than Tris-acetate, incubate the gel in 20% ethanol for 5-10 minutes before transfer. This step removes buffer salts and can help shrink the gel, improving transfer efficiency for HMW targets [2].

- Methanol Concentration: Methanol in transfer buffer helps proteins bind to the membrane but can shrink the gel matrix and trap large proteins. For HMW proteins, a lower methanol concentration (e.g., 10%) is often beneficial [5].

Q: What causes high background or nonspecific bands when detecting my HMW protein?

A: This is frequently related to antibody or detection conditions [21]:

- High Antibody Concentration: Too high a concentration of primary or secondary antibody increases nonspecific binding.

- Solution: Titrate antibodies to find the optimal, lowest possible concentration.

- Insufficient Blocking: Inadequate blocking of nonspecific sites on the membrane leads to uniform background.

- Solution: Extend blocking time (≥1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4°C) and/or increase the concentration of blocking agent (e.g., BSA or casein). Including 0.05% Tween 20 in buffers can also help minimize background [21].

- Incompatible Blocking Buffer: The choice of blocker can be critical. For instance, when detecting phosphoproteins, avoid milk-based blockers as they contain phosphoproteins; use BSA instead [21].

Optimized Experimental Protocols for HMW Proteins

Protocol: Western Blotting for Proteins >150 kDa

This protocol is optimized for the transfer and detection of HMW proteins, based on recommendations from leading technical resources [2] [5].

1. Gel Electrophoresis:

- Gel Choice: Use a 3-8% Tris-acetate gel for optimal separation of HMW proteins. Avoid high-percentage Tris-glycine gels which compact HMW proteins at the top [2].

- Electrophoresis Conditions: Run gels according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ensure samples are fully reduced and denatured.

2. Pre-Transfer Gel Equilibration (for non-Tris-acetate gels):

- Submerge the gel in 20% ethanol (in deionized water) for 10 minutes with gentle agitation at room temperature [2].

3. Transfer Stack Assembly:

- Membrane: Use nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane, activated according to manufacturer's instructions.

- Buffer: For wet transfer systems, use standard Tris-glycine transfer buffer. To enhance HMW protein elution, pre-equilibrate the gel for 10 minutes in transfer buffer containing 0.02-0.04% SDS, then transfer using buffer containing 0.01% SDS [5].

- Assembly: Ensure perfect contact between gel and membrane by rolling a glass pipette over the stack to remove all air bubbles [5].

4. Transfer:

- Method: Wet, semi-dry, or rapid dry transfer can be used.

- Conditions:

5. Post-Transfer Validation:

- Stain the gel with a total protein stain (e.g., Coomassie Blue) post-transfer to confirm the HMW protein has been successfully eluted [21].

- Alternatively, stain the membrane with a reversible protein stain to confirm presence and position of the target protein [21].

Workflow Diagram: HMW Protein Western Blot Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the critical decision points and optimization path for successful Western blotting of high molecular weight proteins.

Quantitative Data for HMW Protein Analysis

Recommended Transfer Parameters for HMW Proteins (>150 kDa)

The following table summarizes optimized transfer parameters based on the transfer system used [2].

| Transfer System | Method/Program | Voltage | Run Time | Key Buffer Additives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Dry Transfer (e.g., iBlot 2) | P0, P3 | 20-25 V | 8-10 min | Optional: 0.01% SDS for difficult transfers |

| Rapid Semi-Dry Transfer (e.g., Power Blotter) | Standard method | System default | 10-12 min | 1-Step Transfer Buffer |

| Standard Wet Transfer | Standard protocol | Standard voltage | 25-50% longer than standard | 0.01-0.02% SDS, 10% Methanol |

Troubleshooting Common Electrophoresis and Transfer Issues

This table connects common problems observed during HMW protein work with their likely causes and direct solutions [20] [21] [5].

| Observed Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins stuck in gel | Inappropriate gel pore size | Switch to 3-8% Tris-acetate or low-% Bis-Tris gel [2] [20] |

| Poor transfer efficiency | Insufficient transfer time or voltage | Increase transfer time by 25-50%; add 0.01-0.02% SDS to transfer buffer [2] [5] |

| High background on blot | Inadequate blocking or high antibody concentration | Optimize blocking time/temperature; titrate down antibody concentration [21] |

| Vertical streaking in lanes | Overloaded protein or DNA contamination | Reduce protein load; shear genomic DNA [20] [21] |

| Diffuse or nonspecific bands | Antibody cross-reactivity | Include appropriate controls; validate antibody specificity; try different antibody [21] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials critical for successful HMW protein analysis, along with their specific functions in the experimental workflow.

| Reagent/Material | Function in HMW Protein Work | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate Gels (3-8%) | Provides larger pore size for better separation and transfer of HMW proteins [2]. | Superior to Bis-Tris and Tris-glycine gels for proteins >150 kDa [2]. |

| Nitrocellulose/PVDF Membrane | Immobilizes proteins after transfer for antibody probing [2] [5]. | Standard pore size 0.45 µm; use 0.2 µm for proteins <10 kDa [5]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent that denatures proteins and confers negative charge [5]. | Add 0.01-0.05% to transfer buffer to aid HMW protein elution [5]. |

| Methanol | Promotes protein binding to membrane but can shrink gel pores [5]. | Use at 10-20% concentration in transfer buffer; optimize for specific protein [5]. |

| Ethanol (20%) | Pre-equilibration solution for gels prior to transfer [2]. | Removes salts and prevents increased conductivity/heat during transfer [2]. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Ion-pairing reagent for reversed-phase LC separations of proteins/peptides [22]. | Typically used at 0.1% in water and acetonitrile for LC-MS applications [22]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents protein degradation during sample preparation [23]. | Use EDTA-free versions for mass spectrometry; include PMSF [23]. |

| Sodium 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate-13C4,d3 | Sodium 3-methyl-2-oxobutanoate-13C4,d3, MF:C5H7NaO3, MW:145.086 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Boc-L-Ala-OH-2-13C | Boc-L-Ala-OH-2-13C, MF:C8H15NO4, MW:190.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Optimized Protocols for Separation, Transfer, and Detection

For researchers focused on high molecular weight (HMW) proteins, selecting the appropriate gel chemistry is a critical determinant of experimental success. The separation of complex protein mixtures by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) relies on the precise interplay between buffer systems, pH conditions, and gel matrix properties [24]. While SDS-PAGE is a foundational laboratory technique, not all gel chemistries perform equally, particularly when resolving proteins above 100 kDa. The standard Tris-Glycine system, though widely used, presents significant limitations for HMW protein analysis, often resulting in compressed bands, poor resolution, and inefficient transfer to membranes [25]. These technical challenges can obstruct accurate molecular weight determination and downstream analysis, ultimately compromising research outcomes in proteomic studies and drug development pipelines.

Advances in gel chemistry have yielded specialized buffer systems designed to overcome these limitations. Tris-Acetate and Bis-Tris gels offer sophisticated alternatives to traditional Tris-Glycine systems, each with distinct operational pH ranges, buffering capacities, and separation characteristics [24] [25] [26]. Understanding the mechanistic basis for these differences enables researchers to make informed decisions that enhance resolution, preserve protein integrity, and improve transfer efficiency for Western blotting and other detection methods. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these three major gel systems, with particular emphasis on optimizing conditions for HMW protein research.

Technical Comparison of Gel Buffer Systems

The optimal separation of proteins by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis depends significantly on the buffer system's pH and ionic composition. These factors influence protein charge, migration rate, and the stability of the proteins during electrophoresis. The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three primary gel chemistries.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Gel Buffer Systems for Protein Electrophoresis

| Characteristic | Tris-Glycine | Bis-Tris | Tris-Acetate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Operating pH | ~8.6 (alkaline) [27] | ~6.4 (slightly acidic) [26] | ~7.0 (neutral) [25] [27] |

| Key Buffering Ion | Glycine [24] | Bis-Tris [26] | Acetate [25] |

| Optimal Protein Separation Range | Broad range [25] | Low to medium molecular weight [26] | High molecular weight (30-500 kDa) [25] |

| Primary Advantage | General-purpose, widely available | Sharp bands, low background staining [26] | * Superior resolution & transfer of HMW proteins* [25] [28] |

| Primary Disadvantage | Poor resolution of HMW proteins; alkaline pH can damage proteins [25] | Chelates metal ions [26] | More specialized and often more expensive |

| Recommended Running Buffer | Tris-Glycine-SDS [24] | MES (for ≤50 kDa) or MOPS (for ≥50 kDa) [26] | Tris-Acetate-SDS [25] |

Mechanism of Electrophoretic Separation

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the most appropriate gel system based on protein size and experimental goals.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Tris-Acetate SDS-PAGE for High Molecular Weight Proteins

The Tris-Acetate system is specifically designed for superior resolution of high molecular weight proteins (30-500 kDa) [25]. The protocol below is adapted for pre-cast gels to ensure reproducibility.

Sample Preparation:

- Dilute your protein sample with NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer [25]. The use of LDS (Lithium Dodecyl Sulfate) over traditional SDS is recommended as it maintains a pH >7.0 during denaturation, minimizing acid-induced cleavage of Asp-Pro bonds and preserving protein integrity [25].

- If reduction is required, add a reducing agent (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) to the sample buffer.

- Heat the samples at 70°C for 10 minutes to denature the proteins. Avoid higher temperatures (e.g., 100°C) to prevent excessive protein degradation [25].

Electrophoresis Setup:

- Use a 3-8% or 7% Tris-Acetate precast gel [25] [29]. The low-percentage polyacrylamide creates larger pores, facilitating the entry and migration of large proteins.

- Prepare 1X NuPAGE Tris-Acetate SDS Running Buffer from the 20X concentrate according to the manufacturer's instructions [25].

- For improved band sharpness, especially when analyzing reduced proteins, add 500 µL of NuPAGE Antioxidant to the chamber of the running buffer that corresponds to the upper portion of the gel (cathode) [25]. This minimizes reoxidation of cysteine residues during the run.

- Load samples and appropriate protein standards (e.g., HiMark Prestained Protein Standard) into the wells.

Electrophoresis Run:

- Run the gel at a constant voltage of 150 V for approximately 60 minutes (for mini-gel format) or until the dye front has migrated to the bottom of the gel.

- Following electrophoresis, proceed to Western transfer or gel staining.

Bis-Tris SDS-PAGE for Low to Medium Molecular Weight Proteins

Bis-Tris gels, with their slightly acidic pH, are ideal for achieving sharp bands and high resolution for proteins under 100 kDa [26]. The following protocol is for casting and running hand-cast Bis-Tris gels.

Gel Casting:

- Resolving Gel (15 mL for a mini-gel): Combine the following components in the order listed for a 12% resolving gel:

- Acrylamide (30% stock): 6.0 mL

- 1.0 M Bis-Tris (pH 6.4): 3.75 mL [26]

- Water: 5.02 mL

- 10% SDS: 150 µL

- 10% APS: 75 µL

- TEMED: 7.5 µL Mix and pour immediately, overlaying with isopropanol or water to ensure a flat surface. Allow to polymerize completely (~15-30 minutes).

- Stacking Gel (15 mL for a mini-gel): After removing the overlay, pour the stacking gel on top of the polymerized resolving gel:

- Acrylamide (30% stock): 1.98 mL

- 0.5 M Tris (pH 6.8): 3.78 mL [26]

- Water: 9 mL

- 10% SDS: 150 µL

- 10% APS: 75 µL

- TEMED: 15 µL Insert the gel comb without introducing bubbles. Allow to polymerize.

Sample Preparation and Electrophoresis:

- Prepare protein samples in a standard Laemmli-style sample buffer or a compatible LDS buffer.

- Denature samples by heating at 70-95°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Prepare the 5x Running Buffer [26]:

- For proteins ≤50 kDa: Use MES Buffer (250 mM Tris, 250 mM MES, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS).

- For proteins ≥50 kDa: Use MOPS Buffer (250 mM Tris, 250 mM MOPS, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS).

- Load samples and run the gel at a constant voltage of 150-200 V until the dye front reaches the bottom.

Western Blot Transfer for High Molecular Weight Proteins

Transferring HMW proteins from the gel to a membrane is a common bottleneck. The Tris-Acetate system significantly improves transfer efficiency.

Procedure:

- Following SDS-PAGE, equilibrate the gel in NuPAGE Transfer Buffer for 5-10 minutes [25].

- Prepare the transfer stack in the following order (cathode to anode):

- Sponge / Filter Paper

- Gel

- PVDF or Nitrocellulose Membrane (activated in methanol if using PVDF)

- Filter Paper / Sponge

- Place the cassette into the transfer apparatus filled with the Transfer Buffer.

- For HMW proteins, use a low-voltage (e.g., 25 V overnight) or low-current protocol to facilitate the slow, complete movement of large proteins out of the gel matrix. The lower polyacrylamide concentration at the top of Tris-Acetate gradient gels is particularly beneficial for this process [25].

- After transfer, proceed with standard immunodetection protocols.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My high molecular weight protein (200 kDa) appears as a smeared band near the top of a Tris-Glycine gel. What should I do? A: This compression is a classic limitation of Tris-Glycine gels for HMW proteins [25]. Switch to a Tris-Acetate gel (e.g., 3-8% gradient). The near-neutral pH and acetate ions provide a more effective driving force for large proteins, resulting in better separation and sharper bands [25] [28].

Q2: Why are my protein bands blurry or smeary in a Bis-Tris gel, even for medium-sized proteins? A: Blurry bands can result from several factors. Ensure your sample is fully denatured by heating in the presence of SDS and a reducing agent. Additionally, verify that you are using the correct running buffer—MES for proteins ≤50 kDa and MOPS for proteins ≥50 kDa [26]. Using the wrong buffer can lead to poor resolution.

Q3: I am studying a multimeric protein complex in its native state. Which gel system should I use? A: For native PAGE (non-denaturing conditions), both Tris-Acetate and Bis-Tris systems are suitable as they can be run without SDS [25] [26]. Your choice may depend on the stability of your complex at different pH levels. The neutral pH of Tris-Acetate or the slightly acidic pH of Bis-Tris can help maintain protein integrity and activity better than the alkaline pH of Tris-Glycine [24] [25].

Q4: How does the pH of the gel system affect my protein samples? A: pH is critical for protein stability. The alkaline pH (~8.6) of traditional Tris-Glycine systems can promote protein degradation, including cleavage of sensitive peptide bonds like Asp-Pro [25]. The near-neutral pH of Tris-Acetate (~7.0) and slightly acidic pH of Bis-Tris (~6.4) are milder, helping to preserve protein integrity and minimize artifacts, which is crucial for accurate analysis [25] [26].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Protein Gel Electrophoresis

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Resolution of HMW Proteins | Wrong gel chemistry (Tris-Glycine); Gel percentage too high [25]. | Switch to a low-percentage Tris-Acetate gel (e.g., 3-8%) [25]. |

| Smeared Bands | Incomplete denaturation; Protein aggregation; Incorrect running buffer [27] [26]. | Ensure complete sample denaturation (heat with SDS/reductant). Use the correct running buffer (MES/MOPS for Bis-Tris) [26]. |

| Poor Transfer of HMW Proteins | Proteins are trapped in the gel matrix [25]. | Use a Tris-Acetate gel for easier protein elution. Extend transfer time and use low voltage [25]. |

| Protein Degradation (Extra Bands) | Asp-Pro cleavage due to acidic pH during heating; Proteolysis [25]. | Use NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (maintains pH >7.0) instead of traditional Laemmli buffer [25]. Keep samples on ice. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful protein analysis relies on a suite of optimized reagents. The table below lists key materials for experiments focused on HMW proteins.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High Molecular Weight Protein Research

| Item | Function | Recommendation for HMW Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Precast Gels | Provides a ready-to-use, consistent separation matrix. | NuPAGE Tris-Acetate Gels (3-8% or 7%) for optimal HMW resolution and transfer [25]. |

| Sample Buffer | Denatures proteins and confers negative charge. | NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer: Maintains pH >7.0 during heating, minimizing protein degradation [25]. |

| Running Buffer | Conducts current and establishes ion fronts for separation. | NuPAGE Tris-Acetate SDS Running Buffer: Matched to the Tris-Acetate gel chemistry [25]. |

| Antioxidant | Prevents re-oxidation of cysteine residues during electrophoresis. | NuPAGE Antioxidant: Add to running buffer for sharper, well-defined bands of reduced proteins [25]. |

| Transfer Buffer | Medium for electrophoretic protein transfer to membranes. | NuPAGE Transfer Buffer: Formulated for efficient transfer, particularly of large proteins [25]. |

| Protein Ladder | Provides molecular weight standards for size estimation. | HiMark Prestained Protein Standard: A wide-range ladder ideal for monitoring HMW protein separation [25]. |

| N-Methylformamide-d5 | N-Methylformamide-d5, CAS:863653-47-8, MF:C2H5NO, MW:64.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ethambutol-d8 | Ethambutol-d8, CAS:1129526-23-3, MF:C10H24N2O2, MW:212.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization for HMW Protein Analysis

The following diagram summarizes the integrated workflow for analyzing high molecular weight proteins, from sample preparation to detection, highlighting the critical role of gel chemistry selection.

Advanced Western Blotting Techniques for Proteins >150 kDa

Troubleshooting Common Issues with High Molecular Weight Proteins

Q1: Why is the transfer of my high molecular weight protein (>150 kDa) inefficient?

Inefficient transfer is one of the most common challenges with large proteins. The solutions involve optimizing your transfer buffer and conditions [30] [5].

- Add SDS to Transfer Buffer: Include 0.01-0.05% SDS in your transfer buffer to help elute large proteins from the gel. However, note that excessive SDS can inhibit protein binding to the membrane [5].

- Optimize Methanol Concentration: Use a methanol concentration at 10-20%. Methanol helps proteins bind to the membrane but can shrink the gel pores, hindering the exit of large proteins. A lower percentage (e.g., 10%) can facilitate transfer [5].

- Adjust Transfer Time and Mode: For proteins >150 kDa, consider extending the transfer time. A wet transfer at 110 V for 150 minutes is recommended over semi-dry methods for more consistent results [30].

- Pre-equilibrate the Gel: Before transfer, equilibrate the gel in transfer buffer containing 0.02-0.04% SDS for 10 minutes to promote protein elution [5].

Q2: How can I avoid high background, especially when detecting phosphorylated proteins?

High background often stems from non-specific antibody binding or contaminated reagents [30].

- Choose the Correct Blocking Buffer: For phosphorylated proteins, do not use non-fat dry milk as it contains phosphorylatable proteins that cause high background. Instead, use 1% BSA in TBST [30].

- Optimize Wash Stringency and Time: Ensure thorough washing after antibody incubations. Perform 4-6 washes for 5 minutes each with agitation. Insufficient washing leaves unbound antibody, while excessive washing can weaken the signal [30] [31].

- Filter Antibodies: Centrifuge antibody solutions before use to remove protein aggregates that can cause "splotchy" or uneven backgrounds [30].

- Check for Contamination: Inspect all buffers for bacterial contamination, which can cause "patchy" spots across the blot [30].

Q3: Why do I see a weak or absent signal for my target protein?

A weak signal can be due to several factors, from sample integrity to antibody conditions [30].

- Verify Sample Freshness: Prepare fresh samples and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles, as protein degradation can diminish signal [30].

- Titrate Your Primary Antibody: A titration experiment (e.g., testing concentrations from 0.2 to 5.0 µg/mL) is crucial to find the optimal signal-to-noise ratio [30].

- Confirm Antibody Reactivity: Ensure the antibody is validated for the species of your sample and that your sample type expresses the target protein.

- Use a Positive Control: Always include a recommended positive control lysate to confirm that your antibody and protocol are functioning correctly [30].

Q4: Why is the actual band size different from the predicted size?

Observing a band that does not match the predicted molecular weight is frequent and can have biological causes [30].

- Post-Translational Modifications: Phosphorylation, glycosylation, and other modifications add mass to the protein, resulting in a higher apparent molecular weight [30].

- Splice Variants and Isoforms: The gene may produce multiple protein products of different sizes, which can be tissue or condition-specific [30].

- Protein Multimerization: Non-reduced complexes like dimers can form, appearing as high molecular weight bands. Ensure your sample buffer is fresh and contains adequate reducing agents (e.g., DTT or β-mercaptoethanol) [30].

Optimized Protocols for Proteins >150 kDa

Sample Preparation and Gel Electrophoresis

Efficient sample preparation is the foundation of a successful western blot. For tissues, use a combination of mechanical homogenization (e.g., Dounce homogenizer) and sonication on ice to fully disrupt cells and release target proteins [32]. A suitable lysis buffer (e.g., RIPA) with 100-150 mM NaCl can prevent aggregation, and reducing agents are essential [32]. When separating proteins by size, use low-percentage gels to maximize resolution [30]:

| Protein Size (kDa) | Acrylamide Gel Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| < 80 | 13 |

| > 80 | 7.5 |

For proteins >150 kDa, a gel percentage of 6-8% is ideal. Load 50 µg of whole cell lysate per lane as a starting point [30].

Protein Transfer and Immunodetection

The following workflow outlines the key steps for an optimized western blot, with critical adjustments for high molecular weight proteins highlighted in the transfer phase.

Critical Transfer Protocol Adjustments:

After assembling the transfer sandwich, execute the transfer with the following optimized conditions [30] [5]:

- Transfer Buffer: Use standard Tris-Glycine buffer supplemented with 0.05% SDS and 20% methanol [30].

- Transfer Conditions: Perform a wet transfer for 150 minutes at 110 V. Alternatively, a constant current of 1 Amp for 1 hour can be used [30].

- Membrane Choice: Use a 0.2 µm pore size nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane. The smaller pore size provides better retention of large proteins. For PVDF, remember to pre-wet it in 100% methanol for 30 seconds before equilibration in transfer buffer [31] [5].

Immunodetection Protocol:

- Blocking: Incubate the membrane in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST for 30-60 minutes at room temperature with agitation. For phosphorylated proteins, use 1% BSA in TBST instead [30] [31].

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the primary antibody in blocking buffer. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 2-8°C with agitation. Use the volume recommended by the manufacturer to ensure full membrane coverage [31].

- Washing: Wash the membrane 3 times for 10 minutes each with ample TBST [31].

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Dilute the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in wash buffer. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature with agitation. Protect from light if using fluorescent labels [31].

- Final Washing: Wash the membrane 6 times for 5 minutes each with TBST to thoroughly remove unbound antibody [31].

- Detection: Incubate with a high-sensitivity chemiluminescent substrate (e.g., SuperSignal West Femto) for approximately 5 minutes before imaging [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and their specific functions when working with high molecular weight proteins.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Low-Percentage Acrylamide Gels (6-8%) | Creates larger pores for better separation and migration of high molecular weight proteins during electrophoresis [30]. |

| 0.2 µm Pore Size Membrane | Provides superior retention of large proteins compared to standard 0.45 µm membranes, preventing pass-through [5]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Added to the transfer buffer (0.01-0.05%) to coat proteins with negative charge and facilitate their elution from the gel matrix [30] [5]. |

| Methanol | Used in transfer buffer (10-20%) to promote protein binding to the membrane; lower concentrations can improve transfer efficiency for large proteins [5]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A preferred blocking agent for phosphorylated targets, as it does not contain phosphoproteins that cause high background like non-fat dry milk [30]. |

| High-Sensitivity Chemiluminescent Substrate | Essential for detecting low-abundance large proteins. Substrates like SuperSignal West Femto provide the necessary signal amplification [31]. |

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | A reducing agent used in lysis and sample buffers to break disulfide bonds and ensure proteins are fully denatured and linearized [32]. |

| Vemurafenib-d7 | Vemurafenib-d7, CAS:1365986-73-7, MF:C23H18ClF2N3O3S, MW:497.0 g/mol |

| Ro-15-2041 | Ro-15-2041, CAS:77448-87-4, MF:C12H12BrN3O, MW:294.15 g/mol |

Buffer System Optimization for Enhanced Resolution

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

What are the primary challenges when working with high molecular weight (HMW) proteins in western blotting?

The main challenges involve inefficient transfer from the gel to the membrane and poor separation during electrophoresis [33].

HMW proteins (>150 kDa) migrate slowly through the polyacrylamide gel matrix and often do not transfer completely compared to mid- to low-molecular-weight proteins. This can result in weak, diffuse, or absent signals on the final blot [5] [33] [34]. Standard protocols, particularly the use of popular 4-20% Tris-glycine gradient gels, often compact HMW proteins into a narrow region at the top of the gel, leading to poor resolution and subsequent transfer difficulties [2].

How can I optimize my gel system for better HMW protein separation?

Optimizing your gel system is a critical first step. The key is to use a gel with a more open pore structure to allow large proteins to migrate effectively.

- Use Low-Percentage or Specialized Gels: Low-percentage Bis-Tris or Tris-glycine gels are recommended. However, for the best separation of HMW proteins, 3–8% Tris-acetate gels are superior. The Tris-acetate buffer system, with its higher pH (around 7–8), provides a more open matrix, allowing HMW proteins to migrate farther and resolve better than in Tris-glycine systems [2].

- Consider a Versatile Buffer System: For a broad molecular weight range (6-200 kDa), a multiphasic buffer system using taurine and chloride as trailing and leading ions, respectively, with Tris as the buffering ion, can provide high-resolution stacking and destacking of proteins [35].

The table below summarizes the key differences in gel performance:

| Gel Type | Recommended Use | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| 3-8% Tris-Acetate | Optimal for HMW proteins (>150 kDa) | Open matrix for superior HMW protein separation and transfer [2]. |

| Low % Bis-Tris or Tris-Glycine | Can be used for HMW proteins | Better than high-percentage gels, but not ideal [2]. |

| 4-20% Tris-Glycine Gradient | Broad range for proteins 20-200 kDa | Poor for proteins >200 kDa; compacts them at the gel top [2]. |

| Multiphasic Taurine-Chloride System | Broad range (6-200 kDa) | Tailored resolution with minimal issues for post-electrophoretic identification [35]. |

What transfer conditions should I use for HMW proteins?

Efficient transfer is paramount. The general principle is to facilitate the movement of large proteins out of the gel and ensure they bind to the membrane.

- Increase Transfer Time: HMW proteins migrate more slowly and require more time to elute from the gel. For wet transfer systems, increase the transfer time to 3–4 hours [34]. For rapid dry transfer systems, increasing the time from a standard 7 minutes to 8–10 minutes can significantly improve detection [2].

- Optimize Transfer Buffer Additives:

- SDS: Adding a small amount of SDS (0.01-0.02%) to the transfer buffer can help elute HMW proteins from the gel by maintaining a negative charge [5] [34]. A pre-transfer gel equilibration in buffer containing 0.02–0.04% SDS is also recommended [5].

- Methanol: Methanol improves protein binding to the membrane but can shrink the gel pores, hindering HMW protein elution. For HMW proteins, decrease the methanol concentration to 5-10% to improve transfer efficiency [5] [34].

- Use the Correct Membrane Pore Size: While 0.45 µm membranes are standard, a 0.2 µm pore size membrane is recommended for better retention of all proteins and can be particularly helpful for ensuring HMW proteins do not pass through the membrane [5].

Why do I see smearing or poor resolution for my HMW protein?

Smearing can result from several factors, from incomplete separation to overheating.

- Incomplete Transfer: The protein may be partially stuck in the gel. Review and apply the transfer optimizations listed above.

- Overheating During Electrophoresis: High voltages can cause overheating, leading to protein degradation and smearing. Run gels at lower voltages or use ice packs and a cooling system to keep the apparatus cool [33] [34].

- Sample Overload: Loading too much protein can overwhelm the gel's resolving capacity, leading to broad or smeared bands. Decrease the total protein load per lane [5] [34].

- Protein Aggregation: HMW proteins are prone to aggregation. Ensure your sample buffer is fresh, and thoroughly denature the samples by heating at 70-100°C before loading [36].

I have optimized my transfer, but the signal is still weak. What else can I check?

If transfer is confirmed, the issue may lie with detection.

- Antibody Incubation Conditions: Ensure you are using the recommended dilution buffer (BSA or non-fat dry milk) specified on the antibody datasheet. Using the wrong buffer can severely compromise sensitivity [34].

- Antibody Sensitivity: Verify that your primary antibody is sensitive enough to detect the protein at endogenous levels and is reactive for your species. Some antibodies are validated only for overexpression systems [34].

- Membrane Blocking and Washing: Ensure the membrane is fully blocked to prevent nonspecific antibody binding and high background. The composition of your blocking and washing buffers (e.g., using TBS over PBS) can also affect signal intensity [34].

Experimental Workflow for HMW Protein Analysis

The following diagram outlines the key decision points and optimization steps for successful analysis of high molecular weight proteins.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for optimizing HMW protein western blotting.

| Reagent / Material | Function in HMW Protein Workflow |

|---|---|

| Tris-Acetate Gels (3-8%) | Provides an open-pore matrix for superior separation and transfer of large proteins [2]. |

| PVDF Membrane | Hydrophobic membrane with high protein binding capacity; requires activation in methanol before use [33]. |

| Transfer Buffer with SDS | Small amounts of SDS (0.01-0.04%) help elute HMW proteins from the gel during transfer [5] [34]. |

| Methanol | Added to transfer buffer to promote protein binding to the membrane; concentration should be reduced (5-10%) for HMW targets [5] [33]. |

| Taurine-Chloride Buffer System | A versatile multiphasic buffer system for high-resolution separation of a wide molecular weight range [35]. |

| Pre-stained Protein Ladder | Allows visual monitoring of electrophoresis progression and transfer efficiency [5]. |

For researchers focused on improving the resolution of high molecular weight (HMW) proteins, selecting the appropriate electroblotting membrane is a critical experimental design choice that directly impacts data quality and reproducibility. The transfer membrane serves as the foundational platform for immobilizing proteins after gel electrophoresis, enabling subsequent antibody probing and detection. Within the context of advanced protein research, the debate between Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) and Nitrocellulose (NC) membranes is particularly consequential for the study of HMW targets (>100 kDa), where transfer efficiency and binding retention are often challenging. This technical support center guide provides targeted troubleshooting and validated protocols to optimize the retention and detection of HMW proteins, directly supporting rigorous scientific inquiry in drug development and basic research.

Comparative Membrane Analysis: PVDF vs. Nitrocellulose

The following tables summarize key quantitative and qualitative differences between PVDF and nitrocellulose membranes, providing an at-a-glance reference for informed selection.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties and Performance Metrics

| Property | PVDF | Nitrocellulose (NC) |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Binding Capacity [37] [38] | 150–300 µg/cm² | 80–100 µg/cm² |

| Best Suited For Protein Size [38] [37] | High molecular weight (HMW) proteins | Mid-to-low molecular weight proteins |

| Binding Mechanism [39] [37] | Hydrophobic interactions | Nitrogen dipole, H-bond, ionic, and hydrophobic |

| Durability & Chemical Resistance [38] [37] | High; withstands stripping and harsh stains | Low; fragile and brittle when dry |

| Pre-wetting Requirement [39] [37] | Requires activation in 100% methanol or ethanol | Ready to use; requires methanol in transfer buffer |

Table 2: Suitability for Detection Methods and Applications

| Application | PVDF | Low Fluorescence PVDF | Nitrocellulose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemiluminescent Detection [39] | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Fluorescent Detection [39] | + | +++ | ++ |

| Stripping & Re-probing [38] [37] | Excellent - high durability and protein retention | Excellent | Not recommended - prone to signal loss |

| Total Protein Normalization [39] | + | +++ | ++ |

Experimental Protocols for High Molecular Weight Protein Transfer

Inefficient transfer and poor retention of HMW proteins are common challenges. The protocols below are specifically designed to address the unique requirements of large proteins.

Protocol 1: Optimized Wet Transfer for HMW Proteins (>100 kDa)

This protocol is adapted from standard wet tank transfer procedures with critical modifications to facilitate the elution of large proteins from the gel and their subsequent binding to the membrane [5] [40].

Reagents and Materials:

- Transfer Buffer (1X): 25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine. For HMW proteins, reduce methanol to 5-10% [40] [41].

- Pre-equilibration Buffer (2X): 2X Transfer buffer (without methanol) containing 0.02-0.04% SDS [5].

- PVDF membrane (0.2 µm or 0.45 µm pore size)

- Methanol (100%, analytical grade)

Methodology:

- Gel Pre-equilibration: Following electrophoresis, pre-equilibrate the polyacrylamide gel in Pre-equilibration Buffer for 10 minutes with gentle agitation. This step introduces a minimal amount of SDS to help dissociate the large protein complexes and promote their elution from the gel matrix [5].

- Membrane Activation: Immerse the PVDF membrane in 100% methanol for 30 seconds to 3 minutes to wet the hydrophobic surface. Rinse briefly with deionized water, then soak in 1X Transfer Buffer until ready for use [39] [37].

- Assemble Transfer Sandwich: Assemble the blot stack in the correct order, ensuring no air bubbles are trapped between the gel and membrane. Roll a glass tube or pipette over the surface to ensure perfect contact [5].

- Electrophoretic Transfer: Perform the transfer in a tank system filled with 1X Transfer Buffer (with reduced methanol and 0.01% SDS) at 4°C to dissipate heat. For HMW proteins, increase transfer time is critical. We recommend 3-4 hours at 70V (200-250mA) or an overnight transfer at lower constant current for optimal results [40] [41].

Protocol 2: Membrane Fixation for Enhanced Protein Retention (For Immunoblotting)

A recent study demonstrates that a post-transfer fixation step can significantly improve the binding of proteins, especially glycoproteins, to the membrane, thereby increasing detection sensitivity [42].

Reagents:

- Acetone (pre-chilled to 0°C)

- Methanol (for NC membrane protocol)

- Heating block or oven

Methodology for PVDF Membrane [42]:

- Immediately after protein transfer, immerse the PVDF membrane in 0°C acetone for 30 minutes.

- Subsequently, heat the membrane at 50°C for 30 minutes.

- Proceed with standard blocking and immunoblotting steps.

Methodology for Nitrocellulose Membrane [42]:

- After transfer, immerse the NC membrane in a 50% methanol/water mixture at 0°C for 30 minutes.

- Subsequently, heat the membrane at 50°C for 30 minutes.

- Proceed with standard blocking and immunoblotting steps.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Common Problems with HMW Proteins

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for High Molecular Weight Protein Blotting

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal for HMW Protein | Protein trapped in gel due to poor elution. | Pre-equilibrate gel with 0.02-0.04% SDS [5]. Reduce methanol in transfer buffer to 5-10% to prevent gel shrinkage and protein precipitation [40] [41]. |

| Incomplete transfer. | Significantly increase transfer time (e.g., 3-4 hours to overnight) [41]. Use a lower percentage gel to improve protein migration [5]. | |

| Signal Fading During Processing | Proteins washing off the membrane during blocking or washing. | Use a PVDF membrane for its superior protein retention [37]. Ensure a 0.2 µm pore size for better physical entrapment of proteins [5]. |

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding. | Optimize blocking conditions. For PVDF, use 5% BSA as a blocking agent, as non-fat dry milk can be too stringent for some antibodies [40]. |

| Swirling or Diffuse Bands | Poor contact between gel and membrane. | Ensure all air bubbles are removed when assembling the blot sandwich by rolling a glass pipette over each layer [5]. Check that blotting pads are saturated and resilient. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: For HMW protein research where I may need to re-probe the blot with multiple antibodies, which membrane is superior? A1: PVDF is unequivocally the better choice. Its high physical durability and chemical resistance allow it to withstand the harsh stripping conditions (e.g., low pH, detergents) required for antibody removal without degrading. Its high protein-binding capacity also ensures that your HMW target proteins remain immobilized on the membrane through multiple rounds of stripping and re-probing [38] [37].

Q2: How does pore size (0.2 µm vs. 0.45 µm) influence HMW protein detection? A2: For HMW proteins, both 0.2 µm and 0.45 µm pore sizes are commonly used and effective. The 0.45 µm pore size is standard for most HMW applications and can result in lower background. However, the 0.2 µm pore size offers a larger binding surface area and superior protein retention, which can be beneficial for low-abundance HMW targets or protocols involving multiple wash and stripping steps, as it minimizes protein loss [5] [37].

Q3: My HMW protein is not transferring efficiently even with extended time. What buffer modifications can help? A3: The key is to balance elution from the gel with binding to the membrane.

- Add SDS: Introduce a low concentration of SDS (0.01-0.02%) to the transfer buffer to help solubilize and pull large proteins out of the gel [5] [40].

- Reduce Methanol: Lower the methanol concentration from a standard 20% to 5-10%. Methanol promotes protein binding to the membrane but can cause precipitation and trapping of HMW proteins within the shrunken gel pores [40] [41].

Q4: How should I store my membrane after transfer if I cannot proceed to immunodetection immediately? A4: For both PVDF and nitrocellulose, the best practice is to:

- Rinse the membrane briefly in distilled water to remove residual buffer salts.

- Allow the membrane to air dry completely on filter paper.

- Store the dried membrane flat at room temperature. When ready to use, re-activate a dried PVDF membrane in methanol before blocking. Nitrocellulose does not require re-activation but should be wetted in buffer [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for HMW Protein Western Blotting

| Item | Function & Importance | Recommendation for HMW Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| PVDF Membrane | Solid support for protein immobilization. | Preferred over NC for superior HMW binding capacity and durability for re-probing [38] [37]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | Anionic detergent. | Critically added (0.02-0.04%) to gel pre-equilibration and (0.01%) to transfer buffer to facilitate HMW protein elution [5]. |

| Methanol | Polar solvent. | Required for PVDF activation. Concentration in transfer buffer should be optimized (5-10% for HMW proteins) to balance gel pore size and protein binding [5] [41]. |

| Ponceau S Stain | Reversible dye for total protein staining. | Used for quick visual confirmation of successful and uniform protein transfer immediately after blotting [41]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Prevents protein degradation. | Essential in lysis buffers to prevent cleavage of HMW proteins, which are often more susceptible to proteolysis [40]. |

| Exatecan Intermediate 7 | Exatecan Intermediate 7, MF:C13H13FN2O3, MW:264.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-type calcium channel blocker-1 | N-type calcium channel blocker-1, MF:C31H47N3, MW:461.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and optimizing a membrane and transfer protocol for high molecular weight protein research.

FAQs: Enhancing Resolution for High Molecular Weight Proteins

FAQ 1: What are the primary factors limiting resolution in SSNMR of high molecular weight proteins, and how can they be overcome?

In solid-state NMR (SSNMR), resolution for high molecular weight proteins is primarily constrained by instrumentation rather than molecular tumbling, making it well-suited for studying large complexes. The key limiting factors are magnetic field drift and couplings among nuclear spins. To achieve ultrahigh resolution, these challenges are addressed by using an external 2H lock to compensate for magnetic field drift and long-observation-window band-selective homonuclear decoupling (LOW-BASHD) to suppress 13C homonuclear couplings. This combined approach has enabled resolutions better than 0.2 parts per million (ppm) for proteins as large as 144 kilodalton [43] [44].

FAQ 2: Why are gigahertz-class NMR spectrometers particularly beneficial for SSNMR studies of large proteins?

Ultrahigh field (UHF), gigahertz-class NMR spectrometers (e.g., 1.1 GHz and 1.2 GHz) offer superior resolution and sensitivity. For SSNMR, resolution improves continuously with increasing magnetic field strength, unlike solution NMR, which is limited by molecular tumbling rates for large molecules. This makes SSNMR on UHF systems particularly advantageous for studying large biological systems such as enzymes, assemblies, and receptors, as the improved resolution enhances spectral dispersion and helps isolate signals of interest from overlapping resonance peaks [44].

FAQ 3: My sample lacks a deuterated solvent for an internal lock. How can I stabilize the magnetic field during long SSNMR experiments?

For samples that lack an internal deuterium source, an external 2H lock system is used. This involves a specialized SSNMR probe designed with an external lock coil containing a sealed capillary of D2O, positioned within the magnet's homogeneous field region alongside the sample coil. This setup allows for continuous magnetic field stabilization via the deuterium lock signal without being part of your sample, thus maintaining radio frequency probe performance and compensating for field drift that can be particularly pronounced in new gigahertz-class magnets [44].

FAQ 4: What are the common signs of magnetic field instability in my SSNMR spectra, and how does it affect data on large proteins?